97 Peripheral Nerve Disorders

• Nerve compression is the most common cause of radiculopathy and mononeuropathy.

• Radiculopathy and radicular pain are typically associated with symptoms within a dermatome or myotome.

• Patients with mononeuropathy have symptoms limited to a single peripheral nerve.

• Guillain-Barré syndrome is an autoimmune demyelinating disease that results in primarily motor symptoms, with severe disease leading to respiratory compromise.

• Myasthenia gravis and Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome are both autoimmune disorders of the neuromuscular junction; myasthenia gravis affects the postsynaptic membrane, whereas Lambert-Eaton syndrome affects the presynaptic membrane.

• Botulism is a toxin-mediated disorder of the neuromuscular junction.

• Systemic diseases such as diabetes mellitus and human immunodeficiency virus infection can result in several peripheral nerve disorders.

Perspective

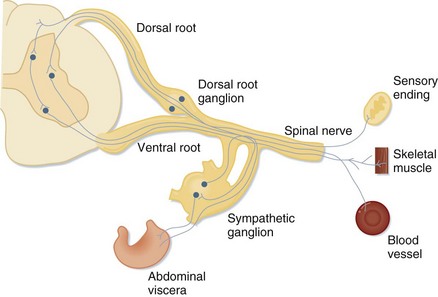

Evaluation of peripheral nerve disorders requires an understanding of the anatomy of the spinal cord and the peripheral nervous system (Fig. 97.1). The peripheral nervous system is composed of 12 cranial nerves and 31 spinal nerves. Spinal nerves are formed from motor fibers whose cell bodies reside in the ventral horn of the spinal cord and from sensory fibers whose cell bodies are found in the dorsal root ganglion. The motor and sensory fibers join to form one nerve as it exits the spinal canal. Spinal nerves from several spinal levels merge at the cervical, brachial, lumbar, and sacral plexuses. Peripheral nerves originate either at these plexuses or, if they are formed from nerves of only one spinal level, as they exit the vertebral foramina.

Systemic diseases affect the peripheral nervous system as well, and multiple peripheral nerves may be involved. Examples include disorders of the neuromuscular junction (NMJ), demyelinating disorders, diabetes, and toxic effects of drugs or chemicals (Box 97.1).

Radiculopathies

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

As noted, sensory loss and weakness follow a dermatomal or myotomal distribution. Diminished reflexes may also assist in determining the nerve root that is involved (Table 97.1).

| NERVE ROOT | REFLEX |

|---|---|

| C5-6 | Brachioradialis |

| C7-8 | Triceps |

| L3-4 | Patellar |

| S1 | Achilles |

Treatment

In the acute phase of injury, painful symptoms are typically treated conservatively with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and physical therapy. Low-quality evidence suggests that there is no difference between bed rest and activity for patients with sciatica.1 However, a randomized controlled trial showed that the addition of physical therapy is more effective than counseling and pain medications alone, although it may not be as cost-effective.2 Persistent or severe symptoms may require more invasive measures, from local corticosteroid injections to neurosurgical intervention.3 For the cervical spinal nerves, some evidence has shown that conservative therapy consisting of pain control has favorable short-term outcomes when compared with surgical intervention, although long-term outcomes appear to be similar.4 Surgical outcomes can be dependent on the mechanism of injury; for example, with spinal stenosis, 70% of patients will still have persistent loss of function. Chronic pain symptoms may be treated with medications used for neuropathic pain, such as antidepressants or anticonvulsants.

Mononeuropathies

Epidemiology

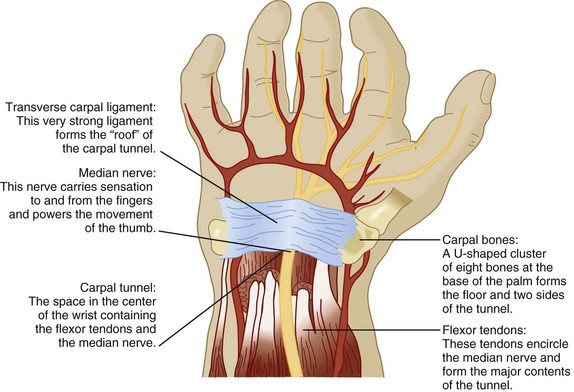

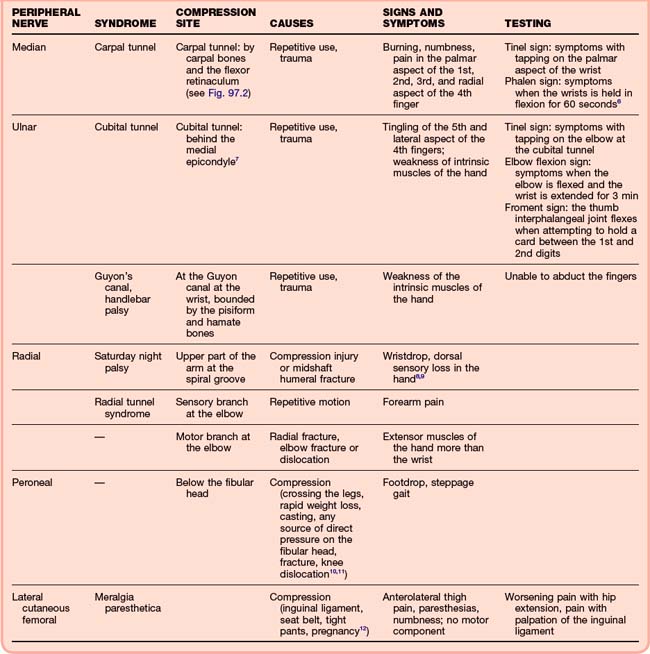

As with radiculopathy, compression of peripheral nerves is the most common cause of peripheral mononeuropathy, the most frequent being median mononeuropathy (Fig. 97.2). Women older than 55 years are most commonly affected, with a 4.6% prevalence in women and 2.8% in men.5 The second most frequent cause is ulnar mononeuropathy; specifically, cubital tunnel syndrome. Other common peripheral mononeuropathies include involvement of the radial nerve in the upper extremity and the peroneal and lateral cutaneous femoral nerves in the lower extremity.

Pathophysiology, Presenting Signs and Symptoms, and Diagnostic Testing

For mononeuropathies, the history and physical examination largely lead to the appropriate diagnosis. Findings in patients with common mononeuropathies and diagnostic maneuvers are presented in Table 97.2.6–12 In patients with a history of trauma or acute symptoms, plain films may be necessary to rule out fracture or dislocation. Patients with subacute or chronic symptoms should be asked about chronic conditions. Mononeuropathies can occur with several systemic diseases, including diabetes mellitus, amyloidosis, HIV, and states that cause edema, such as pregnancy.13 Outpatient testing may be more appropriate for individuals with chronic symptoms. MRI or electrodiagnostic testing such as electromyography or nerve conduction studies may be necessary, and the patient should be referred to a neurologist. MRI may demonstrate chronic nerve injury, whereas electrodiagnostic testing may show slowing of nerve conduction. These studies may aid in deciding whether surgical repair or decompression is necessary for certain syndromes.

Treatment

Initial treatment of chronic mononeuropathy is typically conservative and supportive. Modification of behavior is a key component of treatment and prevention of further injury. For carpal tunnel syndrome, behavior modification includes weight loss and avoidance of caffeine, nicotine, and alcohol. Patients should be instructed to decrease any possible trauma related to repetitive use by making changes in workplace ergonomics, reducing repetitive use, and changing posture. Some neuropathies may require supportive devices; for example, the carpal tunnel may benefit from wearing a wrist splint, the ulnar nerve from wearing a sling or a long arm posterior splint, the radial nerve from wearing a volar splint, and the peroneal nerve from wearing a posterior splint.8,9 NSAIDs are typically prescribed for relief of symptoms, although they may be ineffective without appropriate behavioral modification. In patients with a systemic disease, the primary process should be treated. Diuretics may be given if edema is believed to be contributing significantly to the patient’s symptoms. More invasive procedures, such as local nerve block for meralgia paresthetica or surgical decompression for carpal tunnel syndrome, are reserved for severe cases.

Autoimmune Disorders

Guillain-Barré Syndrome

Epidemiology

Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) is also known as acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculopathy or Landry-Guillain-Barré syndrome. Its worldwide incidence is 0.6 to 4 per 100,000 individuals annually.14

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Classic Guillain-Barré Syndrome

Classic GBS is preceded by a viral prodrome and followed by acute or subacute ascending symmetric weakness or paralysis and loss of the deep tendon reflexes. Paralysis may ascend to the diaphragm and compromise respiratory function to the extent that mechanical ventilation is required. One third of patients will require intubation and 15% will experience dysautonomia. Specific findings are strongly suggestive of this diagnosis (Box 97.2).

Diagnostic Testing

It is critical that respiratory function be assessed early and often because maintenance of airway protection well in advance of respiratory compromise decreases the incidence of aspiration and other complications of emergency intubation (Box 97.3). The most studied monitoring parameter is vital capacity (VC), with normal values ranging from 60 to 70 mL/kg. However, a simple bedside assessment of respiratory status can be obtained by having the patient count from 1 to 25 with a single breath and trending the values over time.

If the patient’s condition does not initially meet the criteria for intubation, VC should be monitored closely—every hour for the first 4 hours and then every 4 hours.15

Treatment

Corticosteroids have shown no benefit in the management of GBS and may be harmful. The two modalities that have clearly proved to be beneficial are intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and plasmapheresis. Both provide an equal, but not additive reduction in the duration of symptoms if given within 2 weeks of onset to ambulatory patients and within 4 weeks to nonambulatory patients. Plasmapheresis has been associated with more treatment complications and adverse events, including hemodynamic instability, which has resulted in a higher rate of discontinuation. However, it is also associated with a lower relapse rate. Overall, fewer complications occur with IVIG, although thromboembolism and aseptic meningitis have been reported.16

Myasthenia Gravis

Pathophysiology

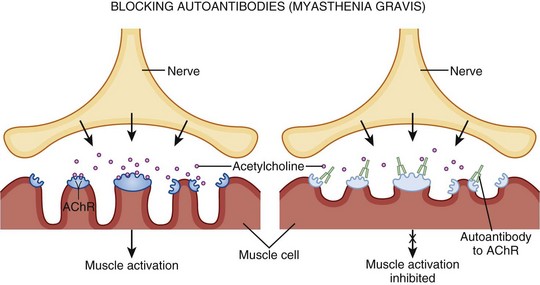

Myasthenia gravis has many causes, but they all lead to the formation of autoantibodies directed against nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (AChRs) at the NMJ (Fig. 97.3). This results in autoimmune destruction of AChRs through complement-mediated destruction, as well as increased endocytosis by muscle cells. The autoantibodies further compete with acetylcholine (ACh) for binding at the remaining receptors. Thus with repeated stimulation of the same muscle, fewer and fewer sites are available and fatigue develops.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Acute Myasthenic Crisis

Underlying infection, aspiration, and changes in medications most often trigger myasthenic crisis, but the precipitant may not be found in up to 30% of cases (Box 97.4).

Diagnostic Testing

The diagnosis is based on clinical findings, bedside testing, and serologic studies.

Bedside Testing

The edrophonium test is a pharmacologic test involving the use of a short-acting acetylcholinesterase (AChE)-blocking agent that can be done at the patient’s bedside.17 The test confirms the diagnosis of myasthenia if the ptosis improves after the intravenous administration of edrophonium. An initial dose of 1 mg is given and the patient is observed for an adverse reaction or improvement in the symptoms of ptosis, medial rectus weakness, or dysphonia. If unimproved in 30 to 90 seconds, a second dose of 3 mg is given. Another 3-mg dose of edrophonium is administered if no response is seen after 30 to 60 seconds. If there is still no response, a final dose of 3 mg is given, for a total maximum dosage of 10 mg. Edrophonium may result in a severe anticholinergic reaction, especially in the elderly, cardiac disease patients, those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or asthmatics. Symptoms include salivation and gastrointestinal cramping but may be more severe, such as bradycardia, bronchorrhea, bronchospasm, and worsening weakness. Because of the potential for bradycardia, atropine should be at the bedside during edrophonium testing.

The ice test is another bedside test that can be used to quickly confirm the diagnosis. Cooling decreases the symptoms of myasthenia gravis, whereas heat exacerbates them. In this test the distance between the upper and lower lids is measured before the application of an ice pack for 2 to 3 minutes to the most severely affected eye.18

Treatment

Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors

AChE inhibitors such as pyridostigmine and neostigmine are the backbone of outpatient chronic therapy and provide symptomatic improvement.2 This class of drugs inhibits the hydrolysis of ACh, which leads to an increased circulating concentration of ACh to compete with the antibody for AChR binding sites. The most common side effects are those of excessive cholinergic stimulation as mentioned earlier. These drugs are not directed at the underlying immunologic basis of the disease and are often used as adjunctive therapy to control symptoms while allowing time for other therapy to take effect, after which they are discontinued.19

The use of intravenous pyridostigmine in the setting of acute exacerbation of myasthenia gravis is controversial. Some evidence indicates that its use may complicate ventilation by worsening pulmonary secretions.20 Consequently, cholinergic drug therapy should be discontinued during a myasthenic crisis. In addition, a cholinergic crisis characterized by acute decompensation and excessive muscarinic stimulation may be caused by excessive medication with AChE inhibitors. Cholinergic crisis should be distinguished from an exacerbation of the disease by muscarinic findings on physical examination: excessive sweating, salivation, lacrimation, miosis, tachycardia, and gastrointestinal hyperactivity.

Lambert-Eaton Myasthenic Syndrome

Epidemiology

Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS) is relatively uncommon, with a prevalence of 1 in 100,000 individuals. The disease occurs predominantly in those older than 50 years, with both genders affected equally.22

Pathophysiology

Frequently, this disease is associated with other pathology. Malignancies are often seen with LEMS, with upward of 70% of cases having a concomitant malignancy. The most common association is with small cell lung cancer: 62% of cases have this link.19 Diagnosis of the malignancy may come after the diagnosis of LEMS. Because LEMS is an autoimmune disorder, it is also associated with other autoimmune disorders, including hypothyroidism, pernicious anemia, and celiac disease.23

Treatment

The most effective treatment of LEMS involves treatment of the primary malignancy if present. Other treatments have been used over the years, including immunosuppressants such as prednisone, pyridostigmine (AChE inhibitor), plasma exchange, IVIG, and 3,4-diaminopyridine (3,4-DAP). 3,4-DAP is an oral medication that blocks potassium channels and prevents repolarization and removal of calcium from the cell. Evidence for the efficacy of these therapies is limited because the disease itself is uncommon, although randomized controlled trials have found improvement with IVIG and 3,4-DAP.24

Systemic Disorders

Botulism

Epidemiology

Botulism is a toxin-mediated illness that can cause acute weakness leading to respiratory failure. In 2009, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported 121 cases of botulism: 69% were categorized as infantile, 19% as wound, and 9% as food-borne botulism. In 2009, of the 23 cases of wound botulism, 21 resulted from injection drug use.25

Pathophysiology

Clostridium botulinum, the causative organism, is an anaerobic spore-forming bacterium. Three of eight known toxins produced by C. botulinum cause human disease: toxin types A, B, and E. Most cases of botulism are isolated events associated with improperly preserved canned foods, although the incidence of botulism from wound infections has recently increased. Toxin type E is associated with preserved or fermented fish and marine mammals. These are the most important sources of botulism in Alaska, Japan, Russia, and Scandinavia.26

Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy

Epidemiology

A common complication of diabetes, diabetic peripheral neuropathy has a varied prevalence ranging from 34% to 60%, although higher rates often include asymptomatic neuropathies. It is a highly variable entity that is composed of several subsets. Of the various subsets of diabetic neuropathy, distal symmetric polyneuropathy is the most common, with up to 54% of patients with diabetic neuropathy having this variant. It is seen in patients with type 1 diabetes after 5 years and early in the course of type 2 diabetes.27,28

Pathophysiology

Hyperglycemia affects the peripheral nerves by several proposed mechanisms:

2. Glycosylation of nerve proteins

3. Changes in the diabetic vasculature resulting in increased resistance and decreased flow to the peripheral nerves

Motor, sensory, and small and large fibers can all be involved. Diabetic peripheral neuropathy is an example of a distal axonopathy resulting in length-dependent “dying back” of the affected nerves. This dying-back phenomenon produces the typical stocking-and-glove distribution of diabetic neuropathy.29

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

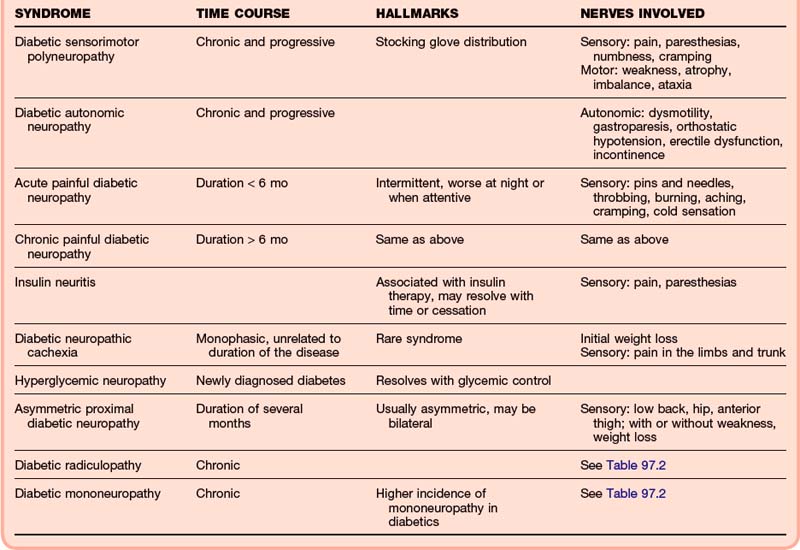

Several neuropathic syndromes can be found in diabetic patients and are often present concurrently (Table 97.3). For example, patients may have a sensorimotor polyneuropathy with subsequent development of a mononeuropathy of the upper extremity.30

Treatment

Disease modification has the greatest effect on the progression of diabetic neuropathy; although the cause is multifactorial, a clear relationship between glycemic control and neuropathy exists. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial showed a 60% reduction in risk for the development of neuropathy with tight glycemic control.31

Management of symptoms is the patient’s most immediate concern. NSAIDs may alleviate discomfort but are relatively contraindicated in diabetic patients. Narcotics carry addictive potential. Off-label use of tricyclics, antidepressants, anticonvulsants, and topical capsaicin have all proved beneficial (Table 97.4).32,33

Table 97.4 Initial Therapy for Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy (Based on a 70-kg Adult)

| Tricyclic antidepressants | Amitriptyline, 25-100 mg PO daily Nortriptyline, 10-25 mg PO daily |

| Anticonvulsants | Gabapentin, 900 mg PO daily or divided TID |

| Valproate, 500-1200 mg PO daily or divided BID | |

| Topical | Capsaicin 0.075%, up to 4 times daily Lidocaine 5% patch, 1 patch daily |

Human Immunodeficiency Virus–Associated Peripheral Neuropathy

Epidemiology

Peripheral nervous system disease associated with HIV infection most commonly takes the form of a distal sensory polyneuropathy. The prevalence of symptomatic patients is 35%, although an additional 20% of asymptomatic patients have electrophysiologic evidence of disease.34

Pathophysiology

The distal peripheral neuropathy associated with HIV disease has two causes. There does not appear to be direct nervous invasion by HIV, although proteins produced by the virus may have associated neurotoxicity. The resultant inflammatory mediators, including macrophages and cytokines, probably play a role as well. Since the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), a second proposed mechanism has implicated mitochondrial toxicity because of the medications themselves. Both causes primarily affect small unmyelinated fibers and may progress to involve larger myelinated fibers. The neuropathy demonstrates a dying-back axonal pattern with distal axonal degeneration.35

Treatment

The goals of treatment are similar to those for diabetic peripheral neuropathy: control of the primary disease process is important. Potential toxic drugs should be discontinued if appropriate. Painful neuropathy may be managed with NSAIDs, topical analgesics such as lidocaine patches, anticonvulsants, antidepressants, or narcotic analgesics.36 Randomized controlled trials have demonstrated the effectiveness of pain control over placebo along with the use of specific antiepileptics such as gabapentin and lamotrigine.35,37

Follow-up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

Most patients with peripheral nerve disease can be treated on an outpatient basis. For patients with radiculopathy, compression mononeuropathy, or plexopathy, conservative treatment with analgesics and physical therapy is appropriate initially. This conservative treatment may take several weeks to reach maximal effect, which is important to convey to patients to improve compliance. Diabetics in particular may also benefit from referral to podiatry to prevent the complications of diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Patients with persistent symptoms despite a trial of conservative care may require referral for diagnostic testing with MRI or electrodiagnostics, pain management, or surgical evaluation.38 Patients with acute injury, such as fracture or dislocation, will require either immediate consultation by or follow-up with an orthopedist or hand specialist.

Dahm KT, Brurberg KG, Jamtvedt G, et al. Advice to rest in bed versus advice to stay active for acute low back pain and sciatica. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 6, 2010. CD007612

Lawn ND, Fletcher DD, Henderson RD, et al. Anticipating mechanical ventilation in Guillain-Barré syndrome. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:893–898.

Pascuzzi RM. The edrophonium test. Semin Neurol. 2003;23:83–88.

1993 The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:977–986.

1 Dahm KT, Brurberg KG, Jamtvedt G, et al. Advice to rest in bed versus advice to stay active for acute low back pain and sciatica. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 6, 2010. CD007612

2 Luijsterburg PA, Verhagen AP, Ostelo RW, et al. Physical therapy plus general practitioners’ care versus general practitioners’ care alone for sciatica: a randomised clinical trial with a 12-month follow-up. Eur Spine J. 2008;17:509–517.

3 Van Boxem K, Chang J, Patijn J, et al. Lumbosacral radicular pain. Pain Pract. 2010;10:339–358.

4 Nikolaidis I, Fouyas IP, Sandercock PA, et al. Surgery for cervical radiculopathy or myelopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1, 2010. CD001466

5 Atroshi I, Gummesson C, Johnsson R, et al. Prevalence of carpal tunnel syndrome in a general population. JAMA. 1999;282:153–158.

6 Jillapalli D, Shefner JM. Electrodiagnosis in common mononeuropathies and plexopathies. Semin Neurol. 2005;25:196–203.

7 Robertson C, Saratsiotis J. A review of compressive ulnar neuropathy at the elbow. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2005;28:345.

8 Dawson DM. Entrapment neuropathies of the upper extremities. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:2013–2018.

9 Van den Ende K, Steinman SP. Radial tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 2010;35:1004–1006.

10 Stewart JD. Foot drop: where, why, and what to do? Pract Neurol. 2008;8:158–169.

11 Katirji B. Peroneal neuropathy. Neurol Clin. 1999;17:567–591.

12 Grossman MG, Ducey SA, Nadler SS, et al. Meralgia paresthetica: diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2001;9:336–344.

13 Katz JN, Simmons BP. Clinical practice: carpal tunnel syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1807–1812.

14 Vucic S, Kiernan MC, Cornblath DR. Guillain-Barré syndrome: an update. J Clin Neurosci. 2009;19:733–741.

15 Lawn ND, Fletcher DD, Henderson RD, et al. Anticipating mechanical ventilation in Guillain-Barré syndrome. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:893–898.

16 Sederholm BH. Treatment of acute immune-mediated neuropathies: Guillain-Barré syndrome and clinical variants. Semin Neurol. 2010;30:365–372.

17 Pascuzzi RM. The edrophonium test. Semin Neurol. 2003;23:83–88.

18 Massey JM. Acquired myasthenia gravis. Neurol Clin. 1997;15:577–596.

19 Jani-Acsadi A, Lisak RP. Myasthenic crisis: guidelines for prevention and treatment. J Neurol Sci. 2007;261:127–133.

20 Dalakas MC. Intravenous immunoglobulin in autoimmune neuromuscular diseases. JAMA. 2004;291:2367–2375.

21 Petty R. Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome. Pract Neurol. 2007;7:265–267.

22 O’Neill JH, Murray NMF, Newsom-Davis J. The Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome: a review of 50 cases. Brain. 1988;111:577–596.

23 Mareska M, Gutmann L. Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome. Semin Neurol. 2004;24:149–153.

24 Maddison P, Newsom-David J. Treatment for Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2, 2005. CD003279

25 CDC Division of Bacterial and Mycotic Diseases. Summary of botulism cases reported in. http://www.cdc.gov/nationalsurveillance/PDFs/Botulism_CSTE_2009.pdf, 2009. Available at

26 CDC Division of Bacterial and Mycotic Diseases. Surveillance for botulism. Summary of 2005 data. Available at www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dbmd/diseaseinfo/files/BOTCSTE2005.pdf

27 Dyck PJ, Kratz KM, Karnes JL, et al. The prevalence by staged severity of various types of diabetic neuropathy, retinopathy, and nephropathy in a population based cohort: the Rochester Diabetic Neuropathy Study. Neurology. 1993;43:817–824.

28 Maser RE, Steenkiste AR, Dorman JS, et al. Epidemiologic correlates of diabetic neuropathy. Report from Pittsburgh Epidemiology of Diabetic Complications Study. Diabetes. 1989;38:1456–1461.

29 Kelkar P. Diabetic neuropathy. Semin Neurol. 2005;25:168–173.

30 Tracy JA, Dyck PJ. The spectrum of diabetic neuropathies. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2008;19:1–26.

31 The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:977–986.

32 Sindrup SH, Otto M, Finnerup NB, et al. Antidepressants in the treatment of neuropathic pain. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005;96:399–409.

33 Argoff CE, Backonja MM, Belgrade MJ, et al. Consensus guidelines: treatment planning and options. Diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(4 Suppl):S12–S25.

34 Schifitto G, McDermott MP, McArthur JC, et al. Incidence of and risk factors for HIV-associated distal sensory polyneuropathy. Neurology. 2002;58:1764–1768.

35 Hahn K, Arendt G, Braun JS, et al. A placebo controlled trial of gabapentin for painful HIV-associated sensory neuropathies. J Neurol. 2004;251:1260–1266.

36 Gonzalez-Duarte A, Cikurel K, Simpson DM. Managing HIV peripheral neuropathy. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2007;4:114–118.

37 Simpson DM, McArthur JC, Olney R, et al. Lamotrigine for HIV-associated painful sensory neuropathies: a placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 2003;60:1508–1514.

38 Campbell WW. Diagnosis and management of common compression and entrapment neuropathies. Neurol Clin. 1997;15:549–567.