Peripheral neuropathies I

Clinical approach and investigations

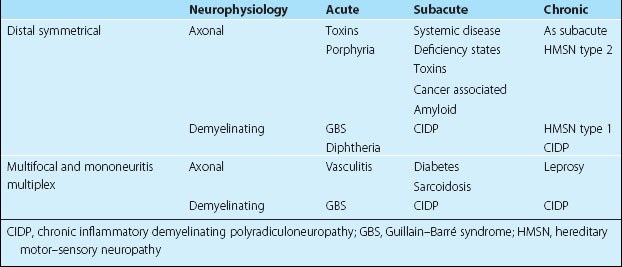

Peripheral neuropathies are very variable, both in their clinical manifestations and in their aetiology (Table 1). These three sections give an overview of peripheral nerve disease, with the third concentrating on the common isolated peripheral nerve lesions.

Pathology

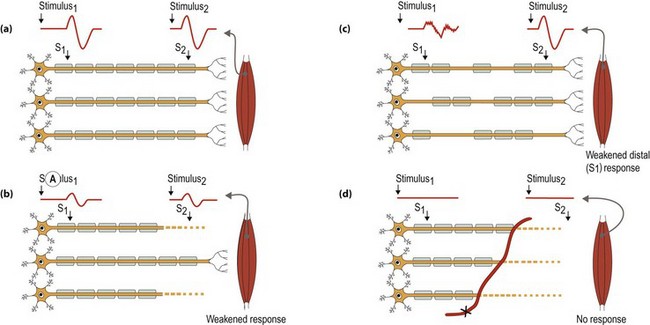

Peripheral nerves can be affected in three ways (Fig. 1). These mechanisms of injury are not mutually exclusive and in some conditions there are contributions from all three mechanisms:

Clinical features

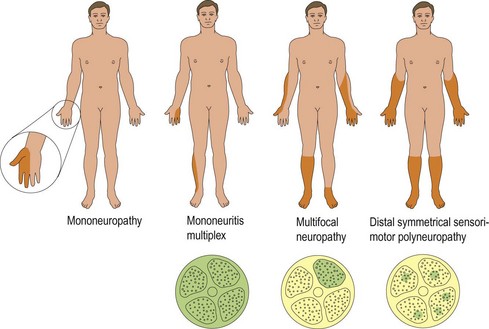

There are four patterns of clinical presentation of peripheral nerve disease (Fig. 2):

Diagnosis and differential diagnosis

The diagnosis of a peripheral neuropathy falls into two parts.

Is it a peripheral neuropathy?

Patients with an acute-onset weakness of the arms and legs. The differential diagnosis here is between an acute neuropathy, usually Guillain–Barré syndrome, a cervical spinal cord or brain stem lesion, myasthenia gravis and an acute myopathy. Reflex changes, sensory findings and ancillary investigations including nerve conduction studies may be needed to clarify this. N.B. The most common and dangerous erroneous differential diagnosis given in patients with acute neuropathies is hysteria.

Patients with an acute-onset weakness of the arms and legs. The differential diagnosis here is between an acute neuropathy, usually Guillain–Barré syndrome, a cervical spinal cord or brain stem lesion, myasthenia gravis and an acute myopathy. Reflex changes, sensory findings and ancillary investigations including nerve conduction studies may be needed to clarify this. N.B. The most common and dangerous erroneous differential diagnosis given in patients with acute neuropathies is hysteria.Investigations

A patient with an axonal distal sensorimotor neuropathy without a clinical indicator of aetiology will need a screen of investigations to look for systemic and deficiency states (Box 1).