Chapter 92 Pregnancy-Related Diseases

Retinal and choroidal disorders arising in pregnancy

Pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Early reports gave an impressive rate of visual disturbances. Scotoma, diplopia, dimness of vision, and photopsias were noted in 25% of patients with severe pre-eclampsia and up to 50% of patients with eclampsia.1 Recent studies, discussed below, suggest that the rate of visual disturbance has decreased markedly with improved medical management of pre-eclampsia. Although photic stimuli may predispose to seizures in susceptible patients, the benefits of an ophthalmoscopic examination outweigh the small risk of seizure when an examination is indicated.2

Pre-eclampsia and eclampsia have been associated with a retinopathy similar to hypertensive retinopathy; serous retinal detachments; yellow, opaque retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) lesions; and cortical blindness. Arterial and venous occlusive disease can also occur and may contribute to visual loss. Early studies of retinal disorders in pre-eclampsia have been discussed in previous reviews.3

Retinopathy in pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Focal or generalized retinal arteriolar narrowing is the most common ocular change seen in pre-eclampsia, but its frequency is declining. Early studies reported arteriolar attenuation in 40–100% of pre-eclamptic patients.4 A retrospective study of fluorescein angiograms in pre-eclamptic patients by Schreyer identified normal retinal vessel caliber in 16 of 16 patients. In contrast, 4 of 14 patients with pre-existing chronic systemic hypertension had retinal vascular changes.5 Jaffe prospectively demonstrated a statistically significant difference in arteriolar caliber between 56 study participants with severe pre-eclampsia and 25 healthy controls, but no difference between 17 patients with mild pre-eclampsia and controls.6 These studies suggest that arteriolar narrowing may be more common in pregnant patients with chronic pre-existing hypertension than those with mild pre-eclampsia. The difference in the reported prevalence of retinopathy between the early and recent literature is probably related to better medical management of pre-eclampsia and its complications.

The cause of retinal arteriolar narrowing seems to be central retinal artery vasospasm suggested by increased central retinal artery blood flow velocity.7 When present, the retinal arteriolar attenuation associated with pre-eclampsia generally resolves after delivery, presumably due to normalization of central retinal artery blood flow. Other typical hypertensive retinopathy changes such as hemorrhages, cotton-wool spots, lipid deposits, diffuse retinal edema, and papilledema are generally not seen in pre-eclampsia6 and should raise suspicion about additional concurrent systemic disease. Recently, Gupta and colleagues found that the severity of retinopathy in pre-eclampsia is directly related to the level of placental insufficiency and intrauterine growth retardation. Serum uric acid levels also had a statistically significant correlation with retinopathy in this group, but the meaning of this finding needs further research to investigate possible causation. Interestingly, the severity of retinopathy did not correlate with degree of systolic or diastolic hypertension, suggesting that retinopathy in pre-eclampsia may be independent of systemic blood pressure.8

Choroidopathy in pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Choroidal dysfunction is a common ocular complication of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia that manifests clinically as serous retinal detachments or yellow RPE lesions. The serous retinal detachments usually are bilateral and bullous but occasionally are cystic.2,9 In the early twentieth century, serous retinal detachments were seen in 1% of severely pre-eclamptic patients and about 10% of eclamptic patients.10,11 More recently, Saito retrospectively evaluated 31 women with severe pre-eclampsia or eclampsia and found that 40/62 (65%) eyes had serous retinal detachments and 36/62 (58%) had RPE lesions. RPE lesions were usually located in the macular or peripapillary regions, 33/36 (92%) were solitary or grouped, and 3/36 (8%) were large and geographic. After delivery, all serous retinal detachments and RPE lesions resolved. The three eyes with geographic RPE lesions all developed significant chorioretinal atrophy.12 The apparent historical increase in the incidence of serous detachments and RPE lesions is almost certainly due to improved examination instrumentation and diagnostic testing such as fluorescein angiography.

The etiology of choroidal dysfunction is thought to be ischemia based on fluorescein angiography, limited histopathologic study, the presence of Elschnig spots on resolution13 and indocyanine green angiography.14 This is further supported by the observation that posterior ciliary artery blood flow velocity is increased in pre-eclampsia suggesting vasospasm.7 The primary choriocapillaris ischemia presumably leads to RPE ischemia manifest as yellow opacification and/or fluid pump dysfunction allowing subretinal fluid accumulation.

Although serous retinal detachment and RPE dysfunction can cause marked loss of visual acuity, these changes fully resolve postpartum and most patients return to normal vision within a few weeks. Some patients have residual RPE changes in the macula. Years later, these changes can mimic a macular dystrophy or tapetoretinal degeneration.15 Rare patients may develop optic atrophy if chorioretinal atrophy is extensive.16

Saito has suggested that serous detachments are more specific to pre-eclampsia and eclampsia, whereas retinopathy is seen more often in pre-eclampsia superimposed on pre-existing hypertension.17 Retinopathy is associated with higher levels of blood pressure than is serous detachment.18 Although retinopathy was believed to be a reflection of possible placental insufficiency and possible adverse neonatal outcome, serous retinal detachment is not an additional risk factor.19

Postpartum serous detachments have been reported in pre-eclamptic patients,20,21 and there are rare reports of exudative detachments in patients without pre-eclampsia.22,23 While these serous retinal detachments may be mechanistically distinct, they also resolve over several weeks.

The HELLP syndrome consists of hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets, and it is generally associated with severe pre-eclampsia or eclampsia. Bilateral serous retinal detachments and yellow-white subretinal opacities have been seen in rare patients with this disorder.24–28

Other ocular changes seen in pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

Cortical blindness that appears late in pregnancy or shortly after delivery is an uncommon complication of severe pre-eclampsia and eclampsia. The etiology of vision loss may be occipital ischemia in watershed areas from vasospasm,29–32 possibly related to extracellular hypercalcemia,33 ischemia from antiphospholipid antibody-related vascular occlusion,34 vasogenic edema,35–42 petechial41 or larger hemorrhages,42,43 hypertensive encephalopathy,44,45 ischemia from hypotension during delivery,46 or as part of a postictal state.47 Most patients recover normal vision over several weeks. A prospective study by Cunningham showed that 15/15 women with cortical blindness experienced complete recovery over 4 hours to 8 days. CT scanning was obtained in 13/15 and MRI scanning in 5/15 revealing edema and petechial hemorrhages in the occipital cortex.41

The presence of large intracranial hemorrhages may portend a worse prognosis in terms of both mortality and visual recovery. Akan evaluated CT scans from 22 patients with neurologic complications from eclampsia and found that 2 of the 3 patients who died had massive intracranial hemorrhages.42 Drislane found that among 4 patients with severe pre-eclampsia and multifocal cerebral hemorrhages, 1 died and the 3 others developed prolonged cognitive deficits.43

Cortical vision loss has been reported in eight patients with HELLP syndrome. One had postictal cortical dysfunction,47 one had venous sinus thrombosis,48 two had signs of cortical ischemia or edema,49,50 and one was idiopathic.51 Three patients (2.7%) in a prospective evaluation of 107 women diagnosed with HELLP syndrome developed cortical blindness.52 Retinal arterial and venous occlusions have been reported in patients with pre-eclampsia. These may be a cause of irreversible visual loss and will be discussed later. Other ocular disorders reported associated with pre-eclampsia and eclampsia include ischemic optic neuropathy53 and optic neuritis,54,55 ischemic papillophlebitis,56 peripheral retinal neovascularization,57 choroidal neovascularization,58 macular edema,59 macular ischemia,60 and a tear of the retinal pigment epithelium.61 One patient with HELLP syndrome was reported to have developed a vitreous hemorrhage.62

Central serous chorioretinopathy

Central serous chorioretinopathy (CSC) is caused by localized RPE dysfunction resulting in the accumulation of subretinal fluid. People between the ages of 20 and 50 years are typically affected and there is an 8 : 1 male predominance.63 Pregnancy may predispose some women to CSC. The limited amount of information available concerning CSC in pregnancy makes it difficult to determine whether CSC during pregnancy is typical CSC coincident with pregnancy or if it is a separate disorder possibly related to the hormonal hypercoagulability or hemodynamic changes of pregnancy.

Only a few dozen cases of CSC associated with pregnancy are reported in the medical literature.64–72 Unlike the serous retinal detachments observed in pre-eclampsia and eclampsia, CSC is generally unilateral. The women were all previously healthy and no cases were associated with pre-eclampsia or eclampsia. No patients had antecedent eye disease other than refractive error. Primiparas and multiparas were both represented. Most of the cases developed in the third trimester and all resolved spontaneously within a few months after delivery. There were no cases of significant visual sequelae.

Pregnancy associated CSC may recur in the context or outside of subsequent pregnancy. CSC recurred in at least two women, always in the same eye, in subsequent pregnancies. One patient had four successive pregnancies with CSC,70 and one had two successive pregnancies complicated by CSC.71 There is also one case report of a woman developing CSC 1 month postpartum in two successive pregnancies.72 However, there is also a report of a woman with CSC in her third pregnancy who did not experience a recurrence during a subsequent pregnancy.67 So the occurrence of CSC during one pregnancy does not necessarily mean that it will recur with future pregnancies. There is a report of one patient who experienced a recurrence of CSC outside the context of pregnancy.67

There is an increased incidence of subretinal white exudates (presumed to be fibrin) in pregnancy-associated CSC (approximately 90%) compared to CSC in males and nonpregnant women (approximately 10%). Sunness reported that 3 of 4 patients with pregnancy-related CSC had subretinal exudates.67 Gass found that 6/6 cases of pregnancy related CSC had subretinal exudates compared to only 6/50 (12%) of non-pregnancy related cases.68 However, a recent series of 3 pregnant women with CSC without any exudates has been reported.73 The cause of this higher prevalence of subretinal exudates in pregnant women is unknown.

Occlusive vascular disorders

An increase in the level of clotting factors and clotting activity occurs during pregnancy.74 Several pathologic sources of thrombosis and embolic events can also occur. One review of ischemic cerebrovascular disease suggested that pregnancy is associated with a 13-fold increase in the risk of cerebral infarctions compared to nonpregnant women.75 This increased risk of vaso-occlusive disease may also manifest as retinal or choroidal vascular occlusions.

Retinal artery occlusion

Two cases of unilateral central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO),76,77 one case of bilateral CRAO,78 five cases of unilateral branch retinal artery occlusion (BRAO),79,80 and 3 cases of bilateral multiple BRAO75 have been reported in association with pregnancy and in the absence of additional risk factors. One case of cilioretinal artery occlusion has been reported.81 Three cases of arteriolar occlusion were associated with pre-eclampsia78,82 and 1 was associated with disc edema.80 Five of the 12 (42%) cases occurred within 24 hours of delivery, suggesting that this is a particularly susceptible period. Two of the patients with unilateral BRAO also were found to have mild transient protein S deficiency upon further systemic workup.83

Blodi reported that multiple retinal arteriolar occlusions were seen within 24 hours after childbirth in four women. Two patients were pre-eclamptic and required cesarean section. One of the two also had evidence of cerebral infarctions. The third patient had hypertension, pancreatitis, and premature labor. The fourth was a previously healthy 16-year-old who had an oxytocin-induced labor and had a generalized seizure 2 hours after delivery. The patients reported decreased vision and all had fundus findings characterized by retinal patches characteristic of ischemia and intraretinal hemorrhages that were similar to Purtscher’s retinopathy. After resolution, patients were left with focal arteriolar narrowing and optic disc pallor. The visual acuities ranged from 20/20 to 4/200 and visual field defects were compatible with the areas of occlusion. The authors suggest that complement-induced leukoemboli could have caused the retinal arteriolar occlusions.82

At least eight additional cases of pregnancy-associated BRAO have been reported in the literature.84–90 However, all of these cases had significant additional risk factors for vascular occlusion. Since pregnancy is a common condition, it is difficult to know whether these cases represent true pregnancy associations, multifactorial or synergistic etiologies, or just chance occurrences. One case was associated with intramuscular progestogen therapy for a threatened abortion.84 Three cases that occurred postpartum were associated with hypercoagulability from protein C85 or protein S82,86 deficiency. Two cases were associated with thromboembolic occlusions attributed to mitral valve prolapse87 and amniotic fluid embolism.88 The final 2 cases developed BRAO in the first trimester in association with migraine headaches.89

Retinal vein occlusion

Retinal vein occlusion associated with pregnancy is exceedingly rare. Only 5 pregnancy-related central retinal vein occlusions (CRVO) have been reported to date91–93 and we are not aware of any branch retinal vein occlusions. A study of central retinal vein occlusions with diurnal intraocular pressure determination in young adults included a 33-year-old pregnant woman in her third trimester who had unilateral venous dilation and tortuosity with two subretinal hemorrhages and mild foveal edema.91 Gabsi reported the case of a 27-year-old who was 6 months pregnant when she developed a unilateral CRVO. The authors suggested impaired fibrinolysis after venous stasis as a possible mechanism.92 A 30-year-old woman presented in the 28th week of her second pregnancy with HELLP syndrome. She developed a unilateral CRVO 10 days after emergency caesarean section.93 Rahman reported a case of CRVO associated with pre-eclampsia 3 weeks postpartum in a 20-year-old woman.94 The final case is that of a mild bilateral CRVO that developed early in pregnancy and resolved over several months (J. Wroblewski, personal communication). The paucity of reported cases linking pregnancy to retinal vein occlusion makes the strength of this association suspect.

Disseminated intravascular coagulopathy

Disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC) is an acute pathological process with widespread thrombus formation in small vessels. It can occur in obstetrical complications such as abruptio placentae and intrauterine fetal death that release placental thromboplastin into the maternal circulation and activate the extrinsic coagulation system. This process has a tendency to occlude the posterior choroidal vessels leading to RPE ischemia, dysfunction of the retinal pigment epithelial pump mechanism, and subsequent serous retinal detachments in the macular and peripapillary regions.95–98 The development of serous retinal detachments in pregnancy, especially late pregnancy, may be an early ocular sign of DIC.98 We are aware of case reports of only 2 patients in whom DIC caused serous retinal detachments.95,98 These detachments tend to be bilateral and symptomatic. With recovery from the systemic disorder, vision generally returns to normal with only residual pigmentary change.97,98 Patel reported a case of bilateral retinochoroidal infarction associated with pre-eclampsia and DIC with permanent vision loss.99

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) is a rare, idiopathic, acute, systemic coagulopathy characterized by platelet consumption and thrombus formation in small vessels. TTP occurs at any age with a peak incidence in the third decade of life and a female to male preponderance of 3 : 2. Visual changes occur in approximately 8% of cases100 due to thrombus formation in the choriocapillaris and secondary RPE ischemia. Clinical findings are usually bilateral and include serous retinal detachments, yellow spots at the level of the RPE, and localized arteriolar narrowing. We are aware of 32 reported cases of TTP in association with pregnancy. Sequelae include RPE pigmentary changes and Elschnig spots with a return to baseline vision over several weeks in most cases.100–102

Amniotic fluid embolism

Amniotic fluid embolism is a serious complication of pregnancy with high mortality, second only to pulmonary thromboembolism as a cause of death during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Those patients who survive the initial event usually develop DIC103 with the potential ocular complications described above. Two patients developed multiple branch retinal arteriolar occlusions, presumably related to particulate material from the amniotic fluid.104,105 Another patient had massive blood loss from an amniotic fluid embolism leading to severe retinal and choroidal ischemia and blindness in one eye.106

Uveal melanoma

Pregnancy is heralded by a hormone-dependent tendency to hyperpigmentation and well-known cutaneous changes like chloasma and an increase in pigmentation of pre-existing nevi owing to increased levels of melanocyte-stimulating hormone in pregnancy.107 Although estrogen and progesterone may stimulate melanogenesis, there is no evidence that this can cause malignant transformation of melanocytic cells.

A case–control study by Holly et al. found a decreased risk of uveal melanoma for women who had ever been pregnant with an increase in protective effect with more live births. The largest effect was observed between nulliparous and parous women.108 Others, however, have reported a trend toward a larger-than-expected number of ocular melanomas presenting during pregnancy.109 There are also a number of anecdotal reports of uveal melanomas presenting or growing rapidly during pregnancy.110–115 These reports led to speculation that uveal melanoma may be hormone-responsive but two studies have failed to show any estrogen or progesterone receptor expression in ocular melanomas.113,116 A large retrospective study showed no association of uveal melanoma with the use of oral contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy.117 It is possible that other hormones may be involved113 or that tumor growth may be related to pregnancy-associated immune modulation.

Pregnancy-related uveal melanoma does not seem to differ histologically from uveal melanoma not associated with pregnancy. Shields reported that among 10 pregnancy-related choroidal melanomas evaluated after enucleation the tumors did not differ in cell type, mitotic activity, and other features when compared to a matched group of tumors in nonpregnant women.118

The treatment of pregnancy-associated uveal melanoma has been described in two studies. Among 16 cases reported by Shields, 10 eyes were enucleated, 4 received plaque radiotherapy during or after pregnancy, and 2 cases were observed. Among 14 of 16 patients who elected to carry the pregnancy to term, all delivered healthy babies with no infant or placental metastases.118 Romanowska-Dixon reported 8 cases in which there were no treatment-related pregnancy complications. The authors do suggest that brachytherapy is safer towards the end of pregnancy or after delivery.119

Childbearing may be associated with improved survival in choroidal melanoma. Egan et al. performed a large prospective cohort study in which death rates from metastasis were 25% higher in nulliparous women and men than in women who had given birth. The protective influence of parity was greatest in the first 3 years of follow-up and increased with the number of live births.120 These results contradict a small earlier study by the same group that concluded rates of metastasis were not higher among women who reported pregnancies or oral contraceptive use.121 A much smaller study by Shields also showed similar 5-year survival between pregnant and non-pregnant women with posterior uveal melanoma.118

Other changes arising in pregnancy

A choroidal osteoma has been reported that presented in the ninth month of pregnancy with visual loss due to choroidal neovascularization.122 Cases of acute macular neuroretinopathy,123,124 Valsalva maculopathy,125 and cystoid macular edema126 have been observed in the immediate postpartum period. Placental metastases from orbital rhabdomyosarcoma127 and primary ocular melanoma have been reported.128

Pre-existing conditions

Diabetic retinopathy

The modern medical, ophthalmologic, and obstetrical management of pregnant diabetic patients has greatly improved the outcome of pregnancy for both the fetus and the mother. Laser photocoagulation has reduced the risk of vision loss from diabetic retinopathy and improved glucose control has improved the likelihood of good fetal outcomes. Well-controlled blood glucose and adequate glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) before conception and throughout the pregnancy may reduce the risk of spontaneous abortion,129,130 congenital anomalies, and fetal morbidity.131 A recent study suggested that the severity of diabetic retinopathy may be a significant factor in predicting adverse fetal outcomes, even after correcting for blood glucose control.132 Another study suggested, however, that blood glucose control may counteract adverse fetal effects associated with maternal retinopathy and nephropathy.133

Diabetic women who may become pregnant should establish excellent glucose control before conception, since the major period of fetal organogenesis may take place before the mother is even aware that she is pregnant. In addition, a diabetic woman’s retinopathy status should be evaluated and stabilized prior to conception. This is particularly important for patients with severe nonproliferative or proliferative retinopathy because scatter laser photocoagulation may reduce progression during pregnancy.134 Laser treatment of diabetic macular edema before pregnancy may also be important, although the effects of pregnancy on macula edema have not been adequately studied.

The Diabetes in Early Pregnancy Study (DIEP), a study of 155 insulin-dependent diabetic pregnancies,135 as well as the data from the Diabetic Control and Complications Trial136 and the previous data summarized by Sunness,134 all provide evidence that better metabolic control before pregnancy diminishes the progression of diabetic retinopathy. Recent studies have found a strong correlation between the glycosylated hemoglobin level in the first month and the degree of deterioration once tight metabolic control is achieved.135 Nerve fiber layer infarctions commonly are associated with the institution of tight metabolic control of chronic hyperglycemic patients. One study described the retinopathy status of 13 patients managed by insulin pump during pregnancy. Two patients who had rapid decrease in the HbA1c level developed acute ischemic changes and ultimately proliferative retinopathy.136 However, the long-term benefits of adequate blood glucose control outweigh concerns about the transient worsening of retinopathy that has been associated with the sudden imposition of tight metabolic control.137–139

The frequency of ophthalmic follow-up of a diabetic patient during pregnancy is determined by her baseline retinopathy status. Guidelines for eye care in diabetic patients recommend that a diabetic woman planning pregnancy within 12 months should be under the care of an ophthalmologist, undergo repeat evaluation in the first trimester, and after that at intervals dependent on the initial findings.132,140

Progression of diabetic retinopathy during pregnancy

Retinal hemodynamics may play an important role. The increase in cardiac output combined with decreased peripheral vascular resistance during pregnancy141 have been suggested as pathogenic factors for the development or progression of diabetic retinopathy. Three studies suggest that retinal hyperperfusion may exacerbate pre-existing microvascular damage.142–144 In contrast, two studies report a reduction in retinal capillary blood flow that may exacerbate ischemia and lead to retinopathy progression.145,146 Other studies have suggested a possible role for various growth factors found at increased concentrations during pregnancy such as IGF-1,147 phosphorylated IGF-binding protein,148 placenta growth factor,149,150 endothelin-1,151 and fibroblast growth factor-2.152 These factors may exert additive or synergistic effects.153

Short- and long-term effects of pregnancy on diabetic retinopathy

Since there is a high rate of regression of retinopathy during the postpartum period, one must consider short-term and long-term changes separately. The DCCT research group reported that pregnant women in the conventional treatment group were 2.9 times more likely to progress three or more levels from baseline retinopathy status than nonpregnant women. The odds ratio peaked during the second trimester and persisted as long as 12 months after delivery.154 One study of short-term effects included 16 women with no retinopathy or nonproliferative retinopathy. Progression during pregnancy was compared to progression between 6 and 15 months postpartum in the same women. The number of microaneurysms showed a rapid increase between the 28th and 35th weeks of pregnancy. Six months postpartum the number of microaneurysms decreased but in most cases remained higher than the baseline level. The number of microaneurysms remained stable over the subsequent 9-month postpartum period.155

Three other studies compared short-term progression of retinopathy between separate control groups of nonpregnant women and pregnant women over the same time period. The first compared the course of diabetic retinopathy in 93 pregnant women and 98 nonpregnant women. Progression was observed in 16% of the pregnant group compared to only 6% in the nonpregnant patients. Furthermore, 32% of the nonpregnant group had retinopathy at baseline compared to only 22% of the pregnant cohort. Therefore, one might have expected more progression in the nonpregnant group due to worse baseline disease, making these findings more significant.156 A second study compared 39 nonpregnant women, 46% of whom had retinopathy at baseline, with 53 pregnant diabetic women, 57% of whom had retinopathy at baseline. In the nonpregnant group the microaneurysms remained stable, streak or blob hemorrhages appeared in three patients (8%), and no nerve fiber layer infarctions developed over 15 months. In the pregnant group, microaneurysms increased moderately, and streak and blob hemorrhages and nerve fiber layer infarctions increased markedly over the same follow-up period. One patient with nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy from the pregnant group developed proliferative retinopathy.157 In the third study, there were 133 pregnant and 241 nonpregnant women. The groups were statistically equivalent in terms of baseline retinopathy levels. Within each quartile of glycosylated hemoglobin, pregnant women had a greater tendency to have worsening of retinopathy and the nonpregnant women had a greater tendency to have improvement in their level of diabetic retinopathy during the follow-up interval.158

There are four studies concerning the long-term effects of pregnancy on diabetic retinopathy. The first included 40 women followed for 12 months postpartum. Among 19 study participants with no retinopathy at baseline, 30% developed mild nonproliferative retinopathy during the second and third trimester. By one year postpartum none had clinically detectable retinopathy. Among the 21 women with retinopathy at baseline, 11 worsened during pregnancy and 2 developed proliferative disease. None of these 11 women had regressed to her initial retinopathy status by 1 year postpartum.159 The second study reported changes at 12 months postpartum. Among 10 patients with no initial retinopathy who developed mild retinopathy during pregnancy, half experienced total postpartum regression, 30% had partial regression, and 20% had no change. Among 5 patients with initial mild retinopathy who progressed to moderate nonproliferative retinopathy, 40% experienced complete regression, 40% partial regression, and 20% no regression. However, among 12 who progressed from mild initial retinopathy to severe nonproliferative retinopathy, only 17% had total regression, 58% had partial regression, and 25% had no regression. The third study compared 28 diabetic women to 17 nulliparous matched controls over a 7-year period. Only 5 of 26 (19.2%) women who had been pregnant experienced progression of retinopathy compared to 8 of 16 (50%) nulliparous women, suggesting that pregnancy does not affect long-term progression and may even afford a protective effect.160 A final study of 80 women who had completed at least 1 successful pregnancy found no increase in the risk of proliferative retinopathy later in life compared to matched controls.161

Two studies suggest that the number of prior pregnancies does not appear to be a long-term factor in the severity of retinopathy present when duration of diabetes is taken into account.162,163 In fact, a cross-sectional European study reported lower levels of retinopathy in diabetics with multiple pregnancies compared with women matched for age and duration of diabetes.164 It is not clear if this improved status was caused by a prolonged period of tight metabolic control and better patient education, or if pregnancy confers a long-term protective effect. Another possibility involves the bias that only women with better metabolic control may have undergone the stress of multiple pregnancies.

The role of baseline retinopathy status, duration of diabetes, and metabolic control

The major determinants of the progression of diabetic retinopathy in a pregnant woman are the duration of diabetes and the degree of retinopathy at the onset of pregnancy.134,135,157,165–167 Therefore, women with diabetes are strongly encouraged to complete childbearing early in their adult life.168

The baseline level of retinopathy at conception is the major risk factor for progression of retinopathy, according to the DIEP. When a logistic regression model was used to separate the influence of diabetes duration (shorter duration being less than 15 years, longer duration being more than 15 years) from the effect of a worse baseline level of nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy, the baseline retinopathy was highly significant but the duration of retinopathy was not. Analysis of patients with moderate or more severe retinopathy in the DIEP showed deterioration (defined as a two-step or more worsening determined on the final scale of the modified Airlie House Diabetic Retinopathy Classification) in 55% of patients with shorter duration and 50% of patients with longer duration of diabetes. However, the rates of development of proliferative retinopathy were 39% of patients with longer duration of diabetes and only 18% of patients with shorter duration of diabetes. The HbA1c level at the beginning of pregnancy was used in the DIEP as a measure of metabolic control. Women with a HbA1c level of 6 standard deviations (SD) or more from the control mean had a statistically significant higher risk of progression of retinopathy compared with patients with a HbA1c baseline level within 2 SD of the control mean.135

A longitudinal analysis of the effect of pregnancy on microvascular complications in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) was recently published. Pregnant women in the intensive treatment group had a 1.63-fold greater risk of retinopathy progression during pregnancy than nonpregnant women, compared to a 2.48-fold greater risk in the conventional treatment group.154

A prospective study of 179 pregnancies in 139 women with type-1 diabetes reported a 10% progression rate of retinopathy in women with a duration of diabetes of 10–19 years compared to 0% in women with duration less than 10 years. Furthermore, women with moderate to severe retinopathy experienced progression in 30% of cases compared to only 3.7% with less severe retinopathy.169

Lauszus prospectively followed 112 pregnant women with insulin-dependent diabetes and found an association between the severity of retinopathy and poor glycemic control before and after pregnancy. However, no such correlation was found with intensive glycemic control during pregnancy. Those women who had progression of retinopathy during or after pregnancy had an average diabetes onset at age 14 years compared to 19 years in women whose retinopathy remained stable.170

The following discussion of the progression of retinopathy during pregnancy is subdivided according to the baseline level of retinopathy present. Many of the studies did not use the more recent classification recommended by the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS). Whenever possible, the results have been organized according to this classification.171

No initial retinopathy

Sunness summarized nine studies that included 484 diabetic pregnancies with no initial retinopathy. Twelve percent of these patients developed some background change during pregnancy, and one patient (0.2%) developed proliferative retinopathy. In 23 cases with progression for which postpartum follow-up was available, there was some regression of the nonproliferative changes in 57%.134 The DIEP reported a 10.3% progression to mild nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy for this group of patients.135 Four other studies of eyes with no initial retinopathy reported progression rates of 0%, 7%, 26%, and 28% respectively.167,172–174

A 12-year prospective study of patients with gestational diabetes did not demonstrate an increased risk of diabetic retinopathy.175 Retinal vascular tortuosity in gestational diabetics has been reported, however, and some degree of tortuosity persisted at 5 months postpartum.176 There is one case report of a previously healthy nulliparous woman with gestational diabetes diagnosed at 8 weeks’ gestation. Glycemic control was instituted and the patient developed bilateral proliferative retinopathy by 31 weeks’ gestation. The patient had a markedly elevated HbA1c at initial diagnosis suggesting that she may have been diabetic before becoming pregnant.177 Puza reported a retrospective review of 100 gestational diabetics and concluded that routine examinations have little utility in these patients.178

Mild nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy

In two studies that included 24 pregnant women with fewer than 10 microaneurysms and dot hemorrhages in both eyes, 8% developed additional microaneurysms and 0% developed proliferative retinopathy.134 A more recent study showed that microaneurysm counts increase during pregnancy, peak at 3 months postpartum, and then decline to baseline levels.179 The DIEP study found that 18.8% of patients with mild nonproliferative retinopathy showed a 2-step progression on the modified Airlie House classification through the end of pregnancy. Only 6% progressed from mild nonproliferative to proliferative retinopathy.135 A study that included 7 patients with minimal retinopathy reported progression in only 1 during pregnancy that improved after delivery.174

Moderate to severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy

The DIEP found that 54.8% of patients with moderate retinopathy showed a two-step progression on the modified Airlie House diabetic retinopathy classification and 29% developed proliferative retinopathy by the end of pregnancy.135 In addition, 25% of those who developed proliferative retinopathy had high-risk characteristics as defined by the Diabetic Retinopathy Study.180

The results of 10 studies published before 1988 that included 259 pregnant women with nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy were summarized by Sunness. The analysis of this information showed that 47% of patients had an increase in the severity of nonproliferative changes during pregnancy. Differences in the scale of measurements of diabetic retinopathy among the studies caused wide variations in progression rates. Most of the studies included mild and moderate retinopathy in the wider group of nonproliferative retinopathy. Only 5% of patients in this analysis developed proliferative retinopathy during pregnancy.134

Four studies after 1988 reported progression rates of nonproliferative retinopathy ranging from 12% to 55%.167,172,173,181 Two of these studies reported rates of proliferative retinopathy development at 8% and 22% during pregnancy.173,181

Proliferative retinopathy

Sunness summarized 12 studies, including 122 women with proliferative retinopathy at baseline. Of these 122 women, 46% had some increase in neovascularization that occurred during pregnancy.134 A more recent study reported a 63% rate of progression in eyes with proliferative retinopathy at baseline.167

Optimal treatment of proliferative disease before pregnancy reduces the risk of progression during pregnancy. In the 1988 Sunness review, those patients who had scatter laser photocoagulation before pregnancy showed a 26% rate of progression of their proliferative disease and visual loss compared to 58% of patients without prior treatment. Those patients with complete regression of proliferative disease before pregnancy did not demonstrate progression of proliferative disease during pregnancy.134 Somewhat different results were found in a later study by Reece. In this analysis, half of the patients with proliferative disease who underwent scatter laser photocoagulation prior to pregnancy required additional scatter treatment during pregnancy. In addition, 65% of patients who had proliferative disease during pregnancy required photocoagulation postpartum. No patient had proliferative disease that did not respond to laser photocoagulation.182

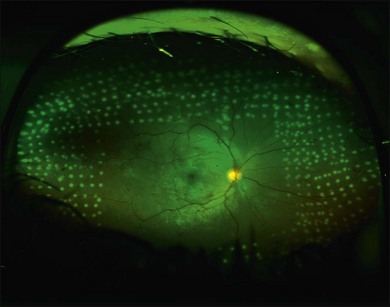

Proliferative retinopathy may regress near the end of pregnancy or in the postpartum period. One study found that four out of five women who developed proliferative retinopathy during pregnancy had spontaneous regression to nonproliferative status within 2 months postpartum.159 In contrast, another study of 8 women with proliferative disease reported no spontaneous regression by 3 months postpartum.167 The possibility of spontaneous regression is a factor to consider when determining if laser photocoagulation is indicated. Most retina specialists would aggressively treat patients who have high-risk proliferative retinopathy; some retinal specialists would treat one eye or both in cases that are not high risk, given the problem of rapid progression during pregnancy. Figure 92.1 shows the right eye of a 29-year-old diabetic woman who was 25 weeks pregnant at the time of her initial presentation. Figure 92.2 shows the same patient 3 months later. After consideration of high-risk factors such as high initial HbA1c and duration of diabetes, these decisions must be made on a case-by-case basis.

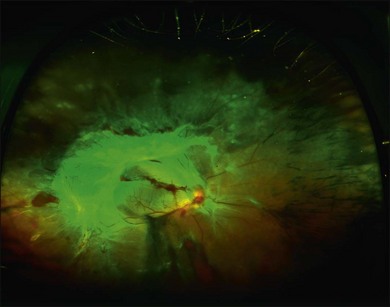

Fig. 92.2 Wide-angle fundus photo of the same patient as Fig. 92.1 showing the right eye 3 months later. She had received additional scatter laser at 29 weeks’ gestation, and at 33 weeks’ gestation her neovascular tissue appeared to be regressing and no further laser was added. She delivered her baby at 35 weeks’ gestation. She presented 3 weeks postpartum with vision loss in the right eye and had progressed to severe traction retinal detachment involving the entire retina despite having had complete laser treatment. Laser scars can be seen on detached retina in the nasal periphery.

Vitreous hemorrhage during labor and delivery has been reported in a few cases.183 Currently, no evidence justifies performing a cesarean section on the basis of proliferative retinopathy alone, given the availability of vitrectomy for the treatment of nonclearing vitreous hemorrhage.134

Diabetic macular edema in pregnancy

Diabetic macular edema that involves or threatens the fovea is currently treated with anti-VEGF injections, with or without focal laser photocoagulation outside the context of pregnancy in order to reduce the risk of moderate vision loss. Patients who develop macular edema during pregnancy frequently have different prognoses than nonpregnant patients. Spontaneous resolution after pregnancy is a common occurrence and is associated with improvement of visual acuity more frequently than in nonpregnant patients.181

Sinclair and Nessler reported that 16 (29%) of 56 eyes of diabetic pregnant women with initial proliferative or nonproliferative retinopathy developed diabetic macular edema during pregnancy. Of these 16 eyes, 14 (88%) had improvement in visual acuity and resolution of macular edema postpartum without laser treatment.184

Other risk factors for progression of diabetic retinopathy during pregnancy

Nephropathy and systemic hypertension are additional risk factors for the progression of diabetic retinopathy during pregnancy. A well-known association exists between nephropathy and retinopathy in nonpregnant patients. One study in pregnant diabetics showed that 8 of 9 patients in whom macular edema developed during pregnancy had proteinuria of more than 1 g per day.185 Two studies report elevated systolic blood pressure as a risk factor for the progression of diabetic retinopathy.167,186 Systolic blood pressure within the normal range but over 115 mmHg has been associated with an increased risk of retinopathy progression among pregnant patients.172 The DIEP found a 1.3 odds ratio for two-step progression of retinopathy for every 10 mmHg increase in systolic blood pressure.135

Diabetic retinopathy and maternal and fetal wellbeing

Advanced diabetic retinopathy has been considered a risk factor for adverse fetal outcomes because it may reflect more widespread systemic disease. Pregnancies associated with nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy may not be at higher risk for adverse fetal outcomes.187 However, Klein reported an adverse fetal outcome in 43% of 28 women with proliferative retinopathy compared to only 13% of 131 women with nonproliferative retinopathy.132 Another study of 20 pregnancies of 17 women with proliferative retinopathy reported spontaneous abortion in 2 cases (10%), stillbirth in 1 case (5%), and 3 had major congenital anomalies.182 Sameshima reported that among 60 pregnant patients with diabetes, the 7 with proliferative retinopathy had a significantly higher incidence of fetal distress.188 A final study of 26 women with proliferative retinopathy reported serious neonatal morbidity in 19% and mortality in 12%.189

One prospective study of 205 women with type-1 diabetes found that low birth weight was associated with retinopathy progression. However, retinopathy progression was not associated with earlier delivery, macrosomia, respiratory distress syndrome, neonatal hypoglycemia, or neonatal death.190

Improved medical and obstetrical management has improved the outcome of diabetic pregnancies. In a study of 22 pregnancies complicated by retinopathy and nephropathy in which good glycemic control was present antepartum and throughout pregnancy, there were no infant deaths and only 1 case of mild respiratory distress syndrome.133 A retrospective study of 482 diabetic pregnancies reported only 3 perinatal deaths, which was statistically equivalent to nonpregnant deliveries over the same period.191

Two studies suggest an association between diabetic retinopathy and the development of pre-eclampsia. Hiilesmaa followed 683 consecutive pregnancies with type-1 diabetes and found that retinopathy was a statistically significant independent predictor of pre-eclampsia.192 A second study looked retrospectively at 65 pregnant type-1 diabetic patients and reported that deterioration of retinopathy occurred more frequently in those with pre-eclampsia (4/8) than those without pre-eclampsia (5/65).193 Perhaps central retinal artery vasospasm associated with pre-eclampsia exacerbates retinal ischemia.

Toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis

The likelihood of congenital toxoplasmosis occurring in the offspring of a mother with active retinochoroiditis or chorioretinal scars is often a concern. This usually is unfounded, however, since congenital toxoplasmosis in the fetus results only from infection of the mother that occurs during the pregnancy itself. The presence of focal toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis or scars in a patient reflects congenital infection of that patient in essentially all cases and not new infection of the mother.194

Therefore the fetus of a woman with active retinochoroiditis or scars should not be at risk for contracting congenital toxoplasmosis. A study of 18 pregnant patients with active toxoplasmosis or scars, some with high stable toxoplasmosis titer, found that no infants developed congenital toxoplasmosis.195

A recent retrospective study reported the ocular characteristics of active ocular toxoplasmosis during pregnancy in 9 female patients and compared these attacks with those in the nonpregnant periods. The 9 patients had 10 attacks during pregnancy and 24 attacks while not pregnant. One woman had recurrences during several pregnancies, and in total, 3 female patients had attacks only when pregnant. In general, the severity of the attacks during the pregnant and nonpregnant periods did not differ. They concluded that attacks during pregnancy were not distinctively different in severity, duration, or outcome from the attacks outside pregnancy within their cohort.196

Noninfectious uveitis

Uveitis disease activity may be altered during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Rabiah retrospectively evaluated 76 pregnancies of 50 women with noninfectious uveitis. The pregnancies were associated with Vogt–Koyanagi–Harada (VKH) syndrome in 33 women, Behçet disease in 19, and idiopathic uveitis in 24. A worsening of uveitis occurred within the first 4 months of pregnancy in 49/76 (64%) pregnancies and later in pregnancy in 17 (22%). No flare-up occurred in 21 cases (28%). An early pregnancy worsening was typical of VKH and idiopathic uveitis. Postpartum worsening occurred in 38/59 cases (64%) and was characteristic of Behçet disease.197

Six patients with preexisting VKH syndrome who improved during pregnancy have been reported.198–200 All patients had flare-ups of their disease postpartum. Sarcoid uveitis may also improve during pregnancy200 or develop de novo during the postpartum period.201 Some authors speculate that elevated endogenous free cortisol levels associated with pregnancy may suppress uveitis.201,202 However, 2 cases of VKH syndrome arising de novo in the second half of otherwise normal pregnancies have also been reported, with full remission occurring postpartum.203 The authors have diagnosed two cases of AMPPE during pregnancy, neither of which had atypical features or course of disease. Finally, Rao reported a case of a 28-year-old woman with bilateral macular choroidal neovascularization associated with punctate inner choroidopathy whose pattern of reactivation appeared to follow miscarriage of pregnancy on at least two occasions.204

Other retinal disorders

The stress of labor and delivery does not appear to pose a risk for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment in high myopes. This conclusion is based on three studies. The first examined 50 women with high myopia late in pregnancy and again in the first 2 weeks postpartum and reported no postpartum changes.205 A study of 10 asymptomatic women during 19 pregnancies who gave a history of high myopia, retinal detachment, or retinal holes or lattice degeneration did not develop any new retinal pathology after delivery.206 The final study examined 42 high myopes and 4 high myopes with previous retinal detachments before and after delivery and documented no progressive retinal changes.207

Rapid growth of choroidal hemangiomas has been reported during pregnancy.208 Another case report described the development of exudative retinal detachments associated with choroidal hemangiomas during pregnancy.209 The hemangioma may regress postpartum.210 These changes have been attributed to pregnancy-related hormonal perturbations.

Two previously healthy women developed unilateral endogenous candida endophthalmitis after undergoing surgically induced abortions. One eye underwent vitrectomy and intravitreal amphotericin B injection with a final visual acuity of 20/200. The other eye had a retinal detachment after delayed diagnosis resulting in counting fingers visual acuity.211

Retinitis pigmentosa is sometimes characterized by a sudden pregnancy-associated deterioration in visual fields after a period of relative stability. It is difficult to determine whether changes are related to pregnancy or are just coincidental. Five to ten percent of women with retinitis pigmentosa who have been pregnant reported worsening during pregnancy212,213 and did not return to baseline after delivery.212 There is one report in the literature of visual field deterioration during pregnancy, which resolved postpartum.55 One case of pericentral retinal degeneration that worsened during pregnancy has also been reported.214

Diagnostic testing and therapy

Fluorescein crosses the placenta and enters the fetal circulation in humans.215 No reports of teratogenic effects in humans have been reported to the National Registry of Drug-Induced Ocular Side Effects.134 European investigators have performed research studies involving the administration of fluorescein to 22 pregnant diabetic women and noticed no adverse effects on the fetus.216 Another study of neonatal outcome of 105 patients who underwent fluorescein angiography (FA) during pregnancy showed no increased rate of adverse neonatal outcomes.217 This study, however, included only 41 cases of FA during the first trimester, the time when teratogenic effects are more likely to take place and are more severe. Nevertheless, one survey reported that 77% of retinal specialists never perform FA on a patient they know is pregnant.218 In another survey, 89% of retina specialists who had seen a pregnant woman who required FA withheld testing out of fear of teratogenicity or lawsuit.219 We recommend that FA in pregnant women can be considered if the results would change the management of a vision-threatening problem and appropriate informed consent is obtained.

Indocyanine green does not cross the placenta, is highly bonded to plasma proteins, and is metabolized by the liver. Reports of only 6 cases of the use of indocyanine green angiography (ICGA) during pregnancy have been published.220,221 In a survey of 520 retina specialists, 105 had withheld ICGA out of fear of teratogenicity or lawsuit during pregnancy and only 24% thought it was safe to use ICGA in a pregnant patient. The authors suggest that current practice patterns concerning the use of ICGA in pregnancy may be unnecessarily restrictive.219 Like FA, we recommend that ICGA in pregnant women can be considered if the results would change the management of a vision-threatening problem and appropriate informed consent is obtained.

Photodynamic therapy

Pregnant rats exposed to verteporfin at 40 times the human dose (per kg body weight) have a high incidence of microphthalmia.222 Accidental exposure to verteporfin for photodynamic therapy during pregnancy has been reported in three cases. Rosen treated a woman with punctate inner choroidopathy with verteporfin and bevacizumab while she was 1–2 weeks pregnant, before the patient knew of her conception. The pregnancy and childbirth were uncomplicated and yielded a healthy term infant who had no abnormality for at least the first 3 months of life.223 De Santis reported a similar accidental exposure in the third week of pregnancy without any deleterious effects in the patient or child up to 26 months of life.224 Rodrigues reported a case of accidental exposure to verteporfin in a 45-year-old woman with a 25-week fetus. The pregnancy appeared to be unaffected and the child was healthy, at least through her 16-month follow-up.225 With regard to PDT during pregnancy, caution is recommended.

Anti-VEGF therapy

Anti-VEGF medications have not been well tested during pregnancy, and at least one report exists describing loss of pregnancy after intravitreal bevacizumab injection.226 However, an observational case series of four patients treated with bevacizumab in pregnancy for choroidal neovascularization secondary to choroiditis showed different outcomes. Patients received a range of 1–6 injections (mean of 2.6) while pregnant. One patient was treated with five additional injections while breastfeeding. The mean follow-up after the most recent injection was 14 months (range 11–18 months). Visual acuity improved in all patients with a mean of 5.75 lines (range 3–8 lines). All patients delivered healthy full-term infants and had an uneventful prenatal course. All children have remained healthy, exhibiting normal development and growth during infancy.227 Additional studies with more patients and longer follow-up duration are required to identify any risks associated with anti-VEGF drugs, and until such data become available, caution should be exercised.

1 Dieckmann WJ. The toxemias of pregnancy, 2nd ed. St Louis: Mosby; 1952.

2 Folk JC, Weingeist TA. Fundus changes in toxemia. Ophthalmology. 1981;88:1173–1174.

3 Sunness JS, Gass JDM, Singerman U, et al. Retinal and choroidal changes in pregnancy. In: Singerman U, Jampol LM. Retinal and choroidal manifestations of systemic disease. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1991.

4 Wagener HP. Arterioles of the retina in toxemia of pregnancy. JAMA. 1933;101:1380–1384.

5 Schreyer P, Tzadok J, Sherman DJ, et al. Fluorescein angiography in hypertensive pregnancies. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 1991;34:127–132.

6 Jaffe G, Schatz H. Ocular manifestations of preeclampsia. Am J Ophthalmol. 1987;103:309–315.

7 Belfort MA. The effect of magnesium sulphate on blood flow velocity in the maternal retina in mild preeclampsia: a preliminary color flow Doppler study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;99:641–645.

8 Gupta A, Kaliaperumal S, Setia S, et al. Retinopathy in preeclampsia: association with birth weight and uric acid level. Retina. 2008;28:1104–1110.

9 Gitter HA, Heuser BP, Sarin LK, et al. Toxemia of pregnancy: an angiographic interpretation of fundus changes. Arch Ophthalmol. 1968;80:449–454.

10 Fry WE. Extensive bilateral retinal detachment in eclampsia with complete reattachment. Arch Ophthalmol. 1929;1:609–614.

11 Hallum AV. Eye changes in hypertensive toxemia of pregnancy. JAMA. 1936;106:1649–1651.

12 Saito Y, Tano Y. Retinal pigment epithelial lesions associated with choroidal ischemia in preeclampsia. Retina. 1999;19:262–263.

13 Oliver M, Uchenik D. Bilateral exudative retinal detachment in eclampsia without hypertensive retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1980;90:792–796.

14 Valluri S, Adelberg DA, Curtis RS, et al. Diagnostic indocyanine green in preeclampsia. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;122:672–677.

15 Gass JDM, Pautler SE. Toxemia of pregnancy: pigment epitheliopathy masquerading as a heredomacular dystrophy. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1985;83:114–130.

16 Fry WE. Extensive bilateral retinal detachment in eclampsia with complete reattachment. Arch Ophthalmol. 1929;1:609–614.

17 Saito Y, Omoto T, Kidoguchi K, et al. The relationship between ophthalmoscopic changes and classification of toxemia in toxemia of pregnancy. Acta Soc Ophthalmol Jpn. 1990;94:870–874.

18 Sadowsky A, Serr DM, Landau J. Retinal changes and fetal prognosis in the toxemias of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1956;8:426–431.

19 Oliver M, Uchenik D. Bilateral exudative retinal detachment in eclampsia without hypertensive retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1980;90:792–796.

20 Bos AM, van Loon AJ, Ameln JG. Serous retinal detachment in preeclampsia. Ned Tijdschr Geneesjd. 1999;143:2430–2432.

21 Chatwani A, Oyer R, Wong S. Postpartum retinal detachment. J Reprod Med. 1989;34:842–844.

22 Bosco JAS. Spontaneous nontraumatic retinal detachments in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1961;82:208–212.

23 Brismar C, Schimmelpfennig W. Bilateral exudative retinal detachment in pregnancy. Acta Ophthalmol. 1989;67:699–702.

24 Sanchez JL, Ruiz J, Nanwani K, et al. Retinal detachment in preeclampsia and HELLP syndrome. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2003;78:335–338.

25 Burke JP, Whyte I, MacEwen CJ. Bilateral serous retinal detachments in the HELLP syndrome. Acta Ophthalmol. 1989;67:322–324.

26 Karaguzel H, Guven S, Karalezli A, et al. Bilateral serous retinal detachment in a woman with HELLP syndrome and retinal detachment. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;29:246–248.

27 Mendez-Figueroa H, Davidson C. Bilateral retinal detachments and preeclampsia: thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura or syndrome of haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelets? J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010;23:1268–1270.

28 Taskapili M, Kocabora S, Gulkilik G. Unusual ocular complications of the HELLP syndrome: persistent macular elevation and localized tractional retinal detachment. Ann Ophthalmol (Skokie). 2007;39:261–263.

29 Yamaguchi K, Fukuuchi Y, Nogawa S, et al. Recovery of decreased local cerebral blood flow detected by the xenon/CT CBF method in a patient with eclampsia. Keio J Med. 2000;49:71–74.

30 Neihaus L, Meyer BU, Hoffmann KT. Transient cortical blindness in EHP caused by cerebral vasospasm. Nervenartz. 1999;70:931–934.

31 Kesler A, Kaneti H, Kidron D. Transient cortical blindness in preeclampsia with indication of generalized vascular endothelial damage. J Neuroophthalmol. 1998;18:163–165.

32 Duncan R, Hadley D, Bone I, et al. Blindness in eclampsia: CT and MRI imaging. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1989;52:899–902.

33 Kaplan PW. Reversible hypercalcemic vasoconstriction with seizure and blindness: a paradigm for eclampsia. Clin Electroencephalogr. 1998;29:120–123.

34 Branch DW, Andres R, Digre KB, et al. The association of antiphospholipid antibodies with severe preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;73:541–545.

35 Do DV, Rismondo V, Nguyen QD. Reversible cortical blindness in preeclampsia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;134:916–918.

36 Hiruta M, Fukuda H, Hiruta A, et al. Emergency cesarean section in a patient with acute cortical blindness and eclampsia. Masui. 2002;51:670–672.

37 Apollon KM, Robinson JN, Schwartz RB, et al. Cortical blindness in severe preeclampsia: CT, MRI, and SPECT findings. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:1017–1019.

38 Davila M, Pensado A, Rama P, et al. Cortical blindness as symptom of preeclampsia. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim. 1998;45:189–200.

39 Shieh T, Kosasa TS, Tomai E, et al. Transient blindness in a preeclamptic patient secondary to cerebral edema. Hawaii Med J. 1996;55:116–117.

40 Beeson JH, Duda EE. CT scan demonstration of cerebral edema in eclampsia preceded by blindness. Obstet Gynecol. 1982;60:529–532.

41 Cunningham FG, Fernandez CO, Hernandez C. Blindness associated with preeclampsia and eclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172:1291–1298.

42 Akan H, Kucac M, Bolat O, et al. The diagnostic value of cranial CT in complicated eclampsia. J Belge Radiol. 1993;76:304–306.

43 Drislane FW, Wang AM. Multifocal cerebral hemorrhage in eclampsia and severe preeclampsia. J Neurol. 1997;244:194–198.

44 Wijman CA, Beijer IS, van Dijk GW, et al. Hypertensive encephalopathy: does not only occur at high blood pressure. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2002;146:969–973.

45 Leibowitz HA, Hall PE. Cortical blindness as a complication of eclampsia. Ann Emerg Med. 1984;13:365–367.

46 Borromeo CJ, Blike GT, Wiley CW, et al. Cortical blindness in a preeclamptic patient after a cesarean delivery complicated by hypotension. Anesth Analg. 2000;91:609–611.

47 Levavi H, Neri A, Zoldan J, et al. Preeclampsia, “HELLP” syndrome and postictal cortical blindness. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1987;66:91–92.

48 Ertan AK, Kujat CH, Jost WH, et al. HELLP syndrome-amausosis in sinus thrombosis with complete recovery. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 1994;54:646–648.

49 Ebert AD, Hopp HS, Entezami M, et al. Acute onset of blindness during labor: report of a case of transient cortical blindness in association with HELLP syndrome. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1999;84:111–113.

50 Crosby ET, Preston R. Obstetrical anesthesia for a parturient with preeclampsia, HELLP syndrome and acute cortical blindness. Can J Anaesth. 1998;45:452–459.

51 Tung CF, Peng YC, Chen Gh, et al. HELLP syndrome with acute cortical blindness. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2001;64:482–485.

52 Erbagci I, Karaca M, Ugur MG, et al. Ophthalmic manifestations of 107 cases with hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelet count syndrome. Saudi Med J. 2008;29:1160–1163.

53 Beck RW, Gamel JW, Willcourt RJ, et al. Acute ischemic optic neuropathy in severe preeclampsia. Am J Ophthalmol. 1980;90:342–346.

54 Sommerville-Lange LB. A case of permanent blindness due to toxemia of pregnancy. Br J Ophthalmol. 1950;34:431–434.

55 Wagener H. Lesions of the optic nerve and retina in pregnancy. JAMA. 1934;103:1910–1913.

56 Price J, Marouf L, Heine MW. New angiographic findings in toxemia of pregnancy. Ophthalmology. 1986;93(Suppl):125.

57 Brancato P, Menchini U, Bandello F. Proliferative retinopathy and toxemia of pregnancy. Ann Ophthalmol. 1987;19:182–183.

58 Curi AL, Jacks A, Pevisio C. Choroidal neovascular membrane presenting as a complication of preeclampsia in a patient with antiphospholipid syndrome. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:1080.

59 Theodossiadis PG, Kollia AK, Gogas P, et al. Retinal disorders in preeclampsia studied with optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;133:707–709.

60 Shaikh S, Ruby AJ, Piotrowski M. Preeclampsia related chorioretinopathy with Purtscher’s-like findings and macular ischemia. Retina. 2003;23:247–250.

61 Menchini U, Lanzetta P, Virgili G, et al. Retinal pigment epithelium tear following toxemia of pregnancy. Eur J Ophthalmol. 1995;5:139–141.

62 Leff SR, Yarian DR, Masciulli, et al. Vitreous hemorrhage as a complication of HELLP syndrome. Br J Ophthalmol. 1990;74:498.

63 Todd KC, Hainsworth DP, Lee LR, et al. Longitudinal analysis of central serous chorioretinopathy and sex. Can J Ophthalmol. 2002;37:405–408.

64 Normalina M, Zainal M, Alias D. Central serous choroidopathy in pregnancy. Med J Malaysia. 1998;53:439–441.

65 Khairallah M, Nouira F, Gharsallah R, et al. Central serous chorioretinopathy in a pregnant woman. J Fr Ophtalmol. 1996;19:216–221.

66 Quillen DA, Gass DM, Brod RD, et al. Central serous chorioretinopathy in women. Ophthalmology. 1996;103:72–79.

67 Sunness JS, Haller JA, Fine SL. Central serous chorioretinopathy and pregnancy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1993;111:360–364.

68 Gass JD. Central serous chorioretinopathy and white subretinal exudation in pregnancy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1991;109:677–681.

69 Fastenberg DM, Ober RR. Central serous choroidopathy in pregnancy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1983;101:1055–1058.

70 Chumbley LC, Frank RN. Central serous retinopathy and pregnancy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1974;77:158–160.

71 Cruysberg JR, Deutman AF. Visual disturbances during pregnancy caused by central serous choroidopathy. Br J Ophthalmol. 1982;66:240–241.

72 Bedrossian RH. Central serous retinopathy and pregnancy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1974;78:152.

73 Al-Mujaini A, Wali U, Ganesh A, et al. Natural course of central serous chorioretinopathy without subretinal exudates in normal pregnancy. Can J Ophthalmol. 2008;43:588–590.

74 Cunningham GF, MacDonald PC, Grant NF. Williams obstetrics, 19th ed. Norwalk, CT: Appleton & Lange; 1993. p. 224–5

75 Wiebers DO. Ischemic cerebrovascular complications of pregnancy. Arch Neurol. 1985;42:1106–1113.

76 Ayaki M, Yokoyama N, Furukawa Y. Postpartum CRAO simulating Purtscher’s retinopathy. Ophthalmologica. 1995;209:37–39.

77 LaMonica CB, Foye GJ, Silberman L. A case of sudden CRAO and blindness in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1987;69:433–435.

78 Lara-Torre E, Lee MS, Wolf MA, et al. Bilateral retinal occlusion progressing to longlasting blindness in severe preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:940–942.

79 Gull S, Prentice A. BRAO in pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1994;101:77–78.

80 Humayun M, Kattah J, Cupps TR, et al. Papillophlebitis and arteriolar occlusion in a pregnant woman. J Clin Neuroophthalmol. 1992;12:226–229.

81 Basu A, Eyong E. Cilioretinal arterial occlusion phenomenon: a rare cause of loss of vision in pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2008;137:251–252.

82 Blodi BA, Johnson MW, Gass JD, et al. Purtscher’s-like retinopathy after childbirth. Ophthalmology. 1990;97:1654–1659.

83 Vela JI, Diaz-Cascajosa J, Crespi J, et al. Protein S deficiency and retinal arteriolar occlusion in pregnancy. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2007;17:1004–1006.

84 Lanzetta P, Crovato S, Pirrachio A, et al. Retinal arteriolar obstruction with progestin treatment of threatened abortion. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2002;80:667–669.

85 Nelson ME, Talbot JF, Preston FE. Recurrent multiple branch retinal arteriolar occlusions in a patient with protein C deficiency. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1989;227:443–447.

86 Greven CM, Weaver RG, Owen J, et al. Protein S deficiency and bilateral branch retinal artery occlusion. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:33–34.

87 Bergh PA, Hollander D, Gregori CA, et al. Mitral valve prolapse and thromboembolic disease in pregnancy: a case report. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1988;27:133–137.

88 Kim IT, Choi JB. Occlusions of branch retinal arterioles following amniotic fluid embolism. Ophthalmologica. 2002;21:305–308.

89 Brown GC, Magargal LE, Shields JA. Retinal arterial obstruction in children and young adults. Ophthalmology. 1981;88:18–25.

90 Chung YR, Kim JB, Lee K, et al. Retinal artery occlusion in a healthy pregnant patient (unilateral BRAO). Korean J Ophthalmol. 2008;22:70–71.

91 Chew EY, Trope GE, Mitchell BJ. Diurnal intraocular pressure in young adults with central retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmology. 1987;94:1545–1549.

92 Gabsi S, Rekik R, Gritli N, et al. Occlusion of the central retinal vein in a 6-month pregnant woman. J Fr Ophtalmol. 1994;17:350–354.

93 Gonzalvo FJ, Abecia E, Pinilla I, et al. Central retinal vein occlusion and HELLP syndrome. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2000;78:596–598.

94 Rahman I, Saleemi G, Semple D, et al. Pre-eclampsia resulting in central retinal vein occlusion. Eye (Lond). 2006;20:955–957.

95 Bjerknes T, Askvik J, Albrechtsen S, et al. Retinal detachment in association with preeclampsia and abruptio placentae. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1995;60:91–93.

96 Cogan DG. Fibrin clots in the choriocapillaris and serous detachment of the retina. Ophthalmologica. 1976;172:298–307.

97 Martin VA. Disseminated intravascular coagulopathy. Trans Ophthalmol Soc UK. 1978;98:506–507.

98 Hoines J, Buettner H. Ocular complications of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) in abruptio placentae. Retina. 1989;9:105–109.

99 Patel N, Riordan-Eva P, Chong V. Persistent visual loss after retinochoroidal infarction in pregnancy-induced hypertension and disseminated intravascular coagulation. J Neuroophthalmol. 2005;25:128–130.

100 Benson DO, Fitzgibbons JF, Goodnight SH. The visual system in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Ann Ophthalmol. 1980;12:413–417.

101 Larcan A, Lambert H, Laprevote-Heully MC, et al. Acute choriocapillaris occlusions in pregnancy and puerperium. J Mal Vasc. 1985;10:213–219.

102 Coscas G, Gaudric A, Dhermy P, et al. Choriocapillaris occlusion in Moschowitz’s disease. J Fr Ophtalmol. 1981;4:101–111.

103 Sperry K. Amniotic fluid embolism. JAMA. 1986;255:2183–2203.

104 Chang M, Herbert WN. Retinal arteriolar occlusions following amniotic fluid embolism. Ophthalmology. 1984;91:1634–1637.

105 Kim IT, Choi JB. Occlusions of branch retinal arterioles following amniotic fluid embolisms. Ophthalmologica. 2000;214:305–308.

106 Fischbein FI. Ischemic retinopathy following amniotic fluid embolization. Am J Ophthalmol. 1969;67:351–357.

107 Cunningham GF, MacDonald PC, Grant NF. Williams obstetrics, 19th ed. Norwalk, CT: Appleton & Lange; 1993. p. 215

108 Holly EA, Aston DA, Ahn DK, et al. Uveal melanoma, hormonal and reproductive factors in women. Cancer Res. 1991;51:1370–1372.

109 Reese AB. Tumors of the eye, 2nd ed. New York: Hoeber Medical Division, Harper & Row; 1963. p. 366–70

110 Borner R, Goder G. Melanoblastoma der uvea and schwangerschaft. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd. 1966;149:684.

111 Frenkel M, Klein HZ. Malignant melanoma of the choroids in pregnancy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1966;62:910.

112 Pack GT, Scharnagel IM. The prognosis for malignant melanoma in the pregnant woman. Cancer. 1951;4:324.

113 Seddon JM, MacLaughlin DT, Albert DM, et al. Uveal melanomas presenting during pregnancy and the investigation of oestrogen receptors in melanomas. Br J Ophthalmol. 1982;66:695.

114 Siegel R, Amslie WH. Malignant ocular melanoma during pregnancy. JAMA. 1963;185:542.

115 Lee CS, Yang WI, Shin KJ, et al. Rapid growth of choroidal melanoma during pregnancy. Acta Ophthalmol. 2011;89(3):e290–e291.

116 Foss AJ, Alexander RA, Guille MJ, et al. Estrogen and progesterone receptor analysis in ocular melanomas. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:431–435.

117 Behrens T, Kaerlev L, Cree I, et al. Hormonal exposures and the risk of uveal melanoma. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21:1625–1634.

118 Shields CL, Shields JA, Eagle RC, et al. Uveal melamona and pregnancy. A report of 16 cases. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:1667–1673.

119 Romanowska-Dixon B. Melanoma of choroids during pregnancy:case report. Klin Oczna. 2002;104:395–397.

120 Egan KM, Quinn JL, Gragoudas ES. Childbearing history associated with improved survival in choroidal melanoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117:939–942.

121 Egan KM, Walsh SM, Seddon JM, et al. An evaluation of reproductive factors on the risk of metastases from uveal melanoma. Ophthalmology. 1993;100:1160–1166.

122 Gass JD. Stereoscopic atlas of macular diseases: a funduscopic and angiographic presentation, 4th ed. St Louis: Mosby; 1997. p. 218–19

123 Gass JD. Stereoscopic atlas of macular diseases: a funduscopic and angiographic presentation, 4th ed. St Louis: Mosby; 1997. p. 693–5

124 Gass JDM. Stereoscopic atlas of macular diseases: a funduscopic and angiographic presentation, 3rd ed. St Louis: Mosby; 1987. p. 512–3

125 Gass JD. Stereoscopic atlas of macular diseases: a funduscopic and angiographic presentation, 4th ed. St Louis: Mosby; 1997. p. 752–4

126 Gass JDM. Stereoscopic atlas of macular diseases: a funduscopic and angiographic presentation, 3rd ed. St Louis: Mosby; 1987. p. 380–3

127 Oday MP, Nielsen P, Al Bozom I. Orbital rhabdomyosarcoma metastatic to the placenta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171:1382–1383.

128 Marsh RW, Chu NM. Placental metastasis from primary ocular melanoma: a case report. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174:1654–1655.

129 Bendon RW, Mimouni F, Khouri J, et al. Histopathology of spontaneous abortion in diabetic pregnancies. Am J Perinatol. 1990;7:207–210.

130 Mills J, Simpson JL, Driscoll SG, et al. Incidence of spontaneous abortion among normal women and insulin-dependent diabetic women whose pregnancies were identified within 21 days of conception. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:1617–1623.

131 Miller E, Hare JW, Cloherty JP, et al. Elevated maternal hemoglobin A1c in early pregnancy and major congenital anomalies in infants of diabetic mothers. N Engl J Med. 1981;304:1331–1334.

132 Klein BK, Klein RK, Meuer SM, et al. Does the severity of diabetic retinopathy predict pregnancy outcome? Diabetic Compl. 1988;2:179.

133 Jovanovic R, Jovanovic L. Obstetric management when normoglycemia is maintained in diabetic pregnant women with vascular compromise. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1984;149:617–623.

134 Sunness JS. The pregnant woman’s eye. Surv Ophthalmol. 1988;32:219–238.

135 Diabetes in Early Pregnancy Study GroupChew EY, James LM, Metzger BE. Metabolic control and progression of retinopathy. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:631–637.

136 Laatikainen L, Teramo K, Hieta-Heikurainen H, et al. A controlled study of the influence of continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion treatment on diabetic retinopathy during pregnancy. Acta Med Scand. 1987;221:367–376.

137 The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. The effect of intensive diabetes treatment on the progression of diabetic retinopathy in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995;113:36.

138 Chang S, Fuhrmann M, the Diabetes in Early Pregnancy Study Group. Pregnancy, retinopathy, normoglycemia: a preliminary analysis. Diabetes. 1985;34(suppl):39.

139 KROC Collaborative Study Group. Blood glucose control and the evaluation of diabetic retinopathy and albuminuria. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:365.

140 Kentucky Diabetic Retinopathy Group. Guidelines for eye care in patients with diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149:769–770.

141 Cunningham GF, MacDonald PC, Grant NF. Williams obstetrics, 19th ed. Norwalk, CT: Appleton & Lange; 1993. p. 763–807

142 Chen HC, Newsom RSB, Patel V. Retinal blood flow changes during pregnancy in women with diabetes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994;35:3199–3208.

143 Loukovaara S, Kaaja R, Immonen I. Macular capillary blood flow velocity by blue-field entoptoscopy in diabetic and healthy women during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Greafes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2002;240:977–982.

144 Loukovaara S, Harju M, Kaaja R, et al. Retinal capillary blood flow in diabetic and nondiabetic women during pregnancy and postpartum period. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:1486–1491.

145 Hellstedt T, Kaaja R, Teramo K, et al. Macular blood flow during pregnancy in patients with early diabetic retinopathy measured by blue-field entoptic stimulation. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1996;234:659–663.

146 Schocket LS, Grunwald JE, Tsang AF, et al. The effect of pregnancy on retinal hemodynamics in diabetic versus nondiabetic mothers. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;128:477–484.

147 Lauszus FF, Klebe JG, Bek T, et al. Increased serum IGF-1 during pregnancy is associated with progression of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes. 2002;52:852–856.

148 Gibson JM, Westwood M, Lauszus FF, et al. Phosphorylated insulin-like growth factor binding protein 1 is increased in pregnant diabetic subjects. Diabetes. 1999;48:321–326.

149 Khaliq A, Foreman D, Ahmed A, et al. Increased expression of placenta growth factor in proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Lab Invest. 1998;78:109–116.

150 Spirin KS, Saghizadeh M, Lewin SL, et al. Basement membrane and growth factor gene expression in normal and diabetic human retinas. Curr Eye Res. 1999;18:490–499.

151 Best RM, Hayes R, Hadden DR, et al. Plasma levels of endothelin-1 in diabetic retinopathy in pregnancy. Eye. 1999;13:179–182.

152 Hill DJ, Flyvbjerg A, Arany E, et al. Increased levels of serum fibroblast growth factor-2 in diabetic pregnant women with retinopathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:1452–1457.

153 Castellon R, Hamdi HK, Sacerio I, et al. Effects of angiogenic growth factor combinations on retinal endothelial cells. Exp Eye Res. 2002;74:523–535.

154 Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. Effect of pregnancy on microvascular complications in the diabetes control and complications trial. Diabetes Care. 2000;24:1084–1091.

155 Soubrane G, Canivet J, Coscas G. Influence of pregnancy on the evolution of background retinopathy: preliminary results of a prospective fluorescein angiography study. In: Ryan JJ, Dawson AK, Little HL. Retinal diseases. New York: Grune & Stratton; 1985:15–20.

156 Ayed S, Jeddi A, Dagfous F, et al. Aspects evolutifs de la retinopathie diabetique pendant la grosse. J Fr Ophtalmol. 1992;15:474.

157 Moloney JM, Drury MI. The effect of pregnancy on the natural course of diabetic retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1982;93:745.

158 Klein BK, Mosse SE, Klein R. Effect of pregnancy on progression of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care. 1990;13:34.

159 Serup L. Influence of pregnancy on diabetic retinopathy. Acta Endocrinol. 1986;277:122.

160 Kaaja R, Sjoberg L, Hellsted T, et al. Long-term effects of pregnancy on diabetic complications. Diabet Med. 1996;13:165–169.

161 Hemachandra A, Ellis D, Lloyd CE, et al. The influence of pregnancy on IDDM complications. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:950–954.

162 Klein BK, Klein R. Gravity and diabetic retinopathy. Am J Epidemiol. 1984;119:564.

163 Lipman MJ, Kranias G, Bene CH, et al. The effect of multiple pregnancies on diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmology. 1993;100:141.

164 Chaturvedi N, Stephenson JM, Fuller JH. The relationship between pregnancy and long-term maternal complications in the EURODIAB IDDM complications study. Diabetic Med. 1995;18:950–954.

165 Aiello LM, Rand LI, Briones JC, et al. Nonocular clinical risk factors in the progression of diabetic retinopathy. In: Little HL, Jack RL, Patz A, et al. Diabetic retinopathy. New York: Thieme-Stratton; 1983:21–32.

166 Dibble CM, Kochenour NK, Wocley RJ, et al. Effect of pregnancy on diabetic retinopathy. Obstet Gynecol. 1982;59:699.

167 Rosenn B, Miodovnik M, Kranias G, et al. Progression of diabetic retinopathy in pregnancy: association with hypertension. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166:1214.

168 Beetham WP. Diabetic retinopathy in pregnancy. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc.. 1950;48:205.