Polyps of the Esophagus

Audrey Lazenby

Introduction

Most types of inflammatory lesions of the esophagus do not manifest as endoscopically recognizable polyps. They instead cause only a slight mucosal irregularity or surface erosion. In contrast, most neoplastic processes of the esophagus manifest clinically at an advanced pathologic stage. Malignant tumors may form strictures, plaquelike masses, or deeply penetrating or fungating ulcers. Polyps, which are discrete, well-circumscribed luminal protrusions, are uncommon in the esophagus. However, many unusual types of tumors of the esophagus are polypoid.1 Although esophageal polyps are rare, they often have interesting or unusual pathology.

Esophageal polyps may be divided into epithelial and mesenchymal types. Each type can be further subdivided as benign or malignant. The epithelial nature of an esophageal polyp is usually apparent at endoscopy or on radiographic evaluation because of the formation of a mucosal irregularity. In contrast, most mesenchymal polyps originate within the subepithelial tissues, causing an endoscopically recognizable elevation of the overlying mucosa, but the latter is usually left intact with a smooth contour.

Epithelial Polyps

Small polyps covered by benign (non-neoplastic) squamous epithelium may develop anywhere in the esophagus (Table 19.1). The pathogenesis and morphologic features of these polyps tend to correlate roughly with their site of origin. The two main types of squamous polyps are inflammatory polyps and squamous papillomas.1

Table 19.1

Epithelial Polyps of the Esophagus

| Type of Lesion | Morphology and Stains | Comments |

| Benign | ||

| Inflammatory polyp | Irregular tongues of squamous mucosa | GEJ, reflux related |

| Hyperplastic polyp | Foveolar hyperplasia | GEJ |

| Gastric heterotopia | Glands and foveolar epithelium | Proximal esophagus |

| Glycogenic acanthosis | Larger clear squamous cells, PAS+ | Increased intracellular glycogen level If numerous, consider Cowden syndrome |

| Adenoma | Tubular, cystic papillary growth in submucosa | Arises from submucosal glands or ducts; rare |

| Malignant | ||

| Polypoid dysplasia | Resembles colonic adenoma | Setting of Barrett’s esophagus |

| Spindle cell carcinoma | Biphasic, squamous and spindle cells; keratin+ | Better prognosis than conventional SCCA |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | Usually strictured, ulcerated or fungating mass | Rarely polypoid |

| Adenocarcinoma | Usually strictured, ulcerated or fungating mass | Rarely polypoid |

| Melanoma | Melan-A+, S100+ | Primary and metastatic |

GEJ, Gastroesophageal junction; melan-A, melanoma antigen recognized by T cells 1 (MART1); PAS, periodic acid–Schiff stain; SCCA, squamous cell carcinoma.

Inflammatory and Hyperplastic Polyps

Inflammatory polyps are the most common type of benign, squamous esophageal polyp. They occur primarily in men at the lower esophageal junction and usually are associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).2–4 Inflammatory polyps represent an exaggerated response to mucosal injury. Some are exuberant, healed ulcer sites. Inflammatory polyps may also develop proximal to the gastroesophageal junction, where they are often associated with mucosal injury caused by embedded pills, infection, or surgical anastomoses.5

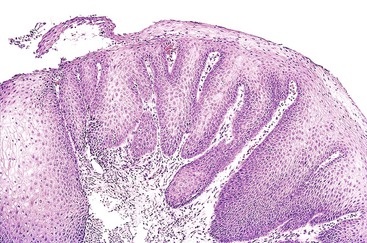

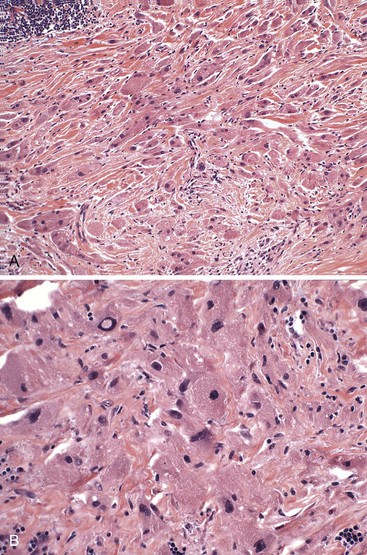

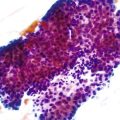

Histologically, inflammatory polyps often have a smooth, rounded surface and consist of irregular tongues of squamous epithelium that extend deeply within an inflamed lamina propria (Fig. 19.1). Although controversial, some investigators think these polyps represent an endophytic type of squamous papilloma.6 Human papillomavirus (HPV) was identified in 33% of these polyps by polymerase chain reaction analysis in a study by Odze and colleagues.6 HPV was postulated to be a promoter of epithelial growth in mucosa that had been damaged by other irritants such as GERD.6

At the level of the gastroesophageal junction, hyperplastic polyps composed primarily of gastric hyperplastic foveolar epithelium, with or without hyperplastic and regenerative-appearing squamous epithelium, can develop, presumably as a result of chronic mucosal injury.5 These gastroesophageal junction polyps have been most often reported in the clinical gastroenterology or radiology literature.7 Hyperplastic polyps at the gastroesophageal junction may be associated with a short or ultrashort Barrett’s esophagus (33% of cases), and they have less inflammation compared with those arising in a non-Barrett’s setting.8

Squamous Papilloma

Squamous papillomas are the other main type of squamous polyp of the esophagus (see Chapter 24).9 They are the most common benign tumor of the esophagus.1,6 In an upper gastrointestinal (GI) screening study from Korea, squamous papillomas were detected in 0.31% of patients.9 Other studies suggest that these lesions are underdiagnosed.

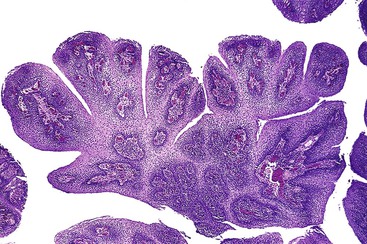

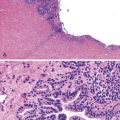

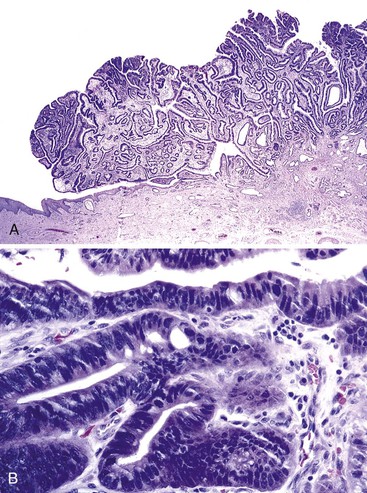

Two or three main histologic patterns have been described: exophytic, endophytic, and spiked.6 The exophytic type is more common. On endoscopy, these lesions have a cauliflower-like appearance. Histologic examination of the exophytic type reveals finger-like squamous papillae overlying fibrovascular cores of lamina propria (Fig. 19.2). The squamous epithelium may have features of koilocytosis, but it usually lacks the large, hyperchromatic nuclei and binucleation typical of human papillomavirus (HPV)–infected cervical epithelium. Exophytic squamous papillomas occur most frequently in the distal esophagus, but they also occur in the middle and upper esophagus. HPV is associated with as many as 78% of these squamous papillomas.6,10

The endophytic type of papilloma has a round, smooth surface and an inverted papillomatous appearance. Some investigators think they are inflammatory polyps. Spiked squamous papillomas have a verrucous appearance, a corrugated surface, hyperkeratosis, and a prominent granular cell layer. This is the least common form of squamous papilloma. Forty percent of spiked papillomas were shown to harbor HPV in one study.6 Ratoosh and co-workers described a 60-year-old woman who had a large, verrucous lesion of the distal esophagus and multiple warts on her distal fingertips.11 HPV-45 DNA sequences were identified in the fingertip and esophageal verrucous lesions, suggesting autoinoculation of the finger wart HPV virus to the esophagus.11

Squamous papillomas are benign. Rarely, large squamous papillomas have undergone malignant degeneration.12 However, whether these lesions represent de novo carcinomas or true malignant degeneration of a squamous papilloma is unknown.

Heterotopia

Several types of esophageal heterotopias rarely manifest as polypoid lesions on endoscopy (see Chapter 24). Heterotopias occur in 10% of the general population and usually consist of gastric heterotopia, although thyroid, parathyroid, and ectopic sebaceous tissues have been described.13 Gastric heterotopias in the esophagus usually contain glands and foveolar epithelium (82% of cases) and are thought to be congenital in origin.14 Heterotopias are often found in the proximal esophagus and may be called an inlet patch on endoscopy.

Glycogenic Acanthosis

Small, plaquelike or nodule-like lesions can occur in patients with prominent glycogenic acanthosis. It represents focal nodular thickening of the squamous mucosa with cells that contain prominent intracytoplasmic glycogen. Endoscopically, the lesions can resemble squamous papillomas. Patients with Cowden syndrome or tuberous sclerosis may have numerous polypoid areas of glycogenic acanthosis, and this finding always raises the possibility of one of these diagnoses.15,16

Adenomas

True adenomas of the esophagus are rare (see Chapter 24). Most commonly, they develop from the submucosal gland or duct system and show a mixture of tubal, cystic, and papillary growth patterns that are similar to those of intraductal papillomas of the breast or sialadenoma papilliferum of the salivary glands. Most of these tumors are benign, but rare cases of malignant transformation have been described.

Polypoid Dysplasia in Barrett’s Esophagus

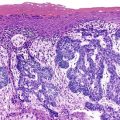

Most so-called adenomas reported in the earlier literature are instead polypoid areas of dysplasia arising in Barrett’s esophagus (Fig. 19.3) (see Chapter 24). In one series, dysplasia was polypoid in 2% of a series of Barrett’s patients with dysplasia.

Grossly, they resemble colonic adenomas, which led investigators to label them as adenomas. However, polypoid dysplasia arising in Barrett’s esophagus has clinical, pathologic, and molecular features similar to those of flat dysplasia and should not be considered benign lesions that can be excised without further follow-up. In one study, all adenoma-like polypoid areas of dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus were associated with carcinoma. Because the term adenoma often implies a relatively benign natural history, we recommend that this term for dysplastic lesions be replaced with polypoid dysplasia arising in Barrett’s esophagus.17,18

Spindle Cell Carcinoma

Spindle cell carcinoma (also referred to as carcinosarcoma, pseudosarcoma, polypoid carcinoma, sarcomatoid carcinoma, and spindle cell variant of squamous cell carcinoma) is a rare type of malignant tumor that represents 2% of all esophageal carcinomas (see Chapter 24).19,20 Spindle cell carcinomas are bulky, intraluminal masses with exophytic growth that most often develop in the middle portion of the esophagus of middle-aged to elderly men (80%).21,22 The most common presenting symptom is dysphagia, followed by weight loss and pain.21

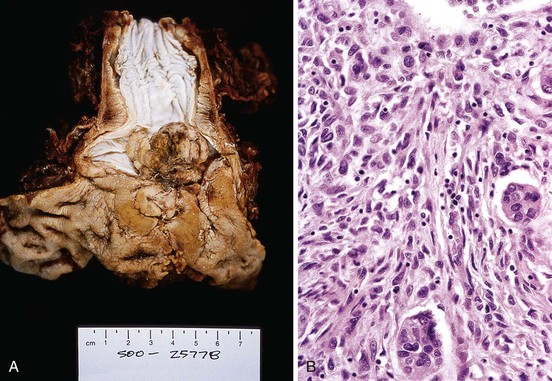

Typical radiologic features include a dilated esophagus expanded by a polypoid, bulky mass with a smooth or scalloped margin. The classic radiologic appearance has been referred to as a cupola sign.20,22 Histologic examination of these tumors reveals a biphasic growth pattern, showing areas of carcinoma (well, moderately, or poorly differentiated) and areas of malignant, undifferentiated spindle cells.

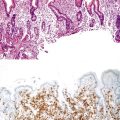

The epithelial origin of spindle cells has been confirmed by immunohistochemistry, electron micrographic studies, and genetic studies that have shown similar TP53 mutations in the sarcomatous and carcinomatous components.1,23,24 The mesenchymal component may show liposarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, or osteosarcoma differentiation. Many previously reported primary soft tissue sarcomas of the esophagus probably instead represent spindle cell carcinomas with a predominant undifferentiated soft tissue sarcoma component. The carcinomatous component is usually squamous, but rarely it can have adenocarcinomatous elements (Fig. 19.4).25

Most cases have squamous dysplasia in the overlying or adjacent mucosa, but this finding can be focal and difficult to detect if only a limited number of tissue sections have been obtained. The carcinomatous component may exist only at the base of the polyp and is often overgrown by the more exuberant spindle cell component. Lauwers and colleagues showed that the spindle cell component possessed a greater proliferative index and increased aneuploidy compared with the carcinomatous elements, perhaps providing it with a growth advantage.26

Metastases may be composed of either or both of the cellular components. Because these tumors demonstrate prominent exophytic growth with less extension into the esophageal wall, they have been associated with relatively good survival rates. In some studies, 50% to 60% of affected patients are alive after 5 years.1

Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Adenocarcinoma

In the United States, most squamous cell carcinomas and adenocarcinomas of the esophagus are detected at an advanced stage and grow in the form of strictures, irregular masses, ulcers, or fungating masses. Only approximately 15% of all esophageal malignancies grow in a polypoid fashion, and most of these are spindle cell carcinomas.22 Conventional squamous cell carcinoma, small cell carcinoma, and adenocarcinoma are only rarely polypoid. Occasionally, early-stage squamous cell carcinomas or high-grade dysplastic lesions may grow as an endoscopically detected polypoid lesion.27

Melanoma

Primary malignant melanomas of the esophagus are rare, but some have been reported to grow as a polypoid mass.28 These tumors may or may not be pigmented and show a range of histologic patterns, including epithelioid and spindle cell elements.29 Metastatic melanoma may also have a polypoid growth pattern. Differentiation of primary from metastatic melanoma relies on the demonstration of junctional melanocytic activity in the esophageal mucosa30 and on the absence of melanoma elsewhere in the body.31

Mesenchymal Polyps

Granular Cell Tumors

Granular cell tumors are benign tumors of Schwann cell origin (Table 19.2). They may develop anywhere in the body but occur most commonly on the skin or the tongue. The GI tract is a relatively uncommon site for the development of granular cell tumors, but within that organ system, the esophagus is the most common location. Granular cell tumors occur primarily in adults (median age, 46 years), are more common in women than men, and are more common among blacks than whites, particularly in the United States. Patients with a granular cell tumor are usually asymptomatic. Most cases are detected incidentally at the time of upper endoscopy.32–35

Table 19.2

Mesenchymal Polyps of the Esophagus

| Type of Lesion | Morphology and Stains | Comments |

| Benign | ||

| Granular cell tumor | Abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, pyknotic nuclei, S100+, PAS+ | Beware of overlying pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia |

| Leiomyoma | Spindle cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, actin+, CD117−, rare mitotic figures | Small, firm, usually in muscularis propria; rarely polypoid, arising in muscularis mucosae |

| Fibrovascular polyp | Large, sausage-shaped polyp with fibrovascular core | Upper esophagus, dysphagia, may flip into airways and asphyxiate patient |

| Malignant | ||

| GIST | Spindled or epithelioid, minimal cytoplasm, CD117+, mitotic figures | Large, soft, 50% malignant |

| Leiomyosarcoma | Atypical nuclei, eosinophilic cytoplasm, actin+, CD117− | Rare |

GIST, Gastrointestinal stromal tumor; PAS, periodic acid–Schiff stain.

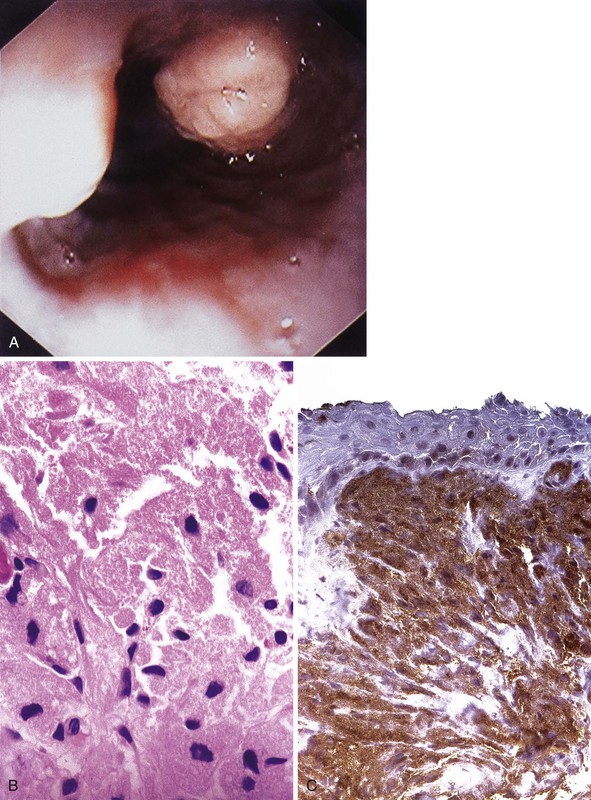

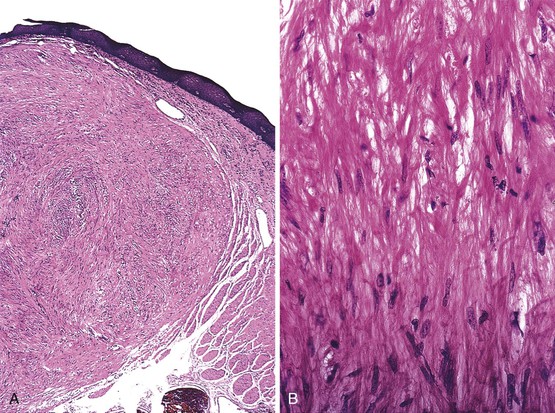

On endoscopy, granular cell tumors appear as yellow or yellow-white submucosal lesions that are firm to the touch (Fig. 19.5A).36 These tumors are most common in the distal esophagus, and they are usually single but can be multiple. Voskuil and co-workers found that 95% of granular cell tumors were single and 75% occurred in the distal esophagus.34 In this study, most tumors were small; 50% measured less than 5 mm, 25% measured 5 to 10 mm, and 18% measured 10 to 30 mm in the greatest dimension.34 At presentation, some patients had dysphagia, particularly those with large tumors.

Histologically, granular cell tumors are composed of sheets or nests of cells with abundant eosinophilic granular cytoplasm and small, pyknotic nuclei (see Fig. 19.5B). They are most common in the superficial lamina propria but may rarely involve the submucosa or muscularis. The cytoplasmic granules correspond to autophagic vacuoles filled with myelin-like debris, as documented by electron microscopy. For unknown reasons, the squamous epithelium overlying granular cell tumors often has marked pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia that may mimic dysplasia or carcinoma.32 Because these tumors are subepithelial, superficial biopsies may not reveal diagnostic tumor tissue. Granular cell tumors are typically periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) stain and S100 protein positive (see Fig. 19.5, C).33

Although most granular cell tumors are small and limited to the lamina propria, rare cases may involve the submucosa or muscularis propria.33,37 Deep, infiltrative-appearing growth may prompt concern about malignancy; however, malignant behavior is rare. In one patient with a granular cell tumor with an infiltrative growth pattern that was initially diagnosed as malignant, the tumor was incompletely resected, but the patient was reported to be alive and well after 22 years of follow-up. This case suggests that an infiltrative growth pattern does not necessarily imply malignancy.38

Examination of malignant esophageal granular cell tumors reveals atypical cytologic features, including large nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and occasional mitotic figures (Fig. 19.6). These features have been cited as evidence for malignancy.33 Fewer than 10 cases of presumed malignant granular cell tumors of the esophagus have been reported, but the pathologic features were not well defined.33,39 Ultimately, malignancy is confirmed by identification of metastasis. Only a few of these presumed malignant granular cell tumors have lymph node metastases, and none of the patients died of the disease. True malignant esophageal granular cell tumors are rare.

Leiomyomas

Leiomyomas are the most common type of mesenchymal tumor of the esophagus (see Chapter 30). In autopsy studies, as many as 8% of patients harbored at least one esophageal leiomyoma.40,41 However, leiomyomas detected at autopsy are usually minute. In a Japanese study, esophageal leiomyomas had a mean size of 2.5 mm in the greatest dimension and were often multiple. Leiomyomas occur equally in men and women and are usually single, although 24% of patients have multiple lesions. Multiple lesions have been called seedling leiomyomas.41

Most leiomyomas are located within the inner layer of muscularis propria. However, as many as 18% occur within the muscularis mucosae.41 Of 48 esophageal leiomyomas collected in one study from the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology and the Haartman Institute in Helsinki, 79% were located in the distal esophagus, 18% in the midesophagus, and 3% in the proximal esophagus.

Multiple, large leiomyomas in the distal esophagus have been called leiomyomatosis. Leiomyomas may occasionally grow large, measuring as large as 10 cm in one series.42 Massive leiomyomas (>1000 g) have rarely been reported.43 Symptoms related to the tumor, most commonly dysphagia, may develop in patients with large leiomyomas.42 Most leiomyomas have an intramural location, but in one series, 3% were polypoid.40 Endoscopic ultrasound is useful for detection and localization of esophageal leiomyomas.43 Small, pedunculated leiomyomas localized to the muscularis mucosae may be resected endoscopically.44

Grossly, esophageal leiomyomas are gray-tan lesions with a firm consistency. Examination usually reveals a cut surface with a whorled appearance similar to their uterine counterpart. Histologically, leiomyomas have low cellularity and are formed of bland-appearing eosinophilic spindle cells with bland, slightly oval nuclei and no or minimal mitotic activity (Fig. 19.7). The cells resemble closely the normal fibers of the muscularis, but they are arranged in an irregular fashion and associated with small, thin-walled blood vessels.

Immunohistochemical analysis can confirm the smooth muscle nature of the tumor. These tumors are universally positive for actin, desmin, and high-molecular-weight caldesmon. Immunohistochemical staining for CD117 (KIT) is negative in all cases.45

Giant Fibrovascular Polyps

Fibrovascular polyps are rare lesions, but because of their often large size and upper esophageal location, affected patients may have a dramatic clinical presentation. In one series of 16 cases from the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, the mean age at presentation was 56 years (range, 32 to 89 years). Men and women were affected equally.46

These polyps typically occur in the proximal esophagus at the level of the cricopharyngeus muscle.43 Large polyps may obstruct the lumen of the distal esophagus or cause asphyxia because of compression of the larynx or regurgitation into the posterior pharynx. Radiologically, the large, sausage-shaped polyps often are easily demonstrated on barium swallow studies.46 Although most patients have slowly evolving and progressive dysphagia, some have acute respiratory distress or asphyxiation at presentation. Respiratory problems may be caused by obstruction of the upper airways, particularly when patients vomit, belch, or cough.47

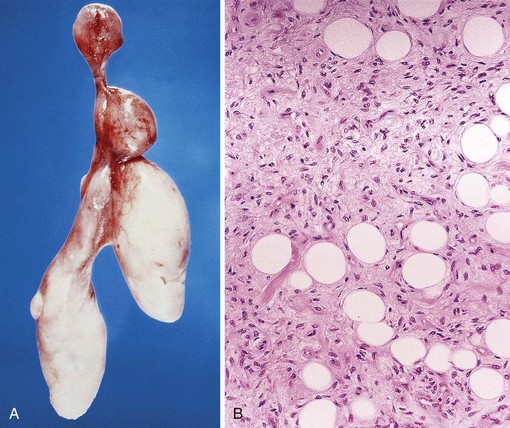

Pathologically, fibrovascular polyps are elongated tubular structures (up to 15 cm long) covered by benign, often reactive squamous epithelium that may or may not have surface erosion or ulceration (Fig. 19.8, A). Histologically, the core of fibrovascular polyps consists of loose, myxoid, hyalinized or collagenous fibrous tissue with various amounts of adipose tissue, edema, and inflammatory cells. Scattered, enlarged, reactive mesenchymal fibroblasts and myofibroblasts are typical. Lesions usually are quite vascular, with a mixture of small- and medium-caliber venous and arterial structures (see Fig. 19.8, B).48 Because of the considerable degree of adipose tissue in some cases, some have been erroneously reported as lipomas or fibrolipomas.43

The pathogenesis of fibrovascular polyps is unknown. One theory proposes that they develop as a result of prolapse or redundant folds of mucosa, resulting from excessive swallowing pressure forces. The Laimer triangle, which is located just below the cricopharyngeal muscle, is a region of relative muscular deficiency that has been proposed as the site of origin for these polyps.49 Although no molecular studies have been performed, most authorities think the polyps are reactive in nature and do not represent a true neoplasm. The absence of MDM2 gene amplification allows distinction from atypical lipomatous tumor, for which it can be mistaken.

Rare Benign Polyps

Rarely, inflammatory fibroid polyps have been reported in the esophagus.50 Other rare mesenchymal polyps of the esophagus include inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor,51 hemangioma,52 and bacillary angiomatosis.53 Bacillary angiomatosis was reported in the esophagus of a patient after exposure to cats.53 It manifested as multiple, friable, polypoid lesions in the esophagus.

Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are most common in the stomach, followed by the small bowel and the colon, particularly the rectum.54–56 These tumors rarely arise in the esophagus.45 In a study by Miettinen and co-workers, esophageal GISTs developed primarily in older patients (median age, 63 years), typically in the lower esophagus, and most patients had dysphagia at presentation.54 Most esophageal GISTs had an intramural location. However, 17% had an intraluminal polypoid growth pattern.

Gross examination of esophageal GISTs reveals a soft, fish-flesh appearance and areas of necrosis. Histologically, most are composed of pure spindle cells, but as many as 25% also have a mixture of epithelioid cells. The appearance of esophageal GISTs ranges from confluent sheets of cells to areas with neuroid-type nuclear palisading to foci with marked myxoid stroma.

Unlike most gastric GISTs, more than 50% of esophageal GISTs are malignant. In the study by Miettinen and associates, most malignant GISTs were larger than 5 cm in the largest dimension, contained more than 15 mitotic figures per 50 high-power fields, and had foci of necrosis.45

Esophageal GISTs are usually easily differentiated from esophageal leiomyomas grossly and microscopically. Leiomyomas are small, well-circumscribed, firm lesions. They are paucicellular, amitotic, and non-necrotic. GISTs are usually larger, soft, and significantly cellular. Mitoses and necrosis are common. Immunohistochemical studies are typically diagnostic, because most GISTs are CD117 and DOG1 (now designated ANO1) positive, desmin negative, and usually smooth muscle actin negative. Leiomyomas have the opposite immunophenotype.

Cystic and Diverticular Lesions

Esophageal cysts and diverticula, which are predominantly mural lesions, may cause a smooth elevation of the overlying mucosa and manifest as polypoid lesions (see Chapter 8). Cysts that arise within the wall of the esophagus are rare. They include simple cysts, duplication cysts, and bronchogenic cysts.57–59 Simple cysts develop as a result of obstruction and dilation of the esophageal submucosal glands or ducts, or both. They are composed of flattened or atrophic, typically bilayered, cuboidal epithelium in which the lumen is filled with glandular secretions.

Duplication cysts are spherical structures located within the wall of the esophagus. Rarely, the duplicated segment may represent a separate cylindrical tube located parallel to the lumen of the esophagus. Duplication cysts are most frequently located in the distal esophagus and typically include all three layers of tissue (i.e., mucosa, submucosa, and muscularis). By definition, duplication cysts contain both layers of the muscularis propria, but the epithelial lining may be squamous or columnar or a mixture of both. Esophageal duplication cysts may be asymptomatic but can also cause obstructive symptoms, such as dysphagia or respiratory compromise.

Bronchogenic cysts occur in the mediastinum adjacent to the esophagus and often at the same location as esophageal duplication cysts. Bronchogenic cysts are discrete extrapulmonary structures lined by respiratory-type epithelium and contain cartilage remnants and seromucinous glands. The generic term foregut cyst may be used for either lesion.60,61

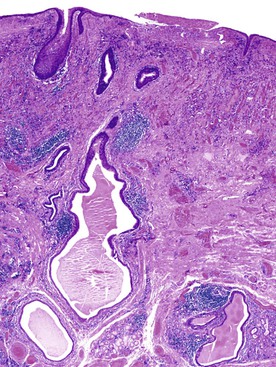

Esophageal pseudodiverticulosis is characterized by tiny, flask-shaped outpouchings in the wall of the esophagus. The outpouchings are dilated submucosal gland ducts that may contain inspissated mucin and inflammatory cells (Fig. 19.9). Most cases of pseudodiverticulosis manifest as strictures in the middle and upper esophagus of elderly individuals, and they rarely manifest as intraluminal masses.62