Plastic surgery

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Prepare

1. In the region of the proposed operation, identify the lines of tension within the skin described by the Professor of Anatomy in Vienna, Carl Ritter von Langer (1819–1887). Try to make all incisions parallel to these lines. When this is not possible, consider using a Z-plasty or local flap in closing the wound to help prevent the formation of scar contracture postoperatively.

2. When planning a large flap or a sophisticated reconstruction, mark out a plan of the flap on the patient with a skin marker the day before operation. For smaller flaps and simple incisions, mark out the area of incision on the patient after preparing the area, before incising the skin. Use a fine pen and ink for marking out the lines of incisions on the face. Use a broad proprietary marking pen in other areas. Try to follow these lines, as they provide a useful guide once the skin has been incised and tension in the surrounding skin has changed. Be prepared, however, to make adjustments on occasions according to the circumstances.

3. While general anaesthesia is now very safe, do not forget that many operations can be carried out under regional anaesthesia or local anaesthesia (see Chapter 2), especially on the hand, including cases of replantation. Large areas of split skin graft can be taken from the lateral aspect of the thigh by infiltrating the lateral cutaneous nerve of the thigh in the region of the inguinal ligament with local anaesthetic. Many other procedures can be carried out under regional anaesthesia, if necessary with the assistance of a sedative. Many simple skin lesions can be excised under local anaesthesia with 1% lidocaine. To excise small lesions in the head and neck region, where the skin is highly vascular, use 2% lidocaine with 1:80 000 adrenaline (epinephrine). Wait 5 minutes after injecting the mixture, to provide a relatively avascular field as well as anaesthesia. When carrying out extensive excisions of the face or scalp under general anaesthesia, inject a dilute solution of 0.5% lidocaine with 1:200 000 adrenaline (epinephrine).

Technique

Sutures

1. On the face, approximate the deep dermis of the skin edges with interrupted 5/0 polyglactin sutures. Accurately appose the skin edges with 6/0 interrupted nylon sutures. Remove them on the third or fourth postoperative day. If they remain longer, suture marks form, which are unsightly and may prove impossible to remove.

2. Elsewhere on the body, approximate the deep dermis of the wound edges with 3/0 polyglactin sutures and use subcuticular polypropylene sutures whenever possible, tying a knot at either end to prevent slipping. Leave these sutures in for 10 days, or longer if there is a tendency for the scar to stretch because of its site.

Instruments

1. Respect tissues and their viability by handling them with care and using the appropriate instruments. Control and steady the skin with skin hooks or fine-toothed forceps. Do not crush it by grasping it with non-toothed forceps.

2. For accurate suturing, use a fine needle-holder with a clasp that feels comfortable. Practise using needle-holders with their own cutting edges for cutting sutures so you can use them effectively. They are particularly useful when you are inserting many interrupted sutures, the accuracy of which is not crucial to the overall result.

SKIN COVER

1. Close skin wounds primarily to provide ideal skin cover following incisions of the skin, excisions of skin lesions and simple lacerations.

2. Use split skin grafts to repair wounds with significant skin loss, to avoid skin closure with tension, or following trauma with an appreciable degree of crush injury to the local tissues. Skin graft survival depends on adequate vascularity of the base of the wound.

3. Use skin flaps, which carry their own blood supply and are temporarily self-sufficient, in primary or secondary repair or reconstruction. Use them as primary cover for vital structures such as exposed neurovascular bundles or for structures that have an inadequate blood supply to support a graft, such as bare bone, bare cartilage, bare tendons and exposed joints.

SKIN CLOSURE

Action

1. Whenever possible, make incisions following the direction of the tension lines, particularly on the face.

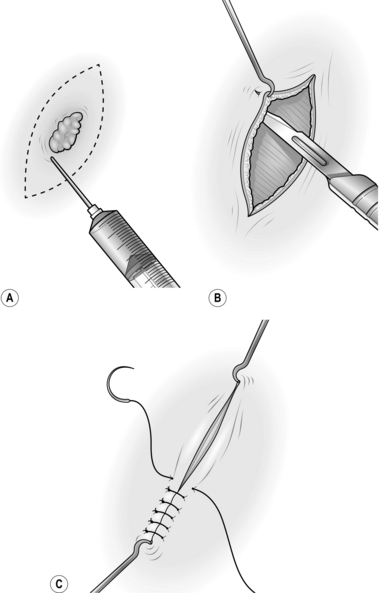

2. For excisions, mark the skin in ink, planning to excise the minimal necessary amount of tissue. Draw an ellipse with pointed ends around this mark, parallel to the tension lines (Fig. 33.1A).

3. On the face, inject the surrounding tissue with 2% lidocaine and 1:80 000 adrenaline (epinephrine) and wait 5 minutes for both components to take effect.

4. Make a vertical cut through the skin along the lines of the ellipse. Ensure that you adequately clear the lesion in depth.

5. Undermine the skin edges beneath the layer of subcutaneous fat to facilitate approximating the edges without tension (Fig. 33.1B).

6. Place a skin hook in each end of the wound and ask your assistant to draw them apart. This manoeuvre approximates the edges (Fig. 33.1C).

8. Apply a small dressing, or use no dressing at all if practical.

SKIN GRAFTS

Appraise

1. A skin graft (Greek: graphion = a style; something inserted) is a piece of skin detached from its donor site and transferred to a recipient site. It may contain part of the thickness of the skin (a split skin graft, described by the German surgeon Karl Thiersch in 1874) or the full-thickness graft of skin, described in 1874 by the Austrian ophthalmologist John Wolfe, who settled in Glasgow.

2. A skin graft depends for its survival on receiving adequate nutrition from the recipient bed. Thus, thin split skin grafts survive more readily than thick split skin grafts or full-thickness grafts.

3. If there is a poor vascular bed, or infection, no graft will survive. In these cases prepare the graft bed appropriately with dressings (see below), or consider using a flap.

4. Choose an appropriate donor site for each individual patient.

SMALL SPLIT SKIN GRAFT

Appraise

1. A split skin graft is a sheet of tissue containing epidermis and some dermis taken from a donor site. It is obtained by shaving the skin with an appropriate knife or blade. A layer of deep dermis is preserved at the donor site and, when dressed appropriately, this is re-epithelialized from residual skin adnexae.

2. Use a small split skin graft to repair traumatic loss of small areas of skin from the hand or fingers, and occasionally in other parts of the body. Avoid using them on the tips of the thumb and index fingers since they tend to become hyperaesthetic.

3. Choose the donor site carefully. On the upper limb prefer skin from the medial aspect of the arm where the donor site is inconspicuous; on the forearm an ugly resultant scar may be visible.

Action

1. Mark out on the medial aspect of the arm an area of skin which is more than sufficient to cover the recipient site.

2. Inject 2% lidocaine and 1:80 000 adrenaline (epinephrine) intradermally into and beyond the marked area and wait for 5 minutes.

3. Lubricate the marked area with liquid paraffin.

4. Grip the arm on the lateral aspect with your left hand so that the skin which is marked out becomes tense, with a convex surface.

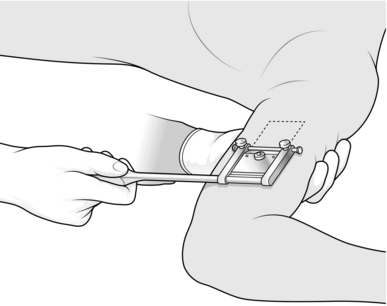

5. Cut the graft from the marked area using a Da Silva knife (Fig. 33.2).

6. Dress the donor site with a calcium alginate dressing, one layer of paraffin gauze, several layers of dressing gauze and a crepe bandage.

7. Apply the split skin graft directly on to the recipient site, spread it and anchor it using a minimal number of sutures.

8. Apply paraffin gauze, dressing gauze and a crepe bandage.

LARGE SPLIT SKIN GRAFT

Appraise

1. Use these grafts following extensive skin loss from burns, trauma or radical excisional surgery.

2. Adequately prepare the recipient site to ensure a good ‘take’ of the graft. Grafts take best on exposed muscle or well-prepared granulation tissue. They do not reliably survive on exposed fat where there is a poor vascular supply.

3. The take of a graft can be improved in certain circumstances by meshing it, quilting it, or by delaying its application and then exposing it. These are described below.

4. Use an electric dermatome, if available, to harvest the graft using the same principles outlined below.

Prepare

1. Following ‘cold’ surgical excisions apply pressure to obtain haemostasis. Avoid diathermy if possible since skin grafts do not take over diathermy burns.

2. Where subcutaneous fat is exposed, suture the overlying skin down to the muscle or deep fascia to cover it.

3. For infected wounds, take swabs for bacterial culture and prepare the recipient site with dressings of Eusol (Edinburgh University solution of lime) and paraffin. Change them 3–4 times a day. The recipient site is ready to receive a graft when it appears healthy and compact and has red granulation tissue with minimal exudates.

4. Choose the donor site most readily available to provide a large area of skin graft; this is usually the thigh. In young people, use the inner aspect of the thigh, where the donor site will be hidden. In elderly people, use the outer aspect of the thigh, where the skin is slightly thicker, so that if healing is delayed the wound is accessible and is easily managed.

Action

1. Prepare both recipient and donor sites by applying skin antiseptic.

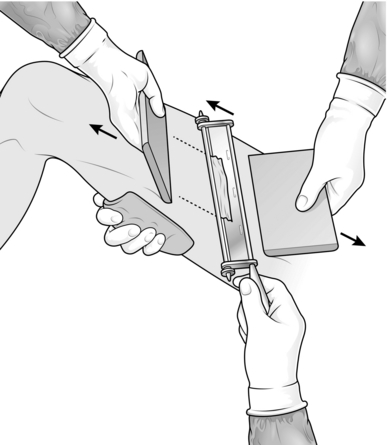

2. Have your assistant spread a large swab on the side of the thigh opposite to the proposed donor site. With a hand on the swab it is possible to support the thigh and tense the skin at the donor site by gripping the skin firmly with the swab.

3. Set the blade on the Watson knife to take the appropriate thickness of skin graft. Use a medium setting at first and then adjust it accordingly.

4. Apply liquid paraffin on a swab to the donor site and along the knife blade.

5. Ask your assistant to hold the edge of a graft board at the starting point with the other hand (Fig. 33.3).

6. Cut a skin graft with the Watson knife, holding a board in your non-cutting hand and advancing this a few centimetres in front of the knife. Start with the knife at 45° to the skin and once the blade has entered the dermis rotate it axially so that it runs just parallel with the skin surface. Use a ‘sawing’ action with the knife, advancing the blade only a few millimetres at a time. When you have harvested an adequate length of skin, turn the blade upwards and cut the graft off with one firm movement. If the graft is not detached with this movement, cut along its base with a pair of scissors.

7. Place the skin graft, outer surface downwards, on a damp saline swab and make sure that you have obtained sufficient skin; in case of doubt, take another strip of split skin.

8. Dress the donor site with calcium alginate dressing, one layer of paraffin gauze, dressing gauze, cotton wool and a crepe bandage.

9. Apply the skin graft to the recipient defect, ensuring that it is placed with its cut surface applied to the wound. The outer surface is opaque, the inner surface is shiny. Spread it, using two pairs of closed non-toothed forceps.

10. Cut off the surplus skin at the wound edge, leaving a margin of 3 mm around the periphery.

11. If the skin has been applied on a site to which you can apply a satisfactory compression dressing, do not use sutures.

12. Dress with several layers of paraffin gauze, dressing gauze, wool and crepe bandage, immobilizing the joints above and below the graft with a bulky dressing.

13. In areas where it is difficult to apply a compression dressing, immobilize the graft with interrupted sutures at the edge or insert a circumferential continuous suture around the graft.

14. Dress with paraffin gauze, dressing gauze, wool and strips of adhesive dressing.

15. Keep the graft site elevated postoperatively.

16. For grafts on the lower limb below the knee, do not allow the grafted area to be dependent for 7 days; fluid will collect between the graft and the base unless the graft is meshed. Then arrange progressive mobilization with compression support to the leg and foot, including the graft.

DELAYED EXPOSED GRAFTS

Appraise

1. Use a delayed graft when the graft in its recipient site can be exposed indefinitely by the patient without being disturbed.

2. Apply a delayed graft to surgical wounds when haemostasis is difficult to establish perioperatively. Since the graft is exposed, it can be monitored regularly to ensure that it has taken.

Action

1. Prepare the recipient site during the operation to excise all dead or doubtful tissue and any foreign material, after achieving haemostasis.

2. Dress with several layers of paraffin gauze, dressing gauze, wool and a crepe bandage.

3. Harvest large split skin grafts adequate to cover the defect and dress the donor site (see below).

4. Spread the split skin graft on paraffin gauze with the external opaque surface on the gauze. Fold and wrap this in a saline-soaked swab and place it in a sterile jar to be stored in a refrigerator at 4 °C.

5. On the following day, remove the dressing from the recipient site.

6. Apply the skin graft to the defect and spread it to cover all areas. Trim and store any excess skin at the margin.

7. Remove the paraffin gauze and leave the skin graft exposed.

8. Observe the graft at regular intervals. If serum collects beneath it, roll this out with cotton wool budded sticks soaked in saline, either to the edge or through a small incision made in the graft.

9. Be sure that the exposed area is well protected from any injury, particularly while the patient is asleep.

MESHED GRAFTS

Appraise

1. Meshed grafts are useful for providing skin cover to large areas, particularly when there is limited availability of donor skin, as often occurs in extensive burns.

2. They survive more reliably, as any underlying seroma that collects escapes through the interstices of the graft, leaving the graft elements intact.

3. They are effective in covering irregular surfaces as they can be moulded to these.

4. Unfortunately the resultant appearance is less satisfactory than a sheet graft.

Action

1. Prepare the donor site in the usual way.

2. Harvest long, thin strips of split skin graft, as described above.

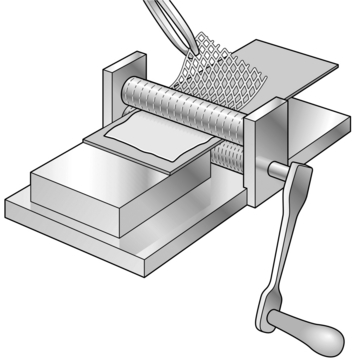

4. Pass the skin graft through the skin mesher. It may need to be placed on a carrier for this, depending on the type of instrument (Fig. 33.4).

5. Apply the mesh graft directly on to the recipient site using two pairs of non-toothed forceps.

6. Spread the skin out appropriately to cover all suitable recipient areas.

7. Suture the graft with continuous sutures at the periphery only if the area is difficult to dress.

8. Dress the area with a calcium alginate dressing, one layer of paraffin gauze, dressing gauze, cotton wool and crepe bandage.

10. Continue to re-dress at approximately 3-day intervals until the interstices have epithelialized.

QUILTED GRAFTS

Action

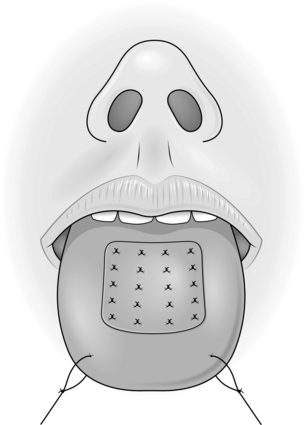

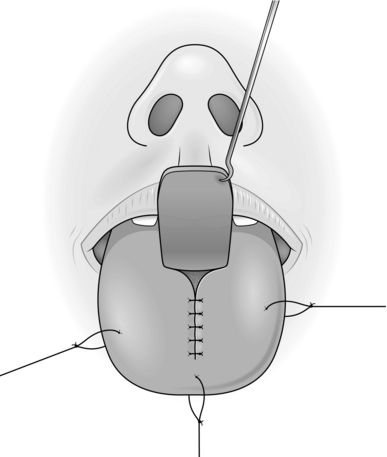

3. Put two large sutures in the anterior aspect of the tongue and pull it forwards.

4. Apply the skin graft to the tongue and trim the excess at the edges.

5. Place multiple 3/0 absorbable sutures at the edge of the graft and throughout its surface (Fig. 33.5).

FULL-THICKNESS GRAFTS

Appraise

1. These give better cosmetic results than split-thickness grafts as they contract less. The quality of the skin is better but they need a very good vascular bed in order to survive.

2. Their most common application is on the face following excision of small lesions, and the best results are achieved in the eyelid region and around the medial canthus.

3. They can occasionally be used on the hand, but are not generally used elsewhere, as large grafts leave a large primary defect.

4. The best donor sites are those with surplus skin so that the skin can be closed primarily with an insignificant scar. The most common donor areas are post-auricular, pre-auricular, upper eyelid, nasolabial and supraclavicular skin.

Action

1. Mark the area of skin to be removed and measure it.

2. Mark out a similar area in the donor site, allowing an extra 2.5 mm or more at each margin for the contour difference that will be present at the recipient site.

3. Plan an ellipse at the donor site around the proposed graft to allow primary closure.

4. Inject local anaesthetic at the excision and donor sites.

5. Create the defect at the recipient site.

6. With a size 15 blade, cut around the margins of the planned donor skin.

7. Raise the full ellipse of skin and subcutaneous tissue.

8. Undermine the skin edges at the donor defect and close this primarily.

9. Place the skin graft on to a wet saline swab, skin surface down.

10. Using small, curved scissors cut the subcutaneous fat off the skin graft and excise the redundant skin.

11. Place the skin graft into the defect and suture the edges at the periphery. Leave the suture ends long.

12. Use tie-over sutures to fix the dressing of paraffin gauze and proflavine wool.

COMPOSITE GRAFTS

Action

1. Mark out the defect that will be left after excision of diseased or damaged skin, with excision of traumatized or contaminated wound edges, if necessary.

2. Identify a site on either pinna that corresponds in both size and shape to the planned defect.

3. Mark out this area with ink.

5. Plan the reconstruction of the donor defect.

6. Inject 0.5% lidocaine and 1:200 000 adrenaline (epinephrine) into both sites and wait for 5 minutes.

RANDOM PATTERN SKIN FLAPS

Introduction

1. Skin flaps are used to repair or reconstruct defects where there is an inadequate blood supply to support a skin graft. They survive on their own blood supply, which they bring with them, and this may be beneficial to the recipient site. It may help by introducing a new blood supply to an avascular area following irradiation, or to a fracture site where there is delayed union.

2. The quality of the skin in a skin flap is almost normal and its texture and cosmetic appearance are much better than a graft. A skin flap may, however, lose its nerve supply and have its vascular supply and lymphatic drainage partly compromised in the transfer.

3. Until relatively recently, all skin flaps were based on a random vascular pattern. It was recognized that flaps with a length greater than their base would survive in certain areas. It is now realized that the reason for this survival is that these flaps had, unknowingly, been based on an axial pattern basis. If a flap is designed around a recognized artery and vein, with these vessels passing down its central axis, it may be safely transferred with a very large length-to-breadth ratio. Indeed, the breadth need be the artery and vein alone, providing they remain patent.

4. Many of the superficial muscles of the body have one principal vascular hilum, and these muscles can be rotated about the hilum on a single pedicle. It has further been realized that the skin overlying these superficial muscles receives its vascular supply from them. Consequently, the muscle with its overlying skin can be transposed as a single unit, forming a myocutaneous flap. A large number of these flaps have been described, but the more commonly used ones alone will be described below.

5. Special terms are traditionally used in relation to flaps. Delay indicates partial division of a flap at its base and re-suturing. This procedure encourages an improved blood supply to the flap from the opposite attachment. Complete division at the base carried out a few days later is then usually safe. After a flap has been transferred safely, the bridging portion may be divided. The two ends are trimmed and one is sutured into the new recipient area while the other is replaced in the donor site. This is referred to as in-setting.

6. When planning a flap, it is useful to employ a sheet of sterile paper or other similar material to act as a template. This can be cut to shape and used as a trial flap.

Z-PLASTY

Appraise

1. Z-plasties are used for releasing linear contractions. These usually develop along linear scars that traverse Langer’s lines.

2. These linear contractions are often most evident when crossing the concavity of the flexor aspect of a joint, but they can occur on extensor surfaces and in other areas unrelated to joints.

Action

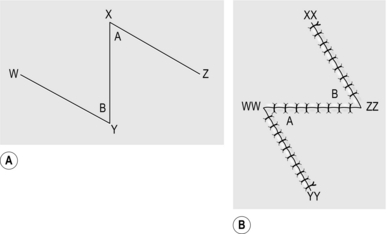

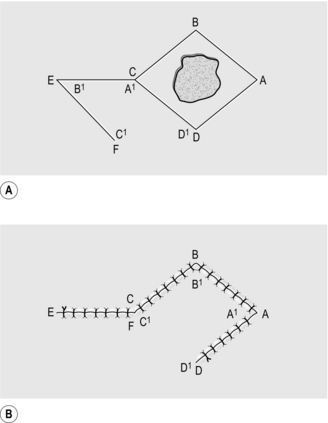

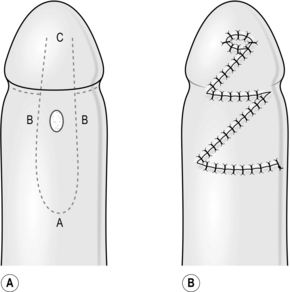

1. Draw a line along the full extent of the contracture (Fig. 33.6).

2. From one end, draw a line at 60° to the first line and of the same length.

3. From the opposite end, draw a line at 60° on the opposite side of the line for the same length.

4. Incise along the central line and excise any scar tissue.

5. Incise along the two lateral lines through the full thickness of skin and subcutaneous tissue.

6. Raise the flaps so formed, lifting the skin and subcutaneous tissue as one, holding the tip of each flap with a skin hook.

7. Interchange the two skin flaps.

8. If the flaps do not meet comfortably, undermine the skin and subcutaneous tissue around the periphery of the wound to allow them to lie correctly.

9. Suture the tips of the two flaps into place first.

Technical points

1. The angle of the Z-plasty can be varied according to circumstances.

2. If the scar contracture is particularly long, use two or more Z-plasties, either in series or at intervals along the length of the contracture.

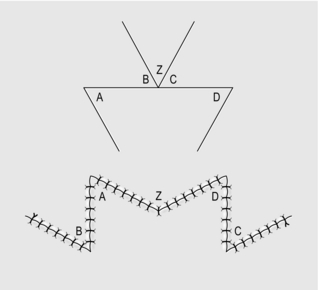

3. For scar contractures across a web space, use a W-plasty (Fig. 33.7). This consists of two Z-plasties, placed in reverse direction to each other, meeting at the base of the web space.

TRANSPOSITION FLAP

Appraise

1. Small transposition flaps on the face have long been used. It is well recognized, that in this region, because of the vascularity of the skin, flaps with a large length-to-breadth ratio can be used safely.

2. Transposition flaps allow skin from an area of abundance to be moved to a defect where primary closure is inappropriate.

3. On the face, there is an abundance of skin appropriate for transposition flaps in the nasolabial area, the glabellar area and the upper eyelid.

4. In other parts of the body, many axial pattern flaps are used as transposition flaps.

Action

1. Mark out the defect in ink.

2. Plan the transposition flap in an adjacent area with superfluous skin and mark this out (Fig. 33.8).

3. Check that the margin of the flap most distal from the defect is long enough from the fulcrum at its base to reach the most distal part of the defect. This is the limiting factor of the flap.

4. Excise the lesion to create the defect.

5. Raise the flap, including skin and subcutaneous tissue, and support the tip of the flap on a skin hook.

6. Transpose the flap into the defect and check that it fits.

7. Undermine the edges of the donor site defect and also the edges of the excision area to allow the flap to sit more comfortably in the defect.

8. Close the donor defect in layers.

10. Leave the flap exposed if possible, so you can monitor it.

RHOMBOID FLAP

Appraise

1. A rhomboid flap is, as its name suggests, a flap with the shape of an equilateral parallelogram – a lozenge shape.

2. The rhomboid flap is most useful when the appropriate ellipse for excision of a defect is at right-angles to Langer’s lines. It has a similar effect to a transposition flap carried through 90°.

ROTATION FLAP

Appraise

1. These are large flaps used to close relatively small defects.

2. They use excess skin at a distance from the defect and borrow small amounts of skin from a large area.

3. They are principally used to borrow skin from the neck to take up to the face. They can be used on the scalp and for treating sacral pressure sores.

Action

2. Draw an isosceles triangle around the defect, with the apex of the triangle at or pointing towards the centre of the arc of rotation of the flap (Fig. 33.10).

3. Draw the arc of the rotation flap.

4. Raise the skin and subcutaneous tissue of the flap.

5. Undermine the skin at the edge of the defect and along the skin margin opposite the flap.

6. Rotate the flap into the defect.

8. If necessary, excise a wedge of tissue along the skin edge opposite the flap to assist rotation. If necessary, ‘cut-back’ into the flap at the opposite end of the arc of the flap from the defect, to create a better fit.

ADVANCEMENT FLAP

Action

2. Mark out the smallest possible square or rectangle enclosing this defect, with lines parallel and at right-angles to Langer’s lines.

3. Extend the marks of the sides running parallel to Langer’s lines in each direction from the defect, thus delineating two flaps (Fig. 33.11).

EXPANSION FLAP

Appraise

1. These flaps are used specifically for repairing and reconstructing defects of the scalp.

2. Flaps on the scalp are notorious for their inability to stretch because of the inelasticity of the galea (Latin: = a helmet).

3. Division of the galea allows some stretching of the skin to take place, especially in younger patients.

Prepare

1. Pay particular attention to the preoperative planning of the flap. Remember that the scalp flap will move in three dimensions.

2. Shave the patient’s hair over the whole scalp to a length of 1 cm. Leave long locks of hair only if you can confidently cope with these during the operation.

3. Make a careful plan of the flap to be used, and mark the outline of this.

4. Completely shave the hair for 1 cm on either side of this line and for 1 cm around the outline of the defect.

5. Wash the hair thoroughly to remove all cut and shaved hairs.

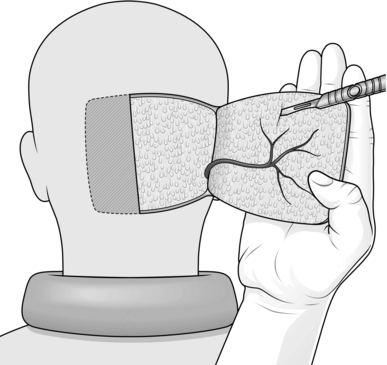

Action

1. Place the patient, face downwards, on the operating table. Use a neurosurgical head-rest to support the head, if this is available.

2. Mark out the defect on the scalp.

3. Mark out the flap as previously planned. The flap may be of transposition, rotational or advancement design.

4. Plan a wide base to the flap around the periphery of the scalp to ensure that at least one principal vascular system enters its base.

5. Inject the planned outline of the flap with 0.5% lidocaine and 1:200 000 adrenaline (epinephrine) and wait at least for 5 minutes.

6. Excise the lesion and create the defect.

7. Incise along the margins of the flap to elevate it with the underlying galea so that this is included with the flap.

8. Reflect the flap backwards, exposing the galea.

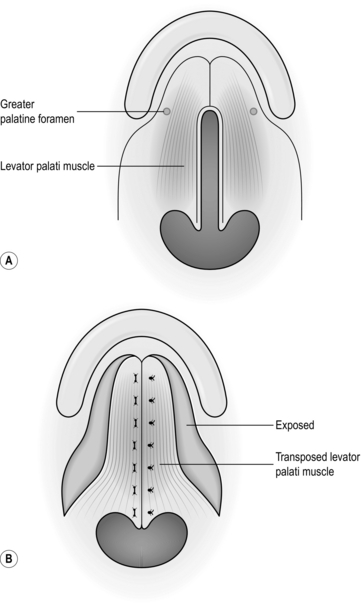

9. Support the flap on the palm of the hand and make multiple incisions just through the galea with a no. 15 blade, across the full width of the flap (Fig. 33.12).

10. Identify the principal vessels beneath the surface of the galea and avoid dividing them.

11. Make multiple transverse incisions at right-angles to the first set, along the whole length of the flap.

12. Reflect the flap back into the defect.

13. Suture the flap into place with one layer of 3/0 non-absorbable sutures.

14. Always insert suction drains under the flap.

15. Dress with paraffin gauze, dressing gauze, cotton wool and crepe bandages.

16. Re-dress after 48 hours and, if possible, leave exposed.

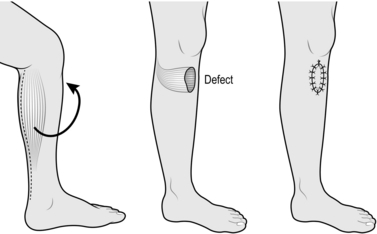

CROSS-LEG FLAP

Appraise

1. This used to be the most commonly used flap to cover open (compound) fractures of the tibia and fibula with extensive soft tissue loss.

2. There are now many fascio-cutaneous and free flaps described that are more suitable but, on rare occasions, cross-leg flaps may be useful.

3. Cross-arm flaps and cross-thigh flaps can be created using the same principle.

Prepare

1. Mark out the minimal defect on the leg.

2. Plan a flap from the calf of the donor leg, based medially, preserving the long saphenous vein superiorly. Do not exceed a 1:1 length-to-breadth ratio.

3. Enlarge the defect to a size that will receive a safe flap; that is, make the defect fit the flap.

4. Using tapes, ensure that with the legs kept closely together, the flap when hinged on its medial axis will stretch to the distal part of the defect, allowing enough tissue to create a bridge between the two legs.

5. Place the patient’s legs on top of a bead bag and apply vacuum so the patient’s legs are fixed in what will be their postoperative position.

6. Maintain the patient’s legs in this bead bag for as much of the next 24 hours as is practical so that he becomes used to the position preoperatively.

Action

1. With the patient under general anaesthesia, apply a tourniquet to reduce bleeding.

2. Create the planned defect, obtain haemostasis, then remove the tourniquet from the leg.

3. Elevate the planned flap from the opposite leg, raising the deep fascia with the flap.

4. Check that with the legs in the appropriate position, the flap fits the defect.

5. Take a split skin graft from the thigh of the recipient leg and dress the donor area.

6. Apply and suture the split skin graft to the flap donor site and to the back of that part of the flap which will form a skin bridge between the two legs (Fig. 33.13).

7. Suture the four corners of the flap into place and subsequently suture the edges.

8. Dress the skin graft at the flap donor site and use minimal other dressings.

9. Splint the two legs in the bead bag and apply vacuum.

10. Ensure that there is no tension or torsion on the flap and that it is viable.

Complete

1. Perform a ‘delay’ procedure after 2 weeks using local anaesthesia only, partially dividing the base and then re-suturing this wound.

2. Take the patient back to the operating theatre after the third week and divide the flap completely under general anaesthesia, allowing a generous portion to be in-set at the recipient site.

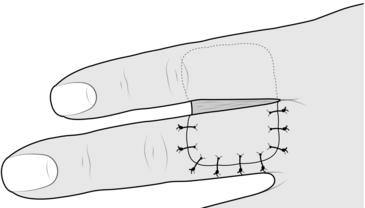

CROSS-FINGER FLAP

Action

1. Mark out the defect on the flexor aspect of the finger.

2. Apply a tourniquet and create the defect.

3. Mark out a flap on the dorsum of the adjacent finger opposite the defect, or as near as possible, avoiding the skin over the joints.

4. Elevate the rectangular flap with its base adjacent to the injured finger.

5. Place the flap over the defect (Fig. 33.14).

6. Increase the size of the defect to fit the flap.

7. Remove the tourniquet and achieve haemostasis.

8. Take a small split skin graft with a Da Silva knife.

9. Apply the skin graft to the donor defect.

10. Suture the flap into the defect.

11. Dress the wounds and splint the two fingers together after inserting some dressing gauze between the fingers.

12. Plan to divide the flap at 2 weeks, in-setting the skin bridge at both recipient and donor sites, and re-dress the wounds.

REVERSE DERMIS FLAP

Action

2. Use a tourniquet to control bleeding and create the defect.

3. Mark out an appropriate flap on the dorsum of an adjacent finger, as with a cross-finger flap.

4. Shave the planned flap with a Da Silva knife, removing a thin sheet of epidermis and superficial dermis.

5. Elevate the rectangular flap with subcutaneous tissue, leaving it attached at its base adjacent to the finger with the defect.

6. Increase the size of the defect to fit the flap.

7. Remove the tourniquet and achieve haemostasis.

9. Take a small split skin graft and apply this to the donor site and the flap.

10. Splint the two fingers together with some gauze dressing between the fingers.

11. Plan to divide the flap at 2 weeks, and in-set the bridge portion of the flap at both donor and recipient sites.

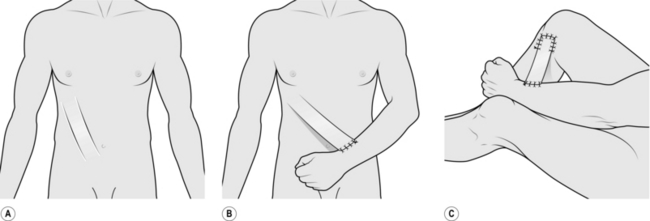

ABDOMINAL TUBE PEDICLE FLAP

Appraise

1. These flaps were formerly used as the standard technique for transferring a large amount of skin and subcutaneous tissue from the abdomen to a distant site such as the foot, the face, or elsewhere where there was extensive loss of tissue. They have been superseded almost totally by the introduction of axial pattern flaps, applied either as pedicle flaps or transferred as free flaps using microvascular surgical techniques. However, they may be useful in a few isolated situations.

2. Raise a planned rectangular area of abdominal skin and subcutaneous tissue by dividing along each side and, while still attached at each end, form the middle part into a tube. After a delay procedure, detach one end and transfer it to a wrist. When it has established a local blood supply, detach the other end and transfer it to the side of the defect. In further stages the whole flap is transferred to the defect and spread over it.

3. The patient requires approximately 5 months of hospitalization, with many operations, and failure is not uncommon at some stage.

4. Tube pedicle flaps can be raised from other sites, including the back and thigh.

ACTION

Raising the tube pedicle

1. Mark out a rectangular area 20 cm x 8 cm obliquely on the lower abdomen.

2. Incise along the long edges down to the deep fascia.

3. Dissect along the deep fascia between the two edges to elevate a bridge of skin and subcutaneous tissue.

4. Approximate the two skin edges of the bridge beneath the subcutaneous tissue to form a tube and suture as far as possible in each direction.

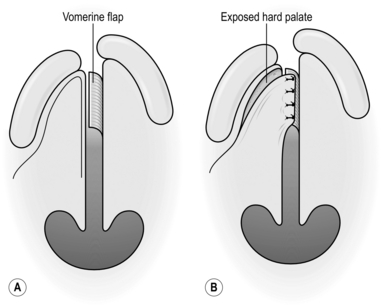

5. At either end suture the skin down to the base to create a closed tube (Fig. 33.15A).

6. Apply a large split skin graft to the residual raw area beneath the skin tube if this defect cannot be closed primarily.

Division of the tube

1. Three weeks after raising the tube, divide the base of the tube completely, passing through the delay incision.

2. Close the residual defect on the abdomen using a split skin graft if necessary.

3. Place the patient’s contralateral arm on to the abdominal wall and find a suitable recipient site at the level of the wrist to insert the tube pedicle.

4. Mark out an appropriate sized circle on the wrist.

5. Elevate the skin and subcutaneous tissue from half of this circle and reflect it backwards as a flap. This produces a circular defect.

6. Suture the free end of the abdominal tube pedicle to the circular defect (Fig. 33.15B).

7. Splint the arm to the chest wall after applying plenty of padding beneath the axilla.

Transfer of flap to defect

1. Free the abdominal tube flap from the abdominal wall by dividing the tube at its residual attachment to the abdomen, passing through the delaying incision.

2. Close the donor defect with a split skin graft if necessary, and dress the wound.

3. Transfer the arm with its attached pedicle to the site of the defect.

4. Mark out a recipient site for the tube pedicle, preferably on the distal side of the defect, so that the seam of the flap overlies the defect.

5. Create a circular defect with a healthy skin margin at the edge of the main defect.

6. Excise any scar tissue from the end of the tube pedicle, and insert the tube pedicle into the skin defect (Fig. 33.15C).

Delay of tube pedicle

Carry out a delay of the tube pedicle at the wrist end using the same technique as before.

Transfer of whole flap to defect

1. Divide the flap from the wrist, incising through the site of the delay incision.

2. Return the original skin flap from the wrist to its former site, thus leaving a residual semicircular wound, and suture this.

3. Mark out a circular area on the opposite side of the defect from the initial attachment of the tube pedicle.

4. Create a circular defect with healthy skin margins at this site.

5. Insert the free end of the tube pedicle into this defect, keeping the seam over the defect.

Insert the flap

1. Allow the flap to ‘soften’ before in-setting. This may involve waiting for 4 or 5 weeks or more.

2. Excise any doubtful tissue in the base to ensure that it is healthy.

3. Excise the seam of the tube pedicle and spread the skin of the tube pedicle over the defect.

4. Suture the edges into the edge of the defect.

5. Do not carry out any further revisions of the flap until it has been allowed to settle for at least several weeks and preferably for several months.

AXIAL PATTERN SKIN FLAPS

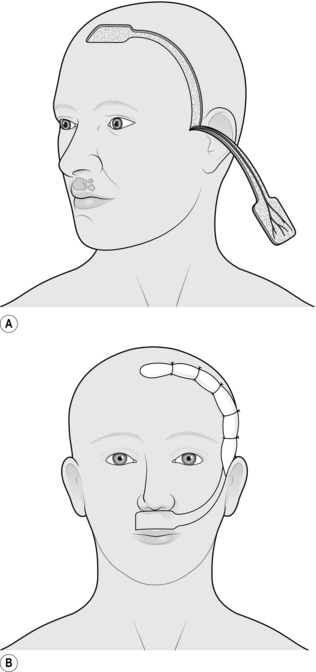

SCALP FLAP

Appraise

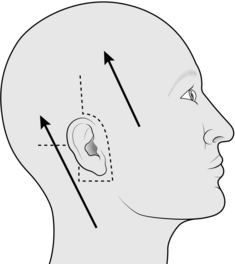

1. Scalp flaps are most commonly used for reconstructing defects of the hair-bearing skin on the face. They are usually used for reconstructing the upper lip, lower lip and chin areas in males, but there are many other occasional applications.

2. The flap is based on the posterior branch of the superficial temporal artery.

Prepare

1. Plan the flap on the day before operation.

2. Cut all the hair in the area of the operation to less than 1 cm in length.

3. Shave the hair completely in the area of the planned incisions.

4. Check that the posterior branch of the superficial temporal artery is palpable and that there are no significant scars on the scalp, suggesting previous damage to this vessel.

5. Wash the head thoroughly to remove all cut and shaved hair.

Action

2. If appropriate, increase the defect to the shape of a whole cosmetic unit.

3. If appropriate, increase the defect to make it symmetrical on either side of the midline.

4. Make a template of the defect with sterile paper.

5. With one end of a tape attached to the template, and a second fixed on the zygomatic arch below the point where the artery was palpated, swing the template up on to the vertex of the scalp using the point on the zygomatic arch as the pivot.

6. Mark out an appropriate area on the scalp behind the anterior hairline around the template.

7. Infiltrate the scalp along the marked line with 0.5% lidocaine and 1:200 000 adrenaline (epinephrine), and wait for 5 minutes.

8. Elevate the flap together with the underlying galea, starting at its distal extremity.

9. Identify the posterior branch of the superficial temporal vessels in the pedicle of the flap as it is raised, and adjust the shape of the pedicle if necessary to include these vessels (Fig. 33.16).

10. Taper the pedicle to 2 cm at its base, so that it can be rotated.

11. Transpose the flap into the defect, and in-set.

12. Cover the posterior aspect of the flap with paraffin gauze.

13. Close the donor defect primarily if possible. If it is too large, cover it with a split skin graft.

14. Plan to divide the flap at 2 weeks, providing there is a large inset. If you are in doubt, divide the flap at 3 weeks and return the pedicle.

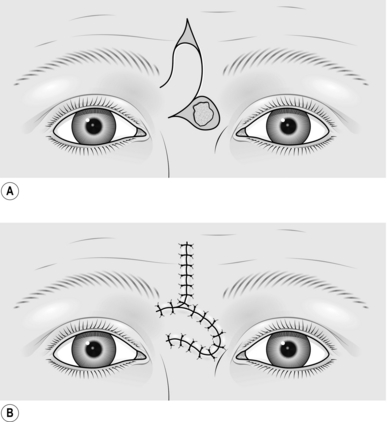

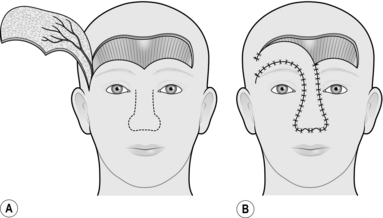

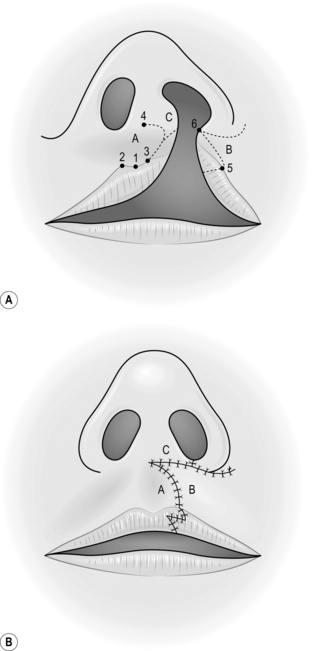

FOREHEAD FLAP

Appraise

1. The forehead flap has been used extensively in the past to provide lining of the oral cavity after major resections for tumour. It is occasionally used for resurfacing defects of the scalp and of the cheek. It is the best flap available for total nasal reconstruction.

2. It has been largely superseded by other myocutaneous and free flaps in its use for oral lining, but it remains an easy, safe and reliable flap to use, especially in the elderly and debilitated patient.

3. Its main disadvantage is the relatively poor cosmetic defect of its donor site.

4. It is not a true axial pattern flap, but it simulates one, surviving on the anterior branch of one superficial temporal artery and its accompanying vein. The distal part of the flap normally acquires its vascular supply from the opposite anterior branch of the superficial temporal artery and the supraorbital and supratrochlear vessels. When these vessels to the flap are divided, the vascular network between the branches of the various vessels is adequate to allow the flap to survive on the supply from the single vascular pedicle.

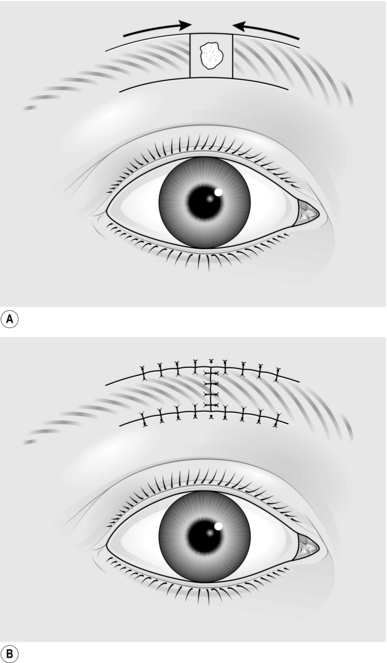

Action

1. Create the defect and measure its dimensions.

2. Mark out the flap on the forehead, making this symmetrical and preferably including the whole of the forehead skin as a cosmetic unit.

3. Increase the defect to accommodate the flap.

4. If the flap is to be used for intraoral lining, excise the coronoid process of the mandible to allow the flap to pass inside the zygomatic arch.

5. Elevate the flap, commencing at the margin distal to the flap pedicle.

6. Identify and ligate the anterior branch of the contralateral superficial temporal artery and the supraorbital and supratrochlear vessels on both sides.

7. Lift the flap in the plane beneath the frontalis muscle.

8. Identify the anterior branch of the superficial temporal artery and its accompanying veins on the undersurface of the flap, and taper the pedicle to a 2-cm margin, including these vessels (Fig. 33.17).

9. If the flap is to be used intraorally, pass this through to the mouth beneath the zygoma.

10. If there is inadequate space to carry this out, excise a segment of the zygomatic arch.

11. To avoid a further operation some 2 weeks later, shave the epidermis and superficial dermis from that part of the pedicle that will remain buried between the skin surface and the intraoral surface.

13. Use 3/0 polyglactin sutures to elevate the skin of the eyebrows on either side symmetrically.

14. Lay several layers of paraffin gauze on the donor site.

15. Harvest a large split skin graft to cover the defect in one sheet. In a young person, use the inner aspect of the arm in preference to the thigh as this gives a better colour match.

17. Apply this skin as a delayed graft 24 hours later.

18. After 2 weeks, divide the pedicle and return it, to provide symmetry to the face.

TONGUE FLAP

Appraise

1. Tongue flaps are used for repairing large palatal fistulae, providing mucosa in lip reconstruction and reconstructing defects of the pharynx and oral cavity.

2. They are not easily tolerated by young children since they are unable to co-operate. Tongue flaps are, therefore, rarely useful below the age of 6 years.

3. Most tongue flaps are not true axial pattern flaps but rely on the rich vascular network within the muscles of the tongue.

4. Flaps for palatal fistulae are taken from the dorsum, those for lining the oral cavity or the pharynx are taken from the lateral aspect, and those providing a vermilion border are taken from the anterior part. In all cases close the defect primarily.

Action

1. Create the defect and measure the dimensions.

2. Insert a large stay suture in the tip of the tongue and pull it forwards.

3. Place two large stay sutures as far to the back of the tongue as possible and use these as the principal stay sutures.

4. Plan and mark out the flap on the tongue. Flaps for palatal fistulae can be based anteriorly or posteriorly, but this depends on the position of the defect.

5. Elevate the flap of mucosa together with a sheet of muscle approximately 4–5 mm thick.

6. Check that the flap fits the defect.

7. Close the donor defect primarily (Fig. 33.18).

8. Suture the most inaccessible part of the flap into the defect first with interrupted sutures.

9. Work proximally, leaving the easiest, most anterior, suture until last.

10. Observe the flap carefully; it may require re-suturing at any time.

DELTOPECTORAL FLAP

Appraise

1. This flap, sometimes known as a Bakamjian flap after its innovator, is used for providing skin flap cover to the chin, the cheek, the region of the pinna and the neck. It can be used to provide lining to the oral cavity and pharynx but may require the development of a temporary oral or pharyngeal fistula, which is unsatisfactory.

2. When raised conventionally there is necrosis of the tip in approximately 15% of cases. Because of this and its unsightly donor defect, it has been superseded by other flaps for mucosal replacement but is occasionally useful for large skin defects.

Action

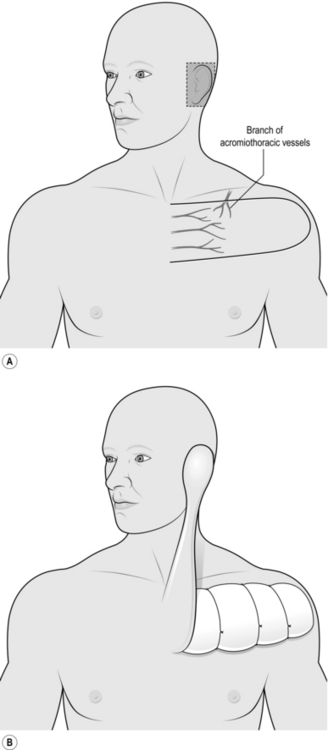

2. Mark out the flap based on the second, third and fourth perforating branches of the internal thoracic artery (Fig. 33.19).

3. Mark the upper margin of the flap along a line parallel with the clavicle, along its inferior margin. Use a line along the superior margin if a block dissection of the neck has been carried out with a McPhee incision.

4. Mark the inferior border of the flap parallel to and 10 cm below the upper border.

5. Mark the distal end of the flap as a semicircle extending to the midlateral line over the deltoid muscle.

6. Elevate the flap from its lateral margin including the fascia overlying the deltoid and pectoralis muscle.

7. Divide the branch from the acromiothoracic artery, as this perforates the clavipectoral fascia.

8. Divide and ligate the cephalic vein at the margin of the flap.

9. Reflect the flap medially to within 4 cm of the midline.

10. Dissect further medially, very carefully, to avoid dividing the perforating branches on which the flap survives.

11. Pass the flap up to the defect.

12. If the flap passes directly to the defect on the external surface, tube the intervening bridge over the neck.

13. If a block dissection has been carried out and the flap is for intraoral use, shave the epidermis from the central portion of the flap and pass the flap subcutaneously up to the defect. This manoeuvre converts the reconstruction into a one-stage operation.

14. Suture the flap into the defect.

15. Establish haemostasis on the donor site and cover it with paraffin gauze.

16. Take a split skin graft, store it and apply it to the donor site at 24 hours as a delayed graft.

17. At 3 weeks, divide the pedicle if exposed and in-set the flap.

18. Return the remainder of the pedicle to the donor site after excising the split skin graft in the appropriate area.

PECTORALIS FLAP

Appraise

1. This is a versatile flap for reconstruction following excision of tumours in the head and neck region. It will reach the pharynx, the lower cheek, the neck and shoulder and will just reach the floor and lateral walls of the oral cavity as well as the area of the pinna.

2. It is a myocutaneous flap based on the pectoral vessels supplying the pectoralis major muscle. These in turn supply skin overlying the muscle.

3. Its most useful application is for intraoral reconstruction, where an island or paddle of skin the size of the defect is transferred from the lower chest wall on the distal part of the flap. The muscle is transposed subcutaneously with this island of skin and protects the carotid vessels when a block dissection has been carried out. The donor site can be closed primarily.

4. Web contractures may develop in the neck postoperatively when the flap is used in the anterior part of the oral cavity.

Action

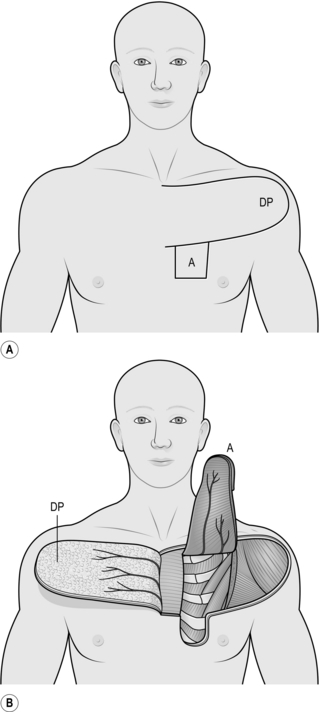

2. Measure the size of the defect.

3. Measure and mark an appropriate area of skin overlying the distal inferior portion of the pectoralis major muscle just above the costal margin (Fig. 33.20). Do not include skin across the midline or skin more than 2 cm below the lower margin of the pectoralis muscle.

4. Mark out a deltopectoral flap (see above) above the skin paddle.

5. Elevate the deltopectoral flap medially; you can omit this step if you are experienced, by passing the pectoralis flap under the deltopectoral flap.

6. Identify the lateral margin of the pectoralis muscle and elevate its border.

7. Dissect this distally to the sternal attachment, freeing the muscle from its attachments to the chest wall.

8. Dissect the distal element free from the midline.

9. Elevate the muscle with its attached skin island up to the clavicle. In doing this, look for and protect the two vascular pedicles on the undersurface.

10. Divide the attachment of the muscle to the humerus at the margin of the deltoid muscle.

11. Pass the flap subcutaneously beneath the neck skin if a block dissection has been carried out and pass the island of skin into the defect. Some rotation of the muscle pedicle may be necessary. Make sure the flap sits comfortably in place, and suture the skin paddle into the defect.

12. Suture the edges of the muscle to adjacent tissue to support it when the patient sits up.

13. If neck skin has been incised or excised to accommodate the muscle pedicle, take a split skin graft and apply this to the exposed muscle.

14. Close the donor defect primarily. This may require wide undermining to allow approximation of the skin edges.

LATISSIMUS DORSI FLAP

Appraise

1. The most useful application of this flap is as a myocutaneous flap in breast reconstruction and reconstruction of chest wall defects. It can be used in pharyngeal reconstruction and for defects of the back up to and just above the nape of the neck.

2. It can be used as a muscle flap alone to cover a large defect, or the muscle can be used to transfer a small island of skin, as in breast reconstruction, or a large island of skin. If a large island is transferred, primary closure of the donor site is not possible.

3. The flap has wide application in free tissue transfer (see below).

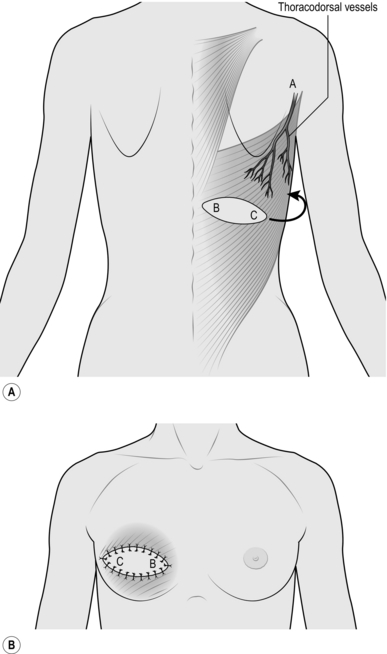

4. The flap is based on the thoracodorsal vessels, and these enter the muscle just below its insertion into the humerus.

Action

1. For an anterior chest wall defect, lay the patient on the table in the lateral position.

2. Create and measure the defect on the anterior chest wall.

3. Mark out the island of skin on the back overlying the latissimus dorsi muscle appropriate to the defect (Fig. 33.21).

4. Check that the island will reach the defect, using a tape based in the region of the vascular hilum at the lower margin of the posterior axillary fold. Remember, the most posterior point of the flap has to reach the most anterior point of the defect.

5. Incise the skin along the marked lines around the island down to the muscle.

6. Dissect the skin and fascia off the upper surface of the whole muscle proximal and distal to the skin paddle.

7. Identify the anterior border of the muscle.

8. Separate the muscle from the underlying serratus muscles and ribs.

9. Divide the muscle from its attachment, distally and posteriorly.

10. Separate the muscle up to its pedicle, identifying and preserving the principal vessels on the underlying surface.

11. Dissect gently at the hilum to avoid damaging the principal vessels.

12. Identify the vessels to the serratus anterior muscle arising from the thoracodorsal vessels, and divide them.

13. Develop a subcutaneous tunnel between the defect of the flap and the anterior chest wall defect.

14. Pass the flap subcutaneously through this tunnel into the anterior wall defect.

15. Close the donor site defect primarily, if possible, even if this means extensive undermining. Insert a large suction drain.

16. Change the patient to the supine position, re-towelling if necessary.

17. Undermine the skin edges of the defect where appropriate.

18. Suture the latissimus dorsi muscle to the chest wall.

19. If this is a breast reconstruction, insert a prosthesis beneath the latissimus dorsi muscle.

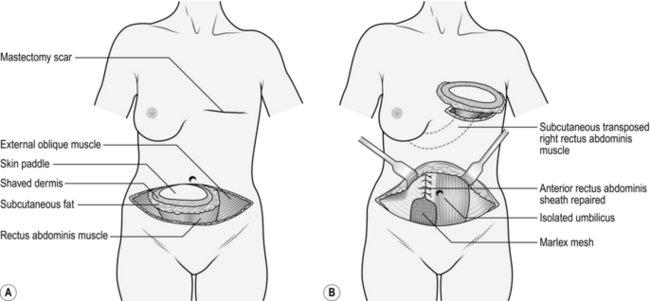

TRAM FLAP

Appraise

1. The transverse rectus abdominis muscle (TRAM) provides an alternative flap for breast reconstruction to the latissimus dorsi muscle. It has the advantage that it can normally transfer sufficient autologous tissue to avoid the necessity of using an implant.

2. The flap can also be used for reconstructing chest wall defects and defects of the perineum. In either of these circumstances the skin paddle may be taken in the vertical plane (a vertical rectus abdominis muscle or VRAM flap), with the skin paddle lying completely over the muscle.

3. The flap may be used as a pedicled flap based either on the superior deep epigastric vessels for breast reconstruction or chest wall defects, or on the inferior deep epigastric vessels for perineal defects.

4. When used as a free flap, most commonly for breast reconstruction, prefer to use the inferior deep epigastric vessels, which are larger and more reliable. These vessels can be dissected through the muscle, avoiding harvesting of the muscle to raise a deep inferior epigastric perforator (DIEP) flap.

5. The abdominal skin wound closure is similar to that of an abdominoplasty (see below).

Action

1. Mark the patient preoperatively in the standing position.

2. For breast reconstruction plan to excise the mastectomy scar if possible.

3. Avoid large skin flaps if the patient has been treated by radiotherapy.

4. Mark the midline and edges of the rectus abdominis muscles.

5. Plan and mark the skin island to be transferred centrally over the contralateral muscle just below the level of the umbilicus. If you are an experienced surgeon, you will centre the flap in the midline.

6. Mark a symmetrical ellipse to be excised that includes the planned skin island of the flap.

7. In the operating theatre, excise the mastectomy scar and raise the adjacent skin flaps to accommodate the flap.

8. Shave the epidermis off the skin adjacent to the planned skin island but within the marked outer ellipse. The residual dermis protects the subdermal pedicle, which in turn contributes to the viability of the subcutaneous flap beyond the boundaries of the skin paddle. Excise the residual skin of the symmetrical ellipse, the skin paddle and the subcutaneous fat (Fig. 33.22).

9. Cut through the deep fascia around the base of the subcutaneous fat to be included on the flap. Include in this the perforating vessels close to the midline both below and just above the umbilicus.

10. Gently pass your finger around the rectus abdominis muscle distal to the flap until the whole muscle is isolated. Cut through it with a cutting diathermy, identifying and ligating the inferior epigastric vessels when you encounter them on the undersurface.

11. Cut vertically through the middle of the anterior sheath of the muscle superiorly.

12. Elevate the muscle with the overlying subcutaneous fat and skin up to the costal margin.

13. Create a subcutaneous tunnel from the abdominal wall cavity through to the mastectomy wound and pass the skin paddle through this.

14. Orientate the skin paddle and fat and tack the base into place, checking there is no tension on the pedicle.

15. Suture the flap into place in layers and insert a Redivac drain.

16. Close the donor defect by suturing the upper part of the anterior rectus sheath first with a continuous 1 polypropylene suture.

17. Repair the residual defect in the anterior sheath with Marlex mesh sutured firmly in place with a continuous 1 polypropylene suture.

18. Close the abdominal wall in layers, transposing the umbilicus to its new site as appropriate. Insert two Redivac drains.

19. Support the abdomen with a pressure garment and lightly dress the breast wounds.

20. Remove the drains when the drainage has diminished and remove the sutures at 3 weeks.

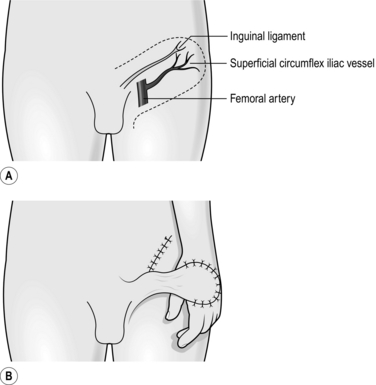

GROIN FLAP

Action

1. Create the defect on the hand.

2. Identify the femoral artery by palpation.

3. Mark a point over this 2 cm beneath the inguinal ligament.

4. Draw a line from this point to the anterior superior iliac spine, which acts as the axis of the flap.

5. Mark an area over the iliac crest close to the mid-axillary line, which is to be used for the definitive skin cover.

6. Mark the flap to include this with parallel lines on either side of the central axis at an equal distance from it (Fig. 33.23).

7. First incise the skin laterally down to the deep fascia and include the fascia with the flap.

9. At the edge of the sartorius muscle include the fascia, overlaying it with the flap, and so ensure that the superficial circumflex vessels are retained within the flap.

10. Dissect the flap free to within 3 cm of the femoral vessels.

11. Check that the defect on the hand will accommodate the flap.

12. Close the donor defect primarily up to the pedicle of the flap, if necessary flexing the knee and hip.

13. Tube the portion of the flap that will bridge the gap between groin and hand by suturing the two skin edges together.

14. Suture the distal part of the flap into the defect.

15. Immobilize the limb against the trunk after placing padding between the limb and the trunk.

16. Perform a delay procedure at 2 weeks by incising half of the skin at the base of the pedicle opposite the suture line.

17. Identify the axial vessels; ligate and divide them.

19. Three weeks after the initial procedure, divide the pedicle completely at its base and in-set it into the groin wound.

20. In-set the flap into the hand defect with a few sutures. If tension is apparent in the skin, do not suture it at all, but cover the exposed part of the flap with a paraffin gauze dressing.

21. Insert the flap 2 days later.

22. Thin the flap 3 months later, if necessary, by excising the subcutaneous tissue in stages.

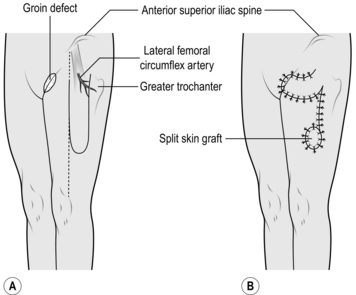

TENSOR FASCIA LATA FLAP

Appraise

1. This flap is useful in treating trochanteric pressure sores and defects of the groin, particularly when the femoral vessels are exposed.

2. It can also be used for ischial pressure sores and defects of the upper thigh and lower abdominal wall.

3. It is a myofasciocutaneous flap and is based on the vessels to the tensor fascia lata muscle.

4. Inclusion of the lateral cutaneous nerve of the thigh within the flap allows it to be used as a sensory flap.

Action

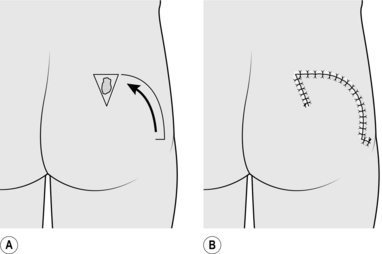

1. Place the patient supine on the table, rotate the pelvis through 30 degrees and support this and the leg on the side of the defect.

2. Create and measure the defect in the groin.

3. Identify the site of entry into the muscle of its vascular pedicle, the transverse branch of the lateral femoral circumflex artery. This point is 8 cm distal and just lateral to the anterior superior iliac spine.

4. Keep this point in the base of the flap.

5. Draw a line from the anterior superior iliac spine to the lateral margin of the patella and use this as the anterior margin of the flap.

6. Mark the posterior margin of the flap using a width of 6–10 cm (Fig. 33.24).

7. Mark the distal extremity of the flap so that it is not more than two-thirds of the length of the thigh. Check that the flap will reach the defect.

8. Incise the skin distally down to the deep fascia.

9. Incise the skin on the anterior and posterior margins and elevate the flap together with the fascia lata.

10. As the flap is reflected proximally, the tensor fascia lata muscle comes into view. If necessary, divide any small distal vascular pedicle into the muscle after first identifying the large vascular pedicle proximally.

11. Check that the flap will rotate into the defect.

12. Incise the skin between the flap and the defect, and undermine it on either side, allowing the flap to lie in this defect.

13. Excise any excess thigh skin to allow the flap to sit comfortably.

14. Suture the flap into place.

15. Close the donor defect primarily as far as possible.

16. Take a skin graft from the opposite thigh and apply it to the residual flap donor defect.

17. Dress the graft and its donor site with paraffin gauze, dressing gauze, cotton wool and crepe bandage.

18. Leave the flap exposed and nurse the patient on his contralateral side.

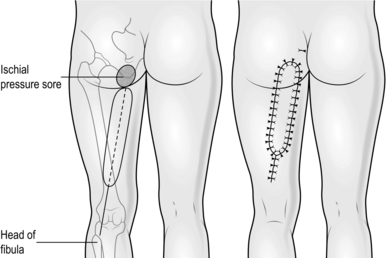

BICEPS FEMORIS FLAP

Appraise

1. This flap is particularly useful for ischial pressure sores.

2. It is a myocutaneous flap but can be used as a simple muscle flap.

3. The biceps femoris muscle receives a segmental blood supply from several vessels which are branches of the profunda femoris artery. In order to preserve all these vessels the flap is transferred as an advancement flap.

4. An advantage of this flap is that it can be advanced more than once.

Action

1. Place the patient prone on the table.

2. Create the defect by excising the whole lining to the ischial pressure sore cavity. With an osteotome reduce the prominence of the ischial tuberosity.

3. Draw a line from the ischial tuberosity to the head of the fibula. Use this as the axis of the flap and mark an elliptiform flap, 8–10 cm broad around this, extending proximally to the defect and distally to within 5 cm of the crease of the knee joint (Fig. 33.25).

4. Incise along the lines down to the margins of the biceps femoris muscle.

5. Divide the origins of the biceps femoris, semitendinosus and semimembranosus muscles at the ischial tuberosity.

6. Divide the biceps femoris tendon at the distal margin of the flap. Divide the semimembranosus and semitendinosus distally if necessary to provide greater mobility of the flap.

7. Advance the flap into the defect and suture the muscle to obliterate the dead space.

8. Suture the skin of the flap into the skin defect after inserting a large suction drain.

9. Suture the distal portion of the flap defect primarily and apply minimal dressings.

GASTROCNEMIUS FLAP

Appraise

1. Both heads of the gastrocnemius muscle can be used separately for covering defects on the anterior aspect of the leg.

2. They can be used as simple muscle flaps or as myocutaneous flaps.

3. The flaps are used for covering exposed bone in the upper third of the tibia and for covering the exposed knee joint, sometimes even in the presence of a metal prosthesis.

4. The muscle flap alone is more malleable and versatile than a myocutaneous flap.

5. Although the lateral head is slightly longer, use the nearest muscle head to the defect. Do not use both heads simultaneously.

Action

1. Place the patient in the lateral position, with the affected leg uppermost.

2. Mark out and create the defect.

3. Make a vertical incision through skin and subcutaneous tissue down the midline of the calf, posteriorly.

4. Identify the muscle bellies of gastrocnemius and their relevant attachments to the tendo calcaneus (Fig. 33.26).

5. Separate the fascia overlying the respective belly of the muscle to be used.

6. Incise the tendon just distal to the muscle attachment.

7. Elevate the muscle belly proximally by dissecting laterally and medially, dividing its attachment to the opposite belly.

8. Free the muscle belly to the level of the popliteal fossa, preserving the vascular pedicle passing into it.

9. Create a subcutaneous tunnel from the base of the muscle belly to the defect and enlarge to accommodate the muscle flap.

10. Pass the muscle belly through this tunnel into the defect.

11. Suture the muscle to the edges of the defect.

12. Close the donor defect in layers and insert a suction drain.

13. Take a thick split skin graft from the thigh and apply it to the exposed muscle in the defect.

14. Splint the leg for 10 days.

15. Allow weight-bearing at 10 days and mobilize progressively. Fit an elastic support stocking to cover the graft overlying the muscle. This should be worn for 3 months.

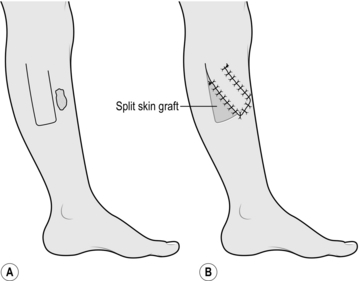

FASCIOCUTANEOUS FLAP

Appraise

1. These flaps have their greatest use in providing skin cover to exposed bone in the middle third of the leg.

2. When based proximally, they may not be true axial pattern flaps but depend on preserving the rich vascular network lying superficial to the deep fascia.

3. You may use flaps with a 3:1 or more length-to-breadth ratio.

4. With intimate knowledge of the anatomy of the vessels which perforate the deep fascia, long flaps based distally can be designed and may be useful in covering the exposed distal third of the tibia.

Action

1. Mark out and create the defect.

2. Mark out the flap based proximally with a 2:1 ratio.

3. Check that the flap will reach the defect when transposed (Fig. 33.27).

4. Incise the flap distally, passing through skin, subcutaneous tissue and deep fascia.

5. Elevate the flap proximally, incising along the lateral margins and preserving the deep fascia with the flap.

6. Transpose the flap into the defect.

7. Suture the flap into the defect in layers.

8. Take a split graft from the opposite thigh.

9. Apply the split skin graft to the flap donor defect. Dress with paraffin gauze and dressing gauze and retain with tie-over sutures.

TISSUE EXPANSION

Appraise

1. The principle of tissue expansion is exemplified by the stretched abdominal wall resulting from pregnancy.

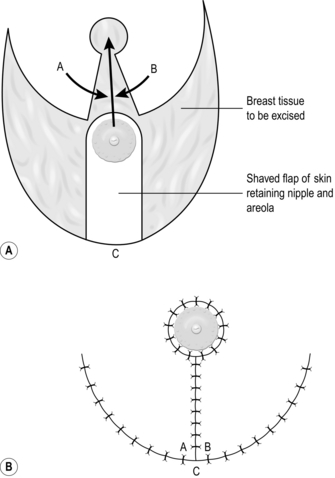

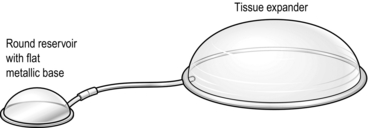

2. A tissue expander (Fig. 33.28) is inserted beneath the deep fascia or superficial muscle and expanded serially by injections of saline into an attached reservoir to stretch the overlying skin.

Fig. 33.28 Tissue expander and reservoir.

3. Following expansion, the expander is removed and the surplus skin used to cover the adjacent defect.

4. Expanders are most effective when placed on a bone base. They are particularly effective when placed on the calvaria (Latin: = skull) to expand scalp, and on the chest wall to expand skin for breast reconstruction. They have limited value in limbs.

5. There are some more sophisticated tissue expanders available specifically designed for breast reconstruction. Some of these have a double lumen, one of which is filled with silicone. Others have a reservoir that can be detached from a valve linking it to the expander, allowing the expander to be left in situ.

Action

1. Identify an area of normal skin to be expanded which is adjacent to the defect.

2. Choose an appropriate tissue expander whose base will lie within the boundaries defined.

3. Make an incision beyond the chosen area in a radial direction.

4. Attach the reservoir to the expander and insert saline. Remove air from the system and check its patency.

5. Make an appropriate pocket for the expander and insert it. This pocket should be submuscular or subfascial, but may be subcutaneous.

6. Make a separate pocket for the reservoir in a suitable accessible adjacent subcutaneous area and insert it.

7. Recheck the patency of the system and close the wound.

8. Serially inject saline into the reservoir as an outpatient procedure.

9. When sufficient expansion or more has been achieved, re-admit the patient for the second stage.

10. Remove the expander and stretch the expanded skin over the defect.

GRAFTS OF OTHER TISSUES

NOSE

1. Composite defects of skin and cartilage at the nostril margin can be reconstructed using composite grafts from the ear, as described under composite skin grafts (see above).

2. Most other small cartilaginous defects of the nose can be reconstructed using cartilage from other parts of the nose during a corrective rhinoplasty.

3. If there is extensive cartilaginous loss and the nasal tip requires support, take an L-shaped bone graft from the iliac crest and insert it through a midcolumellar incision.

4. More sophisticated techniques include the insertion of homo-graft cartilage (see below) or calvarial bone graft inserted from above after reflecting a bicoronal scalp flap.

EYELIDS

1. You rarely need to provide cartilage support for the upper eyelid.

2. Large defects of the lower eyelid often require the introduction of cartilage for support and the best donor site for this is the septum of the nose. This provides a composite graft of cartilage and mucous membrane. The latter is used to reconstruct the conjunctival surface.

Action

1. Create the defect and measure it.

2. Mark an appropriate area of the septum using a nasal speculum, commencing at least 3 mm behind the anterior limit of the septum.

3. Infiltrate the marked area with 0.5% lidocaine and 1:200 000 adrenaline (epinephrine).

4. Infiltrate the septum on the opposite side with the same preparation.

5. After allowing at least 7 minutes for the adrenaline (epinephrine) to take effect, incise the mucosa, passing through this and the underlying cartilage but avoid penetrating the nasal mucosa on the contralateral side.

6. Separate the contralateral nasal mucosa from the cartilage using a mucosal elevator.

7. Cut around the full margin of the graft and remove it.

8. Stop the bleeding with pressure for 5 minutes timed by the clock.

9. Insert the graft into the defect and stabilize it with an absorbable suture through the cartilage at each margin.

10. Suture the conjunctival surface with 6/0 absorbable suture.

EAR

1. Costal cartilage is used for total ear reconstruction.

2. Reconstruction of a major portion of the ear may be difficult. It is sometimes justifiable to discard those cartilaginous segments already present and perform a total ear reconstruction.

3. If there is inadequate skin available, you must employ preoperative tissue expansion (see above) or use a temporoparietal flap.

Action

1. Measure the normal ear and make a template for the new ear.

2. Make a straight, oblique incision over the medial end of the seventh and eighth costal cartilages.

3. Retract the skin and subcutaneous tissue and expose an area of cartilage equivalent to the size and shape of the ear.

4. Mark out an outline of cartilage from the template using the seventh and eighth costal cartilages and excise this.

5. Close the donor defect in layers.

6. Place the graft on a wooden board on a table and carefully shape the cartilage, creating a well-defined helical rim and an antihelical fold.

7. Make an incision along the hairline of the posterior margin of the auricular skin where it meets hair-bearing scalp skin.

8. Create a subcutaneous pocket beneath the auricular skin to accommodate the cartilage graft.

9. Insert the graft and close the skin.

10. Insert sutures through the skin in the region of the scaphoid fossa and concha, to highlight the contour of the grafts.

11. After 6 months, reflect forwards the cartilage graft together with the underlying subcutaneous tissue and insert a split skin graft on to the posterior surface of the reconstructed ear and the postauricular region to create a postauricular sulcus.

VASCULAR GRAFTS

Appraise

1. Large vascular grafts are described in Chapter 23. Employ small-vessel grafts for replanting and free-flap transfer. They are occasionally used when limb vessels have been injured.

2. Vein grafts are used to replace both damaged arteries and veins.

3. Choose a vein graft that matches the vessel that has been destroyed.

4. Use magnification for the repair and a microscope when repairing grafts under 2 mm in diameter.

Action

1. Identify the length of vessel that has been damaged.

2. Place an appropriate size clamp on normal vessel on either side of the damaged section and resect this damaged section.

3. Inspect the cut ends under magnification and check that the endothelium is normal. If it is not, resect further.

4. Check that there is good flow of blood from the cut proximal arterial stump, or the cut distal venous stump, by holding the adventitia of the vessel with jeweller’s forceps, and temporarily releasing the clamp.

5. Select a superficial vein of appropriate size and length for insertion as a graft into the defect. For vessels greater than 2 mm diameter, use the long saphenous vein, which is the best available vein graft for both arteries and veins. For vessels smaller than this, use veins from the dorsum of the foot or from the flexor aspect of the forearm.

6. Make an incision through the skin directly over the full length of the chosen vein.

7. By blunt dissection, isolate the full length of the vein to be used.

8. Ligate all branches of the vein graft or use the bipolar coagulator to seal minute branches. Do not use unipolar diathermy, which will damage the graft.

9. Isolate a segment of vein graft longer than that required. Ligate and divide the vessel proximally and distally.

10. Remove the graft and irrigate it gently with warm heparinized Hartmann’s solution or saline to exclude leaks.

11. Place the graft in the site of the defect, ensuring that the blood flow in the graft will be in the usual direction.

12. Choose an appropriate double clamp. Place one portion of this clamp on the proximal end of the divided normal vessel and the other on the vein graft.

13. Under magnification, clean the adventitia from the vessel walls of both stumps using small scissors.

14. Flush the stumps with heparinized Hartmann’s solution, being careful not to grasp the endothelium with forceps.

15. Dilate the vessel with vessel dilators and approximate the ends.

16. Suture the anterior wall with interrupted 8/0 or 10/0 nylon sutures. Turn the clamp over and suture the opposite wall.

17. Before inserting the final two sutures, check that the anastomosis is patent.

18. Carry out a similar anastomosis at the distal end, checking that the graft has been stretched to its original length and that there is no torsion.

19. Remove the distal clamps first and then remove the proximal clamps.

20. If there is small leak at either anastomosis, cover it with a warm swab but do not occlude the vessel.

21. If there is a gross leak, reapply a single clamp to obstruct the flow and insert extra sutures. Remove the clamp and observe.

22. If flow is not established, resect the anastomosis and repeat.

OTHER GRAFTS

1. Nerve grafts, tendon grafts and bone grafts are described in Chapter 30.

2. Homograft (Greek: homos = same; from the same species) bone, xenograft (Greek: xenos = strange, foreign; from a different species) cartilage and xenograft collagen are all used, after appropriate preparation, in reconstruction. Theoretically, they act as a scaffold into which the patient’s own tissue grows. The benefit with xenograft cartilage and xenograft collagen may be only temporary as the graft tends to be absorbed.

3. Homograft and xenograft skin may be used as temporary biological dressings in burns, but they are eventually rejected.

MICROVASCULAR SURGERY

1. Microvascular surgery involves the anastomosis and repair of small vessels.

2. It has clinical application in cases of re-plantation and free tissue transfer.

3. The surgery is highly specialized. Operations may take many hours and require special instruments in addition to an appropriate microscope.

4. This type of operation should be carried out only in specialized units.

REPLANTATION

Action

1. Control bleeding from the amputation stump by simple pressure and elevation.

2. Avoid clamping vessels to stop haemorrhage unless essential, as this may cause unnecessary damage.

3. Contact the nearest microvascular surgery unit and take advice.

4. Prepare the patient and amputated part for urgent transfer.

MACROREPLANTATION

Appraise

1. The force required to sever a major portion of a limb is considerable and patients who have suffered such an injury may have other injuries to their body which may take priority in treatment.

2. Criteria for attempting re-plantation are:

The patient should be relatively fit

The patient should be relatively fit

The amputated portion should not be too severely damaged

The amputated portion should not be too severely damaged

The ‘warm ischaemic time’ of the amputated part should not exceed 6 hours. Muscle is unlikely to recover after this period and if it is revascularized it could infuse a fatal dose of nephrotoxic substances, including myoglobin, into the circulation

The ‘warm ischaemic time’ of the amputated part should not exceed 6 hours. Muscle is unlikely to recover after this period and if it is revascularized it could infuse a fatal dose of nephrotoxic substances, including myoglobin, into the circulation

There should be a reasonable prospect of some functional recovery.

There should be a reasonable prospect of some functional recovery.

Action

1. Debride and clean both the proximal stump and the wound of the amputated part.

2. Shorten the skeletal structures and fix these. This should allow primary anastomosis of vessels and nerves.

3. Revascularize the amputated part by anastomosing the appropriate artery, or arteries, using vein grafts if necessary.

4. If the warm ischaemic time has been relatively long, revascularize the part prior to skeletal fixation. Allow perfusion of the amputated part for several minutes, discarding the venous blood. Transfuse the patient appropriately. Revise the anastomoses after skeletal fixation if necessary.

5. Anastomose twice the number of veins as the number of arteries repaired, again using vein grafts if necessary.

6. Repair the tendons and muscles.

8. Carry out extensive fasciotomies, incising through skin, subcutaneous tissue and deep fascia on the proximal stump and on the amputated part.

9. Harvest a split skin graft and apply this to the fasciotomy sites and any other residual raw areas where there has been skin loss.

10. Monitor the limb carefully postoperatively, and be prepared to return the patient to theatre at any time if there is doubt about viability of the replanted or revascularized part.

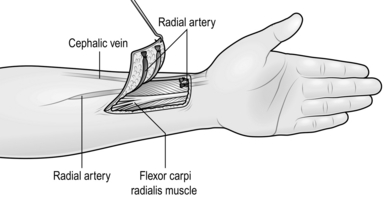

FREE TISSUE TRANSFER

Appraise

1. Free tissue transfer is used in many forms of reconstruction. It consists of transferring tissue from one part of the body to another.

2. Isolate the tissue on a recognized vascular pedicle and, after transfer to its distant site, anastomose the vessels of the vascular pedicle to appropriate nearby vessels, either directly or with vein grafts.

3. The arterial supply to the tissue is usually established with an end-to-side anastomosis to an adjacent artery, so that the distal flow of this artery is not terminated.

4. The venous drainage of the tissue is usually established via end-to-end anastomoses to superficial veins or to venae comitantes of a nearby artery. Occasionally, if the venous drainage is inadequate, you can apply leeches to the compromised tissue temporarily until adequate venous drainage is established.

5. Most free flaps currently used in reconstruction consist of cutaneous or myocutaneous flaps. Apart from the flaps described above there are many other cutaneous and myocutaneous flaps which are occasionally used.

6. Other free tissue transfers include the following:

Vascularized bone grafts from rib, iliac crest, fibula, radius and metatarsal