29 Pharynx and Throat Emergencies

• Viruses cause most cases of pharyngitis, but the modified Centor score represents a scoring system that can increase detection of group A β-hemolytic streptococcal pharyngitis.

• Consider corticosteroids in patients with pharyngitis for symptomatic relief of tonsillar hypertrophy.

• Unilateral pain and swelling may indicate peritonsillar abscess (consider ultrasound).

• Consider epiglottitis in circumstances in which the findings on physical examination do not match the patient’s pain and other symptoms. Visualize the epiglottis to rule out the disease.

• Ludwig angina is characterized by bilateral submandibular swelling, fever, and an elevated or protruding tongue.

• Lemierre syndrome, a suppurative thrombophlebitis located within the internal jugular vein, is a complication of nearby infections in the pharynx or mastoid space.

• Retropharyngeal abscesses in children younger than 6 years are due to infected lymph nodes and in adults are due to local or hematogenous spread. They require imaging to make the diagnosis because examination findings are notoriously unreliable in this population.

Acute Pharyngitis and Tonsillitis

Pathophysiology

Viruses cause most cases of pharyngitis. Even the most common cause of bacterial pharyngitis in children, group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus (GAβHS), is responsible for only 30% of cases of pharyngitis. In adults, Streptococcus species account for 23% of cases, with Mycoplasma (9%) and Chlamydia (8%) species also being significant.1 Recently, Fusobacterium necrophorum, known to be a factor in Lemierre syndrome, has been show to be a causal agent in as many as 10% of cases of pharyngitis in young adults.2

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Viral

![]() Documentation

Documentation

Visualization of the airway, including patients with suspected epiglottitis or supraglottitis

Work of breathing and use of accessory muscles

Patient’s ability to take fluids by mouth

Discussion (and understanding) with the patient and family of the need for close observation and what symptoms to return for arranged follow-up

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

Bacterial

Rapid diagnostic testing for GAβHS detects antigens via varying techniques, including latex agglutination, enzyme-linked or optical immunoassay, and DNA luminescent probes. Specificities are reported to be greater than 90% with sensitivities between 60% and 95%.3 A positive test appears to be a reliable indicator of the presence of GAβHS in the pharynx, but a number of factors must be considered. Some patients with a positive test may be asymptomatic carriers, and rapid tests may be negative in patients with low bacterial counts.

In addition to cultures and rapid streptococcal tests, a number of authors have proposed clinical criteria to aid in the diagnosis of GAβHS pharyngitis. The most well known are the Centor criteria and the McIssac modifications of these criteria. The modified Centor score gives one point each to temperature higher than 38° C, swollen tender anterior cervical nodes, tonsillar swelling or exudates, absence of upper respiratory tract symptoms (e.g., cough, coryza), and age between 3 and 15 years. If the patient is older than 45 years, a point is subtracted. If the score is 1 or less, no further testing or treatment is warranted. For scores of 2 to 3, further testing may be indicated, such as cultures or rapid streptococcal tests. For scores of 4 or higher, no further testing is required and all patients may receive antibiotics for GAβHS pharyngitis (Box 29.1).4,5

Box 29.1 Clinical Diagnosis of Streptococcal Pharyngitis

In two recent guidelines (from the Infectious Diseases Society of America [IDSA] and the American Society of Internal Medicine [ASIM]), slightly different approaches to patients with pharyngitis have been proposed. In children the guidelines are similar and call for the use of a rapid test in all children; those with a positive test are treated, those with a negative test undergo a throat culture, and those with a positive culture result are treated. The guidelines have suggested different approaches to adults with pharyngitis, however. The IDSA guidelines propose treating all adults in a fashion similar to their pediatric recommendations.6 The ASIM guidelines, though, allow two additional approaches for adults, including performing a rapid test on all adults with a Centor score of 2 or 3 and treating those with a positive test result, as well as empirically treating all patients with a score of 4 or higher. The final approach endorsed by the ASIM suggests testing no adults but treating all adults with a Centor score of 3 or 4 empirically.7 A recent analysis comparing the different recommendations found that an approach using throat cultures had a sensitivity of 100%; approaches using rapid treptococcal tests involving clinical criteria alone had sensitivities of approximately 75%. Furthermore, the specificity of clinical criteria alone was below 50%, thus suggesting that many adults were prescribed antibiotics for pharyngitis unnecessarily.8

Peritonsillitis, Peritonsillar Cellulitis, and Abscess

Diagnostic Testing

Plain radiographs do not aid in the diagnosis or treatment of uncomplicated cases of peritonsillitis. Although it is often difficult to distinguish peritonsillar cellulitis from peritonsillar abscess,9 a number of modalities can aid in diagnosis. For patients who cannot lie down or who are unable to cooperate with needle aspiration, intraoral ultrasound is a useful test.10 Computed tomography (CT) is helpful in delineating the extent and scope of the abscess, but it may be difficult for the patient to lie supine during the study.

Treatment

Pending airway obstruction requires emergency aspiration of a peritonsillar abscess. For less urgent conditions the classic recommendation was incision and drainage. Needle aspiration, with or without ultrasound guidance, provides a diagnosis, induces less pain, and is easier to perform than traditional incision and drainage. Approximately 10% of needle-aspirated abscesses require repeated aspiration.9

Epiglottitis and Supraglottitis

Epidemiology and Pathophysiology

Inflammation and edema of the epiglottis may result in rapid and life-threatening airway obstruction if not identified and treated effectively. In addition, the tissues immediately adjacent to the epiglottis (arytenoids, false vocal cords, and pharyngeal wall) may also become edematous and result in a similar infection known as supraglottitis. The signs and symptoms of the two diseases may be remarkably similar, although their populations may be somewhat different. Until introduction of the Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib) vaccine in the mid-1980s, epiglottitis was a disease of children. The annual incidence decreased dramatically to a very low 0.3 to 0.6 per 100,000 children.11 Adult epiglottitis appears to be on the rise. One study showed a 31% rise in the incidence of adult epiglottitis over an 18-year period.12 Incidence rates for adults cluster near 3 per 100,000, with a case fatality rate reported to be as high as 7%. The lower overall bacteremia rates in adults than in children suggest that adults may have more viral causes, as well as other noninfectious causes. Noninfectious causes include trauma, ingestion of caustic substances, or thermal injuries from illicit drug inhalation. Of organisms recovered in blood cultures, Hib still predominates, but Streptococcus and Staphylococcus species may be isolated as well.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Children

Epiglottitis in children produces a dramatic progression from a relatively well child to a toxic-appearing one. Eighty-five percent of patients are sick for less than 24 hours. Affected children appear anxious, may be sitting forward in a tripod position, and may have difficult clearing secretions (Table 29.1).

Table 29.1 Symptoms of Epiglottitis or Supraglottitis in Children

| SYMPTOM | FREQUENCY (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| AGE < 2 yr | AGE > 2 yr, < 18 yr | |

| Fever | 100 | 99 |

| Difficulty breathing | 97 | 94 |

| Irritability | 89 | 94 |

| Change in voice or cry | 82 | 96 |

| Stridor | 92 | 88 |

| Retractions | 88 | 78 |

Adults

Adults with epiglottitis have a mean age of between 42 and 50 years. Unlike children, adults are usually seen after 2 to 3 days of symptoms. Adults exhibit odynophagia and throat pain rather than the drooling and stridor of pediatric patients. This difference is thought to be due to the larger and more rigid trachea and lack of generous lymph tissue in adults. The pharyngeal pain may be disproportionate to the clinical findings. Fever is frequently absent in adults until the later stages. Additionally, epiglottitis or supraglottitis is frequently misdiagnosed in adults as streptococcal pharyngitis, only to have the true diagnosis made later (Table 29.2).

Table 29.2 Symptoms of Epiglottitis or Supraglottitis in Adults

| SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS | FREQUENCY (%) |

|---|---|

| Muffled voice | 54-79 |

| Pharyngitis | 57-73 |

| Fever | 54-70 |

| Anterior neck tenderness | 79 |

| Dyspnea | 29-37 |

| Drooling | 22-39 |

| Stridor | 12-27 |

Medical Decision Making

A lateral radiograph of patients with suspected epiglottitis has high sensitivity approaching 90% when compared with direct laryngoscopy. Findings on a lateral radiograph may include an edematous and thickened epiglottis (thumb shaped) (Fig. 29.1), disappearance of the vallecula, swelling of the epiglottic folds or arytenoids, or edema of the retropharyngeal spaces. Adults with normal radiographic findings and suspected epiglottitis must undergo laryngoscopy, either direct or indirect. In no pediatric patients should an attempt be made to visualize the epiglottis in the ED. Pediatric patients should be taken to the operating room for direct laryngoscopy while surgical staff members are present to obtain a surgical airway, if needed.

Ludwig Angina

Epidemiology and Pathophysiology

First described in 1836, Ludwig angina is a fast-spreading, potentially lethal infection of the submandibular, sublingual, and submental spaces. These spaces effectively function as one unit, and infection can easily spread between them. True Ludwig angina involves all of the submandibular spaces; however, serious and life-threatening infections can occur with infection of only some of the spaces. Before the advent of antibiotics and surgical decompression, mortality with this disease approached 50%, but it is now commonly reported to be less than 10%.13

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Physical findings in almost all patients include bilateral submandibular swelling, fever, and an elevated or protruding tongue (Figs. 29.2 through 29.4). Trismus is found in approximately half of all patients. Complications of Ludwig angina can be disastrous, with infection spreading to the mediastinum, pericardium, or pleural cavity, as well as the lungs and great vessels.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

![]() Priority Actions

Priority Actions

Move patients with potential airway compromise to code rooms.

Prepare for an emergency airway procedure:

In pediatric patients with possible epiglottitis, laryngoscopy should not be attempted until personnel skilled in emergency airway techniques are present.

Initiate antibiotic therapy early in patients with serious infections.

Perform appropriate imaging of patients for serious infections such as retropharyngeal abscess or supraglottitis when their pain is out of proportion to the findings on examination.

Diagnostic Testing

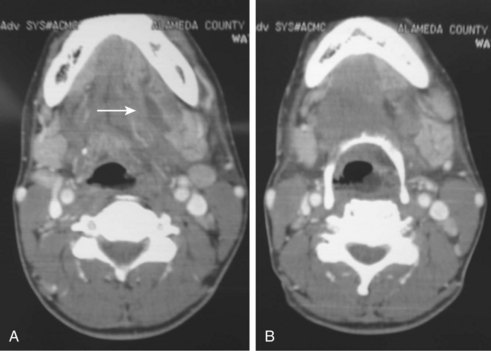

Because Ludwig angina is predominantly a clinical diagnosis, diagnostic testing commonly delineates the extent of infection, not whether it is present. Soft tissue lateral neck radiographs may be helpful in showing edema of the soft tissues and air in the soft tissue spaces. If the patient is able to lie supine for a short while, helical CT may be helpful in delineating progression of the abscess and allow more accurate surgical débridement (Fig. 29.5, A and B). If the safety of the patient lying supine is at all in question, the airway must be secured first. At all times the utmost caution is required in these patients, and securing the airway will probably involve the joint capabilities of anesthesia, otorhinolaryngologic, and general surgical colleagues. No airway maneuvers may be attempted until the equipment and personnel capable of obtaining a surgical airway are present at the bedside.

Lemierre Syndrome

Pathophysiology

Lemierre syndrome is often caused by the organism F. necrophorum, a gram-negative anaerobe that produces endotoxin and is also responsible for many cases of acute and recurring pharyngitis, as well as peritonsillar abscesses.14 F. necrophorum can colonize the upper respiratory, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary tracts. Other organisms that may also cause this particular variant of septic thrombophlebitis include Bacteroides melaninogenicus, Eikenella corrodens, and non–group A streptococci.

Retropharyngeal Abscess

Pathophysiology

The cause of retropharyngeal abscesses in the nonpediatric population differs greatly from the local lymph node infections in the age group younger than 6 years. The cause of adult retropharyngeal abscesses ranges from extension of other pharyngeal infections (e.g., parotitis, peritonsillar abscess, tonsillitis, Ludwig angina, dental infections) to instrumentation and other trauma (fishbones or dental instruments) to hematologic spread of systemic infections.15

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Patients will have a sore throat, as well as any number of other symptoms, including dysphagia, drooling, odynophagia, neck pain, and a muffled voice. The dysphonia frequently sounds like a duck quack (cri du canard). Patients may complain of a feeling of a lump in their throat and may prefer to lie supine or with their neck extended to keep the swelling in their posterior pharynx from compressing their upper airway. In the pediatric population, many case series have reported the mean age as being 3 years. It is uncommon for children in this age group to describe these symptoms, and the more common complaints are related to feeding, fever, and stridor.16

On physical examination only a minority of adult patients (37%) will have visible swelling of the posterior pharynx.17 Other physical findings might include cervical lymphadenopathy, torticollis, and trismus. Palpation of the neck or moving the larynx and trachea side to side (tracheal “rock” sign) may induce pain. Pain and other symptoms out of proportion to the findings on physical examination require further diagnostic testing and evaluation.

Diagnostic Testing

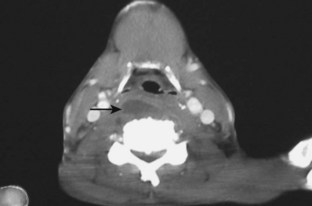

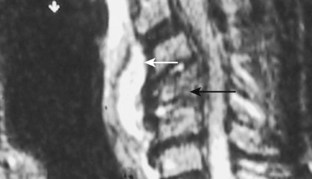

Imaging of retropharyngeal abscesses involves two main types of radiologic tests, plain lateral neck radiographs and CT scans. Early studies of normal lateral radiographs suggest that the upper limit of normal for the retropharyngeal spaces is 7 mm at C2 and 22 mm at C6. Anything beyond 7 mm is considered pathologic in both children and adults. In addition, retropharyngeal abscesses will displace the larynx and esophagus anteriorly. If there is still a question about the extent of involvement or the distinction between cellulitis and abscess, CT of the neck (Fig. 29.6) or MRI (Fig. 29.7) will easily elucidate the exact anatomic extension of the abscess. Of course, patients must be stable enough to lie flat in the supine position for the time needed to complete the study. In addition, intraoral ultrasound is another modality with great potential for distinguishing between abscess and cellulitis.18

Treatment and Disposition

Retropharyngeal infections require broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics. The antibiotics must cover anaerobes, as well as gram-positive and gram-negative species. Although most retropharyngeal abscesses require surgical drainage, selected cases may occasionally be managed with intravenous antibiotics alone.19 Even if surgical drainage is deferred, admission to a monitored bed after thorough airway evaluation is required.

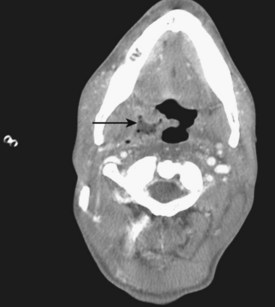

Complications from retropharyngeal abscesses include spread of infection inferiorly or laterally (Fig. 29.8) into the mediastinum (Fig. 29.9), pericardium, and nearby vascular structures. Osteomyelitis (see Fig. 29.7), transverse myelitis, and epidural abscesses have also been reported.

Fig. 29.8 Computed tomography scan of a retropharyngeal abscess (arrow) extending laterally and inferiorly.

![]() Red Flags

Red Flags

Do not miss the diagnosis of acute epiglottitis or supraglottitis. It is more sudden in children than in adults.

Do not give ampicillin to patients with suspected infectious mononucleosis because an uncomfortable rash develops.

Do not miss abscesses. Use ultrasonography or computed tomography to diagnose peritonsillar abscesess. Retropharyngeal abscesses are difficult to diagnose unless considered and imaged.

When the pharyngeal pain is out of proportion to the findings on physical examination, exclude more serious causes such as epiglottitis and deep space infections.

Aliyu SH, Marriott RK, Curran MD, et al. Real-time PCR investigation into the importance of Fusobacterium necrophorum as a cause of acute pharyngitis in general practice. J Med Microbiol. 2004;53:1029–1035.

Bisno AL. Acute pharyngitis. N Engl J. Med 2001;344:205–211.

Frantz TD, Rasgon BM. Acute epiglottitis: changing epidemiologic patterns. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1993;109:457–460.

Lyon M, Blaivas M. Intraoral ultrasound in the diagnosis and treatment of suspected peritonsillar abscess in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:85–88.

Spires JR, Owens JJ, Woodson GE, et al. Treatment of peritonsillar abscess. A prospective study of aspiration vs incision and drainage. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1987;113:984–986.

1 Bisno AL. Acute pharyngitis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:205–211.

2 Aliyu SH, Marriott RK, Curran MD, et al. Real-time PCR investigation into the importance of Fusobacterium necrophorum as a cause of acute pharyngitis in general practice. J Med Microbiol. 2004;53:1029–1035.

3 Bisno AL, Gerber MA, Gwaltney Jr, JM., et al. Diagnosis and management of group A streptococcal pharyngitis: a practice guideline. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:574–583.

4 Centor RM, Witherspoon JM, Dalton HP, et al. The diagnosis of strep throat in adults in the emergency room. Med Decis Making. 1981;1:239–246.

5 McIsaac WJ, White D, Tannenbaum D, et al. A clinical score to reduce unnecessary antibiotic use in patients with sore throat. CMAJ. 1998;158:75–83.

6 Bisno AL, Gerber MA, Gwaltney JM, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of group A streptococcal pharyngitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:113–125.

7 Cooper RJ, Hoffman JR, Bartlett JG, et al. Principles of appropriate antibiotic use for acute pharyngitis in adults: background. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:509–517.

8 McIsaac WJ, Kellner JD, Aufricht P, et al. Empirical validation of guidelines for the management of pharyngitis in children and adults. JAMA. 2004;291:1587–1595.

9 Spires JR, Owens JJ, Woodson GE, et al. Treatment of peritonsillar abscess. A prospective study of aspiration vs incision and drainage. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1987;113:984–986.

10 Lyon M, Blaivas M. Intraoral ultrasound in the diagnosis and treatment of suspected peritonsillar abscess in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:85–88.

11 Frantz TD, Rasgon BM. Acute epiglottitis: changing epidemiologic patterns. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1993;109:457–460.

12 Mayo-Smith MF, Spinale JW, Donskey CJ, et al. Acute epiglottitis. An 18-year experience in Rhode Island. Chest. 1995;108:1640–1647.

13 Bansal A, Miskoff J, Lis RJ. Otolaryngologic critical care. Crit Care Clin. 2003;19:55–72.

14 Klug TE, Rusan M, Fuursted K, et al. Fusobacterium necrophorum: most prevalent pathogen in peritonsillar abscess in Denmark. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1467–1472.

15 Goldenberg D, Golz A, Joachims HZ. Retropharyngeal abscess: a clinical review. J Laryngol Otol. 1997;111:546–550.

16 Thompson JW, Cohen SR, Reddix P. Retropharyngeal abscess in children: a retrospective and historical analysis. Laryngoscope. 1988;98:589–592.

17 Tannebaum RD. Adult retropharyngeal abscess: a case report and review of the literature. J Emerg Med. 1996;14:147–158.

18 Ben-Ami T, Yousefzadeh DK, Aramburo MJ. Pre-suppurative phase of retropharyngeal infection: contribution of ultrasonography in the diagnosis and treatment. Pediatr Radiol. 1990;21:23–26.

19 Craig FW, Schunk JE. Retropharyngeal abscess in children: clinical presentation, utility of imaging, and current management. Pediatrics. 2003;111:1394–1398.