Chapter 28 Pervasive Developmental Disorders and Childhood Psychosis

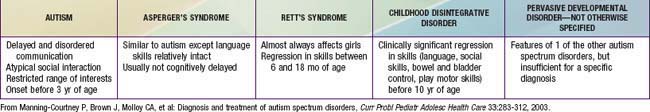

The pervasive developmental disorders (PDD) and childhood schizophrenia can be understood as disturbances of brain development with genetic underpinnings. PDD spectrum includes autistic, Asperger’s, childhood disintegrative, Rett’s, and PDD not otherwise specified (NOS) disorders. Children with these disorders all share the inability to attain expected social, communication, emotional, cognitive, and adaptive abilities (Table 28-1).

28.1 Autistic Disorder

Clinical Manifestations

The core features of autistic disorder (AD) include impairments in 3 symptom domains: social interaction; communication; and developmentally appropriate behavior, interests, or activities (Table 28-2). Stereotypical body movements, a marked need for sameness, and a very narrow range of interests are also common.

Table 28-2 DSM-IV-TR DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR AUTISTIC DISORDER

From American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision, Washington, DC, 2000, American Psychiatric Association.

Diagnosis

The medical and genetic evaluation of children with PDD must consider a broad range of disorders (Table 28-3). Approximately 20% of children with AD have macrocephaly, but enlarged head size might not be apparent until after the 2nd yr of life. In the absence of dysmorphic features or focal neurologic signs, additional neuroimaging for investigation of macrocephaly is not usually indicated. Multidisciplinary assessment of AD is optimal in facilitating early diagnosis, treatment, and coordinated multiagency collaboration. Evaluations from various other professionals, including a developmental pediatrician or pediatric neurologist, medical geneticist, child and adolescent psychiatrist, speech-language pathologist, occupational or physical therapist, or medical social worker may be indicated.

Table 28-3 MEDICAL AND GENETIC EVALUATION OF CHILDREN WITH PERVASIVE DEVELOPMENTAL DISORDERS

REQUIRED EVALUATIONS

CONSIDER IF RESULTS OF ABOVE EVALUATIONS ARE NORMAL, AND IN CHILDREN WITH COMORBID MENTAL RETARDATION

METABOLIC TESTING TO CONSIDER BASED ON OTHER CLINICAL FEATURES

OTHER TESTING TO CONSIDER BASED ON CLINICAL FEATURES

ELECTROENCEPHALOGRAPHY IF THE FOLLOWING CLINICAL FEATURES ARE NOTED

From Barbaresi WJ, Katusic SK, Voigt R: Autism: a review of the state of the science for pediatric primary care clinicians, Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 160:1169, 2006.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes consideration of the various PDD, mental retardation not associated with PDD (Chapter 33), specific developmental disorders (e.g., of language), early onset psychosis (e.g., schizophrenia), selective mutism, social anxiety (Chapter 23), obsessive-compulsive disorder, stereotypic movement disorder, inhibited-type reactive attachment disorder, and rarely, childhood-onset dementia.

Early Identification

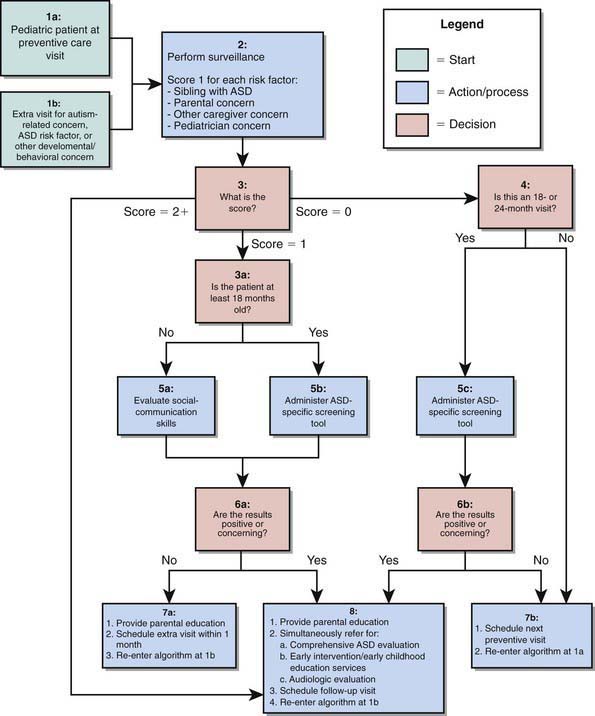

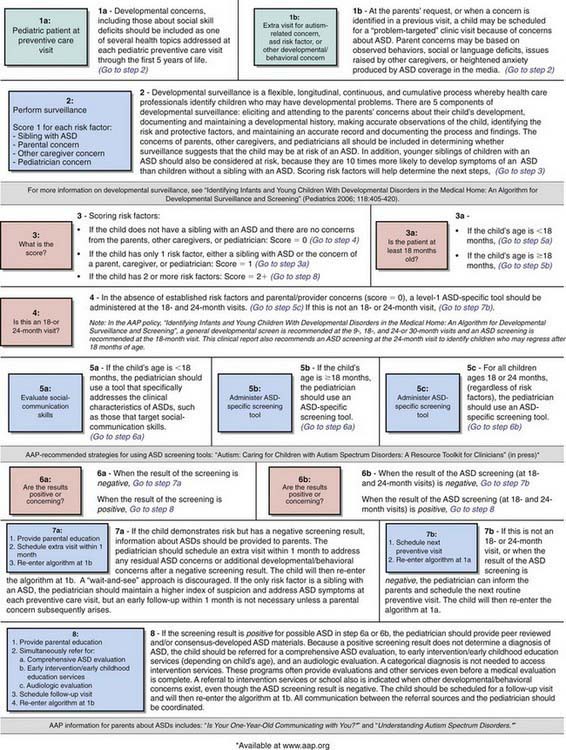

Early identification and intervention of PDD are associated with better outcomes. Several instruments have been developed for screening of PDD in primary care settings including the Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (CHAT), the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT), and the Pervasive Developmental Disorders Screening Test (PDDST) (Chapter 18) (Fig. 28-1). Failures to meet age-expected language or social milestones are important early red flags for PDD and should prompt an immediate evaluation. Early signs include unusual use of language or loss of language skills, nonfunctional rituals, inability to adapt to new settings, lack of imitation, and absence of imaginary play. Deviations in social and emotional development (such as decreased eye contact, failure to orient to name, and lack of joint attention) can often be detected by 1 yr of age. The absence of expected social, communication, and play behavior often precedes the emergence of odd or stereotypical behaviors or the unusual language usage that is seen in AD in the later years.

Treatment

Model early childhood educational programs for children with PDD can be categorized as behavior analytic, developmental, or structured teaching on the basis of the underlying theoretical orientation. Although programs differ in relative emphasis, they share many common goals, including beginning intervention as early as possible; providing intensive intervention (at least 25 hr/wk, 12 mo/yr) in systematically planned educational activities; providing a low student-to-teacher ratio; including parent training; promoting opportunities for interaction with typically developing peers incorporating a high degree of structure through elements such as a predictable routine, visual activity schedules, and clear physical boundaries; implementing strategies to apply learned skills to new environments and situations; and using curricula that address functional spontaneous communication, social skills, functional adaptive skills, reduction of maladaptive behaviors, cognitive skills, and traditional academic skills. Some well-regarded programs that address at least some of these skills include Applied Behavioral Analysis (ABA), Discrete Trial Training (DTT), and Treatment and Education of Autistic and related Communication-handicapped Children (TEACCH). Most educational programs available to young children with PDDs are based in communities in the context of an Individualized Education Program (Chapter 15), and offer an eclectic treatment approach, which may be less effective than standardized protocols.

Pharmacotherapy can increase the ability of persons with AD to benefit from educational and other interventions and to remain in less-restrictive environments (Table 28-4). Common targets for pharmacological intervention include associated comorbid conditions and problematic behaviors such as aggression, self-injurious behavior, hyperactivity, inattention, anxiety, mood lability, irritability, compulsive-like behaviors, stereotypic behaviors, and sleep disturbances. After treatable medical causes and modifiable environmental factors have been ruled out, a trial of medication may be considered if the behavioral symptoms cause significant impairment in functioning. Prescribing is best approached with consultation from a practitioner with background and training in developmental disabilities.

Table 28-4 SELECTED POTENTIAL MEDICATION OPTIONS FOR COMMON TARGET SYMPTOMS OR COEXISTING DIAGNOSIS IN CHILDREN WITH AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDERS

| TARGET SYMPTOM CLUSTERS | POTENTIAL COEXISTING DIAGNOSES | SELECTED MEDICATION CONSIDERATIONS |

|---|---|---|

| Repetitive behavior, behavioral rigidity, obsessive-compulsive symptoms | Obsessive-compulsive disorder, stereotypic movement disorder |

SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Modified from Myers SM, Plauche Johnson C, Council on Children with Disabilities: Management of children with autism spectrum disorders, Pediatrics 120:1162-1182, 2007.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors appear to have efficacy for the treatment of co-occurring mood and anxiety symptoms and compulsive-like behaviors among persons with AD. Of the typical antipsychotics, haloperidol has evidence supporting a role in reducing stereotypy and facilitating learning. There has been concern about its use given the high rates of dyskinesias that are incurred. Given a more favorable side-effect profile in this population, atypical neuroleptics have been increasingly used with demonstrated efficacy on the symptoms of agitation, irritability, aggression, self-injury, and severe temper outbursts (Table 28-5; Chapter 19). Risperidone and aripiprazole have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treating irritability associated with autism. In moderate doses, stimulants can benefit children with hyperactivity and impulsivity. α-Adrenergic agonists can reduce hyperarousal symptoms including hyperactivity, irritability, impulsivity, and repetitive behavior. The evidence for mood stabilizers in AD is limited.

Table 28-5 DSM-IV-TR DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR ASPERGER’S DISORDER

From American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision, Washington, DC, 2000, American Psychiatric Association.

Allison C, Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S, et al. The Q-CHAT (Quantitative Checklist for Autism in Toddlers): a normally distributed quantitative measure of autistic traits at 18-24 months of age: preliminary report. J Autism Dev Disord. 2008;38:1414-1425.

Amaral D, Schuman C, Nordhal C. Neuroanatomy of autism. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31:137-145.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, ed 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry: Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children, adolescents, and adults with autism and other pervasive developmental disorders, J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, in press.

Bandini LG, Anderson SE, Curtin C, et al. Food selectivity in children with autism spectrum disorders and typically developing children. J Pediatr. 2010;157:259-264.

Barbaresi WJ, Katusic SK, Voigt R. Autism: a review of the state of the science for pediatric primary care clinicians. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:1167-1175.

Chen CY, Chen KH, Liu CYL, et al. Increased risk of congenital, neurologic, and endocrine disorders associated with autism in preschool children: cognitive ability differences. J Pediatr. 2009;154:345-350.

Constantino JN, Zhang Y, Frazier T, et al. Sibling recurrence and the genetic epidemiology of autism. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(11):1349-1356.

Ecker C, Marguand A, Mourao-Miranda J, et al. Describing the brain in autism in five dimensions—magnetic resonance imaging–assisted diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder using a multiparameter classification approach. J Neurosci. 2010;30(32):10612-10623.

Giulivi C, Zhang YF, Omanska-Klusek A, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in autism. JAMA. 2010;304(21):2389-2396.

Johnson S, Marlow N. Positive screening: results on the modified checklist for autism in toddlers: implications for very preterm populations. J Pediatr. 2009;154:478-480.

Jones W, Carr K, Klin A. Absence of preferential looking to the eyes of approaching adults predicts level of social disability in 2-year-old toddlers with autism spectrum disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:946-954.

Mandell DS, Wiggins LD, Armstein Carpenter L, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in the identification of children with autism spectrum disorders. Am J Pub Health. 2009;99:493-498.

Marshall CR, Noor A, Vincent JB, et al. Structural variation of chromosomes in autism spectrum disorder. Am J Human Genetics. 2008;82:1-12.

Morrow EM, Yoo SY, Flavell SW, et al. Identifying autism loci and genes by tracing recent shared ancestry. Science. 2008;321:218-223.

Myers SM, Plauche Johnson C, Council on Children with Disabilities. Management of children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2007;120:1162-1182.

Ozonoff S, Losif AM, Baguio F, et al. A prospective study of the emergence of early behavioral signs of autism. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(3):256-266.

Plauche Johnson C, Myers SM, Council on Children with Disabilities. Identification and evaluation of children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2007;120:1183-1215.

Rapoport J, Chavez A, Greenstein D, et al. Autism spectrum disorders and childhood-onset schizophrenia: clinical and biological contributions to a relation revisited. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48:10-16.

Schendel D, Karapurkar Bhasin T. Birth weight and gestational age characteristics of children with autism, including a comparison with other developmental disabilities. Pediatrics. 2008;121:1155-1164.

Weiss LA, Shen Y, Korn JM, et al. Association between microdeletion and microduplication at 16p11.2 and autism. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:667-675.

28.2 Asperger’s Disorder

Children with Asperger’s disorder have a qualitative impairment in the development of reciprocal social interaction. They often show repetitive behaviors with restricted, obsessional, and idiosyncratic interests. To meet the DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for Asperger’s disorder, a child must manifest impairments in social interactions and show restrictive, repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, or achievements with other people. These disturbances must cause significant impairments in social or occupational functioning (see Table 28-5).

Although they are somewhat socially aware, these children appear to others to be peculiar or eccentric. They can be awkward and clumsy and have unusual postures and gait. There are often similar traits in family members. This disorder might represent a form of high-functioning AD (children with autism without cognitive impairment), although this distinction remains controversial. Group social skills training is an effective intervention. CBT has been useful in patients with associated anxiety, and risperidone can improve negative symptoms similar to those seen in schizophrenia. Because children with Asperger’s disorder are at high risk for other psychiatric disorders, particularly mood (Chapter 24) and anxiety disorders (Chapter 23) screening for such problems is an important part of the evaluation.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, ed 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry: Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children, adolescents, and adults with autism and other pervasive developmental disorders, J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, in press.

Jones W, Carr K, Klin A. Absence of preferential looking to the eyes of approaching adults predicts level of social disability in 2-year-old toddlers with autism spectrum disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:946-954.

Myers SM, Plauche Johnson C, Council on Children with Disabilities. Management of children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2007;120:1162-1182.

Plauche Johnson C, Myers SM, Council on Children with Disabilities. Identification and evaluation of children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2007;120:1183-1215.

Toth K, King B. Asperger’s syndrome: diagnosis and treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:958-963.

28.3 Childhood Disintegrative Disorder

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, ed 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry: Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children, adolescents, and adults with autism and other pervasive developmental disorders, J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, in press.

Myers SM, Plauche Johnson C, Council on Children with Disabilities. Management of children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2007;120:1162-1182.

Plauche Johnson C, Myers SM, Council on Children with Disabilities. Identification and evaluation of children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2007;120:1183-1215.

28.4 Childhood Schizophrenia

The signs and symptoms of schizophrenia in children are classified in the DSM-IV-TR into 2 broad domains of positive and negative symptoms (see Table 28-6 on the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics website at www.expertconsult.com ![]() ). Positive symptoms include hallucinations, delusions, disorganized speech, and/or disorganized or catatonic behavior. Negative symptoms include flattening of affect, social withdrawal, loss of motivation, and cognitive impairments. These latter symptoms are related to poorer premorbid functioning and an increased familial risk of schizophrenia. Children with schizophrenia have more-severe premorbid neurodevelopmental abnormalities, increased cytogenetic anomalies, and stronger family histories of psychotic disorders in comparison to their adult counterparts.

). Positive symptoms include hallucinations, delusions, disorganized speech, and/or disorganized or catatonic behavior. Negative symptoms include flattening of affect, social withdrawal, loss of motivation, and cognitive impairments. These latter symptoms are related to poorer premorbid functioning and an increased familial risk of schizophrenia. Children with schizophrenia have more-severe premorbid neurodevelopmental abnormalities, increased cytogenetic anomalies, and stronger family histories of psychotic disorders in comparison to their adult counterparts.

Table 28-6 DSM-IV-TR DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR SCHIZOPHRENIA

From American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision, Washington, DC, 2000, American Psychiatric Association.

Etiology

Velocardiofacial syndrome (VCFS or diGeorge Syndrome; Chapter 119) is associated with psychosis in childhood and in adult life. The deletion on chromosome 22q11.2 found in VCFS is 80 times more common in adults with schizophrenia and 240 times more common in childhood-onset schizophrenia. Childhood-onset schizophrenia is preceded by and comorbid with PDD in 30-50% of cases.

Treatment

First-generation (typical) and second-generation (atypical) antipsychotic medications have been shown to be effective in reducing psychotic symptoms (Chapter 19 and Table 19-5). In general, the atypical medications have become the first line of treatment in this disorder. Although clozapine has been shown to be effective in treating both positive and negative symptoms, its increased risk for agranulocytosis and seizures has limited its use until after multiple trials of other antipsychotic medications have failed.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, ed 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with schizophrenia. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(Suppl):4S-23S.

Fazel S, Langstrom N, Hjern A, et al. Schizophrenia, substance abuse, and violent crime. JAMA. 2009;301:2016-2023.

Kahn RS, Fleischhacker WW, Boter H, et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in first-episode schizophrenia and schizophreniform disorder: an open randomized clinical trial. Lancet. 2009;371:1085-1096.

Kumra S, Schulz SC. Editorial: research progress in early-onset schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2008;34:15-17.

Nicodemus KK, Law AJ, Radulesca E, et al. Biological validation of increased schizophrenia risk with NRG1, ERBB4, and AKT1 epistasis via functional neuroimaging in healthy controls. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(10):991-1001.

Rapoport J, Chavez A, Greenstein D, et al. Autism spectrum disorders and childhood-onset schizophrenia: clinical and biological contributions to a relation revisited. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48:10-16.

Ray WA, Chung CP, Murray KT, et al. Atypical antipsychotic drugs and the risk of sudden cardiac death. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:225-234.

Read J, van Os J, Morrison AP, Ross CA. Childhood trauma, psychosis and schizophrenia: a literature review with theoretical and clinical implications. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2005;112:330-350.

Wicks S, Hjern A, Dalman C. Social risk or genetic liability for psychosis? A study of children born in Sweden and reared by adoptive parents. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:1240-1246.

Xu B, Roos JL, Levy S, et al. Strong association of de novo copy number mutations with sporadic schizophrenia. Nat Genet. 2008;40:880-885.

28.5 Psychosis Associated with Epilepsy

The diagnosis requires a strong index of suspicion and EEG monitoring.

Devinsky O. Postictal psychosis: common, dangerous, and treatable. Epilepsy Curr. 2008;8:31-34.

Elliott B, Joyce E, Shorvon S. Delusions, illusions and hallucinations in epilepsy: 2. Complex phenomena and psychosis. Epilepsy Res. 2009;85(2–3):172-186.

Farooq S, Sherin A: Interventions for psychotic symptoms concomitant with epilepsy (review), Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4):CD006118, 2008.

Joshi CN, Booth FA, Sigurdson ES, et al. Postictal psychosis in a child. Pediatr Neurol. 2006;34:388-391.

Kanner AM, Dunn DW. Diagnosis and management of depression and psychosis in children and adolescents with epilepsy. J Child Neurol. 2004;19:S65-S72.

28.6 Acute Phobic Hallucinations of Childhood

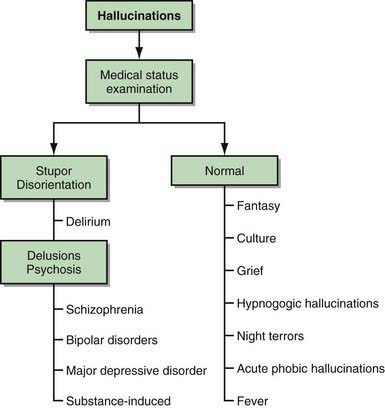

Among adults, hallucinations are viewed as synonymous with psychosis and as harbingers of serious psychopathology. In children, hallucinations can be part of normal development or can be associated with nonpsychotic psychopathology, psychosocial stressors, drug intoxication, or physical illness. The first clinical task in evaluating children and adolescents who report hallucinations is to sort out those that are associated with severe mental illness from those that derive from other causes (Fig. 28-2).

Figure 28-2 Evaluation of hallucinations.

(From Kliegman RM, Greenbaum LA, Lye PS: Practical strategies in pediatric diagnosis and therapy, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2004, Elsevier/Saunders, p 601.)

McGee R, Williams S, Poulton R. Hallucinations in nonpsychotic children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:12-13.

Owen MJ, Craddock N. Diagnosis of functional psychoses: time to face the future. Lancet. 2009;373:190-191.

Schreier A, Wolke D, Thomas K, et al. Prospective study of peer victimization in childhood and psychotic symptoms in a nonclinical population at age 12 years. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:527-536.

Sosland M, Edelsohn G. Hallucinations in children. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2005;7:180-188.