57 Cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the pacu

Antiarrhythmics: A group of drugs used to suppress abnormal rhythms of the heart.

Cardiopulmonary Arrest: The cessation of normal circulation of the blood because of failure of the heart to contract effectively.

Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR): An emergency procedure that is performed in an effort to return life to a person in cardiac arrest.

Chest Compression: An emergency procedure that is performed on a person in cardiac arrest in an effort to create artificial circulation by manually pumping blood through the heart.

Defibrillation: A treatment for the life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias that consists of delivering a therapeutic dose of electrical energy to the heart, which depolarizes a critical mass of the heart muscle, terminates the arrhythmia, and allows normal sinus rhythm to be reestablished via the patient’s sinoatrial node.

Differential Diagnosis: A systematic method, essentially a process of elimination, used to identify unknowns.

Vasopressors: Sympathomimetic drugs that mimic the effects of the sympathetic nervous system.

Cardiopulmonary emergencies are common in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU). PACU and perianesthesia nurses must keep their cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) skills and knowledge base up to date to most effectively respond to this potentially devastating event. In October 2010, the American Heart Association (AHA) Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care (ECC) were published in Circulation. This CPR update was based on an international evidence-based evaluation process involving hundreds of resuscitation experts.1

Ethical issues related to cardiopulmonary resuscitation

Many patients are increasingly concerned about the inappropriate use of life-sustaining procedures that can have a dramatic effect on the length and quality of life. Consequently, increasing numbers of patients place limitations on medical treatments that may affect their lives in the future, through the use of living wills, advanced directives, do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders, and no-CPR programs. Living wills allow a person to express preferences concerning end-of-life medical care. Some states have adopted DNR and no-CPR programs with focus on the use or extent of resuscitation efforts. Advanced directives are usually prepared by the physician attending critically or terminally ill patients who are unable to make decisions for themselves. These directives are based on the patient’s living will, if one exists. The patient’s right to limit medical interventions is firmly established in modern medical practice.2,3

The operating room, however, is one area in which restrictions on cardiopulmonary resuscitation have caused considerable ethical conflicts between patients and health care providers. Approximately 75% of all cardiac arrests in the operating room are related to specific anesthesia or surgical causes, such as an accidental overdose of an anesthetic agent. In these circumstances, resuscitation has been found to be highly successful. As such, many health care providers view honoring a patient’s DNR order as failure to treat a reversible process and thus similar to committing murder.3,4 One could argue that the same ethical dilemma exists in the PACU because it is so closely aligned with surgery. All the various ethical dilemmas concerning DNR orders that may arise in the PACU and other topics related to advanced directives are beyond the scope of this chapter. As such, PACU nurses must be thoroughly familiar with their individual institution’s policies and guidelines concerning these issues.

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

Urgency of cardiopulmonary resuscitation

During cardiopulmonary arrest, time is a factor that profoundly influences patient outcomes. The probability of survival decreases rapidly with each minute of cardiopulmonary compromise. The survival rate from cardiac arrest caused by ventricular tachycardia decreases approximately 7% to 10% for each minute the patient is deprived of defibrillation.5 Therefore the PACU nurse must respond quickly and efficiently during all cardiopulmonary emergencies.

Indications for resuscitation

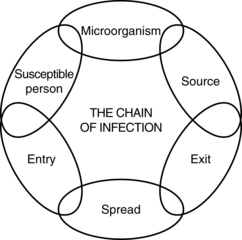

Respiratory compromise appears to be the primary cause of morbidity in the PACU. Respiratory compromise can result from residual anesthesia, upper airway obstruction, laryngeal edema, laryngospasm, bronchospasm, noncardiogenic pulmonary edema, and aspiration.6

One of the most common causes of upper airway obstruction in the postanesthetic patient results from mechanical obstruction from the tongue. This situation occurs when the tongue falls back into a position that mechanically obstructs the pharynx and thus blocks the passage of air to and from the lungs. The underlying cause of this obstruction may be the result of residual anesthetics, opioids, or muscle relaxants administered during surgery. The tongue may also be edematous from surgical manipulation, anatomic deformities, or allergic reaction. Clinical signs of this type of obstruction include snoring, flaring of the nostrils, use of accessory muscles for ventilation, retraction of the intercostal spaces and suprasternal notch, asynchronous movements of the chest and abdomen, tachycardia from hypoxia, and decreased oxygen saturation.3,6

Arterial carbon dioxide pressure (PaCO2) increases 6 mm Hg during the first minute of total obstruction, with an additional 3 to 4 mm Hg increase each passing minute.7 If the obstruction is not corrected, the patient’s condition will continue to deteriorate resulting in cardiopulmonary arrest. This occurrence is especially tragic when the obstruction could have been corrected by simply stimulating the patient to take deep breaths or by repositioning the airway via a chin lift or jaw thrust. (These maneuvers will be discussed in more detail later.) Additional techniques include the use of a nasal or oral airway. When deciding which of these two airways to use, the PACU nurse should remember that the nasal airway is usually less stimulating and thus tolerated better in the patient emerging from general anesthesia. The nasal airway should, however, not be used with patients with known or suspected basal skull fractures, because of the possibility of inadvertent intracranial placement of the airway. Nasal airways should also not be used with patients presenting with severe coagulopathy due to the increased incidence of nasal bleeding associated with insertion of the nasal airway.8

If the obstruction persists, advanced airway management procedures with the esophageal-tracheal Combitube, Laryngeal Tube or King LT, laryngeal mask airway, or endotracheal tube may be indicated. Obviously, prevention of cardiopulmonary arrest is more desirable than treatment. When a cardiopulmonary arrest does occur, emergency procedures must be administered rapidly and decisively before irreversible damage occurs.8

Emergency equipment

The routine use of various monitoring modalities in the PACU is invaluable for the diagnosis of many developing patient complications that could precipitate a cardiopulmonary arrest. The use of pulse oximetry, for example, can be extremely helpful in the diagnosis of problems concerning patient oxygenation, as in the case of a progressing airway obstruction. The use of a capnograph may be helpful in the early detection of adverse respiratory events such as hypoventilation. The routine use of an ECC monitor assists the nurse in identifying life-threatening arrhythmias such as pulseless ventricular tachycardia (VT), ventricular fibrillation (VF), asystole, and pulseless electrical activity (PEA). These and other monitoring modalities provide the nurse with a more definitive means of diagnosis and opportunity for early intervention.8

Management of cardiac arrest

Assess for responsiveness

At the first sign of potential trouble, the nurse should immediately assess the responsiveness of the patient. The last thing the nurse wants to do is prematurely call a code and start CPR only to find out that the patient had just fallen asleep and one of the electrocardiogram (ECG) leads was loose or disconnected. At the same time the PACU nurse is checking the patient’s responsiveness, the patient’s breathing status should also be assessed; this should be a visual inspection for abnormal (only gasping) or lack of breathing.9

Circulatory assessment

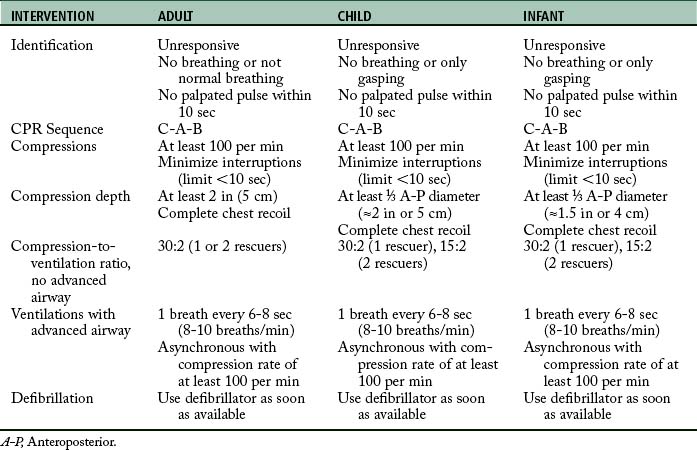

Once unresponsiveness has been confirmed and the emergency system has been activated, the PACU nurse should immediately precede with the AHA basic life support and advanced cardiac life support protocols. The nurse should now proceed to evaluate the patient’s circulatory status. For an adult and child, this assessment is performed by palpating the carotid artery for no more than 10 seconds. If the patient is an infant, the brachial artery should be palpated.9

If a pulse is detected, the patient’s lungs should be ventilated using one of the unit’s readily available bag-mask devices. Respirations should be delivered at a rate of one breath every 5 to 6 seconds or approximately 10 to 12 breaths/min. Each breath should be given over 1 second and cause a visible chest rise. The patient’s pulse should be checked every 2 minutes. This process should continue until the emergency response team can determine and correct the underlying cause of the respiratory arrest or initiate more advanced treatment.9

If no pulse is detected within 10 seconds, the 2010 AHA Guidelines for CPR and ECC state that cardiac arrest should be assumed and CPR initiated immediately. These guidelines recommend initiating a CPR sequence of (1) chest compressions, (2) airway, and (3) breathing (CAB). Anytime during this sequence, defibrillation should be initiated as soon as a defibrillator is available.9

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

Chest compressions

As stated previously, cardiac arrest can be caused by four heart rhythms: VF, pulseless VT, PEA, and asystole. VF consists of disorganized electrical activity in which VT consists of organized electric activity of the ventricular myocardium. The electrical activity exhibited in these rhythms is insufficient to generate enough forward blood flow to sustain life. PEA encompasses a group of organized electrical rhythms with insufficient or absent mechanical ventricular activity. Although this rhythm may generate ventricular electrical activity on the monitor, the ventricle does not mechanically respond, resulting in the absence of a clinically detectable pulse. PEA has previously been referred to as electromechanical dissociation or nonperfusing rhythm. Asystole, also known as ventricular asystole, consists of the absence of detectable ventricular activity with or without atrial electrical activity.8

Ventricular fibrillation and pulseless ventricular tachycardia

During the first few minutes of witnessed VF cardiac arrest, the primary limiting factor for the delivery of oxygen to the heart and brain is blood flow and not arterial oxygen content. As a result, in the initial step of CPR, uninterrupted chest compressions take priority over positive pressure ventilation.8 External cardiac compression should be performed with the patient in a horizontal position on a firm surface. If a bed board is to be used, care must be taken not to delay the initiation of compressions while one is being retrieved. If the patient is on an air-filled mattress, the mattress should be deflated when performing CPR.10

To begin compressions, the rescuer should be positioned at the patient’s side. The rescuer should place the heel of one hand on the center (middle) of the chest between the patient’s nipples (the lower half of the sternum; Fig. 57-1). The heel of the rescuer’s free hand should be placed on top of the hand already positioned on the patient’s chest. The rescuer should keep the arms straight with shoulders directly over the adult patient’s sternum. The adult sternum should be depressed at least 2 inches (5 cm; Fig. 57-2). Rescuers should “push hard, push fast” at a rate of at least 100 compressions/min. Evidence appears to support the premise that this rapid compression rate effectively benefits the patient in terms of blood flow and blood pressure. Interruptions to chest compression should always be minimized to as few as possible with each interruption lasting less than 10 seconds. The chest should be allowed to completely recoil after each compression. Incomplete recoil has been associated with high intrathoracic pressures and decreased hemodynamics, including decreased coronary perfusion, cardiac index, myocardial blood flow, and cerebral perfusion. If two rescuers are present, it is recommended that they rotate giving compressions every 2 minutes. This is done to prevent rescuer fatigue, which can lead to decreased compression effectiveness such as insufficient rate, depth of compression, and incomplete recoil of the chest. It has been found that significant fatigue and shallow compressions are common after 1 minute of CPR, although the rescuer might not recognize that fatigue affecting effective compressions is present. Rescuers should consider switching roles during any intervention that is associated with appropriate interruptions in chest compressions such as defibrillation. The rescuers should strive to accomplish this switch in less than 5 seconds.9 The actual ratio between ventilations and chest compressions will be discussed in the third segment of the CABs, which addresses breathing.

Source: Fried DA, et al: The prevalence of chest compression leaning during in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation, Resuscitation 82(8):1019–1024, 2011.

In children, the sternum is compressed with the heel of one hand only. In infants, the sternum is compressed with the tips of two fingers for one rescuer or the thumbs of the encircling hands of the rescuer when two rescuers are present (Figs. 57-3 and 57-4).11 The compression depth for children should be one third the anteroposterior (A-P) diameter of the chest or approximately 2 inches (5 cm). When treating an infant, the compression depth should be one third the A-P diameter or approximately 1.5 inches (4 cm). As in adults, a rate of at least 100 compressions/min is also recommended for children and infants.9

The nurse ventilating the patient’s lungs should periodically check the patient’s pulse during compressions as a guide for their effectiveness. If external cardiac compression is done correctly, systolic blood pressure will reach 60 to 80 mm Hg with a diastolic pressure of zero. Mean blood pressure in the carotid artery will seldom exceeds 40 mm Hg. Cardiac output from chest compression is approximately one fourth to one third of normal. As a result, compressions must be regular, smooth, and uninterrupted.12

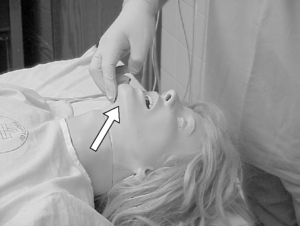

Airway

After chest compressions have been started, rescue breaths by mouth-to-mouth or bag-mask should be delivered. During the initial evaluation of the patient’s responsiveness, the rescuer has already observed the patient’s respiratory status and determined that the patient is not breathing. To facilitate ventilations, particular airway maneuvers should be performed. The PACU nurse should use the head tilt–chin lift maneuver to open the patient’s airway if no evidence of cervical spine trauma exists. The head tilt maneuver is accomplished by simply tilting the patient’s head backward and hyperextending the neck (Fig. 57-5). The chin lift involves placing two fingers under the bony portion of the lower jaw, near the chin, and pushing the patient’s chin upward with moderate pressure (Fig. 57-6). The head tilt–chin lift maneuver is simply a combination of both these maneuvers (Fig. 57-7). For patients with actual or possible cervical spine injury, the airway should be opened using only a jaw thrust without the head extension maneuver. To perform the jaw thrust, the rescuer is positioned at the head of the patient. The rescuer places one hand on each side of the patient’s head and grasps the angles of the patient’s lower jaw and lifts with both hands (Fig. 57-8). If the jaw thrust does not open the airway in a patient with possible cervical spine injury, the head tilt–chin lift maneuver should be used because adequate ventilation is a priority in CPR.9

FIG. 57-7 Head tilt and chin lift maneuvers are often done collectively.

(Courtesy Department of Nurse Anesthesia, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Va.)

Early in the CPR process, a decision should be made concerning the need for an advanced airway. Because the insertion of an advanced airway may necessitate the interruption of chest compressions for many seconds, the rescuer must weigh the need for compressions against the need for an advanced airway device. Deference of insertion of an advanced airway until the patient fails to respond to initial CPR and defibrillation or shows return of spontaneous circulation is acceptable.9

Recommended advanced airway devices include: esophageal-tracheal Combitube, Laryngeal Tube or King LT, laryngeal mask airway, or endotracheal tube. The esophageal-tracheal Combitube, Laryngeal Tube or King LT, laryngeal mask airway are classified as supraglottic airways. Unlike endotracheal intubation, subglottic airways do not require visualization of the glottis. As a result, training and maintenance of skills with these devices are usually easier as compared to endotracheal intubation. In addition, because direct visualization of the glottis is not necessary, a subglottic airway can be inserted without interruption of chest compressions.8

When the patient’s airway is secured, proper placement of the advanced airway device should be confirmed. This confirmation is especially critical when endotracheal intubation is performed, because of the high risk of tube misplacement, displacement, and obstruction. Confirmation of proper endotracheal tube placement should be assessed with auscultation of the lungs to determine whether breath sounds are present and bilaterally equal in both lungs. Auscultation over the epigastric region is an additional method to confirm misplacement of the endotracheal tube in the esophagus. In addition to auscultation, a confirmation device such as an exhaled CO2 detector or an esophageal detector device can also be used. If a capnogram is available, the presence of end-tidal carbon dioxide should be confirmed along with oxygen saturation with an oxygen saturation monitor. A continuous wave from capnography in addition to clinical assessments is considered the most reliable method of confirming and monitoring correct endotracheal tube placement. When proper placement has been confirmed, the advanced airway should be secured in place to prevent displacement and dislodgement. This can be accomplished with tape or in the case of an endotracheal tube, with a specially designed endotracheal tube holder.1

Breathing

Coronary perfusion pressure gradually rises with consecutive compressions; therefore a ratio of 30 compressions to 2 ventilations is recommended for adults, without advanced airways, whether one or two rescuers are present. When the patient is a child or infant, one rescuer should use a 30:2 compression-to-ventilation ratio. If two rescuers are present, a 15:2 compression-to-ventilation ratio should be used.9

When an advanced airway device is in place, a continuous and uninterrupted compression rate of 100 compressions/min should be maintained. Ventilations of 1 breath every 6 to 8 seconds or 8 to 10 breaths/min should be simultaneously delivered without interruption of the compression rate. Each breath should take 1 second to deliverer with a resulting visible chest rise. Studies suggest that a tidal volume of 8 to 10 mL/kg will maintain normal oxygenation and eliminations of carbon dioxide (CO2). During CPR, oxygen uptake from the lungs and CO2 delivery to the lungs are reduced because cardiac output is approximately 25% to 33% of normal. Therefore a lower-than-normal minute ventilation can maintain effective oxygenation and ventilation of the patient’s lungs. With the adult patient, a CPR tidal volume of approximately 500 to 600 mL should be adequate.8 Excessive ventilation should be avoided because it has been implicated with gastric inflation resulting in regurgitation and aspiration. Excessive ventilation can also cause increased intrathoracic pressure, decreased venous return to the heart, and decreased cardiac output and survival.13 The patient should be assessed rapidly for spontaneous breathing and circulation approximately every five cycles (2 minutes) of CPR. During this assessment, chest compressions should be interrupted for no longer than 10 seconds.1

The vast majority of patients in the PACU will have intravenous (IV) infusions and will be connected to various monitors including the ECG, pulse oximeter, and other monitors for blood pressure and temperature. If for some reason the patient’s IV catheter has been discontinued or not all monitoring devices are in use (as may be the case when preparing a patient for discharge or transfer from the PACU) intravenous access should be secured and the patient should be reconnected to an ECG monitor as soon as possible. Remember, interruptions to chest compressions must be kept to a minimum. Cardiac rhythm analysis should be performed and arrhythmias should be treated with appropriate pharmacologic interventions. Vital signs such as blood pressure, pulse rate, and temperature should also be monitored and assessed.8

Defibrillation

As discussed earlier, as soon as lack of responsiveness has been determined, the rescuer immediately activates the PACU emergency response system and retrieves a defibrillator if it is easily available. In the PACU, the code cart with a defibrillator should always be easily available. If on the rare occurrence that the PACU nurse is alone, the defibrillator should be retrieved, connected to the patient, and used as appropriate. The rescuer should then provide high-quality CPR. In the more common PACU scenario, when two or more rescuers are present and unresponsiveness is determined, one rescuer should begin chest compressions while the other activates the emergency response system and retrieves a defibrillator.9

Defibrillation is the most important determinant for survival in adult VF and VT. If the patient is not already being monitored, the patient should be connected to an ECG monitor or defibrillator with monitoring capabilities. Rhythm assessment is imperative for the detection of VF or VT. The PACU nurse must remember that for each minute of persistent VF, the patient’s chance of survival decreases. Survival rates are highest when immediate CPR is provided and defibrillation is performed within 3 to 5 minutes from the onset of the arrest. After VF or VT have been identified, the defibrillation sequence should start immediately.1

Automated external defibrillators (AEDs) are reliable computerized devices that use voice and visual prompts to guide the rescuer to safely defibrillate VF and pulseless VT. Some of the newer AEDs will record information concerning frequency and depth of chest compressions, prompting the rescuer to achieve more effective CPR performance.5

Although AEDs are gaining popularity in hospital settings, conventional defibrillators are still used in many PACUs and other hospital specialty areas. PACU nurses must have a working knowledge of all defibrillators available in their respective units whether they are the older monophasic or the newer biphasic models. Although biphasic waveform defibrillators have equivalent or higher efficiency for terminating VF when compared to the monophasic waveform defibrillators, many hospital units still use the older monophasic models.6

When the nurse uses the conventional (manual) defibrillator, a basic protocol should be followed. As soon as the defibrillator is brought to the patient’s bedside, it should be immediately prepared for use. Uninterrupted CPR should be continued while the defibrillator is charging. When determining the energy settings for the unit’s biphasic defibrillator, the nurse should follow the manufacturer’s recommendations and the institution’s protocol (usually 120 to 200 J). If the rescuer is unaware of the effective dose range for the unit’s biphasic defibrillator, the maximum dose of 120 J should be administered. Subsequent energy levels should be equivalent, and higher energy levels considered. If a monophasic defibrillator is being used, a charge of 360 J should be used for the first and all subsequent shocks. AEDs are device specific in the charge they deliver.5

Although cardiac arrest is less common in children than adults, VF has been observed in 5% to 15% of pediatric and adolescent arrests. When treating a pediatric patient, it is acceptable to use an initial dose of 2 to 4 J/kg. If refractory VF is encountered, at least 4 J/kg should be used with higher doses considered, not to exceed 10 J/kg or the adult maximum dose. Some AEDs are equipped with pediatric dose attenuator systems that reduce the delivered energy to a dose suitable for a pediatric patient who is 1 to 8 years old. If a dose attenuator AED is not available, then a regular AED should be used. For infants younger than 1 year, a manual defibrillator should be the rescuer’s first choice, with the dose attenuation AED second. Units that provide care to pediatric patients who are at risk for cardiac arrest should have immediate access to a manual defibrillator that is capable of dose adjustment.5

When a manual defibrillator is being used, the lead selection switch should be switched to “paddles” or “pads.” If monitor leads are used, then lead I, II, or III should be selected. Paddles should have specific defibrillation gel or paste applied to them before they are positioned on the patient’s chest. This gel or paste maximizes current flow by reducing transthoracic impedence between the paddles and the patient’s chest. If the defibrillator uses adhesive conductor pads instead of paddles, they should be positioned on the patient’s chest at this time. Four pad or paddle positions—anterolateral, anterior-left infrascapular, anteroposterior, and anterior–right-infrascapular, are equally effective in treating atrial and ventricular arrhythmias. For ease of placement, the anterolateral position is the most common. With this position, one paddle or pad should be positioned just to the right of the patient’s upper sternal border, below the clavicle. The second paddle or pad should be placed on the left side of the patient’s chest slightly to the left of the nipple, with the center of the electrode in the midaxillary line (Fig. 57-9). Often the defibrillator’s manufacturer marks the paddles or pads to designate position on the patient. Next, the monitor display should be visually checked for rhythm assessment. If VF or VT are present, the operator should announce to all team members that the defibrillator is being charged and everyone should stand clear. The charge button on the defibrillator or apex paddle should be pressed. As soon as the defibrillator is charged, the operator should firmly announce to all present that the patient is about to be shocked. No one should be in direct or indirect contact with the patient during defibrillation, which means that no one is touching the patient or any item or apparatus in contact with the patient, including the stretcher or bed. If the rescuer is in direct or indirect contact with the patient during defibrillation, the electric shock may pass through the patient to the rescuer, resulting in a potential second arrest scenario. To alleviate this danger, the AHA suggests the following chant be used. First, the defibrillator operator states loudly and clearly, “I am going to shock on three. One, I’m clear.” At this time, the operator checks to be sure he or she is clear of any contact with the patient. Next, the operator states, “Two, you’re clear,” and makes a visual check to ensure that no one else is touching the patient or any item that is in contact with the patient. Finally, the operator announces, “Three, everybody’s clear.” At this point, the operator checks everyone, including himself or herself, one last time before administering the shock to the patient. If pads are used instead of paddles, pressing the defibrillator discharge button discharges the defibrillator. With paddles, the operator should apply approximately 25 lb of pressure on the paddles while simultaneously pressing both paddle discharge buttons.14

After the charge has been delivered to the patient, CPR should be resumed immediately and continued for five cycles, after which the patient’s rhythm should be again evaluated.1 As long as VF or VT persist, attempts to defibrillate must continue. The PACU nurse must remember that as long as the patient’s myocardium has the energy to produce VF or VT, it should also have the energy to produce a perfusing rhythm.8

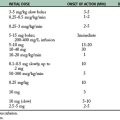

In the case of VT or VF, as soon as the defibrillator is available one shock is delivered. Immediately after this shock, CPR is continued for five cycles (approximately 2 minutes), at which time the patient’s rhythm is evaluated. If the VT or VF persists, the patient should be shocked once again with CPR immediately following. As soon as IV or intraosseous (IO) access is available, a vasopressor (epinephrine, 1 mg IV or IO) repeated every 3 to 5 minutes or one dose of vasopressin (40 units IV or IO to replace the first or second dose of epinephrine) should be given during CPR before or after the shock.1 Additional pharmacologic interventions that may be considered include the administration of amiodarone, lidocaine, and magnesium. Magnesium is considered in the case of magnesium deficiency or for the treatment of torsades de pointes.1 A summary that compares resuscitation interventions across age groups is presented in Table 57-1.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis consists of determining the underlying cause of the arrest. The primary purpose of the differential diagnosis is identification of reversible causes that have a specific therapy. For the PACU nurse, this diagnosis may involve reviewing the patient’s preoperative history and physical condition, preoperative and postoperative laboratory values, postoperative diagnosis, surgical procedure performed, and condition on arrival into the PACU. It should also involve the patient’s intraoperative course, including unexpected surgical events such as excessive blood loss, fluid replacement, pharmacologic management, and any other intraoperative surgical or anesthetic events. Any of these factors may add some insight into the underlying question of why the patient has suffered a cardiac arrest. Potentially reversible causes of an arrest include hypovolemia, hypoxia, acidosis, hypokalemia, hyperkalemia, hypoglycemia, hypothermia, drug overdoses, cardiac tamponade, tension pneumothorax, coronary or pulmonary thrombosis, and trauma. The PACU nurse should remember that successful resuscitation outcomes usually depend on the discovery and treatment of these or other reversible underlying causes.8

Asystole and pulseless electrical activity

Thus far, the discussion of managing cardiac arrest has focused on pulseless VT and VF. The following sections will examine two other life threatening arrhythmias: asystole and PEA. Looking at the patient’s monitors, the PACU nurse may observe that the patient’s rhythm on the ECG monitor is flat or straight-line. The nurse should remember that asystole is a specific diagnosis, but that a flat line is not. Many nonphysiologic reasons could explain why the monitor may be flat or straight-line. One of the most common causes is that one of the monitor leads becomes disconnected or unplugged. A change in lead selection may also assist the nurse in identification of a disconnected lead. Monitor failure or an insufficient gain setting may also cause a straight-line wave.2

A straight-line ECG rhythm may also indicate that the patient is in cardiopulmonary arrest. The PACU nurse should approach this situation in the same way as other potential cardiopulmonary emergencies. The first step to be taken is to assess patient consciousness. If the patient is awake and talking, without any distress, true asystole is unlikely. While assessing consciousness, the nurse may discover that the patient was merely sleeping and inadvertently became disconnected from one of their monitor leads. If, however, the nurse confirms that the patient is unconscious and unresponsive the, unit’s emergency response system should be immediately activated. The nurse should then immediately follow with the CPR sequence of CAB. Asystole is commonly considered an end-stage rhythm that usually follows VF or PEA, resulting in a generally poor prognosis.8 If the patient is confirmed to be in asystole, defibrillation is not recommended.1

During asystole, shocks may be harmful by producing a “stunned heart” and profound parasympathetic discharge. As a result, the AHA considers the practice of empiric shocking of asystole to have no evidence of support and to be harmful to the patient.14

With asystole, uninterrupted CPR should continue. As soon as IV or IO access is available, epinephrine (1 mg intravenous push IV or IO) should be administered every 3 to 5 minutes. Vasopressin (40 units IV or IO) can be given as a replacement for the first and second doses of epinephrine. Drugs should be delivered immediately after rhythm assessments without interruption of CPR. After drug administration and approximately five cycles of CPR, the patient’s rhythm should be reassessed. During this time, the rescuers should be continuously searching for and treat identified reversible causes of the arrest as presented in the differential diagnosis. Evidence suggests that the routine use of atropine during asystole has little therapeutic benefit.8

PEA is a little deceptive in its presentation in that it mimics an organized perfusing rhythm on the monitor, but no perfusing pulse is present when the pulse is palpated. As with asystole, the CPR sequence of CAB should be followed without defibrillation. Epinephrine (1 mg IV or IO push) should be administered every 3 to 5 minutes. Vasopressin (40 units IV or IO) may be given as a replacement for the first and second doses of epinephrine. As with asystole, the routine use of atropine has little therapeutic benefit. Drugs should be delivered immediately after rhythm assessments without interruption of CPR. After drug administration and approximately five cycles of CPR, the patient’s rhythm should be reassessed. During this process, the rescuers must always remember to continuously search for and treat identified reversible causes of the arrest as presented in the differential diagnosis. This is especially the case with PEA. PEA is frequently caused by reversible conditions that may have caused the arrest or are complicating the resuscitation efforts such as hypoxemia and hypovolemia. Correction of these reversible conditions often leads to a successful patient recovery.8

Recovery

If adequate spontaneous circulation returns without spontaneous breathing, rescue breathing should continue but compressions should be terminated. Hyperventilation should be avoided because of the potential for increasing intrathoracic pressure and decreasing cardiac output. Hyperventilation also has the adverse potential to decrease cerebral blood flow. Ventilation may be started at 10 to 12 breaths/min and titrated to achieve a partial pressure of end-tidal CO2 of 35 to 40 mm Hg as monitored by capnometry.15

As recommended by the AHA, the initial objectives of postcardiac arrest care are:

• The optimization of cardiopulmonary function and perfusion of vital organs

• The transport of the postcardiac arrest patient to an appropriate critical care unit capable of providing comprehensive postcardiac arrest care

• The identification and treatment of all precipitating causes of the arrest and the prevention of recurrent arrest

Subsequent objectives include:

• Body temperature control to optimize survival and neurological recovery

• Identification and treatment of acute coronary syndromes.

• Optimization of mechanical ventilation to minimize lung injury

• Decreased risk of multiorgan injury and support of organ function as required

• Objective assessment of the patient’s prognosis for recovery

• Assisting the survivors with required rehabilitation services14

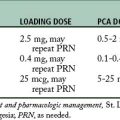

Pharmacologic therapy

The following short summary is based on the AHA recommendations concerning various drugs that are commonly used during cardiovascular resuscitation.5 The PACU nurse should have a thorough understanding of every drug found in the PACU code cart, including indications, contraindications, interactions, dosage, and adverse reactions.

Vasopressors

Epinephrine

The adrenergic effect of epinephrine increases myocardial and cerebral blood flow and may improve return of spontaneous circulation during CPR. The recommended dose of epinephrine hydrochloride is 1.0 mg (10 mL of a 10:000 solution) IV every 3 to 5 minutes during adult cardiac arrest. Epinephrine can also be administered via the endotrachea tube at a dose of 2 to 2.5 mg. if IV or IO access has not been secured.8

Vasopressin

Vasopressin is a naturally occurring antidiuretic hormone. In high doses, higher than those needed for antidiuretic effects, vasopressin acts as a nonadrenergic peripheral smooth muscle vasoconstrictor. Vasopressin has been found useful as an alternative to epinephrine for the treatment of adult shock-refractory VF and increase recovery of spontaneous circulation in the event of asystole or PEA. For patients in pulseless arrest, the recommended one time adult dose of vasopressin is 40 units IV/IO, which can be given to replace the first or second dose of epinephrine.8

Antiarrhythmics

Amiodarone

Amiodarone affects potassium, sodium, and calcium channels. It has both alpha and beta adrenergic blocking properties. Amiodarone may be considered for VF, pulseless VT that is unresponsive to CPR, defibrillation, and vasopressor therapy. The initial dose of amiodarone is 300 mg IV, which can be followed by one additional dose of 150 mg IV.8

Lidocaine

Lidocaine can be considered if amiodarone is not available. During cardiac arrest, it is administered as a bolus of 1.0 to 1.5 mg/kg IV. If pulseless VT persists, additional doses of 0.5 to 0.75 can be administered IV push at 5 to 10 minute intervals to a maximum dose of 3 mg/kg. Side effects include slurred speech, muscle twitching, altered consciousness, respiratory compromise, seizures, and tachycardia.1

Magnesium

Magnesium is used during a cardiac arrest when the arrhythmia is suspected of being caused by magnesium deficiency or the presence of torsades de pointes. When VF or pulseless VT cardiac arrest is associated with torsades de pointes, magnesium sulfate can be administered slowly IV at 1 to 2 g diluted in 10 mL of 5% dextrose in water.8

Atropine sulfate

Available evidence suggests that the use of atropine sulfate during PEA or asystole has little if any therapeutic benefit and is no longer recommended by the AHA for this use. As an anticholinergic agent, it remains the first line of treatment for symptomatic sinus bradycardia. Atropine sulfate should not be used when Mobitz type II block is suspected. It should always be used with caution in a patient with an acute myocardial infarction since acceleration of the patient’s heart rate may increase ischemia. The recommended dose of atropine sulfate in the presence of bradycardia is 0.5 mg IV every 3 to 5 minutes up to a maximum total dose of 3 mg.8

Sodium bicarbonate

Hyperventilation corrects respiratory acidosis by removing carbon dioxide. Acidemia during cardiac arrest and resuscitation primarily results from a low blood flow. For the maintenance of acid base balance, adequate alveolar ventilation and tissue perfusion must be maintained. Clinical and laboratory data have not conclusively shown that acidosis interferes with defibrillation, restoration of spontaneous circulation, or short-term survival. Most data indicate that the use of buffers does not improve outcomes. Present data do, however, indicate that bicarbonate can compromise coronary perfusion pressure and induce hypernatremia. In addition, it can exacerbate central venous acidosis and cause adverse effects from extracellular alkalosis.1

Sodium bicarbonate can be beneficial in patients with hyperkalemia, tricyclic antidepressant overdose, or preexisting metabolic acidosis. If used, bicarbonate should be administered at an initial dose of 1 mEq/kg. Administration of bicarbonate should be guided by blood gas analysis and laboratory measurements.1

Summary

A cardiopulmonary emergency is not an event that any health care provider looks forward to facing. It is, however, an event that is more common in highly specialized acute nursing units, such as the PACU. Every nurse working in the PACU has the responsibility to be prepared for catastrophic emergencies.

1. Travers AH, et al. Part 4: CPR overview: 2010 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation.2010;122(Suppl 3):S676–S684.

2. Morrison LJ, et al. Part 3: ethics: 2010 Amercian Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation.2010;122(Suppl 3):S665–S675.

3. Barash P, et al. Clinical anesthesia, ed 6. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009.

4. Walker R. DNR in the OR: resuscitation as an operating room risk. JAMA. 1991;266:2407.

5. Link MS, et al. Part 6: electrical therapies: automated external defi brillators, defi brillation, cardioversion, and pacing: 2010 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2010;122(Suppl 3):S706–S7196.

6. Odom J. Airway emergencies in the post anesthesia care unit. Post Anesth Care Nurs. 1993;28:483–491.

7. Nagelhout J, Plaus K. Nurse anesthesia, ed 4. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2010.

8. Neumar RW, et al. Part 8: adult advanced cardiovascular life support: 2010 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation.2010;122(Suppl 3):S729–S767.

9. Berg RA, et al. Part 5: adult basic life support: 2010 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation.2010;122(Suppl 3):S685–S705.

10. Perkins GD, et al. Do different mattresses affect the quality of cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:2330–2335.

11. Hazinski MF, ed. PALS provider manual. Dallas: American Heart Association, 2002.

12. AHA. Part 4: adult basic life support: 2005 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation.2005;112(Suppl 4):IV-19–IV-24.

13. Aufderheide TP, et al. Hyperventilation-induced hypotension during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Circulation. 2004;109:1960–1965.

14. American Heart Association in collaboration with the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation. Guidelines 2000 for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care: international consensus on science. Circulation.2000;102(Suppl 1):8.

15. Pederdy MA, et al. Part 9: post-cardiac arrest care: 2010 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation.2010;122(Suppl 3):S768–S786.