CHAPTER 15 Peripheral vascular disease

Arterial

Examination

The patient’s limb should be examined in a warm room.

Palpation

Check the skin temperature. Check the capillary refilling time, i.e. press the tip of the nail or pulp of the toe or finger for 2 s and observe the time taken for the blanched area to turn pink. In the normal digit this should occur immediately. Delay (>2 s) will occur in the ischaemic digit. Palpate and record all the pulses. They should be assessed for strength (assessed as normal, weak or absent). Pulses should be recorded as shown in Table 15.1 and the presence of any aneurysmal dilatation noted.

| Pulses | R | L |

|---|---|---|

| Radial | ++ | ++ |

| Brachial | ++ | ++ |

| Subclavian | ++ | ++ |

| Carotid | ++ (bruit) | ++ |

| Femoral | ++ | ++ (bruit) |

| Popliteal | + | − |

| Posterior tibial | − | − |

| Dorsalis pedis | − | − |

Arterial occlusive disease

Acute arterial occlusion

Investigations

Treatment

The further management depends on the clinical condition of the limb. Options include:

Chronic arterial occlusion

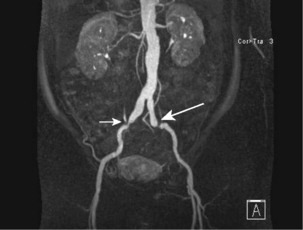

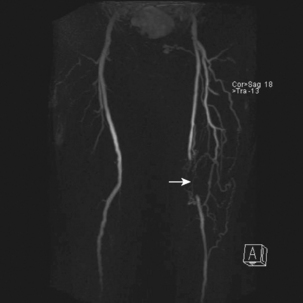

Lower limb (aorto-ilio-femoral disease)

Investigations

Treatment

Medical

Surgical

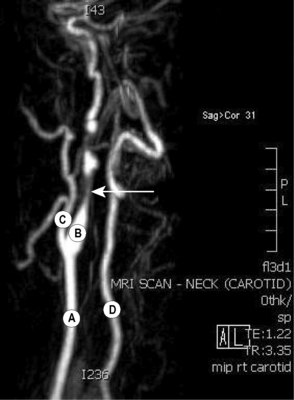

Cerebrovascular disease

Symptoms and signs

These may be classed as carotid (anterior circulation) or vertebrobasilar (posterior circulation).

Investigations

Renovascular disease

Visceral ischaemic disease

Acute mesenteric ischaemia

Aneurysms

An aneurysm is an abnormal dilatation of an artery. Aneurysms may be true or false (see below). A true aneurysm contains all layers of the vessel wall and appears as either a fusiform or a saccular dilatation. True aneurysms are commonest in the infrarenal aorta, iliac vessels, common femoral and popliteal arteries. A false aneurysm may occur anywhere and is usually the result of trauma. (For Classification of aneurysms → Table 15.2.)

| True | |

| Congenital | Berry aneurysm of circle of Willis |

| Aneurysmal varix associated with arteriovenous fistula | |

| Acquired | Trauma: irradiation |

| Infection: syphilis, mycotic aneurysm | |

| Degeneration: arteriosclerosis, cystic medical necrosis | |

| False | Trauma |

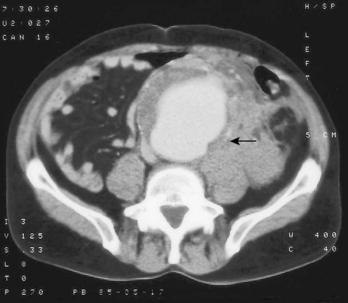

Aortic aneurysms

An aorta may be aneurysmal from the ascending aorta to the aortic bifurcation. Aortic aneurysms can be divided into thoracic (→ Ch. 9), thoracoabdominal or abdominal alone. Abdominal infrarenal aortic aneurysm is the most common type.

Complications

Other vascular problems

Raynaud’s phenomenon

This is a vasospastic condition of diverse aetiology. The following conditions have been implicated:

Diabetic foot

Thoracic outlet syndrome

Investigations

Arteriovenous fistula

Amputations

Principles of amputation

Types of amputation

Venous disorders

Varicose veins

These are dilated tortuous veins. They are divided into primary and secondary.

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT)

Investigations

Chronic venous insufficiency

This is caused by persistent and sustained ambulatory venous hypertension. Causes include:

Investigations

Treatment

Difficult to treat and patient rarely gets complete relief.

Surgery

Options for surgical intervention include:

Superficial thrombophlebitis

This is characterized by a local inflammation of a segment of superficial vein. The vein is tender, red and feels like a ‘cord’. The causes are shown in Table 15.3. Treatment is usually symptomatic and depends on the underlying cause. However, when it involves the great saphenous vein at the saphenofemoral junction, this has a risk of thromboembolism and is treated as for a DVT with anticoagulation or urgent ligation.

| Varicose veins |

| Occult carcinoma: |

Lymphoedema

Secondary

Symptoms and signs

There is progressive swelling of one or both extremities, usually beginning around the ankle but often involving the whole extremity. The scrotum may be involved. Oedema is non-pitting and does not settle with elevation. Often the leg aches and feels tight but there is no pain. Minor trauma will cause cellulitis. Need to differentiate from other causes of leg swelling (→ Table 15.4).

| Local | |

| Acute swelling | Trauma |

| DVT | |

| Cellulitis | |

| Allergy | |

| Rheumatoid | |

| Ruptured Baker’s cyst | |

| Chronic swelling | Venous: |

| •varicose veins (uncomplicated varicose veins rarely cause leg swelling) | |

| •obstruction to venous return, e.g. pregnancy, pelvic tumours, IVC | |

| •obstruction, post-phlebitic limb | |

| Lymphoedema | |

| Congenital malformations, e.g. arteriovenous fistulae | |

| Paralysis (failure of muscle pump) | |

| Dependency | |

| General | Congestive cardiac failure |

| Hypoproteinaemia, e.g. liver failure | |

| Nephrotic syndrome, malnutrition | |

| Renal failure | |

| Fluid overload | |

| Myxoedema |

Investigations

Vascular trauma

Investigations

There may be no time for investigations, as urgent transfer to theatre may be required.

Treatment

Principles of treatment include:

Emergency measures

Principles of surgical management include:

Complications

Femoral embolectomy

The stages of a femoral embolectomy are as follows: