CHAPTER 13 Pregnancy: First Trimester

The state of a woman’s health is indeed completely tied up with the culture in which she lives and her position in it, as well as in the way she lives her life as an individual. We cannot hope to reclaim our bodily wisdom and inherent ability to create health without first understanding the influence of our society on how we think and care for our bodies.1

PREGNANCY CARE AND PRENATAL WELLNESS

The past decades have tremendously improved the outcomes of high-risk pregnancies and birth, yet with these improvements have come the ubiquitous presence of technological intervention in nearly all aspects of normal childbearing as well. Yet, the safety and efficacy of the routine use of many interventions is not clear, with a striking lack of an evidence base for many.2,3 Nonetheless, the number and frequency of interventions has risen steadily since the 1950s. Since 2003, cesarean section has been the most common hospital surgical procedure performed in the United States, with 1.2 million of these major abdominal surgeries each year, accounting for more than 25% of all US births at a national cost $14.6 billion in total charges. In spite of spending more money and using more technologies on obstetric care than any other country in the world, the United States ranks only 25th in birth outcome and infant mortality worldwide. Dr. Marsden Wagner, former Director of the World Health Organization’s (WHO) European Regional Office, remarked at an international medical conference that hospital births “endanger mothers and babies—primarily because of the impersonal procedures and overuse of technology and drugs.”4

The desire to avoid excessive technology and an inclination toward natural approaches to health, combined with many women’s perceptions that obstetric care is grossly impersonal, has led women to seek alternatives to conventional obstetric care. Homebirth has become an increasingly popular option because of its astounding safety record and the intimate prenatal, birth, and postnatal care experience it offers women. 5 6 7 8 9 Many choose to self-medicate with alternative therapies, such as herbs, and turn to sources that may not be reliable for information. Although the treatment of common pregnancy complaints with gentle herbs and simple home remedies has generally proved safe, women are increasingly seeking advice through the Internet, books, and alternative practitioners for potentially serious problems than can arise during the childbearing cycle. Thus, it is essential for practitioners to become knowledgeable about natural therapies and willing to have an open dialog with their clients about their concerns and preferences in order to help pregnant women access intelligent and accurate information about the safety and efficacy of such therapies during the childbearing cycle, and to avoid harmful therapies and obtain appropriate medical care as needed.

DIET, NUTRITION, EXERCISE, LIFESTYLE AND PSYCHOEMOTIONAL HEALTH: CENTRAL TO OPTIMAL CHILDBEARING HEALTH

HERBS AS PART OF PREGNANCY WELLNESS

Schools of thought differ on whether herbs should be used routinely—or at all—during pregnancy. Some ascribe to the belief that because most herbs have not been proven safe for use during pregnancy, they should be entirely avoided, whereas others see certain herbs more as foods that can provide an additional source of nutrition during pregnancy, or as tonics that can encourage and support optimal pregnancy health and uterine function.10,11 Many consider the choice of whether herbs are appropriate for use during pregnancy to be circumstantial, for example, dependent upon the nature of the condition being treated and the risk benefit of herbs compared with medical intervention for that particular condition. Certain conditions are beyond the scope of herbal treatment, and practitioners should be keenly aware of the symptoms that herald such conditions and indicate the absolute need for medical care (Box 13-1).

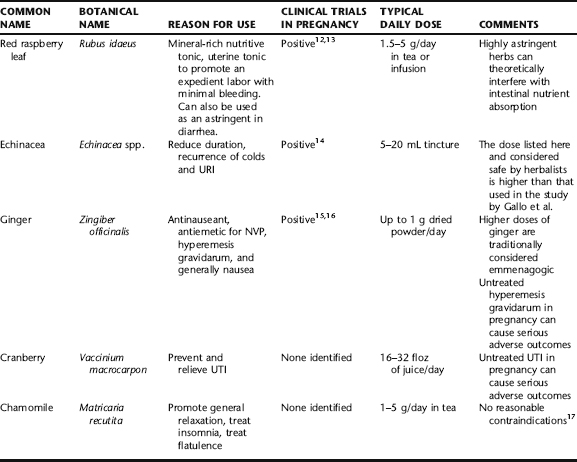

It can be useful to see herbs on a continuum between food and medicine. There are many herbs whose constituents are mostly benign, nutritive substances such as carbohydrates vitamins, and minerals (Table 13-1). 12 13 14 15 16 17 Herbs such as nettles (Urtica dioica), milky oats (Avena sativa), and red raspberry leaf (Rubus idaeus) are examples. On the other hand, there are numerous herbs whose use in pregnancy is entirely contraindicated for safety reasons (see Chapter 12). Somewhere between these categories are herbs not appropriate for daily, routine intake, but which can be used if necessary for brief or more extended periods of time for specific conditions. In addition to common complaints of pregnancy, pregnant and lactating women are also subject to the run of the mill complaints and illnesses we all face—colds, indigestion, headache, etc.—for which they may seek herbal care. Many of these problems can be addressed safely and gently with the herbs listed in the following or discussed in subsections of this chapter.

Table 13-1 provides an overview of a number of herbs that are generally considered safe for general use during pregnancy, reasons for use, and dose. The remainder of this chapter is dedicated to common pregnancy complaints and problems, and the herbs that are often used in their treatment.

THE ROLE OF HERBS IN THE PREVENTION AND TREATMENT OF MISCARRIAGE

Miscarriage, medically referred to as spontaneous abortion (SAb), is the spontaneous, unexpected, and often unexplained loss of a pregnancy before 20 weeks gestation. Miscarriage is the most common pregnancy complication; however, the exact incidence is unknown because the actual incidence of conception in the population is uncertain. One in seven clinically recognized pregnancies will miscarry, and in studies of women attempting to conceive, spontaneous abortion occurs in 10% to 15% of conceptions. 18 19 20 Based on studies of pregnancies achieved through assisted reproductive technologies, 50% of conceptions result in miscarriage. Miscarriage rate is related to maternal age, with rates under 2% for women under 30 years of age, and between 5% and 10% for women more than 40 years old. Miscarriage rates decline to less than 3% if there is a healthy fetus present at 8 weeks gestation (as visible upon ultrasonogram) in healthy women. Note: The term fetus is used throughout this chapter; however, the term embryo is the technically correct developmental term for any baby less than or equal to 8 weeks of gestation.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF MISCARRIAGE

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Bleeding in early pregnancy can be a sign of serious problems. Major causes of early pregnancy bleeding, other than miscarriage, that must be ruled out include ectopic pregnancy and cervical, vaginal, or uterine pathology (e.g., trauma, polyp, cervicitis, or neoplasia). Molar pregnancy (hydatidiform mole) also should be ruled out. Some women experience a small amount of bleeding on implantation, known as physiologic bleeding, which typically is not of concern.

CATEGORIES OF MISCARRIAGE

CONVENTIONAL TREATMENT APPROACHES

Conventional treatment of inevitable miscarriage includes hospital admission for pain medication if needed, and ultrasound to determine whether the fetus is alive or whether miscarriage is incomplete. In incomplete abortion where there has been substantial blood loss, appropriate emergency procedures are followed, including resuscitation if needed, administration of intravenous fluids, blood work, and treatment of shock and infection is present. A dilatation and evacuation is performed to empty the uterus of any remaining products of conception and medication for pain and infection prophylaxis is administered as appropriate. In cases of missed abortion, typically first identified during routine ultrasound examination, or attention to a discrepancy between maternal growth or subjective or objective pregnancy signs and time elapsed since the missed period, a wait and see attitude may be adopted for up to several days to 2 weeks (depending upon the time elapsed since the missed abortion first occurred) to see if completion of the abortion ensues spontaneously, or surgical removal of the conception products may be scheduled to prevent the risk of hemorrhage and infection.

BOTANICAL TREATMENT FOR MISCARRIAGE: THREATENED AND HABITUAL

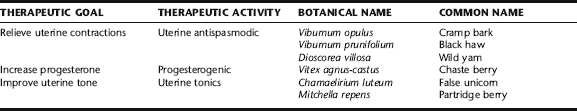

This section provides botanical strategies for miscarriage prevention in the event of threatened miscarriage (Table 13-2), and basic support for habitual abortion when resulting from progesterone insufficiency. If fetal demise has been confirmed by ultrasound, readers may follow the protocol in the example in the case history at the end of the chapter. When there is incomplete or missed abortion, special attention needs to be given to the risk of infection and subsequent coagulopathy. Women who miscarry are at some increased risk for postmiscarriage anxiety and depression. Emotional support during and after a miscarriage, as well as during a subsequent pregnancy, is often necessary. Botanical treatments for postpartum depression (see Chapter 18) can be extrapolated for use when needed.

TABLE 13-2 Botanical Treatment Strategies for Miscarriage Prevention in the Event of Threatened Miscarriage and Habitual Abortion

| Chaste berry | (Vitex agnus castus) | 50 mL |

| Cramp bark | (Viburnum opulus) | 30 mL |

| Partridge berry | (Mitchella repens) | 20 mL |

| Total: 100 mL | ||

Herbalist/Midwife Protocol for Threatened Miscarriage with Cramping as the Primary Symptom

| Cramp bark * (Viburnum opulus) | 70 mL |

| Wild yam (Dioscorea villosa) | 30 mL |

| Total: 100 mL |

* Black haw (Viburnum prunifolium) may be used interchangeably with cramp bark.

miscarriage prevention with uterine irritability and progesterone insufficiency, which is treated with long-term use of chaste berry (Vitex agnus-castus) begun several months prior to conception and continued until several weeks past the time of prior miscarriage, and accompanied by cramp bark or black haw, and wild yam once pregnancy is established to prevent cramping. Uterine tonic herbs, particularly partridge berry (Mitchella repens) and false unicorn root (Chamaelirium luteum), are commonly included in formulae as well. False unicorn is an endangered herb, therefore, it is recommended to use only cultivated sources. Traditional Chinese medicine can play an important role in miscarriage prevention when there is habitual abortion, as its constitutional diagnostic model and corresponding herbal and dietary protocol can be specifically tailored to a woman’s constitution and imbalances.

In case of threatened miscarriage, the Western herbal practitioner will need to address commonly overlooked factors, such as overwhelming stress, dehydration, or malnutrition. Urinary tract infection (or other infection) should be ruled out, and if present, treated (see Chapter 10). Women should attempt to achieve an optimal body weight prior to conception with underweight women, particularly trying to bring their weight to within a normal body mass index to ensure adequate hormone production. Herbs can be used primarily to reduce uterine contractions associated with threatened miscarriage. The most commonly used herbs include cramp bark (Fig. 13-1), black haw, and wild yam, either alone or in combination.

Black Haw, Cramp Bark, and Wild Yam

When there is uterine cramping in the absence of cervical dilatation, cramp bark (Viburnum opulus) and black haw (Viburnum prunifolium) are used to arrest uterine spasm.49,50 These herbs, which can be used interchangeably or together for this purpose, have a long history of use as spasmolytics during pregnancy, especially for miscarriage, dating back well over a hundred years by Western herbalists, and even longer by Native American tribes.49,50 Black haw was official in the United States Pharmacopoeia in 1882, its uses as an antispasmodic and preventative for miscarriage popularized by the Eclectic physicians. Cramp bark is included in the British Herbal Pharmacopoeia and is used by herbalists in the United Kingdom for miscarriage prevention.17,49 The active principles are unknown; however, it is thought that at least four active substances, including scopoletin and aesculetin, which have been identified, have uterine spasmolytic activity.51

Another herb with a long history of use for relieving uterine contractions is wild yam (Dioscorea villosa). Although this herb has developed the erroneous reputation for use as a progesterone supplement, wild yam in fact contains no progesterone, nor can it be converted by the body into progestogenic substances. However, this does not preclude its efficacy and reliability as a uterine antispasmodic, combining well both cramp bark and black haw; although, no research was identified that either supports or refutes its traditional uses.17

Chaste Tree

Chaste tree (Vitex agnus-castus) is used by midwives and herbalists to prevent miscarriage associated with low progesterone, where it may exert its effects via enhancing corpus luteum function.52,53 Although researchers are still uncertain as to the exact mechanism of action of vitex it appears to having a regulatory effect on luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), and progesterone, as well as the ability to reduce elevated prolactin levels via dopaminergic activity, and has shown positive effects in improving premenstrual syndrome symptoms and luteal phase defects. 53 54 55 56 57 58 It is used alone and in conjunction with topical USP progesterone when the latter is prescribed by an obstetrician or midwife for miscarriage prevention. Placebo-controlled studies for teratogenicity and mutagenicity were conducted in rats, and even when the animals were administered 74 times the dose typically consumed by humans, no toxicity nor aberrations in fetal development were seen.53 Although it is sometimes given acutely, for the herb to have efficacy as a miscarriage preventative, it is ideally given for at least 3 months prior to conception and continued well into the first trimester to maintain stable progesterone levels. The most recent edition of the Botanical Safety Handbook provides no contraindications to use during pregnancy.

Treatment Protocol: Missed Abortion

| Cotton root bark | (Gossypium herbaceum) | 40 mL |

| Black cohosh | (Actaea racemosa) | 40 mL |

| Blue cohosh | (Caulophyllum thalictroides) | 20 mL |

| Total: 100 mL | ||

Instructions: Beginning in the morning, take 2.5 mL every hour for 4 hours, and then discontinue. She was instructed that if no contractions commenced, she was to repeat the next day as for day 1. If no contractions ensue on day 2, discontinue on the third day, and resume for two more days on days 4 and 5.

Treatment Protocol: Miscarriage Prevention

| Chaste berry | (Vitex agnus castus) | 60 mL |

| Cramp bark | (Viburnum opulus) | 30 mL |

| Wild yam | (Dioscorea villosa) | 20 mL |

| Total: 100 mL | ||

NAUSEA AND VOMITING OF PREGNANCY AND HYPEREMESIS GRAVIDARUM

Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy (NVP), generally referred to as “morning sickness,” is a common pregnancy discomfort. Its association with pregnancy was documented on papyrus dating as far back as 2000 bce. The earliest reference is in Soranus’ Gynecology from the 2nd century ce.59 Some degree of nausea, with or without vomiting, occurs in 50% to 90% of all pregnancies. It generally begins at about five to six weeks of gestation and usually abates by 16 to 18 weeks gestation. As many as 15% to 20% of pregnant women will continue to experience some degree of NVP into the third trimester, and approximately 5% will continue to experience it until birth.60,61 The socioeconomic impact of NVP on time lost from either paid employment or household work is substantial, with one study reporting as many as 8.6 million hours of paid employment and 5.8 million hours of household work lost each year because of NVP.62 Additionally, women experiencing more extreme versions of NVP or hyperemesis gravidarum are vulnerable to social isolation, and possibly depression, as a result of their symptoms—they are simply too ill to engage in their normal social activities, or they isolate themselves in order to avoid the embarrassment of being caught vomiting publicly.63

Morning sickness is actually a misnomer for this condition, as the symptoms are not limited to the morning, and may occur at any time of day. In fact, in 80% of women, symptoms persist throughout the day. It has been jokingly said the condition is called morning sickness because it starts in the morning and lasts all day. Both the etiologies and role of NVP in pregnancy remain uncertain. Several physiologic etiologies have been proposed. It has been suggested that NVP actually serves a protective function for the pregnancy. Flaxman and Sherman propose, for example, that morning sickness causes women to avoid foods that might be dangerous to themselves or their embryos, especially foods that, prior to widespread refrigeration, were likely to be heavily laden with microorganisms and their toxins.64 Studies have demonstrated that women who experience some degree of NVP are less likely to miscarry or experience stillbirth.64,65

SYMPTOMS OF NVP AND HYPEREMESIS GRAVIDARUM

Symptoms of hyperemesis gravidarum include persistent vomiting (and often dry heaving as well) accompanied by weight loss exceeding 5% of prepregnancy body weight and ketonuria unrelated to other causes.66 It is generally incapacitating. It is estimated that hyperemesis occurs in 0.3% to 2% of pregnancies.67 Hyperemesis typically persists into the second trimester, and may continue until the time of birth. Hospitalization for hyperemesis is common, peaking at approximately 9 weeks gestation and leveling off at around 20 weeks. The pathogenesis of hyperemesis is unknown. Symptoms generally resolve by midpregnancy regardless of treatment. When properly treated, hyperemesis gravidarum is associated with a very low morbidity and mortality rate. Without adequate treatment, the mother may experience micronutrient deficiency, Wernicke’s encephalopathy caused by vitamin B1 deficiency, and consequences of malnutrition, for example, propensity toward infection or slow healing wounds. There does not appear to be an increased risk of birth defects in babies born to mothers with hyperemesis gravidarum, and although women with hyperemesis gravidarum may experience substantial weight loss in early pregnancy, as long as overall pregnancy weight gain is normal, there does not appear to be any difference in birth weight in women with hyperemesis gravidarum. 68 69 70 71 Low birth weight is likely to occur in babies born to mothers who do not make up their pregnancy weight later in pregnancy.67,68, 72 73 74

RISK FACTORS FOR NVP AND HYPEREMESIS GRAVIDARUM

In a study of the risk factors for NVP and hyperemesis, hyperthyroid disorders, psychiatric illness, previous molar pregnancy, pre-existing diabetes, gastrointestinal disorders, and asthma were all statistically significant risks, whereas maternal smoking and maternal age older than 30 were associated with decreased risk. Singleton female pregnancies, as well as multiple pregnancies, were associated with statistically significant increased risk of hyperemesis.75 Women with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) are more likely to experience NVP and hyperemesis. During pregnancy, esophageal, gastric, and small bowel motility are impaired as a result of smooth muscle relaxation fostered by increased levels of female sex hormones. This dysmotility could contribute to NVP. Hormonal changes leading to changes in lower esophageal tone may also lead NVP, in addition to heartburn.76,77 Psychological factors, particularly feelings of ambivalence about the pregnancy, have been suggested as part of the etiology; however, this theory has not been borne out by psychological evaluation of women with this condition, and studies are confounded by the fact that the experience of hyperemesis can lead to feelings of ambivalence.78 Elevated serum concentrations of estrogen and progesterone have been implicated as pathogenic factors, as have decreased prolactin levels and elevated human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG); however, none of these associations has been definitely demonstrated.79 Other proposed pathogenic factors include abnormal gastric motility, nutrient deficiencies, alterations in lipid levels, changes in the autonomic nervous system, genetic factors, and infection with Helicobacter pylori. 80 81 82 83

DIAGNOSIS

There is no specific diagnosis for NVP. Nausea, accompanied by a missed menstrual period, or other confirmation of pregnancy, is usually adequate. Hyperemesis gravidarum, likewise, is a clinical diagnosis. There is not a definitive point of demarcation separating a diagnosis of NVP from hyperemesis. The sheer persistence of the vomiting accompanied, as mentioned, by weight loss exceeding 5% of prepregnancy body weight and ketonuria unrelated to other causes is considered diagnostic.66 Although NVP can cause significant inconvenience and changes in daily activities, hyperemesis is usually markedly debilitating, and many practitioners consider persistent vomiting and marked debility diagnostic of hyperemesis. Women with persistent vomiting are evaluated by ultrasound for the presence of trophoblastic disease (e.g., hydatidiform mole) and multiple pregnancy. Serum electrolyte levels, as well as FT4 are also checked. Differential diagnosis for nausea and vomiting is extensive; other pathologic causes ranging from endocrine disorders to neoplastic conditions should be ruled out, particularly for nausea and vomiting that commence after 10 weeks gestation. Concurrent signs such as abdominal pain, fever, headache, goiter, abnormal neurologic findings, diarrhea, constipation, or hypertension suggest a problem other than NVP or hyperemesis gravidarum. Nausea and vomiting that occur in the latter half of pregnancy could be associated with preeclampsia, HELLP syndrome (hemolysis, elevated liver function tests, low platelets), and fatty liver of pregnancy, and should be ruled out.

CONVENTIONAL TREATMENT OF NVP AND HYPEREMESIS GRAVIDARUM

Conventional treatment for both NVP and hyperemesis gravidarum includes supportive therapy, nonpharmacologic, and pharmacologic interventions. Nausea that is mild and self-limiting is considered normal, and does not require treatment.63 The supportive and nonpharmacologic therapies used in conventional care are the same as those used in conjunction with botanical care, and are described under Nonpharmacologic Treatment of NVP and Hyperemesis gravidarum. Pharmacologic treatment may be necessary in severe or refractory cases, and after nonpharmacologic interventions have failed to bring relief or improvement, in order for women to function in their daily lives and gain nutrition without IV or enteral feeding methods.

The mainstay of pharmacologic treatment for these conditions is the use of antiemetic drugs.68,84,85 Antiemetics have been shown to be more effective than placebo, and do not appear to increase birth defect risk; however, evidence of safety from well-designed trials is not substantial.86 Thus, many women and doctors remain wary of their use, especially in the first trimester. Most women are content to wait out the normal, mild to moderate first trimester nausea without significant intervention as long as it does not interfere with their ability to function.

When pharmacologic intervention is required, it is advisable to start with drugs with minimal known side effects, and progress to other drugs only if these are ineffective and antiemetic therapy is necessary.87 Antihistamines are also successfully used as antiemetics to control NVP.86 A meta-analysis reviewed 24 controlled studies including over 200,000 first trimester exposures and found that these medications had a protective effect, with a reduction in birth defects.85 A number of other antiemetic medications are used including several of the dopamine antagonists, appear to be helpful and are not associated with teratogenicity.86

Corticosteroids have been used for women with severe, unresponsive hyperemesis. The mechanisms of action are poorly understood, and the results of controlled trials have been contradictory.86, 88 89 90 91 92 Prolonged use of oral corticosteroids in pregnancy may increase the risk of preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM), as well as the risk of cleft palate, the latter when administered prior to 10 weeks of gestation.93,94 Given the potential risks and undetermined benefits, ACOG advises against the use of corticosteroids for treatment of hyperemesis unless as a last resort.95

NONPHARMACOLOGIC TREATMENT OF NVP AND HYPEREMESIS GRAVIDARUM

Mazotta et al. conducted an extensive review of MEDLINE, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and bibliographies and texts for the effectiveness of maternal therapies for NVP (including randomized controlled trials of drug treatment versus placebo or no therapy, or another drug therapy). The researchers focused on observational, controlled studies for adverse fetal effects, specifically, the incidence of major malformations, because treatment of NVP usually involves administration of medication during the first trimester. Physical outcome measures were evaluated. The findings indicated that some women prefer more “natural,” nonpharmacologic therapies for NVP, such as dietary and lifestyle changes, pyridoxine, ginger, and/or stimulation of the P6 Neiguan point (e.g., Seabands). Theoretically, these therapies are not considered harmful to the fetus.96 The goals of nonpharmacologic treatment for both NVP and hyperemesis gravidarum include reducing the symptoms and enabling the mother to obtain nutrition from foods and fluids. Malnutrition and dehydration are both significant concerns when there is a near complete inability to eat or drink, or when there is persistent vomiting.

Nutrition: Food and Fluids

Trigger Avoidance

Women with hyperolfaction are especially prone to NVP and hyperemesis. Avoiding triggers of nausea and/or vomiting, for example, offending smells or tastes can be helpful. This can be difficult to effectively achieve as preferences and aversions are continually changing for the pregnant woman, and are highly individual. It is for this reason that simple comfort measures, such as dry crackers, ginger ale, and so forth, may only yield fleeting results. Many women with NVP find that most measures only work for a limited time, often for a few consecutive days, and that the very substance that led to some improvement may often then join the ranks of the offending agents. For some women, teeth brushing is a major trigger, stimulating gagging or vomiting. Avoiding brushing when nauseated can help, and using a toothpaste that is low-foaming and with a mild minty flavor can help minimize an adverse response. Some women find foregoing the toothpaste altogether for a time can be helpful. Using a child’s sized toothbrush, and avoiding getting the brush, toothpaste, or “spit” in the back of the mouth can be helpful. Many women find the sight of certain foods distasteful enough to trigger nausea or vomiting; for example, the meat or fish department of the market. Avoiding these departments or having someone else do the grocery shopping until intolerable nausea has passed, can reduce trigger exposure. Iron-containing supplements cause gastric irritation, and thus should be avoided until NVP or hyperemesis is overcome. Women with very severe NVP or hyperemesis may be triggered by even the thought or the mention of food. In such cases, avoiding exposure to all food images may be necessary. Additional triggers include stuffy rooms, odors (e.g., perfume, chemicals, smoke), heat, humidity, noise, and visual or physical motion (e.g., flickering lights, driving), and inadequate rest.97,98

Protein and Carbohydrates

Avoid hypoglycemia by eating small, regular meals or snacks, including immediately upon waking in the morning, and prior to bed and even during the night, if necessary. Women with mild to moderate nausea, with or without minimal vomiting, often respond to intake of dry, slightly salty foods, for example, crackers, toast, and pretzels, as well as high-protein foods.41 Many women find that eating simple, carbohydrate-based meals, for example, a baked potato or plain pasta with a small amount of butter and salt, can be easily digested and allay nausea. A small amount of slightly sweetened yogurt is often a tolerable snack, and can easily be eaten at any time of day (or night).

Intravenous Fluid and Nutrient Replacement

Should oral fluid or food intake be impossible to achieve, and a nutritive enema either ineffective or an undesirable treatment to the mother, IV nutrition will be necessary. Infusion of intravenous Lactated Ringer’s solution supplemented with electrolytes and vitamins can relieve symptoms of dehydration in 1 to 2 days.61 Minerals including magnesium, phosphorus, and potassium need to be supplemented, and 100 mg IV thiamine for 2 to 3 days is recommended for women who have vomited for greater than 3 weeks.61 Plasma sodium should be corrected at a careful rate to avoid osmotic demyelination syndrome, which can occur with too quick a replacement.

Nutrient Supplements

Pyridoxine (vitamin B6), 10 to 25 mg by mouth, three to four times daily, has been demonstrated to improve mild to moderate nausea in women with NVP, although it does not seem to be effective in the treatment of vomiting.84,100,101

Acupuncture/Acupressure

A number of studies have been published demonstrating the effectiveness of acupuncture and acupressure for the suppression and relief of nausea and vomiting, including NVP. 102 103 104 105 106 Treatment has focused on what is referred to in TCM as the Neiguan point, pericardium 6 (P6), an acupuncture point on the underside of the wrist. Acupuncture has been systemically tested in a limited number of trials. A single-blind, randomized, controlled trial in which 593 women less than 14 weeks with nausea and vomiting were treated weekly for 4 weeks found no difference in vomiting but less nausea and dry retching in treatment women versus controls. Although acupuncture clearly seems to be effective, it requires administration by a trained acupuncturist, regular access to which is a limitation for many women, and shows no apparently greater benefit than acupressure, which women can self-administer. Further, acupuncture treatment requires ongoing visits, which incur a much greater cost than the one-time purchase of acupressure bands, which can be used repeatedly.107

In one study, researchers randomly assigned 33 women with hyperemesis gravidarum to acupuncture treatments on P6 or to mock treatments at a different location. After 2 days, all treatments were stopped for an additional 2 days to allow any effects to dissipate. The groups were then reversed for two additional days of treatment. Before treatment, all women were vomiting. On day 3, only 7 out of 17 women (41%) receiving active acupuncture were still vomiting compared with 12 out of 16 (75%) receiving mock treatment. After the active and mock treatment groups were switched, more of the women in the active treatment group ceased vomiting. The women in the active treatment group also reported decreased nausea.46 In another study, reported in the Journal of Reproductive Medicine, 41 patients were treated with acustimulation of P6 with an acustimulation device at the Department of Maternal-Fetal Medicine at Eastern Virginia Medical School.108 Prior to treatment, patients averaged a score of 4.2 on a nausea severity scale, with 5 being completely debilitating nausea. Posttreatment device effectiveness averaged 4.2, with significant or complete relief rated 5. All neonates were evaluated for congenital abnormalities and all neonates were found to be normal. The researchers concluded that because current pharmacologic treatments for nausea in early pregnancy are not consistent, efficacious, or without unwanted side effects or increased teratogenic risks, acustimulation of P6 in pregnancy may prove to be a significant therapeutic alternative. Stimulation of the P6 Neiguan point, three fingers above the wrist on the palmar aspect of the forearm, has been shown to alleviate NVP by at least 50%. (P6 stimulation for 5 minutes four times daily, or as continuously as possible, may be administered by acupuncture, acupressure, manual pressure, Seabands, or possibly by a small TENS unit, Relief Band.) However, the small sample sizes and the failure of most trials to blind outcome assessment complicate interpretation of results. The acupuncture principles and practices for the treatment of nausea and vomiting using P6 and for the alleviation of pain also have been effectively and successfully extended to the treatment of postsurgical nausea and postsurgical pain relief.109 Because acupressure stimulation is safe and inexpensive as well as simple for women to achieve on their own at home with the use of wrist bands (e.g., Seabands), it is a reasonable part of a protocol for the treatment of NVP and hyperemesis. For nausea and vomiting, pressure is applied to the P6 point on the inside of the wrist, about 2 to 3 fingerbreadths proximal to the wrist crease, between the tendons, about 1 cm deep. Manually, the

When Is Hospitalization for NVP Recommended?

According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2004 “When a woman cannot tolerate liquids without vomiting and has not responded to outpatient management, hospitalization for evaluation and treatment is recommended. After the patient has been hospitalized on one occasion and a workup for other causes of severe vomiting has been undertaken, intravenous hydration, nutritional support, and modification of antiemetic therapy often can be accomplished at home. Nevertheless, the option of hospitalization for observation and further assessment should be preserved for patients who experience a change in vital signs or a change in affect or who continue to lose weight.”95

woman or someone else applies pressure for 5 minutes every 4 hours. Alternately, pressure can be applied by wearing an elasticized band with a 1-cm round plastic protruding button that is centered over the acupuncture point.107 The FDA has recently approved a wristband type, miniaturized, battery-operated transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulator designed to stimulate the P6 acupuncture site. Called the ReliefBand, it has been found to be helpful for mild to moderate nausea and vomiting but not for severe symptoms.106 It is available over the Internet for less than $100, and clients with nausea and vomiting of pregnancy may want to pursue this option.107

Hypnosis and Psychotherapy

A limited number of studies have demonstrated the efficacy of hypnosis in reducing NVP in some patients.110 Psychotherapy is more likely to be beneficial if anxiety is playing a role in the etiology of the condition.111 Because it is a safe intervention, and because many women become anxious, depressed, or isolated when dealing with protracted vomiting, some form of counseling is a reasonable part of a treatment plan if it can be afforded.

BOTANICAL TREATMENT OF NVP AND HYPEREMESIS GRAVIDARUM

According to Borrelli et al., the potential teratogenic effects of drugs administered during the critical embryogenic period of pregnancy drastically limit their use.112 Because of this, many pregnant women turn to complementary and alternative therapies including vitamins, herbal products, homeopathic preparation, acupressure, and acupuncture. 112 113 114 A recent literature survey reports that the most commonly used botanicals for the treatment of morning sickness are ginger, chamomile, peppermint, and raspberry leaf.115 Only ginger has been subjected to investigation of its safety and efficacy for NVP.

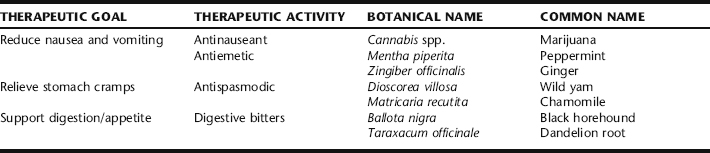

The botanical approach to treatment of NVP and Hyperemesis gravidarum, like conventional therapy, includes supportive, nonpharmacologic, and pharmacologic therapies, the latter in the form of antinauseant/antiemetic and antispasmodic herbs, and the use of gently herbs that support digestion (Table 13-3). The supportive and nonpharmacologic therapies used with herbal interventions are the same as those used with conventional therapies, and are described under Nonpharmacologic Treatment of NVP and Hyperemesis Gravidarum. NVP can be challenging to treat with consistent effectiveness in any individual woman, because it is difficult to find a single remedy that works consistently, especially over a prolonged time period. Typically, women find relief from a specific protocol for a short duration, only to find themselves nauseated by the remedy that helped in the first place. Therefore, it is preferable to have a “repertoire” or options a woman can try, and suggest she rotate these to create some variety and not become resistant to any single approach.

Ginger

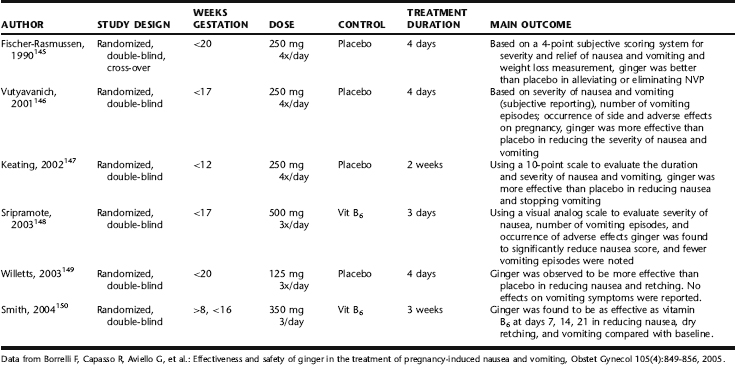

The best studied herb for NVP is Zingiber officinalis (Fig. 13-2). 145 146 147 148 149 150 A recent systematic literature search by Borrelli et al. identified six double-blind RCTs with a total of 675 participants and a prospective observational cohort study, which met the inclusion criteria for the review. The methodological quality of 4 of 5 of the RCTs was high according to the Jadad scale. The six studies are outlined in Table 13-4.

Four of the six RCTs (n = 246) showed superiority of ginger over placebo; the other two RCTs (n = 429) indicated that ginger was as effective as the reference drug (vitamin B6) in relieving the severity of nausea and vomiting episodes, including one study by Fischer-Rasmussen et al. that demonstrated efficacy and was superior to placebo for the treatment of hyperemesis gravidarum.116 The observational study and RCTs showed the absence of significant side effects or adverse effects on pregnancy outcomes. There were no spontaneous or case reports of adverse events during ginger treatment in pregnancy.112 The evidence, both scientific and traditional, is that ginger is safe and effective for some women with mild or moderate nausea and vomiting of pregnancy.107 It can be taken in the form of ginger ale, ginger tea sipped in small doses (to avoid nausea that may from drinking large amounts of any fluid), ginger capsules, or even candied ginger or spiced ginger cookies. It is generally recommended that women take on up to 1 g daily, as this is the largest amount that has been studied in clinical trials and been demonstrated as safe. Ginger ale must have real ginger in it, not just ginger flavoring, to be effective. The use of ginger is affordable and many women find this an acceptable approach, preferring to try this before resorting to conventional medications. The various routes of administration allow women to change how they are taking it regularly, which can help them avoid becoming sensitized to and nauseated from the ginger flavor. Occasionally, some women find the flavor unpleasant; adding peppermint leaf to the tea may improve the flavor for these women. Capsules allow women to avoid the smell and taste; however, some may find that eructation is unpleasant. As with all NVP remedies, there will be a great deal of individual variety determining what is palatable and tolerable.

Peppermint

Peppermint has a long history of use as a digestive aid, for improving digestion after meals, and calming nausea, flatulence, and abdominal spasms. The role of peppermint in the treatment of NVP has not been investigated; however, some benefit has been shown for the treatment of postoperative nausea, and also for the treatment of esophageal dysmotility, a physiologic finding that is also postulated as part of the etiology of NVP.76,151 Anecdotally, peppermint reportedly has a calmative effect on the stomach, in addition to reducing nausea, in women with NVP.142 It is taken as a tea in small sips (often combined with ginger for a pleasant-tasting tea), in the form of peppermint-flavored candies, or peppermint oil indirectly inhaled as aromatherapy. For the latter, many pregnant women have found it effective to douse a small piece of cotton wool with peppermint oil, and place this in a small glass vial that can be carried around in the pocket, opened and whiffed as needed, for example, during car travel.152 It is considered a safe and gentle remedy; however, peppermint herb is rich in volatile oils that can cross the placenta; thus, care should be taken to use only if necessary and in small amounts as a tea only, and not as a tincture or essential oil for ingestion. Neither the Botanical Safety Handbook, nor the German Commission E contradict the use of peppermint during pregnancy.153,154

Black Horehound

British trained herbalists commonly use black horehound in the treatment of motion sickness and NVP and with reports of great effects.116 The safety of this herb during pregnancy has not been evaluated. It is typically taken in small does (1 to 2 mL tincture three times/day), in combination with ginger, chamomile, or peppermint. It may also be added to a small amount of ginger ale or carbonated water (see dandelion root).

Wild Yam

Wild yam has been used in herbal medicine as an antispasmodic for not only the uterus and bladder, but for the stomach and intestines as well. The Eclectic physicians reported its use for the treatment of NVP, a use which has found its way into contemporary midwifery-botanical practice.152,155,156 Steroidal saponins in the plant may exert estrogenic effects by binding with endogenous estrogen receptors in the hypothalamus; however, this has only been demonstrated in vitro. There is no evidence to contraindicate the use of this herb during pregnancy, nor research on its safety or efficacy during pregnancy. There are no reports in the literature of wild yam having emmenagogic effects.143 It is typically taken in repeated doses of small amounts (e.g., 20 to 30 drops) in tincture form, sometimes combined dandelion root tincture (see the following) or added to ginger tea, when other remedies alone have failed.

Dandelion Root

Dandelion root is traditionally used as a gentle digestive bitter to improve digestion, increase bile flow choleretic, and relieve nausea and vomiting and improve appetite. The bitter constituents in dandelion increase bile flow, and act as an appetite stimulant.143,144 There are no reports in the literature of dandelion being either safe or contraindicated during pregnancy.143 Herbalist-midwives may recommend it taken alone in small doses (1 to 15 drops) as a tincture in water, or this same dose added to half a glass of ginger ale or lemon-flavored carbonated water. It has a mildly bitter taste, but dilute, is not typically offensive to pregnant women.

Cannabis

Cannabis (marijuana) has at least a 4000-year history of use as a medicinal plant, including extensive use for the treatment of gynecologic and obstetric conditions in many cultures throughout the world. 117 118 119 It was first described in Western medical literature by a physician in Ohio who used an extract of Cannabis indica to successfully remedy a near fatal case of hyperemesis gravidarum.120 Cannabinoids, delivered in the form of pharmaceutical preparations (e.g., nabilone and delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol) or directly smoked by the patient, are effective in reducing chemotherapy-induced nausea, vomiting, and anorexia, and may significantly improve appetite and ability to eat and drink. 121 122 123 124 125 It is used extensively by patients undergoing treatment for cancer and HIV, and may provide novel therapies for other GI disorders, including gastric ulcers, irritable bowel syndrome, Crohn’s disease, secretory diarrhea, paralytic ileus, and gastroesophageal reflux disease. 121 122 123 124 125 The 5-HT3–receptor antagonists, including cannabinoids, offer enhanced control of emesis while causing few side effects.126 Marijuana use may improve treatment adherence in patients undergoing treatments with protocol that have a high rate of side effects, such as HIV and cancer chemotherapy.127 Clinical trials that have looked at the efficacy of cannabis as an antiemetic have found it better than conventional antiemetics.128 Not only does cannabis reduce nausea and vomiting, but it has a significant effect on improving appetite and caloric intake.123, 129 130 131 Patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) symptoms report reductions in nausea, and improved ability to eat and drink, among improvement in other MS-related symptoms.132,133 In additional to its effects on central nervous system receptors, new research suggests the role of cannabinoids in the treatment of esophageal dysfunction, as one of its mechanisms of action.134 There are strong indications that cannabis is better tolerated than THC alone, because cannabis contains several additional cannabinoids, like cannabidiol (CBD), which antagonize the psychotropic actions of THC, but do not inhibit the appetite-stimulating effect.135

Cannabis is reported to be the most widely used recreational drug in pregnancy, with use during pregnancy in developed nations estimated to be approximately 10% to 20%.136,137 Not uncommonly, it is self-prescribed for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy.107,138 A recent (2003–2004) survey of 84 female users of medicinal cannabis, recruited through two compassion societies in British Columbia, Canada, found that of the 79 respondents who had experienced pregnancy, 51 (65%) reported using cannabis during their pregnancies. Although 59 (77%) of the respondents who had been pregnant had experienced nausea and/or vomiting of pregnancy, 40 (68%) had used cannabis to treat the condition, and of these respondents, 37 (over 92%) rated cannabis as “extremely effective” or “effective.”138 It is widely used by Rastafarian women in Jamaica and elsewhere to treat NVP, as well as other complaints, for example, labor pain.138 Because of its status as an illegal drug, as well as the general ethical issues that arise regarding conducting clinical studies during pregnancy, no formal clinical trials that examine the efficacy of this herb for use during pregnancy have been conducted.137,138 Because of its widespread use, its safety during pregnancy has been the subject of significant investigation; however, according to Westfall et al., it is important to be cognizant when evaluating marijuana and pregnancy safety data, that data derived from recreational use may not be equivalent to that which might be derived from therapeutic use, in terms of adverse effects.138 The influence of cannabis use during human pregnancy, and indeed, the medical use of marijuana generally, have been fraught with contradictions and controversies.137 A recent Medline database search by Karila et al. conducted for articles indexed from 1970 to 2005 using the terms cannabis/marijuana, pregnancy, fetal development, newborn, prenatal exposure, neurobehavioral deficits, cognitive deficits, executive functions, cannabinoids, and reproduction suggested that cannabis use during pregnancy is related to diverse neurobehavioral and cognitive outcomes, including symptoms of inattention, impulsivity, deficits in learning and memory, and a deficiency in aspects of executive functions.136 However, composite learning scores in these studies were not lower than controls, and adverse effects on learning were not significant when home factors were included.139 It is therefore difficult to ascribe direct effects on learning and behavior to maternal cannabis consumption during pregnancy.138 A report by Park et al. states that few studies have been conclusive regarding the effects of cannabis use during pregnancy. Cannabis use has been correlated with low birth weight, prematurity, intrauterine growth retardation, presence of congenital abnormalities, perinatal death, and delayed time to commencement of respiration. However, increased evidence of increased meconium staining was observed in newborns of heavy marijuana users who were from low-risk pregnancy and socioeconomic categories.137 Studies evaluating the use of cannabis during pregnancy have been confounded by the failure to separate the effects of alcohol versus marijuana on the newborn.136,140 A large survey (n = 12060) of British women showed no significant different in growth of the babies among women who did vs. did not use cannabis during pregnancy, based on self-report. Another large survey (n = 12885) of women in Copenhagen, which controlled for both alcohol and tobacco use, showed similar findings. A multisite study in the United States (n = 7470 women) showed no correlation between maternal cannabis intake and adverse pregnancy outcome including premature birth, low birth weight, or placental abruption. A study of Jamaican births (n = 9919) showed no correlation between maternal cannabis use and perinatal morbidity or mortality. Side effects of use reported in the HIV community and general population include more side effects, feeling high, sedation, euphoria, dizziness, dysphoria or depression, hallucinations, paranoia, and arterial hypotension.128 Chronic cannabis use has been reported to affect memory in patients using it to treat HIV chemotherapy-induced symptoms, and a study found that acutely, cannabis can impair driving response.125,141 Clearly, cannabis has effects on brain activity, cognition, perception, and function. Herbalists consider cannabis to be a reliable antiemetic, antinauseant, antianorexic, and analgesic. It is also considered to have mild oxytocic effects.142

NUTRITIONAL CONSIDERATIONS

See nonpharmacologic treatments.

Treatment Summary for NVP and Hyperemesis Gravidarum