Chapter 2 Pharmacognosy and its history

people, plants and natural products

Sources of information

The sources available for understanding the history of medicinal (as well as nutritional and toxic) plant use are archaeological records and written documents. The desire to summarize information for future generations and to present the writings of the classical (mostly early Greek) scholars to a wider audience was the major stimulus for writing about medicinal plants. The traditions of Japan, India and China were also documented in many early manuscripts and books (Mazar 1998, Waller 1998). No written records are available for other regions of the world either because they were never produced (e.g. Australia, many parts of Africa and South America, and some regions of Asia) or because documents were lost or destroyed by (especially European) invaders (e.g. in Meso-America). Therefore, for many parts of the world the first written records are reports by early travellers who were sent by their respective feudal governments to explore the wealth of the New World. These people included missionaries, explorers, salesmen, researchers and, later, colonial officers. The information was important to European societies for reasons of potential dangers, such as poisoned arrows posing a threat to explorers and settlers, as well as the prospect of finding new medicines.

Early Arabic and European records

An early European example is medicinal mushrooms, which were found with the Austrian/Italian ‘iceman’ of the Alps of Ötztal (3300 BCE). Two walnut-sized objects were identified as the birch polypore (Piptoporus betulinus), a bracket fungus common in alpine and other cooler environments. This species contains toxic natural products, and one of its active constituents (agaric acid) is a very strong and effective purgative, which leads to strong and short-lasting diarrhoea. It also has antibiotic effects against mycobacteria and toxic effects on diverse organisms (Capasso 1998). Since the iceman also harboured eggs of the whipworm (Trichuris trichiuria) in his gut, he may well have suffered from gastrointestinal cramps and anaemia. The finding of Piptoporus betulinus points to the possible treatment of gastrointestinal problems using these mushrooms. Also, scarred cuts on the skin of the iceman might indicate the use of medicinal plants, since the burning of herbs over an incision on the skin was a frequent practice in many ancient European cultures (Capasso 1998).

The earliest documented record, which presumably relates to medicinal (or ritual) plants, dates from 60,000 BCE in the grave of a Neanderthal man from Shanidar IV, an archaeological site in Iraq. Pollen of several species of plants was discovered (Leroi-Gourhan 1975, Solecki 1975, Lietava 1992):

Centaurea solstitialis L. (knapweed, Asteraceae)

Ephedra altissima (ephedra, Ephedraceae)

Achillea sp. (yarrow, Asteraceae)

Althea sp. (mallow, Malvaceae)

Classical Arabic, Greek and Roman records

Greek medicine has been the focus of historical pharmaceutical research for many decades. The Greek scholar Pedanius Dioscorides (Fig. 2.1) from Anarzabos (1 BC) is considered to be the ‘father of [Western] medicine’. His works were a doctrine governing pharmaceutical and medical practice for more than 1500 years, and which heavily influenced European pharmacy. He was an excellent pharmacognosist and described more than 600 medicinal plants. Other Greek and Roman scholars were also influential in developing related fields of health care and the natural sciences. Hippocrates, a Greek medical doctor (ca. 460–375 BC) came from the island of Kos, and heavily influenced European medical traditions. He was the first of a series of (otherwise largely unknown) authors who produced the so-called Corpus Hippocraticum (a collection of works on medical practice). The Graeco-Roman medical doctor Claudius Galen (Galenus) (130–201 AD) summarized the complex body of Graeco-Roman pharmacy and medicine, and his name survives in the pharmaceutical term ‘galenical’. Pliny the Elder (23 or 24–79 AD, killed in Pompeii at the eruption of Vesuvius) was the first to produce a ‘cosmography’ (a detailed account) of natural history, which included cosmology, mineralogy, botany, zoology and medicinal products derived from plants and animals.

Classical Chinese records

Written documents about medicinal plants are essential elements of many cultures of Asia. In China, India, Japan and Indonesia, writings pointing to a long tradition of plant use survive. In China, the field developed as an element of Taoist thought: followers tried to assure a long life (or immortality) through meditation, special diets, medicinal plants, exercise and specific sexual practices. The most important work in this tradition is the Shen nong ben caojing (the ‘Drug treatise of the divine countryman’) which is now only available as part of later compilations (Waller 1998; see also Chapter 12, p. 177 et seq). This 2200-year-old work includes 365 drugs, most of botanical origin. For each, the following information is provided:

These scholarly ideas were passed on from master to student, and modified and adapted over centuries of use. Unfortunately, in none of the cases do we have a surviving written record. Table 2.1 summarizes some of the Chinese works that include important chapters on drugs.

Table 2.1 Chinese works that include important sections on drugs (after Waller 1998)

| Year | Author if known | Title |

|---|---|---|

| 200 BC | Shen Nong | Shen nong ben cao jing (the drug treatise of the divine countryman) |

| 2nd century | Shang han za bing lun (about the various illnesses caused by cold damage) | |

| 6th century | Tao Hongjing | Shen nong ben cao jing fi zhu (collected commentaries on Shen nong ben cao jing) |

| 10th to 12th centuries | Ben cao tu jing | |

| 16th century | Li Shizhen | Ben cao gang mu (information about medicinal drugs: a monographic treatment) |

| 1746 | Jing shi zheng lei bei ji ben cao |

In the 16th century the first systematic treatise on (herbal) drugs using a scientific method was produced. The Ben Cao Gang Mu (‘Drugs’, by Li Shizhen, 1518–1593) contains information about 1892 drugs (in 52 chapters) and more than 11,000 recipes are given in an appendix. The drugs are classified into 16 categories (e.g. herbs, cereals, vegetables, fruits). For each drug the following information is provided (Waller 1998):

Other Asian traditional medicine

Ayurveda

Ayurveda is arguably one of the most ancient of all recorded medicinal traditions. It is considered to be the origin of systemized medicine, because ancient Hindu writings on medicine contain no references to foreign medicine whereas Greek and Middle Eastern texts do refer to ideas and drugs of Indian origin. Dioscorides (who influenced Hippocrates) is thought to have taken many of his ideas from India, so it looks as though the first comprehensive medical knowledge originated there. The term ‘Ayurveda’ comes from ayur meaning ‘life’ and veda meaning ‘knowledge’ and is a later addition to Hindu sacred writing from 1200 BC called the Artharva-veda. The first school to teach Ayurvedic medicine was at the University of Banaras in 500 BC and the great Samhita (or encyclopaedia of medicine) was written. Seven hundred years later another great encyclopaedia was written and these two together form the basis of Ayurveda. The living and the non-living environment, including humans, is composed of the elements earth (prithvi), water (jala), fire (tejac), air (vaju) and space (akasa). For an understanding of these traditions, the concept of impurity and cleansing is also essential. Illness is the consequence of imbalance between the various elements and it is the goal of treatment to restore this balance (see Chapter 12 for details).

Jamu

The status of Jamu started to improve ca. 1940 with the Second Congress of Indonesian Physicians, at which it was decided that an in-depth study of traditional medicine was needed. A further impetus was the Japanese occupation of 1942–1944, when the Dai Nippon government set up the Indonesian Traditional Medicines Committee; another boost occurred during Indonesia’s War of Independence when orthodox medicine was in short supply. President Sukarno decreed that the nation should be self-supporting, so many people turned to the traditional remedies used by their ancestors (see Beers 2001).

Kampo

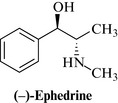

In 1184 the framework began to change when a reformed system was introduced by Yorimoto Minamoto in which native medicine was included, and by 1574 Dosan Manase had set down all the elements of medical thought which became a form of independent Japanese medicine during the Edo period. This resulted in Kampo, and it remained the main form of medicine until the introduction of Western medicine in 1771, by Genpaku Sugita. Although Sugita did not reject Kampo, and advocated its use in his textbook book Keieiyawa, it fell into decline because of a lack of evidence and an increasingly scholastic rather than empirical approach to treatment. Towards the end of the 19th century, despite important events such as the isolation of ephedrine (Fig. 2.2) by Nagayoshi Nagai, Kampo was still largely ignored by the Japanese medical establishment. However, by 1940, a university course on Kampo had been instituted, and now most schools of medicine in Japan offer courses on traditional medicine integrated with Western medicine. In 1983, it was estimated that about 40% of Japanese clinicians were writing Kampo herbal prescriptions and today’s research in Japan and Korea continues to confirm the validity of many of its remedies (Takemi et al 1985).

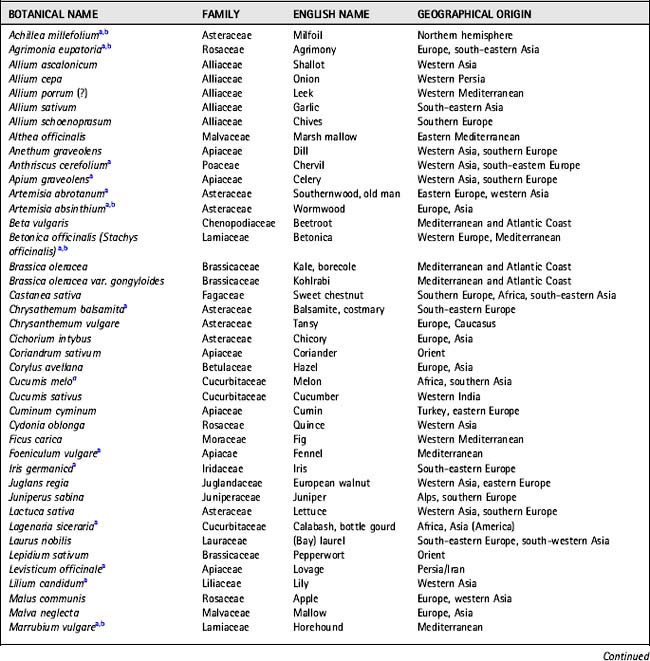

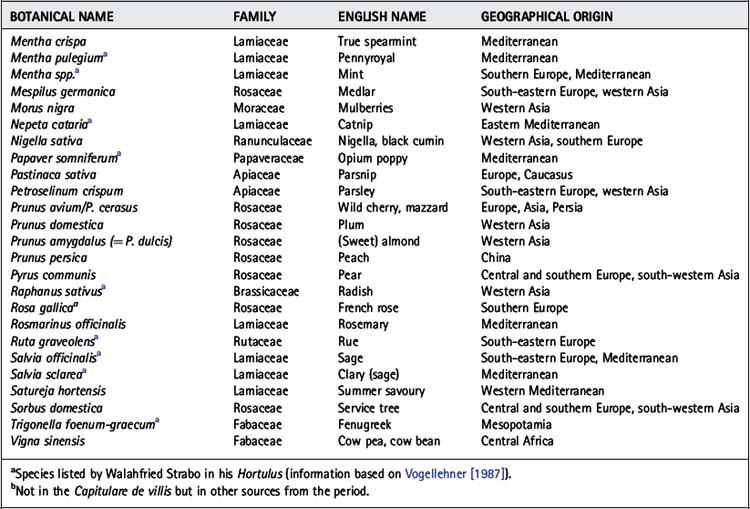

The European Middle Ages and Arabia

A common element of all monasteries was a medicinal plant garden, which was used both for growing herbs to treat patients and for teaching about medicinal plants to the younger generation. The species included in these gardens were common to most monasteries and many of the species are still important medicinal plants today. Of particular interest is the Capitulare de villis of Charles the Great (Charlemagne, 747–814), who ordered that medicinal (and other plants) should be grown in the King’s gardens and in monasteries, and specifically listed 24 species. Walahfri(e)d Strabo (808 or 809–849), Abbot of the monastery of Reichenau (Lake Constance), deserves mention because of his Liber de cultura hortum (‘Book on the growing of plants’), the first ‘textbook’ on (medical) botany, and the Hortulus, a Latin poem about the medical plants grown in the district. The Hortulus is not only famous as a piece of poetry, but also because of its vivid and excellent descriptions of the appearance and virtues of medicinal plants. Table 2.2 lists the plants reported in the Capitulare de villis and in some other sources of the 10th and 11th centuries. Today, many of these plants are still important medicinally or in other ways. Many are vegetables, fruits or other foods. The list shows not only the long tradition of medicinal plant use in Europe, but also the importance of these resources to the state and religious powers during the Middle Ages. Although these were not necessarily of interest as scholarly writings, they were at least a practical resource.

Printed reports in the European tradition (16th century)

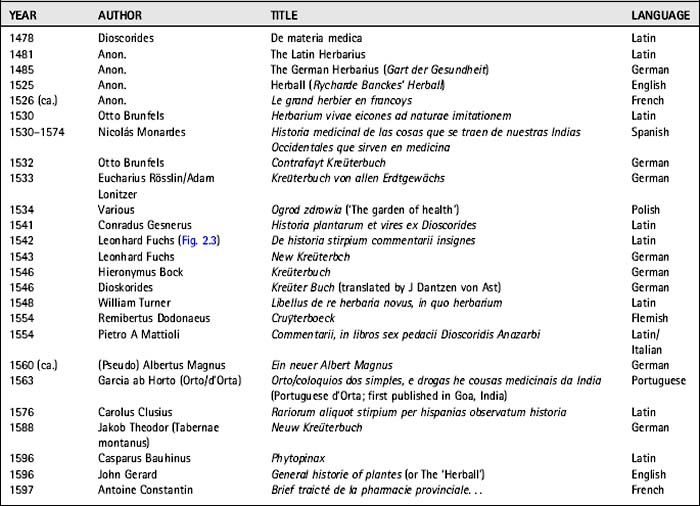

For over 1500 years the classical and most influential book in Europe had been Dioscorides’ De materia medica. Until the Europeans’ (re-)invention of printing in the mid-15th century (by Gutenberg), texts were hand-written codices, which were used almost exclusively by the clergy and scholars in monasteries. A wider distribution of the information on medicinal plants in Europe began with the early herbals, which rapidly became very popular and which made the information about medicinal plants available in the languages of lay people. These were still strongly influenced by Graeco-Roman concepts, but influences from many other sources came in during the 16th century (see Table 2.3).

Table 2.3 Examples of early European herbals from the 15th and 16th centuries (based on Leibrock-Plehn 1992 and Arber 1938)

Herbals were rapidly becoming available in various European languages and, in fact, many later authors copied, translated and re-interpreted the earlier books. This was especially so for the woodcuts used for illustration (see Fig. 2.4); these were often used in several editions or were copied. The herbals changed the role of European pharmacy and medicine and influenced contemporary orally transmitted popular medicine. Previously there had been two lines of practice: the herbal traditions of the monasteries and the popular tradition, which remains practically unknown. Books in European languages made scholastic information much more widely available and it seems that the literate population was eager to learn about these medicopharmaceutical practices. These new books became the driving force of European ‘phytotherapy’, which developed rapidly over the next centuries.

Another development was the establishment of independent guilds specializing in the sale of medicinal plants, even though apothecaries had practised this for centuries. In 1617, the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries was founded in London, and in 1673 it formed its own garden of medicinal plants, known today as the Chelsea Physic Garden (Minter 2000). One of the most well-known English apothecaries (and astrologers) of the 17th century is Nicholas Culpeper (1616–1654), best known for his ‘English physician’ – more commonly called ‘Culpeper’s herbal’. This is the only herbal that rivals in popularity John Gerard’s General historie of plantes, but his arrogant dismissal of orthodox practitioners made him very unpopular with many physicians. Culpeper describes plants that grow in Britain and which can be used to cure a person or to ‘preserve one’s body in health’. He is also known for his translation A physicall directory (from Latin into English) of the London Pharmacopoeia of 1618 published in 1649 (Arber 1938).

Medical herbalism

The use of medicinal plants was always an important part of the medical systems of the world, and Europe was no exception. Little is known about popular traditions in medieval and early modern Europe and our knowledge starts with the availability of written (printed) records on medicinal plant use by common people. As pointed out by Griggs (1981, p. 88), a woman in the 17th century was a ‘superwoman’ capable of administering ‘any wholesome receipts or medicines for the good of the family’s health’. A typical example of such a remedy is foxglove (Digitalis purpurea), reportedly used by an English housewife to treat dropsy, and then more systematically by the physician William Withering (1741–1799; Fig. 2.5). Withering transformed the orally transmitted knowledge of British herbalism into a form of medicine that could be used by medical doctors. Prior to that, herbalism was more of a clinical practice interested in the patient’s welfare, and less of a systematic study of the virtues and chemical properties of medicinal plants.

European pharmacognosy and natural product chemistry in the 18th and 19th centuries

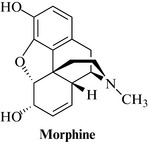

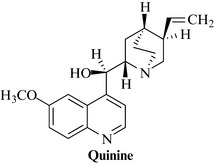

• morphine (Fig. 2.6) from opium poppy (Papaver somniferum, Papaveraceae), which was first identified by FW Sertürner of Germany (Fig. 2.7) in 1804 and chemically characterized in 1817 as an alkaloid. The full structure was established in 1923, by JM Gulland and R Robinson, in Manchester

• quinine (Fig. 2.8), from cinchona bark (Cinchona succirubra and others), was first isolated by Pierre Joseph Pelletier and Joseph Bienaime Caventou of France in 1820; the structure was elucidated in the 1880s by various laboratories. Pelletier and Caventou were also instrumental in isolating many of the alkaloids mentioned below

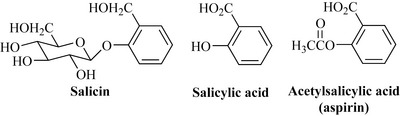

• salicin, from willow bark (Salix spp., Salicaceae), was first isolated by Johannes Buchner in Germany. It was derivatized first (in 1838) by Rafaele Pirea (France) to yield salicylic acid, and later (1899) by the Bayer company, to yield acetylsalicylic acid, or aspirin – a compound that was previously known but which had not been exploited pharmaceutically (Fig. 2.9).

Fig. 2.7 FW Sertürner.

Reproduced with permission from The Wood Library-Museum of Anesthesiology, Park Ridge, IL, London.

Examples of pure compounds isolated during the early 19th century

Atropine (1833), from belladonna (Atropa belladonna, Solanaceae), was used at the time for asthma.

Strychnine (1817), from Strychnos spp. (Loganiaceae), was used as a tonic and stimulant

One of the main achievements of 19th century science in the field of medicinal plants was the development of methods to study the pharmacological effects of compounds and extracts. The French physiologist Claude Bernard (1813–1878), who conducted detailed studies on the pharmacological effects of plant extracts, must be considered one of the first scientists in this tradition. He was particularly interested in curare – a drug and arrow poison used by the American Indians of the Amazon, and the focus of research of many explorers. The ethnobotanical story of curare is described further in Chapter 5.

Bernard noted that, if curare was administered into living tissue directly, via an arrow or a poisoned instrument, it resulted in death more quickly, and that death occurred more rapidly if dissolved curare was used rather than the dried toxin (Bernard 1966: 95–96). He was also able to demonstrate that the main cause of death was by muscular paralysis, and that animals showed no signs of nervousness or pain. Further investigations showed that, if the blood flow in the hind leg of a frog was interrupted using a ligature (without affecting the innervation) and the curare was introduced via an injury of that limb, the limb retained mobility and the animal did not die [Bernard 1966:95–96, 115 (orig. 1864)]. One of the facts noted by all those who reported on curare is the lack of toxicity of the poison in the gastrointestinal tract, and, indeed, the Indians used curare both as a poison and as a remedy for the stomach.

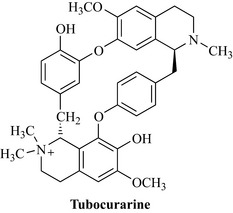

Later, the botanical source of curare was identified as Chondrodendron tomentosum Ruiz et Pavon, and the agent largely responsible for the pharmacological activity first isolated. It was found to be an alkaloid, and named D-tubocurarine because of its source, ‘tube curare’, so-called because of the bamboo tubes used as storage containers. In 1947 the structure of this complex alkaloid, a bisbenzylisoquinoline, was finally established (Fig. 2.10). The story of this poison is one of the most fascinating examples of transforming a drug used in an indigenous culture into a medication and research tool, and, although D-tubocurarine is now used less frequently for muscular relaxation during surgery, it has been used as a template for the development of newer and better drugs.

The 20th century

One of the most important events that influenced the use of medicinal plants in the Western world in the last century was the serendipitous discovery of the antibacterial properties of fungal metabolites such as benzylpenicillin, by Florey and Fleming in 1928 at St Mary’s Hospital (London). These natural products changed forever the perception and use of plant-derived metabolites as medicines by both scientists and the lay public. Another important development came with the advent of synthetic chemistry in the field of pharmacy. Many of these studies involved compounds that were synthesized because of their potential as colouring material (Sneader 1996). The first successful use of a synthetic compound as a chemotherapeutic agent was achieved by Paul Ehrlich in Germany (1854–1915); he successfully used methylene blue in the treatment of mild forms of malaria in 1891. Unfortunately, this finding could not be extended to the more severe forms of malaria common in the tropics. Many further studies on the therapeutic properties of dyes and of other synthetic compounds followed.

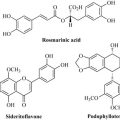

The latter part of the 20th century saw a rapid expansion in knowledge of secondary natural products, their biosynthesis, and their biological and pharmacological effects. A large number of natural products or their derivatives were introduced as medicines, including many anti-cancer agents (paclitaxol, the vinca alkaloids; see Chapter 6, pp. 103), the anti-malarial agent artemisinin and the anti-dementia medication galanthamine, to name just a few (Cragg et al 2005, Heinrich 2010, Heinrich & Teoh 2004). Numerous examples of drugs which are natural products, their deriviates or a pharmacophore based on a natural product have been introduced. There is now a better understanding of the genetic basis of the reactions that give rise to such compounds, as well as the biochemical (and in many cases genetic) basis of many important illnesses. This has opened up new opportunities and avenues for drug development.

Arber A. Herbals. In Their origin and evolution. A chapter in the history of botany 1470–1670. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1938.

Bernard C. Physiologische Untersuchungen über einige amerikanische Gifte. Das Curare. (orig. French 1864). Bernard C., Mani N., editors. Ausgewählte physiologische Schriften. 1966:84-133. Huber Verlag, Bern

Bernard C. Physiologische Untersuchungen über einigeamerikanische Gifte. Das Curare. (frz. orig. 1864). Bernard C., und N., Mani. (Übs.) Ausgewählte physiologische Schriften. 1966:84-133. Huber Verlag. Bern

Beers S.-J. Jamu. In The ancient art of Indonesian herbal healing. Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd, Singapore Burger A, Wachter H 1998 Hunnius pharmazeutisches Wörterbuch, 8 Aufl. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter; 2001.

Capasso L. 5300 years ago, the ice man used natural laxatives and antibiotics. Lancet. 1998;352:1894.

Cragg G.M., Newman D.J. Plants as a source of anti-cancer agents. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005;100:72-79.

Griggs B. Green pharmacy. London: A history of herbal medicine. Norman & Hobhouse; 1981.

Heinrich M. Ethnopharmacology and drug development. In: Mander L., Lui H.W., editors. Comprehensive natural products II Chemistry and biology, vol. 3. Oxford: Elsevier; 2010:351-381.

Heinrich M., Teoh H.L. Galanthamine from snowdrop – the development of a modern drug against Alzheimer’s disease from local Caucasian knowledge. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2004;92:147-162.

Leibrock-Plehn L. Hexenkräuter oder Arznei: die Abtreibungsmittel im 16 und 17 Jahrhundert. In Heidelberger Schriften zur Pharmazie- und Naturwissenschaftsgeschichte, Bd 6. Stuttgart: Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft; 1992.

Leroi-Gourhan A. The flowers found with Shanidar IV, a Neanderthal burial in Iraq. Science. 1975;190:562-564.

Lietava J. Medicinal plants in a Middle Paleolithic grave Shanidar IV. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 1992;35:263-266.

Mazar G. Ayurvedische Phytotherapie in Indien. Z. Physiother.. 1998;19:269-274.

Minter S. The Apothecaries’ Garden. Stroud: Sutton Publications; 2000.

Solecki R.S. Shanidar IV, a Neanderthal flower burial in Northern Iraq. Science. 1975;190:880-881.

Sneader W. Drug prototypes and their exploitation. Chichester: Wiley; 1996.

Sommer J.D. The Shanidar IV ‘flower burial’: a re-evaluation of Neanderthal burial ritual. Cambridge Archaeological Journal. 1999;9(1):127-137.

Takemi T., Hasegawa M., Kumagai A., Otsuka Y. Herbal medicine: Kampo, past and present. Tokyo: Tsumura Juntendo Inc.; 1985.

Vogellehner D. Jardines et verges en Europe occidentale (VIII–XVIII siècles). Flaran. 1987;9:11-40.

Waller F. Phytotherapie der traditionellen chinesischen Medizin. Z. Physiother.. 1998;19:77-89.

Adams M., Caroline Berset C., Kessler M., Hamburger M. Medicinal herbs for the treatment of rheumatic disorders—A survey of European herbals from the 16th and 17th century. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2009;121:343-359.

von Humboldt A., Beck H, Hrsg. Die Forschungsreise in den Tropen Amerikas [Studienausgabe Bd 2, Teilband 3]. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchsgesellschaft; 1997.