CHAPTER 19 Plastic surgery and skin

Providing skin cover

Flaps

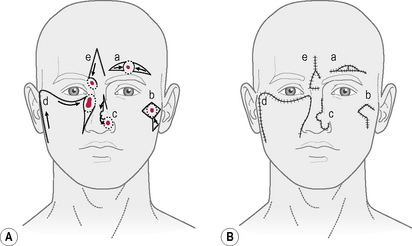

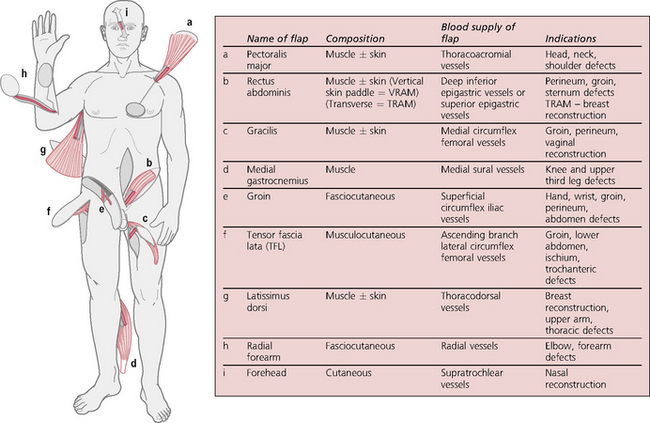

A flap is a section of tissue transferred, carrying its own blood supply. They can be defined by their composition, e.g. skin (cutaneous), fasciocutaneous, adipofascial, or muscle with or without skin or bone. They can be local (raised from an area sharing a border with the defect) and move by advancement, rotation or transposition. These can be geometrically designed to rely on the unnamed vasculature from the base of the flap (random pattern → Fig. 19.1) or based on a named or identified vessel – the pedicle, e.g. groin flap, deltopectoral flap or on a vessel perforating from the deeper tissues. These pedicled flaps do not necessarily share a border with the defect (regional), and can be moved into the defect around a pivot point, related to the axis around the pedicle. General indications for flap cover include: avascular areas, e.g. exposed bone or joint surfaces, exposed major blood vessels, irradiated areas or areas to undergo radiotherapy. (For a selection of pedicled flaps, see Figure 19.2.)

Free flaps

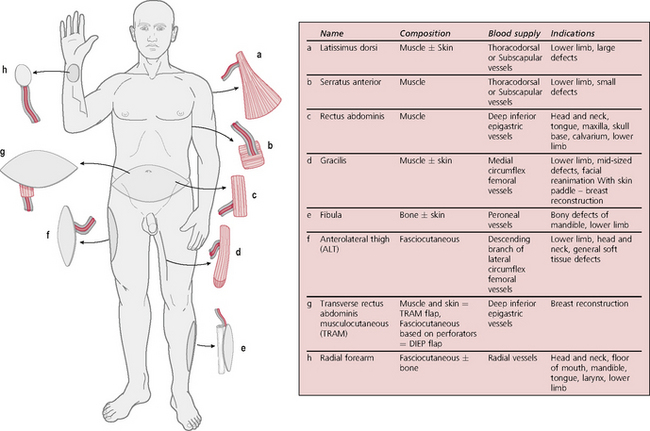

The blood supply to the flap is completely divided and the flap transferred to another area of the body where revascularization is affected by microvascular anastomosis. Free flaps may be composed of muscle, fasciocutaneous tissue, bone (e.g. fibula, scapula, iliac crest, radius) or a combination of these. Advantages include single-stage reconstruction, a wide choice of donor sites allowing better tailoring and choice of a flap to suit the defect without the constraint of a fixed pedicle and a good success rate (up to 95%). Disadvantages include long operating time and the need for specialized equipment and expertise. (For a selection of free flaps, see Figure 19.3.)

‘Surgical’ skin lesions: principles of management (→ Table 19.1)

| Benign | |

| Epidermis | Pedunculated papilloma, wart, seborrhoeic keratosis, keratoacanthoma |

| Dermis | Pyogenic granuloma, fibrous histiocytoma, keloid |

| Appendages | Furuncle, carbuncle, hidradenitis suppurativa, sebaceous cyst, dermoid cyst, pilonidal sinus |

| Subcutaneous | Lipoma, neurofibroma |

| Melanotic | Intradermal naevus, blue naevus, compound naevus, spitz naevus, congenital naevus |

| Vascular | Campbell de Morgan spots, haemangiomas, capillary/venous/arteriovenous/lymphatic malformations, spider naevi, glomus tumours |

| Premalignant | |

| Epidermis | Actinic (solar) keratosis, Bowen’s disease, erythroplasia of Queyrat (penis) |

| Malignant | |

| Epidermis | Basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma |

| Dermis | Kaposi’s sarcoma, secondary deposits |

| Appendages | Sebaceous carcinoma (rare), sweat gland carcinoma (rare) |

| Subcutaneous | Liposarcoma, neurofibrosarcoma |

| Melanotic | Malignant melanoma |

| Vascular | Angiosarcoma (rare) |

Common benign lesions

Epidermis

Skin appendages

Boil (furuncle)

Pilonidal sinus

Disorders of the nails

Ingrowing toenail (IGTN)

Treatment

Infected

Malignant lesions

Epidermis

Basal cell carcinoma (rodent ulcer)

There are several different types:

Melanocytic lesions

Benign lesions

Naevi

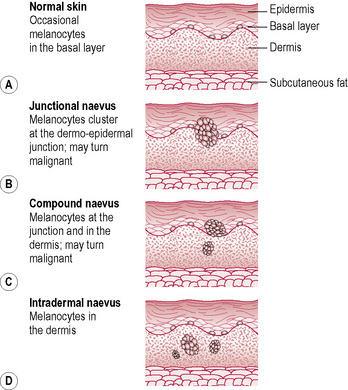

The position of melanocytes can give rise to a number of pigmented lesions:

Malignant melanoma

Classification

Staging

Treatment

Lesions of vascular origin

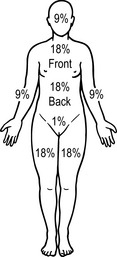

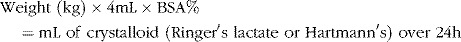

Burns

Management of burns

First aid

Assessment of the patient

Hand injuries

Hand infections

Cosmetic (aesthetic) surgery

Reconstructive breast surgery

Other types of surgery

Cleft lip and palate

Treatment

Various relaxing or plastic procedures may be necessary to achieve this.

Prognosis

Surgery for cleft lip and cleft palate is confined to some 10 centres nationally. A good cosmetic result is normally achieved in closing cleft lip. With cleft palate, satisfactory speech is achieved in about 80% of cases; however 20% may require a pharyngoplasty due to velopharyngeal incompetence (abnormal nasal escape during speech, nasal regurgitation of fluids). All children need speech therapy. Occasionally, secondary procedures may be required such as secondary alveolar bone grafting at 9–11 years and corrective rhinoplasty around the age of 16 years. The Cleft Lip & Palate Association (www.clapa.com) is available for advice and support.