Chapter 40 Pituitary Tumors

Diagnosis and Management

• Pituitary tumors present in various ways as a result of excess or deficient secretion of pituitary hormones or extrinsic compression on the pituitary stalk or adjacent structures. Approximately 75% of pituitary adenomas are functioning tumors; of these, half are prolactinomas, less than 25% secrete growth hormone (GH), and the rest secrete adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), or thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH).

• Functioning tumors often present with symptoms due to hormone hypersecretion, and nonfunctioning tumors generally present with symptoms due to mass effect.

• Transsphenoidal adenomectomy (TSA) is the first line of treatment for nonfunctioning tumors. Medical therapy is the first line of treatment for prolactinomas. Other functioning adenomas generally require surgical resection, medical treatment, or radiation therapy. Surgery through the microscopic, extended transsphenoidal, or endoscopic route is safe and effective in experienced hands. Craniotomy may be required for a tumor extending beyond the sellar region.

• Patients with functioning pituitary adenomas require long-term follow-up to assess clinical and laboratory parameters. This is best done at a center that can provide a neurosurgeon, an endocrinologist, a radiation oncologist, and an ophthalmologist. Pituitary hormones should be regularly followed in all these patients; patients with residual tumor after treatment should be monitored with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, and patients with optic nerve compression require periodic formal visual field testing.

The Pituitary Gland

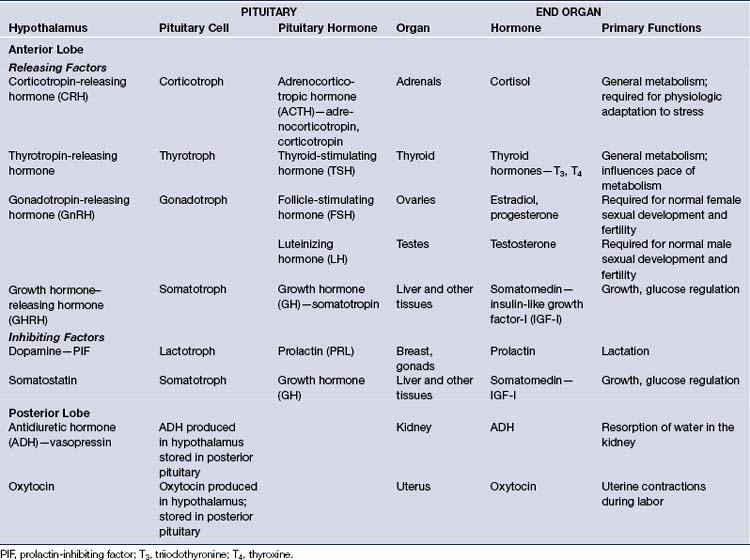

The pituitary gland regulates the function of numerous other glands, including the thyroid, adrenals, ovaries, and testes. It controls linear growth, lactation, and uterine contractions in labor, and it manages osmolality and intravascular fluid volume via resorption of water in the kidneys. It secretes eight peptide hormones, six from the anterior lobe and two from the posterior lobe (Table 40.1).

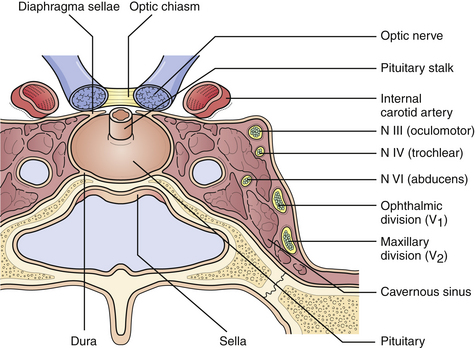

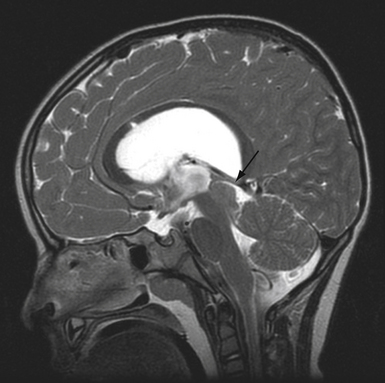

The pituitary lies in the sella turcica, a saddle-shaped concavity in the sphenoid bone. Its stalk, which contains the pituitary portal veins and neuronal processes, passes through the diaphragma sella, just above which pass the optic nerves (Fig. 40.1). The cavernous venous sinuses form the lateral borders of the sella, and contain within them the internal carotid arteries, cranial nerves III, IV, and VI, and the ophthalmic and maxillary divisions of cranial nerve V.

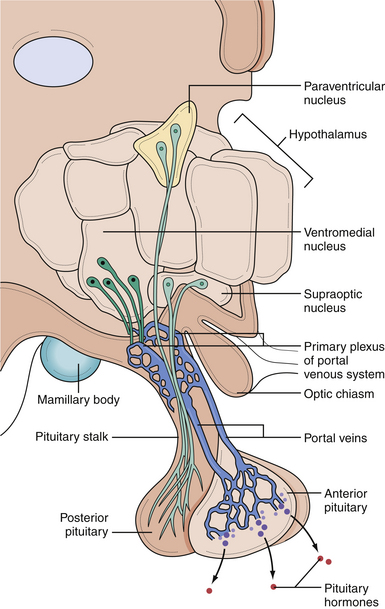

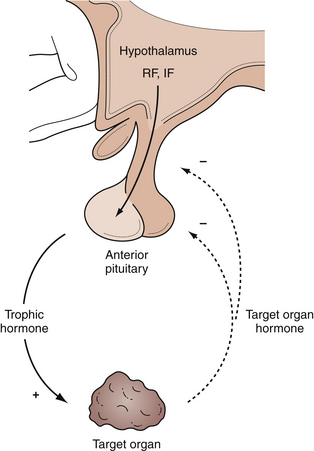

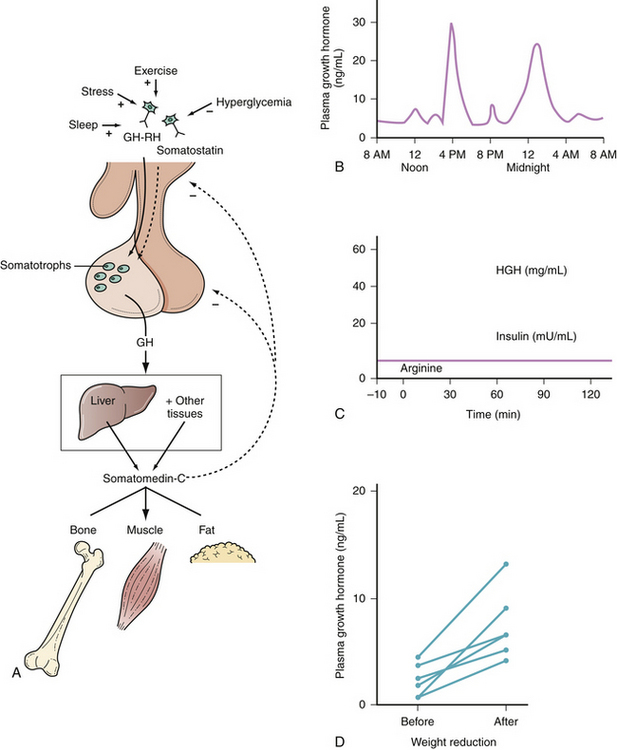

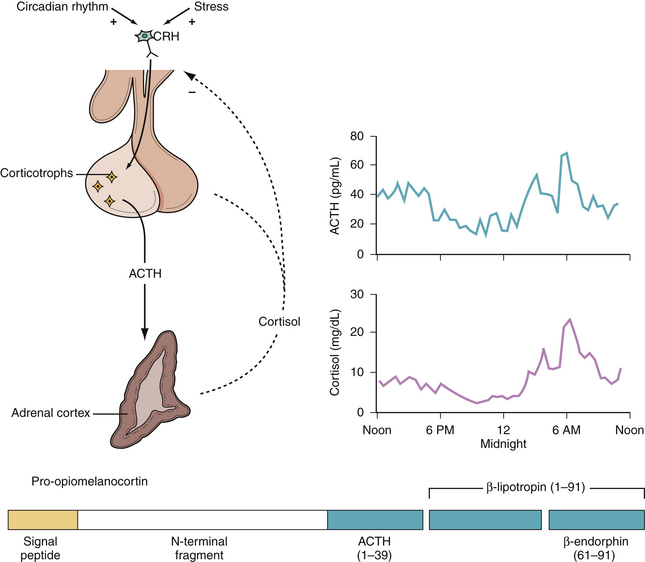

In the anterior lobe of the pituitary gland, known as the adenohypophysis, five distinct types of cells produce and secrete six different hormones. Lactotroph cells make prolactin (PRL), somatotroph cells produce growth hormone (GH), corticotrophs secrete adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), thyrotrophs make thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), and gonadotrophs produce follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH). The secretion of these hormones is regulated by the hypothalamus and by inhibitory feedback control by target organ hormone products (Figs. 40.2 and 40.3).

The hypothalamus secretes releasing factors to stimulate the production of pituitary hormones. Corticotropin-releasing factor (CRH), thyrotropin-releasing factor (TRH), and gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) positively regulate the production of ACTH, TSH, and the gonadotropins, LH and FSH. GH secretion is more complicated in that it receives both positive and negative hypothalamic manipulation, via GH-releasing hormone (GHRH) and somatostatin, respectively. Prolactin secretion is primarily inhibited by the hypothalamic release of dopamine, also known as prolactin-inhibiting factor. Some of these hypothalamic factors influence the production of more than one anterior pituitary hormone. For instance, TRH, which primarily stimulates TSH production, also has a positive effect on prolactin release.

Epidemiology

Pituitary adenomas have an annual incidence of 25 per 1 million people and account for nearly 10% of all surgically resected brain tumors, with nonfunctioning adenomas and prolactinomas being the most common pituitary tumors.1,2 Many of these tumors are subclinical and may never present during a patient’s lifetime; autopsy studies show an 11% to 27% incidence of occult microadenomas.3–6 Pituitary tumors are the third most common primary intracranial neoplasm, behind glioma and meningioma,7 and are more common among African Americans, in whom they account for more than 20% of central nervous system neoplasms.8

Microadenomas are most often found in women of childbearing age. Though studies in the 1970s appeared to demonstrate a higher incidence of adenomas among women than men, it is unclear if there is actually a higher prevalence among women or if the effect of a tumor on pituitary function and, therefore, reproduction leads to a higher rate of detection. Autopsy studies show no sex predominance.2 Men with pituitary tumors more often present with macroadenomas in their fifth and sixth decades of life.3

Classification

The major classifications of pituitary tumors are based on their size, secretory abilities, and histological type. Tumors with a diameter of less than 10 mm are microadenomas, and those greater than 10 mm are macroadenomas. Tumors greater than 4 cm are considered giant adenomas.

Functioning adenomas are generally classified by the hormones they secrete. Any of the multiple cell types within the pituitary can lead to a functioning pituitary tumor. Functioning tumors may secrete PRL, GH, ACTH, FSH, LH, or TSH. Nonfunctioning tumors do not secrete clinically relevant levels of hormone. However, even among nonfunctioning tumors, multiple different tumor types are found, including null cell, oncocytoma, silent gonadotropin or glycopeptide-secreting, silent corticotropin-secreting, and silent somatotropin-secreting.9

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), tumors with benign histological features are typical pituitary adenomas, but rare invasive tumors with an increased rate of mitosis and extensive p53 nuclear reactivity are classified as atypical adenomas. Pituitary carcinoma is very rare, constituting less than 0.2% of pituitary tumors, and the diagnosis is made only when distant metastases are found.10,11

Nonfunctioning Pituitary Adenomas

Nonfunctioning adenomas account for 30% of pituitary tumors.12 The term nonfunctioning reflects the fact that these tumors do not cause clinical hormone hypersecretion and so do not cause hypersecretory syndromes.13 These tumors are heterogeneous with multiple histopathological cell types. Though they do not cause signs of clinical hormone hypersecretion, histopathological evidence of hormone expression is evident in more than 40%.

Presentation

Nonfunctioning adenomas are benign lesions that are typically large upon presentation and manifest with symptoms of mass effect.14 Pressure on the pituitary gland can lead to decreased pituitary function, and nearly one third of these patients have hypopituitarism.15 Gonadotropins are generally the first hormones affected, then GH, followed by TSH and ACTH. Hormone dysfunction may lead to amenorrhea or hypogonadism and decreased libido, or to hypothyroidism with weight gain, depression, fatigue, and mental slowing. These changes develop insidiously as the tumor grows, so the patient may be unaware until the lesion is large.

Diagnosis

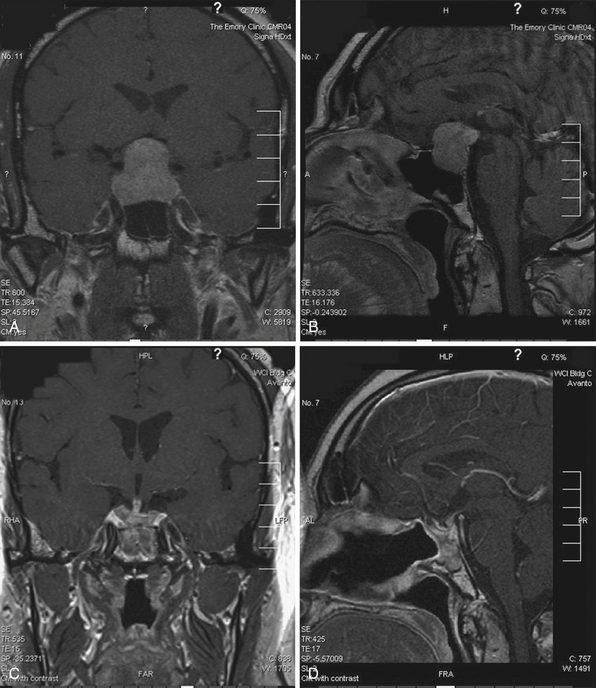

Plain radiographs may demonstrate an enlarged, round sella, and the sellar floor may appear doubled due to a thinned, asymmetrically worn lamina dura. High-resolution magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with cuts through the sellar region is essential for surgical planning, as it will show the precise size and location of the lesion as well as its relationship with the chiasm, cavernous sinus, and other surrounding structures (Fig. 40.4), and a computed tomography (CT) scan will demonstrate the sphenoid sinus anatomy.

Treatment Options

Surgery

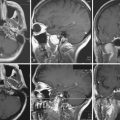

The first line of treatment for a nonfunctioning pituitary adenoma is transsphenoidal resection of the tumor, which provides immediate relief of mass effect and has a low rate of complications.16–19 This surgery is generally done as an elective procedure. An extended transsphenoidal approach may be needed when the tumor has reached beyond the sella and a transcranial approach or combined transsphenoidal-transcranial approach may be considered if there is significant supratentorial tumor extension.20,21

The goals of surgery are to eliminate mass effect from the pituitary and surrounding structures, to preserve or restore pituitary and visual function, to resect enough of the lesion to prevent recurrence, and to obtain tissue for histopathological analysis.22

Hermann Schloffer performed the first transsphenoidal resection of a pituitary tumor in 1907 and Harvey Cushing popularized it in the two decades afterward.23,24 Neurosurgeons have been trying to perfect the transsphenoidal adenomectomy (TSA) since. The standard methods in use today involve either an endonasal or sublabial approach to the sella.

Endonasal Transsphenoidal Approach

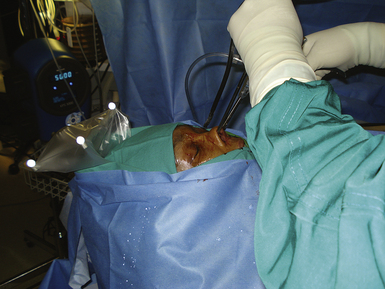

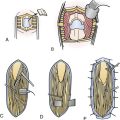

In the endonasal transsphenoidal approach, the patient’s head is placed in a Mayfield cranial fixation clamp. The body is placed supine with the neck somewhat extended and the head turned slightly toward the right to face the surgeon, permitting a good view through the nares (Fig. 40.5).

The operating microscope is brought into the field and the sphenoid sinus is opened with an osteotome and Kerrison rongeur. The opening is enlarged to allow visualization of the lateral portion of the sella. Some surgeons then obtain fluoroscopic or image-guided confirmation of the sella’s position; however, direct visualization is generally sufficient.

Endoscopy

The lesion is removed in the same manner as with the microscopic approach. The endoscope provides a wide field of view and angled scopes permit enhanced inspection of the walls of the sella, as well as the suprasellar, retrosellar, and parasellar regions to search for residual tumor. Three-dimensional endoscopes have been introduced recently and permit a more realistic, nondistorted view of the regional anatomy than do the conventional two-dimensional endoscopes (Fig. 40.6).

After the lesion is removed, DuraForm is placed over the sella. Gelfoam is used to pack the sphenoid sinus, and NasoPore is laid over the bilateral sphenoethmoid recesses. If a CSF leak is present, a mucosal septal flap may be used to assist in closure. A speculum is not needed with this approach.25,26

Sublabial Transsphenoidal Approach

Pediatric patients with small nares or patients with large tumors may be treated via a sublabial TSA. The patient’s upper lip is retracted and a horizontal incision is made in the gingival mucosa. A pathway is followed to the maxilla and floor of the nasal cavity. A vertical incision is made, separating the nasal mucosa from the septum. The anterior septum is subluxed, the speculum is inserted, and the operating microscope or endoscope is brought into the field. The operation continues in a similar fashion to the endonasal approach just described.27

Neuronavigation

A TSA may be performed with frameless stereotactic neuronavigation to assist with large lesions that involve the carotid arteries or recurrent lesions where a prior operation has altered the normal anatomy.28,29 The operation is performed as just described; however, the surgeon is able to check his or her position at any point during the procedure to assess the proximity of surrounding structures or determine when he or she is approaching the limits of the tumor (Fig. 40.7).

Outcomes

Following operative decompression, vision generally improves and endocrine function recovers to a lesser extent, and surgical resection generally halts progressive loss of hormonal function. After TSA, visual field defects will improve in 70% to 89% of patients,30,31 will not change significantly in 7%, and will worsen in less than 4% of patients.32

Approximately 30% of patients with nonfunctioning adenomas have some degree of hypopituitarism prior to surgery.33 In one quarter of these patients, preoperative pituitary deficiencies will improve after surgery, although 10% of patients have some postoperative worsening of hormone function.8 Oral hormone replacement is generally sufficient for those patients whose pituitary deficiencies worsen or do not improve.

Complications from transsphenoidal surgery include intracranial hemorrhage, carotid artery injury, ischemic stroke, visual impairment, CSF leak, nasal septal perforation, and epistaxis. The risk of stroke or death is less than 1%, the risk of visual loss is less than 2%, and the risk of CSF rhinorrhea is less than 4%.34

Diabetes insipidus (DI) and the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH) are common but transient postoperative complications after transsphenoidal surgery. Nearly 18% of patients will develop DI, though this is often temporary.34 It is imperative to closely monitor fluid balance, serum sodium levels, and urine specific gravity. In a small number of patients, hyponatremia can occur a week or more after the surgery.

Following resection of a giant macroadenoma, when it is likely that some residual tumor may remain, a rare but potentially fatal complication is postoperative apoplexy. This complication must be closely monitored for. In one study of 134 surgically resected giant adenomas, four patients had fatal postoperative pituitary apoplexy.35

The mortality rate for patients undergoing transsphenoidal surgery is very low, approximately 0.5%. Among giant macroadenomas, the mortality rate is approximately 1%. After successful surgical resection, 10% to 20% of tumors are reported to recur within 6 years.30,31 At 10-year follow-up, more than 80% of patients who underwent transsphenoidal resection of a nonfunctioning pituitary adenoma are alive and disease free.8

Medical Therapy

Medical therapy is available for functioning tumors, but there are no available effective drug regimens for nonfunctioning pituitary adenomas. Multiple medical therapies have been tested. Dopamine agonists lead to a small reduction in tumor size in less than 10% of patients, and octreotide has improved visual deficits among some patients with macroadenomas.30,31 However, most patients with nonfunctioning pituitary tumors will gain no clinical or biochemical benefit from medical therapies.

Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy may be used in patients with recurrent or residual tumor, or in patients who cannot tolerate surgery. Radiotherapy controls tumor growth in 80% to 98% of nonfunctioning tumors.36

Conventional radiotherapy calls for fractionated doses of 1.6 to 2 Gy four or five times per week for 5 to 6 weeks, for a maximum dose of 45 to 50 Gy.9 Tumors respond slowly, with benefits delayed for a year or more.

Stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) uses only a single session to deliver focused radiation to the lesion with less radiation to surrounding structures. Several forms of SRS are available, including Gamma Knife surgery (GKS), linear accelerator (linac) radiation, and CyberKnife surgery. There is also fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy and proton beam therapy. SRS is generally able to use a higher radiation dose per fraction than is conventional radiation, and usually results in earlier endocrine control. It is not risk-free, however.

The major concern from SRS is radiation damage to the visual pathways, but this can be decreased by limiting the radiation dose to the optic chiasm to less than 10 Gy.37,38 Patients with adenomas closer than 2 to 5 mm to the optic chiasm or larger than 30 mm in diameter are generally not candidates for SRS, though they may undergo fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy or conventional radiation.39 The neuronal and vascular structures in the cavernous sinus are less radiosensitive, so an ablative dose may be administered to tumors with lateral invasion or impingement on the cranial nerves. This allows SRS to function as an adjuvant to surgical resection in patients with tumors that have invaded the cavernous sinus.

As with conventional radiotherapy, hormone deficiencies are the most common side effect with an incidence of 13% to 56%.40–43 The risks of radiation-induced second neoplasm and neuropsychiatric changes are lower with SRS than with conventional radiotherapy. Other side effects are rare. Long-term risk for radiation necrosis is approximately 0.2%. Optic neuropathy occurs in 1.7%, vascular changes in 6.3%, neuropsychological changes in 0.7%, and radiation-induced secondary malignancies in 0.8%.44 All forms of radiation therapy have delayed benefit, though SRS induces remission more rapidly than does fractionated radiotherapy.42,45

Follow-up

Routine postoperative evaluation with MRI and CT should be delayed for at least 4 to 6 weeks after surgery because of the difficulty analyzing the tumor region in the setting of recent surgical changes. Mass effect seen in the early postoperative period usually resolves and can be followed with serial MRI.46

Functioning Pituitary Adenomas

The majority of pituitary tumors are functioning adenomas. Of these, PRL-secreting tumors, or prolactinomas, account for 40% to 60%, while GH-secreting tumors make up 15% to 25%.47 Corticotropin-secreting adenomas represent about 5% of functioning adenomas, and gonadotropin- and thyrotropin-secreting tumors account for less than 1%. Neurohypophyseal tumors are very rare.

Prolactinoma

Prolactin Physiology

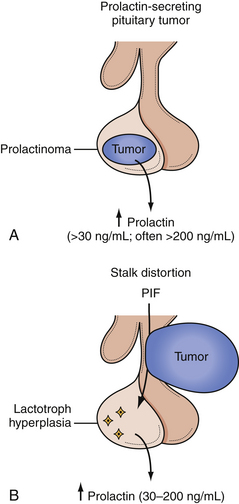

Lactotrophs secrete prolactin and are unique in that normal cells can proliferate during adulthood. PRL interacts with receptors in the gonads and acts on breast tissue to initiate and maintain lactation. Hypothalamic moderation of PRL secretion occurs by the release of dopamine into the portal circulation from nerve processes that originate in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus (Fig. 40.8). PRL release is increased by TRH, vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), GnRH, peptide histidine methionine, opiates, and estrogen. Pharmacological doses of TRH lead to a rapid release of PRL; however, the physiological role of TRH in PRL production is unclear.

During pregnancy, estrogen stimulates lactotroph hyperplasia and hyperprolactinemia but blocks the action of PRL on the breast, inhibiting lactation until after delivery. Within 4 to 6 months after delivery, basal PRL levels return to normal.

Incidence

Prolactinomas are second only to nonfunctioning adenomas in overall incidence, composing about 30% of all pituitary tumors and more than half of functional pituitary tumors. Hyperprolactinemia from a prolactin-secreting adenoma causes hypogonadism and galactorrhea.48–50 Women with hyperprolactinemia usually present with amenorrhea, galactorrhea, diminished libido, and infertility. Gonadal dysfunction and decreased estrogen secretion may lead to osteoporosis. In men, hyperprolactinemia manifests as diminished libido, impotence, gynecomastia, or infertility due to a decreased sperm count. Adolescents may present with delay of sexual development. In children and postmenopausal women, signs of hypogonadism may be absent.50

In autopsy studies, prolactinomas are found in equal numbers of men and women, but women are four times more likely to become symptomatic. Because they develop symptoms sooner, women more often present with smaller tumors, and men generally present with larger tumors and mass effect. Approximately 5% of women with primary amenorrhea and 52% with secondary amenorrhea not due to pregnancy have a prolactinoma, as do about 2% of men with impotence.51

Evaluation

Normal PRL levels are approximately 5 to 20 ng/mL in men and 5 to 25 ng/mL in nonpregnant women. Any sellar mass can compress the pituitary stalk and interrupt dopaminergic inhibition of PRL. This leads to a “stalk effect,” which results in mildly elevated PRL levels, generally 20 to 150 ng/mL, but should not be confused with a true prolactinoma. Serum PRL levels tend to correlate with the size of the prolactinoma, so that microadenomas generally lead to serum prolactin levels of 100 to 250 ng/mL, and macroadenomas may lead to a serum PRL well above 200 ng/mL. Invasive adenomas or giant adenomas may cause a serum PRL to be several thousand to 100,000 ng/mL.50,52,53 A PRL level more than 200 ng/mL is nearly pathognomonic for a prolactinoma. In patients with amenorrhea, however, pregnancy must also be excluded, as it is associated with PRL levels of 100 to 250 ng/mL by the third trimester. A PRL level of less than 2 ng/mL is generally associated with hypopituitarism, though this may be due to PRL-lowering medications.

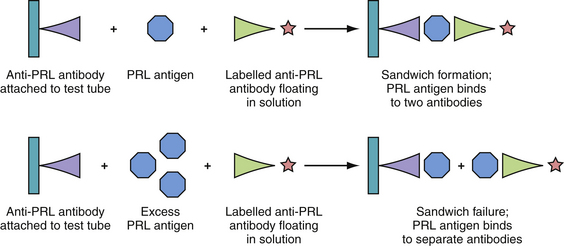

One must be suspicious of the “hook effect,” if prolactin values are very low in the presence of a suspected giant prolactinoma.54,55 If the serum PRL level is extremely high, the amount of prolactin-antigen may saturate the antibodies in the radioimmunoassay, failing to form the antigen plus two-antibody “sandwich” complexes required for accurate measurement, and thus leading to a falsely low value (Fig. 40.9). If a prolactinoma is suspected, the PRL level should be tested with serial dilutions to determine an accurate PRL value.52,56

Dopamine inhibits PRL secretion, so any drug that decreases dopamine levels will increase serum PRL. These drugs include many antidepressants, such as tricyclics, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, as well as methyldopa, reserpine, and verapamil.57 Other medications such as phenothiazines and metoclopramide block dopamine receptors, indirectly leading to increased PRL levels.57

Medical Treatment

Dopamine agonists are the treatment of choice for prolactinoma.58 These agents can normalize PRL levels within hours to days, shrink tumors, restore reproductive and sexual function, and allow patients to avoid the potential risks of surgery.

Current dopamine agonists, including bromocriptine, cabergoline, and pergolide, are synthetic derivatives of ergot alkaloids.59 Bromocriptine is begun orally once daily and increased over several weeks to multiple daily doses. It decreases tumor volume in approximately 85% of patients, and reduces PRL levels to normal in nearly 90%.50 Bromocriptine works very rapidly, often leading to a decrease in PRL within 1 to 2 hours. More than 10% of tumors are not sensitive to bromocriptine,60 and 5% to 10% of patients are intolerant of its gastrointestinal side effects, though intravaginal administration may lessen these symptoms.61

Cabergoline is more expensive than bromocriptine, but may be better tolerated, and is administered once or twice weekly.58 It normalizes PRL levels in up to 84% of patients.62 Studies of cabergoline in women of childbearing age are limited, but bromocriptine has been extensively studied and appears safe in pregnancy. Therefore, if pregnancy is desired, bromocriptine should be used,63 then discontinued during pregnancy unless symptomatic tumor enlargement occurs.

Medical treatment is generally continued chronically as cessation of either drug may result in recurrent hyperprolactinemia and tumor re-expansion.64 After initiation of medical therapy, MRI and visual examination should be repeated, and serum PRL levels should be monitored at least annually.65,66

One must be cautious with prolonged use of cabergoline and other ergot-derived dopamine agonists, as they may lead to an increased risk of pleural and pericardial fibrosing serositis and valvular heart disease when used in large doses, as they are in patients with Parkinson’s disease.67–69 Patients with prolactinoma receive significantly smaller doses of the drug than do patients receiving the drugs for parkinsonism, and it is unknown if the risk of symptomatic valvular heart disease exists at these low doses. Studies of echocardiograms in patients receiving cabergoline for hyperprolactinemia have reported conflicting results.70–74 There does not appear to be any statistical increase in incidence of clinically relevant or symptomatic cardiac regurgitation in patients treated with cabergoline. We recommend echocardiographic evaluation of patients who are receiving long-term, high-dose cabergoline.

Surgery

The effectiveness and safety of medical therapy have limited the need for surgery in most patients with prolactinoma. If a patient fails to respond to or is unable to tolerate the side effects of medical treatment, then surgery is recommended, as medication may be more effective after surgical debulking.75,76 Surgery is also suggested for patients who develop CSF leak while undergoing medical therapy or patients who have a dissociated response to drugs in which their prolactin level falls but the tumor does not shrink. TSA, as described previously, is the surgery of choice.34,77 An extended transsphenoidal approach may be needed if the tumor is beyond the sella, and craniotomy should be considered if there is significant extension.20,78

The higher the PRL level, the lower the chance of surgical cure. Patients with microprolactinomas and serum PRL level below 200 ng/mL have a greater than 90% chance of cure with TSA when performed by experienced pituitary surgeons at high-volume centers, and morbidity and mortality risks are less than 1%.34,75 However, patients with a preoperative PRL level above 200 ng/mL with large, invasive prolactinomas have a less than 41% surgical cure rate.76 In patients with giant or invasive prolactinomas, pretreatment with a dopamine agonist may improve the success of surgery; however, long-term pharmacotherapy can alter the tumor’s consistency and make surgery more challenging.79

Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy is an option for patients who have failed surgery or medical therapy.80,81 Though there is a risk of hypopituitarism or damage to the optic nerves, radiation therapy is generally considered safe and effective. Radiotherapy may be combined with medical or surgical management and may be delivered as conventional external beam radiotherapy or SRS.

Conventional radiotherapy regimens use approximately 4500 cGy in 25 to 30 fractions.82 Tumor growth is controlled in 83% to 100% of patients, and reduction in tumor mass is achieved in 36% to 45% of patients.83 SRS may provide more rapid endocrine control while permitting the delivery of radiation in a single session with less exposure to surrounding normal tissue.

Dopamine agonists may provide a radioprotective effect on tumors, and preferably should be discontinued during radiosurgery.80 In a study of 164 patients with prolactinoma who underwent primary treatment with Gamma Knife, tumor growth was controlled in all but two patients, and biochemical cure was attained in more than half.81

Growth Hormone–Secreting Adenomas

Growth Hormone Physiology

GH is required for normal human growth; it plays little role in the first year of life, but becomes very important during puberty. GH is required for normal linear growth and is secreted in pulses by the somatotroph cells. Its release is controlled by GHRH and somatostatin, which stimulate and inhibit release, respectively (Fig. 40.10). GH, in turn, stimulates the liver’s production of somatomedin-C, also known as insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1). IGF-1 inhibits GH secretion at the hypothalamus, where it stimulates somatostatin release, and at the pituitary, where it suppresses GHRH-induced GH secretion.

Sleep, stress, exercise, and hypoglycemia increase the release of GH, while obesity, hyperglycemia, and excess glucocorticoids decrease it. GH is anabolic and increases the uptake of amino acids into tissue; conversely, a rise in amino acids increases GH release in a healthy individual. GH and IGF-1 levels are highest in children and young adults, then decrease with age in normal subjects. In normal subjects, serum GH levels are very low or undetectable for most of the day. GH has a half-life of 20 to 30 minutes and is secreted in short pulses, with two to seven peaks per day, leading to significant fluctuations in levels during the day. Some of these bursts are associated with meals, while others occur during the early stages of sleep. The half-life of IGF-1, on the other hand, is 2 to 18 hours, and serum levels are relatively stable. IGF-1 measurements therefore provide a more reliable indication of the exposure of the body to GH than do GH measurements.

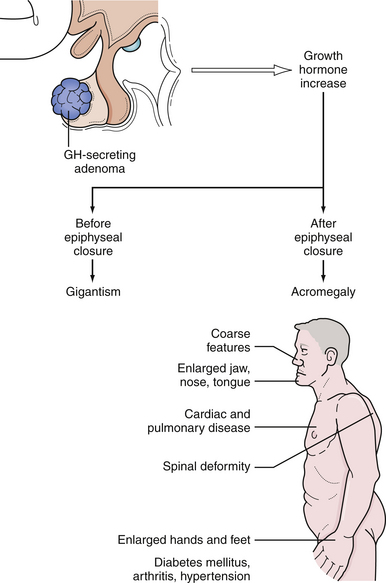

Growth Hormone Excess: Acromegaly

Excess GH secretion, which results in excess growth of the soft tissues, bony changes, and multiple biochemical changes, produces the syndromes of acromegaly in adults and gigantism in children who are affected before epiphyseal closure. Characteristics of acromegaly include coarse facial features with prognathism and malocclusion of the teeth, enlargement of the paranasal sinuses with frontal bossing, deepening of the voice, organomegaly, hyperhidrosis, acanthosis nigricans, enlargement of the hands and feet leading to an increase in ring, glove, and shoe size, and headache84–86 (Fig. 40.11). Insulin resistance can lead to diabetes mellitus. Tongue enlargement produces obstructive sleep apnea. Accumulation of excess soft tissue in the hands results in a wet, doughy handshake and in the feet it produces increased heel-pad thickness on radiographs. Patients with acromegaly also suffer from headache, proximal myopathy, osteoarthritis, carpal tunnel syndrome, cardiomegaly, and hypertension. Metabolic derangements lead to accelerated atherosclerosis and a shortened life expectancy as a result of cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and respiratory causes. There is also a higher risk of developing other neoplasms, especially colon cancer.1,87 With appropriate reduction of GH levels, however, mortality risk decreases and can normalize.88

The average annual incidence of acromegaly is approximately 3.3 per million.88 Ninety-eight percent of patients with acromegaly harbor a GH-secreting pituitary adenoma.89 From 20% to 50% of these tumors also secrete PRL or other pituitary hormones.90 Rarely, acromegaly is the result of ectopic GH-producing tumors such as bronchial carcinoid or pancreatic islet cell tumors, a hypothalamic GHRH-releasing tumor, exogenous administration of GH for antiaging treatments, or familial syndromes such as multiple endocrine neoplasia I, McCune-Albright syndrome, or Carney complex.89

The disease is generally insidious and presents in the third to fourth decade, and both sexes are equally affected.91 The average patient with acromegaly has had symptoms for 8 to 10 years before the diagnosis is made, so the majority of GH-secreting adenomas are large at the time of diagnosis.88 Many compress the optic system and produce loss of visual acuity or bitemporal hemianopia by the time the tumor is recognized.

Evaluation

When acromegaly or gigantism is suspected, endocrine evaluation should include measurement of basal GH and IGF-1 levels and testing to assess suppression of GH secretion by hyperglycemia (an oral glucose tolerance test, OGTT). Because exercise and stress stimulate GH secretion, serum GH levels are ideally obtained in the early morning before the patient arises from bed, or 2 hours after a meal when GH levels would normally be suppressed. In healthy subjects, basal GH levels are usually lower than 5 ng/mL, but more than 90% of acromegalic patients have levels higher than 10 ng/mL. Levels vary widely, however, so some acromegalic patients have normal GH levels. In patients with active acromegaly, the normal pulsatile GH secretory pattern is replaced by a consistent elevation of GH throughout the day. Owing to the short half-life and pulsatile pattern, random GH levels are of limited value and single determinations of GH correlate poorly with severity of disease. Serum GH levels may also be elevated in other conditions including uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, renal failure, malnutrition, and during physical or emotional stress.90 To confirm the diagnosis of acromegaly, an OGTT can be performed. In an acromegalic, GH will fail to suppress to less than 2 µg/L with glucose loading.

Because serum levels of IGF-1 are more stable than those of GH, measurement of IGF-1 can be used to provide a reliable indicator of the overall exposure of GH on the body. IGF-1 is increased in nearly all patients with acromegaly, even in those whose serum GH levels are within the range of normal. Normal levels of IGF-1 range from 0.45 to 2.2 U/mL in women and from 0.34 to 2.0 U/mL in men.90 Unlike GH, IGF-1 is not directly affected by stress or exercise, and it is bound to carrier proteins that regulate its function and stabilize its levels. IGF-1 is also a reliable parameter for posttreatment follow-up of acromegaly, because it reflects GH secretion over the prior 24 hours.85

TRH stimulation causes at least a 50% rise of GH in untreated acromegaly, whereas normal subjects generally have little change in serum GH in response to TRH injection. Though this finding also occurs in patients with liver disease, renal failure, or depression, it can be highly suggestive of acromegaly in the correct clinical setting. Acromegalic patients who have a positive response to TRH stimulation may respond to bromocriptine therapy. TRH stimulation may also be used to identify those patients who, despite a normal GH level after surgery, have residual GH-secreting tumor and are therefore at risk of tumor recurrence.92

Rarely, acromegaly is caused by a non-CNS GHRH-secreting tumor. Acromegalic patients who do not have a discrete pituitary tumor on MRI should be evaluated to find another site of a GHRH-secreting tumor. Measurement of plasma GHRH should be used. Ectopic acromegaly such as from a pancreatic islet cell tumor or bronchial carcinoid results in a measurable level of GHRH in the circulation, whereas GHRH is barely detectable when acromegaly is due to a pituitary lesion.93

Surgery

Surgical adenomectomy by an experienced neurosurgeon is the first-line treatment for acromegaly.18,19 A craniotomy may be necessary when there is a large tumor with extensive suprasellar or parasellar extension. Most GH-secreting tumors are sellar or suprasellar lesions that can be removed by the transsphenoidal route using a sublabial, transseptal, or direct endonasal approach with the endoscope or microscope, as described previously. Plasma GH levels may rapidly decrease within hours after surgery, and IGF-1 levels and clinical symptoms decrease over the next several weeks to months.18,94

Stringent criteria for a “cure” or remission require a random GH less than 2.5 µg/L, or GH nadir after an oral glucose tolerance test of less than 1 µg/L and a normal age and gender-normalized IGF-1, with no clinical symptoms.95 Using these strict criteria, a study of 59 patients followed for an average of 13.4 years after transsphenoidal surgery showed that 52% achieved long-term biochemical remission after surgery alone.96

About 20% to 25% of GH-secreting tumors are microadenomas, tumors less than 1 cm in diameter, while 75% to 80% are macroadenomas, more than 1 cm in diameter. In a study of 103 patients followed after TSA, remission was obtained postoperatively in 82% of patients with microadenomas, but in 60% of patients with macroadenomas, and only in 24% of patients with invasive macroadenomas.96 Several factors are predictive of surgical outcome, including tumor size, invasiveness, extrasellar growth, and secretory activity. Preoperative GH levels have an inverse relationship with the likelihood of biochemical remission following surgery.18,19,97,98

GH and IGF-1 levels should be followed 6 weeks postoperatively. If hormone levels are normal at that time, then the patient can be monitored with hormone assays annually, or more often if needed for concomitant conditions such as diabetes mellitus or hypopituitarism. If GH and IGF-1 levels have not normalized, and further treatment is needed, then medical therapy and radiotherapy are options. Reoperation for acromegaly has a lower success rate and higher complication rate than does initial surgery, and should be reserved for patients unresponsive to other forms of treatment or who have progressive visual impairment despite other treatments.99

Medical Therapy

Pharmacological options for acromegaly include somatostatin analogs, dopamine-receptor agonists, and GH-receptor (GHR) antagonists.100

Somatostatin acts as an endogenous inhibitor of GH secretion.101 Analogs are indicated for patients awaiting the effects of radiation and patients who are medically unstable for surgery or who have persistent disease after TSA.102 They can also be offered as primary therapy for patients who refuse surgery or those with severe medical conditions that preclude surgery or who are unlikely to be cured by an operation.102,103 Poor-risk patients may be reconsidered for surgery if their medical condition improves after several months on octreotide.104

Somatostatin analogs reduce GH and IGF-1 levels in 50% to 70% of acromegalic patients and normalize IGF-1 in 30% of patients who have failed pituitary surgery.105 Up to half of patients attain a decrease in the size of the pituitary tumor as well.102,104,106,107

First-generation somatostatin analogs, such as octreotide acetate, have a half-life that is 2 hours longer than that of the native hormone but still require subcutaneous administration multiple times daily.108,109 The maximum suppression of GH is reached within 2 hours and lasts about 6 hours. Relief of clinical symptoms is often immediate, even preceding the decrease in GH levels. Side effects associated with long-term use of octreotide are relatively minor and include pain at the injection site, abdominal cramps, mild steatorrhea, or impairment of glucose tolerance. Biliary sludge and cholesterol gallstones may occur after long-term treatment due to inhibition of gallbladder emptying.106,110 As with prolactinomas, discontinuation of medical therapy may result in rebound of pretreatment hormone levels and tumor size.

Newer somatostatin analogs have longer durations of action but similar efficacy and better compliance as compared to the older drugs.105 These long-acting somatostatin preparations are expensive and require a meticulous reconstitution technique before injection, necessitating long-term medical participation. Slow-release lanreotide (Somatulin SR) has a duration of action of 10 to 14 days, and requires injection two to three times per month, while slow-release depot octreotide (Sandostatin-LAR) requires an intramuscular injection only once every 28 days.105

Preoperative treatment with octreotide shrinks macroadenomas by about 40%.111 It is debatable, however, whether this affects surgical outcome. Two prospective, randomized studies demonstrated no benefit of preoperative octreotide on rate of hormone normalization postoperatively or on duration of hospital stay.112,113 A retrospective study of other acromegalic patients, on the other hand, found that IGF-1 levels normalized postoperatively in twice as many patients who had been treated with octreotide preoperatively as those who had not.104 Short-term preoperative octreotide administration decreases surgical risk in patients who have cardiac and metabolic complications of acromegaly.114 Octreotide should not be used in patients who are undergoing radiation therapy, as it may be radioprotective for some adenomas.80

If GH levels remain elevated despite maximized octreotide, then combined therapy with octreotide and dopamine-agonists is recommended.104 Although dopamine agonists increase GH release in normal subjects, they paradoxically suppress GH secretion in acromegalic patients. Dopamine agents appear to stimulate basal GH production in normal subjects by acting at the level of the hypothalamus, but they inhibit GH release from adenomas via direct action on dopamine receptors on the somatotroph cells.59

Bromocriptine is effective in lowering GH and IGF-1 levels in 20% of patients, with 10% achieving normalization.59,103,115 Bromocriptine should initially be given at a dose of 1.25 mg at bedtime and then increased slowly to a maximum of 20 mg per day in divided doses. Side effects such as nausea, nasal stuffiness, vertigo, and hypotension may result.

Cabergoline and quinagolide are among a newer generation of long-acting D2-receptor agonists that appear to be more effective and better tolerated than bromocriptine.40,104,116 Cabergoline’s serum half-life is 65 hours, requiring once or twice weekly administration. Quinagolide is given once daily. Long-term administration of cabergoline to 64 patients suppressed plasma IGF-1 levels to normal in 39% and achieved modest decreases in another 28%.40 Dopamine-agonists are most effective in mixed GH- and PRL-secreting tumors, which occur in 30% to 40% of acromegalic patients.115

GH receptor (GHR) dimerization is required for GH action. Pegvisomant is a mutated form of the GHR protein that acts as a GHR protein antagonist by binding to the GHR, blocking dimerization and thus inhibiting IGF-1 secretion.100,117,118 GHR antagonists do not act on the pituitary tumor directly, so a potential risk is an increase in GH secretion and tumor enlargement due to a loss of negative feedback from IGF-1. Studies suggest, however, that while there may be an increase in GH levels, it is not progressive and does not lead to a significant increase in tumor growth in patients followed for up to 2 years.100,117–120 One should therefore obtain regular MRI scans to monitor tumor size.

Pegvisomant is given as once daily subcutaneous injections and appears to be well tolerated. A randomized, double-blind multicenter trial of pegvisomant in 112 acromegalic patients demonstrated that when patients were treated with pegvisomant in 10-, 15-, and 20-mg doses, normalization of IGF-1 levels was achieved in 54%, 81%, and 89% of patients, respectively.100 Side effects appear to be minor. Some patients have been found to have asymptomatic hepatocellular injury after initiation of pegvisomant, but hepatic enzyme levels normalized after cessation of the drug.100,120

Pegvisomant should be considered in patients in whom surgery and medical therapy with somatostatin or dopamine agonists have proved ineffective or poorly tolerated.121

Estrogen receptor modulators are not a standard part of the acromegalic armamentarium, but research suggests that they may be of some benefit to selected patients. Estrogen can lower serum IGF-1 in patients with acromegaly and clinical symptoms of acromegaly often improve during pregnancy.122 Estrogen may suppress hepatic IGF-1 synthesis and alter GH signaling via its interaction with transcription pathways.122,123 A study using chronic tamoxifen, a partially competitive estrogen receptor antagonist, led to a transient increase in GH levels, but achieved a lasting decrease in IGF-1 with normalization of IGF-1 levels in 4 of 19 patients.124 A newer selective-estrogen modulator, raloxifene, was studied in 13 postmenopausal female patients, 9 of whom were resistant to somatostatin analog and dopamine agonist therapies. IGF-1 decreased by more than 30% in 10 patients, and normalized in 7.125 A study in male acromegalic patients demonstrated that raloxifene could successfully decrease IGF-1 levels; however, there was no change in clinical symptoms with raloxifene in male patients.126

Radiation Therapy

Radiotherapy should be considered for patients who are unsuitable for or have failed surgery and in whom medical therapy fails to achieve remission. Conventional radiotherapy is generally delivered in fractionated doses of 1.6 to 1.8 Gy four to five times weekly over 5 to 6 weeks, for a total dose of 45 to 59 Gy.127 There is a fall in GH levels in the first 2 years, followed by a slow continued decline thereafter.127–129 GH concentrations higher than 5 µg/L are achieved in 80% of patients within 10 to 15 years, though few patients are ever cured. A study followed acromegalic patients who received conventional external irradiation for an average of 12.8 years after radiotherapy; only one third of these patients achieved normal biochemical parameters.130

There are significant risks associated with radiotherapy. Hypopituitarism occurs in 30% to 70% of patients within 10 years after treatment.42 There are risks of visual changes from radiation effects on the optic nerve or chiasm and cognitive and neurological deficits from radiation necrosis in adjacent brain, and an increased risk for the development of secondary brain tumors such as gliomas.127,131 There are reports that conventional radiotherapy is associated with an increase in mortality rate from stroke among acromegalic patients.132

SRS has lower long-term risks of developing a second neoplasm or cognitive changes than does conventional radiation, and SRS induces remission more rapidly than does fractionated radiotherapy.42,45 In a report of Gamma Knife radiosurgery (GKS) for GH-secreting adenomas, GKS was used as the primary procedure in 68 of 79 patients. GH levels declined within 6 months in all cases, and GH levels normalized in 96% of the 45 patients who were followed for more than 2 years. Tumors shrank in 52% of patients after 12 months, 87% of patients after 24 months, and 92% of patients after 36 months or more.45 A small early series using CyberKnife radiosurgery demonstrated that 44% of patients achieved biochemical remission after an average 25 months of follow-up.43

Adrenocorticotropic Hormone–Secreting Adenomas

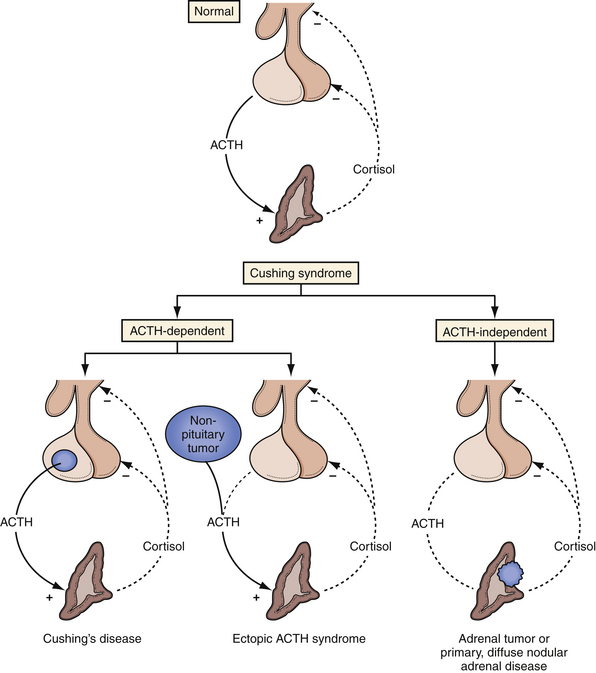

Cortisol Physiology: Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis

Cortisol is necessary for the maintenance of life and for the homeostatic biochemical and physiological responses to stress. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis regulates cortisol secretion (Fig. 40.12). Hypothalamic secretion of CRH occurs in response to signals from the brain to produce the circadian variation of plasma cortisol concentrations and in response to emotional, biochemical, and physical stressors. CRH then stimulates pituitary ACTH production and secretion in the corticotrophs. The adrenal glands secrete cortisol in response to ACTH.

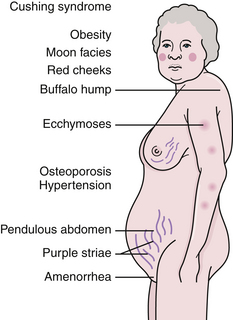

Cortisol Excess: Cushing’s Syndrome

Chronic exposure to excess cortisol produces Cushing’s syndrome. Generally, late evening plasma levels are elevated over the normal values of 5 to 25 ng/mL, and the usual diurnal variation is lost, leading to an elevated mean cortisol level. This chronic hypercortisolemia suppresses hypothalamic CRH and pituitary ACTH secretion, and the corticotroph cells atrophy.

Symptoms associated with Cushing’s syndrome include centripetal obesity, buffalo hump and supraclavicular fat pad, moon facies due to thickening of facial fat, facial telangiectasias, exophthalmos, hypertension, hyperglycemia or diabetes mellitus, hirsutism, acne, abdominal striae, amenorrhea or hypogonadism, muscle wasting and proximal myopathy, osteoporosis, hyperpigmentation, polyuria, and emotional disturbances including depression or psychosis (Fig. 40.13). Multiple organ systems are affected and, if untreated, the mortality rate is 50% within 5 years.133 Cardiovascular complications are a major cause of morbidity and death in untreated Cushing’s syndrome. Hypertension and congestive heart failure are common.

Cushing’s Disease

Cushing’s syndrome is a constellation of clinical signs and symptoms that accompany excess serum cortisol, and Cushing’s disease is the presence of pituitary corticotroph tumor and accounts for 70% to 80% of all cases of Cushing’s syndrome.133

Corticotroph cell adenomas fall into two categories: those that secrete ACTH and result in Cushing’s disease, and silent tumors, which contain ACTH but do not lead to clinical evidence of ACTH excess. Adenomas in Cushing’s disease are generally microadenomas. Macroadenomas are a rare cause of Cushing’s disease; they tend to be invasive and are quite difficult to treat. Cushing’s disease has a female predilection and usually occurs between the ages of 25 and 45 years. It is gradual in onset and runs a chronic course; most patients have symptoms for 3 to 6 years before diagnosis.133

In Cushing’s disease, the HPA axis maintains its homeostatic responses, but is altered to respond only to higher than normal glucocorticoid levels. Cushing’s syndrome from an ectopic ACTH-secreting tumor, on the other hand, will exhibit autonomous cortisol production and fail to react to any feedback inhibition (Fig. 40.14).

Cushing’s disease is unusual in children but does account for about one third of pediatric Cushing’s syndrome cases. When it does occur in children, it usually begins after puberty and affects the sexes equally. Cushing’s disease in children is manifested by impaired skeletal growth and obesity. Early treatment is imperative because resumption of normal growth can be achieved if patients are treated prior to epiphyseal fusion.134

Evaluation

The presence of normal sensitivity of the HPA axis to negative feedback by glucocorticoids should be assessed as well. This can be done with low-dose glucocorticoid tests including the overnight test or the low-dose portion of the 6-day dexamethasone suppression test. Cushing’s disease is diagnosed if a patient has (1) increased basal cortisol levels, (2) relative resistance to negative feedback from glucocorticoids, (3) ACTH response to decreased cortisol, (4) ACTH response to CRH or vasopressin, (5) cortisol response to exogenous ACTH, and (6) a pituitary source of the excess ACTH (Table 40.2).

TABLE 40.2 Clinical Approach to Patients Suspected of Having Cushing’s Syndrome

| Definitive Diagnosis of Cushing’s Syndrome |

| 1. Establish hypercortisolism:

or 2. Establish resistance to dexamethasone suppression: |

2. For diagnosis of ACTH-independent Cushing’s syndrome (adrenal disease):

3. For diagnosis of ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome:

High-dose dexamethasone suppression test

High-dose dexamethasone suppression test

Bilateral petrosal vein sampling for ACTH (with and without CRH)

Bilateral petrosal vein sampling for ACTH (with and without CRH)

4. Confirm diagnosis:

ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; CRH, corticotropin-releasing hormone; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Serum free cortisol filters into saliva and urine, so saliva and urine free cortisol levels are accurate indicators of increased cortisol secretion. Salivary cortisol is easy to use in an outpatient setting and allows for repeated sampling. An 11:00 PM salivary free cortisol greater than 3.6 nmol/L is highly suggestive of Cushing’s syndrome.

Patients with Cushing’s disease will generally suppress their levels to 50% of their baseline with the high-dose DST, but patients with ectopic ACTH tumors or adrenal tumors will not have any significant suppression. The Liddle test is a high-dose 6-day dexamethasone suppression test. A patient undergoes 2 days of baseline urinary 17-hydroxysteroid measurements, then is given 2 days of low-dose dexamethasone, 0.5 mg orally every 6 hours, and finally is given 2 days of high-dose dexamethasone, 2 mg orally every 6 hours. Liddle first observed in 1960 that most patients with a pituitary source of excess ACTH, Cushing’s disease, have a more than 50% decrease in 17-OHCS excretion on the second day of high-dose glucocorticoid administration, and that this response was not seen in patients with adrenal tumors.135

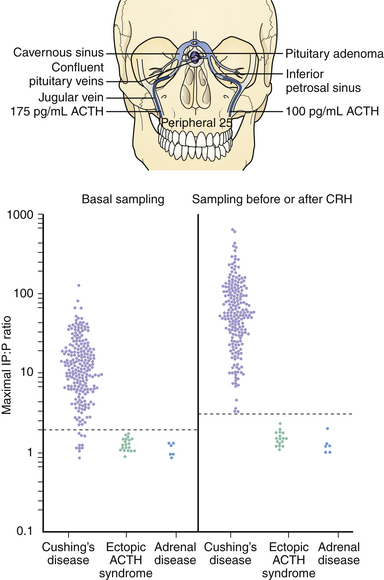

When Cushing’s disease is suspected, the location of the tumor must be established. If radiographic imaging does not demonstrate a lesion, inferior petrosal sinus sampling (IPSS) can be of assistance. Bilateral catheters are placed via the femoral veins and fed up the internal jugular veins to the inferior petrosal sinuses that drain the pituitary gland. ACTH levels are measured in the peripheral circulation and each sinus both before and after injection of CRH to stimulate ACTH secretion. Bilateral catheterization allows for simultaneous sampling of the right and left sinuses so that the ACTH concentrations can be compared. A gradient between the sinuses can lateralize the tumor within the pituitary. As spontaneous ACTH release is naturally episodic, CRH stimulation is given to ensure secretion at the time of sampling. An inferior petrosal sinus to peripheral blood (IPS:P) ratio greater than 2.0 in basal samples has up to 95% sensitivity and 100% specificity, while a peak IPS:P ratio greater than 3.0 after CRH administration has been reported to have 100% sensitivity and 100% specificity136–138 (Fig. 40.15). An intersinus gradient greater than 1.4 predicts the location of the lesion in up to 75% of patients. Cavernous sinus sampling is less commonly used, but can provide slightly more accurate localization.

Mild hyperprolactinemia is present in about one quarter of patients with Cushing’s disease, as some of these tumors contain PRL-secreting cells.139 PRL levels can also be measured as part of the IPSS to assist in localizing the tumor.

Surgery

Surgery is the first line of therapy for Cushing’s disease, achieving a high cure rate with low levels of morbidity and mortality.140 The majority of operations done for relief of Cushing’s disease are accomplished using a transsphenoidal approach. When a pituitary microadenoma is found intraoperatively and is successfully removed, up to 96% of patients will achieve remission.141,142 However, clinical recovery often takes 6 months or more. Long-term remission in patients with macroadenomas or tumors that invade parasellar structures is significantly lower, however, at 45% to 65%.141–143 Recurrence occurs in up to 25% of patients and increases progressively over time.144,145

Favorable prognostic features for surgery include definitive laboratory data, a visible tumor on preoperative MRI, and the discovery of an ACTH-staining tumor at surgery.146 Unfavorable prognostic factors include severe, rapidly progressive Cushing’s syndrome, an invasive tumor, and a macroadenoma.

Though the risks of TSA are relatively low, any surgery has associated complications. Some patients benefit from a short course of ketoconazole, a steroidogenesis inhibitor, to assist in stabilizing them prior to surgery. Cushingoid patients generally have multiple medical problems, including chronic hypercortisolemia and diabetes mellitus, which can make wound healing difficult. The risk of diabetes insipidus (DI) is almost 18% following surgery.34 Patients with Cushing’s disease are at increased risk for deep vein thrombosis, and hyponatremia and other electrolyte abnormalities can occur a few days after surgery, especially in patients who develop DI.

Radiation Therapy

Although conventional fractionated radiotherapy is effective in reducing the hypercortisolemia of Cushing’s disease, there is a significant delay before the full clinical and biochemical effect occurs. Remission occurs in 50% to 83% and can rise to 90% by 5 years after treatment.147,148 Though the latent period ranges from 4 to 60 months, remission usually starts after 9 months of treatment, and most patients are in remission within 2 years.147 A study followed long-term outcomes in 40 patients with Cushing’s disease who had failed surgery and were then treated with 45 to 50 Gy of conventional external beam radiotherapy in 25 to 28 fractions. Normalization of cortisol levels was achieved in 28% of patients 1 year after radiation, 73% of patients 3 years after treatment, 78% 5 years after treatment, and 84% 10 years after treatment.149 In the same study, pituitary hormone deficiencies developed in 62% of patients within 5 years after radiation, and 76% within 10 years.

SRS can be used as primary treatment for patients who are not good surgical candidates, and it can be a useful adjunct to surgery, medical therapy, or fractionated radiotherapy.150 The peripheral dose ranges from 25 to 40 Gy, and the dose to the optic nerves should not exceed 10 Gy.38,150,151 It is preferable to have a tumor less than 30 mm in diameter and a distance of at least 2 to 5 mm between the tumor and the optic chiasm.38,149

A marked decrease in the serum cortisol level is often obtained within 3 months after SRS; however, achievement of a biochemical cure may be delayed up to 3 years. The most common complication of SRS is hypopituitarism, which has been reported to occur in 16% to 55% of patients within 5 years following GKS.152 Optic neuropathy has been reported in less than 2% of cases and induction of a secondary neoplasm in less than 1% of cases. The risk of diabetes insipidus appears to be negligible with SRS.34

In a series of 90 patients who underwent Gamma Knife radiosurgery with a median marginal dose of 25 Gy, 49 achieved remission as defined by a normal 24-hour urine free cortisol level, with a 13-month mean time to remission.153 GKS can achieve remission in more than 60% of patients with Cushing’s disease who have failed surgery.154 Another report demonstrated that among 20 patients with Cushing’s disease who underwent GKS, there was complete resolution of the tumor on MRI in 30%, and levels of ACTH and cortisol normalized in 35%.151 Microadenomas appear to have a higher remission rate than do macroadenomas, and complications following SRS are less common in patients with microadenomas than in those with larger tumors.151,155

Repeat SRS after a patient has failed to go into remission may increase the risk that the patient will develop visual deficits or cranial nerve palsies, so repeat radiation is reserved only for those patients who are not candidates for surgery or pharmacotherapy.153

SRS with proton beam therapy has little damaging effect on tissues surrounding the tumor, can often be given in one session, and does not have the same radiation-induced side effects as does conventional radiotherapy.156 Proton beam therapy in patients with Cushing’s disease generally has a high efficacy, produces high remission rates, is relatively safe, and causes few cases of hypopituitarism. It can be used alone or in combination with unilateral adrenalectomy. In a study of 98 patients who received 80- to 90-Gy proton beam therapy, 90% had normalized hormone values and no clinical signs of disease in 6 to 36 months;156 94% of these patients remained in remission 3 to 5 years after radiation.

In fractionated stereotactic radiation therapy (fSRT), a dose of approximately 50 Gy in 1.8 to 2 Gy per fraction is delivered using multiple convergent beams. This process may reduce the risk of damage to the optic chiasm as compared to conventional radiotherapy.147 In a study of patients with Cushing’s disease who had previously failed surgery, complete remission occurred in 9 of 12 patients after a median of 29 months, with partial remission in the remaining patients.147 Another study compared 48 patients who received fSRT or linac-based SRS. Hormone levels normalized in 33% of the patients who received SRS and in 54% of the patients who received fSRT, after an average latency time of 8.5 months and 18 months, respectively.157

Interstitial irradiation, the transsphenoidal implantation of radioactive labeled yttrium-90 (90Y) or gold-198 (198Au) rods into the sella, is also a safe and effective treatment for Cushing’s disease. It does not have as long a latency period of external radiation and may induce remission faster than other nonsurgical options.158 In a study of 86 patients with Cushing’s disease who were treated with interstitial irradiation, the 1-year remission rate was 77%. There were no clinical or radiological relapses, though 37% of patients developed hypopituitarism.158

Medical Therapy

Steroidogenesis inhibitors, including ketoconazole, mitotane, and trilostane, decrease cortisol via direct enzymatic inhibition of steroidogenesis. Ketoconazole, a cytochrome P-450 enzyme inhibitor, is the best tolerated of these agents and effectively reduces plasma cortisol levels in about 70% of patients.159 In general, ACTH levels increase in patients with Cushing’s disease during chronic therapy with ketoconazole, suggesting that its major effect in these patients is on the adrenal cortex rather than the corticotrophs. A meta-analysis of 82 patients showed that treatment with ketoconazole alone reduced plasma cortisol levels in 70%. Patients with Cushing’s disease respond promptly with resolution of clinical and biochemical manifestations in 4 to 6 weeks; 600 to 800 mg per day total dosage is often required to normalize urinary free cortisol. Side effects include headache, sedation, nausea and vomiting, hepatotoxicity, gynecomastia, decreased libido, and impotence.

Mitotane achieves remission in up to 83% of patients, though only a third sustain remission after discontinuing treatment.160 Extensive metabolism of the drug is required, so a response may not occur for several months. Side effects include anorexia, diarrhea, ataxia, gynecomastia, hypercholesterolemia, hypouricemia, leukopenia, and arthralgias. Mitotane is relatively contraindicated in women desiring fertility as it may act as a teratogen even years after discontinuation due to gradual release from adipose tissue. Metyrapone is an 11β-hydroxylase inhibitor that may also inhibit ACTH secretion directly at high doses. It can be useful as monotherapy or in combination with radiation. Nausea, dizziness, and rash may limit its use, and it can lead to an increase in androgens and hypertension.

Neuromodulatory compounds, such as bromocriptine and valproic acid, reduce ACTH release from the tumor. Response rates are poor, but no large-scale placebo-controlled trials have been reported. Approximately 40% of patients in case reports and small series normalized urine or plasma glucocorticoids with chronic bromocriptine therapy.161 Valproic acid decreased ACTH concentrations in patients receiving the drug to inhibit seizures. However, despite case reports suggesting efficacy, placebo-controlled studies do not support its use as monotherapy.161

Mifepristone (RU486) competitively antagonizes glucocorticoid, androgen, and progestin receptors to inhibit the action of endogenous ligands. Its use in Cushing’s syndrome has been limited to a few investigations of patients with ectopic ACTH secretion and one patient with Cushing’s disease.162 Rosiglitazone, a thiazolidinedione compound with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor g (PPARg)–binding affinity, suppresses ACTH secretion in tumors and inhibits tumor cell growth. In patients with Cushing’s disease, rosiglitazone reduced cortisol secretion and lowered plasma ACTH; urinary free cortisol levels normalized 30 to 60 days after administration.163

Adrenalectomy and Nelson Syndrome

Following bilateral adrenalectomy, the loss of the inhibitory effects of the excess cortisol on a pituitary tumor’s ACTH secretion and growth leads to very high levels of plasma ACTH. These levels may suffice to increase skin pigmentation and cause progression of the ACTH-secreting pituitary tumor, which occasionally becomes invasive or even metastatic. This is known as Nelson syndrome and the prevalence after adrenalectomy ranges from 8% to 42%.164–166 These invasive tumors are unlikely to be cured with TSA; in one study, only 5 of 11 patients with Nelson syndrome achieved remission after surgery.167 Prior to adrenalectomy, pituitary radiation is often recommended to decrease the risk of developing Nelson syndrome.

Gonadotropin-Secreting Adenomas

Gonadotropin Physiology

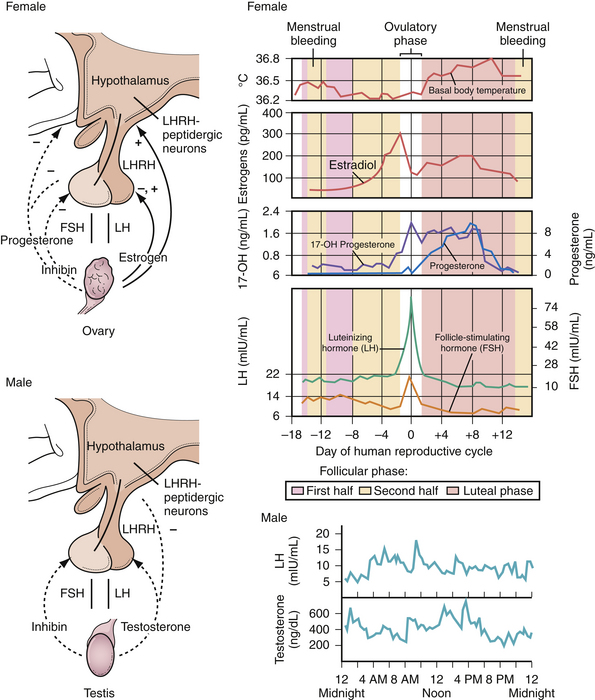

FSH and LH are produced and released by the gonadotrophs of the adenohypophysis to regulate ovarian and testicular function (Fig. 40.16). In women, FSH stimulates growth of the granulosa cells of the ovarian follicle and controls their estrogen secretion. At the midpoint of the menstrual cycle, the increasing level of estradiol stimulates a surge of LH secretion, which then triggers ovulation. After ovulation, LH supports the formation of the corpus luteum. Exposure of the ovary to FSH is required for expression of the LH receptors. In men, LH is responsible for the production of testosterone by Leydig cells in the testes. The combined effects of FSH and testosterone on the seminiferous tubule stimulate sperm production.

Thyroid Stimulating Hormone–Secreting Adenomas

Pituitary-Thyroid Axis

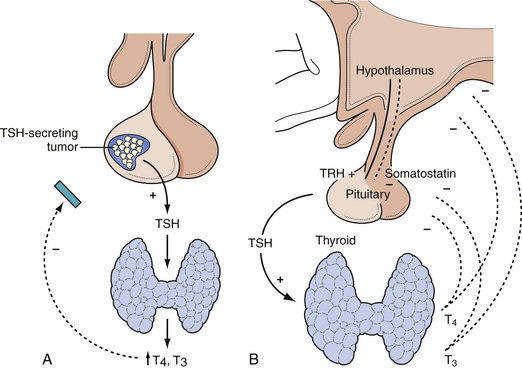

Production and secretion of the thyroid hormones thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3) are regulated via hypothalamic secretion of TRH into the portal venous system. In response to TRH the thyrotropes release TSH, which acts on the thyroid gland to release T4 and T3. Both T3 and T4 inhibit TRH secretion by the hypothalamus and TSH release by the pituitary (Fig. 40.17). Somatostatin, glucocorticoids, and dopamine also suppress both TRH release and the pituitary response to TRH.

Hyperthyroidism or Hypothyroidism

The production of α- and β-subunits is imbalanced such that excess α-subunit is secreted, which produces a ratio of plasma α-subunit to plasma TSH of more than 1.0. In a patient with hyperthyroidism, an elevated TSH level combined with an elevated ratio of the molar concentration of α-subunit to TSH indicates the presence of a TSH-secreting pituitary adenoma and calls for further evaluation of the pituitary. Many TSH-secreting pituitary tumors also secrete GH or PRL. These adenomas are chromophobic and stain positively for the α-subunit as well as the β-subunit of TSH.

Pituitary Apoplexy

Pituitary apoplexy is a life-threatening condition in which a tumor undergoes sudden hemorrhage or infarction. The lesion rapidly expands, resulting in acute compression of the pituitary gland, optic nerves, and cavernous sinus. Presenting symptoms include sudden headache, emesis, visual loss, ophthalmoplegia, impaired consciousness, and acute hormonal insufficiency.35,171

Visual field deficits and hormonal abnormalities may be permanent after apoplexy. However, patients who undergo surgery within a few days of the apoplectic event have a significantly higher chance of recovering visual loss than do those in whom surgery is delayed by a week or more.171,172

Fortunately this condition is quite rare. Although clinically asymptomatic infarct or hemorrhage has been documented in up to 25% of pituitary adenomas,173 clinically significant apoplexy is much less common. About 50% of patients with apoplexy have nonfunctioning adenomas.172 Radiation treatment, endocrine changes, anticoagulation, and severe systemic illness increase the risk of an apoplectic event; however, most cases appear to have no identifiable precipitating cause.171

Pediatric Adenomas

Pituitary adenomas are rare in the pediatric population, accounting for less than 3% of supratentorial pediatric tumors, and occurring at an incidence of 0.1 per 1 million children.174 Owing to the location of the gland and the importance of anterior pituitary hormones on puberty, pituitary adenomas can cause significant morbidity including delay in puberty and oligomenorrhea. The majority of pituitary lesions found in pediatric patients are macroadenomas,175 and tumor size is often proportional to endocrine and neurological dysfunction. Thus, earlier diagnosis may lead to better outcome. Adolescent patients with growth or pubertal abnormalities therefore should undergo evaluation for a possible pituitary lesion.176

Chandler W.F., Barkan A.L. Treatment of pituitary tumors: a surgical perspective. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2008;37:51-66.

Ciric I., Ragin A., Baumgartner C., et al. Complications of transsphenoidal surgery: results of a national survey, review of the literature, and personal experience. Neurosurgery. 1997;40:225-237.

Jagannathan J., Yen C.-P., Pouratian N., et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery for pituitary adenomas: a comprehensive review of indications, techniques and long-term results using the Gamma Knife. J Neurooncol. 2009;92:345-356.

Liu J.K., Weiss M.H., Couldwell W.T. Surgical approaches to pituitary tumors. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 2003;14:93-107.

Oyesiku N. Multimodality treatment of pituitary adenomas. Clin Neurosurg. 2005;52:234-242.

Please go to expertconsult.com to view the complete list of references.

1. Clayton R.N. Sporadic pituitary tumours: from epidemiology to use of databases. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;13:451-460.

2. Buurman H., Saeger W. Subclinical adenomas in postmortem pituitaries: classification and correlations to clinical data. Euro J Endocrinol. 2006;154:753-758.

3. Monson J.P. The epidemiology of endocrine tumours. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2000;7(1):29-36.

4. Clayton R.N., Stewart P.M., Shalet S.M., Wass J.A. Pituitary surgery for acromegaly should be done by specialists. BMJ. 1999;319(7210):588-589.

5. Burrow G.N., Wortzman G., Rewcastle M.B., et al. Microadenomas of the pituitary and abnormal sellar tomograms in an unselected autopsy series. N Engl J Med. 1981;304:156-158.

6. Arita K., Tominaga A., Sugiyama K., et al. Natural course of incidentally found nonfunctioning pituitary adenoma, with special reference to pituitary apoplexy during follow-up examination. J Neurosurg. 2006;104:884-891.

7. Jane J.A.Jr., Laws E.R.Jr. The management of non-functioning pituitary adenomas. Neurol India. 2003;51(4):461-465.

8. Jane J.A.Jr., Laws E.R.Jr. Chapter 13: Surgical management of pituitary adenomas. http://www.endotext.org/neuroendo/neuroendo13/neuroendoframe13.htm. 2004.

9. Colin P., Jovenin N., Delemer B., et al. Treatment of pituitary adenomas by fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy: a prospective study of 110 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;62(2):333-341.

10. Al-Shraim M., Asa S.L. The 2004 World Health Organization classification of pituitary tumors: what is new? Acta Neuropathol. 2006;111:1-7.

11. Ragel B.T., Couldwell W.T. Pituitary carcinoma: a review of the literature. Neurosurg Focus. 2004;16(4):1-9.

12. Asa S.L., Kovacs K. Clinically non-functioning human pituitary adenomas. Can J Neuro Sci. 1992;19(2):228-235.

13. Katznelson L., Alexander J.M., Klibanski A. Clinically nonfunctioning pituitary adenomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;76(5):1089-1094.

14. Greenman Y., Melmed S. Diagnosis and management of nonfunctioning pituitary tumors. Annu Rev Med. 1996;47:95-106.

15. Flickinger J.C., Nelson P.B., Martinez A.J., et al. Radiotherapy of nonfunctional adenomas of the pituitary gland. Results with long-term follow-up. Cancer. 1989;63:2409-2414.

16. Greenman Y., Melmed S. Diagnosis and management of nonfunctioning pituitary tumors. Annu Rev Med. 1996;47:95-106.

17. Mortini P., Losa M., Barzaghi R., et al. Results of transsphenoidal surgery in a large series of patients with pituitary adenoma. Neurosurgery. 2005;56(6):1222-1233.

18. Abosch A., Tyrrell J.B., Lamborn K.R., et al. Transsphenoidal microsurgery for growth hormone-secreting pituitary adenomas: initial outcome and long-term results. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83(10):3411-3418.

19. Tindall G.T., Oyesiku N.M., Watts N.B., et al. Transsphenoidal adenomectomy for growth hormone-secreting pituitary adenomas in acromegaly: outcome analysis and determinants of failure. J Neurosurg. 1993;78(2):205-215.

20. Kaptain G.J., Vincent D.A., Sheehan J.P., Laws E.R.Jr. Transsphenoidal approaches for the extracapsular resection of midline suprasellar and anterior cranial base lesions. Neurosurgery. 2001(49):94-100.

21. Alleyne C.H.J., Barrow D.L., Oyesiku N.M. Combined transsphenoidal and pterional craniotomy approach to giant pituitary tumors. Surg Neurol. 2002;57:380-390.

22. Colao A., Ferone D., Cappabianca P., et al. Effect of octreotide pretreatment on surgical outcome in acromegaly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82(10):3308-3314.

23. Cohen-Gadol A.A., Liu J.K., Laws E.R.Jr. Cushing’s first case of transsphenoidal surgery: the launch of the pituitary surgery era. J Neurosurg. 2005;103:570-574.

24. Kante A.S., Dumont A.S., Asthagiri A.R., et al. The transsphenoidal approach: a historical perspective. Neurosurg Focus. 2005;18(4):e6.

25. Jho H.D., Alfieri A. Endoscopic endonasal pituitary surgery: evolution of surgical technique and equipment in 150 operations. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2001;44:1-12.

26. Jho H.D. Endoscopic transsphenoidal surgery. J Neurooncol. 2001;54:187-195.

27. Zada G., Kelly D.F., Cohan P., et al. Endonasal transsphenoidal approach for pituitary adenomas and other sellar lesions: an assessment of efficacy, safety, and patient impressions. J Neurosurg. 2003;98:350-358.

28. Jane J.A.Jr., Thapar K., Alden T.D., Laws E.R.Jr. Fluoroscopic frameless stereotaxy for transsphenoidal surgery. Neurosurgery. 2001;48:1302-1308.

29. Yano S., Kawano T., Kudo M., et al. Endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal approach through the bilateral nostrils for pituitary adenomas. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2009;49(1):1-7.

30. Shimon I., Melmed S. Management of pituitary tumors. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:472-483.

31. Orrego J.J., Barkan A.L. Pituitary disorders. Drug treatment options. Drugs. 2000;59:93-106.

32. Powell M. Recovery of vision following transsphenoidal surgery for pituitary adenomas. Br J Neurosurg. 1995;9(3):367-373.

33. Flickinger J.C., Nelson P.B., Martinez A.J., et al. Radiotherapy of nonfunctional adenomas of the pituitary gland. Results with long-term follow-up. Cancer. 1989;63:2409-2414.

34. Ciric I., Ragin A., Baumgartner C., et al. Complications of transsphenoidal surgery: results of a national survey, review of the literature, and personal experience. Neurosurgery. 1997;40:225-237.

35. Ahmad F.U., Pandey P., Mahapatra A.K. Postoperative “pituitary apoplexy” in giant pituitary adenomas: a series of cases. Neurol India. 53(3), 2005. 326–328

36. Milker-Zabel S., Debus J., Thilmann C., et al. Fractionated stereotactically guided radiotherapy and radiosurgery in the treatment of functional and nonfunctional adenomas of the pituitary gland. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;50:1279-1286.

37. Jackson I.M., Noren G. Gamma knife radiosurgery for pituitary tumours. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;13:461-469.

38. Jagannathan J., Yen C.-P., Pouratian N., et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery for pituitary adenomas: a comprehensive review of indications, techniques and long-term results using the Gamma Knife. J Neurooncol. 2009;92:345-356.

39. Petrovich Z., Jozsef G., Yu C., Apuzzo M. Radiotherapy and stereotactic radiosurgery for pituitary tumors. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 2003;14(1):147-166.

40. Abs R., Verhelst J., Maiter D., et al. Cabergoline in the treatment of acromegaly: a study in 64 patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83(2):374-378.

41. Benveniste R.J., King W.A., Walsh J., et al. Repeated transsphenoidal surgery to treat recurrent or residual pituitary adenoma. J Neurosurg. 2005;102:1004-1012.

42. Powell J.S., Wardlaw S.L., Post K.D., Freda P.U. Outcome of radiotherapy for acromegaly using normalization of insulin-like growth factor I to define cure. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(5):2068-2071.

43. Roberts BK, Ouyang DL, Lad SP, et al. Efficacy and safety of CyberKnife radiosurgery for acromegaly. Pituitary. 207;10(1):19–25.

44. Becker G., Kocher M., Kortmann R.D., et al. Radiation therapy in the multimodal treatment approach of pituitary adenoma. Strahlenther Onkol. 2002;178(4):173-186.

45. Zhang N., Pan L., Wang E.M., et al. Radiosurgery for growth hormone-producing pituitary adenomas. J Neurosurg. 2000;93(Suppl 3):6-9.

46. Rajaraman V., Schulder M. Postoperative MRI appearance after transsphenoidal pituitary tumor resection. Surg Neurol. 1999;52:592-598.

47. Vance M.L., Thorner M.O. Prolactinomas. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1987;16:731-753.

48. Molitch M.E. Diagnosis and treatment of prolactinomas. Adv Intern Med. 1999;44:117-153.

49. Molitch M.E. Medical treatment of prolactinomas. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1999;28:143-169.

50. Liu J., Couldwell W. Contemporary management of prolactinomas. Neurosurg Focus. 2004;16(4):E2.

51. Weiss M. Pituitary tumors: an endocrinological and neurosurgical challenge. Clin Neurosurg. 1992;39:114-122.

52. Fleseriu M., Lee M., Pineyro M.M., et al. Giant invasive pituitary prolactinoma with falsely low serum prolactin: the significance of “hook effect.”. J Neurooncol. 2006;79:41-43.

53. Oyesiku N. Multimodality treatment of pituitary adenomas. Clin Neurosurg. 2005;52:234-242.

54. Frieze T.W., Mong D.P., Koops M.K. “Hook effect” in prolactinomas: case report and review of literature. Endocr Pract. 2002;8:296-303.

55. St-Jean E., Blain F., Comtois R. High prolactin levels may be missed by immunoradiometric assay in patients with macroprolactinomas. Clin Endocrinol. 1996;44:305-309.

56. Unnikrishnan A.G., Rajaratnam S., Seshadri M.S., et al. The “hook effect” on serum prolactin estimation in a patent with macroprolactinoma. Neurol India. 2001;49:78-80.

57. David S., Taylor C., Kinon B., et al. The effects of olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol on plasma prolactin levels in patients with schizophrenia. Clin Ther. 2000;22:1085-1096.

58. Molitch M.E. Medical management of prolactin-secreting pituitary adenomas. Pituitary. 2002;5:55-65.

59. Jaffe C.A., Barkan A.L. Treatment of acromegaly with dopamine agonists. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1992;21(3):713-735.

60. Caccavelli L., Feron F., Morange I., et al. Decreased expression of the two D2 dopamine receptor isoforms in bromocriptine-resistant prolactinomas. Neuroendocrinology. 1994;60:314-322.

61. Katz E., Schran H.F., Adashi E.Y. Successful treatment of a prolactin-producing pituitary macroadenoma with intravaginal bromocriptine mesylate: a novel approach to intolerance of oral therapy. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;73:517-520.

62. Verhelst J., Abs R., Maiter D., et al. Cabergoline in the treatment of hyperprolactinemia: a study in 455 patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:2518-2522.

63. Ricci E., Parazzini F., Motta T., et al. Pregnancy outcome after cabergoline treatment in early weeks of gestation. Reprod Toxicol. 2002;16:791-793.

64. Orrego J.J., Chandler W.F., Barkan A.L. Rapid re-expansion of a macroprolactinoma after early discontinuation of bromocriptine. Pituitary. 2000;3:189-192.

65. Bevan J.S., Webster J., Burke C.W., et al. Dopamine agonists and pituitary tumor shrinkage. Endocr Rev. 1992;13:220-240.

66. Ciccarelli E., Camanni F. Diagnosis and drug therapy of prolactinoma. Drugs. 1996;51:954-965.

67. Zanettini R., Antonini A., Gatto G., et al. Valvular heart disease and the use of dopamine agonists for Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:39-46.

68. Schade R., Andersohn F., Suissa S., et al. Dopamine agonists and the risk of cardiac-valve regurgitation. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:29-38.