Chapter 546 Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Hirsutism

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

Etiology and Definition

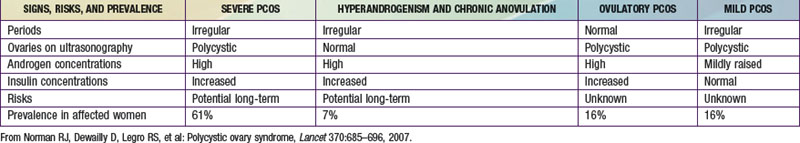

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a common disorder of reproductive hormone dysfunction, often with associated metabolic abnormalities, that affects 5-8% of women of reproductive age. The disorder typically emerges in adolescence when a normal menstrual pattern is not established and there is clinical evidence of androgen excess. It is characterized by the triad of oligo-ovulation or anovulation, clinical or biochemical hyperandrogenism, and ovarian cysts (≥12 immature follicles) (the Rotterdam criteria). Various expert bodies prioritize these elements differently for establishing the diagnosis, and few require the presence of all 3. Hyperandrogenism with ovulatory dysfunction (with exclusion of other causes) is most often considered sufficient for diagnosis in the USA. Abnormalities commonly associated with PCOS include obesity, insulin resistance, and the metabolic syndrome, but the phenotype is variable (see ![]() Table 546-1 on the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics website at www.expertconsult.com).

Table 546-1 on the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics website at www.expertconsult.com).

Pathology Pathogenesis and Genetics

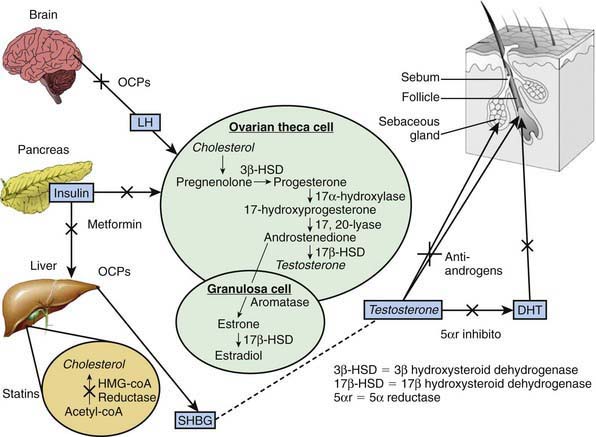

Gonadotropic dysregulation with increased luteinizing hormone (LH) pulsatility and abnormally high ratios of circulating LH to follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) are found in many patients with PCOS. Increased ovarian production of androgen in response to LH and impaired folliculogenesis owing to lower FSH are attributed to this gonadotropic pattern. Abnormal regulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist (GnRH) and abnormal gonadotropin secretion more likely reflect the abnormal hormonal milieu of the syndrome than explain its origin (Fig. 546-1). An increased ratio of circulating levels of LH to FSH is not a diagnostic criterion for PCOS.

Clinical Manifestations

PCOS commonly becomes manifest as puberty progresses, but its onset can occur later during young adulthood. PCOS is a lifelong disorder (though with some evidence for amelioration with age or weight loss) (Table 546-2). Clinical hallmarks are menstrual abnormalities and manifestations of hyperandrogenism. Ovulation is typically irregular or absent, and menses are consequently irregular or absent. When they do occur, menses may be relatively normal in character as a consequence of a preceding ovulation. In many women, protracted periods of unopposed estrogen exposure without ovulation can terminate erratically in bleeding that is abnormally prolonged and/or heavy.

| PRENATAL OR CHILDHOOD | ADOLESCENCE, REPRODUCTIVE YEARS | POSTMENOPAUSAL |

|---|---|---|

| REPRODUCTIVE | ||

From Norman RJ, Dewailly D, Legro RS, et al: Polycystic ovary syndrome, Lancet 370:685–696, 2007.

Laboratory Findings, Diagnosis, and Differential Diagnosis

The diagnosis of PCOS requires exclusion of disorders that would otherwise account for hyperandrogenism and anovulation. Serum 17-hydroxyprogesterone should be measured when there is clear androgen excess to screen for adult-onset 21-hydroxylase deficiency (Chapter 570). In the adolescent with amenorrhea but minimal hyperandrogenic findings, consideration should be given to functional hypothalamic suppression due to excessive exercise and/or dieting and a careful history taken to rule out such behavioral patterns. All patients should be clinically evaluated for Cushing syndrome, and biochemical evaluation is indicated when findings, including hypertension and/or characteristic body habitus features, are suggestive (Chapter 571). The two disorders have in common a tendency for overweight and varying degrees of insulin resistance and androgen excess, but they differ in that Cushing syndrome demonstrates muscle wasting as a result of catabolism.

Complications and Long-Term Outlook

Fertility management, prevention of endometrial cancer, and reduction in the likelihood and severity of the common accompanying metabolic disorders are long-term tasks for the PCOS patient and her health care providers (see Table 546-2). Notwithstanding its reversibility with weight loss in some patients and a tendency to ameliorate in some women later in reproductive life, PCOS usually requires management throughout the reproductive years. Young patients should be counseled that modern fertility management allows most affected women to have children without great difficulty, and they should also know that the disorder does not confer reliable protection from unintended pregnancy. Endometrial cancer can develop as early as the 3rd decade in women with PCOS who are not managed with progestins or ovulation induction; patients should understand the importance of long-term strategies for endometrial protection. Impaired glucose tolerance, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic syndrome are more common among obese adolescents with PCOS; their prevalence increases over time. Weight control through diet and lifestyle measures, detection and management of impaired glucose tolerance and diabetes, and management of abnormal lipids are targets for long-term management.

Treatment

Hormonal Contraceptives

Combined (estrogen and progestin) hormonal contraceptive medications are considered first-line therapy for adults not desiring fertility and for adolescents (Chapter 111). Adolescents with PCOS are at risk for unintended pregnancy; their fertility would be expected to be reduced relative to peers’, but they are still at risk for pregnancy.

Hirsutism

Hirsutism is defined as abnormally increased terminal (mature, heavy, dark) hair growth in areas of the body where hair growth is normally androgen dependent (Chapter 654). Its presence is a result of the combination of extent of androgenic stimulation and familial regional follicle sensitivity to androgens, which varies considerably among ethnic groups. Patients’ cosmetic concerns generally determine whether findings of hirsutism are a matter for clinical investigation and treatment. Hirsutism as an isolated finding is to be distinguished from masculinization. The latter includes alteration in muscle mass, clitoral enlargement, and voice change, generally manifesting as a rapid evolution (over months). Masculinization mandates a search for neoplastic source of androgen. Elevations of testosterone or DHEAS commonly indicate an ovarian or adrenal androgen source, respectively; specific imaging and occasionally selective catheterization studies are indicated.

Hirsutism without masculinization is common. The potential causes to consider are PCOS (when there is hyperandrogenism and anovulation), benign functional androgen excess (measurable hyperandrogenism without anovulation), idiopathic hirsutism (increased hair in androgen-dependent areas without measurable androgen excess), and adult-onset adrenal hyperplasia (Table 546-3). Patients can be primarily distinguished by evidence of ovulatory disorder by menstrual history, and for those with absent or irregular menses, a diagnosis of PCOS can be made. The remainder, for whom adult-onset adrenal hyperplasia and PCOS have been excluded, either have normal androgen levels with enhanced end-organ sensitivity owing to familial or ethnic predisposition or have a functional and benign overproduction of ovarian androgens. Measures of androgens (testosterone, DHEAS) may be normal or mildly elevated in the latter group. Testosterone suppresses circulating sex-steroid binding globulin, so that states of testosterone overproduction might not be accompanied by elevated measures of total testosterone although estimates of “free” or “bioavailable” testosterone reveal hyperandrogenism. Measures of unbound testosterone distinguish idiopathic hirsutism from mild benign hyperandrogenic states; making this distinction contributes little to patient management and adds cost. Idiopathic hirsutism (without evidence of androgen excess) usually responds to antiandrogen or androgen suppression therapy similarly to hirsutism associated with elevated androgens and anovulation (PCOS), and benign hyperandrogenism not associated with PCOS.

Table 546-3 CAUSES OF HIRSUTISM

PERIPHERAL

GONADAL

ADRENAL

EXOGENOUS

CONGENITAL ANOMALIES

Adapted from Bailey-Pridham DD, Sanfilippo JS: Hirsutism in the adolescent female, Pediatr Clin North Am 36:581–599, 1989.

Azziz R, Carmina E, Dewailly D, et alTask Force on the Phenotype of the Polycystic Ovary Syndrome of the Androgen Excess and PCOS Society. The Androgen Excess and PCOS Society criteria for the polycystic ovary syndrome: the complete task force report. Fertility and Sterility. 2009;91:456-488.

Balen A, Homberg R, Franks S. Defining polycystic ovary syndrome. BMJ. 2009;338:426-427.

Blank SK, Helm KD, McCartnery CR, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome in adolescence. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2008;1135:76-84.

Harwood K, Vuguin P, DiMartino-Nardi J. Current approaches to the diagnosis and treatment of polycystic ovarian syndrome in youth. Horm Res. 2007;68:209-217.

Hoeger K, Davidson K, Kochman L, et al. The impact of metformin, oral contraceptives, and lifestyle modification on polycystic ovary syndrome in obese adolescent women in two randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:4299-4306.

Nestler JE. Metformin for the treatment of the polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:47-54.

Norman RJ, Dewailly D, Legro RS, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome. Lancet. 2007;370:685-696.

O’Brien RF, Emans SJ. Polycystic ovary syndrome in adolescents. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2008;21:119-128.

Palomba S, Pasqualit R, Orio FJr, et al. Clomiphene citrate, metformin or both as first-step approach in treating anovulatory infertility in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): a systematic review of head-to-head randomized controlled studies and meta-analysis. Clin Endocrinol. 2009;70:11-321.

Sathyapalan T, Atkin SL. Investigating hirsutism. BMJ. 2009;338:1070-1072.

Sir-Petermann T, Codner E, Pérez V, et al. Metabolic and reproductive features before and during puberty in daughters of women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:1923-1930.

Soares GM, Vieira CS, Matrins WP, et al. Increased arterial stiffness in nonobese women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) without comorbidities: one more characteristic inherent to the syndrome? Clin Endocrinol. 2009;71:406-411.