Ascites: Fluid in dependent recesses of peritoneal cavity

Varices: Well-defined, tubular or serpentine collateral vessels with same enhancement as adjacent veins

Varices: Well-defined, tubular or serpentine collateral vessels with same enhancement as adjacent veins

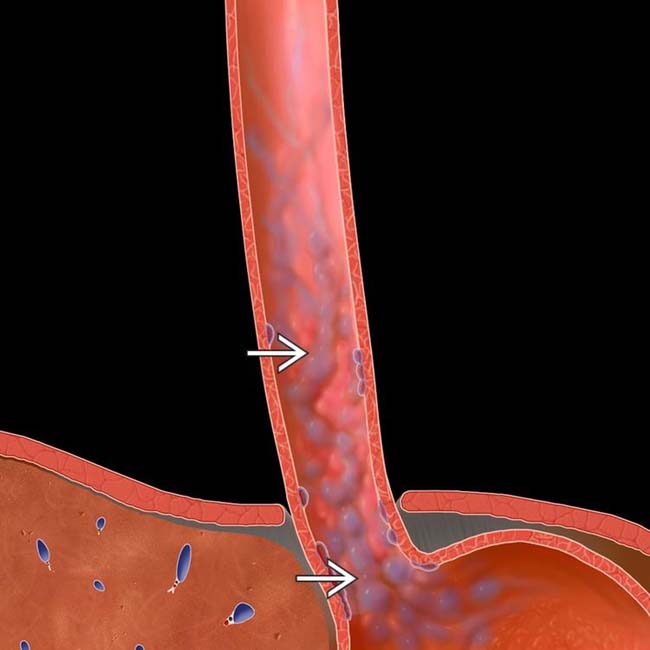

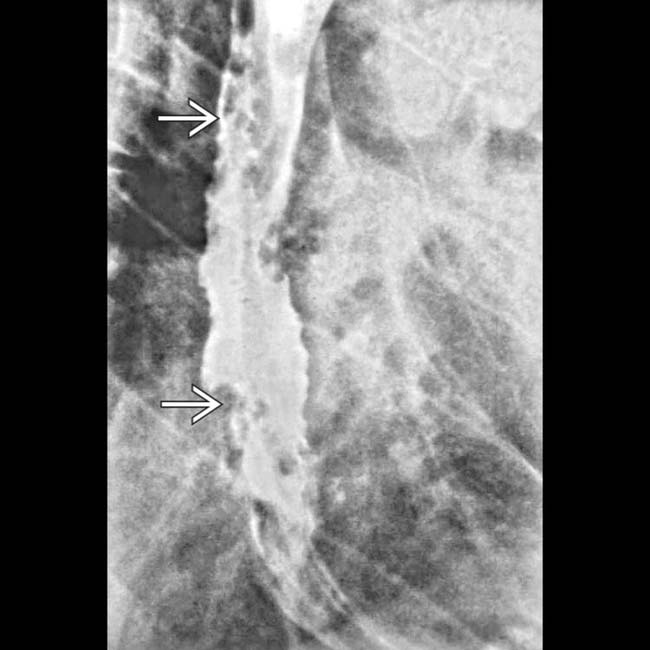

as serpiginous, longitudinally oriented submucosal venous collaterals extending into the gastric fundus.

as serpiginous, longitudinally oriented submucosal venous collaterals extending into the gastric fundus.

in the esophageal wall. Varices are usually pliable and easily compressed. Varicoid carcinoma could have a similar appearance.

in the esophageal wall. Varices are usually pliable and easily compressed. Varicoid carcinoma could have a similar appearance.

in the left upper quadrant in communication with the splenic vein and the left renal vein

in the left upper quadrant in communication with the splenic vein and the left renal vein  , which appears dilated, forming a splenorenal shunt.

, which appears dilated, forming a splenorenal shunt.

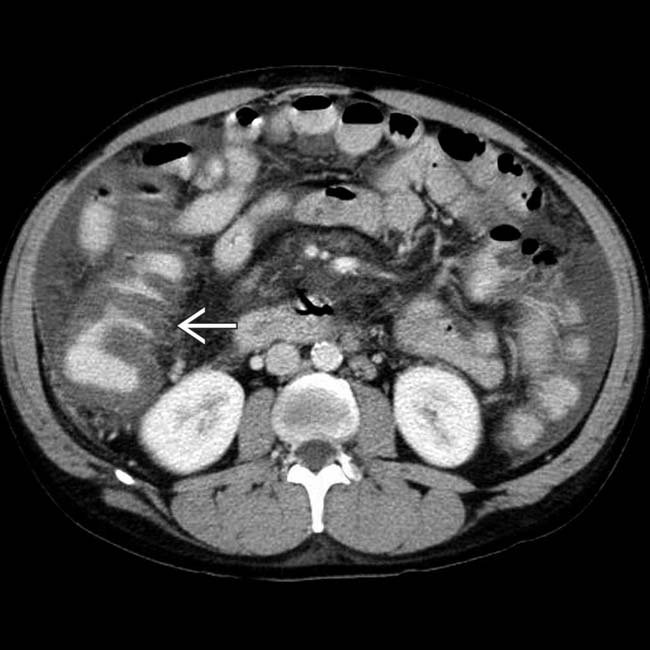

in the portal and superior mesenteric veins, with calcification suggesting chronicity. Portal hypertension increases the risk of portal vein thrombus due to stasis and slow flow.

in the portal and superior mesenteric veins, with calcification suggesting chronicity. Portal hypertension increases the risk of portal vein thrombus due to stasis and slow flow.TERMINOLOGY

Definitions

• Portal hypertension: Elevated portal pressures due to resistance to portal flow, defined as absolute portal venous pressure of > 10 mm Hg or gradient between portal and systemic veins of > 5 mm Hg

IMAGING

General Features

• Common features of portal hypertension

Varices: Well-defined, tubular or serpentine portosystemic collateral vessels with same enhancement as adjacent veins

Varices: Well-defined, tubular or serpentine portosystemic collateral vessels with same enhancement as adjacent veins

Slow or reversed flow in portal veins on Doppler ultrasound

Slow or reversed flow in portal veins on Doppler ultrasound

Varices: Well-defined, tubular or serpentine portosystemic collateral vessels with same enhancement as adjacent veins

Varices: Well-defined, tubular or serpentine portosystemic collateral vessels with same enhancement as adjacent veins

Slow or reversed flow in portal veins on Doppler ultrasound

Slow or reversed flow in portal veins on Doppler ultrasound

• Varices: Types or locations

Left gastric venous collateral vessels

Left gastric venous collateral vessels

Esophageal varices

Esophageal varices

Paraesophageal varices

Paraesophageal varices

Recanalized paraumbilical vein

Recanalized paraumbilical vein

Abdominal wall varices

Abdominal wall varices

Retrogastric varices

Retrogastric varices

Left gastric venous collateral vessels

Left gastric venous collateral vessels

Esophageal varices

Esophageal varices

– Dilated tortuous submucosal venous plexus of esophagus can be divided into “uphill” and “downhill” varices

Paraesophageal varices

Paraesophageal varices

Recanalized paraumbilical vein

Recanalized paraumbilical vein

Abdominal wall varices

Abdominal wall varices

Retrogastric varices

Retrogastric varices

PATHOLOGY

General Features

• Etiology

Causes of portal hypertension are divided into 3 categories

Causes of portal hypertension are divided into 3 categories

Blood flow always seeks path of least resistance and lowest pressure

Blood flow always seeks path of least resistance and lowest pressure

Causes of portal hypertension are divided into 3 categories

Causes of portal hypertension are divided into 3 categories

– Pre sinusoidal: Portal vein thrombosis, splenic vein thrombosis, compression of portal vein by tumor or lymphadenopathy, schistosomiasis

Blood flow always seeks path of least resistance and lowest pressure

Blood flow always seeks path of least resistance and lowest pressure

CLINICAL ISSUES

Presentation

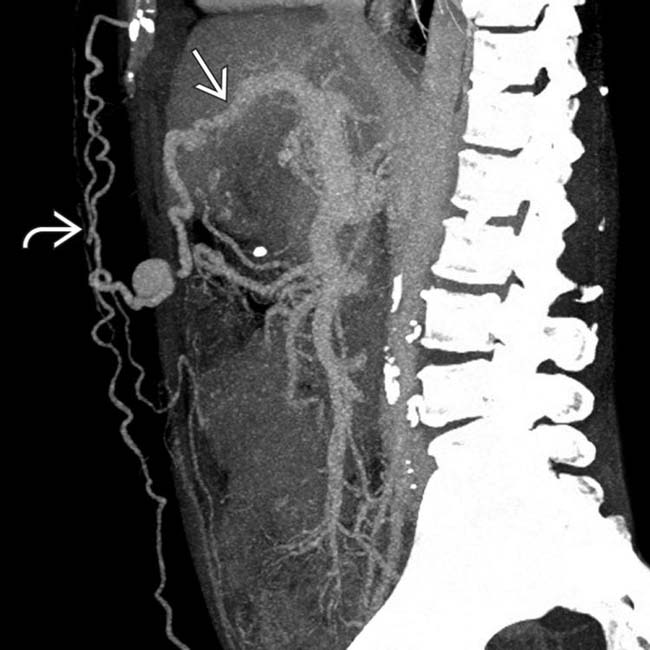

in communication with the left portal vein

in communication with the left portal vein  , a virtually pathognomonic finding for portal hypertension. Note the multiple periumbilical collaterals

, a virtually pathognomonic finding for portal hypertension. Note the multiple periumbilical collaterals  forming a caput medusae.

forming a caput medusae.

and multiple abdominal wall varices

and multiple abdominal wall varices  .

.

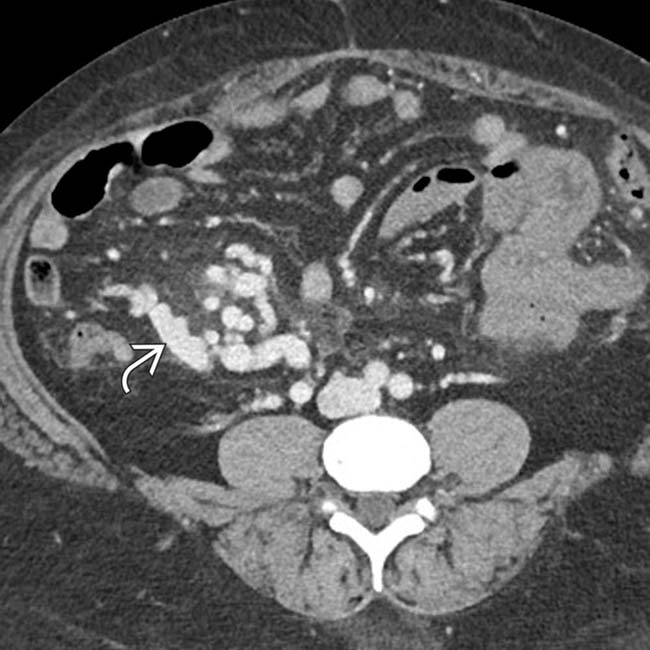

surrounding the rectum in a cirrhotic patient. While often asymptomatic, rectal varices (like varices elsewhere) can bleed and result in gastrointestinal hemorrhage.

surrounding the rectum in a cirrhotic patient. While often asymptomatic, rectal varices (like varices elsewhere) can bleed and result in gastrointestinal hemorrhage.

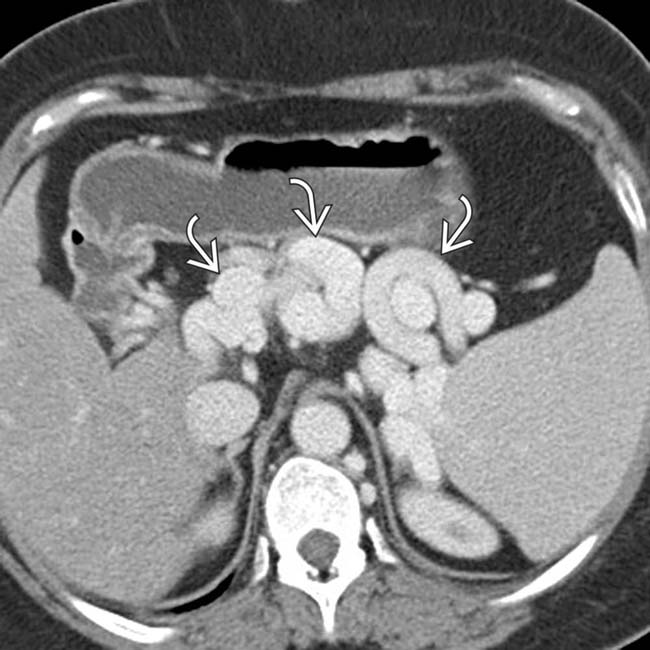

in the left upper quadrant. Although the diagnosis is straightforward on these venous phase images, the varices could mimic an intramural mass on NECT or arterial phase CECT images.

in the left upper quadrant. Although the diagnosis is straightforward on these venous phase images, the varices could mimic an intramural mass on NECT or arterial phase CECT images.

around the stoma. Surgical creation of the stoma creates a new site of portosystemic anastomosis and a potential site for the development of varices.

around the stoma. Surgical creation of the stoma creates a new site of portosystemic anastomosis and a potential site for the development of varices.

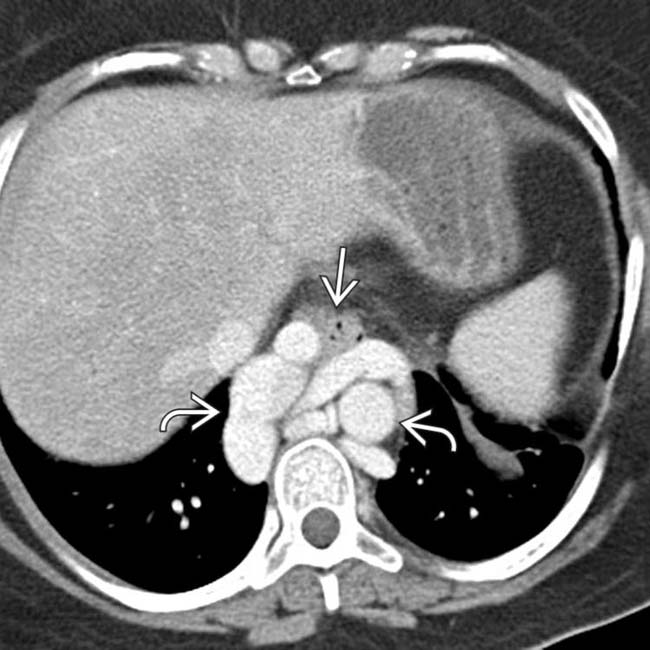

surrounding the esophagus

surrounding the esophagus  . Paraesophageal varices are not infrequently mistaken for a mediastinal mass on either CXR or NECT.

. Paraesophageal varices are not infrequently mistaken for a mediastinal mass on either CXR or NECT.

in the right lower quadrant.

in the right lower quadrant.

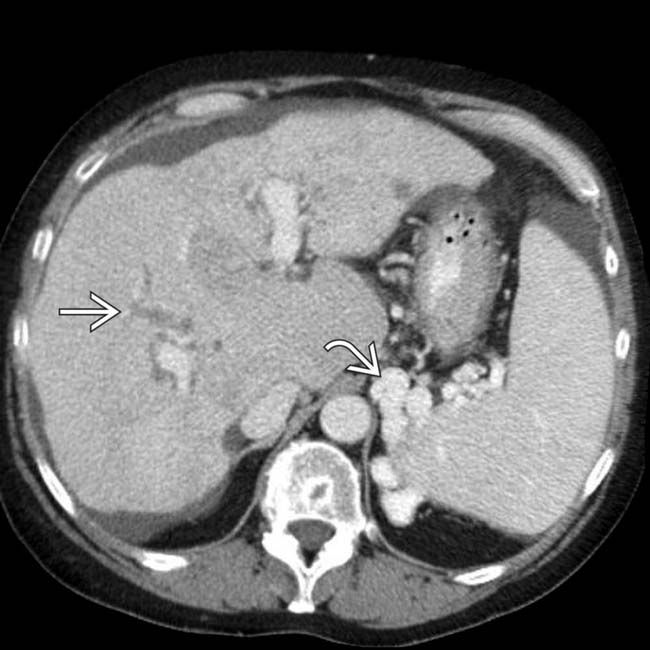

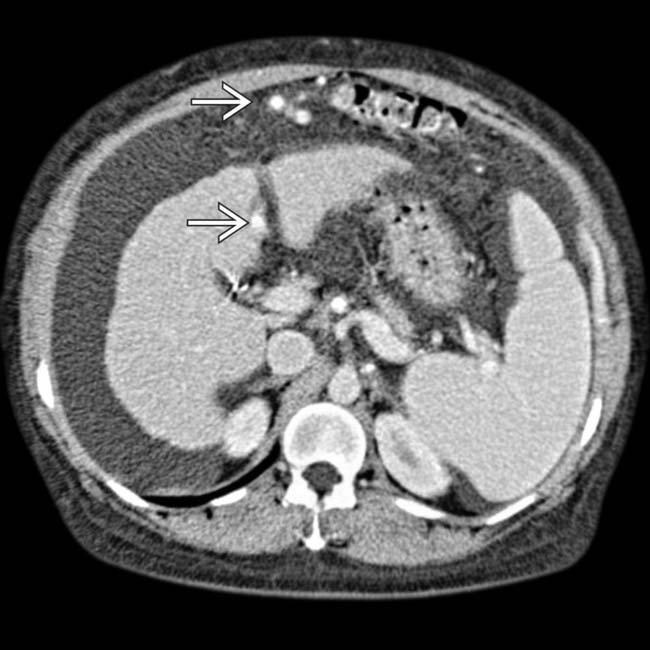

, and paraesophageal varices

, and paraesophageal varices  , a constellation of findings indicative of portal hypertension.

, a constellation of findings indicative of portal hypertension.

(caput medusae) in communication with a dilated recanalized paraumbilical vein

(caput medusae) in communication with a dilated recanalized paraumbilical vein  within the abdomen itself. These abdominal wall varices are frequently directly visible on clinical inspection.

within the abdomen itself. These abdominal wall varices are frequently directly visible on clinical inspection.

in the upper abdomen adjacent to the spleen and stomach.

in the upper abdomen adjacent to the spleen and stomach.

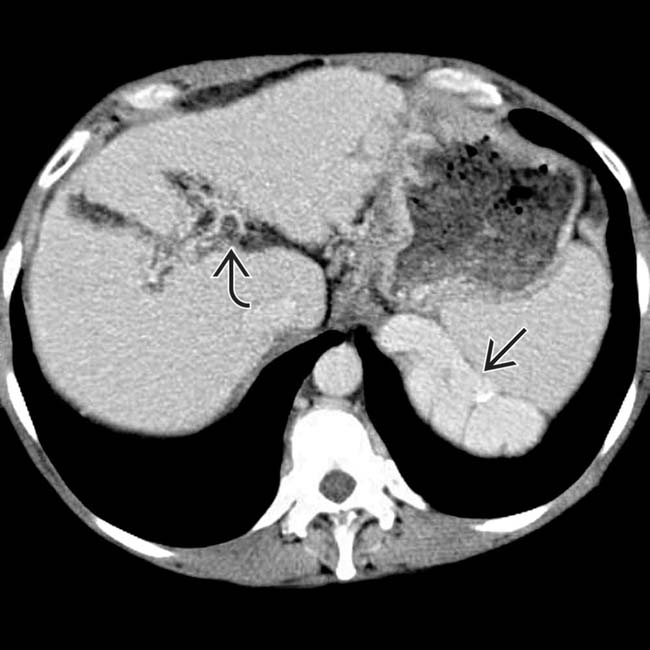

. The intrahepatic ducts

. The intrahepatic ducts  are dilated with an abnormal arborization, suggestive of primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). Biopsy showed elements of both PSC and autoimmune hepatitis.

are dilated with an abnormal arborization, suggestive of primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). Biopsy showed elements of both PSC and autoimmune hepatitis.

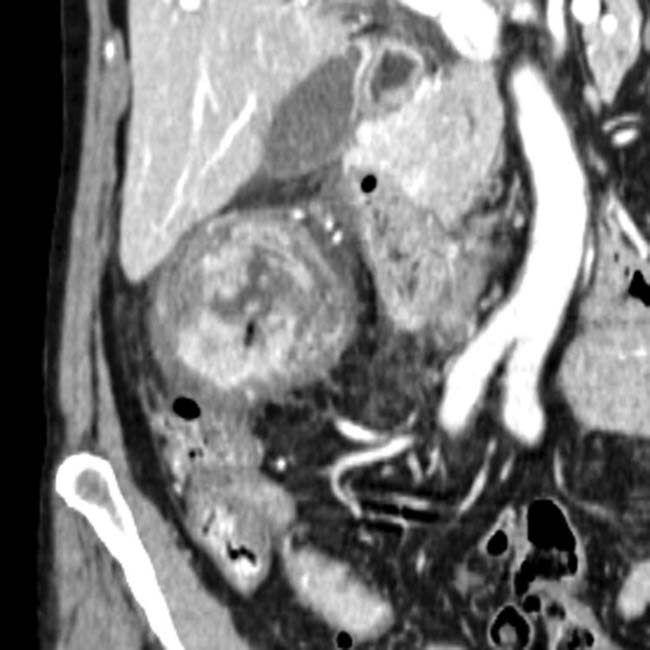

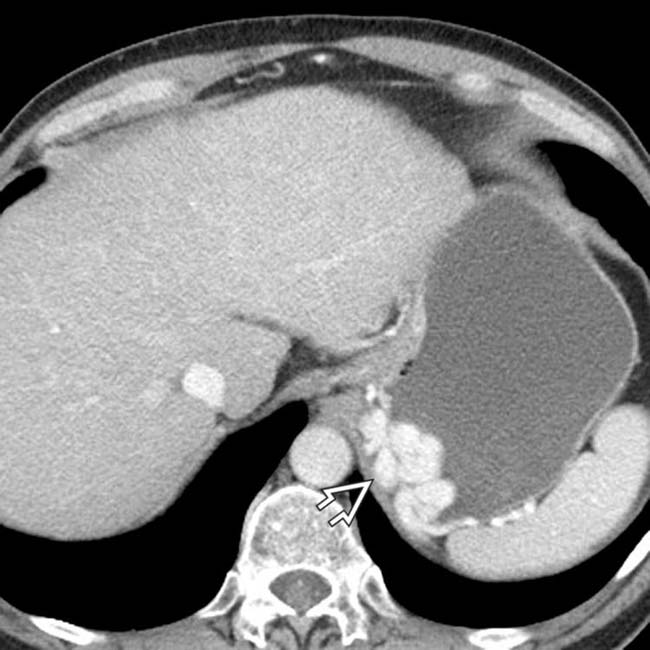

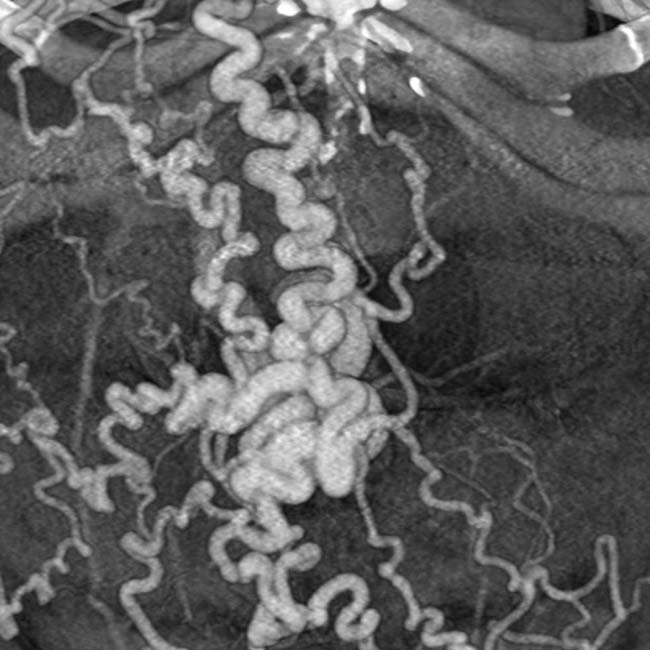

with cavernous transformation

with cavernous transformation  of the portal vein and extensive varices as a result.

of the portal vein and extensive varices as a result.

that might mimic primary gallbladder disease and the mass of varices in and around the pancreatic head

that might mimic primary gallbladder disease and the mass of varices in and around the pancreatic head  that might be mistaken for a hypervascular tumor of the pancreas. Gallbladder wall varices occur almost exclusively in patients with portal vein occlusion.

that might be mistaken for a hypervascular tumor of the pancreas. Gallbladder wall varices occur almost exclusively in patients with portal vein occlusion.

, which simulates findings seen with colitis. On colonoscopy, there was no mucosal inflammation, only venous engorgement, known as portal hypertensive colopathy.

, which simulates findings seen with colitis. On colonoscopy, there was no mucosal inflammation, only venous engorgement, known as portal hypertensive colopathy.

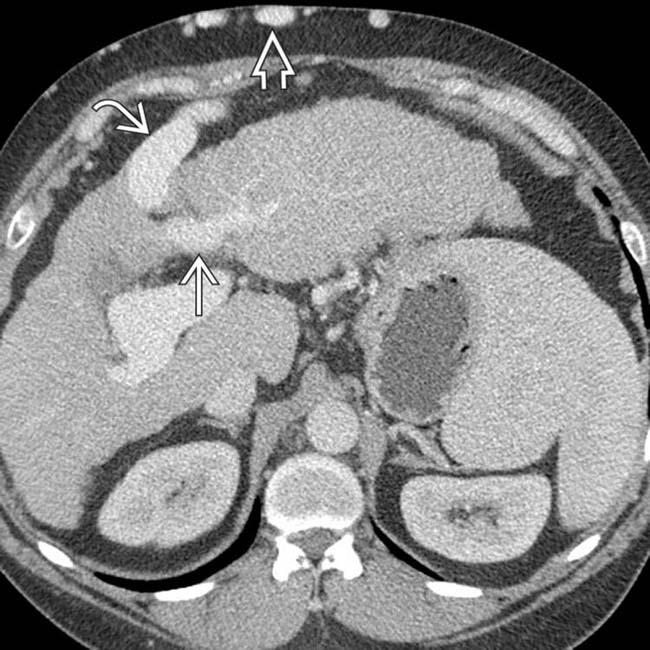

. The liver has a cirrhotic morphology with widened fissures and an increased caudate to right lobe ratio.

. The liver has a cirrhotic morphology with widened fissures and an increased caudate to right lobe ratio.

in a patient with cirrhosis and severe portal hypertension.

in a patient with cirrhosis and severe portal hypertension.

, a cirrhotic liver, and huge upper abdominal varices

, a cirrhotic liver, and huge upper abdominal varices  .

.

that represents active bleeding from gastric varices (no oral contrast was given). Variceal bleeding is one of the leading causes of death among patients with cirrhosis.

that represents active bleeding from gastric varices (no oral contrast was given). Variceal bleeding is one of the leading causes of death among patients with cirrhosis.

. The collateral vessels continued caudally to surround the umbilicus where parumbilical varices were seen (not shown).

. The collateral vessels continued caudally to surround the umbilicus where parumbilical varices were seen (not shown).