52 Pleural Effusion

• Pleural effusion is the manifestation of an underlying disease process.

• The most common cause of pleural effusion in developed countries is congestive heart failure.

• Pulmonary embolism should be considered in patients with pulmonary effusions of uncertain etiology.

• Therapeutic thoracentesis is indicated in the emergency department for relief of acute respiratory or cardiovascular distress.

• Diagnostic thoracentesis should be performed in the emergency department to diagnose immediately life-threatening conditions in toxic-appearing patients.

Epidemiology

Because pleural effusions are harbingers of underlying disease, their precise incidence is difficult to determine. The incidence in the United States is estimated to be at least 1.5 million cases annually.1 In industrialized countries worldwide, the incidence approaches 320 cases per 100,000 people—with heart failure, bacterial pneumonia, cirrhosis, malignancy, and pulmonary embolism representing the most common causes. The morbidity and mortality associated with pleural effusion are directly related to cause, stage of disease at the time of diagnosis, and biochemical findings in the pleural fluid. Because pleural effusions are manifestations of underlying diseases, age, sex, race, and socioeconomic status reflect the variation in incidence of the causative disease state or disorder.

Pathophysiology

The presence of fluid in the normally negative pressure environment of the pleural space has a number of consequences for respiratory physiology. Pleural effusions produce a restrictive ventilatory defect and also decrease total lung capacity, functional residual capacity, and forced vital capacity. They may cause ventilation-perfusion mismatches and, when large enough, compromise cardiac output.2

The classic work of Light et al.3 in 1972 demonstrated that 99% of pleural effusions could be classified into these two general categories, transudative and exudative (Box 52.1). A basic difference is that transudates generally reflect a systemic process whereas exudates usually signify underlying local pleuropulmonary disease.3

Box 52.1 Light Criteria for Classification of Pleural Effusions

In 1972, Light et al.3 developed the currently accepted benchmark for classifying pleural fluid, as follows:

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

In many cases, pleural effusions are asymptomatic when discovered. Physical findings of pleural effusions are unlikely to be manifested until an effusion exceeds 300 mL. Dyspnea, the most common symptom associated with pleural effusion, is related more to distortion of the diaphragm and chest wall during respiration than to hypoxemia. Less commonly, symptoms of pleural effusions consist of a mild, nonproductive cough and chest pain. Pleuritic chest pain indicates inflammation of the parietal pleura because the visceral pleura is not innervated. In many patients, drainage of pleural fluid alleviates the symptoms despite limited improvement in gas exchange. Findings on lung examination such as decreased breath sounds, dullness to percussion, pleural friction rub, egophony, and reduced tactile fremitus have all been described.1,2 Auscultation alone can miss up to 600 mL of fluid in the lung.4–6

The emergency physician should assess for the cause of the effusion. If a patient complains of fever, weight loss, and a progressively worsening cough with associated dyspnea, an oncologic or infectious cause is likely. Constant chest wall pain may reflect chest wall invasion by bronchogenic carcinoma or malignant mesothelioma. Pleuritic chest pain suggests either pulmonary embolism or an inflammatory pleural process. An effusion can mimic the classic symptoms of acute coronary syndrome, such as chest pain, dyspnea, and shoulder pain (Box 52.2).

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

A pleural effusion is frequently identified during evaluation of the underlying chief complaint of the patient. Because the etiology of pleural effusion is myriad, a thorough history and physical examination may narrow the differential diagnosis substantially. Box 52.3 lists the common causes of pleural effusion. Frequently, effusion is identified on physical examination or with basic chest radiography, but additional imaging modalities, including radiography, ultrasonography, and computed tomography (CT), may identify the cause and provide additional insight about the effusion.1,3,6

Diagnostic Considerations

Radiography

Erect posteroanterior and lateral chest radiographs are still the most important initial tools in the diagnosis of a pleural effusion. On upright and lateral decubitus films, loss of the costophrenic angle is seen. With increasing size of the pleural effusion, the hemidiaphragm is obscured (Fig. 52.1), and a mass effect with shift of the mediastinum away from the affected side is noted. If a film is taken with the patient supine, one may see only a nonspecific haze over the affected hemithorax because the fluid layers posteriorly. To confirm that the fluid is free flowing, lateral decubitus films with the affected side down are often obtained. With very large effusions, the affected side may remain opacified, thus rendering the decubitus film unhelpful. In adults the minimum amount of fluid required for identification of effusion on an upright film is approximately 400 mL, whereas lateral decubitus films (with the affected side down) may detect as little as 50 mL of fluid. A lateral decubitus film with the affected side up may facilitate evaluation of the underlying lung for atelectasis, a mass, or infiltrates along the lateral portion of the lung.5,6

Subpulmonic effusions are an uncommon manifestation of pleural effusions seen when fluid accumulates between the lower lung lobe and diaphragm. The fluid collection may mimic an elevated hemidiaphragm in upright imaging (Fig. 52.2). Upward of 400 mL of fluid can collect in the subpulmonic region before the posterior costophrenic sinus is filled. Evidence of an elevated hemidiaphragm with steep lateral peaks, obscured pulmonary vessels below the level of the diaphragm on a lateral projection, or a flat appearance of the posterior aspect of the hemidiaphragm on a lateral projection is suggestive of a subpulmonic effusion.6

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography is effective for visualizing an effusion and determining whether the fluid is free flowing or loculated (Fig. 52.3).7–9 In a prospective study, Piccoli et al.8 compared ultrasonography, physical examination, and radiography in patients with suspected effusions. Findings on physical examination and radiography were in agreement 76% of the time, with a kappa value of 0.52. When compared with chest ultrasonography, physical examination showed a sensitivity of 69% and a specificity of 77%. Ultrasonography may help distinguish a large solid chest mass from an effusion and can be used to guide thoracentesis. Ramnath et al.10 suggested early use of ultrasonography to identify complicated effusions (loculations or organization) because patients whose effusions were treated aggressively by decortication had significantly shorter hospital stays than did those whose effusions were treated with tube thoracostomy alone. The same study showed that in children with effusions but no ultrasonographic evidence of organization, outcomes in those receiving treatment consisting of intravenous antibiotics and drainage were similar to outcomes in those undergoing aggressive treatment such as thoracoscopy or decortication. The major advantage of ultrasonography over conventional radiography is its ability to differentiate between solid and liquid components, thereby assisting in identification of pleural fluid loculations.

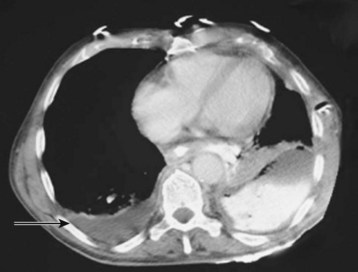

Computed Tomography

CT is rarely needed to diagnose a pleural effusion but may identify an underlying mass. In adults the presence of parietal pleural thickening on contrast-enhanced CT is a specific but insensitive indicator of an exudate. Cross-sectional imaging more clearly distinguishes anatomic compartments such as the pleural space from lung parenchyma (Fig. 52.4). Chest CT is likely to be valuable in making management decisions for complicated effusions because it can distinguish empyema from lung abscess, detect pleural masses, outline loculated fluid collections, and identify additional problems such as contusions, blebs, and infiltrates.6

Pleural Fluid Analysis

Ideally, evaluation of a pleural effusion should begin with diagnostic thoracentesis and proceed to classification of the pleural fluid as either a transudate or an exudate. The currently accepted benchmark for classifying pleural fluid, developed by Light et al.,3 is shown in Box 52.1. A number of later studies used modifications of the Light criteria but had poorer diagnostic accuracy.11

Normal pleural fluid pH has been estimated to be approximately 7.64. A pH below 7.30 suggests the presence of an inflammatory or infiltrative process,12 such as parapneumonic effusion, empyema, malignancy, connective tissue disease, tuberculosis, or esophageal rupture. According to the current American College of Chest Physicians consensus statement on the treatment of parapneumonic effusions, pH is the preferred pleural fluid chemistry test for classifying the category of a parapneumonic effusion for subsequent management (Box 52.4).13,14 Additional testing considerations for pleural fluid include cholesterol, glucose, amylase, and adenosine deaminase.11,13,14

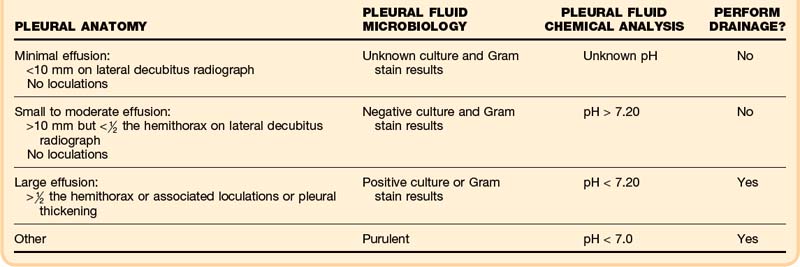

Box 52.4 Fluid Analysis of Pleural Effusions

Differential Clues

Gross blood in pleural fluid suggests tumor, trauma, or infarction.

Pleural fluid amylase elevation is associated with pancreatic disease, esophageal rupture, or malignancy.

Pleural fluid pH is normally higher than 7.30; a pH lower than 7.2 suggests an infectious process such as empyema.

Consider pulmonary emboli as the cause of loculated pleural effusions, particularly if the pleural fluid predominantly contains lymphocytes.

Treatment

Acute medical management of pleural effusions is based on both therapeutic and diagnostic considerations. In the emergency department (ED), therapeutic thoracentesis is indicated for relief of acute respiratory or cardiovascular distress. Diagnostic thoracentesis should be used in the ED to diagnose immediately life-threatening conditions in toxic-appearing patients. Circumstances outside these situations should not necessitate emergency thoracentesis, but appropriate monitoring and further medical management are essential. Table 52.1 summarizes findings dictating the appropriateness of intervention.13

Approach to Parapneumonic Pleural Effusions

Parapneumonic effusion and empyema are treated initially with empiric antibiotics according to the patient’s age and the probable organisms and sensitivities commonly present in the community. Parapneumonic effusion usually progresses through three stages. The exudative stage is associated with capillary leak during the first 3 days; the fibrinopurulent stage is associated with bacterial invasion of the pleura between days 3 and 7; and the organizational stage is characterized by fibroblast growth, occurring for 2 to 3 weeks, if the effusion is not treated properly. Lack of early diagnosis and drainage of empyema, especially in younger children, may worsen the course of disease. In a hospitalized patient with a complicated parapneumonic effusion, antibiotics are administered intravenously and a thoracostomy tube is left in place until the patient is afebrile and improving clinically. Oral antibiotics are frequently continued for weeks after these procedures.1,13

Thoracentesis: the Ideal Approach

Drainage of a pleural effusion is indicated for the following reasons:

• Diagnostic fluid or cellular analysis

• Therapeutic relief of symptomatic dyspnea

• Evaluation of complicated parapneumonic effusions or empyema

Procedural Approach

After appropriate positioning, the patient is prepared in standard sterile fashion. The effusion can be identified along the posterior infrascapular line by either clinical examination (auscultation and percussion) or bedside ultrasonography. Ultrasonography is recommended because it identifies not only the level of effusion but also the subdiaphragmatic organs that should be avoided and the depth of the fluid pocket.7,8 As the angiocatheter is advanced, the neurovascular bundles located on the inferior aspect of the ribs should be avoided. Aspiration of fluid can continue until enough fluid is obtained for diagnostic purposes or therapeutic relief.

![]() Documentation

Documentation

Identify the size and location of the effusion.

Consider the cause and duration of the effusion.

Discuss the appropriate intervention and associated risks.

Assess respiratory function before and after any intervention.

Document repeated physical examination and vital signs during the postprocedural period.

Ensure appropriate outpatient follow-up or inpatient evaluation.

Contraindications

Procedural contraindications to pleurocentesis or thoracostomy are listed in Box 52.5. Absolute contraindications include coagulopathy, known adhesions, and a history of pleurodesis. If the patient is symptomatic and coagulopathic, correction of coagulopathy and ultrasonographic guidance are recommended to minimize bleeding risks. Pleurodesis, or the introduction of a chemical or medication (talc, tetracycline, or bleomycin sulfate) into the chest cavity, triggers an inflammatory reaction over the surface of the lung and inside the chest cavity that causes the pleurae to adhere to each other and prevents or reduces further accumulation of pleural fluid. Thoracentesis should be avoided in patients at increased risk for adverse reactions as a result of unstable angina or arrhythmia or known medical noncompliance, including lack of established outpatient care. Relative contraindications include mechanical ventilation because of an increased risk for lung collapse and difficulty with positioning. In intubated patients, use of ultrasonography or CT for thoracentesis or postponing the procedure is recommended if the indication is not urgent. Patients with known bullous lung disease are at increased risk for postprocedural pneumothorax. Placement of the thoracentesis needle through a concurrent chest wall infection should be avoided because the pleural space may become seeded. A postprocedure radiograph should always be obtained to assess for pneumothorax.13,15

Complications

If the patient complains of increasing respiratory distress within the first hour after thoracentesis, RPE or pneumothorax may be occurring, and an emergency chest radiograph should be obtained. RPE is a syndrome associated with hypotension and hypoxemia. It is thought to be a result of combined alveolar-capillary membrane disruption initiated by distention, reperfusion-mediated injury, and increased pulmonary flow. Risk factors include previous atelectasis and rapid reexpansion of the lung parenchyma. Typically, a patient with significant RPE becomes symptomatic within 15 minutes to 2 hours after rapid reexpansion of the lung. Treatment is based on adequate oxygenation and circulation, generally with positive end-expiratory pressure. Concern about the potential for RPE after thoracentesis is important because mortality in patients with this condition is consistently 15% to 20% despite mechanical ventilation.16,17

Follow-Up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

In many cases, small pleural effusions are identified during evaluation of the patient’s chief complaint. Although not all effusions require immediate drainage, when thoracentesis is performed, stable patients with a clear etiology and well-established care plan may be discharged after an appropriate observation period of 3 to 6 hours. Patients with large-volume evacuation or exudative effusions or those who require further evaluation and stabilization should be admitted to the hospital.13,16

![]() Patient Teaching Tips

Patient Teaching Tips

Pleural effusions represent an underlying disease process that must be addressed.

Possible complications of pleural effusions include pneumothorax, respiratory failure secondary to massive fluid reaccumulation, septicemia, bronchopleural fistula, and pleural thickening.

Follow-up is recommended for all patients undergoing thoracentesis. Some experts recommend serial chest radiographs to ensure clearing. Some perform computed tomography after plain radiographs show clearing.

Tips and Tricks

Establish bedside ultrasonography as part of assessment for pleural effusions.

Consider pulmonary embolism with an uncertain pleural effusion etiology.

Ultrasound-guided thoracentesis enhances visualization and minimizes complications.

Complicated pleural effusions may require surgical intervention.

“Two-test” and “three-test” rules for pleural fluid analysis exist but are not as specific as the Light criteria.

Neustein SM. Reexpansion pulmonary edema. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2007;21:887-–91.

Sahn SA. The value of pleural fluid analysis. Am J Med Sci. 2008;335:7–15.

Sartori S, Sombesi P. Emerging roles for transthoracic ultrasonography in pleuropulmonary pathology. World J Radiol. 2010;2:83–90.

Thomsen TW, DeLaPena J, Setnik GS. Thoracentesis. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:e16.

1 Celli RB. Diseases of the diaphragm, chest wall, pleura and mediastinum. Cecil RL, Goldman L, Ausiello D. Cecil textbook of medicine, 22nd ed, Philadelphia: Saunders, 2007.

2 Guyton AC. Pulmonary circulation, pulmonary edema, and pleural fluid. Guyton AC, Hall JE. Textbook of medical physiology, 11th ed, Philadelphia: Saunders, 2006.

3 Light RW, MacGregor MI, Luchsinger PC, et al. Pleural effusions: the diagnostic separation of transudates and exudates. Ann Intern Med. 1972;77:507–513.

4 Tu CY, Hsu WH, Hsia TC, et al. Pleural effusions in febrile medical ICU patients: chest ultrasound study. Chest. 2004;126:1274–1280.

5 Blackmore CC, Black WC, Dallas RV, et al. Pleural fluid volume estimation: a chest radiograph prediction rule. Acad Radiol. 1996;3:103–109.

6 Desai SR, Wilson AG. Pleura and pleural disorders. Hansell DM, Lynch DA, McAdams HP, et al. Imaging of diseases of the chest, 5th ed, London: Mosby, 2010.

7 Sartori S, Sombesi P. Emerging roles for transthoracic ultrasonography in pleuropulmonary pathology. World J Radiol. 2010;2:83–90.

8 Piccoli M, Trambaiolo P, Salustri A, et al. Bedside diagnosis and follow-up of patients with pleural effusion by a hand-carried ultrasound device early after cardiac surgery. Chest. 2005;128:3413–3420.

9 Tayal VS, Nicks BA, Norton HJ. Emergency ultrasound evaluation of symptomatic nontraumatic pleural effusions. Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24:782–786.

10 Ramnath RR, Heller RM, Ben-Ami T, et al. Implications of early sonographic evaluation of parapneumonic effusions in children with pneumonia. Pediatrics. 1998;101:68–71.

11 Sahn SA. The value of pleural fluid analysis. Am J Med Sci. 2008;335:7–15.

12 Mishra EK, Rahman NM. Factors influencing the measurement of pleural fluid pH. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2009;15:353–357.

13 Colice GL, Curtis A, Deslauriers J, et al. Medical and surgical treatment of parapneumonic effusions: an evidence-based guideline [ACCP consensus statement]. Chest. 2000;118:1158–1171.

14 Heffner JE, Highland K, Brown LK. A meta-analysis derivation of continuous likelihood ratios for diagnosing pleural fluid exudates. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:1591.

15 Thomsen TW, DeLaPena J, Setnik GS. Thoracentesis. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:e16.

16 Neustein SM. Reexpansion pulmonary edema. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2007;21:887–891.

17 Feller-Kopman D, Berkowitz D, Boiselle P, et al. Large-volume thoracentesis and the risk of reexpansion pulmonary edema. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;84:1656–1661.