Pre-hospital care

Introduction

Pre-hospital care is defined as care and treatment provided at the scene of an accident or acute and sudden illness in an ambulance, emergency vehicle or helicopter (Advanced Life Support Group 2011a, Ahl & Nystrom 2012). Historically, nurses have played an important role in the shaping of pre-hospital emergency care in the UK. The contribution of the hospital flying squad and the cardiac ambulance and the nurses working on them should not be underestimated. Not only did these teams provide a service that filled a therapeutic vacuum in patient care, but they were also instrumental in the development and evolution of these services. The work of both the flying squad and the cardiac ambulance significantly influenced the development of ambulance service and ultimately the birth of the paramedic.

Major incidents

It is neither essential nor desirable for all acute hospitals to be able to provide a mobile team in the event of a major incident. The responsibilities for ensuring mobile teams are available rests with the relevant regional or national health commissioning body. They may nominate those hospitals who will be responsible for deploying a Medical Emergency Response Incident Team (MERIT) to the scene of the incident, if requested to do so (DoH Emergency Preparedness Division 2005). In areas where active immediate care or British Association for Immediate Care (BASICS) schemes are operating, the relevant health board may nominate them to provide the on scene response rather than the acute hospitals. It is, however, essential that the emergency department staff are familiar with the local arrangements in their area.

Those hospitals that are identified as being able to provide a MERIT must ensure staff identified to deploy, the staff must understand the role they are to fulfil in the event of an incident, have the necessary competencies to fulfil that role and have received training to fulfil those competencies (DoH Emergency Preparedness Division 2005, 2007, Bland 2011).

Use and function of mobile teams

• supporting complex decision making – balancing the risks and benefits associated with at-scene clinical interventions

• supporting complex transport decisions – balancing the risks and benefits associated with pre-hospital triage, mode of transport and level of clinical escort

• provision of alternative forms of analgesic drugs and techniques

• provision of pre-hospital procedural sedation

• provision of pre-hospital emergency anaesthesia

• supporting the clinical use of critical care drugs and infusions, such as anaesthesia, vasoactive drugs and blood products

• use of complex monitoring and near patient investigation techniques, such as invasive haemodynamic monitoring and ultrasound.

In addition to the clinical skills required to provide added value to patient care, it is essential that team members have the skills that allow them to operate safely in the pre-hospital environment. They must be both safe and competent to work in environments that are inherently dangerous and where clinical conditions are suboptimal, such as poor lighting, confined spaces, and inclement weather. Additional specialist skills may also be necessary when working at incidents that involve potential hazardous materials.

Resourcing the team often results in the hospital being depleted of key, experienced personnel at a time when their expertise is in greatest demand. Plans must take this into account, ensuring that those required by the regional health board to provide a MERIT response are able to take action to ensure that a team can be assembled with appropriately skilled staff, when required to do so. The plan should not require action that would knowingly deplete essential services and expose the organization and patients to unacceptable risk.

The plan should also identify the equipment that is available to the MERIT, ensuring that it is appropriately packaged for clinical needs, operation and manual handling. The team must also have access to appropriate personal protective equipment, primarily for their safety but with due consideration to the identification of team members and key roles. Staff must therefore be familiar with the clinical and safety equipment they require and the safe and appropriate use of that equipment in the pre-hospital environment. Equipment should, as far as possible, be both compatible and interchangeable with the local ambulance service (Box 1.1).

Deployment of the team

Deployment of the team is often delayed, principally for logistical reasons, such as assembly of the team, collection of the equipment, and availability of transport for the team. Transport is a particular problem as most ambulances and their staff will be committed to patient care and transport and it may be some time before a vehicle is made available to transport the team. In the case of natural disasters, such as flooding or earthquakes, transport may be particularly badly affected due to road damage and loss of infrastructure (Dolan2011a, b, Dolan et al. 2011).

Triage for transport

Clinical prioritization and decision making may be assisted by the use of major incident triage algorithms. These algorithms vary from the conventional triage operated on a daily basis in the emergency department as they give a low priority for both treatment and transportation of those with critical injury, who will require large amounts of resource to care for them and are unlikely to survive. Where resources are plentiful these patients would be of a high priority, but in a major incident their priority is low, given that providing the required resources may deprive many others, with potentially survivable injuries, of care. This form of triage is often difficult for nurses and doctors to accept, but the aim is to do the greatest good for the greatest number (Barnes 2006).

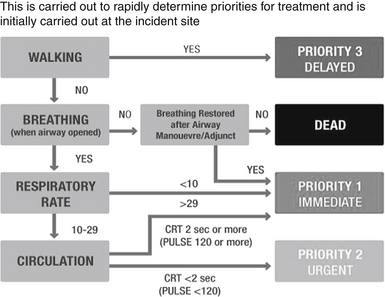

Triage for treatment usually follows the triage sieve approach (Life Support Group 2011a). This is a physiologically based system that considers the ability to walk, the patency of the airway, the respiratory rate and the capillary refill rate of pulse rate. The physiological parameters are appropriate for adults (Fig. 1.1). For children, the paediatric triage tape provides a suitable alternative with age-appropriate physiological parameters, whilst retaining the algorithm structure of the triage sieve (Wallis & Carley 2006).

Figure 1.1 Triage sieve. (After Hodgetts T, Cooke M, McNeill I (2002). The Pre-Hospital Emergency Management Master. London: BMJ Books.)

After initial treatment in situ and in the casualty clearing station, patients must be prioritized for transport to hospital. Triage for transport employs the triage sort system (Life Support Group 2011a), which is somewhat less crude than the triage sieve. The triage sort requires the measurement of the Glasgow Coma Scale, respiratory rate and systolic blood pressure (Fig. 1.1). Again this relates specifically to adult patients. For children the Paediatric Early Warning Score (PEWS) (Duncan et al. 2006) or Paediatric Advanced Warning Score (PAWS) (Advanced Life Support Group 2011b, Egdell et al. 2008) systems may be more appropriate.

Inter-hospital transfer

Emergency care practitioner

Over the past decade the role has evolved into that of the Emergency Care Practitioner (ECP); however, the title PEC was never really adopted. Despite a promising start the role of the ECP has not developed as quickly as many would have liked and the numbers of trained ECPs working in ambulance trusts is variable. However, despite some reservations and operational difficulties one interesting development appears to have endured, the employment of emergency nurses as ECPs alongside their paramedic-qualified ECP colleagues. Perhaps this should not be entirely surprising as the skills required in the assessment, treatment and discharge of patients with mainly minor injuries and illness is well established in the role of the Emergency Nurse Practitioner. There are, of course, new skills for emergency nurses working as ECPs to develop, some more obvious than others. For example, emergency nurses used to working in teams need to adapt to be comfortable working as a solo responder, without the range of equipment and patient testing available in the emergency department. Wound care including suturing, for example, has some added complexity in the patient’s home when compared with a treatment room in the emergency department.

References

Advanced Life Support Group. Major Incident Medical Management and Support: The Practical Approach at the Scene, third ed. London: BMJ Books; 2011.

Advanced Life Support Group. Advanced Paediatric Life Support: The Practical Approach, fifth ed. London: BMJ Books; 2011.

Ahl, C., Nystrom, M. To handle the unexpected: The meaning of caring in pre-hospital emergency care. International Emergency Nursing. 2012;20(1):33–41.

Barnes, J. Mobile medical teams: Do A&E nurses have the appropriate experience? Emergency Nurse. 2006;13(9):18–23.

Bland, S. Pre-hospital emergency care. In: Smith J., Greaves I., Porter K., eds. Oxford Desk Reference: Major Trauma. Oxford: Oxford Medical Publications, 2011.

Dolan, B. Rising from the ruins. Nursing Standard. 2011;25(28):22–23.

Dolan, B. Emergency nursing in an earthquake zone. Emergency Nurse. 2011;19(1):12–15.

Dolan, B., Esson, A., Grainger, P., et al. Earthquake disaster response in Christchurch, New Zealand. Journal of Emergency Nursing. 2011;37(5):506–509.

Duncan, H., Hutchison, J., Parshuram, C.S. The Pediatric Early Warning System score: A severity of illness score to predict urgent medical need in hospitalized children. Journal of Critical Care 09. 2006;21(3):271–278.

Egdell, P., Finlay, L., Pedley, D.K. The PAWS score: Validation of an early warning scoring system for the initial assessment of children in the emergency department. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2008;25(11):745–749.

Hodgetts, T., Cooke, M., McNeil, T., The Pre-Hospital Emergency Management Master, London, BMJ Books, 2002.

Wallis, L.A., Carley, S. Validation of the paediatric triage tape. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2006;23:47–50.