Chapter 13 Posterior Mini-Incision Hamstring Harvest Approach for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction*

Overview

Hamstring (HS) use for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR) has increased greatly in the past 5 years as improved fixation techniques have allowed stability rates to meet or exceed those of bone–patellar tendon–bone (BPTB) grafts.1 It has been said that the harvest is the most difficult part of HS ACLR2 and may require a learning curve of roughly 50 procedures.3

Anatomy

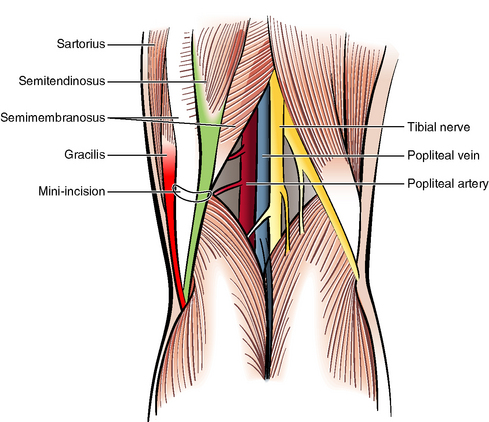

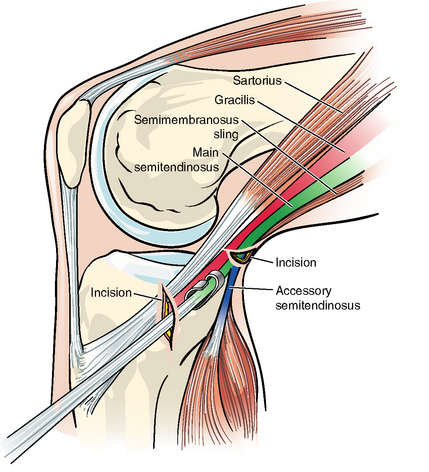

The accessory ST tendon is the primary structure leading to premature amputation of the ST tendon after tendon harvesting. This structure is not described in any standard anatomy texts. However, several papers have described it.4–6 It is present in about 70% of patients. Other cross-connections exist variably from the ST and Gr tendons. In some patients they are thin and will be easily cut with a tendon stripper. However, the accessory ST in particular can be almost as thick as the main trunk of the ST. Especially in these cases, the tendon stripper can easily sever the main trunk of the ST, rendering it too short to use. The variability of the anatomy is such that it is difficult to devise a consistent plan for freeing the tendon using the traditional approach, except to run a scissors along both sides of both tendons. Branches of the saphenous nerve, and indeed its main trunk, are very close by, and saphenous neurapraxia is very common after these dissections. The takeoff of the accessory ST was shown in our studies to be an average of 5 to 6 cm posterior to the tibial crest. Although orthopaedic surgeons rarely operate posteriorly and may be apprehensive about a posterior approach, the posterior approach does not subject neurovascular structures to significant risk. Our cadaver studies showed that the closest neurovascular structure was the popliteal artery, but in eight specimens it was always at least 2.9 cm away from the ST tendon. It was also shielded from the ST tendon by the semimembranosus muscle.

Surgical Technique

Making the Posterior Skin Incision

The ST is the most prominent tendinous structure in the popliteal fossa and runs just medially to the midline. The affected lower extremity is externally rotated, and the knee is flexed about 30 degrees. The surgeon bends over the leg to see posteromedially. The incision should be made directly over it in the popliteal fossa, shading slightly anteromedially (Fig. 13-1). If the ST cannot be felt, the incision can be put into the soft spot in the skin just medial to the midline. The location of this incision is not critical because the tendon can always be found by moving the highly mobile skin in this area. The incision should be made 3 cm in length initially but need only be 2 cm in length once experience is gained. It should be put within or parallel to a skin crease. After the dermis is incised with a #15 blade, the subcutaneous tissue is opened by spreading with Metzenbaum scissors.

Finding the Semitendinosus

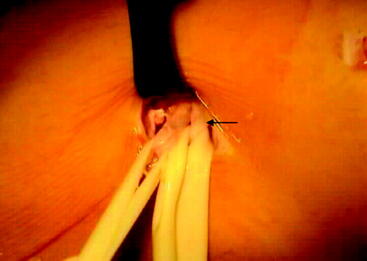

An index finger should probe the incision, fishing the tendon out bluntly. If it is not easily found in this manner, two Senne retractors can be used to open the incision, and the tendon can be found under direct visualization. Once the tendon is identified, a right-angle clamp is passed around it. A ¼-inch Penrose drain then captures it and is loosely clamped (Fig. 13-2).

Identifying the Semitendinosus in the Anterior Incision

A right-angle clamp is inserted in the anterior incision and passed around the ST tendon to grasp a ¼-inch Penrose drain (Fig. 13-3). The surgeon’s other index finger is still under the tendon and guides the clamp. The surgeon may insert the short end of an Army-Navy retractor and identify the tendon by direct visualization. A ¼-inch Penrose is then passed around the tendon and clamped with a right angle.

Identifying the Gracilis

Using the ST as a guide, the Gr can be found either in the posterior or anterior incision (Fig. 13-4) either before or after the ST is stripped proximally. If the ST is 30 cm or longer, we do not harvest the Gr but rather use a four-strand ST graft.

Harvesting the Semitendinosus and Sectioning the Accessory Semitendinosus

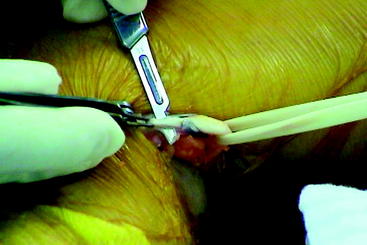

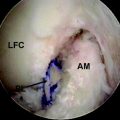

A small, closed corkscrew tendon stripper is passed around the ST near its common insertion with the Gr without disrupting it. It is gently but firmly passed proximally with a firm rotary, back-and-forth motion. Resistance will be felt when the stripper encounters the accessory ST (Fig. 13-5). At this point the stripper should be carefully advanced another 1 or 2 cm, taking care not to apply excessive force. Two Senne rakes are then placed in the posterior incision, and the mobile skin is moved anteriorly over the head and neck of the tendon stripper to expose them while maintaining firm pressure on the stripper. The surgeon uses a forceps and Metz scissors to dissect the filmy tissue off the stripper neck. Sitting directly on the neck of the tendon stripper will be the accessory ST, with the main trunk of the tendon extending outward from the corkscrew (Fig. 13-6). This accessory ST should be cut with either a Metz scissors or a #15 blade. The stripper will now slide freely toward the proximal. It should be pushed until the tendon is freed proximally while countertension is maintained with a ¼-inch Penrose or index finger near its insertion. Once freed, the ST is delivered out the anterior incision.

Freeing the Tendon Distally

With the two (or one) tendons delivered out the anterior incision, the periosteum is scored parallel and to the deep side of the tendon(s) (Fig. 13-7). An additional 2 cm of periosteum can then be harvested in line with the insertion, essentially prolonging it with tough tissue that also has the benefit of the growth factors found on its cambium layer for intratunnel fixation and ingrowth.

Graft Preparation

The tendon(s) is given to the assistant at the back table for cleaning and measuring.

Harvest Problems with the Traditional Approach and Solutions Using the Combined Posterior/Anterior Mini-Incision Approach

Problem 3: Hang-Up of the Tendon Stripper in the Distal Thigh at the Fanning-Out of the Semitendinosus or Semimembranosus Sling

Problem 4: Saphenous Nerve Trauma and Numbness

Numbness has been shown to occur in more than half of patients after ACL surgery.7,8 Most of the time it is not significantly bothersome to the patient. However, it is bothersome to occasional patients. In addition, there is evidence that stiffness and complex regional pain syndrome (formerly reflex sympathetic dystrophy) are more common with significant nerve trauma after knee surgery.

Problem 5: Cosmesis

Cosmesis is not generally a significant problem, but our studies have shown4 that cosmesis does matter to many patients, especially to females.

Who Should Use this Technique?

This technique is particularly desirable for the new or occasional HS harvester and has proven valuable to those in training programs. However, it will also facilitate the harvest and improve cosmesis for most experienced HS surgeons who now use the traditional approach—as it did for the author, who began to use it after fellowship training in hamstring ACLR and 6 years of practice performing the standard technique. Initially the incisions can be made larger. Cosmesis will still be better than with the traditional approach. The incisions can be reduced with experience if the surgeon wishes. 4HS grafts have now been shown to have excellent stability rates1 (see Chapter 69), and the harvest has been shown to be the chief obstacle to use of the technique. With this approach the surgeon can accomplish the harvest safely and reliably so that harvesting is no longer a significant factor in graft choice.

1 Prodromos CC, Joyce BT, Shi KS, et al. A meta-analysis of stability after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction as a function of hamstring versus patellar tendon graft and fixation type. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:1202-1208.

2 Williams RJIII, Hyman J, Petrigliano F, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with a four-strand hamstring tendon autograft. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86A:225-232.

3 Howell SM. Principles of hamstring fixation. ACL reconstruction: from graft choices and fixation to single and dual tunnel techniques. Instruction course presented at the meeting of the Arthroscopy Association of North America, Vancouver, BC, Canada. May 2005.

4 Prodromos CC, Han YS, Keller BL, et al. Posterior mini-incision technique for hamstring anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction graft harvest. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:130-137.

5 Ferrari JD, Ferrari DA. The semitendinosus: anatomic considerations in tendon harvesting. Orthop Rev. 1991;20:1085-1088.

6 Pagnani MJ, Warner JJ, O’Brien SJ, et al. Anatomic considerations in harvesting the semitendinosus and gracilis tendons and a technique of harvest. Am J Sports Med. 1993;21:565-571.

7 Portland GH, Martin D, Keene G, et al. Injury to the infrapatellar branch of the saphenous nerve in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: comparison of horizontal versus vertical harvest site incisions. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:281-285.

8 Spicer DDM, Blagg SE, Unwin AJ, et al. Anterior knee symptoms after four-strand hamstring tendon anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2000;8:286-289.