Polyps of the Large Intestine

Jason L. Hornick

Robert D. Odze

Introduction

Flexible sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy frequently reveal polypoid lesions that are either sampled or removed endoscopically. Broadly speaking, the term polyp refers to any localized projection above the surrounding colonic mucosa. The vast majority of colorectal polyps may be categorized as inflammatory, hamartomatous, or epithelial. In addition, polyps may develop from mesenchymal proliferations, benign or malignant hematolymphoid tissue, metastatic tumors, and a wide variety of non-neoplastic substances, such as air. The relative proportions of these various types of polyps depend on the type of population undergoing endoscopy (e.g., age, associated risk factors such as inflammatory bowel disease [IBD] or polyposis syndrome) and the method of investigation (e.g., sigmoidoscopy versus total colonoscopy), but hyperplastic and adenomatous polyps are by far the most common types. In one study of 1050 colonic polyps, 82% were adenomatous, 12% were hyperplastic, 3% were inflammatory, and only 1.5% were mesenchymal polyps such as lipomas and leiomyomas.1

Inflammatory Polyps

Inflammatory polyps are defined as intraluminal projections of mucosa that are formed of a non-neoplastic mixture of stromal and epithelial components and inflammatory cells. These include inflammatory “pseudopolyps,” which may or may not be related to IBD; prolapse-type inflammatory polyps and their many variants; and inflammatory myoglandular polyps.

Inflammatory Pseudopolyp

Inflammatory pseudopolyps represent areas of inflamed and regenerating mucosa that project above the level of the surrounding mucosa, which is frequently ulcerated. They generally develop as a response to either localized or diffuse inflammatory diseases (e.g., Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis), but they also occur in association with other disorders, such as ischemic colitis,2 neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis,3 and infectious colitis,4 and they commonly form at the edges of intestinal ulcers and mucosal anastomoses. The pathogenesis is related to full-thickness ulceration of the mucosa, followed by inflammation and regenerative hyperplasia of the intervening nonulcerated epithelium. In rare cases, the patient may have no apparent underlying inflammatory disorder.

Pathologic Features

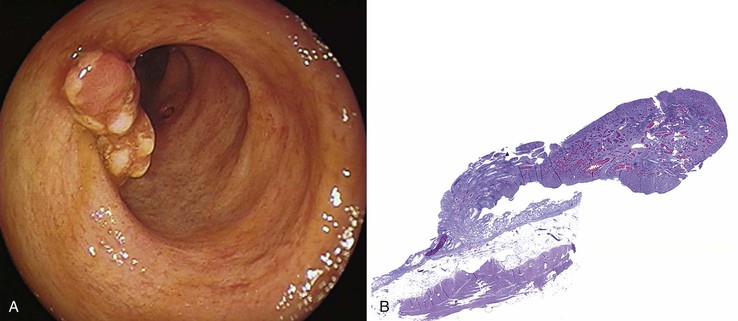

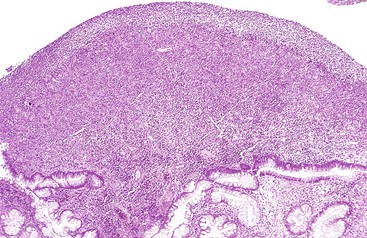

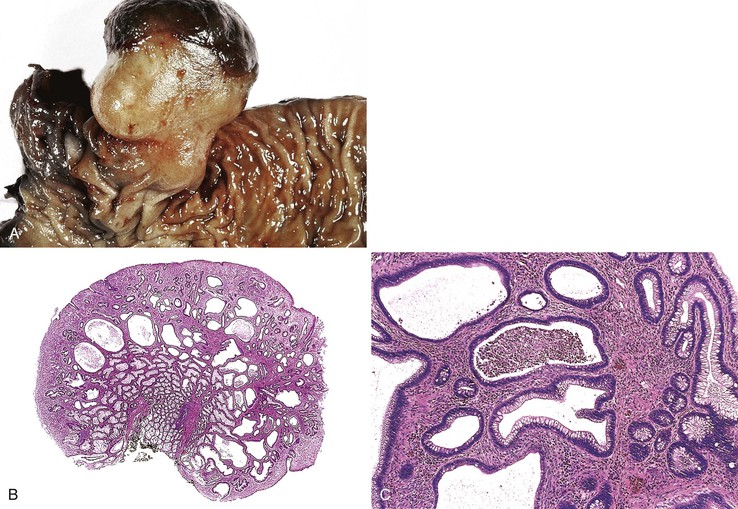

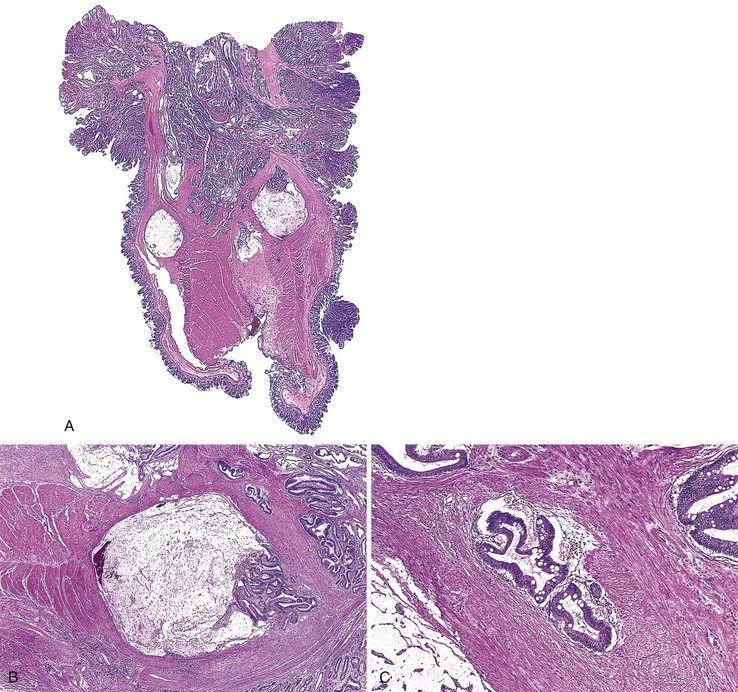

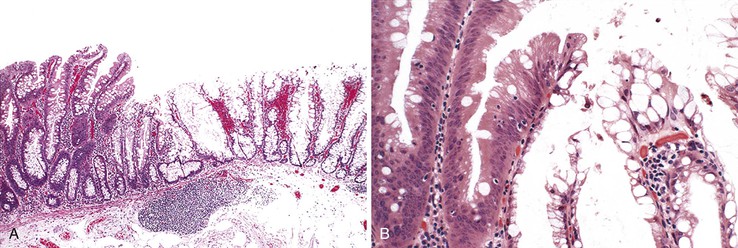

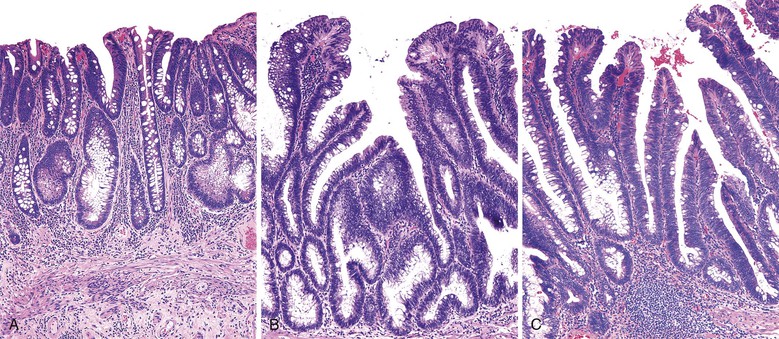

Grossly, inflammatory pseudopolyps may be sessile or pedunculated. They are almost always smaller than 2 cm, but so-called giant inflammatory polyps may grow to large sizes and cause obstruction.5,6 Filiform polyposis refers to the presence of numerous dense, filamentous polyps that can project several centimeters above the surrounding mucosa (Fig. 22.1).7 This form of polyposis is usually associated with IBD or, rarely, juvenile polyposis.

Histologically, some polyps, particularly those adjacent to ulcers or anastomotic sites, are formed entirely, or almost entirely, by inflamed granulation tissue. However, most inflammatory pseudopolyps are composed of a mixture of inflamed lamina propria and distorted colonic epithelium; surface erosions may or may not be present (Fig. 22.2). Colonic crypts are often dilated, branched, and hyperplastic, and neutrophilic cryptitis and crypt abscesses may be prominent. In the later stages of development, inflammatory polyps may consist of many finger-like projections of normal or near-normal mucosa surrounding a core of submucosal tissue.

Three potential pitfalls can occur in the histologic evaluation of inflammatory pseudopolyps. First, dysplasia may rarely develop in these lesions, particularly in those associated with IBD. Much more commonly, regenerating epithelium can be extreme, particularly in inflamed or eroded areas, simulating a neoplastic process. Careful attention to surface maturation, which is usually observed in regenerating epithelium and almost never in dysplasia, can help in making this distinction in difficult cases. Second, bizarrely shaped, enlarged, or multinucleated stromal cells that can mimic sarcoma (termed “pseudosarcoma”) may develop in inflammatory pseudopolyps.8 These cells may be spindled or epithelioid, and they often aggregate at the surface of the polyp, underneath areas of ulceration and granulation tissue (Fig. 22.3).

Finally, in many instances, the histologic appearance of inflammatory pseudopolyps may be indistinguishable from that of juvenile polyps. Distinction between these two types of lesions is based largely on clinical information, such as the age of the patient (almost all such polyps in young children are juvenile polyps), the presence or absence of a clinical history of a hamartomatous polyposis syndrome (juvenile polyposis, Cowden disease, and Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome [BRRS] can all have juvenile-type polyps),9 and the presence or absence of an underlying inflammatory disorder.

Natural History and Treatment

Inflammatory pseudopolyps tend to persist even after healing of the surrounding mucosa has taken place. They are frequently found in quiescent ulcerative colitis. These polyps have no increased tendency for neoplastic transformation. Treatment is usually directed at the underlying inflammatory condition. Rarely, surgical excision is indicated when large or numerous polyps cause symptoms due to bleeding or obstruction.5

Prolapse-Type Inflammatory Polyp

Mucosal prolapse syndrome was proposed by du Boulay and colleagues in 1983 as a unifying term for the clinicopathologic abnormalities underlying solitary rectal ulcer syndrome and related entities.10 However, prolapse-type inflammatory polyps more commonly develop as a result of localized protuberances of mucosa unrelated to the solitary rectal ulcer syndrome. The pathogenesis in all instances is related to traction, distortion, and twisting of mucosa caused by peristalsis-induced trauma; this leads to torsion of blood vessels and tissue damage, localized ischemia, and repair in the form of lamina propria fibrosis. Depending on the anatomic location of the injury and the underlying cause, these polyps may be referred to as inflammatory cloacogenic polyps of the anal transitional zone, inflammatory cap polyps, colitis cystica polyposa, or diverticular disease–associated polyps. All demonstrate some overlapping histologic abnormalities that are usually the result of mucosal prolapse.11 Inflammatory cap polyps, colitis cystica profunda, and diverticular disease–associated polyps are described in detail in later sections.

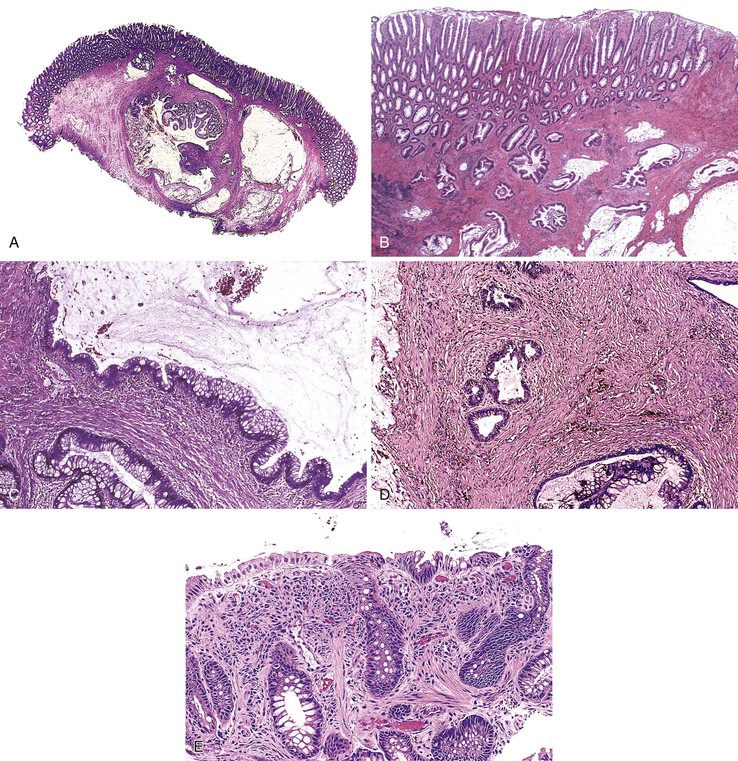

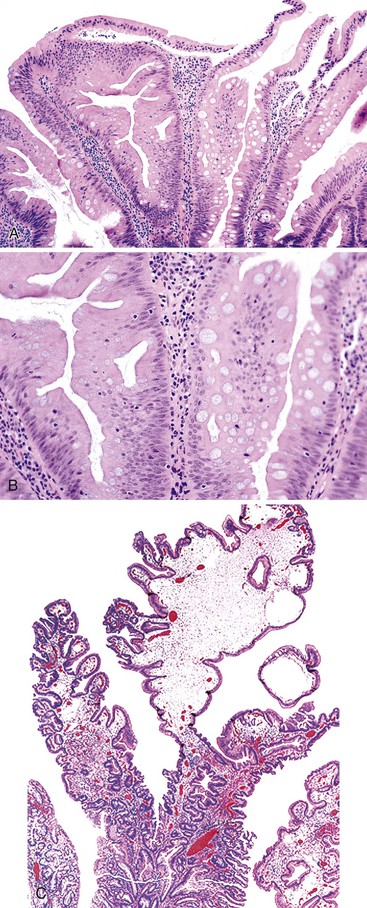

Additionally, solitary or multiple polyps that demonstrate common histopathologic features of mucosal prolapse have been variably called polypoid prolapsing mucosal folds11 or prolapse-induced inflammatory polyps.12 The classic histologic features of prolapse-induced inflammatory polyps include (1) a variable degree of fibromuscular hyperplasia of the lamina propria; (2) thickening, splaying, and vertical extension of the muscularis mucosae into the lamina propria; (3) crypt abnormalities (e.g., elongation, hyperplasia, architectural distortion, serration); and (4) a variable degree of inflammation, ulceration, and reactive epithelial change (Fig. 22.4).11,12

Inflammatory Cap Polyp (and Cap Polyposis)

Inflammatory cap polyps were first described in abstract form in 1985 by Williams and co-workers.13 These rare lesions usually occur in the setting of cap polyposis, in which dozens of these types of polyps develop. There is no sex predilection, and they occur over a wide age range.14 Clinically, patients with cap polyposis often are seen with diarrhea, mucoid stools, gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, and/or tenesmus. Occasionally, these symptoms are accompanied by severe hypoproteinemia. A direct loss of protein from cap polyps was confirmed in one 54-year-old woman by scintigraphy with the aid of technetium 99m–labeled diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA) complexed to human serum albumin.15

Endoscopically, most cap polyps are small, sessile or semipedunculated lesions that range in size from a few millimeters to 2 cm. The most common location is the rectum or rectosigmoid; less commonly, the descending colon is involved.16–19 Rarely, cap polyps may involve the entire colon and even the stomach.14,20 Multiple polyps are typically located at the crests of mucosal folds, separated by normal or edematous mucosa.

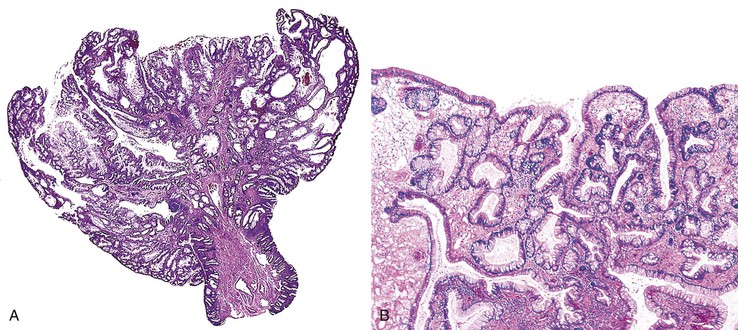

Histologically, cap polyps are non-neoplastic lesions composed of elongated, dilated, or tortuous hyperplastic colonic crypts with abundant inflammation in the lamina propria and a characteristic “cap” of inflamed and ulcerated granulation tissue (Fig. 22.5). Goblet cells of cap polyps have been shown by immunohistochemistry to express nonsulfated mucins.21 The intervening lamina propria typically contains increased acute and chronic inflammatory cells. The endoscopic “cap” is composed of an inflammatory exudate. Some polyps contain splayed smooth muscle fibers or fibrosis suggestive of a mucosal prolapse etiology.14,17

Many patients with multiple polyps require surgical resection for resolution of their symptoms,16,18,19 although some patients improve spontaneously14 or with therapy to eradicate Helicobacter pylori infection.20 Infliximab may also be effective therapy for cap polypsis.22 Isolated polyps are treated by simple polypectomy.

Colitis Cystica Profunda/Polyposa

Clinical Features

Colitis cystica profunda is a rare benign condition characterized by cystic dilatation and misplacement of mature crypts through the muscularis mucosae into the submucosa or deeper layers of the bowel wall. The term colitis cystica polyposa was first used by Virchow in 1863 to describe a case in which multiple polypoid lesions were produced by submucosal cysts.23 The term colitis cystica profunda subsequently came into use in 195724; most affected patients have both submucosal cysts and associated polypoid lesions. Similar lesions are found in the stomach (gastritis cystica profunda), where they are most frequently occur after Billroth II gastrectomy,25 and in the small bowel (enteritis cystica profunda), where they are often associated with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS).26

Rarely, colitis cystica profunda occurs as an isolated lesion (or lesions) in a patient with an otherwise apparently normal colon.27,28 However, most cases are associated with some form of colonic abnormality—most commonly, the solitary rectal ulcer syndrome,23,29,30 in which the lesions are located in the rectosigmoid. Distal lesions (sometimes called proctitis cystica profunda) have also been reported in paraplegics,31 in patients with self-inflicted rectal trauma,32 and in patients with postirradiation colonic strictures.33,34 Less commonly, a diffuse form of colitis cystica profunda occurs in patients with IBD (including ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease,35 and unclassified forms36) or infectious dysentery.23

The pathogenesis of colitis cystica profunda is believed to be related to prolapse and subsequent torsion and trauma of the mucosa and submucosa that leads to vascular compromise and ischemia.23 In solitary rectal ulcer syndrome (see Chapter 17), mucosal prolapse results in ischemia and ulceration by virtue of traction exerted on blood vessels.23 However, in colitis cystica profunda associated with infectious or idiopathic IBD, the pathologic changes probably occur as a result of misplacement and entrapment of regenerating glands in the submucosa during the process of reepithelialization and healing of ulcers.

Guest and Reznick23 reviewed the clinical features of 144 cases of colitis cystica profunda. Patients ranged in age from 4 to 76 years (median, 30 years). Males and females were approximately equally affected. The most common presenting symptoms were blood in the stool (68%), mucoid stools (43%), diarrhea (27%), tenesmus (13%), and abdominal discomfort (12%).23 Rarely, patients may be seen with obstruction.27

Pathologic Features

Grossly, colitis cystica profunda can be a focal, segmental, or diffuse lesion. Focal and segmental lesions can mimic invasive adenocarcinoma. Transrectal ultrasonography and other imaging modalities may aid in making the distinction by demonstrating multiple cysts limited to the submucosa and lack of lymph node involvement in the colitis cystica profunda lesion.37

Histologically, the condition is characterized by the presence of multiple cystically dilated, mucin-filled crypts in the submucosa and occasionally in the muscularis propria or serosa. The stroma surrounding misplaced crypts usually consists of lamina propria; this is helpful in distinguishing it from adenocarcinoma, which typically has a desmoplastic stroma. Furthermore, misplaced glands in colitis cystica profunda often grow in a lobular configuration without jagged borders or the unusual, irregularly shaped glandular profiles characteristic of adenocarcinoma. Misplaced crypts typically show either normal or reactive-appearing colonic epithelium. A mild degree of mucin depletion, pseudostratification, and increased mitotic activity may be observed as well. However, loss of nuclear polarity, an increased nucleus-to-cytoplasm (N : C) ratio, and atypical mitoses should alert one to the possibility of adenocarcinoma. Lamina propria surrounding misplaced glands and lack of dysplastic-appearing epithelium are key features that help distinguish colitis cystica profunda from invasive adenocarcinoma (Table 22.1; Fig. 22.6).

Table 22.1

Characteristic Features of Epithelial Misplacement (Colitis Cystica Profunda in Mucosal Prolapse and Enteritis Cystica Profunda in Peutz-Jeghers Polyps) Versus Invasive Adenocarcinoma

| Feature | Misplaced Epithelium | Invasive Adenocarcinoma |

| Architecture | Lobular arrangement of cystically dilated, mucin-filled crypts | Irregular crypts with back-to-back configuration, may be cystically dilated; variability in size and shape of crypts |

| Lamina propria around crypts | Present (may show fibrosis or fibromuscular obliteration) | Absent |

| Hemorrhage/hemosiderin | Usually present | Usually absent |

| Desmoplasia | Absent | Usually present |

| Dysplastic cytologic features | Absent | Present |

| Atypical mitoses | Absent | May be present |

In many patients with rectal prolapse, treatment of the defecation disorder itself (e.g., education to avoid straining at defecation, a high-fiber diet, bulk laxatives) leads to remission of colitis cystica profunda.29 Some patients require surgical resection because of obstruction,27 confusion with carcinoma, severe symptoms, or coexistent IBD.36

Diverticular Disease–Associated Polyp

Polyps that occur in association with diverticulosis are of two types: inverted diverticula and polypoid prolapsing mucosal folds. Polyps of the former type have been described in patients with inverted Meckel diverticula of the ileum (wherein they may cause intussusception),38 isolated inverted colonic diverticula, or inverted sigmoid diverticula in the setting of sigmoid diverticulosis.39,40 Inverted colonic diverticula usually range from 0.2 to 2 cm. They may be sessile or pedunculated but characteristically have the same color as the surrounding mucosa.40 These polyps tend to vanish with gentle pressure from the biopsy forceps or from air insufflation at endoscopy.40 Bowel perforation may occur as a result of endoscopic polypectomy in cases in which the inverted diverticulum mimics an adenoma.40

Polypoid prolapsing mucosal folds are the more common form of diverticular disease–associated polyps. Grossly, these appear as bright red, polypoid, or slightly elevated patches of mucosa in patients with sigmoid diverticulosis.41 Swollen mucosal folds seen between diverticular ostia may reveal an apical brown discoloration. More advanced lesions characteristically show small, brownish, polypoid protrusions of the mucosal folds. Polyps normally range from 0.5 to 3 cm.

Histologically, early lesions show vascular congestion, hemorrhage, and hemosiderin deposition. More advanced lesions reveal edema, capillary thrombi, lamina propria fibrosis, and crypt architectural changes such as dilatation and branching. The most advanced, “leaflike” polyps show changes typically seen in mucosal prolapse, such as smooth muscle ingrowth into the lamina propria, crypt hyperplasia, mucin depletion, and serrated hyperplastic changes of the epithelium. Epithelial hyperplasia may be marked and should not be mistaken for an adenoma.42 Rarely, one may see pseudosarcomatous changes of the stroma, characterized by enlarged and hyperchromatic myofibroblasts that should not be mistaken for sarcoma.42

Redundant mucosal folds occur in a large majority (90% to 100%) of patients with advanced sigmoid diverticulosis, although only a minority develop grossly polypoid lesions or frank prolapse-like histologic alterations of the mucosa (Fig. 22.7).43,44 Thickening of the taenia coli, which leads to shortening of the sigmoid, is believed to be the initiating pathogenetic event in the development of these lesions.

Patients with diverticular disease–associated polyps may develop chronic low-grade blood loss.45 Treatment is similar to that for diverticulosis in general and in many instances has been shown to result in regression of polyps.45

Inflammatory Myoglandular Polyp

Inflammatory myoglandular polyps were described by Nakamura and associates in 1992.46 They are rare, often underrecognized lesions. Among the 32 cases reported by Nakamura’s group, most polyps were solitary and located in the sigmoid colon (18 cases); the remainder were distributed among the transverse colon (8 cases), descending colon (3 cases), and rectum (3 cases). An inflammatory myoglandular polyp of the terminal ileum has also been reported.47 The most common symptom is occult or overt rectal bleeding.46 Affected patients are predominantly male, with a wide age range (15 to 78 years).46 The pathogenesis of these lesions is controversial. Chronic trauma and mucosal prolapse have been proposed as etiologic possibilities. However, some authors believe that these polyps represent a type of hamartoma.

Grossly, inflammatory myoglandular polyps range from 0.4 to 2.5 cm.46 Most are pedunculated and spherical and contain a smooth surface, either with or without surface erosion.48 The cut surface typically contains scattered mucin-filled cysts set within a dark brown stroma.46 Histologically, these polyps are composed of a treelike network of radially arranged smooth muscle, similar to Peutz-Jeghers polyps. Hyperplastic and cystically dilated crypts are typical (Fig. 22.8). At the periphery or surface of the polyp, one often finds luminal fibrinoinflammatory exudate and granulation tissue. The surface epithelium may appear regenerative, with a serrated or hyperplastic appearance, and may show mucin depletion. Frequently, hemosiderin deposition is noted within the lamina propria, reflecting areas of mucosal erosion and hemorrhage.46

The main features distinguishing juvenile polyps from inflammatory myoglandular polyps are the younger mean age of patients with juvenile polyps and the presence of only a trace amount of smooth muscle within the lamina propria of juvenile polyps. In contrast to inflammatory myoglandular polyps, Peutz-Jeghers polyps do not typically reveal surface erosions or a granulation tissue reaction. However, in some isolated cases, distinction between these entities may not be possible solely on histologic grounds.

Hamartomatous Polyps

Hamartomas are defined as overgrowths of cells and tissues native to the anatomic location in which they occur. In the GI tract, hamartomas typically incorporate both stromal and epithelial components. Hamartomas are most often solitary but may occur as part of a hamartomatous polyposis syndrome such as juvenile polyposis syndrome (JPS), PJS, Cowden syndrome, or the BRRS. Because of genotypic and phenotypic overlap between Cowden disease and BRRS, these two conditions likely represent variations of the same entity (known as PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome).49–52 Cronkhite-Canada syndrome, another form of GI polyposis, is believed to have an inflammatory rather than a genetic basis, but it is discussed in this section because of its histologic resemblance to JPS.

In aggregate, the hamartomatous polyposis syndromes account for less than 1% of the annual incidence of colorectal carcinoma in the United States and Canada.52 Isolated sporadic juvenile polyps and (less commonly) Peutz-Jeghers polyps also occur, but these have essentially no malignant potential.

Juvenile Polyps and Juvenile Polyposis

Clinical Features

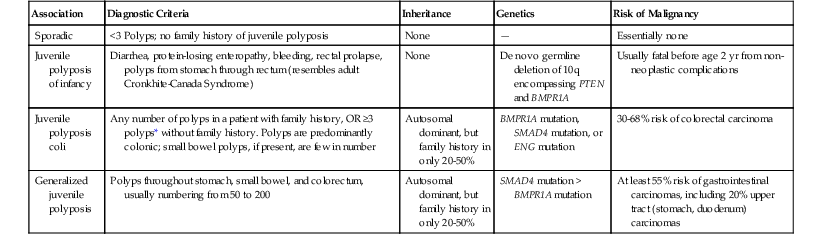

Juvenile polyps occur in four distinct settings: sporadic or isolated juvenile polyps of the colon, infantile JPS, juvenile polyposis coli, and generalized JPS (involving the stomach, small bowel, and colon) (Table 22.2).53 Sporadic or isolated juvenile polyps are the most common type of colon polyp among patients in the first decade of life, occurring in 2% of the pediatric population,9 but they are not uncommonly detected in adults as well. One study reported a mean age at occurrence of 5.9 years.54 Children usually are seen with either painless rectal bleeding or prolapse of the polyp through the rectum.54 Adults, if they are symptomatic at all, often are seen with rectal bleeding.

Table 22.2

Juvenile Polyps and Polyposis

| Association | Diagnostic Criteria | Inheritance | Genetics | Risk of Malignancy |

| Sporadic | <3 Polyps; no family history of juvenile polyposis | None | — | Essentially none |

| Juvenile polyposis of infancy | Diarrhea, protein-losing enteropathy, bleeding, rectal prolapse, polyps from stomach through rectum (resembles adult Cronkhite-Canada Syndrome) | None | De novo germline deletion of 10q encompassing PTEN and BMPR1A | Usually fatal before age 2 yr from non-neoplastic complications |

| Juvenile polyposis coli | Any number of polyps in a patient with family history, OR ≥3 polyps* without family history. Polyps are predominantly colonic; small bowel polyps, if present, are few in number | Autosomal dominant, but family history in only 20-50% | BMPR1A mutation, SMAD4 mutation, or ENG mutation | 30-68% risk of colorectal carcinoma |

| Generalized juvenile polyposis | Polyps throughout stomach, small bowel, and colorectum, usually numbering from 50 to 200 | Autosomal dominant, but family history in only 20-50% | SMAD4 mutation > BMPR1A mutation | At least 55% risk of gastrointestinal carcinomas, including 20% upper tract (stomach, duodenum) carcinomas |

* Some investigators use ≥3 polyps, ≥5 polyps, or ≥10 polyps.

First described in 1964 by McColl and co-workers,55 JPS is the most common GI hamartomatous polyposis syndrome. Separation of isolated juvenile polyps in childhood from JPS is important because of their divergent clinical behaviors and neoplastic risks (discussed later).53 Criteria for JPS are controversial and are rapidly evolving with the advent of newer molecular diagnostic techniques. At this point, the diagnosis should be suggested in any patient who has (1) any number of polyps in probands with a family history of JPS, (2) polyposis involving the entire GI tract, or (3) three or more colonic juvenile polyps. (This last figure has ranged from 3 to 10 polyps according to various diagnostic algorithms.53,56) Hamartomas do not occur outside the GI tract, but congenital birth defects are reported in 15% of JPS patients; these include malrotation of the gut and cardiac and genitourinary defects.53

In 1998, linkage analysis in a large Iowa kindred demonstrated that a gene for familial JPS maps to chromosome 18q21.1, a region containing both the DCC and the SMAD4 (DPC4, MADH4) tumor suppressor genes.57 Germline truncating mutations in SMAD4 were shown to be responsible for a subset of JPS patients.58 In 2001, germline mutations in the gene encoding bone morphogenic protein receptor 1A, BMPR1A, were also reported in JPS families lacking SMAD4 mutations.59 SMAD4 mutations account for 15% to 20% of patients with JPS, and BMPR1A mutations are found in 20% to 25% of JPS patients,53,60,61 suggesting that there is additional (as yet undefined) genetic heterogeneity in JPS. ENG mutations have now been reported in a small number of patients with JPS.62 Patients harboring SMAD4 mutations have a higher risk of generalized JPS,53 including massive gastric polyposis.63 Although JPS is transmitted in an autosomal dominant fashion, 25% of newly diagnosed patients have no family history and likely represent de novo mutations.49

JPS of infancy is a rare disorder with a poor prognosis that typically manifests in the first 2 years of life as generalized polyposis complicated by GI bleeding, diarrhea, rectal prolapse, and/or protein-losing enteropathy.53 Unlike conventional JPS, no family history is found in JPS of infancy. In 2006, Delnatte and colleagues reported that four patients with JPS of infancy were heterozygous for a de novo germline deletion of chromosome 10q, including the PTEN and BMPR1A genes, providing the first evidence of a genetic basis for this disorder.64

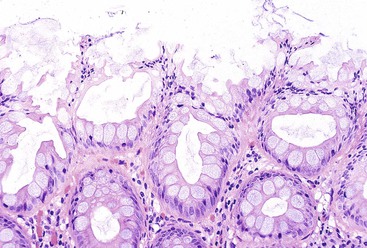

Pathologic Features

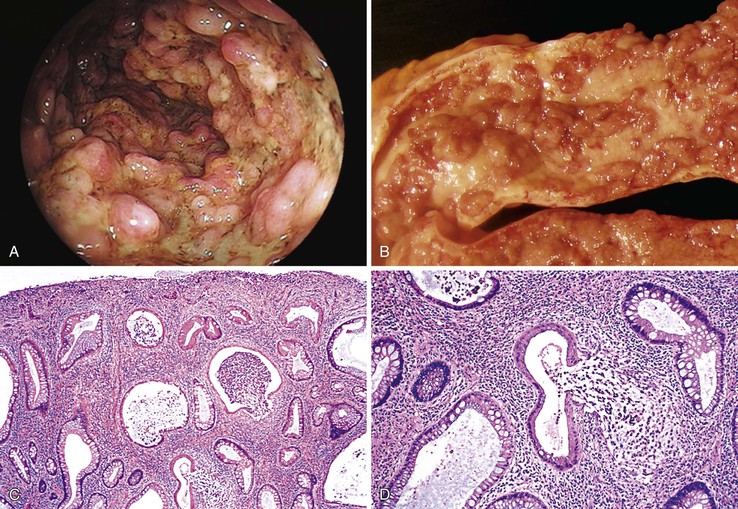

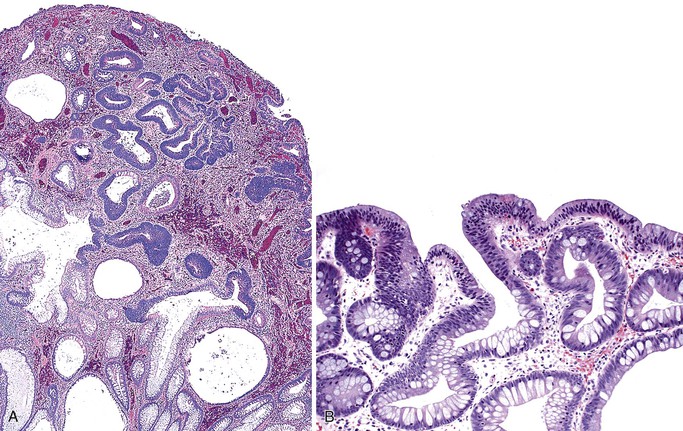

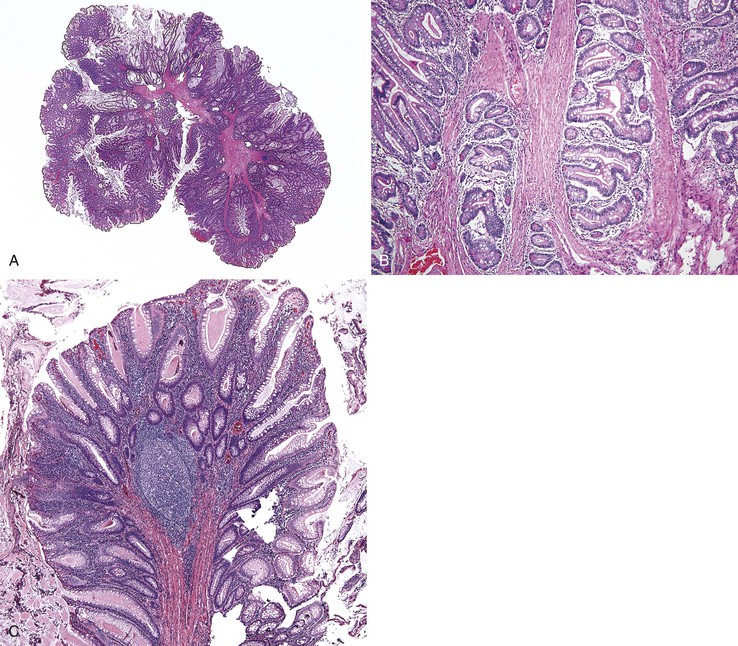

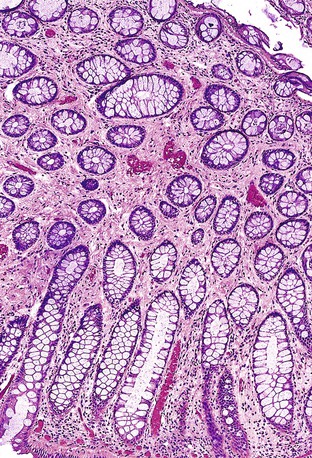

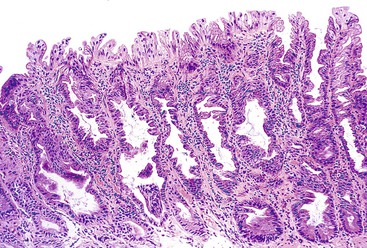

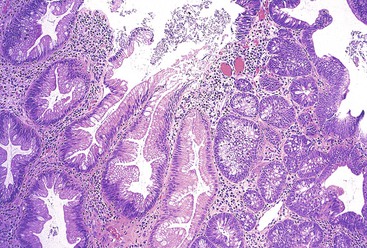

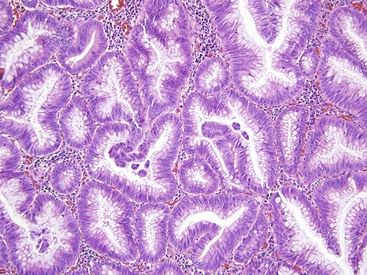

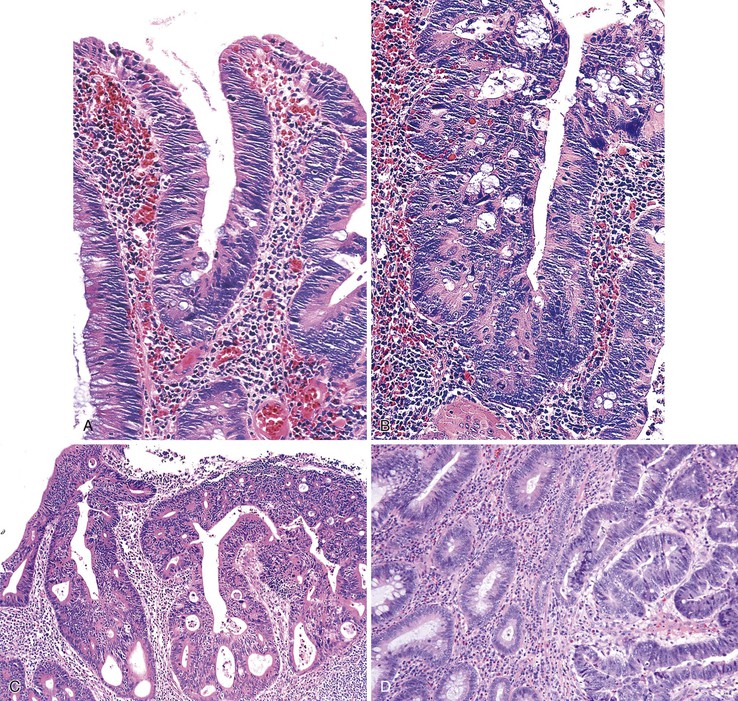

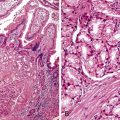

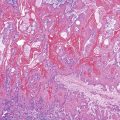

Isolated juvenile polyps are most common in the rectosigmoid colon (54%). However, 37% of patients have polyps proximal to the splenic flexure.54 In juvenile polyposis coli (polyps limited to the colon), polyps are most common in the rectosigmoid region and typically number as high as 200 (Fig. 22.9). The classic form of juvenile polyp (Fig. 22.10), found most frequently in isolated cases, is unilobulated and has a smooth, round surface contour. Histologically, these polyps are characterized by numerous cystic and dilated, often tortuous, crypts, some filled with neutrophils and inspissated mucin (which reflects the older term, mucous retention polyp). The intervening lamina propria is edematous and expanded by lymphocytes and plasma cells and occasional neutrophils and eosinophils. A few strands of muscle fibers may be present as well. In ulcerated cases, the epithelium may be markedly regenerative in appearance, simulating dysplasia. In patients with JPS, both classic (typical) and nonclassic (atypical) polyps are usually found. Nonclassic polyps (Fig. 22.11) are often larger, multilobulated, and villiform, frequently giving the gross appearance of several polyps attached to a single stalk. Histologically, compared with typical cases, they contain less abundant lamina propria and greater epithelial overgrowth, with many elongated, tortuous, and irregularly shaped crypts.65 The clonal origin of both the epithelium and the fibroblasts in juvenile polyps from SMAD4 mutation carriers has been shown by fluorescence in situ hybridization.66

Patients with JPS may have a combination of other types of polyps as well. Ganglioneuromatous proliferation of mature ganglion cells and nerve bundles may occur in the mucosa and the submucosa of polyps.67 Many patients also have separate adenomas or polyps with combined features of a juvenile polyp and an adenoma/dysplasia.68,69 In fact, true dysplasia (Fig. 22.12) has been detected in as much as 30% of polyps of JPS patients,65,70 but it is almost never observed in patients with isolated juvenile polyps. Gupta and associates reported dysplasia in only 1 of 331 juvenile polyps from 184 nonpolyposis patients.54

Natural History and Treatment

Patients with sporadic juvenile polyps have no increased risk for malignancy.71,72 Furthermore, they are not predisposed to the development of new juvenile polyps, and they do not require any particular type of follow-up.71 In contrast, estimates of the risk of GI carcinoma in JPS have varied widely. In one large kindred, the risk of upper and/or lower GI cancer in affected patients was 55%.73 In 1995, Desai and colleagues, in a reevaluation of data from the St. Mark’s Polyposis Registry, projected that the incidence of colorectal carcinoma through age 60 years was 68% (see Table 22.2).74 Surveillance recommendations should take into account the risks of both lower and upper tract cancer, including gastric cancer. Upper and lower endoscopy (including visualization of the entire colon) is usually recommended by age 15 years and should be repeated annually. Endoscopic polypectomies and histologic examination of all removed polyps should be performed until the patient is free of polyps, at which point the surveillance interval may be lengthened to 3 years. Consideration should be given to prophylactic gastrectomy or colectomy if diffuse polyposis cannot be controlled by endoscopic polypectomy or if there is a family history of GI carcinoma or dysplasia.75

Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome

Clinical Features

PJS is an autosomal dominant syndrome that is characterized by mucocutaneous pigmentation; distinctive hamartomatous polyps of the small intestine, colon, and stomach; and an increased risk for both intestinal and extraintestinal malignancies (see Chapters 20 and 21 for details). Estimates of the incidence of PJS vary widely, from 1 in 50,000 to 1 in 200,000 births.76,77 Significant phenotypic variability can occur within PJS kindreds, and patients may not have a family history of PJS. Most patients seek treatment during the second or third decade of life. In one study, the average age at presentation was 18 years, with a range from 2 to 62 years.78 Peutz-Jeghers polyps have also been described in neonates.79 The main clinical manifestations of PJS include mucocutaneous pigmentation (most characteristically on the vermilion border of the lips), GI polyposis, and an increased risk for GI carcinomas, as well as for extraintestinal benign and malignant tumors.

In 1997, the PJS locus was mapped to chromosome 19p13.3; this was achieved through the use of comparative genomic hybridization of PJS polyps in one patient, followed by targeted linkage analysis in 12 affected families.80 In 1998, two separate reports identified the STK11 (formerly LKB1) gene on 19p13.3 as the main causative gene in PJS.81,82 Germline mutations in the STK11 tumor suppressor gene, which encodes a novel serine threonine kinase, disrupt the function of the protein’s kinase domain.82 Overall, however, STK11 mutations have been found in only approximately 60% of familial and 50% of sporadic cases, suggesting the possibility of genetic heterogeneity in PJS.83

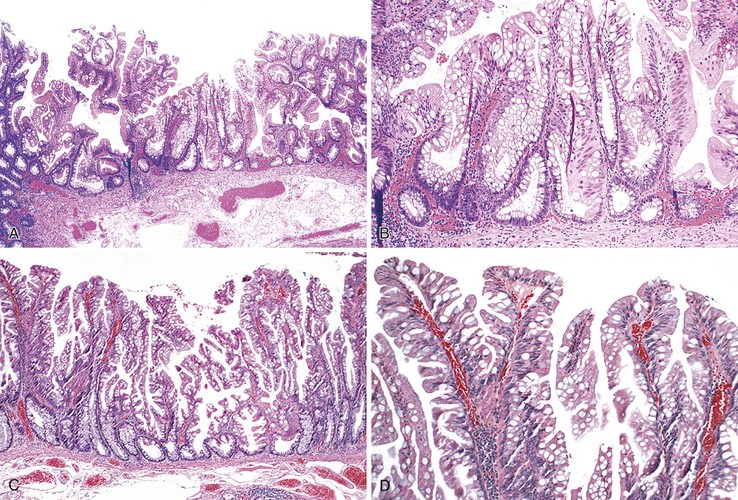

Pathologic Features

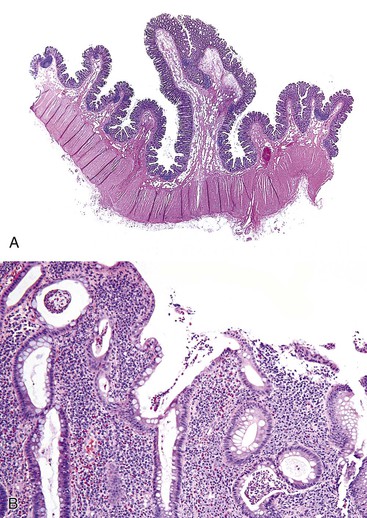

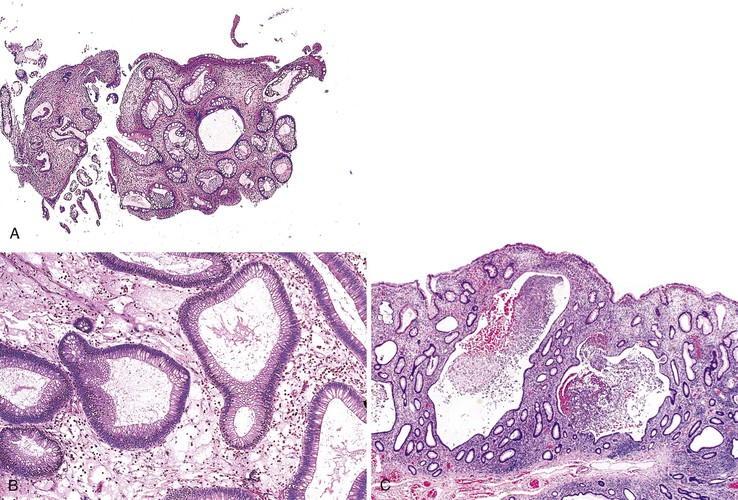

Hamartomatous polyps of PJS may occur throughout the GI tract but are most common in the small bowel (65% to 95%), followed by the colon (60%) and stomach (20% to 50%).84 Involved segments of bowel may harbor from 1 to 20 polyps, and these may vary in size from 0.5 to 3 cm. Well-developed polyps located in the small intestine and colon tend to be pedunculated.

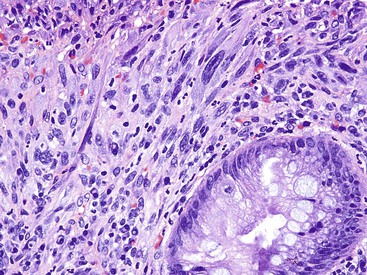

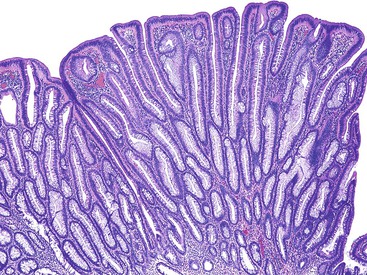

Microscopically (Fig. 22.13), the most prominent component is a distinctive, arborizing pattern of smooth muscle derived from the underlying muscularis mucosae. The lamina propria is usually normal in composition and cellularity and does not typically demonstrate increased inflammation. The overlying epithelium is composed of the normal epithelial cells typical of the involved segment of the GI tract. In most colonic Peutz-Jeghers polyps, the epithelium shows epithelial overgrowth and areas of hyperplasia, but dysplasia is unusual. Nevertheless, nondysplastic epithelium has been shown to be clonal.81

Studies of histologic and molecular alterations have shown that a subset of polyps progress through a sequence of hamartoma, adenoma (dysplasia), and then carcinoma. Somatic loss of the 19p13.3 allele occurs in a substantial portion of nondysplastic polyps; this (in conjunction with germline mutation at this locus) accounts for hamartoma formation.85,86 Dysplasia and carcinoma arise in hamartomas through the acquisition of additional genetic alterations at loci such as TP53 and β-catenin.86 Hizawa and co-workers documented “adenomatous” (dysplastic) foci in 9 (12.7%) of 71 Peutz-Jeghers hamartomas in the GI tract.87 In a study of 52 colonic Peutz-Jeghers polyps, Narita and associates found dysplasia in 3 (5.8%).88 Intramucosal and invasive carcinomas have been documented in Peutz-Jeghers polyps of the stomach, small bowel, and colon. Carcinomas are more likely to arise in patients with familial PJS. Only a single case report has described the occurrence of carcinoma in a nonsyndromic setting.89

Some Peutz-Jeghers polyps show foci of epithelial misplacement, pseudoinvasion, or herniation of benign epithelium into the intestinal wall (all synonymous for the phenomenon of enteritis cystica profunda) (Fig. 22.14). Shepherd and colleagues studied 491 Peutz-Jeghers polyps and reported epithelial misplacement in 10% of small intestinal polyps; however, this phenomenon was not observed in gastric or colonic polyps (see Chapters 20 and 21).90 Polyps with epithelial misplacement are characterized by intramural mucinous cysts that can involve all layers of the bowel wall, including the serosa. Grossly and histologically, these polyps can simulate invasive adenocarcinoma.91 Helpful histologic discriminators between pseudoinvasion and true carcinoma include the following: (1) lack of cytologic atypia in the deep glands, with a normal composition of epithelial cell types; (2) hemosiderin deposition; and (3) the presence of deep mucinous cysts in pseudoinvasion. Another potential pitfall is the overdiagnosis of misplaced dysplastic epithelium as invasion.92 Helpful discriminating features in these cases include the presence of both nondysplastic and dysplastic epithelium within the dilated misplaced crypts, the presence of lamina propria around the displaced crypts, and the lack of a desmoplastic response in noninvasive cases.

Natural History and Treatment

Non-neoplastic GI complications of PJS include GI bleeding and abdominal pain related to intussusception or luminal obstruction by large polyps. Intussusception is frequent (occurring in 47% of 222 Japanese PJS patients in a series by Utsunomiya and co-workers93) and is most common in the small intestine, caused in part by the pedunculated nature of the small bowel and colonic polyps. Prolapse of pedunculated PJS polyps through the rectum may also occur.93

Neoplastic complications of PJS include an increased frequency of both GI and extraintestinal neoplasms. Numerous early case reports attest to the increased risk of gastric, small intestinal, and colonic malignancy in PJS, although the absolute risk was debated and was initially thought to be relatively low. Subsequent studies suggested a high risk for cancer development. In a retrospective study from the Mayo Clinic spanning 50 years, noncutaneous cancers developed in 18 (53%) of 34 PJS patients, with a mean age of 39.4 years at the time of cancer diagnosis.94 In particular, the relative risk of GI carcinoma (predominantly colon cancer) in this study was 50.5, and in women with PJS, the relative risk of breast and gynecologic cancers was 20.3. In a meta-analysis of cancer risk in PJS, Giardiello and associates calculated a cumulative risk for malignancy of 93% in patients 15 to 64 years of age.95 In that study, the cumulative risks were as follows: breast cancer, 54%; colon cancer, 39%; pancreatic cancer, 36%; gastric cancer, 29%; ovarian cancer, 21%; and small intestinal cancer, 13% (Table 22.3). Furthermore, significantly increased relative risks were found for cancers of the following organs: esophagus (57), stomach (213), small intestine (520), colon (84), pancreas (132), lung (17), breast (15.2), uterus (16), and ovary (27). Although a statistically significant increased risk for either testicular cancer or cervical cancer could not be demonstrated in Giardiello’s study, distinctive tumors in these sites have been reported in PJS. A study by Lim and colleagues of 240 PJS patients harboring germline mutations in LKB1 also reported high cancer risks for these patients.96 By the age of 60 years, the risk for pancreatic carcinoma in PJS patients was 8%, the risk for breast cancer was 32%, and the risk for colorectal cancer was 30%.

Table 22.3

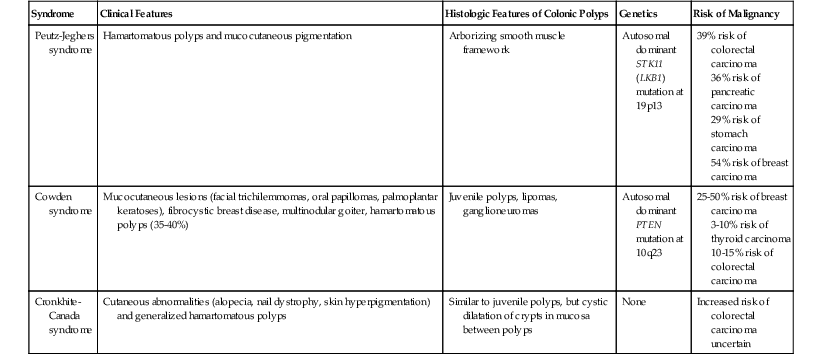

Other Hamartomatous Polyposis Syndromes

| Syndrome | Clinical Features | Histologic Features of Colonic Polyps | Genetics | Risk of Malignancy |

| Peutz-Jeghers syndrome | Hamartomatous polyps and mucocutaneous pigmentation | Arborizing smooth muscle framework | Autosomal dominant STK11 (LKB1) mutation at 19p13 |

39% risk of colorectal carcinoma 36% risk of pancreatic carcinoma 29% risk of stomach carcinoma 54% risk of breast carcinoma |

| Cowden syndrome | Mucocutaneous lesions (facial trichilemmomas, oral papillomas, palmoplantar keratoses), fibrocystic breast disease, multinodular goiter, hamartomatous polyps (35-40%) | Juvenile polyps, lipomas, ganglioneuromas | Autosomal dominant PTEN mutation at 10q23 |

25-50% risk of breast carcinoma 3-10% risk of thyroid carcinoma 10-15% risk of colorectal carcinoma |

| Cronkhite-Canada syndrome | Cutaneous abnormalities (alopecia, nail dystrophy, skin hyperpigmentation) and generalized hamartomatous polyps | Similar to juvenile polyps, but cystic dilatation of crypts in mucosa between polyps | None | Increased risk of colorectal carcinoma uncertain |

Surveillance in PJS is indicated for removal of GI polyps and for the early detection of both GI and extraintestinal neoplasms.76,97 Surveillance recommendations for the GI tract include (1) colonoscopy every 2 to 3 years beginning at age 18 years and (2) upper endoscopy with either push enteroscopy or double-contrast radiology for imaging of the entire small bowel every 2 to 3 years beginning at age 18 years. In women, monthly breast self-examinations should begin at age 18 years, and semiannual clinical breast examinations and annual mammography should begin at age 25 years. Minimum gynecologic surveillance recommendations include annual pelvic examinations and Papanicolaou smears in women and annual testicular examinations in men. Because of the clearly documented increased risk for pancreatic carcinoma, some authors also advocate pancreatic ultrasound examinations every 1 to 2 years.52,76

Cowden Syndrome

Clinical Features

Cowden syndrome is an autosomal dominant hamartoma/neoplasia syndrome that bears the family name of the original patient described by Lloyd and Dennis in 1963.52 In 1996, the susceptibility locus for Cowden syndrome was mapped to chromosome 10q22-23,98 and in 1997, germline mutations in the PTEN gene (phosphatase and tensin homolog, deleted on chromosome 10) on 10q23 were first reported in families with this syndrome.99,100 Since that time, mutations of the PTEN tumor suppressor gene or its promoter have been identified in 80% to 85% of patients who meet the strict operational diagnostic criteria set forth by the International Cowden Consortium.51,101

Hamartomas in Cowden syndrome affect all three germ cell layers but most commonly arise from ectodermal and endodermal elements. Almost all patients (90% to 100%) have mucocutaneous lesions that include trichilemmomas, acral keratoses, and oral papillomas.51 Breast lesions affect the majority of female patients and include fibroadenomas, fibrocystic disease, and adenocarcinomas (25% to 50%).51 Breast carcinoma is occasionally reported in men as well.102 Thyroid abnormalities, such as multinodular goiter and follicular adenoma, are found in one half to two thirds of patients. Thyroid carcinoma occurs in 3% to 10% of patients.51 Macrocephaly, cerebellar gangliocytoma, and genitourinary malformations are also frequent components of Cowden syndrome. Increased risks for endometrial carcinoma and renal cell carcinoma have been added to the operational criteria for Cowden syndrome.101,103

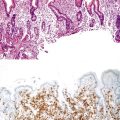

Pathologic Features

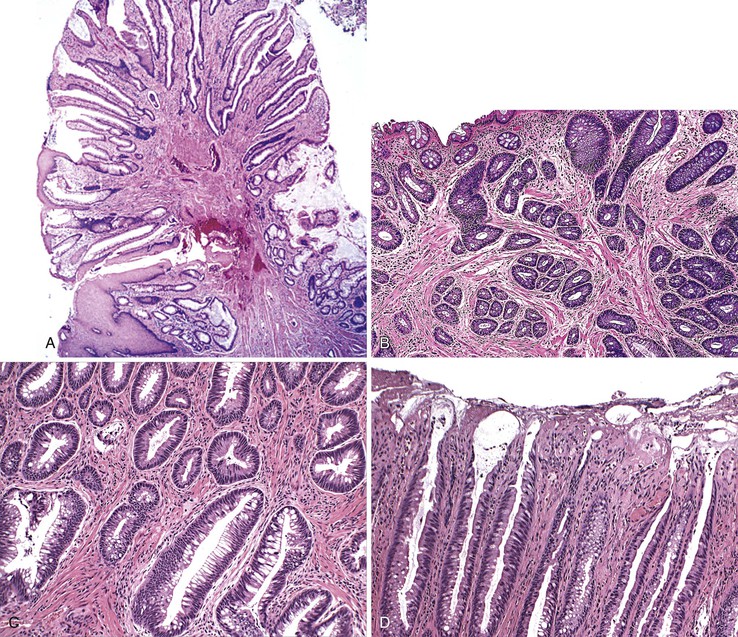

GI hamartomas are found in only 35% to 40% of patients with Cowden syndrome. Hamartomatous polyps may affect the stomach, small bowel, and colon (Fig. 22.15). The most common esophageal manifestation is glycogenic acanthosis. Most polyps resemble juvenile polyps and consist of cystically dilated, mucin-filled crypts set within an abundant lamina propria.104,105 Colonic lipomas, fibrolipomas, fibromas,106 ganglioneuromas, and adenomas107 have also been reported in Cowden syndrome. Among these polyps, polypoid ganglioneuromas are most specific for Cowden syndrome.108 Loss of expression of the wild-type PTEN allele, coupled with the germline PTEN mutation, was demonstrated in both GI hamartomas and colonic adenomas of several patients with Cowden syndrome.107

Natural History and Treatment

Recent studies have demonstrated that the lifetime risk of colorectal adenocarcinoma in patients with Cowden syndrome with PTEN mutations is 10% to 15%.109,110 For this reason, endoscopic surveillance of the GI tract has been recommended. Perhaps more importantly, screening and surveillance are directed at breast and thyroid malignancies.52 Recommendations for women include monthly breast self-examinations, annual clinical breast examinations beginning in late adolescence, and mammography beginning at age 25 years. Annual clinical examination of the thyroid in both sexes should begin in late adolescence with or without parallel use of thyroid ultrasonography every 1 to 2 years.52

Cronkhite-Canada Syndrome

Clinical Features

Cronkhite-Canada syndrome is a nonhereditary polyposis syndrome of unknown etiology (see also Chapter 17). Since the first description of this syndrome by Cronkhite and Canada in 1955,111 hundreds of cases have been reported. Although it is worldwide in distribution, most cases originate from Japan, Europe, or the United States. Unlike most polyposis syndromes, most patients are seen in middle adulthood (mean age, 59 years).112 Infantile cases of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome are only rarely reported.113

Colonic polyps associated with the Cronkhite-Canada syndrome occur in association with distinct ectodermal abnormalities, such as alopecia of both the scalp and body hair, dystrophy of the nails, and skin hyperpigmentation.111 Skin lesions are usually manifested by the presence of light to dark brown macules on the extremities, face, neck, palms, and soles.112 Affected patients often are seen with a variable combination of diarrhea, weight loss, nausea and vomiting, anorexia, and GI bleeding. In some cases, diarrhea may result in severe electrolyte abnormalities, with the development of seizures or tetany.112

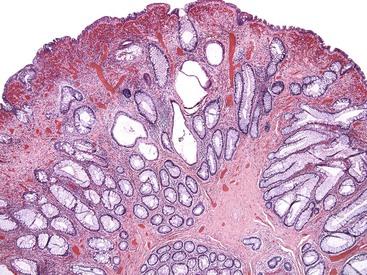

Pathologic Features

Polyps in Cronkhite-Canada syndrome occur throughout the GI tract but spare the esophagus. Histologically, in the colon, they closely resemble juvenile polyps, with cystically dilated, tortuous crypts containing inspissated mucin (Fig. 22.16). The intervening lamina propria is edematous and contains increased numbers of mononuclear cells and eosinophils. Burke and Sobin compared the histology of Cronkhite-Canada polyps with that of juvenile polyps.114 The histologic features of each type are microscopically indistinguishable, although colonic juvenile polyps are more frequently pedunculated.114 However, in patients with Cronkhite-Canada syndrome, the intervening nonpolypoid intestinal mucosa shows pathologic changes such as edema, cystically dilated glands, and increased inflammatory cells (see Fig. 22.16), whereas the intervening mucosa in JPS is normal.

Natural History and Treatment

The malignant potential of colonic Cronkhite-Canada polyps is controversial. There have been multiple reports of affected patients who have also had adenoma,115–117 colorectal carcinoma,116–118 or gastric cancer.118 Although some authors indicate that dysplastic changes may occur within the polyps,116,118,119 it is not clear whether these might represent separate incidental adenomas. The mortality rate in Cronkhite-Canada syndrome is high (50% to 60%). Death usually results from malnutrition, GI bleeding, or infection. Treatment includes aggressive nutritional support, antibiotics, corticosteroids, and surgical resection of symptomatic segments of the GI tract.112

Epithelial Polyps

Hyperplastic and Serrated Polyps

The classification of hyperplastic and serrated polyps used in this chapter reflects the one proposed by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2010.120 Hyperplastic polyps are the most common type of polyps in the colon. Recognized by their bland cytology and serrated architecture, these polyps were traditionally considered non-neoplastic lesions with no malignant potential. However, it is now recognized that some types of hyperplastic polyps may progress to malignancy.121,122 For instance, some hyperplastic polyps may grow to large sizes; many show abnormal proliferation and maturation, particularly in the right colon; and may be sessile (i.e., sessile serrated adenoma/polyp, discussed later).123–125 Recognition of the potential neoplastic nature of these latter lesions has led to identification of the serrated pathway of carcinogenesis,126–131 which is discussed further in Chapter 27. This carcinogenetic scheme implies that hyperplastic or hyperplastic-like polyps (collectively referred to as “serrated” polyps) may progress to dysplastic serrated polyps, and ultimately to adenocarcinomas, which often show high levels of microsatellite instability (MSI-H).131

Early steps in the serrated pathway of carcinogenesis involve a decrease in the rate of cell death (apoptosis), which leads to prolonged cell life, and an increase in the number of epithelial cells, which is believed to contribute to the serrated phenotypic growth pattern of the polypoid lesions.132 These polyps, for unknown reasons, have a higher susceptibility to DNA methylation, particularly in foci of DNA that are rich in cytosine-guanine dinucleotides, such as in the promoter regions of many tumor suppressor genes.133 Methylation of these areas, termed the CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP), may lead to transcriptional silencing of the promoters of tumor suppressor genes. For instance, silencing of the MLH1 gene, which produces a DNA mismatch repair protein, may lead to high levels of microsatellite instability and MSI-H cancers. Hypermethylation is present in as much as 40% of colon cancers. In approximately one third of hypermethylated cancers, inactivation of MLH1 has occurred; this results in accumulation of DNA microsatellite repeat sequences. Mutation of the BRAF gene is a characteristic feature of early serrated polyps and some types of hyperplastic polyps.123,129 Interestingly, distally located hyperplastic polyps do not often show methylation of MLH1 and typically have a low level of microsatellite instability (MSI-L).134 In fact, distal serrated or hyperplastic lesions may show methylation of the MGMT gene instead.

Further evidence of the serrated pathway of carcinogenesis is based on many reports of adenocarcinoma associated with so-called giant or large hyperplastic polyps.135 Furthermore, patients with multiple hyperplastic or serrated polyps (serrated polyposis syndrome [SPS]) have a markedly increased risk of adenocarcinoma.135,136 A large series of 90 MSI-H right-sided colorectal cancers120,137 showed a high association with atypical, large, and unusually shaped hyperplastic polyps (subsequently termed sessile serrated adenoma/polyps, or SSA/Ps [see later discussion]). There is also growing evidence to suggest that the risk of progression to cancer is determined by the size, location, and number of hyperplastic polyps rather than the specific morphologic subtypes.122,138 For instance, it appears that left-sided hyperplastic polyps in general contain far less malignant potential than large right-sided polyps, which have a higher rate of progression to carcinoma.139

Nondysplastic Serrated Polyps

The terminology and classification of serrated colonic polyps is controversial. The scheme used here, and outlined in Box 22.1, is based on the most recent WHO classification. It is clinically relevant and is focused on separating dysplastic from nondysplastic lesions.120 The growth pattern (architecture) and proliferative characteristics are also important parameters to evaluate in distinguishing these polyps. An excellent review on serrated lesions of the colorectum was published by Rex and colleagues in 2012.140

Hyperplastic Polyp

Clinical Features.

“Traditional” hyperplastic polyps are serrated polyps with normal architecture and proliferative characteristics. They are small, innocuous lesions that may be found throughout the colon of adults but are especially common in the rectum.123 As much as 90% occur in the left colon. The prevalence rate increases with age. As much as 35% of asymptomatic individuals older than 50 years of age demonstrate hyperplastic polyps.123 Specific lifestyle and dietary factors commonly associated with adenomas are also associated with hyperplastic polyps. These include cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, low folate intake, and obesity.141,142 These lesions are typically asymptomatic and are often identified as an incidental finding during endoscopic examination of the colon. Endoscopically, hyperplastic polyps are small, sessile, smooth bumps or nodules that appear pale and flatten on insufflation of air.143 In some instances, these lesions cannot be distinguished with certainty from adenomas endoscopically; therefore, patients typically undergo biopsy and fulguration.

Classification and Pathogenesis.

In a study by Torlakovic and co-workers, small left-sided “hyperplastic” polyps were classified into three general types based on their morphologic growth pattern and lack of proliferative or maturation abnormalities—the microvesicular, goblet cell, and mucin-poor types122 (Tables 22.4 and 22.5). These polyps are normally smaller than 0.5 cm and show crypt epithelial serration but do not possess the architectural and proliferative abnormalities of large atypical hyperplastic polyps (SSA/Ps). The microvesicular type is the most common and correlates with lesions considered by most pathologists to represent a typical hyperplastic polyp. It is believed that these polyps develop as a result of increased crypt epithelial cell turnover combined with delayed maturation from the crypt bases to the surface of the mucosa. Because of decreased apoptosis and a slower rate of surface cell exfoliation, these lesions acquire a hypermature appearance and their characteristic histologic serration. Crypt cell kinetic studies have shown that hyperplastic polyps do not, in fact, exhibit epithelial cell hyperplasia. These polyps, at least the microvesicular type, contain various genetic and cell cycle regulatory defects, and this has led to the belief that these lesions have malignant potential.122,124,129,144 Some authorities assert that some SSA/Ps arise from microvesicular hyperplastic polyps, but this belief is controversial. Hyperplastic polyps have also been shown to demonstrate dysregulation of cell proliferation; altered BCL2 and BAX gene expression; loss of heterozygosity (LOH) of chromosome 1p, the APC gene, chromosome 3p, and CDKN2A; TP53 overexpression; a high frequency of KRAS mutations; and altered CDKN1B expression.145–150 A variety of biochemical and oncofetal blood antigen expression patterns are altered in hyperplastic polyps as well.

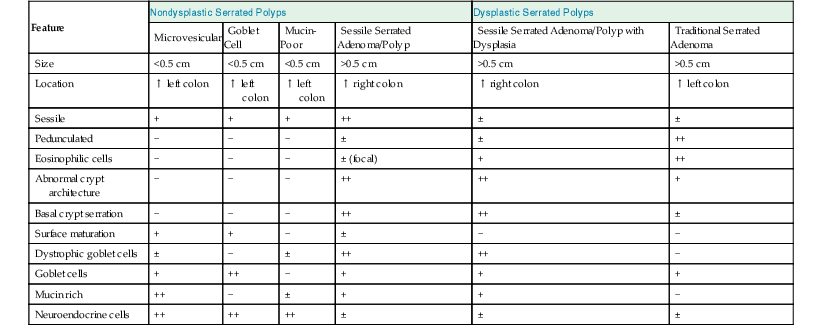

Table 22.4

Pathologic Features of Serrated Colonic Polyps

| Feature | Nondysplastic Serrated Polyps | Dysplastic Serrated Polyps | ||||

| Microvesicular | Goblet Cell | Mucin-Poor | Sessile Serrated Adenoma/Polyp | Sessile Serrated Adenoma/Polyp with Dysplasia | Traditional Serrated Adenoma | |

| Size | <0.5 cm | <0.5 cm | <0.5 cm | >0.5 cm | >0.5 cm | >0.5 cm |

| Location | ↑ left colon | ↑ left colon | ↑ left colon | ↑ right colon | ↑ right colon | ↑ left colon |

| Sessile | + | + | + | ++ | ± | ± |

| Pedunculated | − | − | − | ± | ± | ++ |

| Eosinophilic cells | − | − | − | ± (focal) | + | ++ |

| Abnormal crypt architecture | − | − | − | ++ | ++ | + |

| Basal crypt serration | − | − | − | ++ | ++ | ± |

| Surface maturation | + | + | − | ± | − | − |

| Dystrophic goblet cells | ± | − | ± | ++ | ++ | − |

| Goblet cells | + | ++ | − | + | + | + |

| Mucin rich | ++ | − | ± | + | + | − |

| Neuroendocrine cells | ++ | ++ | ++ | ± | ± | ± |

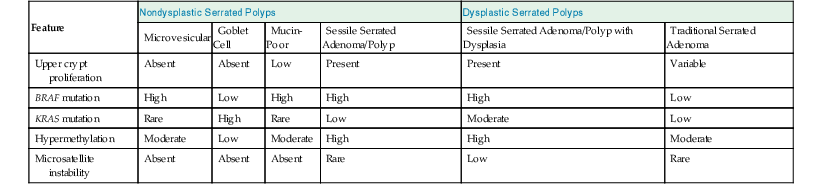

Table 22.5

Molecular Features of Serrated Colonic Polyps

| Feature | Nondysplastic Serrated Polyps | Dysplastic Serrated Polyps | ||||

| Microvesicular | Goblet Cell | Mucin-Poor | Sessile Serrated Adenoma/Polyp | Sessile Serrated Adenoma/Polyp with Dysplasia | Traditional Serrated Adenoma | |

| Upper crypt proliferation | Absent | Absent | Low | Present | Present | Variable |

| BRAF mutation | High | Low | High | High | High | Low |

| KRAS mutation | Rare | High | Rare | Low | Moderate | Low |

| Hypermethylation | Moderate | Low | Moderate | High | High | Moderate |

| Microsatellite instability | Absent | Absent | Absent | Rare | Low | Rare |

Little is known about the molecular characteristics of the mucin-poor type of hyperplastic polyp.122–124 However, goblet cell hyperplastic polyps typically show low levels of DNA methylation (CIMP) and absence or low levels of BRAF or APC mutations. In contrast, KRAS mutations have been identified in as much as 54% of cases, whereas TP53 is uniformly negative.144 In contrast, microvesicular hyperplastic polyps show DNA methylation (CIMP) in 68% of cases, and almost 80% show BRAF mutations.150 A small proportion show MGMT loss (14%). However, in contrast to goblet cell hyperplastic polyps, only a small proportion (4%) shows KRAS mutations.123,150 All three types of hyperplastic polyps are typically microsatellite stable.

There is abundant epidemiologic and morphologic evidence to suggest that hyperplastic polyps, at least the microvesicular type, may progress to carcinoma.123,129,151 Affected patients share risk factors with patients in whom colon cancer ultimately develops. Patients with hyperplastic polyps are also more likely to have adenomas than patients without these lesions. Foci with the appearance of microvesicular, or even goblet cell, hyperplastic polyps may be seen adjacent to, or within, portions of SSA/Ps, which are lesions considered to have higher malignant potential.130 On rare occasions, dysplasia, of either the conventional or the serrated adenomatous type, may be seen in association with microvesicular or even goblet cell hyperplastic polyps. Some traditional serrated adenomas (TSAs) show goblet cell hyperplastic polyp features in adjacent mucosa. Certainly, an increased risk of colon cancer has been detected in patients with SPS (see later discussion).

Pathologic Features.

Grossly, most hyperplastic polyps measure less than 0.5 cm. All types are characterized histologically by a “mature” appearance and display an irregular sawtooth or luminal serrated surface contour.122,150 This feature is most pronounced in the upper portions of the crypts but in some cases may also involve the middle and basal portions of the crypts. These polyps show simple tubular architecture without branching, budding, or crypt dilatation; they consist of either mature goblet cells or a combination of goblet cells and mucous cells. These lesions characteristically show proliferation (mitoses or Ki67 staining) limited to the lower half of the crypts. Most hyperplastic polyps also show increased numbers of neuroendocrine cells at the bases of the crypts.

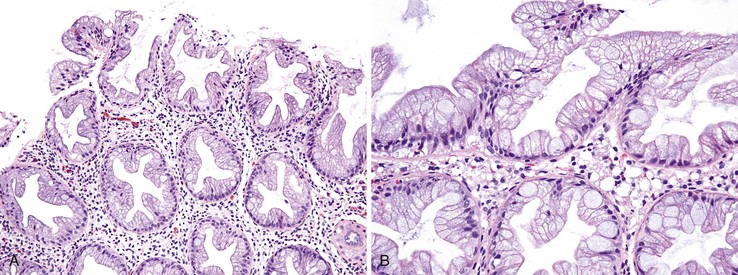

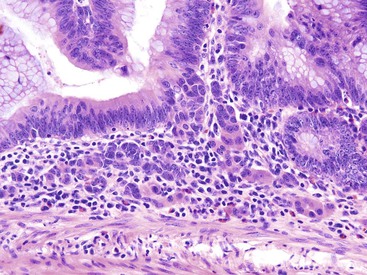

The microvesicular type of hyperplastic polyp is characterized by the presence of abundant (microvesicular) mucin and a paucity of goblet cells, compared with normal mucosa (Fig. 22.17). These lesions are more common in the left colon and are characterized by marked luminal serration and an expanded proliferative compartment that occupies most of the basal half of the crypts. Nuclear atypia is minimal, but some polyps show a mild degree of nuclear stratification at the base of the polyp. Dystrophic goblet cells and cells with round vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli are rare; if present, they are usually confined to the lower portions of the crypts. Most notably, these lesions show distinct evidence of surface maturation and absence of eosinophilic cytoplasm characteristic of TSAs (see later discussion). The superficial portion may show hypermucinous cells that may appear crowded focally. However, the cells maintain a mature appearance with small nuclei and absence of hyperchromasia or atypia. The deep regenerative portion of a microvesicular hyperplastic polyp may be confused with an adenoma because the cells may appear hyperchromatic compared with surrounding nonlesional colonic crypts. Nevertheless, the hyperchromatic regenerative zone maintains an orderly process of maturation to the surface, and this can be easily exemplified with the use of Ki67 or proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) staining. Some cases also show thickening and extension of the muscularis mucosae into the lamina propria.

Rarely, larger microvesicular hyperplastic polyps (>0.5 cm) may be slightly distorted or show mild crypt dilatation. In this instance, the features approach those of an SSA/P, and this has led some investigators to hypothesize that the microvesicular type of hyperplastic polyp is an early form of SSA/P. Both of these types of polyps show frequent BRAF mutations and DNA methylation abnormalities.150,152–154 Microvesicular hyperplastic polyps may, uncommonly, show misplacement of epithelium into the submucosa, but this is more common in SSA/Ps.122,155 This phenomenon has been termed inverted hyperplastic polyp, and it may be mistaken for an adenoma with epithelial misplacement or even an invasive adenocarcinoma. Some authorities have postulated that this phenomenon occurs as a result of trauma and subsequent protrusion of epithelium into the submucosa, similar to the pathogenesis of epithelial misplacement in adenomas.155

Goblet cell hyperplastic polyps are the second most common type of hyperplastic polyp. They are typically small (<0.5 cm), sessile lesions and are more commonly found in the left colon. These polyps show elongated crypts that are rich in goblet cells but without microvesicular mucin (Fig. 22.18). They are normally sessile but demonstrate a far lesser degree of luminal serration, which is often limited only to the surface and uppermost portions of the crypts. The crypts may be mildly elongated as well. Nuclear atypia, stratification, and mitoses are not seen in this type of hyperplastic polyp. KRAS mutations are common, but they only rarely show evidence of DNA methylation.144

Mucin-poor hyperplastic polyps are the least common type. Some authorities believe that they represent microvesicular hyperplastic polyps that have undergone irritation, mucin depletion, and inflammation as a result of injury or prolapse. These lesions are also sessile, but they exhibit small cells with less cytoplasm, micropapillary architecture, mucin depletion, absence of goblet cells, and a striking regenerative appearance (Fig. 22.19). The lack of mucin and the presence of hyperchromatic nuclei are the main features of these polyps. Inflammation in the lamina propria is characteristic. The molecular features of this subtype of hyperplastic polyp are poorly understood.

Differential Diagnosis.

Hyperplastic polyps should be differentiated from SSA/Ps, TSAs, prolapse-type inflammatory polyps, and conventional adenomas. In contrast to hyperplastic polyps, SSA/Ps show dilated crypts, prominent full crypt serration, basal crypt dilatation with horizontal and branched crypts, increased numbers of dystrophic goblet cells, focal nuclear stratification, and upper crypt mitoses. However, some microvesicular polyps may show one or more of these features focally; in these instances, correlation with the size, endoscopic appearance, and location of the lesion may be helpful. If the lesion is larger than 0.5 cm, sessile, and present in the right or transverse colon, it most likely represents an early SSA/P.

TSAs are usually easy to differentiate from hyperplastic polyps because the former are larger, are often villiform, and show marked cytoplasmic eosinophilia at all levels of the crypt. Nuclear stratification is typical.

Prolapse-type inflammatory polyps are frequently inflamed or even ulcerated. They may have superficial ischemic-type features, contain markedly regenerative epithelium, and show characteristic fibromuscular hyperplasia of the lamina propria.

Conventional adenomas have hyperchromatic, pseudostratified, cigar-shaped (pencillate), atypical nuclei. In adenomas with misplacement, the crypts also show atypical features, with frequent mitoses and even single-cell necrosis.

Natural History and Treatment.

Until recently, small hyperplastic polyps were not believed to require definitive treatment, although they are typically removed in the process of endoscopy with biopsy. However, the biologic characteristics and natural history of hyperplastic polyps, particularly the microvesicular type, are controversial. Certainly, large lesions that contain some features of SSA/Ps, particularly if they are located in the right colon, should be removed in total.124,140

Further studies are needed to determine the natural history and malignant potential of hyperplastic polyps and each of the different subtypes. There is a strong correlation between the occurrence of hyperplastic polyps and that of adenomas in similar populations in the world.156 Although some studies suggest that distally located hyperplastic polyps predict an increased risk of proximal adenomas, or even advanced adenomas, this idea is controversial,156–159 and at present, the finding of a distal hyperplastic polyp at sigmoidoscopy is not considered to be an absolute indication for full colonoscopy.123 Furthermore, surveillance for detection of metachronous hyperplastic polyps or adenomas after removal of hyperplastic polyps is not recommended.

Sessile Serrated Adenoma/Polyp

Clinical Features and Synonyms.

In contrast to left-sided “hyperplastic” polyps, right-sided “serrated” polyps are often larger (>0.5 cm) and sessile and contain significant architectural, proliferative, and maturation abnormalities.122,144 Crypt distortion and abnormalities in proliferative characteristics, such as asymmetry in proliferation and lack of a readily identifiable proliferative zone, are hallmarks of these lesions. Endoscopically, these lesions show a smooth surface contour, often covered with mucus.160 Some polyps show a characteristic pattern of orderly arranged circular dots similar to that of the surrounding normal mucosa; they can be identified and reliably distinguished from adenomas with a relatively high degree of accuracy by using high-resolution chromoendoscopy.160

There is ongoing debate regarding the terminology, diagnostic features, natural history, and risk of malignancy of this family of serrated polyps.124 Other commonly used terms to describe this lesion include atypical hyperplastic polyp, large hyperplastic polyp, hyperplastic polyp with architectural abnormalities, hyperplastic polyp with dysmaturation, and hyperplastic polyp with abnormal proliferation. However, based on the most recent edition of the WHO classification of digestive tumors, the recommended terms are sessile serrated adenoma or sessile serrated polyp (i.e., SSA/P). Both of these terms are considered acceptable in clinical practice. We prefer the term sessile serrated polyp (SSP) for several reasons, most importantly because most clinicians (and pathologists) associate the term “adenoma” with dysplastic changes that SSA/Ps do not possess until they become dysplastic.

As mentioned earlier, SSA/Ps show a high rate of DNA methylation (CIMP), approaching 92% in some studies, as well as BRAF mutations (80%), but a low prevalence of APC or KRAS mutations (<5%) and TP53 abnormalities.123,144,150,152,161 Microsatellite instability is not usually present until morphologic dysplasia, or carcinoma, has developed. Large lesions, or those with dysplasia, may also show loss of MLH1, MSH2, or MGMT, particularly in the left colon.130 Some studies have shown increased MUC2, MUC5AC, and MUC6 staining as well.

Pathologic Features.

Morphologically, SSA/Ps show distinctive features characterized by crypt dilatation, crypt irregularity (horizontally shaped crypts), prominent and often exaggerated lower (and upper) crypt serration, mitoses in the upper levels of the crypts, vesicular nuclei in the upper crypts, reduced amounts of lamina propria between crypts, hypermucinous epithelium, and, occasionally, an inverted (epithelial misplacement) growth pattern (Fig. 22.20; see Tables 22.4 and 22.5).122 The basal portion of the crypts are usually branched and appear flask or boot-shaped (similar to an inverted T), indicative of horizontal rather than vertical growth. Although their conclusion was controversial, a recent expert panel of pathologists suggested that the presence of one or more distorted crypts of this kind, at the base of the lesion, is enough evidence for diagnosis of an SSA/P rather than a hyperplastic polyp.120 These are sessile lesions, rich in mucin, and they contain round vesicular nuclei with prominent nucleoli. Mature goblet cells, or mucinous cells, show an irregular distribution by being uncharacteristically located at the bases of the crypts. Some polyps also show thickening of the basement membrane and perineurial-like proliferations in the lamina propria.162

SSA/Ps may show a variable degree of nuclear atypia. At the low end of the spectrum, lesions show little or no stratification, low mitotic rate, and evidence of surface maturation. At the high end, SSA/Ps may show an increased degree of nuclear stratification, consisting of cells with open vesicular chromatin and prominent nucleoli, increased eosinophilia of the cytoplasm (simulating the cellular appearance of a TSA), marked hyperserration, and lack of surface maturation. These features approach those of a serrated adenoma but without long filiform, or villous, projections. Often these lesions grow horizontally, and they may measure more than 1 to 2 cm. Some authors have referred to this lesion as advanced SSA/P, but this term actually refers to SSA/P with dysplasia (see later discussion) and is not recommended in clinical practice.

Dysplastic Serrated Polyps

Sessile Serrated Adenoma/Polyp with Dysplasia

With histologic and molecular progression (often characterized by loss of MLH1 immunostaining and microsatellite instability), SSA/Ps may acquire morphologic evidence of dysplasia that leads to a variable histologic appearance (see Tables 22.4 and 22.5).130,150,163 Histologically, these lesions have been referred to as “mixed hyperplastic/adenomatous polyps”; however, it is now well recognized that these polyps do not occur as a result of a coincidental growth of hyperplastic and adenomatous elements but as a result of dysplastic change within an SSA/P. Therefore, the term “mixed polyp” is not recommended. Morphologically, these lesions may show discrete areas of hyperplastic change typical of a microvesicular polyp, but more often they show features of an SSA/P combined with dysplasia (Fig. 22.21). Dysplastic changes often resemble a conventional adenoma, composed of elongated, cigar-shaped hyperchromatic nuclei with stratification and architectural serration. This is referred to as “intestinal-type” dysplasia. In some SSA/Ps, dysplastic changes show features of a TSA (“serrated dysplasia”), being composed of open, oval, or slightly elongated nuclei with prominent nucleoli, nuclear stratification, eosinophilic “pink” cytoplasm, and lack of surface maturation (Fig. 22.22). Some polyps may show a combination of conventional (intestinal) and serrated dysplastic features. Rarely, a combination of hyperplastic or SSA/P–appearing epithelium, dysplastic epithelium, and adenocarcinoma may be present in a single polyp.130

Natural History and Treatment.

The natural history and risk of progression to malignancy of SSA/P are poorly understood but are under intense investigation.124 It is commonly believed that loss of DNA repair ability and subsequent microsatellite instability are mechanisms that drive rapid neoplastic progression.150 Although SSA/Ps may contain dysplasia or even carcinoma, in most cases, the acquisition of dysplasia or carcinoma is related to the size of the lesion and take years to progress.140,164 Therefore, it is likely that the risk of progression to malignancy varies significantly with the size and location of the lesion. In one study of 55 patients with SSA/P who were monitored for a mean of 7 years, colorectal cancer or adenomas with high-grade dysplasia developed in 15% of patients. In other studies, patients with SSA/P were found to be at increased risk for synchronous advanced neoplasia and interval neoplasia during surveillance.165 Some recent studies have suggested that the potential for malignant transformation is similar to that of conventional tubular adenomas.140 Nevertheless, a rational proposal for the management of serrated polyps is based on the fact that most traditional hyperplastic polyps (goblet cell or microvesicular type) are unlikely to progress to carcinoma and that SSA/Ps without cytologic dysplasia are probably slow, but progressive, lesions.

Chapter 2 provides a summary of recommendations of surveillance intervals after endoscopic resection of serrated lesions. For SSA/Ps without dysplasia, complete endoscopic removal is warranted.123,124 However, if this is not possible, then repeat endoscopy with biopsies should be performed within 1 year to evaluate for signs of cytologic dysplasia, and this should be followed by continued surveillance at shorter intervals until the lesion is completely removed. Surgical excision for large SSA/Ps without dysplasia, particularly those that are recurrent, is also a reasonable alternative. Many investigators recommend surveillance every 5 years for SSA/Ps that are smaller than 10 mm in size; every 3 years for lesions that are larger than 10 mm as well as those that are smaller than 10 mm but multiple (three or more polyps); and every 1 to 3 years for lesions that are larger than 10 mm and multiple (two or more polyps) or for any polyp with dysplasia. In contrast, complete excision is considered mandatory for SSA/Ps with dysplasia, based on the likelihood that these lesions have undergone hypermethylation and microsatellite instability and therefore are prone to carcinoma progression. Complete excision should be accomplished by endoscopy or surgical resection. Patients usually undergo repeat endoscopy within 1 year to ensure that the lesion has been removed in its entirety and that there has been no progression.

Traditional Serrated Adenoma

TSAs are broadly defined as polyps that show a prominent serrated architectural growth pattern, a villiform (or filiform) growth pattern, and hypereosinophilic epithelium with phenotypic evidence of dysplasia, either low or high grade (see Tables 22.4 and 22.5).166–168 Although many lesions, in particular SSA/Ps (with or without dysplasia), have been referred to as “serrated adenomas,” TSAs are characterized by epithelium with confluent pink eosinophilic cytoplasm and a papillary, or villiform, growth pattern (Fig. 22.23). Because of confusion in the literature with regard to inclusion of different types of lesions within the TSA category, the clinical, epidemiologic, and molecular features of these uncommon lesions are poorly understood. Nevertheless, TSAs are uncommon, representing less than 1% to 2% of all colonic polyps in most studies. In one Japanese study, TSAs accounted for 1.8% of more than 10,000 colonic polyps.169 They are more common in females and occur much more commonly in the left colon,168 particularly the sigmoid and rectum.123 Right-sided lesions often represent SSA/P with exuberant and villiform serrated dysplasia. The mean age at diagnosis is 60 to 65 years, which is typically older than for patients with hyperplastic polyps or SSA/Ps.167

Endoscopically, TSAs manifest variable growth morphology and are more often pedunculated rather than sessile.168 In one study, 63% of TSAs were pedunculated, 29% were sessile, and 8% were described as flat or carpet-like.170 However, in SPS, TSAs are more common and may be seen in combination with hyperplastic polyps, SSA/Ps, SSA/Ps with dysplasia, and conventional adenomas.

The pathogenesis of TSAs is uncertain. Some studies suggest that they develop from precursor hyperplastic polyps (particularly the goblet cell type) or from SSA/Ps. However, other studies have failed to demonstrate this association and suggest that these lesions may develop via an alternate pathway. Methylation levels are intermediate between those of hyperplastic polyps and those of SSA/Ps, being present in approximately 65% of TSAs in one study, compared with 18% in conventional adenomas. In contrast, BRAF mutations are present in one third of cases. KRAS mutations have been identified in as much as 27% of TSAs, APC mutations in 5% to 28%, MGMT loss in 17% to 26%, and TP53 mutations in 10% to 20%.127,152,171–173 In one study, the prevalence of LOH of TP53, APC, 3p, and CDKN2A was low, similar to that for conventional adenomas.171 In a more recent study of 112 TSAs from Korea, one third of cases showed a hyperplastic or SSA/P precursor lesion, particularly in TSAs from the right colon. In that study, the presence of KRAS mutations and MGMT methylation was associated with an aggressive phenotype (high-grade dysplasia or carcinoma).174 Therefore, there is heterogeneity in the molecular pathogenesis of serrated adenomas.

Pathologic Features.

TSAs are characterized by prominent crypt serration with confluent epithelial dysplasia.150,168 These polyps are normally pedunculated and may occasionally be rather large and filiform.168 Filiform serrated adenomas show elongated, finger-like villous projections and often show inflammation, ulceration, and dilated lymphatics within the lamina propria (see Fig. 22.23). In one study, filiform serrated adenomas exhibited exclusive involvement of the rectum.168 The epithelium of serrated adenomas shows “dysplastic” characteristics, marked by nuclear atypia and nuclear stratification at all levels of the polyp, including the surface epithelium. Micropapillation of the surface epithelium and the presence of cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm are characteristic features.

The cells show a low N : C ratio with vesicular nuclei, an open chromatin pattern, and occasional inconspicuous nucleoli. These polyps are normally mucin depleted. The number of goblet cells may be variable. Dystrophic goblet cells are uncommon. On Ki67 or PCNA staining, the basal crypt compartment is often positive, but the luminal compartment is typically negative. Some TSAs, particularly those that are filiform, show abnormal horizontal crypt budding on the villi, which may be indicative of an abnormality in anchoring of the crypts to the basement membrane. This is referred to as “ectopic crypt formation.” Ectopic crypt formation is characteristic of TSA but is not specific, because it can also be seen in villous adenomas and in SSA/Ps with dysplasia.

On occasion, TSAs, particularly those that are large, show areas of conventional, adenoma-like, dysplastic foci within the lesion.130 It is likely that these lesions represent TSAs that have progressed, both morphologically and molecularly, along the APC/chromosomal instability carcinogenetic pathway, representing molecular heterogeneity within the polyp. TSAs may also show high-grade dysplasia (serrated or intestinal type, or both), characterized by increased cytologic atypia, marked stratification of nuclei, and a back-to-back epithelial growth pattern. Intraluminal “gland-in-gland” formation and cribriforming are common features of high-grade dysplasia.

Natural History and Treatment.

The natural history of TSA and the risk of progression to malignancy are poorly understood.123,174 Progression to high-grade dysplasia was reported in 37% of TSAs in one study.167 In that study, 11% contained intramucosal adenocarcinoma. In another study of filiform TSAs by Yantiss and colleagues, 22% showed high-grade dysplasia and another 6% showed invasive adenocarcinoma.168 In that study, 33% of polyps showed an adjacent region of hyperplastic or SSA/P morphology, indicating those areas as possible precursor lesions. It is possible that, as in other serrated polyps, loss of DNA repair mechanisms may drive rapid neoplastic progression.128 Some studies have suggested that the rate of malignant transformation is similar to that of conventional adenomas.169,173 However, it is likely that the risk of progression is related to the size and location of the lesion.169 Large TSAs in the proximal colon may progress at a more rapid rate than those in the left colon. The treatment of TSAs is similar to that of conventional adenomas. Complete endoscopic removal is warranted, and future surveillance intervals similar to those for patients with conventional adenomas (i.e., every 3 to 5 years) are recommended.

Conventional Adenoma with Serrated Architecture

Rarely, conventional tubular, tubulovillous, or villous adenomas show areas of architectural serration, but these polyps should be distinguished from TSAs by the cytologic features of the nuclei (Fig. 22.24).175 Conventional adenomas with architectural serration show elongated, cigar-shaped nuclei with clumped chromatin, nuclear stratification, and mucin depletion, resembling conventional adenomas that develop through the APC/chromosomal instability pathway. It is unclear why some conventional adenomas acquire a serrated growth pattern, but this may be related to the acquisition of KRAS mutations, which has been proposed to add a “serrated” molecular signature to traditional adenomas and provides evidence of a “fusion” molecular pathway of carcinogenesis in some cases.163 In fact, molecular alterations characteristic of both the serrated pathway and the chromosomal instability carcinogenetic pathway coexist in a minority of advanced colorectal polyps that display morphologic features of both lesions.174 In one study, these lesions accounted for only 2% of colorectal polyps but were postulated to have a higher degree of biologic potential.163

Unclassifiable Serrated Polyps