Pneumonia

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

• List the anatomic alterations of the lungs associated with pneumonia.

• Describe the causes and classifications of pneumonia.

• List the cardiopulmonary clinical manifestations associated with pneumonia.

• Describe the general management of pneumonia.

• Describe the clinical strategies and rationales of the SOAPs presented in the case study.

• Define key terms and complete self-assessment questions at the end of the chapter and on Evolve.

Anatomic Alterations of the Lungs

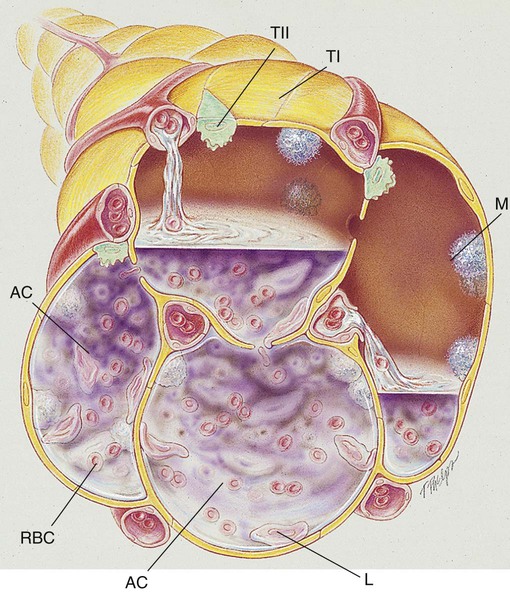

Pneumonia, or pneumonitis with consolidation, is the result of an inflammatory process that primarily affects the gas exchange area of the lung. In response to the inflammation, fluid (serum) and some red blood cells (RBCs) from adjacent pulmonary capillaries pour into the alveoli. This process of fluid transfer is called effusion. Polymorphonuclear leukocytes move into the infected area to engulf and kill invading bacteria on the alveolar walls. This process has been termed surface phagocytosis. Increased numbers of macrophages also appear in the infected area to remove cellular and bacterial debris. If the infection is overwhelming, the alveoli become filled with fluid, RBCs, polymorphonuclear leukocytes, and macrophages. When this occurs, the lungs are said to be consolidated (Figure 15-1). Atelectasis is often associated with patients who have aspiration pneumonia.

The major pathologic or structural changes associated with pneumonia are as follows:

Etiology and Epidemidogy

Pneumonia is an insidious disease because its symptoms vary greatly depending on the patient’s specific underlying condition and the type of organism causing the pneumonia. Often what is initially thought to be a cold or the flu can in fact be a much more serious pulmonary infection. The early recognition and treatment of pneumonia provide the best chance for a full recovery. There are over 30 causes of pneumonia. The major ones are listed in Box 15-1 and are discussed in the following paragraphs.

Bacterial Causes

Gram-Positive Organisms

Streptococcal pneumonia

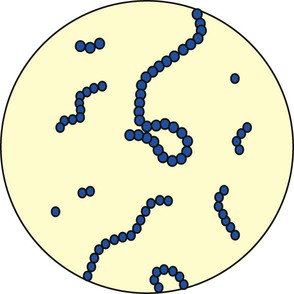

Streptococcus pneumoniae accounts for more than 80% of all the bacterial pneumonias. The organism is a gram-positive, nonmotile coccus that is found singly, in pairs (called diplococci), and in short chains (Figure 15-2). The cocci are enclosed in a smooth, thick polysaccharide capsule that is essential for virulence. There are more than 80 different types of S. pneumoniae. Serotype 3 organisms are the most virulent. Streptococci are generally transmitted by aerosol from a cough or sneeze of an infected individual. Most strains of S. pneumoniae are sensitive to penicillin and its derivatives. S. pneumoniae also is commonly cultured from the sputum of patients having an acute exacerbation of chronic bronchitis.

Staphylococcal pneumonia

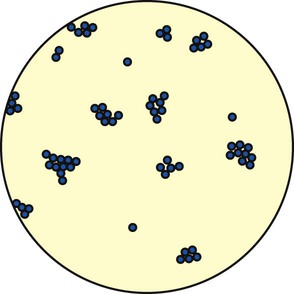

There are two major groups of Staphylococcus: (1) Staphylococcus aureus, which is responsible for most “staph” infections in humans, and (2) Staphylococcus albus and Staphylococcus epidermidis, which are part of the normal skin flora. The staphylococci are gram-positive cocci found singly, in pairs (called diplococci), and in irregular clusters (Figure 15-3). Staphylococcal pneumonia often follows a predisposing virus infection and is seen most often in children and immunosuppressed adults. S. aureus is commonly transmitted by aerosol from a cough or sneeze of an infected individual and indirectly via contact with contaminated floors, bedding, clothes, and the like. Staphylococci are a common cause of hospital-acquired pneumonia and are becoming increasingly antibiotic resistant—thus the term multiple drug–resistant S. aureus (MDRSA) organisms (some centers shorten this acronym to MRSA).

Gram-Negative Organisms

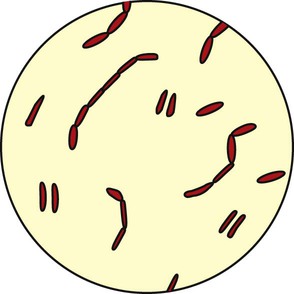

The major gram-negative organisms responsible for pneumonia are rod-shaped microorganisms called bacilli (Figure 15-4). The bacilli described in the following sections are frequently seen in the clinical setting.

Viral Causes

Respiratory Syncytial Virus

The respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) (see Chapter 36) is a member of the paramyxovirus group. Parainfluenza, mumps, and rubella viruses also belong to this group. RSV is most often seen in children less than 12 months of age and in older adults with underlying heart or pulmonary disease. Almost all children will be infected with RSV by their second birthday. The infection is rarely fatal in infants. RSV often goes unrecognized but may play an important role as a forerunner to bacterial infections. Early attempts to develop an RSV vaccine have been unsuccessful. The virus is transmitted by aerosol and by direct contact with infected individuals. RSV infections are most commonly seen in patients during the late fall, winter, or early spring months. Many times the virus is misdiagnosed in older children, who are given antibiotics that do not work.

Other Causes

Rickettsiae

Aspiration Pneumonitis

1. Toxic injury to the lung (such as that caused by gastric acid)

Normal swallowing mechanics has four phases, as follows:

• Elevation and retraction of the velopharyngeal port (velum closure)

• Pharyngeal muscle contraction

• Elevation and forward excursion of the larynx (epiglottic closure)

• Closure of the laryngeal vestibule, false vocal folds, and true vocal folds (laryngeal closure)

Six cranial nerves carry motor signals generated by cerebral and brain stem swallowing centers:

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (see Chapter 17) is an infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. M. tuberculosis is a slender, rod-shaped aerobic organism. Predisposing factors of tuberculosis include homelessness, drug abuse, and AIDS. The initial response of the lung is an inflammatory reaction that is similar to any acute pneumonia (see Chapter 17).

Fungal Infections

Because most fungi are aerobes, the lung is a prime site for fungal infections (see Chapter 18). Primary fungal pathogens include Histoplasma capsulatum, Coccidioides immitis, and Blastomyces dermatitidis. In addition, the opportunistic yeast pathogens Candida albicans, Cryptococcus neoformans, and Aspergillus also may cause pneumonia in certain patients. For example, C. albicans, which occurs as normal flora in the oral cavity, genitalia, and large intestine, is rarely seen in the tracheobronchial tree or lung parenchyma. In patients with AIDS, however, C. albicans commonly causes an infection of the mouth, pharynx, esophagus, vagina, skin, and lungs. A C. albicans infection of the mouth is called thrush; it is characterized by a white, adherent, patchy infection of the membranes of the mouth, gums, cheeks, and throat.

C. neoformans proliferates in pigeon droppings, which have a high nitrogen content, and readily scatters into the air and dust. Today, the highest rate of cryptococcosis occurs among patients with AIDS and persons undergoing steroid therapy. The molds of the genus Aspergillus may be the most pervasive of all fungi—especially Aspergillus fumigatus. Aspergillus is found in soil, vegetation, leaf detritus, food, and compost heaps. Persons who breathe the air of granaries, barns, and silos are at the greatest risk. Aspergillus infection usually occurs in the lungs. Aspergillus is almost always an opportunistic infection and lately has posed a serious threat to patients with AIDS. When fungal organisms are inhaled, the initial response of the lung is an inflammatory reaction similar to that produced by any acute pneumonia (see Chapter 18).

General Management of Pneumonia

Medications and Procedures Commonly Prescribed by the Physician

Antibiotics

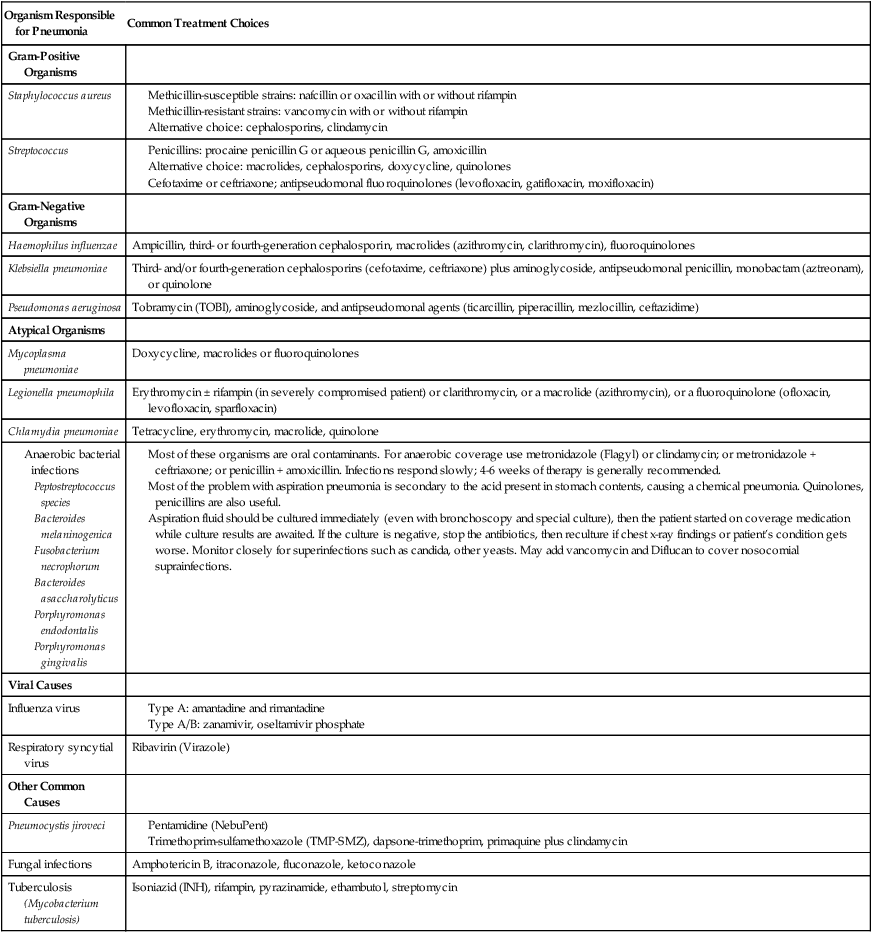

Antibiotics are commonly administered to combat the infective agents that cause bacterial pneumonia. Table 15-1 provides an overview of the commonly encountered organisms responsible for pneumonia and the therapeutic agents currently used to treat them.

TABLE 15-1

| Organism Responsible for Pneumonia | Common Treatment Choices |

| Gram-Positive Organisms | |

| Staphylococcus aureus |

Most of these organisms are oral contaminants. For anaerobic coverage use metronidazole (Flagyl) or clindamycin; or metronidazole + ceftriaxone; or penicillin + amoxicillin. Infections respond slowly; 4-6 weeks of therapy is generally recommended.

Most of the problem with aspiration pneumonia is secondary to the acid present in stomach contents, causing a chemical pneumonia. Quinolones, penicillins are also useful.

Aspiration fluid should be cultured immediately (even with bronchoscopy and special culture), then the patient started on coverage medication while culture results are awaited. If the culture is negative, stop the antibiotics, then reculture if chest x-ray findings or patient’s condition gets worse. Monitor closely for superinfections such as candida, other yeasts. May add vancomycin and Diflucan to cover nosocomial suprainfections.

Respiratory Care Treatment Protocols

Oxygen Therapy Protocol

Oxygen therapy is used to treat hypoxemia, decrease the work of breathing, and decrease myocardial work. Because of the hypoxemia associated with pneumonia, supplemental oxygen may be required. The hypoxemia that develops in pneumonia is most commonly caused by alveolar consolidation and capillary shunting associated with the disorder. Hypoxemia caused by capillary shunting is at least partially refractory to oxygen therapy (see Oxygen Therapy Protocol, Protocol 9-1).

Bronchopulmonary Hygiene Therapy Protocol

Because of the airway secretions associated with the resolution stage of pneumonia, a number of bronchopulmonary hygiene treatment modalities may be used to enhance the mobilization of bronchial secretions. In addition, because of food particles in the aspirate, the bronchopulmonary hygiene protocol is useful in the treatment of aspiration pneumonia (see Bronchopulmonary Hygiene Therapy Protocol, Protocol 9-2).

Respiratory Assessment and Plan

S “I feel miserable.” Mild dyspnea.

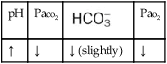

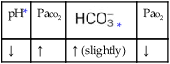

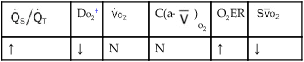

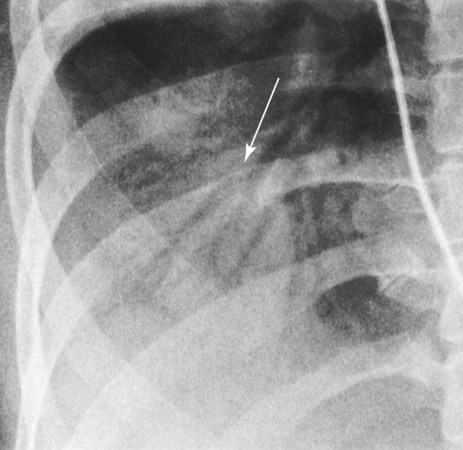

O Alert, cooperative, acutely ill. Mild nonproductive cough. Vital signs: T 39.9° C, BP 150/88, P 116, RR 28. Dull to percussion over RLL, along with crackles and bronchial breath sounds. CXR: Pneumonic consolidation RLL. ABG on room air: pH 7.53, Paco2 27,  21, and Pao2 62.

21, and Pao2 62.

P Oxygen Therapy Protocol: Monitor Spo2. (Titrate O2 per NC as needed to keep Spo2 >90%.)

Respiratory Assessment and Plan

S Increased dyspnea. Symptoms of belching and substernal chest pain.

O Anxious appearance. BP 120/82, HR 140, RR 20, T 40° C. Cyanotic. Strong productive cough (sputum foul-smelling, yellow-green). Bronchial breath sounds, rhonchi, persistent crackles in right middle anterior chest and both bases. CXR: RML and LLL infiltrate and consolidation. ABG (on 2 L/min): pH 7.50, Paco2 29,  20, Pao2 36, and Sao2 69%.

20, Pao2 36, and Sao2 69%.

• Aspiration complicating community-acquired pneumonia, involving RML and LLL (history, CXR)

• Alveolar consolidation (CXR)

• Excessive airway secretions (thick, yellow-green sputum)

• Good ability to mobilize secretions (strong cough)

• Acute alveolar hyperventilation with severe hypoxemia (ABG)

P Oxygen Therapy Protocol: Increase Fio2 to 0.60 via HAFOE mask. Bronchopulmonary Hygiene Protocol: DB&C instruction, prn oropharyngeal suctioning. Trial P&D to lower lobes and RML q shift as tolerated). Aerosolized Medication Protocol: 2.0 mL 10% acetylcysteine with 0.5 mL albuterol q4h. ABG in 1 hour.

Discussion

A history of cold exposure in conjunction with the use of alcoholic beverages before the onset of pneumonia is not uncommon. The first part of this case begins with a classic presentation for community-acquired pneumonia with alveolar consolidation (see Alveolar Consolidation, Figure 9-9). For example, the fever and tachycardia represent a normal functioning immune response, and the tachycardia and tachypnea reflect the body’s response to shunt-induced hypoxemia. The auscultation of crackles and bronchial breath sounds also reflects the patient’s pulmonary consolidation. An attempt at improving his oxygenation, though not successful, was certainly in order. It was hoped that by providing an oxygen-enriched gas to both normal and partially consolidated alveoli, the effects of pulmonary shunting would be at least partially offset.

The second SOAP presents the complication of the patient’s community-acquired pneumonia with aspiration pneumonitis. Alcoholics frequently have gastritis or esophagitis, and the patient’s eructation (belching) and pyrosis (heartburn) were clues to the development of that complication. At this time there were new clinical manifestations associated with Excessive Bronchial Secretions (see Figure 9-12). For example, the patient demonstrated a cough, sputum, rhonchi, and crackles. The Bronchopulmonary Hygiene Therapy Protocol (e.g., mucolytic with a bronchodilator, DB&C, suctioning, and P&D) was appropriate. A trial of Lung Expansion Therapy (see Protocol 9-3) was not given in this case. However, Atelectasis (see Figure 9-8) often complicates aspiration pneumonia, and such a trial would not have been inappropriate.

In cases of pneumonia, the respiratory care practitioner is often tempted to do too much. Typically, volume expansion therapy, bronchodilator aerosol therapy, and bland aerosol therapy have all been ordered for affected patients, even in the acute, consolidative stage of their pneumonia. Often, however, all that is needed is the appropriate selection of antibiotics, rest, fluids, and supplementary oxygen. When the pneumonia “breaks up” (resolution stage) or is complicated by aspiration (as in this case), Excessive Bronchial Secretions (Figure 9-12) and even Bronchospasm (Figure 9-11) may appear. When this happens, use of other protocol modalities is necessary.

values will be lower than expected for a particular Pa

values will be lower than expected for a particular Pa

)

)

)O2, Arterial-venous oxygen difference; DO2, total oxygen delivery; O2ER, oxygen extraction ratio;

)O2, Arterial-venous oxygen difference; DO2, total oxygen delivery; O2ER, oxygen extraction ratio;  , pulmonary shunt fraction;

, pulmonary shunt fraction;  , mixed venous oxygen saturation;

, mixed venous oxygen saturation;  , oxygen consumption.

, oxygen consumption.

21, and Pa

21, and Pa 20, Pa

20, Pa