Chapter 12 Physical and Neurologic Examination

History Taking

Careful review of the patient’s past medical history is important to uncover conditions with symptoms commonly seen in patients with spinal pathology. Diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, inflammatory arthropathies, and neoplastic disorders are common examples. Any history of trauma involving the spine and related surgical procedures should be noted, in addition to injuries involving the shoulder, hip, and long bones. Unrecognized compression neuropathies secondary to casting, for example, can subsequently be confused with radiculopathy. Retroperitoneal hematoma may present as a femoral or an upper lumbar radiculopathy.1 It is also important to inquire about a history of any psychiatric disorders and pain syndromes associated with joints, muscles, or connective tissues. Fibromyalgia and reflex sympathetic dystrophy can alter perioperative pain management and may require additional attention. Inquiry about smoking history is also important because smoking has been demonstrated to increase the incidence of pseudarthrosis compared with nonsmoking.2

General Physical Examination

Although a comprehensive general physical examination may not be feasible in every patient, details gathered from the patient’s medical history serve as a guide to performing an examination of other organ systems. Basic vital signs should be recorded in most patients. Hypertension and atrial fibrillation are two examples of disorders easily identified by physical examination that could significantly affect diagnosis and operative risk in a patient with transient cerebral ischemia. Auscultation of the lungs and palpation of the abdomen are essential in the setting of metastatic spine disease. Emphysema, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pleural effusion, extensive atelectasis, and ascites have an impact on anesthetic risk and may influence patient positioning and surgical approach. Gallbladder disease may refer pain to the back or scapula and may be mistaken for cervical radiculopathy. Nephrolithiasis or ureterolithiasis is often mistaken for a lumbar radiculopathy and may be screened for by gentle percussion over the lumbar paraspinal musculature. Examination of peripheral pulses and distal skin integrity is important in patients with diabetes and possible vascular claudication.

Components of the Neurologic Examination

Inspection

Posture

Inspection of the spinal column as a single unit should be performed from both a lateral and posterior viewpoint in standing and forward bending positions. Abnormalities in spinal balance in both the sagittal and coronal planes can be pathologic and have important implications when considering surgical deformity correction. Asymmetry of paravertebral muscles, spinous processes, skin creases, shoulders, scapulae, and hips may be appreciated in patients with scoliosis.3 Coronal imbalance can be assessed clinically by examining the standing patient from behind and measuring the distance between a plumb line dropped from C7 and the gluteal cleft. Sagittal imbalance may be implied when a patient stoops forward when walking or sitting. It is best determined by a plumb line from C7 to the sacrum on lateral radiographs.4 A compensatory forward rocking of the pelvis and flexion of the knees while standing may be seen in severe cases. The recognition of sagittal imbalance is paramount to precise surgical planning, especially when planning for deformity correction.

Gait Analysis

Other Characteristic Gaits

Patients suffering from compression of neural elements of the lumbosacral spine often show characteristics of “antalgic gait.” This term is somewhat nonspecific but involves alteration of the movement of the affected extremity in an attempt to silence the pain generator. Lumbar radiculopathy associated with weakness of several different muscles can alter gait. Weakness of ankle dorsiflexors and foot drop may cause a patient to walk with a “steppage gait.” To clear the ground while the patient pushes off, the hip is flexed excessively and the foot may slap the ground. Weakness of gluteus medius (L5) hip abduction or gluteus maximus (S1) hip extension may cause the patient to rock the thorax, or “waddle,” to compensate for poor hip fixation. Patients with advanced lumbar stenosis and neurogenic claudication tend to walk in a flexed-forward position, commonly referred to as the “anthropoid posture.” The spinal surgeon should keep psychiatric disorders on his or her list of differential diagnoses when assessing gait. Gait and posture disturbances are the presenting symptom in up to 10% of patients with psychogenic disorders such as anxiety and depression.5

Palpation and Range of Motion Testing of the Spine and Related Areas

Cervical Spine

In the cervical spine, the resting head position is noted before evaluation of ROM. A patient with a fixed rotation or tilt to one side may have an underlying unilateral facet dislocation. Although precise quantitative evaluation of ROM is not typically performed, the clinician should note obvious limitations and which maneuvers generate pain. Pain or restricted rotation of the head, 50% of which occurs at C1-2, 6 may indicate a pathologic process at this level. Head rotation associated with vertigo, tinnitus, visual alterations, or facial pain may be nonspecific, but occlusion of the vertebral artery should be included in the differential. Selecki7 showed that rotation of the head more than 45 degrees could significantly kink the contralateral vertebral artery. Extension and rotation of the head can exacerbate pre-existing nerve root compression, and flexion in the setting of cord compression often causes paresthesia in both the arms and legs (Lhermitte sign).

Thoracic Spine

Examination of the thoracic spine should focus on the detection of scoliosis or a kyphotic deformity. The patient is observed from behind for symmetry in the level of the shoulders, scapulae, and hips. If a scoliotic deformity is noticed on inspection, flexion and lateral bending are assessed to further characterize the curve and determine its flexibility. Asymmetry in the paravertebral musculature with forward flexion can generate an angle in the horizontal plane that can be followed for progression. In the upper thoracic spine, there are 4 degrees of sagittal plane rotation, 6 degrees of lateral bending, and 8 to 9 degrees of axial rotation at each segment. In the lower two to three segments, these median figures are 12 degrees, 8 to 9 degrees, and 2 degrees, respectively.6

Motor Examination

Muscle weakness is frequently seen in patients suffering from compression of specific nerve roots or the spinal cord itself. Weakness may be the patient’s primary symptom or discovered only after physical examination. Motor deficits may be acute and rapidly progressive (i.e., after traumatic disc herniation) or more insidious in onset, similar to the setting of cervical myelopathy. A detailed motor examination and muscle grading (Table 12-1) of the key muscles innervated by the cervical and lumbar nerve roots should be performed in every patient. Evaluating strength systematically allows the clinician to identify common patterns of muscle weakness seen in cord compression and brachial plexus syndromes and reduces the likelihood of missing nonsurgical pathology.

| Grade | Description |

|---|---|

| 0 | No palpable/visible contraction |

| 1 | Muscle flicker |

| 2 | Movement with gravity eliminated |

| 3 | Movement against gravity with full range of motion |

| 4 | Movement against gravity and some resistance |

| 5 | Movement against full resistance |

Cervical Spine

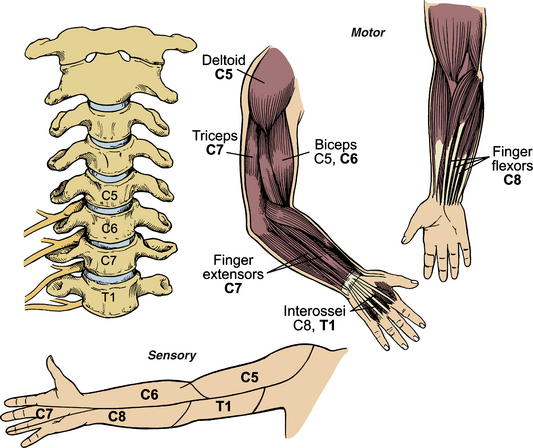

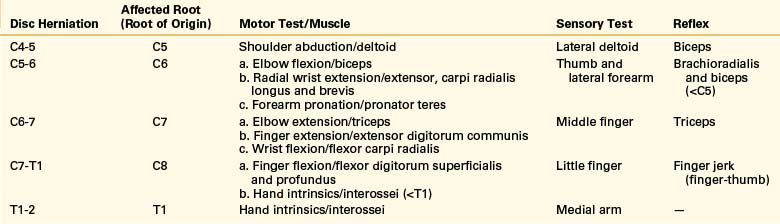

Figure 12-1 and Table 12-2 summarize the motor tests used to grade muscle strength for the cervical nerve roots that contribute to motor function of the upper extremity. It is important to remember that the configuration of the brachial plexus (prefixed or postfixed) can alter the typical pattern of innervation by one level. The anatomic relationship of the cervical vertebrae and motor roots must be kept in mind when attempting to correlate motor deficits to nerve root compression seen on an MRI or myelogram. A C5-6 disc herniation, for example, typically compresses the origin of the C6 root before it exits the neural foramen above the C6 pedicle. It has recently been demonstrated that forearm pronation weakness is the most frequent motor abnormality in C6 radiculopathy.8 Such evidence illustrates the necessity of a detailed motor examination.

Lumbar Spine

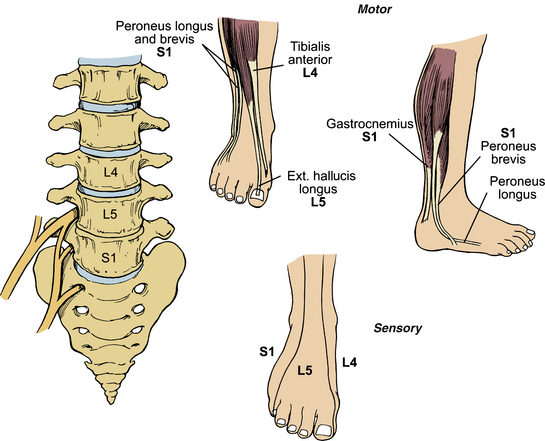

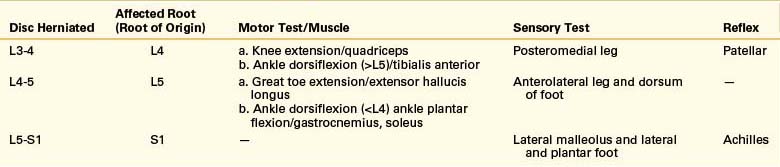

Figure 12-2 and Table 12-3 summarize the motor tests used to grade muscle strength for the lumbar nerve roots commonly affected in clinical practice. Again, correlating clinical findings with radiographic abnormalities is imperative. With a typical paracentral L4-5 disc herniation, for example, the root of origin (L5) is compressed as it courses toward the undersurface of the L5 pedicle. A far lateral disc herniation at the same level may compress the root of exit (L4). Detecting motor deficits in the lower extremity, particularly in a large, muscular patient, can occasionally be difficult. Testing the patient’s ability to heel (tibialis anterior) and toe (gastrocnemius) walk, maneuvers that require a patient to overcome body weight, can uncover a subtle weakness.

Sensory Examination

The key sensory dermatomes of the upper and lower extremities are depicted in Figures 12-1 and 12-2. The nipple line (T4) and umbilicus (T10) are useful thoracic landmarks. It is emphasized, however, that these landmarks are variable. Of particular note is that the T2 dermatome may be as low as the nipple line, and that it demarcates the C4 to T2 dermatome junction. The clinician should always compare dermatomes from one side with the other and ask the patient to quantify differences. Both light touch and pain perception should be tested, and proprioception and vibratory sense should be included in patients suspected of having cord compression, peripheral nerve entrapment, or sensory neuropathy. The sensory examination is particularly critical in the evaluation of the spinal cord-injured patient to determine the level of injury and to monitor for a progressing deficit. A rectal examination should usually be performed to assess for sphincter tone and perianal dermatomes. Preservation of perianal sensation in the presence of a discrete sensory level defines an incomplete lesion and may dramatically affect management and prognosis for recovery. Special mention should be made here of provocative sensory tests for nerve entrapment syndromes that can occasionally be confused with cervical radiculopathy. Median nerve compression (C6) in the carpal tunnel, ulnar nerve entrapment (C8) in the cubital tunnel or Guyon canal, and radial nerve compression (C7) in the forearm are important differential diagnoses and occasionally coexist with root compression in the neck, the “double crush phenomenon.”9 Tapping on the nerve proximal to the site of compression can reproduce symptoms (Tinel sign) in the middle course of nerve root compression while the nerve is attempting to regenerate. Sustained wrist flexion over 60 seconds can produce signs of median nerve compression (Phalen sign), and similar testing can be done by flexing the elbow (ulnar nerve compression) or pronating the forearm (radial nerve compression).

Reflex Examination

Deep Tendon Reflexes

The deep tendon reflexes are used to assess the integrity of a monosynaptic reflex arc at various levels of the cord. Table 12-4 depicts the common system for grading deep tendon reflexes. Hyperactive reflexes generally indicate an upper motor neuron lesion, and diminished or absent reflexes can be seen in lower motor neuron lesions. Metabolic abnormalities, such as hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism, should always be excluded as an etiology for abnormal reflexes. Neuromuscular disorders and neuropathies may also present with abnormal reflexes. Reflexes are compared from one side to another, and reinforcement maneuvers that require isometric contraction of other muscle groups can be used to eliminate cortical modulation of the reflex arc. The Jendrassik maneuver can accentuate lower extremity reflexes and requires the patient to pull interlocked fingers apart while the reflex is tested. Asking the patient to clench the teeth or push down on the examination table with the thighs can accentuate upper extremity reflexes.

| Grade | Description |

|---|---|

| 0 | No response |

| 1 | Diminished |

| 2 | Normal |

| 3 | Increased |

| 4 | Hyperactive (with clonus) |

One uncommonly practiced reflex is the finger jerk or finger-thumb reflex. Mediated by mainly the C8 nerve root, it is elicited with patient’s palm upturned and the fingers half-flexed. The surgeon then holds the tops of the fingers with his or her own half-flexed fingers, which are then tapped. The patient’s fingers will be felt to flex and, most strikingly, the free thumb will be seen to flex.10 Although the commonly tested reflexes are truly mediated by multiple nerve roots, Tables 12-2 and 12-3 outline the dominant nerve roots involved.

Superficial Reflexes

The superficial reflexes are mediated by the cerebral cortex with the afferent limb being supplied by cutaneous stimulation. The absence of a normal cutaneous reflex may signal an underlying upper motor neuron lesion. In the thoracic spine, the upper abdominal (T8-9), mid-abdominal (T9-10), and lower abdominal (T11-12) superficial reflexes can be used to assess the integrity of motor efferents from these levels.10 As the appropriate dermatome is stroked from lateral to medial, the ipsilateral abdominal muscles will contract. In a thin, muscular patient the examiner will occasionally observe movement of the umbilicus toward the stimulated side. In the lumbar spine, the superficial cremasteric reflex is mediated by L1 and L2. Stimulating the upper medial thigh in a male patient will cause elevation of the testicle on the ipsilateral side. The anocutaneous reflex, or “anal wink,” is used to assess S2 through S4 and involves contraction of the external anal sphincter in response to stimulation of the perianal skin. The importance of testing this reflex in the setting of spinal cord injury has been previously mentioned.

Pathologic Reflexes

The upper extremity analogue of the plantar response is the Hoffmann sign. The palmar surface of the hand is lightly supported as the patient’s middle finger is flicked into extension or flexion at the distal interphalangeal joint. A positive response involves reflex flexion of the thumb and fingers and is commonly observed in myelopathic patients with cervical spinal cord compression. A recent study11 of 536 patients with spine-related problems found 16 patients with a positive Hoffmann sign and no pain or neurologic symptoms referable to the cervical spine. Interestingly, 15 (94%) of these patients had some degree of cord compression on cervical MRI. The clinical significance of this study is unclear, however, because prior studies12 have documented cervical cord impingement in up to 20% of asymptomatic adults older than 40 years of age.

Provocative Nerve Root Testing

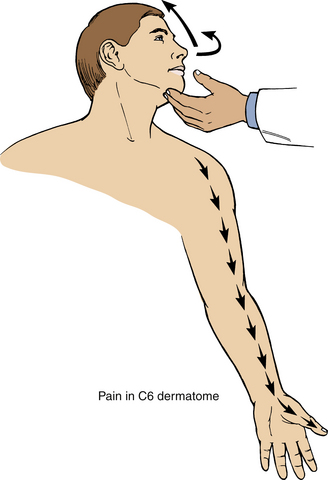

Cervical Spine

Patients with cervical radiculopathy often complain of worsening pain with Valsalva activities or when rotating the head toward the symptomatic extremity. A foraminal closing test (Fig. 12-3) is performed by hyperextending the patient’s head and rotating it toward the affected side, thus decreasing the size of the intervertebral foramen. An axial load is then often applied by pressing down on the patient’s head. A positive test reproduces the patient’s radicular symptoms and is often referred to as the Spurling sign. A recent review of the Spurling test,13 which was administered before electromyelographic testing of 255 patients referred for possible cervical radiculopathy, found poor sensitivity (30%) but excellent specificity (93%). Similar maneuvers can be used to reproduce radicular symptoms, including pure axial compression followed by traction, but these tend to be poorly tolerated by patients. Patients with cervical radiculopathy may also get relief by placing the affected extremity behind the head (the shoulder abduction relief sign).14

Lumbar Spine

There are several well-described nerve root tension signs that are useful when testing for lumbar radiculopathy.15

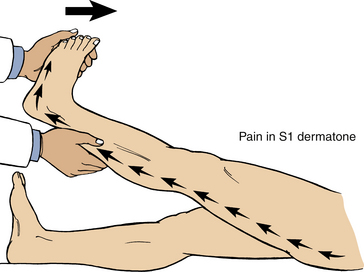

Straight Leg Raising Test (Lasègue Sign)

The most widely used test to differentiate leg pain resulting from hip pathology versus nerve root irritation is the straight leg raising test (SLR). The test was discovered by the French pathologist Ernest Charles Lasègue16 and described in 1881 by one of his pupils, J. J. Forst. In the supine position, the patient’s fully extended leg is slowly raised and the patient reports any pain that is elicited. The SLR is considered positive if pain or paresthesia occurs in a radicular distribution at less than 60 degrees of elevation (Fig. 12-4). Lowering the affected leg and dorsiflexing the ankle will exacerbate the pain. Allowing the foot to rest on the examining table by flexing the knee will typically ease the pain (bowstring sign). Pain limited to the low back, hip, or posterior thigh is not indicative of a radiculopathy. SLR is most specific for L5 or S1 radiculopathy.

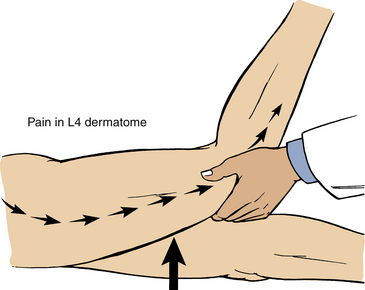

Reverse Straight Leg Raising Test (Femoral Stretch Test)

This test is more sensitive for pain caused by radiculopathy involving L2, L3, and L4. In the prone or lateral decubitus position, the patient’s knee is maximally flexed as the hip is extended (Fig. 12-5). A positive test involves pain in the distribution of the affected nerve root.

Crossed Straight Leg Raising Test (Well Leg/Straight Leg Raising Test)

The crossed straight leg raising test (CSLR) is performed by raising the unaffected leg with the patient in the supine position and is positive when radicular pain occurs in the clinically affected extremity. This phenomenon is also referred to as the Fajersztajn sign, in honor of the Polish neurologist who first described it17 and, interestingly, also suggested that foot dorsiflexion would aggravate sciatica. The test is typically positive when the patient has a large central disc herniation. It is more specific but less sensitive than SLR.18 A meta-analysis done by Devillé et al. demonstrated that SLR is 91% sensitive and 26% specific, whereas CSLR is 29% sensitive and 88% specific.19

Differentiating Spinal Cord and Peripheral Nerve Pathology from Bony or Soft Tissue Pathology

Cervical Radiculopathy versus Upper Extremity Pathology

Shoulder

Patients often present with cervical radiculopathy complaints that also include pain or tenderness of the shoulder joint. Possible causes of shoulder pain include bicipital tendon subluxation, frozen shoulder syndrome, and shoulder dislocation. The Yergason test consists of externally rotating the humerus against resistance with the patient’s elbow flexed. Resulting pain suggests an unstable biceps tendon. The drop arm test is a quick test for a rotator cuff tear. The patient’s arm is abducted to 90 degrees by the examiner and is dropped. If the patient can hold the arm steady, the rotator cuff is likely normal. A rotator cuff injury is possible if the arm falls and the patient is unable to slowly lower it to his or her side. The apprehension test aids in the diagnosis of chronic shoulder dislocation. The arm is abducted and externally rotated. If the shoulder joint is about to dislocate, the patient may exhibit a look of apprehension or fear.20

Elbow

Lateral epicondylitis or tennis elbow is a common condition that may be confused with cervical radiculopathy owing to weakness of the forearm extensors. Patients with lateral epicondylitis experience exquisite pain at the insertion of the wrist extensor’s origin when asked to dorsiflex the involved wrist against resistance.20

Boden D.S., McGowin P.R., Davis D.O., et al. Abnormal magnetic-resonance scans of the cervical spine in asymptomatic subjects. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1990;72:1178-1183.

Chabrol H., Corraze J. Charles Lasègue, 1809-1863. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:28.

Devillé W.L., van der Windt D.A., Dzaferagić A., et al. The test of Lasègue: systematic review of the accuracy in diagnosing herniated discs. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25:1140-1147.

Glassman S.D., Bridwell K., Dimar J.R., et al. The impact of positive sagittal balance in adult spinal deformity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 30, 2005. 2204–2029

Rainville J., Noto D.J., Jouve C., et al. Assessment of forearm pronation strength in C6 and C7 radiculopathies. Spine. 2007;32(1):72-75.

Sung R.D., Wang J.C. Correlation between a positive Hoffmann’s reflex and cervical pathology in asymptomatic individuals. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26:67-70.

White A.A.III, Panjabi M.M. Basic biomechanics of the spine. Neurosurgery. 1980;7:76-93.

1. Mastroianni P.P., Roberts M.P. Femoral neuropathy and retroperitoneal hemorrhage. Neurosurgery. 1983;13:44-47.

2. Glassman S.D., Anagnost S.C., et al. The effect of cigarette smoking and smoking cessation on spinal fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25:2608-2615.

3. Dickson J.H., Erwin W.D., Esses S.I. Spinal deformity. In: Esses S.I., editor. Textbook of spinal disorders. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1995:257-286.

4. Glassman S.D., Bridwell K., Dimar J.R., et al. The impact of positive sagittal balance in adult spinal deformity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 30, 2005. 2204–2029

5. Sudarsky L. Psychogenic gait disorders. Semin Neurol. 2006;26:351-356.

6. White A.A.III, Panjabi M.M. Basic biomechanics of the spine. Neurosurgery. 1980;7:76-93.

7. Selecki B.R. The effects of rotation of the atlas and axis: experimental work. Med J Aust. 1969;1:1012-1015.

8. Rainville J., Noto D.J., Jouve C., et al. Assessment of forearm pronation strength in C6 and C7 radiculopathies. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32(1):72-75.

9. Upton A.R.M., McComas A.J. The double crush in nerve entrapment syndromes. Lancet. 1973;2:359-362.

10. LeBlond R., DeGowin R., Brown D. DeGowin’s diagnostic examination, ed 8. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2004. pp 809–810

11. Sung R.D., Wang J.C. Correlation between a positive Hoffmann’s reflex and cervical pathology in asymptomatic individuals. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26:67-70.

12. Boden D.S., McGowin P.R., Davis D.O., et al. Abnormal magnetic-resonance scans of the cervical spine in asymptomatic subjects. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1990;72:1178-1183.

13. Tong H.C., Haig A.J., Yamakawa K. The Spurling test and cervical radiculopathy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27:156-159.

14. Davidson R.I., Dunn E.J., Metzmaker J.N. The shoulder abduction test in the diagnosis of radicular pain in cervical extradural compressive monoradiculopathies. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1981;6:441-446.

15. Scham S.M., Taylor T.K.F. Tension signs in lumbar disc prolapse. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1971;75:195-204.

16. Chabrol H., Corraze J. Charles Lasègue, 1809-1863. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:28.

17. Karbowski K. History of the discovery of the Lasègue phenomenon and its variants. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1984;114:992-995.

18. Hudgins W.R. The crossed straight leg raising test: a diagnostic sign of herniated disc. J Occup Med. 1979;6:407-408.

19. Devillé W.L., van der Windt DA, Dzaferagić A., et al. The test of Lasègue: systematic review of the accuracy in diagnosing herniated discs. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25:1140-1147.

20. Hoppenfeld S. Chapter 1. Physical examination of the shoulder. Chapter 2. Physical examination of the elbow. In: Hoppenfeld S., editor. Physical examination of the spine and extremities. Norwalk, CT: Appleton & Lange; 1976:1-57.