29 Postanesthesia care complications

Acute Myocardial Infarction: Occurs when an area of heart muscle dies or is permanently damaged because of an inadequate supply of oxygen to that area.

Anaphylactic Reactions: Anaphylaxis is a severe whole-body allergic reaction that occurs rapidly and causes a life-threatening response that involves the whole body.

Aspiration: The inhalation of either oropharyngeal or gastric contents into the lungs.

Awareness During Anesthesia: Occurs when a person is aware of some portion of the procedure (sometimes even pain) during general anesthesia; can cause long-term psychologic effects and symptoms of posttraumatic stress.

Bradycardia: A heart rate of less than 60 beats/min (adult) with a regular rhythm and P waves present.

Bronchospasm: Narrowing of the bronchi and bronchioles from smooth muscle contraction that results in wheezing, coughing, and decreased oxygen exchange.

Delayed Emergence (Awakening): Patient emergence from anesthesia is delayed; failure to emerge can be classified as the result of drug effects, metabolic disorders, or neurologic disorders.

Dilutional Hyponatremia: Absorption of irrigating solutions through open blood vessels (during prostate resection) or perforation of the uterine or bladder wall that leads to circulatory overload from water intoxication. May also be caused by excessive free water intake, excess sodium losses, or inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion.

Emergence Excitement: A condition characterized by restlessness, disorientation, crying, moaning, irrational talking, and inappropriate behavior.

Hemolytic Transfusion Reactions: An ABO-incompatible blood reaction that precipitates a hemolytic reaction that results in agglutination, or clumping, of red blood cells, which blocks the patient’s capillaries and thus obstructs the flow of blood and oxygen to vital organs.

Hemorrhage: Rapid, copious blood loss.

Hypertension: A blood pressure increased 20% to 30% above the baseline blood pressure.

Hyperthermia: A core temperature of more than 38° C.

Hypotension: A blood pressure that is less than 20% to 30% of the baseline blood pressure.

Hypothermia: A core temperature of less than 36° C.

Hypoventilation: A decrease in respiratory rate and tidal volume that leads to an increase in partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2).

Hypoxemia: A PaO2 of less than 60 mm Hg.

Laryngospasm: An involuntary partial or complete closure of the vocal cords, caused by secretions, or stimulation or irritation of the laryngeal reflexes during emergence.

Malignant Hyperthermia (MH): A pharmacogenetic (autosomal dominant inheritance) disorder of muscle metabolism involving hypermetabolism that can be triggered by succinylcholine or the volatile anesthetics.

Noncardiogenic Pulmonary Edema: Respiratory disorder that most commonly occurs after an obstructive event that results in pulmonary capillary leakage and pulmonary edema.

Nonhemolytic Febrile Reactions: Most often caused by sensitivity to leukocytes and platelets and seen most often in patients who have received multiple transfusions.

Perforated Viscus: Internal organs perforated during the operative procedure.

Plasma Cholinesterase Deficiency: An uncommon genetic disorder that renders the patient with an inability to metabolize succinylcholine, resulting in prolonged skeletal muscle paralysis and apnea of 2 hours or more.

Pneumothorax: An accumulation of air or gas in the pleural space.

Postdischarge Nausea and Vomiting (PDNV): Nausea or vomiting that occurs after discharge from the health care facility after ambulatory surgery.

Postdural Puncture Headache: A headache that typically develops 24 to 48 hours after lumbar puncture from a spinal needle placement or unintentional dural puncture during an epidural placement.

Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting (PONV): Nausea or vomiting that occurs within the first 24 hours after inpatient surgery.

Pulmonary Edema: Increase in lung fluid as a result of leakage from pulmonary capillaries into the interstitium and alveoli of the lung; leads to impaired gas exchange and may cause respiratory failure.

Pulmonary Embolism: A sudden blockage of an artery in the lungs by fat, air, clumped tumor cells, or a blood clot; usually a blood clot that traveled to the lung from the leg.

Spinal Epidural Hematoma: A hematoma after spinal procedures or surgery; blood accumulates between the spinal dura and bone compressing nerves; without prompt treatment, it can cause permanent neurologic deficits.

Tachycardia: A heart rate greater than 100 beats/min (adult) with a regular rhythm and P waves present.

Transfusion-Related Acute Lung Injury (TRALI): Rare but devastating complication of blood component therapy; findings are similar to adult respiratory distress syndrome and consist of hypotension, fever, dyspnea, and tachycardia.

Respiratory complications

Airway management and respiratory care are first in the mind of the perianesthesia nurse when patients arrive in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU). Avoidance of postoperative pulmonary complications, including atelectasis, pneumonia, respiratory failure, and exacerbation, helps to reduce patient morbidity and mortality rates. The perianesthesia nurse works to prevent these serious longer-term complications by maintaining and improving the patient’s respiratory function in the immediate postanesthesia period of care. Some patients are at greater risk for developing these complications. Primarily these risk factors are related to the patient or the procedure. Box 29-1 lists the most common risk factors supported by evidence.1

BOX 29-1 Risk Factors for Postoperative Pulmonary Complications

Data from Smetana GW, et al: Preoperative pulmonary risk stratification for noncardiothoracic surgery: systematic review for the American College of Physicians, Ann Intern Med 144:581–595, 2006.

Laryngospasm

Laryngospasm is an involuntary partial or complete closure of the vocal cords, caused by secretions or stimulation or irritation of the laryngeal reflexes during emergence. Wheezing, reduced compliance, stridor (partial), paradoxical chest or abdominal movements, and absence of ventilation (complete) are signs and symptoms of laryngospasm. Ventilation is decreased or absent, and oxygenation of the patient is difficult as carbon dioxide builds (PaCO2 increases). Treatment includes airway maneuvers (chin lift/jaw thrust), elevation of the head of bed to maximize respiratory excursion, and application of a bag-valve-mask for continuous positive pressure with oxygen. Secretions need to be carefully removed with suction. The patient may need reintubation to secure the airway if mask ventilation is difficult. Medications include succinylcholine and can include other neuromuscular blocking agents and lidocaine. When the patient has received a neuromuscular blocking agent, the patient may need sedation to reduce anxiety related to apnea, muscle relaxation, and awareness.

Aspiration

Identified as a high-risk low-frequency occurrence, aspiration may be observed in the postanesthesia setting. The patient with a nasal or oropharyngeal airway in place and returning gag reflexes may become nauseated and vomit. In a nonresponsive state and supine position, the patient is at greater risk for aspiration. Types of aspirates include large particle, clear acidic or nonacidic fluid, foodstuff or small particle, and contaminated material. In addition, foreign bodies such as teeth or blood may be aspirated. Symptoms include unexplained tachypnea and tachycardia, cough, bronchospasm, hypoxemia, atelectasis, interstitial edema, hemorrhage, and acute respiratory distress syndrome. The aspiration can trigger laryngospasm, infection, and pulmonary edema. Prevention of aspiration is preferred. Patients at risk should be identified before surgery and premedicated. Patients at risk are patients with emergent procedures, known full stomachs, or history of gastroesophageal reflux disease; those older than age 65 years; and women in labor. Medications include histamine blockers, nonparticulate antacids, and anticholinergic agents. During surgery, rapid sequence induction and nasogastric tube placement may help to minimize the risk of aspiration. After surgery, maintenance of the endotracheal tube until airway reflexes have returned and positioning of the patient with the head to the side or in a left lateral decubitus position can aid in decreasing the risk of aspiration. If aspiration occurs, hypoxemia should be corrected and hemodynamic stability maintained. The patient may need reintubation and suctioning and mechanical ventilation. Arterial blood gases assist in planning respiratory management of the patient. A chest radiograph is obtained, but findings may be inconclusive initially; radiographic findings may lag behind clinical signs by 24 hours after the suspected aspiration event. Prophylactic antibiotics or steroids are not recommended. Tracheal secretions should be cultured; if results are positive, antibiotics can be prescribed.

Noncardiogenic pulmonary edema

Noncardiogenic pulmonary edema may be the result of upper airway obstruction, laryngospasm, bolus dosing with naloxone, incomplete reversal of neuromuscular blockade, or a significant period of hypoxia. When the cause is obstructive in origin, two types of postobstructive pulmonary edema (POPE) have been identified: type I and type II.2 Both are present with acute respiratory distress. Type I usually occurs within 60 minutes of a precipitating event, but onset can be delayed up to 6 hours. Type I POPE may follow postextubation laryngospasm, epiglottitis, croup, choking or foreign body, strangulation, hanging, endotracheal tube obstruction, laryngeal tumor, goiter, mononucleosis, postoperative vocal cord paralysis, migration of the urinary catheter balloon used for tamponade epistaxis, near drowning, and intraoperative direct suctioning of an endotracheal tube adapter.3 Type II POPE develops soon after relief of chronic upper airway obstruction, such as after tonsillectomy or adenoidectomy, removal of upper airway tumor, choanal stenosis, and hypertrophic redundant uvula.3

Signs and symptoms include hypoxemia, cough, failure to maintain oxygen saturation levels, tachypnea, and frothy sputum. Treatment includes supplemental oxygen administration and maintenance of a patent upper airway. CPAP may be used. Patients with an inability to maintain a patent airway may need intubation and mechanical ventilation with PEEP. For patients with significant compromise, hemodynamic support and continued observation in an intensive care unit may be needed. Patients with noncardiogenic pulmonary edema typically recover rapidly after the intense initial phase and leave the critical care unit within approximately 24 to 36 hours and without permanent sequelae from the event.

Pulmonary embolism

Patients predisposed to development of pulmonary emboli include patients who are obese or immobile, who are undergoing pelvic or long bone procedures, and who have a history of congestive heart failure or malignant disease.4 Signs and symptoms can include tachypnea, pleuritic chest pain, hemoptysis, breathlessness, and a sense of impending doom. Treatment is supportive for correction of hypoxemia and hemodynamic instability. Intravenous heparin and morphine sulfate can be given to help stabilize the pulmonary capillary membrane. Prevention of venous thromboembolism and subsequent pulmonary emboli development includes subcutaneous unfractionated heparin, low–molecular-weight heparins, or intermittent or sequential compression devices.

Cardiovascular complications

Major cardiovascular perioperative risks are identified as myocardial infarction, heart failure, and death. Clinical predictors of increased perioperative cardiovascular complications are listed in Box 29-2.5

BOX 29-2 Clinical Predictors of Increased Perioperative Cardiovascular Complications

Active cardiac conditions—major (delay or cancel surgery unless emergent)

Data from Fleisher LA, et al: 2009 ACCF/AHA focused update on perioperative beta blockade incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and care for noncardiac surgery, J Am Coll Cardiol 54(22):e13–e118, 2009.

Tachycardia

Sinus tachycardia occurs commonly in the postanesthesia setting. Causes include hypoxia, hypercarbia, hypovolemia, sepsis, hyperthermia, heart failure, pain, drugs, and psychologic stress. Treatment includes administration of supplemental oxygen, ventilation support, and evaluation of fluid and cardiac status. If the condition results from pain, medication with analgesics is the treatment. Sedatives may be needed if the condition is from anxiety or stress. If the patient is hyperthermic, the patient’s core temperature is lowered with recommended cooling devices. Tachycardia in patients with coronary artery disease can increase the risk of myocardial ischemia.

Hypotension

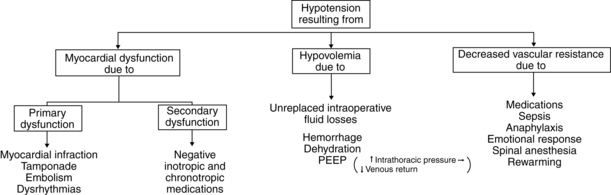

Hypotension is defined as blood pressure that is less than 20% to 30% of the baseline blood pressure.6 Causes range from use of an inappropriately sized cuff, to hypovolemia, myocardial dysfunction, and a decrease in systemic vascular resistance (Fig. 29-1). Management and treatment of hypotension in the PACU includes use of a cuff of the appropriate size, administration of supplemental oxygen, initiation of fluid resuscitation, stoppage of drug infusions if causative, and elevation of the legs. Inotropic agents or vasopressor or vasoconstrictive agents may be ordered.

Hypertension

Hypertension is defined “as persistent elevation of systolic blood pressure greater than 140 mm Hg or a diastolic blood pressure greater than 90 mm Hg or requires an antihypertensive treatment.”7 Too small or narrow of a cuff can result in abnormally elevated blood pressures. Pain, stress, hypoxemia, hypercarbia, fluid overload, delirium, drugs, bladder, bowel or stomach distention, or hypothermia can cause hypertension. Many of the patients in PACU in whom hypertension develops have preexisting hypertension. The elevation in blood pressure is usually benign and short lived; however, the hypertension can precipitate myocardial ischemia in the patient with coronary artery disease as a result of stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system. Treatment for hypertension includes use of an appropriately sized cuff and identification and management of the underlying cause first. This condition may necessitate ventilatory support and oxygen administration, analgesics or sedatives, bladder decompression, and antihypertensive agents.

Patients who have had a cervical or thoracic spinal cord injury (above T6) are at risk for developing autonomic dysreflexia, which is a massive uninhibited sympathetic cardiovascular response to noxious stimuli (e.g., bowel or bladder overdistention) characterized by paroxysmal hypertension, pounding headache, facial flushing, sweating, temporal or neck vessel engorgement, nasal congestion, blurred vision, chill bumps, chills, nausea, and occasional bradycardia. Treatment includes elimination of the precipitating stimuli if known and elevation of the head of bed. Pharmacologic treatment may be needed to reduce the blood pressure if the blood pressure remains elevated after these measures. Medications for the treatment of hypertension include nifedipine, nitrates, captopril, prazosin, phenoxybenzamine hydrochloride, prostaglandin E2, and sildenafil.8

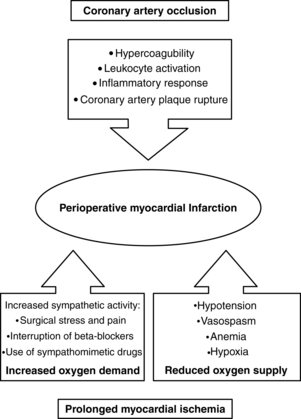

Acute myocardial infarction

The patient with a history of preexisting coronary artery disease, diabetes, and significant dysrhythmias is at risk for perioperative cardiac events (see Box 29-2). The pathology of perioperative myocardial infarction is shown in Fig. 29-2.9

FIG. 29-2 Pathology of perioperative myocardial infarction.

(From Kertai MD, et al: Predicting perioperative cardiac risk, Progress Cardiovasc Dis 47(4):240–257, 2005.)

When a patient has chest pain in the PACU, the cause needs to be evaluated, with the first consideration for the source as cardiac in origin (Box 29-3). The signs and symptoms of myocardial infarction include chest pain, tachypnea, tachycardia or other dysrhythmias, hypotension or hypertension, pallor, diaphoresis, cool extremities, nausea, vomiting, and generalized weakness. New Q waves or increasing prominence of existing ones, ST segment elevations, and T wave inversions may be seen on electrocardiogram (ECG) results. Initial treatment is aimed at relieving chest pain, reducing cardiac workload, stabilizing cardiac rhythm, limiting infarct size, preventing further damage, and detecting and treating complications. The first response is to order a 12-lead ECG; initiate supplemental oxygen to maintain arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2) above 90%10; administer morphine, nitrates, and antiplatelet or anticoagulant agents; and continuously monitor the ECG. Laboratory blood studies are obtained, including troponin-I, troponin-T, MB fraction of creatine kinase (CK-MB), and CK-MB isoforms. The patient is evaluated and transferred to a critical care unit as indicated by diagnosis for continued monitoring and possible interventional procedures and management.

BOX 29-3 Differential Diagnosis of Chest Pain

Data from Anderson JL, et al: 2011 ACCF/AHA focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-st-elevation myocardial infarction, Circulation 123:e426–e579, 2011; Klingensmith ME, Washington University Department of Surgery in St. Louis: The Washington manual of surgery, ed 6, Philadelphia, 2011, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Ruskin K, Rosenbaum SH: Anesthesia emergencies, New York, 2011, Oxford University Press.

Thermoregulation

For a more detailed discussion of thermoregulation, see Chapter 53.

Hypothermia

Hypothermia is defined as a core temperature of less than 36° C.11 Signs and symptoms of hypothermia include shivering, restlessness, discomfort, and cold pale cyanotic extremities and distal appendages from peripheral vasoconstriction. This state can lead to delayed drug clearance, myocardial ischemia, unexplained hypertension, and residual paralysis from neuromuscular blocking agents. The American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline for the Promotion of Perioperative Normothermia offers the perianesthesia nurse guidance for assessment and management of the patient who is hypothermic during the perianesthesia period.11 Recommendations for treatment of the patient include active rewarming, supplemental oxygen administration, and ventilatory support if necessary.

Hyperthermia

Hyperthermia is defined as a core temperature of more than 38° C.11 Temperature elevations may be the result of blood transfusion reactions, warm environment, drug-induced fever, use of anticholinergic drugs, overcorrected hypothermia, endocrine disorder, hypothalamic injury, or malignant hyperthermia (MH). Signs and symptoms include fever, tachycardia, and warm flushed skin and other sign and symptoms depending on the cause of the hyperthermia (shaking, chills or rigors, agitation). The cause should be identified and corrected when possible. Cooling blankets or pads may be used, and an antipyretic agent may be given.

Anesthesia-related complications

Awareness under anesthesia

When patients arrive in the postanesthesia care unit, nurses tell the patients that surgery is over, they are in the PACU or wake-up room, they are doing well, and the nurses are going to take care of them while they are awakening. This reassurance can minimize fears of waking up while still in the operating suite. Frequent reminders to the patients of status and safety help reduce anxiety related to awareness or awakening. If a patient indicates recall of events from the operating suite, the perianesthesia nurse should contact the anesthesia care provider to come to the bedside and interview the patient. Telling the patient an event did not occur or was a dream is inappropriate. If an awareness event is suspected, the nurse should sympathize and apologize to the patient, explain and answer questions as appropriate, and notify the anesthesia care provider, surgeon, and risk management department.

Anesthesia care providers, when interviewing patients after procedures, may use a structured interview tool, such as the Brice questionnaire (Box 29-4).12 This interview may dispel concerns and identify awareness events with greater frequency.

BOX 29-4 Original Brice Questionnaire

1. What was the last thing you remember before you went to sleep for your operation?

2. What was the first thing you remember after your operation?

3. Can you remember anything in between those two periods?

From Brice DD, et al: A simple study of awareness and dreaming during anesthesia, Br J Anaesth 42:535–542, 1970.

Emergence excitement

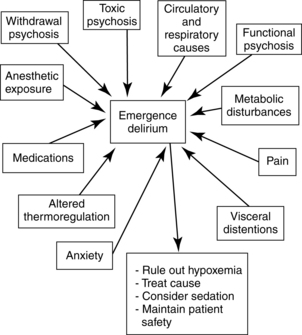

Most patients emerge from general anesthesia in a calm tranquil manner. Some patients, however, emerge in a state of excitement, a condition characterized by restlessness, disorientation, crying, moaning, irrational talking, and inappropriate behavior. In the extreme form of excitement, which is also called emergence delirium (Fig. 29-3) or agitation, the patient screams, shouts, and wildly thrashes. Postoperative delirium or emergence excitement is defined as responsive or unresponsive agitation.

FIG. 29-3 Emergence delirium in the postanesthesia care unit: contributing factors and treatment.

(From Nagelhout JJ, Plaus KL: Nurse anesthesia, ed 4, St. Louis, 2010, Saunders.)

The restless patient needs constant careful observation. Gentle physical restraint may be necessary for prevention of injury. Several nurses or attendants may be needed to provide safety for the patient, and for the caregivers too. Treatment is symptomatic. If hypoxia, pain, and full bladder are ruled out, a change in position may have a quieting effect. Physostigmine can be used to reverse central anticholinergic drug effects. Anxiolytics, such as midazolam, usually calm the patient. If sedative treatment is instituted, the patient should be monitored for respiratory depression. Nurses should be alert to increased agitation after benzodiazepine administration. These agents may contribute to restlessness rather than decreasing it; a paradoxical reaction to benzodiazepines can occur.

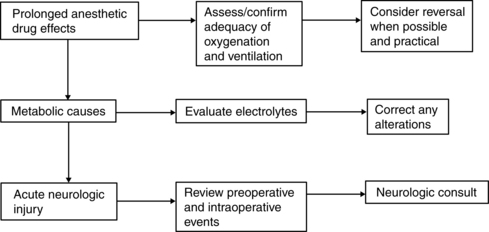

Delayed emergence (awakening)

Occasionally patients awaken from anesthesia more slowly than expected. Causes include prolonged action of anesthetic and other drugs; metabolic problems such as hypoglycemia, hypocalcemia, hyponatremia, and hypermagnesemia; hypovolemia; hypothermia; and neurologic injury. Respiratory inadequacy with resultant hypercarbia and hypoxemia can result from opioids, sedatives, other anesthetic agents and adjuncts, or neurologic causes. The most common cause of delayed awakening is prolonged drug effects (Fig. 29-4).

FIG. 29-4 Delayed emergence (awakening).

(From Litwack K: Postanesthesia care nursing, ed 2, St. Louis, 1995, Mosby.)

Evaluation of the patient for possible cerebrovascular accident (stroke) should be included in the immediate assessment of the postanesthesia patient. Observe facial symmetry assessing for droop, evaluate speech assessing for slurring of words and abnormal speech, and assess arm drift. In addition, neurologic assessment including level of orientation, pupillary response, movement, and muscle strength can assist in determining variations and need for intervention to avoid further neurologic deterioration.

Nausea and vomiting

Mechanism of action

The vomiting (emetic) center is located in the medulla near the dorsal nucleus of the vagus nerve. It can be excited by reflex impulses that arise in the pharynx, stomach, or other portions of the gastrointestinal tract. Foreign materials, such as blood and mucus or irritant gases in the stomach or other portions of the gastrointestinal tract, can produce nausea and subsequent vomiting. The vomiting center can be excited by impulses received from cerebral centers, because the vomiting center is located close to the fourth cerebral ventricle (see Chapter 10) and receives impulses from the chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ), cerebral cortex, and vestibular center. Of these physiologic centers, the CTZ has the greatest effect on the vomiting center. In fact, when stimulated by the appropriate stimuli, the CTZ can initiate vomiting independent of the vomiting center. The CTZ is rich in serotonin, dopamine, histamine, and opioids and is not protected by the blood-brain barrier. This lack of protection allows the CTZ to be directly stimulated by chemical stimuli from the systemic circulation or the cerebral spinal fluid.

Incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting

Primary risk factors for postoperative nausea and vomiting fall into three categories: patient-specific, anesthetic-related, and surgery-related.13 Patient-specific risk factors include female gender, nonsmoking status, history of PONV, and history of motion sickness. Use of volatile anesthetics, nitrous oxide, and postoperative opioids are the anesthetic-related factors. Duration of surgery and anesthesia and the type of surgery are the surgery-related factors.

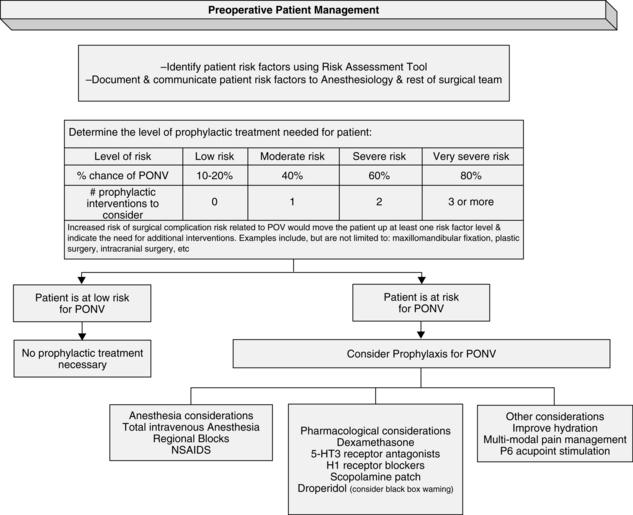

The presence of each additional factor predicts increased risk of development of PONV and guides antiemetic prophylaxis for the prevention of PONV. Patients with zero to one factor have a low level risk of PONV; those with two are at moderate risk, with an approximately 40% chance of PONV. With three or more factors, patients have a 60% chance of development of PONV. Very severe risk, a more than 80% risk of PONV, can be found in patients with four to five risk factors. See Fig. 29-5 for recommendations for preoperative antiemetic prophylaxis from the American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline for the Prevention and/or Management of PONV/PDNV.14

Care of the patient with nausea and vomiting

In most cases, vomiting is preceded by nausea. Nausea is a feeling of impending vomiting. Several signs accompany the feelings of nausea. The patient usually has excessive salivation, dilated pupils, tachypnea, swallowing, pallor, sweating, and tachycardia. If the patient’s nausea worsens, retching usually occurs and the tachycardia may change to bradycardia. If patients have nausea, they should be encouraged to breathe deeply. A cool washcloth placed on the patient’s forehead and words of encouragement sometimes help to ease the nausea. The nurse remains with the patient because the patient may begin vomiting without notice, and the danger of aspiration of vomitus and an obstructed airway is always present.

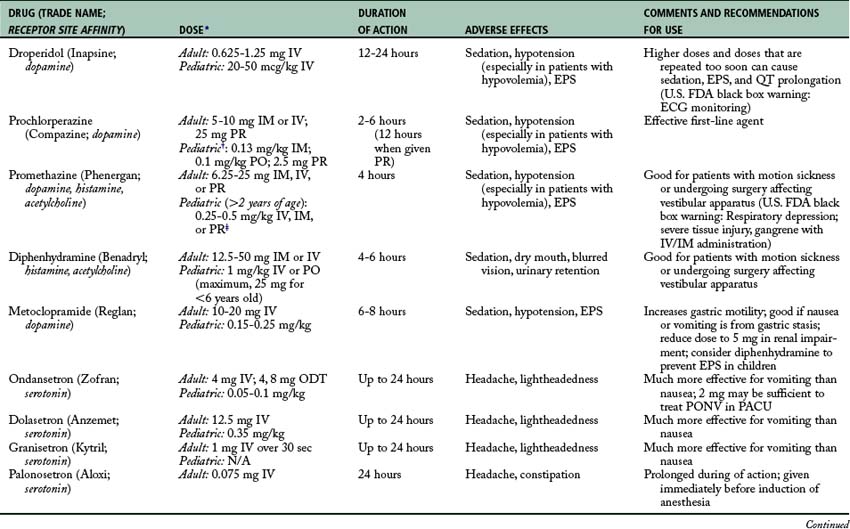

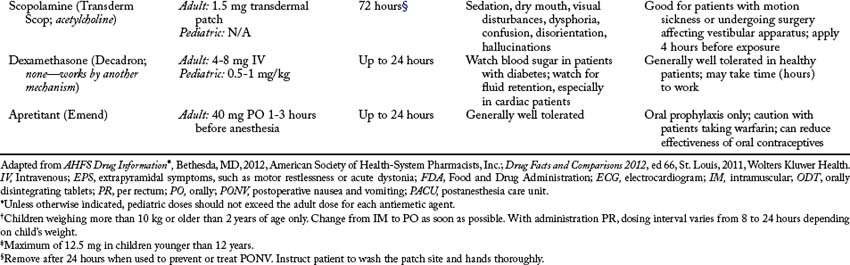

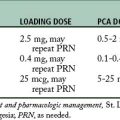

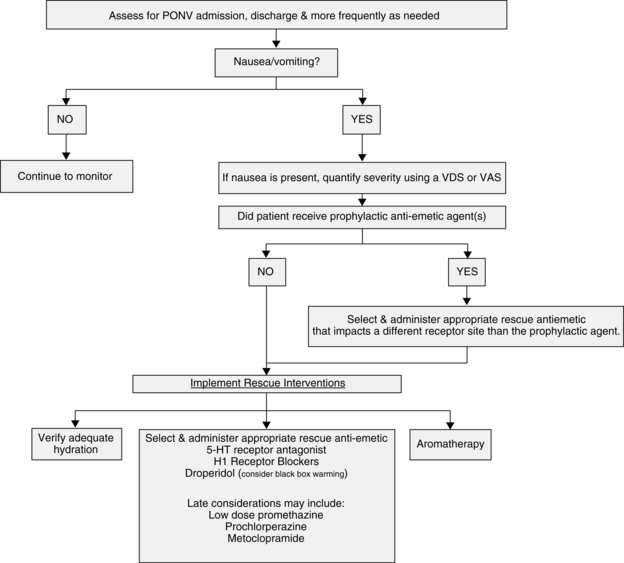

Pharmacologic interventions

If the previous intervention does not relieve the nausea and vomiting, a pharmacologic intervention is needed (Fig. 29-6; Table 29-1). As previously discussed, the following receptors are in the CTZ: serotonin (5-HT3), dopamine (D2), histamine, and muscarinic. Drugs that block serotonin (5-HT3) receptors are ondansetron (Zofran), dolasetron (Anzemet), granisetron (Kytril), or palonosetron (Aloxi) and the drugs that block the dopamine (D2) receptors are droperidol (Inapsine), prochlorperazine (Compazine), or metoclopramide (Reglan). For the histamine receptors, promethazine (Phenergan) or diphenhydramine (Benadryl) can be given. For the muscarinic receptors, atropine, glycopyrrolate (Robinul), or scopolamine patches can be used. Dexamethasone (Decadron) is often administered in combination with a serotonin (5-HT3)–blocking drug and dopamine (D2)–blocking agent. Another neurotransmitter of interest is substance P, which belongs to the tachykinin family of neurotransmitters, known as neurokinins. Substance P has the greatest affinity for neurokinin 1 (NK-1) receptors, which are found centrally in the brainstem vomiting center and peripherally in the gastrointestinal tract. Currently, the only available medication that targets these neurokinin 1 receptors is aprepitant (Emend), available orally for prophylaxis of PONV.

FIG. 29-6 Postoperative management of postanesthesia nausea and vomiting (PONV): PACU Phase I and Phase II.

(From American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses: Evidence-based clinical practice guideline for the prevention and/or management of PONV/PDNV, J Perianesth Nurs 21:230–250, 2006.)

Implications for practice

The use of preoperative steroids in patients who have had laparoscopic cholecystectomy surgery improved quality-of-recovery scores in all areas, including pain, fatigue, and nausea. More research needs to be conducted in this area to determine whether the use of steroids affects quality of recovery in other patient populations.

Source: Glenn S, et al: Preoperative dexamethasone enhances quality of recovery after laparoscopic cholecystectomy, Anesthesiology 114:882–890, 2011.

Nonpharmacologic interventions

In addition to pharmacologic interventions to manage nausea and vomiting, nonpharmacologic interventions are useful adjuncts. Adequate hydration with IV fluids and modified fasting protocols can help to minimize PONV.15 Aromatherapy (e.g., isopropyl alcohol, peppermint oil) is equal in benefit and risk, and it is easy for the nurse to perform or administer. P6 acupoint stimulation with acupuncture or acupressure techniques has been shown to be effective and is recommended for use.16

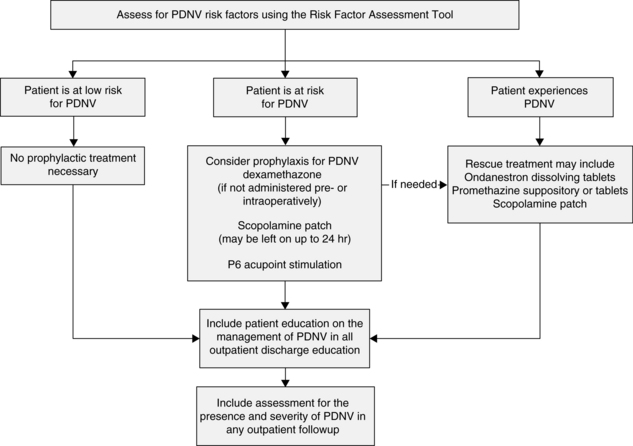

Postdischarge nausea and vomiting

After discharge, up to 30% to 50% of patients undergoing outpatient surgery have postdischarge nausea and vomiting (PDNV).17 PDNV affects the quality of recovery, increases the potential for patient morbidity and hospitalization of patients at high risk, and decreases patient satisfaction. PDNV is defined as nausea and vomiting that occurs up to 24 hours after the patient is discharged from the facility. See Fig. 29-7 for rescue and treatment recommendations. More research is needed to establish the scope of the PDNV problem and the effectiveness of these recommendations.

Other complications

Procedure-related complications

Perforated viscus

Internal organs may be perforated during the operative procedure. Commonly caused by various types of endoscopic procedures (e.g., laparoscopy, gastroscopy), perforations can appear as pain out of proportion to the procedure; a distended, firm abdomen; hypotension, or bleeding. The esophagus, stomach, bladder, uterus, or bowel may be damaged and not noticed until after the patient arrives in the PACU and becomes symptomatic. The nurse should call the surgeon immediately, provide hemodynamic support as ordered (fluid resuscitation, blood component therapy, vasoactive medications, positioning, additional line placement), and analgesia or sedation if appropriate. The nurse may need to prepare for emergent transfer to the operative suite for repair of the perforation.

Other emergencies

Allergic reactions or anaphylaxis

The nurse should respond immediately when a patient exhibits signs and symptoms of an allergic or potential anaphylactic reaction. The nurse should stop the administration of drugs, attempt to reduce the absorption of the offending agent, maintain the airway, and administer 100% oxygen. Intubation may need to be considered, particularly if significant respiratory distress or laryngeal swelling is present. Fluid bolus for volume expansion is initiated. Epinephrine should be administered. Start with 0.1 mL/kg of 1:1000 subcutaneously (subcut) or intramuscularly (IM) or 0.1 mL/kg of 1:10,000 IV (maximal dose, 5 mL) and titrate to effect on the basis of physician orders. Secondary treatment includes antihistamines, glucocorticoids, continuous catecholamine infusion, and sodium bicarbonate if acid-base status indicates the need. With supportive care, and especially if the patient is not intubated and symptoms continue, continually reevaluate the airway to ensure adequate oxygenation and ventilation.

Transfusion reactions

Nurses in the PACU must be especially adept at assessing the patient receiving blood, because many of the signs and symptoms of an adverse reaction to blood may be difficult to separate from those caused by other variables, such as the patient’s illness, surgery, or medications (including anesthesia). In addition, the patient who is not fully conscious may not report symptoms. Blood transfusion reactions or complications may be either immediate or delayed.18 Immediate reactions include hemolytic, nonhemolytic febrile, and anaphylactic reactions. Other reactions include transmission of infectious disease (acquired disease), graft-versus-host disease, and transfusion-related acute lung injury.

Treatment of immediate reactions

At the first sign of a reaction, the transfusion must be stopped and the physician should be notified. The donor blood is replaced with a new infusion set and normal saline solution. Recheck the patient’s identity and blood label information match. The donor blood unit and administration set, along with a sample of the recipient’s blood (drawn atraumatically from a site other than the IV catheter where the blood was administered), should be sent to the blood bank for transfusion reaction investigation. Urine output must be monitored carefully. Ideally, a urinary catheter should be inserted and hourly output is recorded. Vital signs must be monitored, and the patient is treated according to symptoms. Blood transfusion with properly matched blood may be needed to correct blood volume deficits and control shock. Vasopressors may be necessary to control blood pressure, but must be used with caution because they can contribute to renal damage, especially if blood volume has not been restored. Oxygen and epinephrine may be used to treat dyspnea and wheezing. Steroids and broad-spectrum antibiotics may be necessary to treat reactions caused by bacterial contamination. Antihistamines and antipyretics are given to the patient with an allergic reaction. Diuretic therapy (e.g., furosemide) and the infusion of 0.9% sodium chloride or 5% dextrose in 0.45% sodium chloride may be prescribed to maintain hydration and urine flow of more than 100 mL/h.

Summary

The perianesthesia nurse in the postanesthesia care unit monitors the patient, vigilant and mindful of the potential for complications and adverse events. Proactive and responsive, the nurse reacts with sound clinical judgment to intervene quickly and assertively for the patient. Some complications are minor, transitory, and easily resolved; others are life threatening and require skillful intervention by the nurse and the anesthesia care team to save the patient’s life or avoid permanent injury. All perianesthesia nurses, regardless of the facility size or location, need competence in managing potential postanesthesia complications.

1. Smetana GW, et al. Preoperative pulmonary risk stratification for noncardiothoracic surgery: systematic review for the american college of physicians. Ann Intern Med.2006;144(8):581–595.

2. Udeshi A, et al. Postobstructive pulmonary edema. J Crit Care. 2010;25(3):538.e531–538.e535.

3. Van Kooy MA, Gargiulo RF. Postobstructive pulmonary edema. Am Fam Physician. 2000;62(2):401–404.

4. Desciak MC, Martin DE. Perioperative pulmonary embolism: diagnosis and anesthetic management. J Clin Anesth.2011;23(2):153–165.

5. Fleisher LA, et al. 2009 ACCF/AHA focused update on perioperative beta blockade incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and care for noncardiac surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(22):e13–e118.

6. Bijker JB, et al. Incidence of intraoperative hypotension as a function of the chosen definition: literature definitions applied to a retrospective cohort using automated data collection. Anesthesiology.2007;107(2):213–220.

7. Kheterpal S, et al. Preoperative and intraoperative predictors of cardiac adverse events after general, vascular, and urological surgery. Anesthesiology. 2009;110(1):58–66.

8. Krassioukov A, et al. A Systematic review of the management of autonomic dysreflexia after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(4):682–695.

9. Kertai MD, et al. Predicting perioperative cardiac risk. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2005;47(4):240–257.

10. Anderson JL, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-st-elevation myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2011;123(18):e426–e579.

11. Hooper VD, et al. ASPAN’s evidence-based clinical practice guideline for the promotion of perioperative normothermia: second edition. J Perianesth Nurs.2010;25(6):346–365.

12. Brice DD, et al. A simple study of awareness and dreaming during anaesthesia. British Journal of Anaesthesiology. 1970;42:535–542.

13. Murphy MJ, et al. Identification of risk factors for postoperative nausea and vomiting in the perianesthesia adult patient. J Perianesth Nurs. 2006;21(6):377–384.

14. American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses (ASPAN): Evidence-based clinical practice guideline for the prevention and/or management of PONV/PDNV. J Perianesth Nurs.2006;21(4):230–250.

15. Couture DJ, et al. Therapeutic modalities for the prophylactic management of postoperative nausea and vomiting. J Perianesth Nurs. 2006;21(6):398–403.

16. Mamaril ME, et al. Prevention and management of postoperative nausea and vomiting: a look at complementary techniques. J Perianesth Nurs.2006;21(6):404–410.

17. Odom-Forren J, et al. Evidence-based intervention for post discharge nausea and vomiting: a review of the literature. J Perianesth Nurs.2006;21(6):411–430.

18. Eder AF, Chambers LA. Noninfectious complications of blood transfusion. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131(5):708–718.

Ali SZ, et al. Malignant hyperthermia. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2003;17(4):519–533.

American Association of Critical-Care Nurses: AACN procedure manual for critical care. ed 6. St. Louis: Saunders; 2011.

American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Intraoperative Awareness: Practice advisory for intraoperative awareness and brain function monitoring. Anesthesiology.2006;104:847–864.

American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses: Perianesthesia nursing standards and practice recommendations 2010–2012. Cherry Hill, NJ: ASPAN; 2010.

Atlee JL. Complications in anesthesia. ed 2. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007.

Bruns JJJr. Anticholinergic toxicity. available at www.emedicine.com/EMERG/topic36.htm, December 21, 2011. Accessed

Bycroft J, et al. Autonomic dysreflexia: a medical emergency. Postgrad Med J.2005;81:232–235.

Cullen DJ, et al. Spinal epidural hematoma occurrence in the absence of known risk factors: a case series. J Clin Anesth.2004;16(5):376–381.

Finucane BT, et al. Principles of airway management, ed 4. New York: Springer; 2011.

Joint Commission: Preventing, and managing the impact of, anesthesia awareness, Sentinel Event Alert 32:2004. available at: www.jointcommission.org/sentinel_event_alert_issue_32_preventing_and_managing_the_impact_of_anesthesia_awareness/, December 21, 2011. Accessed

Kardon E. Transfusion reactions. available at www.emedicine.com/emerg/topic603.htm, December 21, 2011. Accessed

Klingensmith ME. Washington University Department of Surgery in St. Louis: The Washington manual of surgery. ed 6. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011.

Lepouse C, et al. Emergence delirium in adults in the post-anaesthesia care unit. Br J Anaesth. 2006;96(6):747–753.

Osborne GA, et al. Crisis management during anaesthesia: awareness and anaesthesia. Qual Saf Health Care.2005;14(3):e16.

Ruskin K, Rosenbaum SH. Anesthesia emergencies. New York: Oxford University Press; 2011.

Vlajkovic GP, Sindjelic RP. Emergence delirium in children: many questions, few answers. Anesth Analg.2007;104(1):84–91.

Valchanov K, et al. Anaesthetic and perioperative complications. Cambridge: Cambridge University; 2011.