Polyps of the Stomach

Jerrold R. Turner

Robert D. Odze

Introduction

Gastric polyps are identified in as many as 6.3% of upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopic procedures.1–7 Polyps may develop as a result of epithelial or stromal cell hyperplasia, inflammation, ectopia, or neoplasia. This chapter classifies gastric polyps according to the predominant cell type (e.g., epithelial, lymphoid, mesenchymal) responsible for polyp growth (Box 20.1).

The importance of clinicopathologic correlation in the evaluation of gastric polyps cannot be overstated. Anatomic location, endoscopic appearance, number of lesions, and the presence or absence of pathology in the surrounding gastric mucosa provide essential information for the proper classification and etiologic determination of gastric polyps. For example, biopsies obtained from tissue adjacent to an ulcer may show an expanded lamina propria, foveolar hyperplasia, and marked regenerative changes that can mimic a hyperplastic polyp or an adenoma and that can lead to an incorrect diagnosis if the endoscopic findings are unknown. Incomplete endoscopic resection of gastric polyps has been suggested to result in a misdiagnosis in up to 50% of cases.8–10

Hyperplastic Polyps

Clinical Features and Pathogenesis

Numerous synonyms, including inflammatory polyp, regenerative polyp, and hyperplasiogenous polyp, have been used to describe hyperplastic polyps. The diversity of names is not surprising given the prevalence and pathologic diversity of these lesions. Hyperplastic polyps account for approximately 75% of all gastric polyps.1,11–14

Hyperplastic polyps are detected most often in older patients, with a peak incidence occurring in the sixth and seventh decades of life,1 and they are diagnosed equally in both genders.15–20 Because they most often appear in the context of chronic gastritis, hyperplastic polyps are associated with clinical symptoms and signs similar to those in patients with chronic gastritis. In many cases, patients are asymptomatic. Rarely, large lesions can cause obstructive symptoms if located near the pylorus or gastroesophageal junction. Helicobacter pylori infection is common.

More than 85% of hyperplastic polyps occur in a background of chronic gastritis,13–15 and this observation has led some to conclude that the lesions develop as a consequence of an exaggerated mucosal response to tissue injury and inflammation.15,21,22 It is thought that gastritis initiates the process of injury and that the mucosal healing response results in a stepwise progression through phases of foveolar hyperplasia and polypoid foveolar hyperplasia to the formation of a hyperplastic polyp.

Conditions associated with the development of hyperplastic polyps include H. pylori gastritis, chronic non–H. pylori gastritis, chemical or reactive gastritis (including gastritis caused by bile reflux), and gastritis related to Billroth II gastrectomy.1,15–17,23 The H. pylori CagA protein may have a more direct role, because expression of CagA in the gastric mucosa of transgenic mice produces hyperplastic polyps.1,24 The tendency of hyperplastic polyps to occur more proximally in the stomach in the setting of autoimmune gastritis (which involves the corpus of the stomach) than in other types of gastritis15 supports the hypothesis that hyperplastic polyps develop as a consequence of chronic mucosal injury.

In one study, 33% of hyperplastic polyps of the gastroesophageal junction were related to Barrett’s esophagus, and they presumably developed in the context of reflux.25 In other instances, a hyperplastic polyp may be the first biopsy finding that leads to a diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus.25 One study22 suggests that many so-called hyperplastic polyps (as many as 49%) instead represent foveolar hyperplasia resulting from a lack of significant stromal edema or inflammatory changes, cyst formation, muscle hyperplasia, or large-sized vessels. In that study, 51% of originally diagnosed hyperplastic polyps were reclassified as mucosal prolapse polyps. They occurred more commonly in the antral or prepyloric region of the stomach and showed thickened and hyperplastic-appearing bands of muscle extending toward the surface of the polyp and thick-walled blood vessels, both of which are characteristic of prolapse-type polyps in other areas of the GI tract.

Pathologic Features

Almost 50% of hyperplastic polyps are less than 0.5 cm in greatest dimension at the time of diagnosis; most are smaller than 1 cm. However, lesions may rarely grow to as large as 12 cm. Large polyps can easily be misdiagnosed clinically and pathologically as carcinomas. All hyperplastic polyps should be exhaustively sampled and the entire polyp submitted for histologic evaluation.

Hyperplastic polyps occur most commonly in the antrum, but they can be found anywhere in the stomach.20 They may develop as solitary lesions but frequently occur as multiple polyps, particularly in patients with atrophic gastritis. In some studies, fundic gland polyps have been associated with as much as a 7% incidence of hyperplastic polyps.1 These data may reflect a link between hyperplastic polyps and gastritis, the frequent use of proton pump inhibitors in chronic gastritis, and an association between proton pump inhibitors and fundic gland polyps.

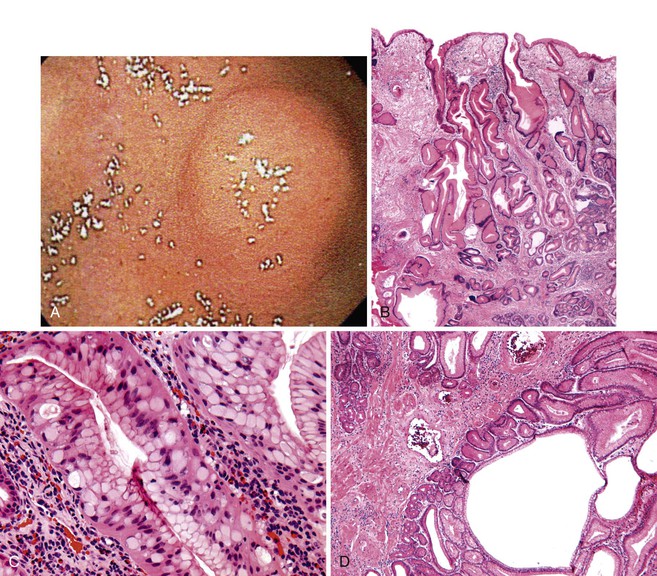

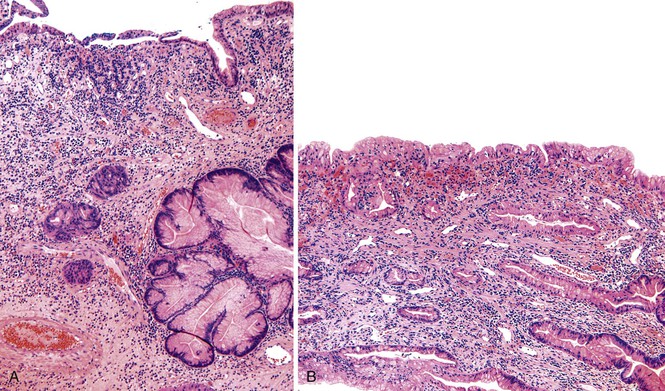

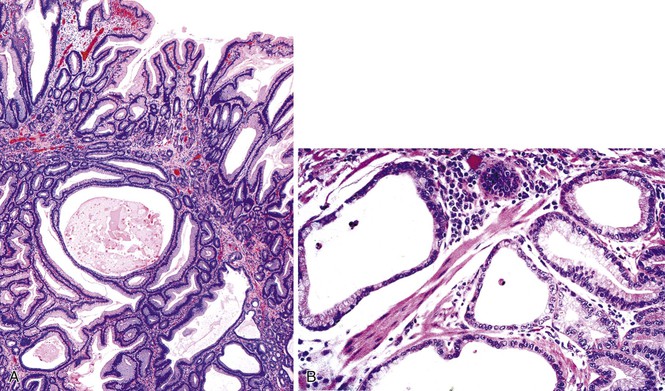

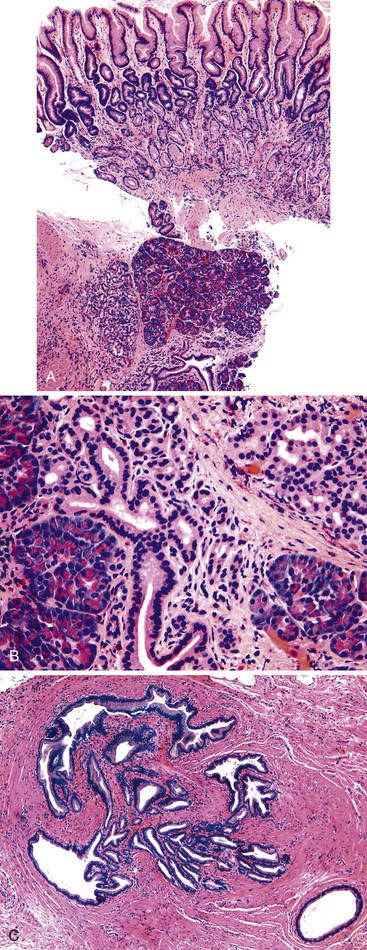

Grossly, hyperplastic polyps are typically ovoid and contain a smooth surface contour, although villiform or pedunculated polyps may develop (Fig. 20.1, A). Surface erosion is often seen. Rarely, patients may have more than 50 polyps, in which case a diagnosis of gastric hyperplastic polyposis should be considered, although specific diagnostic criteria for this syndrome have not been well established.26–28 In this situation, pathologists should obtain further clinical and endoscopic information to rule out another type of polyposis disorder, such as juvenile polyposis, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, or familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP).

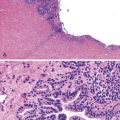

Microscopically, hyperplastic polyps are characterized by architecturally distorted, irregular, cystically dilated, and elongated foveolar epithelium (see Fig. 20.1, B). Intestinal metaplasia (i.e., goblet cells) may be identified, particularly in polyps located at the gastroesophageal junction and associated with Barrett’s esophagus. Crowding of cells and infolding of the epithelium often impart a corkscrew appearance. Foveolar cells typically have abundant mucinous cytoplasm, but they may be mucin depleted focally and contain slightly enlarged and hyperchromatic nuclei with prominent nucleoli, which are considered to be regenerative features. Mitotic activity may be brisk in areas of active inflammation and surface ulceration.

Pseudogoblet or globoid mucinous cells, which are frequently seen, are cells that contain apically located nuclei and basally oriented mucous vacuoles (see Fig. 20.1, C). These cells were considered to be dysplastic before they were recognized as a reactive change. Therefore, previously used term globoid dysplasia has been discarded in favor of the more descriptive term dystrophic goblet cell. Intestinal metaplasia is identified in less than 25% of hyperplastic polyps and, paradoxically, is more often seen in the surrounding nonpolypoid mucosa than in the polyp itself. The lamina propria of hyperplastic polyps is typically edematous and congested, with various degrees of acute and chronic inflammation and smooth muscle consistent with prolapse (see Fig. 20.1, D). The inflammatory infiltrate is usually most prominent in the superficial aspects of the polyp and is often associated with surface erosions (see Fig. 20.1, E). In rare cases, granulation tissue associated with ulcerations (see Fig. 20.1, F) may show marked atypical pseudosarcomatous changes in reactive stromal fibroblasts and endothelial cells (see Fig. 20.1, G).

Nodular lymphoid aggregates, with or without germinal centers, may be seen in gastric hyperplastic polyps. Most well-developed hyperplastic polyps also contain thick or thin, wispy bundles of smooth muscle that extend upward from the muscularis mucosae toward the polyp surface and have large, thick-walled blood vessels at the base of the polyp, which may indicate prolapse as a pathogenic factor. These polyps tend to occur in the antral or prepyloric region of the stomach. As noted above, H. pylori infection is common, and organisms are found in as many as 76% of hyperplastic polyps.15,29

Differential Diagnosis

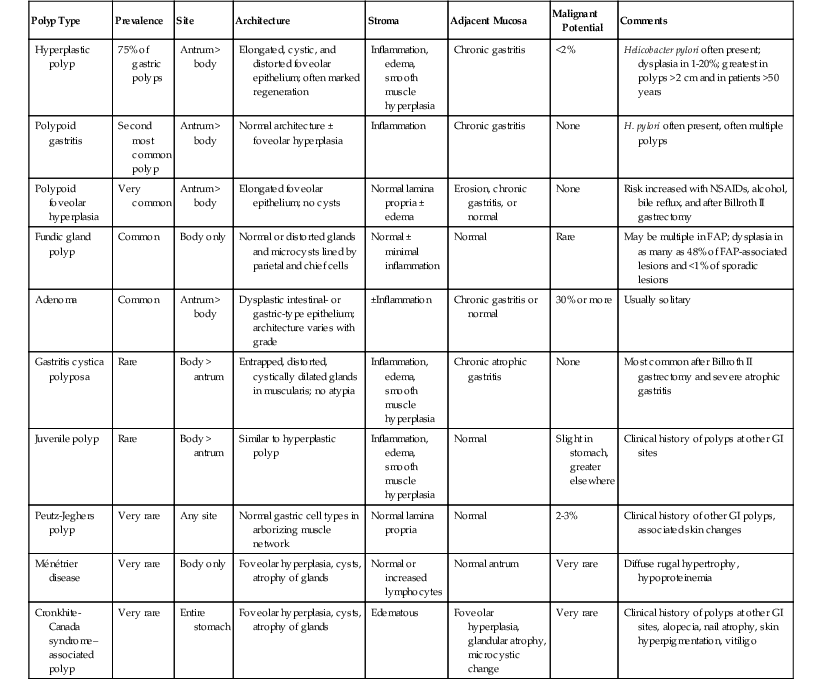

The differential diagnosis of gastric hyperplastic polyps includes polypoid gastritis, polypoid foveolar hyperplasia, gastritis cystica polyposa or profunda, fundic gland polyps, polyps associated with Ménétrier disease, Cronkhite-Canada syndrome, juvenile polyposis, and Peutz-Jeghers polyposis. Features helpful in determining the correct diagnosis are summarized in Table 20.1. Polyps in patients with polypoid gastritis and polypoid foveolar hyperplasia are typically smaller than hyperplastic polyps, and they lack cystically dilated, irregular, and tortuous foveolar epithelium. The lamina propria of polypoid foveolar hyperplasia contains less inflammation and lacks smooth muscle hyperplasia.

Table 20.1

Features of Gastric Polyps

| Polyp Type | Prevalence | Site | Architecture | Stroma | Adjacent Mucosa | Malignant Potential | Comments |

| Hyperplastic polyp | 75% of gastric polyps | Antrum > body | Elongated, cystic, and distorted foveolar epithelium; often marked regeneration | Inflammation, edema, smooth muscle hyperplasia | Chronic gastritis | <2% | Helicobacter pylori often present; dysplasia in 1-20%; greatest in polyps >2 cm and in patients >50 years |

| Polypoid gastritis | Second most common polyp | Antrum > body | Normal architecture ± foveolar hyperplasia | Inflammation | Chronic gastritis | None | H. pylori often present, often multiple polyps |

| Polypoid foveolar hyperplasia | Very common | Antrum > body | Elongated foveolar epithelium; no cysts | Normal lamina propria ± edema | Erosion, chronic gastritis, or normal | None | Risk increased with NSAIDs, alcohol, bile reflux, and after Billroth II gastrectomy |

| Fundic gland polyp | Common | Body only | Normal or distorted glands and microcysts lined by parietal and chief cells | Normal ± minimal inflammation | Normal | Rare | May be multiple in FAP; dysplasia in as many as 48% of FAP-associated lesions and <1% of sporadic lesions |

| Adenoma | Common | Antrum > body | Dysplastic intestinal- or gastric-type epithelium; architecture varies with grade | ±Inflammation | Chronic gastritis or normal | 30% or more | Usually solitary |

| Gastritis cystica polyposa | Rare | Body > antrum | Entrapped, distorted, cystically dilated glands in muscularis; no atypia | Inflammation, edema, smooth muscle hyperplasia | Chronic atrophic gastritis | None | Most common after Billroth II gastrectomy and severe atrophic gastritis |

| Juvenile polyp | Rare | Body > antrum | Similar to hyperplastic polyp | Inflammation, edema, smooth muscle hyperplasia | Normal | Slight in stomach, greater elsewhere | Clinical history of polyps at other GI sites |

| Peutz-Jeghers polyp | Very rare | Any site | Normal gastric cell types in arborizing muscle network | Normal lamina propria | Normal | 2-3% | Clinical history of other GI polyps, associated skin changes |

| Ménétrier disease | Very rare | Body only | Foveolar hyperplasia, cysts, atrophy of glands | Normal or increased lymphocytes | Normal antrum | Very rare | Diffuse rugal hypertrophy, hypoproteinemia |

| Cronkhite-Canada syndrome–associated polyp | Very rare | Entire stomach | Foveolar hyperplasia, cysts, atrophy of glands | Edematous | Foveolar hyperplasia, glandular atrophy, microcystic change | Very rare | Clinical history of polyps at other GI sites, alopecia, nail atrophy, skin hyperpigmentation, vitiligo |

FAP, Familial adenomatous polyposis; GI, gastrointestinal; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs; ±, with or without.

Gastritis cystica polyposa or profunda is closely related to hyperplastic polyps in its pathogenesis and morphologic appearance (see Gastritis Cystica Polyposa or Profunda). The surface and intraluminal portions of these lesions may be identical. However, unlike hyperplastic polyps, gastritis cystica polyposa is characterized by cystically dilated, distorted, and irregularly shaped glands or acellular mucin pools located in the muscularis mucosae or the submucosa. Polyps related to gastritis cystica polyposa often develop adjacent to anastamotic sites in patients who have had a partial gastrectomy.

In contrast to hyperplastic polyps, fundic gland polyps show surface and foveolar hypoplasia and contain cystically dilated glands lined predominantly by parietal and chief cells. Occasional cysts may contain mucous cells. Fundic gland polyps do not normally contain prominent inflammation, ulceration, or marked regenerative changes typical of hyperplastic polyps.

Polyps associated with Ménétrier disease, Cronkhite-Canada syndrome, and juvenile polyps are histologically similar to hyperplastic polyps. Appropriate clinical and endoscopic information is essential to establish a correct diagnosis.30

Examination of Peutz-Jeghers polyps of the stomach may reveal a characteristic arborizing pattern of smooth muscle that is more extensive than that of hyperplastic polyps. Peutz-Jeghers polyps also lack significant stromal inflammation and are usually not associated with underlying chronic gastritis. However, other features of Peutz-Jeghers polyps are similar to those of hyperplastic polyps.

Natural History and Treatment

The natural history of hyperplastic polyps is poorly understood, but some data suggest that as many as 67% remain stable, 27% may enlarge, and 5% shrink with time.31,32 Recurrent polyps develop in as many as 50% of patients after endoscopic resection.33,34 Conversely, regression of hyperplastic polyps has been documented in as many as 71% of patients with H. pylori infection after eradication of the bacteria.29,35,36 Because of the risk of dysplasia in larger polyps, resection is recommended for all polyps greater than 1.5 cm in the largest dimension.

Dysplasia and Cancer in Hyperplastic Polyps

The incidence of dysplasia in hyperplastic polyps ranges from 1% to 20%.15,37–43 Although universal agreement has not been reached, it appears that the risk of dysplasia is related to polyp size; it occurs rarely in polyps smaller than 1.5 cm in diameter. The risk of dysplasia increases progressively in polyps that exceed 2 cm. Age is also a risk factor.

Dysplasia- and carcinoma-containing hyperplastic polyps tend to occur in patients older than 50 years. Carcinoma is uncommon in hyperplastic polyps, but when present it is thought to develop from dysplastic epithelium. Some data suggest that TP53 mutations, chromosomal loss, and chromosomal amplification may be important in the development of dysplasia and carcinoma in gastric hyperplastic polyps, but further work is needed to better define the molecular biology of neoplastic transformation in these lesions.44–48

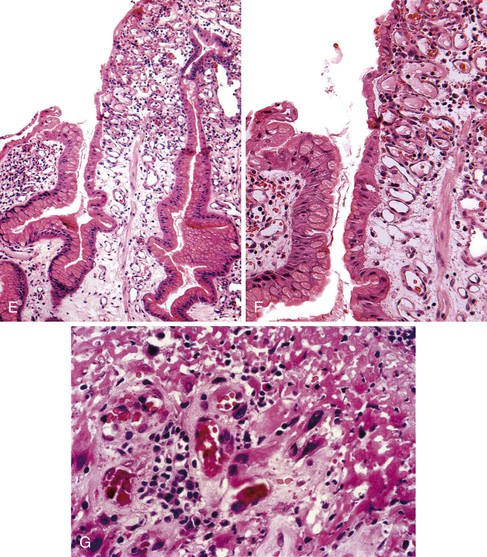

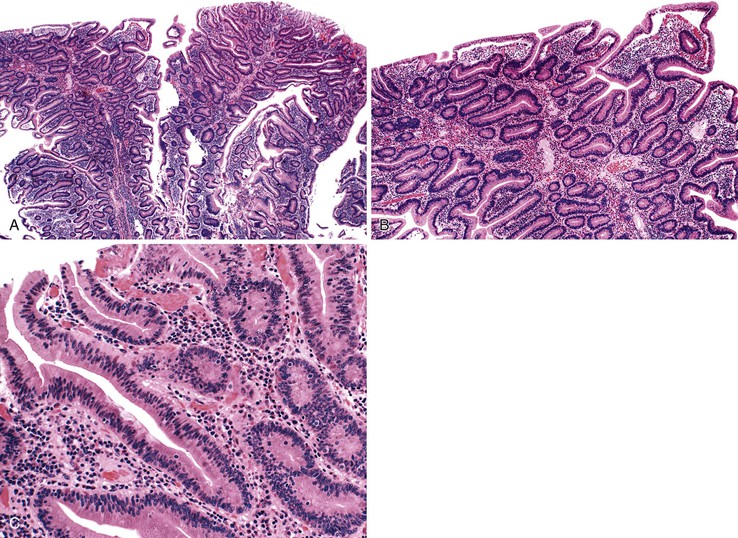

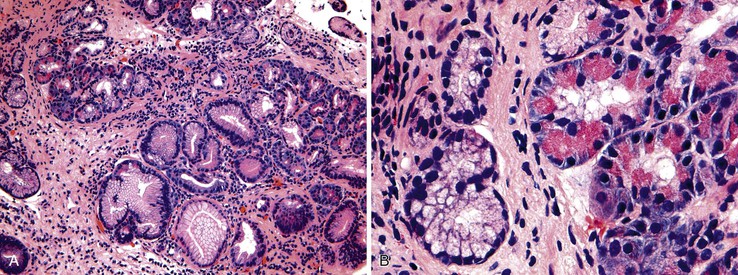

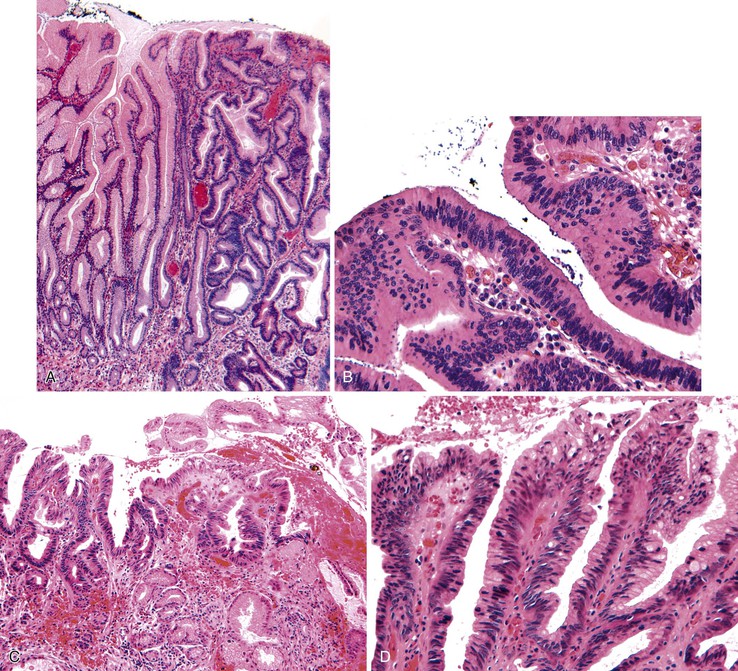

The microscopic appearance of dysplasia in hyperplastic polyps is similar to that in other areas of the GI tract and is categorized as low or high grade. Dysplasia may be intestinal (adenomatous), foveolar, serrated (rarely), or mixed (Fig. 20.2). In intestinal-type, low-grade dysplasia, the epithelium is composed of cells with hyperchromatic and elongated nuclei, clumped chromatin, and pseudostratification. Multiple nucleoli can occur. These changes almost always involve the surface epithelium and may involve the deep glands. Polyps without dysplasia on the surface are rare and may reflect surface erosion rather than lack of involvement.

Mitotic activity is often brisk, and nuclei may show atypia, particularly in cells at the surface of the polyp. High-grade dysplasia is characterized by a greater degree of nuclear pleomorphism, loss of cell polarity, and abundant abnormal mitoses. Architectural distortion of the epithelium may also occur in the form of back-to-back gland formation and full-thickness nuclear stratification. Overall, the architecture is complex, with the formation of cribriform profiles and tubular budding. Features of cellular differentiation, such as cytoplasmic mucin, are progressively lost in high-grade dysplasia.

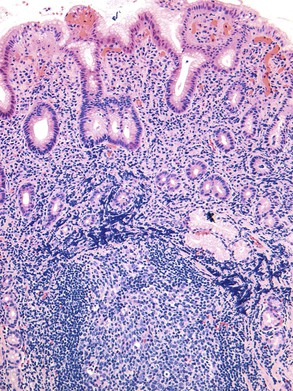

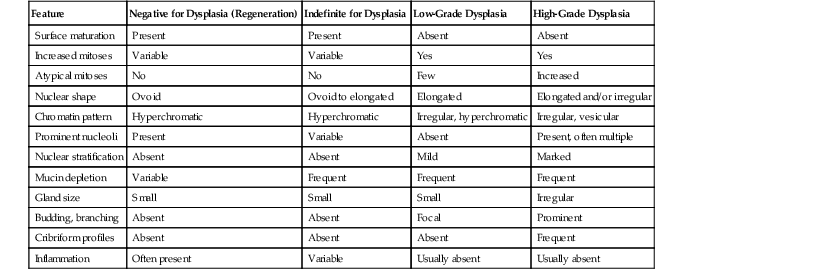

The principle differential diagnosis of a hyperplastic polyp with dysplasia is a polyp with marked regeneration (Table 20.2). The single most useful feature for distinguishing these lesions is nuclear atypia at the surface of polyps with dysplasia but an absence of surface atypia in regenerating lesions. Cytologic atypia limited to the deeper proliferative zones in the polyp with some degree of surface maturation is more often regenerative than dysplastic (Fig. 20.3). A diagnosis of dysplasia limited to proliferative zones should not be considered unless there is significant nuclear pleomorphism or loss of cell polarity, or both, in an area of the polyp without active inflammation. In the setting of active inflammation, the degree of atypia may be marked, and a diagnosis of dysplasia should be made with great caution. Nuclear pleomorphism and loss of cell polarity, particularly in the absence of prominent nucleoli, favor a diagnosis of dysplasia. Architectural aberration, such as a cribriform growth pattern, suggests dysplasia. An abrupt change in the degree of epithelial atypia in areas away from active inflammation strongly favors a diagnosis of dysplasia.

Table 20.2

Differentiation of Dysplasia from Regeneration in Gastric Polyps

| Feature | Negative for Dysplasia (Regeneration) | Indefinite for Dysplasia | Low-Grade Dysplasia | High-Grade Dysplasia |

| Surface maturation | Present | Present | Absent | Absent |

| Increased mitoses | Variable | Variable | Yes | Yes |

| Atypical mitoses | No | No | Few | Increased |

| Nuclear shape | Ovoid | Ovoid to elongated | Elongated | Elongated and/or irregular |

| Chromatin pattern | Hyperchromatic | Hyperchromatic | Irregular, hyperchromatic | Irregular, vesicular |

| Prominent nucleoli | Present | Variable | Absent | Present, often multiple |

| Nuclear stratification | Absent | Absent | Mild | Marked |

| Mucin depletion | Variable | Frequent | Frequent | Frequent |

| Gland size | Small | Small | Small | Irregular |

| Budding, branching | Absent | Absent | Focal | Prominent |

| Cribriform profiles | Absent | Absent | Absent | Frequent |

| Inflammation | Often present | Variable | Usually absent | Usually absent |

Hyperplastic polyps with dysplasia should be differentiated from gastric adenomas. Adenomas are characterized by the absence of adjacent or underlying hyperplastic foveolar epithelium, cystic change, and inflammatory stroma, all of which are characteristic of hyperplastic polyps.

Morphologic Variants

Polypoid Foveolar Hyperplasia

Polypoid foveolar hyperplasia is regarded as a precursor of hyperplastic polyps.22 Similar to hyperplastic polyps, polypoid foveolar hyperplasia is a regenerative lesion associated with chronic gastritis and with other types of acute and chronic mucosal injury.14 For example, polypoid foveolar hyperplasia often develops at the mucosal edges of surface erosions, ulcers, and carcinomas or adjacent to gastrojejunostomy stomas. It may also be associated with the use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, bile reflux, alcohol use, or cytomegalovirus infection.33,34,49,50 Polypoid foveolar hyperplasia may remain stable in size, regress, or grow. The proportion of these lesions that ultimately progress to hyperplastic polyps is unknown.

Grossly, polypoid foveolar hyperplasia usually appears as a sessile lesion that is 1 to 2 mm in diameter. Lesions may be single or multiple and are most often found in the antrum. Microscopically, polypoid foveolar hyperplasia is characterized by simple hyperplasia of the gastric foveolar epithelium without cystic change or significant distortion. The foveolar epithelium is increased in length, and luminal serration imparts a corkscrew-like pattern (Fig. 20.4). The foveolae are typically crowded and tightly packed, containing little intervening stroma. The epithelium is often mucin depleted and reactive in appearance, with mitotic figures, enlarged nuclei, and prominent nucleoli. Various degrees of intestinal metaplasia may be seen. Examination of the lamina propria may reveal a mild lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, but smooth muscle proliferation is typically absent unless there is associated bile reflux.

Gastric Foveolar Polyps

Gastric foveolar polyps were originally described by Goldman and Appelman in 1972.51 It is unclear whether they represent regenerative lesions, a subtype of hyperplastic polyp, or a hamartomatous proliferation. Some lesions resemble pyloric gland adenomas. A foveolar polyp is not universally accepted as a separate polyp type, perhaps because foveolar hyperplasia occurs so frequently in other reactive lesions.

Foveolar polyps are found primarily in the antrum and are usually smaller than 2 cm in diameter.51 However, some can reach sizes of as great as 8 cm.19 They are composed of densely packed foveolar mucinous epithelium that forms an arborizing network. Intestinal metaplasia is observed in approximately 33% of cases. Inflammation is conspicuously absent. Of the eight patients originally described,51 one had coexisting gastric carcinoma and a second had colonic carcinoma. Other rare reports of dysplasia do exist,43 but foveolar polyps are not thought to be associated with an increased risk of malignancy. Foveolar polyps can be differentiated from hyperplastic polyps and polypoid foveolar hyperplasia by the absence of an inflammatory infiltrate and cystic change.

Gastritis Cystica Polyposa or Profunda

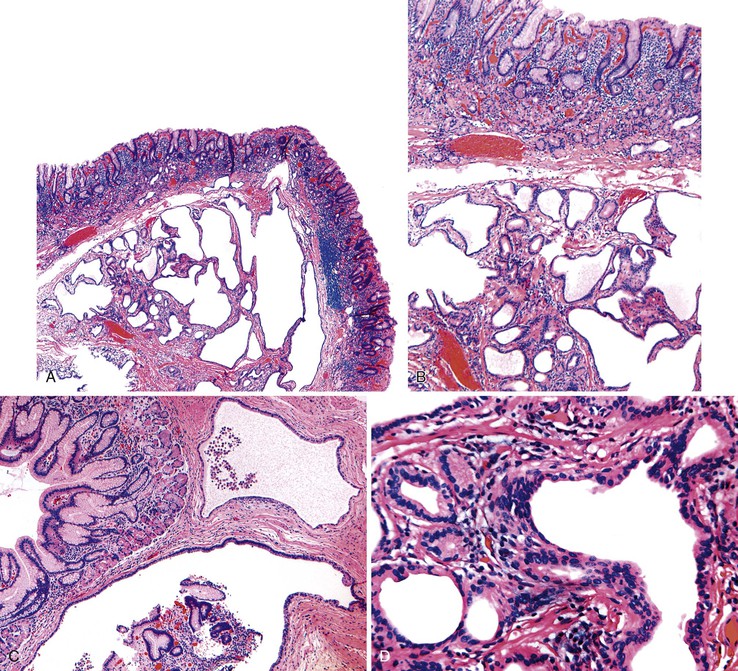

Gastritis cystica polyposa or profunda is defined as a hyperplastic polyp that contains foci of misplaced foveolar or glandular epithelium, or both, in the muscularis mucosae or in deeper portions of the submucosa, muscularis propria, or serosa. The lesion is referred to as polyposa when an intraluminal polyp is identified and as profunda when the bulk of the lesion is located in the wall of the stomach; both forms may result in gastric bleeding.52–54

Although these lesions may develop in surgically naive stomachs, they more often occur in patients with partial gastrectomy-induced chronic bile reflux or surgical or endoscopic manipulation.54–61 Gastritis cystica polyposa can be referred to as stromal polypoid hypertrophic gastritis when it occurs in a postoperative gastric remnant. Because of the association with chronic gastritis and partial gastrectomy, it is presumed that gastritis cystica polyposa or profunda is caused by an exuberant reactive proliferation with trauma-induced entrapment of epithelium in deep portions of the gastric wall. However, the reasons for the development of epithelial cysts in deeper portions of the gastric wall are not clear. Some have suggested that local ischemia and mucosal prolapse are critical to the development of submucosal or mural cysts.

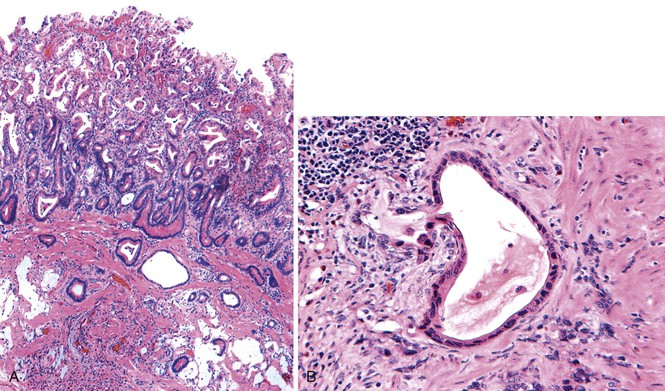

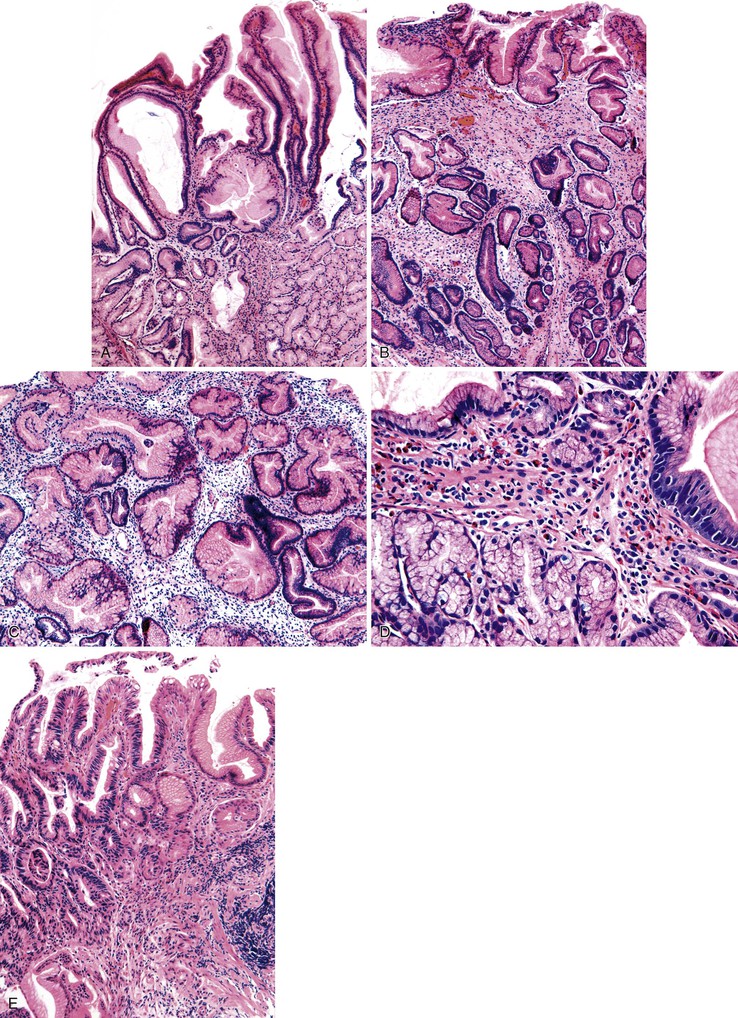

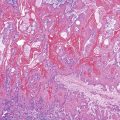

Pathologically, polyps of gastritis cystica polyposa or profunda are usually located on the gastric side of gastroenteric anastomoses. Rarely, they develop on a background of chronic gastritis and are grossly indistinguishable from hyperplastic polyps. Lesions may reach as great as 3 cm in diameter and are often associated with enlarged rugal folds. The characteristic histologic feature is entrapped epithelium or glands in or beneath the muscularis mucosae of the polyp (Fig. 20.5). The epithelium may be mucinous or glandular, is often cystic, and is usually surrounded by a rim of lamina propria–like stroma. The cysts are usually entrapped in dense, disorganized bundles of smooth muscle that extend downward from the muscularis mucosae. Marked hyperplasia, reactive changes, and mucin depletion impart an atrophic appearance to the epithelium. An associated inflammatory infiltrate, composed of neutrophils and mononuclear cells, may be found in the lamina propria. Superficial erosion and intestinal metaplasia may also occur. Dysplasia and cancer rarely develop in association with gastritis cystica polyposa or profunda,62 and it is unclear whether the frequency of occurrence is equal to or greater than that of ordinary hyperplastic polyps.

It is sometimes difficult to distinguish misplaced epithelium in gastritis cystica polyposa or profunda from a well-differentiated invasive adenocarcinoma (Fig. 20.6).63,64 Features such as desmoplasia, cytologic pleomorphism, irregularity in the size and shape of the glands, atypical mitoses, and lack of a lamina propria rim surrounding the epithelium favor a diagnosis of adenocarcinoma (Table 20.3).

Table 20.3

Differentiation between Gastritis Cystica Polyposa or Profunda and Invasive Adenocarcinoma

| Feature | Gastritis Cystica Polyposa or Profunda | Invasive Adenocarcinoma |

| Overlying hyperplastic polyp | Yes | No |

| Overlying dysplasia | No | Frequent |

| Inflammation | Prominent | Absent |

| Smooth, lobular gland profiles | Yes | No |

| Irregular, distorted glands | No | Yes |

| Wide variation in size and shape of glands | No | Yes |

| Rim of lamina propria surrounding glands | Usually | Never |

| Mitoses | Rare | Common |

| Stromal desmoplasia | No | Often |

| Intraluminal necrosis | No | Occasional |

| Deep (muscularis propria or serosal) penetration | Rare | Not uncommon |

Ménétrier Disease

Clinical Features

Ménétrier disease is a rare disorder characterized by diffuse hyperplasia of the foveolar epithelium of the body and fundus combined with hypoproteinemia resulting from protein-losing enteropathy. Other symptoms include weight loss, diarrhea, and peripheral edema. In rare (mostly pediatric) cases, the antrum may be involved. In adults, onset typically occurs between 30 and 60 years of age, with a male-to-female ratio of 3 to 1.65,66

Although the clinical and pathologic features of Ménétrier disease in children are similar to those in adults, many children have a history of recent respiratory infection, peripheral blood eosinophilia, and cytomegalovirus infection.67 The disease is usually self-limited in children, lasting only several weeks.68,69 In contrast, adult Ménétrier disease is unlikely to regress.

Pathogenesis

Ménétrier disease is a form of hyperplastic gastropathy that in many cases is driven by excessive secretion of transforming growth factor-α (TGF-α).70 In children, some cases are associated with cytomegalovirus or other types of infections.50,67,71 In these cases, spontaneous and treatment-associated remissions may occur. Although H. pylori infection and various other conditions have been associated with Ménétrier disease in adults, antibiotics, acid suppression, octreotide, and anticholinergic agents have had therapeutic benefit in rare adult patients.72–74 In contrast, inhibition of TGF-α signaling has been effective in some cases.75

Pathologic Features

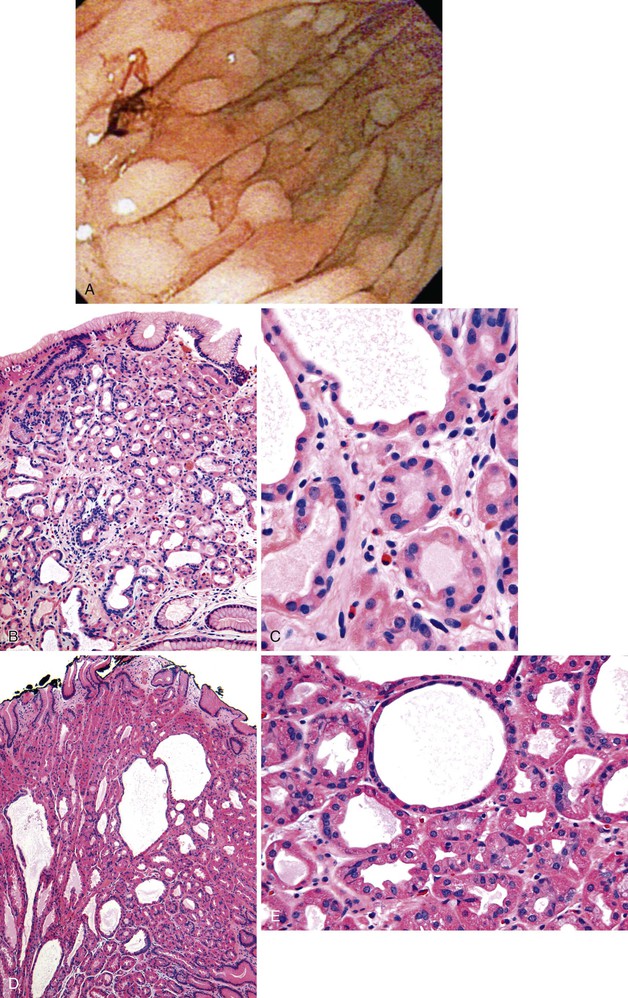

On endoscopic examination, Ménétrier disease is characterized by diffuse, irregular enlargement of the gastric rugae. However, some areas may appear polypoid.76,77 Enlarged rugae typically involve the body and fundus, but they may also involve the antrum, particularly in children.30,78 Histologically, the most characteristic feature of Ménétrier disease is foveolar (mucous cell) hyperplasia (Fig. 20.7). The foveolae are elongated and have a corkscrew appearance. Cystic dilation is also common. Hyperplastic mucous cells are typically fully differentiated without regenerative features or mucin depletion. Inflammation is usually only modest, and ulceration is not normally identified. Intestinal metaplasia is usually absent. Some cases show marked intraepithelial lymphocytosis. Diffuse or patchy glandular atrophy and hypoplasia of parietal and chief cells are also characteristic features of Ménétrier disease.

A diagnosis of Ménétrier disease may be difficult to establish on analysis of mucosal biopsies alone because some of the histologic features mimic hyperplastic polyps.30 Clinical information is essential to establish a correct diagnosis. Ménétrier disease must be distinguished from other causes of enlarged gastric rugae, such as robust chronic gastritis, Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, and infiltration by tumor cells, such as lymphoma. Most of these other entities are easily distinguished histologically. For example, chronic gastritis shows abundant inflammation in the lamina propria without marked foveolar hyperplasia. The absence of foveolar hyperplasia and the presence of parietal cell hyperplasia in Zollinger-Ellison syndrome help to distinguish this lesion from Ménétrier disease. Lymphoma and other infiltrating tumors may mimic Ménétrier disease grossly, but biopsies are typically diagnostic.

Treatment

In the past, the treatment of Ménétrier disease was mainly supportive and provided in the form of serum albumin and nutritional supplementation. In severe cases, gastrectomy was and often still is necessary. However, studies have shown remarkable efficacy of treatment with a monoclonal antibody against the epidermal growth factor receptor, which is also a TGF-α receptor.79 These successes have been replicated in many patients.75,80–82 These outcomes validate the pivotal role of TGF-α in the pathogenesis of Ménétrier disease and demonstrate the potential of this mechanistic approach of targeted biologic therapy.

Inflammatory Polyps

Inflammatory Retention Polyp

Inflammatory retention polyps are uncommon lesions that usually occur in association with H. pylori gastritis. Some cases are associated with hypergastrinemia.16,17,83 Endoscopically, they are sessile lesions with a smooth surface contour. Microscopically, prominent foveolar cysts filled with retained mucus and various numbers of neutrophils are characteristic features (Fig. 20.8). The stroma is often edematous and may contain prominent polymorphonuclear and mononuclear inflammatory infiltrates. Deeper areas of the polyp are typically devoid of epithelium, characterized instead by an edematous inflammatory stroma and, in some cases, a loose proliferation of small blood vessels. Similar to other inflammatory polyps, retention polyps may regress after eradication of the underlying gastritis.

Polypoid Gastritis

Polypoid gastritis develops as a result of exuberant chronic gastritis. It is characterized by localized expansion of the lamina propria by inflammatory cells and lymphoid aggregates, which results in polyp formation. Polypoid gastritis typically occurs in patients 10 years younger than those with hyperplastic polyps, supporting the idea that this form is a precursor to the latter. The major risk factor is H. pylori gastritis.84 Less commonly, polypoid gastritis may develop as a result of chronic atrophic gastritis. Polypoid gastritis is identified in approximately 1% of all patients who undergo upper GI endoscopy.

Pathologically, the polyps are well-circumscribed nodules that usually measure less than 0.5 cm in diameter. They are most common in the antrum but can be located anywhere in the stomach. Histologically, they are characterized by epithelial regeneration with increased mitotic activity, marked acute and chronic lamina propria inflammation (Fig. 20.9), and nodular lymphoid aggregates. The polymorphic mixed inflammatory infiltrate, which includes neutrophils, plasma cells, and lymphocytes, and the absence of a homogeneous population of atypical lymphocytes and lymphoepithelial lesions are useful features for distinguishing these lesions from lymphoma.

Hamartomatous Polyps

The most common hamartomatous lesions of the stomach are fundic gland polyps, although classification of these lesions as hamartomas is controversial. Other less common hamartomatous polyps are usually associated with distinct polyposis syndromes, such as Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, juvenile polyposis, or rarely, Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. In most instances, an accurate diagnosis requires correlation of the pathologic findings with relevant clinical and endoscopic information.85

Fundic Gland Polyp

Clinical Features and Pathogenesis

Fundic gland polyps may be sporadic or familial. They were originally reported as a manifestation of FAP.86–88 These polyps are now recognized as one of the most common types of gastric polyps.1 The apparent increase in incidence may reflect the widespread and increasing use of proton pump inhibitors, which have been strongly implicated in sporadic fundic gland polyp pathogenesis.89–92 In one series, fundic gland polyps were more common than hyperplastic polyps and represented the most common type of gastric polyp (77% of all gastric polyps).1

Detection of fundic gland polyps in children should always prompt consideration of FAP. In addition, up to half of fundic gland polyps are associated with symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux.1 Fundic gland polyps occur more often in women, with an average age of 50 to 60 years at diagnosis.1,93 Fundic gland polyps may also develop in patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. As many as 90% of patients with FAP have fundic gland polyps within the oxyntic mucosa.86,87,94–98

The contrasting natural histories and biologic features of sporadic and FAP-associated fundic gland polyps are discussed later. In molecular terms, FAP-associated polyps usually have adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene mutations99 and less frequently demonstrate mutations in the gene for β-catenin (CTNNB1), another component of the APC signaling pathway (Table 20.4).99–101 Conversely, sporadic fundic gland polyps are associated with activating CTNNB1 mutations in more than 90% of cases but show APC gene mutations in less than 10% of cases.96,99,102 Tumor suppressor gene methylation occurs more commonly in sporadic than FAP-associated fundic gland polyps, but the presence or absence of tumor suppressor gene methylation is not specifically associated with the development of dysplasia in these lesions.88,102–107 Although it remains controversial whether H. pylori can induce fundic gland polyp regression, it is true that H. pylori infection is uncommon in patients with fundic gland polyps.87,108,109

Table 20.4

Comparison of Sporadic and Syndromic Fundic Gland Polyps

| Feature | Sporadic | Syndromic |

| Number | Usually solitary (40% multiple) | Typically multiple (90%) |

| Male-to-female ratio | F > M | M = F |

| Mean age | 52 | 40 |

| Mutations | CTNNB1 ≫ APC | APC > CTNNB1 |

| Dysplasia risk | Low (<1%) | High (as much as 48%) |

| Incidence | 0.8-1.4% | 50-90% |

APC, Gene for adenomatous polyposis coli; CTNNB1, gene for β-catenin; F, female; M, male.

Pathologic Features

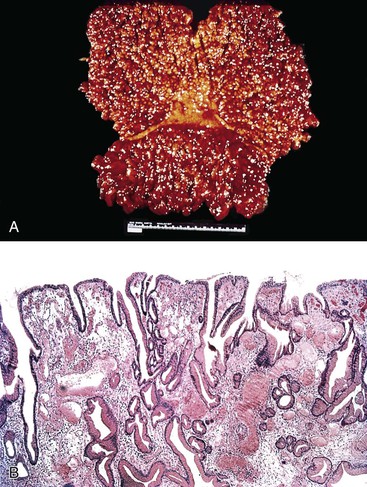

Fundic gland polyps are smooth, sessile, well-circumscribed lesions that occur exclusively in gastric oxyntic mucosa. They may be single or multiple, particularly in FAP patients. When multiple in patients with FAP, the term fundic gland polyposis may be used. One study of FAP-associated fundic gland polyps found an average of four polyps per patient, with a range of 1 to 11.93 Fundic gland polyps are most often smaller than 1.0 cm in diameter, but lesions as large as 2 to 3 cm have been reported.

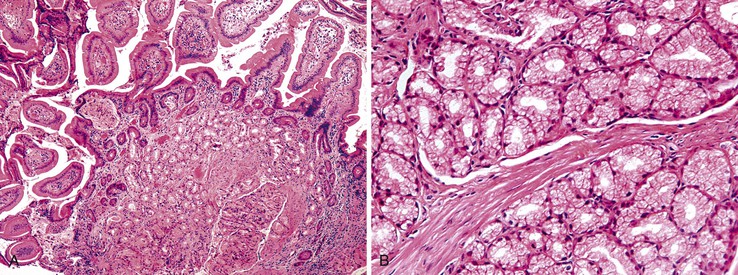

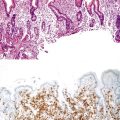

Histologically, fundic gland polyps are composed of cystically dilated and architecturally irregular fundic glands (Fig. 20.10). Fundic glands, which often assume a microcystic configuration or show prominent budding, are lined by flattened parietal and chief cells and occasional mucinous foveolar cells. Inflammation is typically absent or minimal. The surface and foveolar epithelium in fundic gland polyps are atrophic.

Natural History and Treatment

Sporadic fundic gland polyps are considered benign lesions with almost no malignant potential. Dysplasia occurs in less than 1% of these lesions.5,87,96,106,107,110–114 In contrast, dysplasia may be present in as many as 48% of FAP-associated fundic gland polyps.5,87,102,104–107,110–113,115,116 When present, dysplasia is usually low-grade. High-grade dysplasia has been reported only in a single sporadic fundic gland polyp, but the prevalence of high-grade dysplasia in FAP-associated lesions ranges from 0% to 12.5%.87,106,107,110,111,113 Similar to dysplasia in adenomas and hyperplastic polyps, analysis of dysplasia in fundic gland polyps usually reveals intestinal-type differentiation characterized by elongated hyperchromatic nuclei, an increased nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio, and nuclear pseudostratification that extends to the surface of the polyp (Fig. 20.11).

When hyperchromaticity and nuclear enlargement are limited to the proliferative zones of the polyp, particularly in the setting of active inflammation, regenerative atypia should be considered. The risk of malignant transformation is rare, and the few cases of adenocarcinoma have all been reported for FAP patients.

All dysplastic fundic gland polyps should be completely resected. Although formal surveillance guidelines have not been established, the data suggest that surveillance of FAP patients for dysplastic fundic gland polyps should be considered on an individual basis. Surveillance for duodenal adenomas, particularly periampullary lesions, and less common gastric adenomas may also be performed.

Peutz-Jeghers Polyp

Clinical Features and Pathogenesis

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome is an autosomal dominant syndrome characterized by the presence of mucocutaneous pigmentation and multiple GI hamartomatous polyps.117,118 The disease occurs equally in men and women. Patients usually are diagnosed in the second or third decade of life and have abdominal pain, GI bleeding, or less commonly, obstruction.

Hamartomatous polyps in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome may occur in any portion of the GI tract, but they are most common in the small intestine. Gastric lesions occur in 25% to 50% of patients. Because of their small size, gastric Peutz-Jeghers polyps are usually asymptomatic. Morphologically identical polyps can occur in McCune-Albright syndrome, which is caused by somatic activating mutations in the GNAS gene.119

Most cases of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome are caused by a germline mutation of the serine-threonine kinase STK11/LKB1 tumor suppressor gene.120–123 The function of this gene product is not entirely understood, but it is an important component of adenosine monophosphate (AMP) kinase/mTOR and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) signal transduction pathways.124–127 Tuberous sclerosis genes TSC1 and TSC2 are also downstream effectors of STK11/LKB1.126 Some of these signaling events may take place in mesenchymal rather than in epithelial, cells,128 which is consistent with reports of wnt5a signaling defects in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome.129–131

Dysplasia and carcinoma are rare in gastric polyps, with an estimated incidence of 2% to 3%. However, they may develop at a young age. For example, in one series of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome patients with gastric cancer, carcinoma developed at a mean patient age of 27 years.132

Lkb1-knockout mice develop GI hamartomatous polyposis similar to that in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome.133,134 These mice represent a unique opportunity to investigate new therapeutic agents, such as specific kinase inhibitors. For example, some studies of Lkb1 heterozygous mice and patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome suggests that cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition may ultimately prove beneficial in chemoprevention of polyposis.135,136

Pathologic Features

Peutz-Jeghers polyps may be sessile, but they are more commonly pedunculated and are usually less than 1 cm in the largest dimension. Rarely, larger lesions may develop. The gross appearance is similar to Peutz-Jeghers polyps in other portions of the GI tract, and they often have a velvety papillary or villiform surface. They occur most commonly in the antrum but may develop in any part of the stomach.

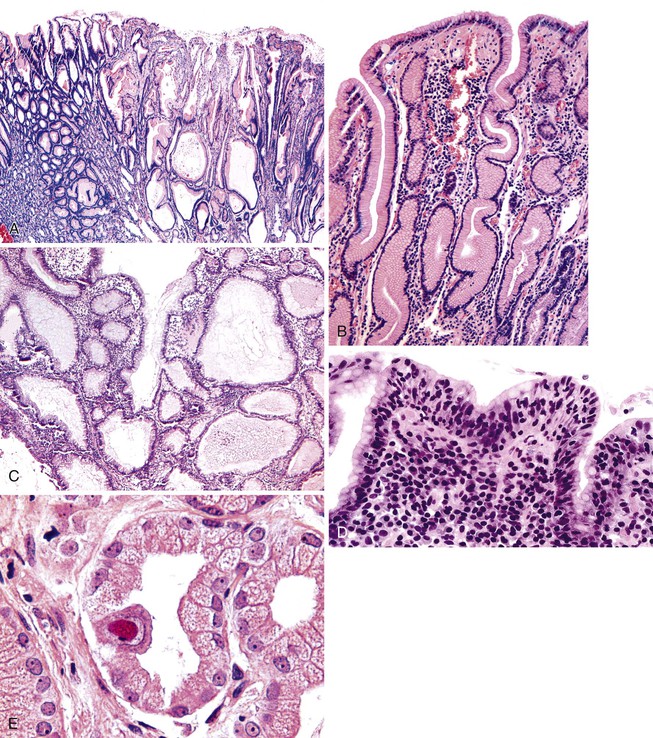

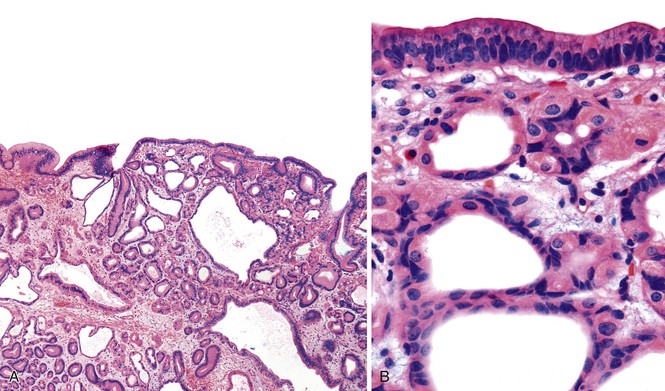

Microscopically, gastric Peutz-Jeghers polyps have a complex, arborizing architecture. Irregular bundles of smooth muscle extend from the muscularis mucosae into the lamina propria of the papillary projections and extend to the polyp surface (Fig. 20.12). Marked surface and foveolar hyperplasia with cystic change is often identified. Glandular atrophy is common, and a mild degree of lamina propria edema, congestion, and inflammation may also be apparent. The morphologic features are essentially similar to those of gastric hyperplastic polyps, with the exception that hamartomatous polyps often have a more fully developed and prominent smooth muscle component. However, gastric Peutz-Jeghers polyps are defective in glandular differentiation.137 For polyps occurring in oxyntic mucosa, this can be recognized by a paucity of parietal cells.137

Although gastric Peutz-Jeghers polyps are usually clinically silent, they can lead to intussusception. There are also rare examples of patients who have vomited large polyps, presumably as a result of autoamputation.138 Dysplasia can occur in Peutz-Jeghers polyps (Fig. 20.13), but this is uncommon in gastric lesions. There is no consensus on appropriate surveillance or follow-up of gastric Peutz-Jeghers polyps with or without dysplasia, although general guidelines have been proposed.139,140

Juvenile Polyp

Clinical Features and Pathogenesis

Sporadic gastric juvenile polyps are rare. They may occur as part of generalized juvenile polyposis coli or as part of the rare gastric subtype of this syndrome.141–143 Gastric juvenile polyps occur in 15% to 25% of patients with generalized juvenile polyposis coli. Between 20% and 50% of patients with gastric juvenile polyps have a positive family history for juvenile polyposis coli, an autosomal dominant condition characterized by a genetic dysregulation of the TGF-β pathway. The mutation most commonly identified involves the SMAD4/DPC4 gene, which encodes a cytoplasmic intermediate in TGF-β signaling.144–147 However, this mutation occurs in only a minority of cases.148–150 Possible gene candidates include PTEN, which is mutated in Cowden syndrome.151,152

Pathologic Features

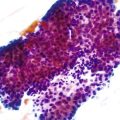

The gross and microscopic features of gastric juvenile polyps resemble those of gastric hyperplastic polyps (Fig. 20.14). In some instances, juvenile polyps may show a less pronounced degree of muscularis hyperplasia and a more prominently inflamed lamina propria than hyperplastic polyps. However, because of significant overlap, this feature particularly is not helpful. The essential features of juvenile polyps include surface and foveolar hyperplasia, cystic change, edema and inflammation of the lamina propria, smooth muscle hyperplasia, and some degree of intestinal metaplasia. The polyps may range from a few millimeters to several centimeters in diameter. Based on histology alone, it is not possible to reliably distinguish an isolated gastric juvenile polyp from a hyperplastic polyp, and knowledge of the clinical context, including the family history, is essential in establishing a correct diagnosis.142,153

Dysplasia and carcinoma occur with increased frequency among patients with generalized juvenile polyposis coli (see Fig. 20.14, E). Dysplasia in juvenile polyps appears histologically similar to that in hyperplastic polyps and is mostly of the intestinal type. It is characterized by mucin-depleted surface and foveolar epithelium; hyperchromatic, elongated nuclei with clumped chromatin; an increased nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio; a loss of polarity; and pseudostratification. Lack of surface maturation is typical of dysplasia. With increasing degrees of dysplasia, the nuclei become larger and show a greater degree of overlapping and loss of polarity, and the glands may take on a back-to-back or cribriform growth pattern.

Cronkhite-Canada Syndrome–Associated Polyps

Clinical Features

Cronkhite-Canada syndrome is a rare, nonhereditary generalized polyposis disorder. L. W. Cronkhite and W. J. Canada described the first two cases in 1955.154 The disease involves the stomach, small intestine, and colorectum but spares the esophagus.154–158 Unlike most syndromic polyposis disorders, Cronkhite-Canada syndrome typically appears in middle adulthood, with a mean age of onset at 59 years. Europeans and Asians are affected most often, and it occurs equally in men and women.

In addition to numerous GI polyps, patients with this disorder have alopecia, nail atrophy, skin hyperpigmentation, and vitiligo.159 Common GI complaints include diarrhea, weight loss, abdominal pain, anorexia, weakness, and hematochezia.154,155,160 The efficacy of corticosteroids for induction of remission and azathioprine for maintenance in some patients and positive immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4) staining of as many as 50% of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome polyps but not on other tissues have led some authorities to propose an autoimmune basis for this disorder.161 However, the cause of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome remains unknown.

Cronkhite-Canada syndrome is associated with a mortality rate of approximately 50%; most deaths are related to anemia and chronic wasting. Optimal therapy has not been established, but treatment options include nutritional support, antibiotics, corticosteroids, anabolic steroids, histamine receptor antagonists, and surgery, depending on the particular circumstances of the patient.161–168 Controlled therapeutic trials have not been reported. Up to 20% of patients with Cronkhite-Canada syndrome develop adenocarcinoma, which may occur in any portion of the GI tract, including the stomach.169–172 Although cancers may develop in polyps or nonpolypoid mucosa,173,174 the malignant potential of the polyps themselves remains largely unknown.

Pathologic Features

Advanced cases of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome show diffuse, irregular enlargement of the gastric rugae throughout the fundus and antrum. Numerous small to medium-sized polyps that typically measure between 0.5 and 1.5 cm in diameter may be superimposed on enlarged rugae (Fig. 20.15, A). The endoscopic appearance is similar to that of Ménétrier disease, except that the entire stomach is involved. Individual polyps may appear as elongated, papillary or villiform lesions or, alternatively, as clusters of sessile nodules, which can help in the diagnosis of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome.

Microscopically, changes in the stomach involve the interpolypoid and polypoid mucosa (see Fig. 20.15, B). As in Ménétrier disease, marked surface and foveolar hyperplasia with cystic change and atrophy of the glands are characteristic features. The lamina propria is often edematous and shows a mild to moderate degree of inflammation, but intestinal metaplasia is uncommon. The surrounding nonpolypoid mucosa shows alternating areas of atrophy and foveolar hyperplasia with microcystic changes. Unfortunately, a single biopsy from a Cronkhite-Canada syndrome–associated polyp may appear histologically identical to a juvenile polyp, hyperplastic polyp, or Ménétrier disease.30,156 However, knowledge of other clinical features of this disorder, particularly when combined with diffuse enlargement of gastric rugae and multiple polyps in all areas of the stomach, is helpful in establishing a correct diagnosis.

Embryonic Rests and Heterotopia

Pancreatic Heterotopia

Clinical Features

Ectopic rests of pancreatic tissue may develop in several parts of the upper GI tract when fragments of pancreas separate during embryonic rotation of the foregut. Foci of ectopic or heterotopic pancreatic tissue are most commonly found in the stomach,175–177 but they may also occur in the small intestine and colon.178 Between 0.1% and 4% of all gastric polyps have been reported to represent pancreatic heterotopia.179,180 Men and women are affected equally, and the average age at diagnosis is 45 years. However, pediatric patients also may be affected.181

Heterotopic pancreatic tissue is susceptible to many of the same inflammatory disorders that affect the native pancreas, including acute and chronic pancreatitis and cancer.181–183 Although pancreatic adenocarcinoma in ectopic pancreas is extremely uncommon, patients with adenocarcinoma of the pancreas and ectopic pancreas usually have pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia within the focus of the ectopic pancreas.184,185 Some cases may have elevated serum pancreatic enzyme levels.186

Pathologic Features

Pancreatic heterotopia most commonly occurs in the prepyloric and antral regions of the stomach, but it may rarely occur in the corpus.175,176 The lesions usually are less than 3 cm in diameter. Grossly, they consist of small submucosal nodules that protrude through the mucosa, often forming a central dimple or surface erosion, which represents a draining pancreatic duct. This finding offers an endoscopic clue to the diagnosis.187 Alternatively, pancreatic heterotopia can form a submucosal mass that can easily be mistaken for a well-differentiated neuroendocrine (carcinoid) tumor, well-differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma, or gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST).188–190 Ulceration and bleeding are common. Gastric heterotopic pancreas is frequently asymptomatic. Clinical symptoms are related to the location and size of the lesion and to the presence or absence of ulceration and bleeding.191,192

Microscopically, heterotopic pancreatic tissue may be composed of any one or combination of the three normal components of pancreatic parenchyma (i.e., ducts, acini, and islets). Exocrine (acinar tissue), endocrine (islet cells), and epithelial (ducts) elements in combination with pancreatic stroma may be found in various proportions. Some have proposed a classification in which type I pancreatic heterotopia includes acini, ducts, and islets; type II has only two of these elements, and type III has only one element.178 Histologically, each component of a heterotopic pancreas is similar to that which occurs in the normal pancreas (Fig. 20.16). Morphologically similar lesions develop in knockout mice that lack Hes1,193 a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor required for differentiation of secretory, endocrine, and Paneth cell lineages in the small intestine.

Acini within heterotopic pancreatic tissue typically drain into ducts lined by tall columnar epithelium. However, squamous metaplasia is occasionally identified. Thick, disorganized bundles of hyperplastic smooth muscle are often admixed with acini and ducts. When only smooth muscle and ducts are present, the lesion may be referred to as an adenomyoma.194 Endocrine elements, representing islets of Langerhans, are found in less than 50% of cases. Acute and chronic inflammation and necrosis, resembling acute and chronic pancreatitis of the native pancreas, may be seen. Gastric mucosa overlying the heterotopic pancreas often shows reactive changes, including foveolar hyperplasia, and has various degrees of edema, congestion, and inflammation.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of pancreatic heterotopia includes well-differentiated adenocarcinoma, gastritis cystica polyposa or profunda, and pancreatic acinar metaplasia. Pancreatic acinar metaplasia is far more common than pancreatic heterotopia and does not contain ducts, stroma, smooth muscle, or endocrine cells.175 Distinguishing well-differentiated adenocarcinoma, gastritis cystica polyposa or profunda, and heterotopic pancreatic tissue, particularly heterotopic foci associated with pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia, may be difficult if pancreatic acini and endocrine cells are not readily identifiable. However, most examples of pancreatic heterotopia lack architectural and cytologic atypia, atypical mitoses, and other features of malignancy that are common in well-differentiated carcinomas. In contrast to carcinoma, the ducts in pancreatic heterotopia normally grow in an organoid or lobular growth pattern. The duct profiles are smooth rather than irregular or jagged. The smooth muscle hyperplasia often associated with pancreatic heterotopia contrasts sharply with the desmoplasia often associated with invasive carcinoma.

Gastritis cystica polyposa or profunda may resemble pancreatic heterotopia, but the former is associated with mucosal hyperplastic changes, inflammation, and erosions. The submucosal epithelium of gastritis cystica polyposa or profunda is composed of mucinous columnar epithelium with or without gastric glands, which contrasts with the pancreatic duct–type epithelium that is characteristic of pancreatic heterotopia.

Pancreatic Acinar Metaplasia

Clinical Features

Pancreatic acinar metaplasia may occur in children or adults.195–198 It is identified in as many as 25% of gastric biopsies from adults.175,199 The mean age at which pancreatic acinar metaplasia is detected is 55 years, although patients of all ages may be affected.200,201 There is no gender preference.200,201

Pancreatic acinar metaplasia occurs most often in antral and cardiac (i.e., gastroesophageal junction) mucosa, typically on a background of little or no inflammation and often without glandular atrophy or intestinal metaplasia.175,196,198,201,202 However, pancreatic acinar metaplasia in the corpus should prompt consideration of autoimmune gastritis.202,203 Pancreatic acinar metaplasia has been associated with H. pylori infection,201 chronic gastritis,203 gastroesophageal reflux (when located near the gastroesophageal junction), and gastric adenocarcinoma.204 These associations do not necessarily hold true for pancreatic acinar metaplasia located above the gastroesophageal junction.201

Although the cause of pancreatic acinar metaplasia is unknown, it has been suggested that it represents a congenital rest, particularly for lesions that occur at the gastroesophageal junction.200 It may also be a type of metaplasia that develops in chronic gastritis.201–203

Pathologic Features

Pancreatic acinar–like cells are characterized by fine acidophilic granules in the apical cytoplasm and prominent basophilia of the basal portion of the cells. The cells are usually arranged in small nests or lobules, often in continuity with the surrounding gastric glands (Fig. 20.17).205 Alternatively, lobules of pancreatic acinar cells may be separated from the surrounding gastric mucosa by connective tissue and smooth muscle.205

When examined immunocytochemically or by electron microscopy, the cells are indistinguishable from pancreatic acinar cells. They contain exocrine secretory granules immunoreactive for exocrine pancreatic markers, such as lipase, trypsinogen, and pancreatic α-amylase.196,198,199 A few cells may be positive for neuroendocrine markers, such as chromogranin, somatostatin, gastrin, and serotonin, but this should not prompt confusion with endocrine cell dysplasia or a neuroendocrine (carcinoid) tumor. Some cells are positive for exocrine and neuroendocrine markers.196 However, immunohistochemistry is not required for diagnosis and is usually necessary only in a research setting.

Differential Diagnosis

The most common differential diagnosis is pancreatic heterotopia. The presence of ductal elements, pancreatic stroma, or well-defined islets effectively excludes pancreatic acinar metaplasia. Paneth cell metaplasia may also resemble pancreatic acinar metaplasia. However, well-developed zymogen granules in pancreatic acinar-like cells are small and easily differentiated from the larger, more refractile Paneth cell granules. Immunostains for trypsinogen and lipase may be helpful in diagnostically difficult cases.

Brunner Gland Nodules

In the duodenum, Brunner gland hyperplasia is usually related to chronic peptic duodenitis. It is unclear whether Brunner glands in the prepyloric region represent a hamartomatous process, represent proximal extension of hyperplastic duodenal Brunner glands into the distal stomach because of hyperchlorhydria, or are a consequence of chronic H. pylori gastritis.206–210

Histologically, Brunner gland nodules are composed of densely packed, cytologically benign Brunner glands that form a prominent submucosal nodule (Fig. 20.18). Pyloric obstruction may occur in rare and extreme cases.211,212