51 Pneumothorax

• Primary pneumothoraces (spontaneous or traumatic) occur in patients without clinically apparent lung disease.

• Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is the most common cause of secondary pneumothorax.

• Physical examination may miss a pneumothorax occupying up to 27% of lung volume.

• Standard posteroanterior and lateral chest radiographs are the only routine examination needed because expiratory films add little to diagnostic accuracy.

• Ultrasound’s lung point sign has an overall sensitivity of 66% and a specificity of 100%.

• Treatment of pneumothorax is based on its cause, size and stability, symptoms, and the presence or absence of underlying lung disease. Treatment options include observation, catheter aspiration, and tube thoracostomy.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Pneumothorax

The ability of auscultation to detect hemothorax, pneumothorax, or hemopneumothorax associated with penetrating trauma had a sensitivity of 58%, a specificity of 98%, and a positive predictive value of 98% in one study.1 Auscultation can miss up to 600 mL of hemothorax, a pneumothorax occupying up to 28% of lung volume, and a combined hemopneumothorax of up to 800 mL and 28%.1 Physical examination alone is not sensitive enough to exclude the diagnosis of pneumothorax.

Diagnostic Testing and Medical Decision Making (Table 51.1)

Radiography

The primary evaluation tool is the standard posteroanterior chest radiograph to look for loss of lung markings in the periphery and a pleural line that runs parallel to the chest wall but does not extend outside the chest cavity. A lateral radiograph contributes to the diagnosis in 14% of cases.2 There is no evidence that an expiratory radiograph adds any value even with small apical pneumothoraces.3 The sensitivity for flat anteroposterior chest radiography, versus computed tomography (CT) as the “gold standard,” has been found to be 75.5% (95% confidence interval [CI], 61.7% to 86.2%), and the specificity is 100% (95% CI, 97.1% to 100%).4

| Pulmonary embolism | Perform a risk stratification based on the Wells or Charlotte criteria. If the result of stratification is not low probability or the D-dimer test result is positive, proceed to computed tomography–pulmonary angiography. A chest radiograph may show infarcted lung. |

| Pleurisy | Look for an underlying disease process (connective tissue, pneumonia). Pleura-based diseases (pneumonia, tumor, effusion) often have radiographic findings. |

| Pneumonia | Chest radiography will be helpful. Clinical examination and the history may suggest pneumonia because of cough (uncommon with pneumothorax), upper respiratory symptoms, fever, or immunosuppression. |

| Pericarditis | Look for an underlying disease process. Check the electrocardiogram (ECG) for classic but not common PR-segment depression and/or widespread ST-segment elevation. Does position affect the pain (less with leaning forward, more with lying back)? Consider ultrasonography to diagnose effusion. |

| Myocardial infarction | Assess for appropriate risk factors. Evaluate with an ECG and cardiac marker measurements if suspicious. ECG findings associated with a pneumothorax include axis deviation, decreased voltage, and T-wave inversion. |

| Aortic dissection | Interscapular back pain with a tearing sensation is typical. Check the chest radiograph for a widened mediastinum, apical capping, left-sided pleural effusion, blurring of the aortic knob, or displacement of the trachea or esophagus to the anatomic right. Consider checking bilateral arm pressures. Look for a neurologic deficit or end-organ ischemia. |

| Musculoskeletal pain | Is the pain reproducible with palpation and use of the muscle group? Does the patient have a history consistent with muscle injury? Are the findings on chest radiography and ECG normal? |

| Pneumomediastinum | Is subcutaneous emphysema present on physical examination? Is mediastinal, pericardiac, or prevertebral air found on the chest radiograph? Does it typically occur during a Valsalva maneuver or exertion? |

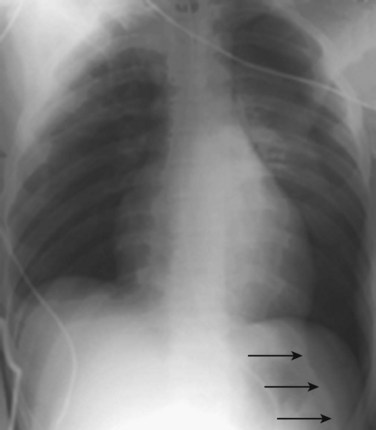

Shift of the mediastinum away from a pneumothorax on a chest radiograph can be a normal phenomenon that occurs without tension physiology. In critically ill patients in whom a radiograph can be taken only in the supine position, the emergency physician (EP) should look for the presence of a deep sulcus sign—a deep lateral costophrenic angle on the ipsilateral side (Fig. 51.1). Diaphragmatic depression or ipsilateral transradiancy (fewer lung markings, clearer image) may also be seen.5

Ultrasonography

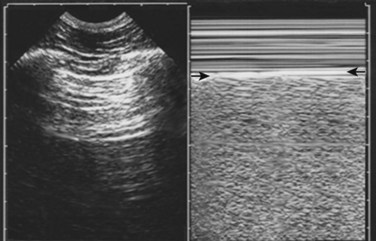

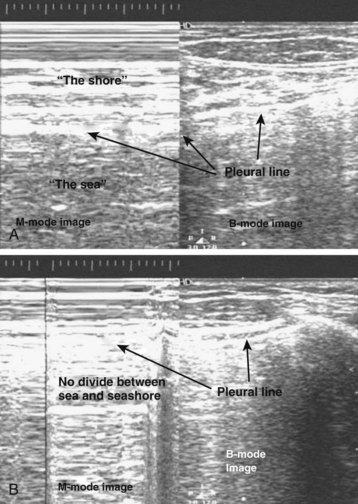

Normal lung shows a shimmering echogenic stripe of both the parietal and visceral pleura on ultrasonography. A sliding sign at the pleural stripe can be seen with movement of the visceral pleura in relation to the parietal pleura. The “seashore analogy” refers to movement of the lung (ocean) against the stationary chest wall (shore). A comet tail reverberation can be seen distal to the pleura when no pneumothorax is present. The sliding sign of the pleural stripe and the comet tail reverberation are lost with a pneumothorax because of intrapleural air6 (Fig. 51.2). Doppler mode may be of some help in detecting this movement. Multiple other reasons can account for loss of the sliding, including atelectasis, mainstem intubation, acute respiratory distress syndrome, pleural adhesions, and pulmonary contusion, thus limiting specificity for pneumothorax in some cases.

Fig. 51.2 Ultrasonograms of abnormal (A) and normal (B) pleura with M-mode and B-mode imaging.

(Courtesy Christopher L. Moore, MD, Yale University School of Medicine.)

Deep to this pleural line, vertical artifacts called B lines may be seen. They originate at the pleural line, align vertically, continue the entire depth of the screen without any fading, and move with breathing. The finding of B lines rules out the presence of a pneumothorax, but the absence of B lines does not signify the presence of a pneumothorax.7

The lung point sign has a specificity approaching 100% for pneumothorax and is determined by the absence of lung sliding and B lines. The probe is moved gradually toward the lateral lower aspect of the chest.8 The goal is to identify lung sliding and B lines suggesting the “point” at which the lung is adherent to the pleura again (Fig. 51.3). A large pneumothorax may not display this point, thus diminishing the sensitivity of the lung point sign.

The sensitivity of ultrasound detection of pneumothorax has been found to be 98.1% (95% CI, 89.9% to 99.9%) and the specificity was 99.2% (95% CI, 95.6% to 99.9%), which makes it more sensitive than a flat-plate anteroposterior radiograph.4 The use of ultrasonography as part of the extended focused assessment with sonography for trauma (eFAST) examination has been suggested in unstable patients with suspected pneumothorax.

Computed Tomography

CT is more accurate than radiography for the detection of pneumothoraces; it detects between 25% and 40% of pneumothoraces after lung biopsy that were not visualized on postprocedure chest radiographs.9 Up to 50% of traumatic pneumothoraces may be occult. CT can detect other problems, such as pulmonary blebs, vascular abnormalities, contusions, infiltrates, and tumors. CT is recommended in uncertain or complex cases such as symptomatic high-risk patients with suspected occult pneumothorax, those who have underlying lung disease, patients undergoing positive pressure ventilation, or those just completing lung biopsy.

Determining the Size of the Pneumothorax

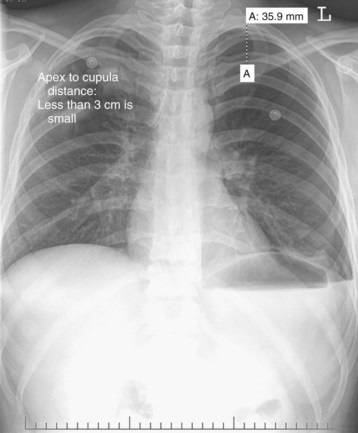

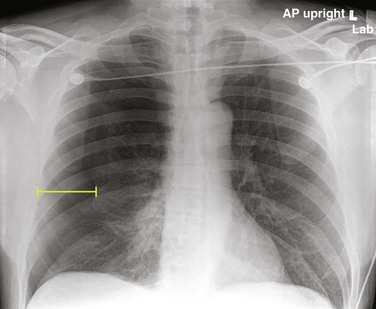

U.S. guidelines suggest measurement from the apex of the lung to the cupula of the thoracic cavity on an upright posteroanterior radiograph (Fig. 51.4). Less than 3 cm is considered small. British guidelines (2010) suggest the interpleural distance at the level of the hilum (Fig. 51.5). A 2-cm distance correlates with an approximate 50% pneumothorax by volume.10

CT-directed size classification allows grading of occult pneumothoraces. Minuscule refers to air collections less than 1 cm thick that appear on fewer than five contiguous 10-mm slices. Anterior pneumothoraces are air collections more than 1 cm thick that appear on five or more contiguous 10-mm slices and do not extend to the midcoronal line (Fig. 51.6). Anterolateral pneumothoraces extend to the midcoronal line or beyond.

Treatment

![]() Priority Actions

Priority Actions

2. Determine whether tension pneumothorax physiology exists. If present, proceed to tube thoracostomy without delay for imaging.

3. Close an open pneumothorax with a three-sided dressing.

4. Obtain posteroanterior and lateral chest radiographs.

5. Determine the size of the pneumothorax.

6. Assess the patient for underlying lung disease, adhesions, and other complications.

Hospital Management

Oxygen should be administered to all patients with a pneumothorax because it helps in resorption of the pneumothorax and increases oxygenation of the available alveoli in the noncollapsed lung. The untreated resorption rate is 1% to 2% per day, and the rate increases fourfold with the administration of 100% oxygen.11

A stable patient with pneumothorax has been described as one who has a respiratory rate of less than 24 breaths/min, a heart rate between 60 and 120 beats/min, normal blood pressure, oxygen saturation greater than 90% when breathing room air, and the ability to speak in full sentences between breaths.12

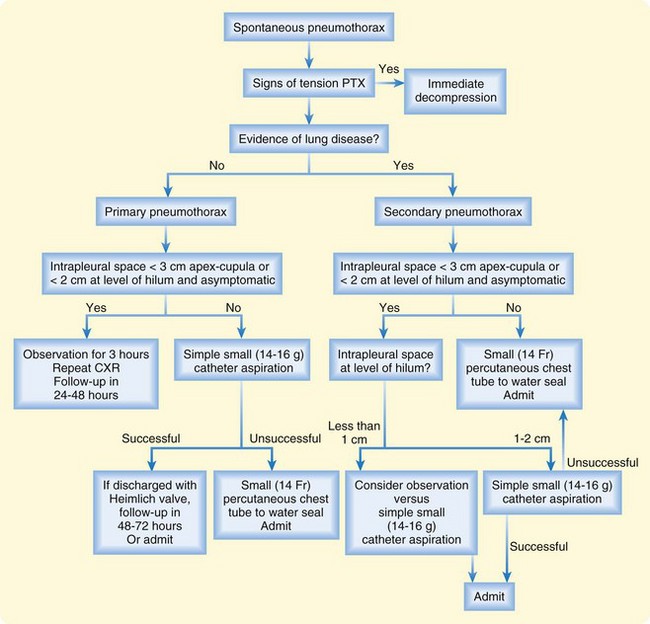

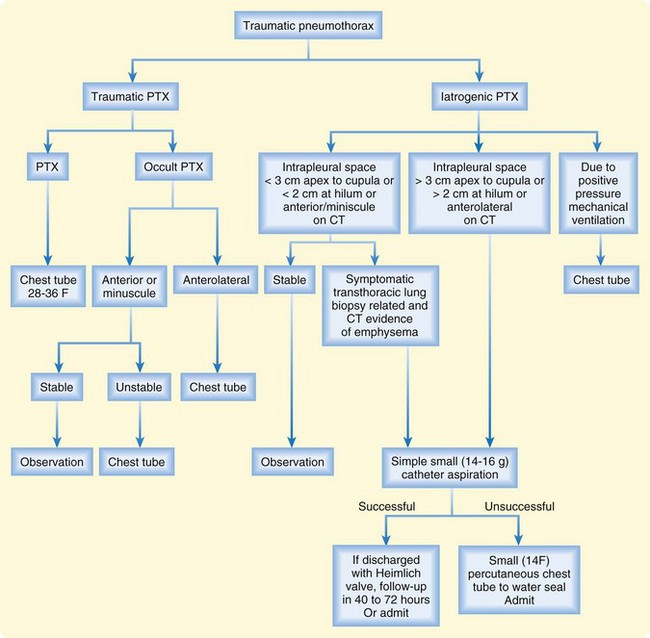

Figures 51.7 and 51.8 present algorithms to assess the need for intervention in patients with primary spontaneous pneumothorax or traumatic pneumothorax, respectively. Patients with bilateral pneumothoraces are treated by aspiration or chest tube placement.

Heimlich Valve

A Heimlich valve is a one-way valve that can be attached to the end of a chest tube. Suction has not been proved to aid in reexpansion or the outcome of a pneumothorax, and it is not recommended. Instead, a water seal or Heimlich valve is used.13 A Heimlich valve allows the patient to ambulate unrestricted. It should not be used in patients with underlying lung disease or other medical problems that prevent them from tolerating a recurrence of the pneumothorax. Complications of this method include obstruction of the valve with fluid and disconnection.

Follow-Up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

Disposition

The disposition of patients with pneumothorax is detailed in the algorithms in Figures 51.7 and 51.8. A patient with a primary spontaneous pneumothorax who has been treated by observation or catheter aspiration can be discharged if the pneumothorax does not increase over a period of 3 to 6 hours and the symptoms do not worsen. For a patient discharged with a primary spontaneous pneumothorax without intervention, follow-up should occur in the next 24 to 48 hours to document stability or resolution of the pneumothorax.

![]() Documentation

Documentation

Document the presence of underlying lung disease to establish the primary versus secondary status of the pneumothorax.

In the case of primary pneumothorax, document whether it was traumatic.

Document the estimated size of the pneumothorax and method of intervention.

If the patient is being discharged, document follow-up and discussion of reasons to return.

![]() Patient Teaching Tips

Patient Teaching Tips

The patient must stop smoking.

There is no limitation on physical activity.

Patients should return to the emergency department immediately for recurrence of symptoms.

Safety regulations state that a patient cannot fly for 3 weeks after treatment, and diving is also contraindicated.

A patient with a primary spontaneous pneumothorax has a 30% recurrence rate within 2 years after air evacuation only; a patient who has had two pneumothoraces has an 80% chance of recurrence.

Patients sent home after observation should undergo follow-up within 24 to 48 hours to document stability or resolution of the pneumothorax.

In patients with a secondary (associated with underlying lung disease) spontaneous pneumothorax, the treatment algorithm is altered by the underlying lung disease. Clinically stable patients, regardless of the duration of symptoms, should not be monitored in the ED or treated with catheter aspiration and discharged. They should all be admitted to the hospital for observation, simple aspiration, or tube thoracostomy.13

Complications

Complications of pneumothorax include those related to hypoxia, hypercapnia, and hypotension. Reexpansion lung injury is rare but most commonly occurs after reexpansion of a large pneumothorax. Risk factors appear to include collapse of the lung for longer than 72 hours, a large pneumothorax, rapid reexpansion, and use of negative pleural pressure suction greater than 20 cm H2O.14

Haynes D, Baumann MH. Management of pneumothorax. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;31:769–780.

MacDuff A, Arnold A, Harvey J. Management of spontaneous pneumothorax: British Thoracic Society Pleural Disease Guideline 2010. Thorax. 2010;65:ii18–ii31.

Volpicelli G. Sonographic diagnosis of pneumothorax. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37:224–232.

1 Chen SC, Markmann JF, Kauder DR, et al. Hemopneumothorax missed by auscultation in penetrating chest injury. J Trauma. 1997;42:86–89.

2 Glazer HS, Anderson DJ, Wilson BS, et al. Pneumothorax: appearance on lateral chest radiographs. Radiology. 1989;173:707–711.

3 Schramel FM, Golding RP, Haakman CD, et al. Expiratory chest radiographs do not improve visibility of small apical pneumothoraces by enhanced contrast. Eur Respir J. 1996;9:406–409.

4 Blaivas M, Lyon M, Duggal S. A prospective comparison of supine chest radiography and bedside ultrasound for the diagnosis of traumatic pneumothorax. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:844–849.

5 Tocino IM, Miller MH, Fairfax WR. Distribution of pneumothorax in the supine and semirecumbent critically ill adult. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1985;144:901–905.

6 Goodman TR, Traill ZC, Phillips AJ, et al. Ultrasound detection of pneumothorax. Clin Radiol. 1999;54:736–739.

7 Volpicelli G. Sonographic diagnosis of pneumothorax. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37:224–232.

8 Lichtenstein D, Meziere G, Biderman P, et al. The “lung point”: an ultrasound sign specific to pneumothorax. Intensive Care Med. 2000;26:1434–1440.

9 Bungay HK, Berger J, Traill ZC, et al. Pneumothorax post CT-guided lung biopsy: a comparison between detection on chest radiograph and CT. Br J Radiol. 1999;72:1160–1163.

10 MacDuff A, Arnold A, Harvey J. Management of spontaneous pneumothorax: British Thoracic Society Pleural Disease Guideline 2010. Thorax. 2010;65:ii18–ii31.

11 Northfield TC. Oxygen therapy for spontaneous pneumothorax. BMJ. 1971;4:86–88.

12 Baumann MH, Strange C, Heffner JE, et al. Management of spontaneous pneumothorax: an American College of Chest Physicians Delphi Consensus Statement. Chest. 2001;119:590–602.

13 Haynes D, Baumann MH. Management of pneumothorax. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;31:769–780.

14 Henry M, Arnold T, Harvey J, et al. BTS guidelines for the management of spontaneous pneumothorax. Thorax. 2003;58(Suppl II):ii39–ii52.