170 Pituitary Apoplexy

• Pituitary apoplexy is a rare but serious condition caused by hemorrhage or infarction of the pituitary gland.

• Patients are seen acutely with severe headache, meningismus, visual field deficits, cranial nerve palsies, loss of visual acuity, and altered mental status.

• Acute hypopituitarism may develop following pituitary apoplexy. Treatment of impending adrenal crisis is mandatory.

• Emergency consultation with a neurosurgeon who has expertise in pituitary surgery and management is required.

Epidemiology

Pituitary adenomas are common, with a prevalence of 3% to 27% in various autopsy series. They are rarely diagnosed in life, with a reported incidence of 4 per 100,000 in a Finnish population and a prevalence of 77 per 100,000 in a British one.1,2 Apoplexy occurs in a minority of such lesions and can occasionally be seen with normal glands. Because of the relative rarity of this condition, pituitary apoplexy may be confused with more common entities such as subarachnoid hemorrhage. Delay in diagnosis and treatment may lead to blindness, permanent cranial nerve palsies, or death.3,4

Pathophysiology

Tumors involved in apoplexy are typically nonfunctional and unsuspected macroadenomas. In patients undergoing an endocrine stimulation test for hypogonadism, hypothyroidism, or adrenal insufficiency, apoplexy may occasionally develop secondary to stimulation of a macroadenoma. Treatment of a pituitary tumor can also precipitate apoplexy, particularly in cases of surgery, irradiation, or bromocriptine administration. Other reported risk factors include pregnancy (Sheehan syndrome), head trauma, recent cardiac surgery, anticoagulation, hypertension, diabetic ketoacidosis, and ovarian stimulation medications.5

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Classic

The findings in patients with pituitary apoplexy vary from mild headache to sudden collapse and coma. Most patients exhibit severe frontal or retroorbital headache, vomiting, impaired visual acuity, visual field defects, hypopituitarism, and subsequent adrenal crisis. A minority have ocular palsies, obtundation, meningismus, blindness, or long-tract signs. The visual field deficit is classically bitemporal upper quadrantopia or hemianopia. Associated cerebral infarction occasionally occurs secondary to vasospasm from subarachnoid hemorrhage or direct compression of the internal carotid artery by tumor. Table 170.1 lists the frequency of signs and symptoms reported in four case series.3,5–7

| SIGN OR SYMPTOM | FREQUENCY (% INCIDENCE) |

|---|---|

| Headache | 63-97 |

| Visual field deficit | 43-82 |

| Hypopituitarism | 81 |

| Adrenal crisis | 65 |

| Vomiting | 50 |

| Visual impairment | 60 |

| Complete blindness | 10 |

| Ocular palsies | 40-46 |

| Meningismus | 25 |

| Altered mental status | 13 |

| Hyponatremia | 12 |

| Long-tract signs | 5 |

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

Common neurologic emergencies can be confused with pituitary apoplexy (Box 170.1). The sudden onset of severe headache suggests subarachnoid hemorrhage. Obtundation and meningeal signs suggest meningitis, cerebral hemorrhage, or cerebral venous thrombosis. Cranial nerve findings in the setting of altered mental status may indicate cavernous sinus thrombosis or midbrain infarction. Rare hypothalamic and pituitary compressive or destructive processes may closely mimic apoplexy because of accompanying headaches and visual field deficits. Two such mimics are lymphocytic hypophysitis and Rathke cleft cysts. Pediatric craniopharyngiomas and several primary and metastatic lesions in adults may also compress the pituitary gland and mimic apoplexy. Generally, deficits in visual acuity and visual fields raise suspicion for apoplexy in the appropriate clinical setting.

Box 170.1 Differential Diagnosis

Sudden severe headache with or without changes in mental status or long-tract signs

• Subarachnoid hemorrhage, meningitis, cerebral hemorrhage, mass, infarction, intracranial venous thrombosis

Severe headache with decreased visual acuity, ocular palsies, or visual field changes

• Complicated migraine, cavernous sinus thrombosis, cerebellar hemorrhage, midbrain infarction

Signs of hypogonadism, hypoadrenalism, or hypothyroidism

• Causes of hypopituitarism, including remote head injury, lymphocytic hypophysitis, iatrogenic surgical or radiation injury, and infections (particularly tuberculosis and mycotic infections); consider primary hypoadrenalism and hypothyroidism

Diagnostic Testing

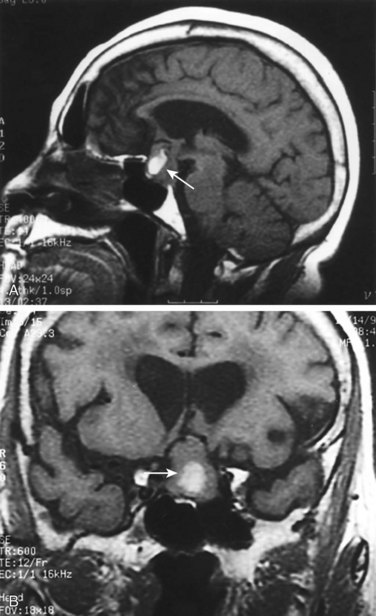

Visual acuity and confrontational visual field testing should be performed when the diagnosis of pituitary apoplexy is considered. Samples should be obtained for electrolytes, renal function, liver function, clotting screen, blood counts, random cortisol, thyroxine, TSH, PRL, insulin-like growth factor, GH, LH, FSH, and testosterone in men and estradiol in women.8 A non–contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan of the head will exclude the diagnosis of acute subarachnoid hemorrhage. Endocrine simulation testing could worsen the condition and should be deferred. Computed tomography is not sufficiently sensitive to exclude a pituitary process. Contrast-enhanced, diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging allows the best visualization of pituitary tumors and details of the hemorrhage and infarction within them (Fig. 170.1, A and B).9

Management

There is controversy regarding conservative treatment with steroids versus surgical intervention.8,10,11 Patients with minimal or improving visual symptoms are sometimes managed medically. Definitive treatment is pituitary decompression, most often through a transsphenoidal approach. The outcome depends on the severity of symptoms at initial evaluation and prompt decompression of the sella turcica. Early diagnosis and treatment improve outcome and visual acuity; any residual hypopituitarism generally persists.6,7

![]() Priority Actions

Priority Actions

Do

Fingerstick glucose test; treat if hypoglycemic.

Draw blood for serum cortisol, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and free T4 (thyroxine).

Administer parenteral hydrocortisone, 100 mg four times daily, or dexamethasone, 4 mg twice daily.

Provide fluid and electrolyte support.

Perform computed tomography to exclude subarachnoid hemorrhage, followed by magnetic resonance imaging.

Initiate early consultation with an endocrinologist and neurosurgeon with pituitary expertise.

Biousse V, Newman NJ, Oyesiku NM, et al. Precipitating factors in pituitary apoplexy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71:542–545.

Maccagnan P, Macedo CL, Kayath MJ, et al. Conservative management of pituitary apoplexy: a prospective study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80:2190–2197.

Rajasekarn S, Vanderpump M, Baldeweg S, et al. UK guidelines for the management of pituitary apoplexy. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2011;74:9–20.

Semple PL, Webb MK, de Villiers JC, et al. Pituitary apoplexy. Neurosurgery. 2005;56:65–72.

1 Raappana A, Koivukangas J, Ebeling T, Pirilä T. Incidence of pituitary adenomas in Northern Finland in 1992-2007. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:4268–4275.

2 Fernandez A, Karavitaki N, Wass JA. Prevalence of pituitary adenomas: a community-based, cross-sectional study in Banbury (Oxfordshire, UK). Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2010;72:377–382.

3 Semple PL, Webb MK, de Villiers JC, et al. Pituitary apoplexy. Neurosurgery. 2005;56:65–72.

4 Agrawal D, Mahapatra AK. Visual outcome of blind eyes in pituitary apoplexy after transsphenoidal surgery: a series of 14 eyes. Surg Neurol. 2005;63:42–46.

5 Biousse V, Newman NJ, Oyesiku NM, et al. Precipitating factors in pituitary apoplexy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71:542–545.

6 Ayuk J, McGregor EJ, Mitchell RD, et al. Acute management of pituitary apoplexy—surgery or conservative management? Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2004;61:747–752.

7 Lubina A, Olchovsky D, Berezin M, et al. Management of pituitary apoplexy: clinical experience with 40 patients. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2005;147:151–157.

8 Rajasekarn S, Vanderpump M, Baldeweg S, et al. UK guidelines for the management of pituitary apoplexy. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2011;74:9–20.

9 Pisaneschi M, Kapoor G. Imaging the sella and parasellar region. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2005;15:203–219.

10 Maccagnan P, Macedo CL, Kayath MJ, et al. Conservative management of pituitary apoplexy: a prospective study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80:2190–2197.

11 Woo HJ, Hwang JH, Hwang SK, et al. Clinical outcome of cranial neuropathy in patients with pituitary apoplexy. J Korean Neursurg Soc. 2010;48:213–218.