Pneumothorax

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

• List the anatomic alterations of the lungs associated with a pneumothorax.

• Describe the causes of a pneumothorax.

• List the cardiopulmonary clinical manifestations associated with a pneumothorax.

• Describe the general management of a pneumothorax.

• Describe the clinical strategies and rationales of the SOAPs presented in the case study.

• Define key terms and complete self-assessment questions at the end of the chapter and on Evolve.

Anatomic Alterations of the Lungs

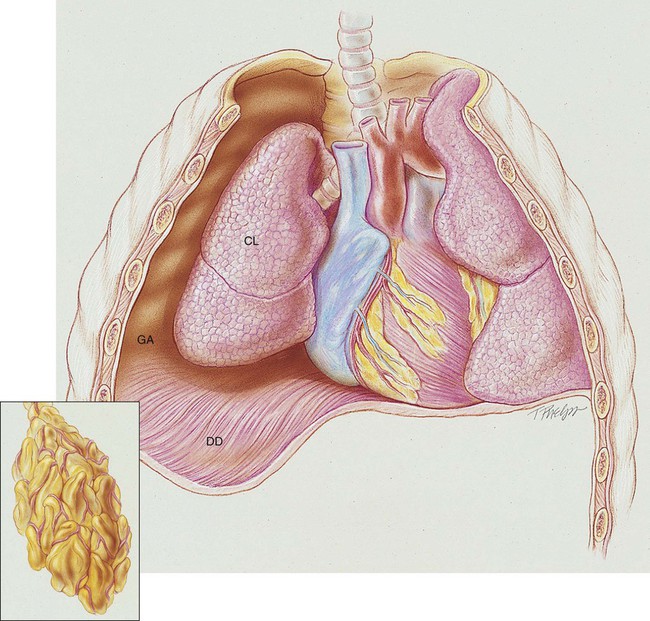

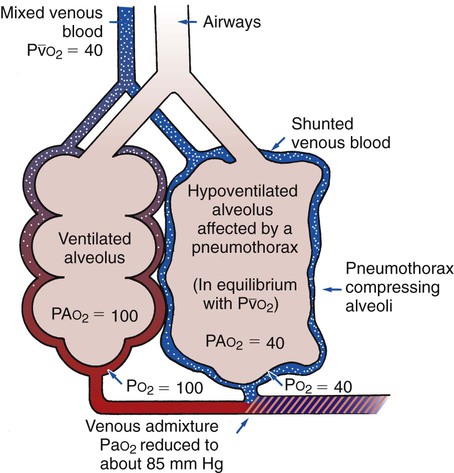

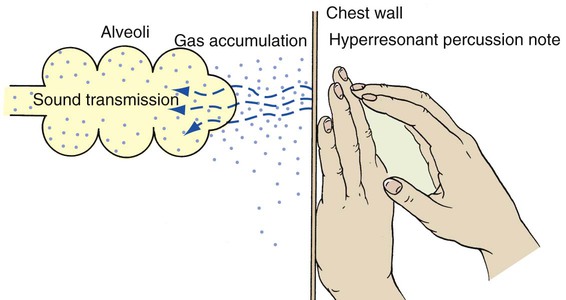

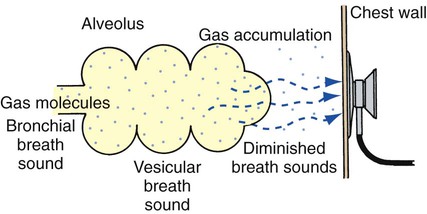

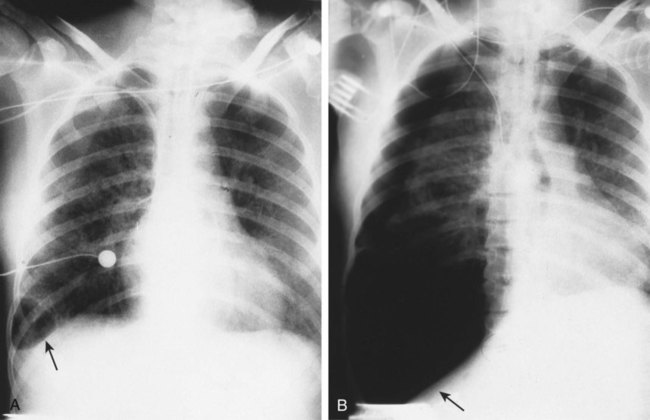

A pneumothorax exists when gas (sometimes called free air) accumulates in the pleural space (see Figure 22-1). When gas enters the pleural space, the visceral and parietal pleura separate. This enhances the natural tendency of the lungs to recoil, or collapse, and the natural tendency of the chest wall to move outward, or expand. As the lung collapses, the alveoli are compressed and atelectasis ensues. In severe cases, the great veins may be compressed and cause the venous return to the heart to diminish.

Etiology and Epidemiology

Gas can gain entrance to the pleural space in the following three ways:

1. From the lungs through a perforation of the visceral pleura

2. From the surrounding atmosphere through a perforation of the chest wall and parietal pleura or, rarely, through an esophageal fistula or a perforated abdominal viscus

3. From gas-forming microorganisms in an empyema in the pleural space (rare)

Traumatic Pneumothorax

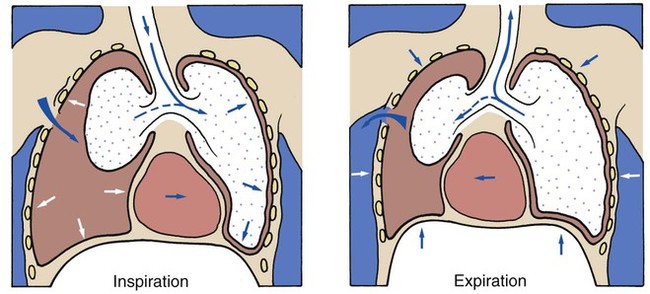

Penetrating wounds to the chest wall from a knife, a bullet, or an impaling object in an automobile or industrial accident are common causes of traumatic pneumothorax. When this type of trauma occurs, the pleural space is in direct contact with the atmosphere, and gas can move into and out of the pleural cavity. This condition is known as a sucking chest wound and is classified as an open pneumothorax (Figure 22-2).

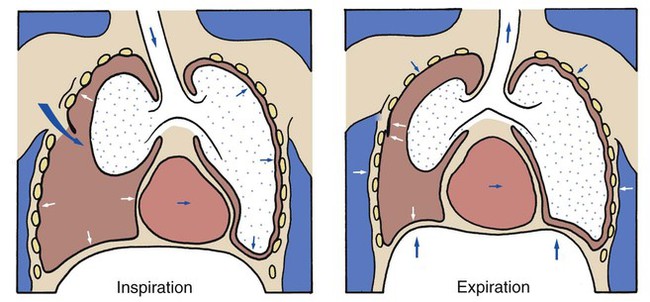

A piercing chest wound also may result in a closed (valvular) or tension pneumothorax through a one-way valvelike action of the ruptured parietal pleura. In this form of pneumothorax, gas enters the pleural space during inspiration but cannot leave during expiration because the parietal pleura (or, more infrequently, the chest wall itself) acts as a check valve. This condition may cause the intrapleural pressure to exceed the atmospheric pressure in the affected area. Technically this form of pneumothorax is classified as a tension pneumothorax (Figure 22-3). This form of pneumothorax is the most serious of all.

Spontaneous Pneumothorax

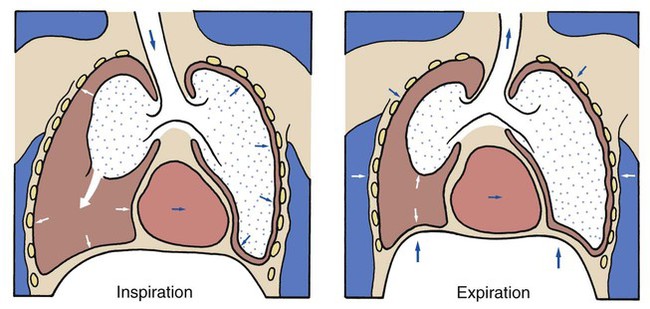

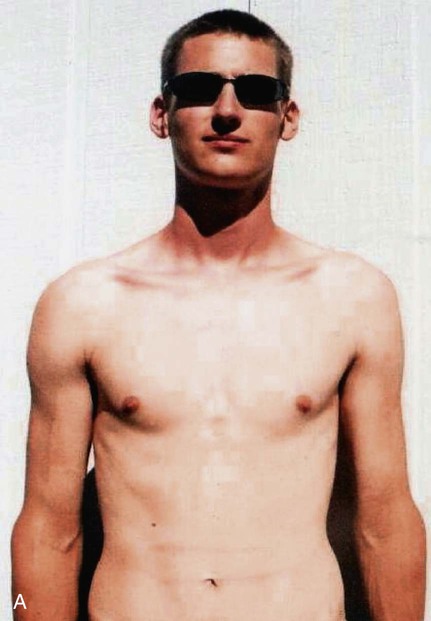

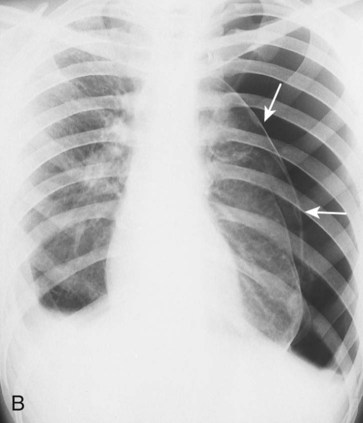

When a pneumothorax occurs suddenly and without any obvious underlying cause, it is referred to as a spontaneous pneumothorax. A spontaneous pneumothorax is secondary to certain underlying pathologic processes such as pneumonia, tuberculosis, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). A spontaneous pneumothorax is sometimes caused by the rupture of a small bleb or bulla on the surface of the lung. This type of pneumothorax often occurs in tall, thin persons aged 15 to 35 years. It may result from the high negative intrathoracic pressure and mechanical stresses that take place in the upper zone of the upright lung (Figure 22-4).

A spontaneous pneumothorax also may behave as a tension pneumothorax. Air from the lung parenchyma may enter the pleural space via a tear in the visceral pleura during inspiration but is unable to leave during expiration because the visceral tear functions as a check valve (see Figure 22-4). This condition may cause the intrapleural pressure to exceed the intraalveolar pressure. This form of pneumothorax is classified as both a closed pneumothorax and a tension pneumothorax.

CASE STUDY

Spontaneous Pneumothorax

Admitting History and Physical Examination

Respiratory Assessment and Plan

S Left chest pain worsened by cough; shortness of breath

O Normal vital signs. Left chest hyperresonant. Trachea shifted to the right. Breath sounds on left “distant.”

A Probable left tension pneumothorax (history and objective indicators)

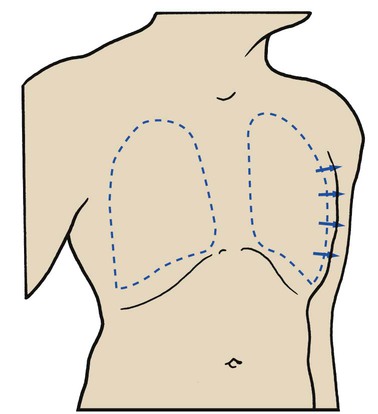

P Notify physician (who is in the next room). Request stat CXR and ABG. Oxygen Therapy Protocol (partial rebreathing mask with Fio2 between 0.6 to 0.8). Oxygen therapy via partial rebreathing mask (Fio2 0.6 to 0.8). Obtain supplies for tube thoracostomy and place at patient’s bedside.

Respiratory Assessment and Plan

S “This oxygen mask helps a little.”

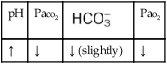

O Persistent symptoms and physical findings as in SOAP-1 above. CXR: 50% left tension pneumothorax. Mediastinum shifted to right. ABGs: pH 7.53, Paco2 29,  21, and Pao2 56 (on partial rebreathing mask).

21, and Pao2 56 (on partial rebreathing mask).

P Inform physician of previous and current assessment. Up-regulate Oxygen Therapy Protocol (Increase Fio2 to 0.8 to 1.0 via a nonrebreathing mask). Stay at patient’s bedside until physician arrives. Assist in placement of chest tube.

Discussion

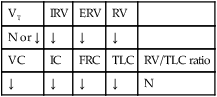

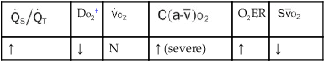

This case nicely demonstrates the signs and symptoms of Atelectasis and intrapulmonary shunting (see Figure 9-8). The physician and respiratory therapist could not hear crackles, however, presumably because the atelectatic segments were separated (distant) from the chest wall and the examiner’s stethoscope.

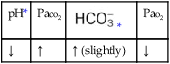

ratio decreases. This leads to intrapulmonary shunting and venous admixture (

ratio decreases. This leads to intrapulmonary shunting and venous admixture (

values will be lower than expected for a particular Pa

values will be lower than expected for a particular Pa

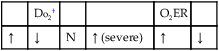

, Arterial-venous oxygen difference; DO2, total oxygen delivery; O2ER, oxygen extraction ratio;

, Arterial-venous oxygen difference; DO2, total oxygen delivery; O2ER, oxygen extraction ratio;  , pulmonary shunt fraction;

, pulmonary shunt fraction;  , mixed venous oxygen saturation;

, mixed venous oxygen saturation;  , oxygen consumption.

, oxygen consumption.

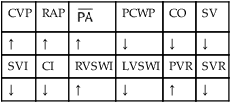

, mean pulmonary artery pressure; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; RAP, right atrial pressure; RVSWI, right ventricular stroke work index; SV, stroke volume; SVI, stroke volume index; SVR, systemic vascular resistance.

, mean pulmonary artery pressure; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; RAP, right atrial pressure; RVSWI, right ventricular stroke work index; SV, stroke volume; SVI, stroke volume index; SVR, systemic vascular resistance.

21, and Pa

21, and Pa