CHAPTER 8 Peripheral nerve blockade for ambulatory surgery

Introduction

Over the last 15–20 years there has been a rapid increase worldwide in the numbers of surgical patients being treated in the ambulatory setting. While the main driving force has been a financial one, there are many benefits for patients including faster return home, greater access to treatment, and innovations in both anesthetic and surgical techniques to facilitate the rapid discharge of patients from hospital.1

Anesthesia provided in the ambulatory setting must be such that the patient is rapidly awake, has minimal postoperative cognitive dysfunction, mild or no pain, a very low risk (<15%) of postoperative nausea and/or vomiting (PONV), is able to commence oral diet within a few hours and is able to ambulate with minimal support (apart from an aid such as a crutch). The ability to void urine is not a requirement unless neuraxial anesthesia has been performed or the patient has undergone a surgical procedure likely to lead to urinary retention. These parameters are necessary in order to avoid unplanned hospital admissions (Box 8.1).

Setting up and running a peripheral nerve blockade service in an ambulatory setting

The starting up and running of a successful PNB service in an ambulatory setting requires consideration of a number of areas,2 which are described in the following paragraphs (Box 8.2).

Working environment

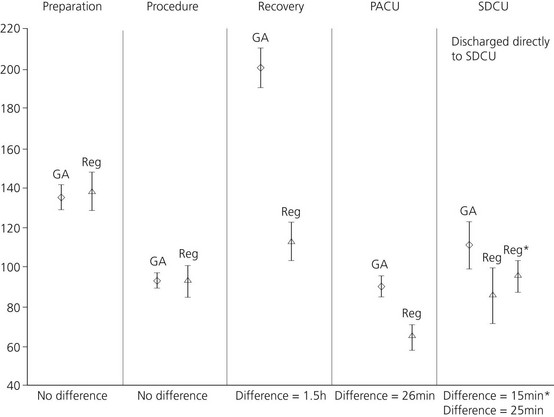

Compared with GA, the performance of PNB takes longer to achieve anesthesia, as the time to onset includes both the time to perform the block and for the LA to act. However, a number of studies3,4 have shown that less time is spent in the operating theatre (20 mins), the PACU (40 mins) and the hospital (40–100 mins), resulting in an overall time gain with PNB compared to GA (Fig. 8.1). There is a 20 minute increase in the amount of time the anesthesiologist spends with the patient.

The use of a dedicated block room has been advocated but this may not be cost effective unless it serves a number of operating theatres and has a regular patient load.4 A more practical solution is to perform the blocks in the PACU, hence utilizing the nursing staff and facilities already available.5

Performance of techniques

Proper preparation is vital for the safe provision of regional anesthesia and this is discussed in greater detail in another chapter of this book. Briefly, the following equipment and drugs are required (Box 8.3) and we would recommend that a dedicated regional anesthesia trolley be organized. Importantly, Intralipid must be stored as part of the emergency drugs.

Although the successful use of Intralipid for LA toxicity in humans has only been documented in case reports, the results have been so dramatic that its use is recommended. Intralipid has been effective in LA toxicity resulting from the long-acting amides bupivacaine, ropivacaine and levobupivacaine. While successful use has been described for the short-acting LA, mepivacaine, to date the only use for lidocaine has been in a pediatric patient who received both lidocaine and ropivacaine for psoas compartment block.6

Modern peripheral nerve blockade is performed using either a nerve-stimulation technique (NST) or ultrasound guidance (USG) to locate the relevant nerves. USG for PNB is generally accepted to result in a faster onset (about 5 minutes), higher success rates (3–10% greater when compared to multi-stimulation techniques) and possibly lower LA volumes compared to NST.7,8 However, whether these differences will result in benefit in the average ambulatory setting is debatable. The advantage of USG may be offset by its significantly increased capital cost.

Choice of local anesthetic

Long-acting LAs such as levobupivacaine and ropivacaine are generally not used because of the prolonged motor blockade. The use of a continuous technique allows lower doses to be used, providing a motor sparing effect, and is useful for more major ambulatory surgery such as shoulder arthroplasty.9 There are no studies in the ambulatory setting comparing the duration of analgesia of long- versus short-acting LAs, but it is reasonable to assume that the benefits seen with long-acting LAs for in patients would be similar. Performing selective analgesic blocks with a long-acting LA while using a short-acting LA for the main block and anesthesia, is an effective technique (for example, for a Dupuytren’s contracture, performing an axillary block with mepivacaine and an ulnar block at the elbow with levobupivacaine).

Postoperative care

Firstly, the anesthesiologist has to be prepared to accept the clinical situation. Even with short-acting LAs, 50% of patients will have residual block present when they are otherwise fit for discharge home.10 The discharge criteria normally used for patients undergoing GA, such as the modified Aldrete score, are inappropriate because they require the patient to move all four limbs.11 A scoring system not requiring limb movement, such as the Postanesthesia discharge scoring system (PADSS), may have to be incorporated into your practice12 (Table 8.1).

Table 8.1 Post-anesthesia discharge scoring system (PADSS) for determining home readiness

| Discharge criteria | Score |

|---|---|

| Vital signs: | |

| Vital signs must be stable and consistent with age and pre-operative baseline | |

| Blood pressure and pulse within 20% of pre-operative baseline | 2 |

| Blood pressure and pulse 20–40% of pre-operative baseline | 1 |

| Blood pressure and pulse >40% of pre-operative baseline | 0 |

| Activity level: | |

| Patient must be able to ambulate at pre-operative level | |

| Steady gait, no dizziness, or meets pre-operative level | 2 |

| Requires assistance | 1 |

| Unable to ambulate | 0 |

| Nausea and vomiting: | |

| Patient should have minimal nausea and vomiting before discharge | |

| Minimal: successfully treated | 2 |

| Moderate: successfully treated with intravenous medication | 1 |

| Severe: continues after repeated treatment | 0 |

| Pain: | |

| Patient should have minimal or no pain before discharge | |

| The level of pain that the patient has should be acceptable to the patient | |

| Pain should be controllable by oral analgesics | |

| The location, type and intensity of pain should be consistent with anticipated postoperative discomfort | |

| Pain acceptable | 2 |

| Pain controllable with oral analgesics | 1 |

| Pain not acceptable | 0 |

| Surgical bleeding: | |

| Postoperative bleeding should be consistent with expected blood loss for the procedure | |

| Minimal: does not require dressing change | 2 |

| Moderate: up to two dressing changes required | 1 |

| Severe: more than three dressing changes required | 0 |

| TOTAL |

Maximum score = 10.

Patients scoring ≥ 9 are fit for discharge.

Modified after Chung F, Chan VW, Ong D. J Clin Anesth 1995;7(6):500–6.

Secondly, discharging a patient home with a long-acting LA block is safe. A study of 1791 patients who underwent a total of 2382 blocks of both the upper and lower limb, with ropivacaine 0.5% in a day surgery setting, found an incidence of paresthesia of 0.25% at 7 days. All had resolved by 3 months. One patient fell getting out of a car following combined femoral and sciatic nerve blocks, with no sequelae.13 Another study found no difference in the incidence of paresthesia at 1 year when comparing axillary block with GA for hand surgery.14

Finally, the patient must be given both verbal and written instructions in the care of the insensate limb. An example information sheet is included (Box 8.4). It should be explained that the limb is numb and must be cared for and protected from injury and temperature extremes until the limb returns to the patient’s own normal sensation and motor function. The use of a sling (upper limb) or crutch (lower limb) is a useful visual reminder. Patients should also be given details of how long the block is expected to last, as well as a contact telephone number should the block persist outside defined parameters, which will depend on the type of LA and/or continuous technique used.

Box 8.4

Patient information sheet post upper limb block

Follow-up is required after discharge and must continue until there is complete resolution of the block. In practice, this usually consists of a telephone contact after 24 hours and on a daily basis thereafter if necessary, although some centers have nurses who visit patients with continuous infusions. Occasionally, the patient will have to re-attend with the anesthesiologist if there is persistence of the block or evidence of neural injury. Any suspicion of neural injury should be rapidly followed-up and confirmed. The guidelines from the Consensus Statement of the American Society of Regional Anesthesia on Neurologic Complications of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, 2005 are useful in this circumstance.15

Patient acceptance and satisfaction

Studies have demonstrated that patients’ acceptance of PNB in the ambulatory setting is very high, with 98% of patients reporting that they would have the same anesthesia technique again.16,13 Patients’ overall satisfaction of a PNB as the principal method of anesthesia is also very high. Using a Likert scale of 1–5, Klein and colleagues found that in a study of over 1700 patients, the mean (± SD) for satisfaction with the PNB technique was 4.88 ± 0.44 at 24 hours and 4.77 ± 0.69 on day 7 post surgery.13

Which upper limb blocks to use for which surgical procedure

Shoulder surgery

The most appropriate block for shoulder surgery is an interscalene block (ISB) because of the consistent blockade of the suprascapular, dorsal scapular and axillary nerves compared with more distal blocks.17

Hadzic et al. demonstrated that for outpatient rotator cuff surgery, single shot ISB resulted in patients having less pain, earlier ambulation and discharge, with no unplanned hospital admissions, compared with patients who received general anesthesia.18

For more extensive surgery such as TSA, severe pain is common and pain control following TSA is important to allow early rehabilitation and discharge from hospital. The use of continuous ISB allows TSA to be performed as a 23-hour ambulatory procedure, with patients discharged home with portable LA pumps and catheters that are either removed by a community nurse or by the patient or their carer.19

Patients undergoing TSA who were randomized to a continuous ISB infusion with ropivacaine 0.2% were suitable for discharge a median of 30 hours (21 vs 51 hours) earlier than patients who received the saline control. They required less intravenous morphine, had less pain and had greater external shoulder rotation.20

Patients undergoing TSA will still require GA and converting this type of surgery into a successful ambulatory procedure requires a well-organized system in place to follow up patients and their continuous catheters at home.21

The effects of ISB on pulmonary function are well known; however, there were no differences found in pulmonary function between a group of patients receiving a continuous ISB infusion and a patient-controlled morphine group.22 Using USG, it is possible to perform an ISB with 5 mL of LA, which reduces the incidence of diaphragmatic paralysis from 100% with 20 mL of LA to 45% with the lower volume.23

The clinical significance of these changes in pulmonary function in patients without pulmonary disease is debatable and respiratory problems have not been reported in patients discharged home following ambulatory overnight TSA.22 This clinical pathway may not be appropriate for patients suffering from pre-existing pulmonary compromise.

Elbow, forearm and hand surgery

Supraclavicular, infraclavicular and axillary brachial plexus blocks are all suitable blocks for elbow, forearm and hand surgery. Mid-humeral and specific nerve blocks at the elbow, wrist and fingers may also have a role, especially in providing selective anesthesia to a particular nerve(s).24

In the ambulatory setting, axillary brachial plexus blockade is often regarded as the most appropriate block because of its high success rate (>95% with USG or multi-stimulation NST) and very low complication rate.7 Concerns regarding the risk of pneumothorax as a complication of the infraclavicular and, in particular, the supraclavicular blocks have been raised, with some anesthesiologists uncomfortable in performing these blocks in an ambulatory setting. These concerns are largely unfounded, especially if USG is applied, which may improve safety by permitting visualization of the needle relative to the pleura and lung. It should be noted that the supraclavicular block, even with the use of USG, is only 85% effective for forearm or hand surgical anesthesia, compared with 95–98% with infraclavicular or axillary blocks.8

A number of randomized studies have compared PNB with GA for ambulatory hand surgery. McCartney et al. compared transarterial axillary block to GA in 100 patients undergoing ambulatory hand surgery.10 Patients who received axillary block reported a longer duration to first analgesic, had lower pain scores and opioid consumption, less nausea/vomiting and spent less time in the hospital than patients receiving general anesthesia. There was no difference in pain scores or opioid consumption on postoperative days 1, 7, and 14, however, and the axillary block had a 10% failure rate, necessitating GA in these patients. USG or multi-stimulation techniques have a failure rate of 3–5% and are recommended instead of the trans-arterial approach.

Hadzic et al. randomized 52 patients undergoing hand and wrist surgery in the ambulatory setting to receive either infraclavicular block with chloroprocaine plus epinephrine and bicarbonate or GA with propofol induction, desflurane maintenance and wound infiltration with bupivacaine. Infraclavicular block led to faster recovery times, lower pain scores (3% vs 48% with pain scores >3), four times less nausea/vomiting and earlier discharge from hospital.25

For surgery on the fingers, a number of techniques for digital anesthesia have been described, including the digital or ‘ring’ block, the intrathecal digital block (injection of local anesthetic into the flexor sheath) and the metacarpal block (local anesthetic injected between and at the level of the metacarpal bones).26 Digital blocks are useful if a tourniquet is not required or as selective long-acting analgesia. These are simple to perform and provide a mean duration of anesthesia of 24.9 hours with bupivacaine 0.5%, 10.4 hours for lidocaine 2% with epinephrine (1 : 100 000) and 4.9 hours for plain lidocaine 2%.26 Epinephrine results in a temporary reduction in digital blood flow but with preservation of digital perfusion.27 An advantage of the intrathecal block is that it involves only a single injection, has a faster onset time (3.91 vs 7.16 min) and better proximal and radial digital anesthesia than metacarpal block.28 Similar findings have been reported for digital block compared to the metacarpal block.

Summary

Upper limb ambulatory surgery performed under PNB results in patients who have less pain, need fewer opioids, have less PONV, resume oral diet and ambulate earlier, and are discharged home sooner that patients undergoing GA. Patients also report greater satisfaction with PNB compared to GA (81 vs 50%).25

Which lower limb blocks to use for which surgical procedure

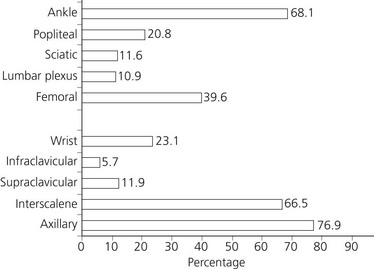

Regional anesthesia in outpatients is common but restricted to a few techniques. In Klein et al.’s survey among 1078 anesthesiologists affiliated to the SAMBA, respondents indicated that they were most likely to perform axillary (77%), interscalene (67%), and ankle blocks (68%) on ambulatory patients but less likely to perform the other lower extremity conduction blocks29 (Fig. 8.2). Discharge with an insensate upper extremity is widely accepted but discharge with an insensate lower extremity or with motor blockade is not common, and seems controversial. Injury from falls may occur without protective reflexes, mainly if a combined block has been used.13 However, the low incidence of such complications is probably related to appropriate patient selection and detailed discharge instructions.

Hip surgery

Hip surgery is one of the most common and classical orthopedic surgical procedures but at present, total hip arthroplasty (THA) is not considered an ambulatory procedure. THA results in relatively severe postoperative pain requiring hospitalization to provide potent analgesia (PCA IV morphine or regional blocks). The average duration of hospitalization after THA is classically 4 to 5 days. Femoral or lumbar plexus block (with sciatic block when indicated) can provide not only excellent anesthesia but also superb analgesia, facilitating timely discharge after THA. Using long acting local anesthetics or placing catheters in the vicinity of the nerves or plexus can achieve longer duration of analgesia. Ilfeld and colleagues reported the feasibility in five patients of converting THA into an overnight-stay procedure using a continuous psoas compartment nerve block provided at home with a portable infusion pump with a continuous infusion of ropivacaine 0.2%.30 All but one patient met the discharge criteria on postoperative day (POD) 1 and three patients were discharged directly home on POD 1. Postoperative pain was well-controlled, opioid requirements and sleep disturbances were minimal, and patient satisfaction was high. Furthermore, the same group evaluated if a 4-day ambulatory continuous lumbar plexus block (LPB) could maximize ambulation distance and decrease the time required to reach three specific readiness-for-discharge criteria after hip arthroplasty, compared with an overnight continuous LPB only. They reported a 38% decrease in the time to reach the three predefined discharge criteria but not an increase in ambulation distance. This technique combined with multi-modal anesthetic and analgesic regimens with associated minimally invasive surgical approaches and rapid rehabilitation protocols, has been incorporated into the management of total joint arthroplasty surgical programs.31,32 In a study of 665 patients utilizing this clinical pathway, Mears and colleagues reported that 38.9% of patients were discharged home with indwelling peripheral nerve catheters. Hospital discharge in less than 24 hours was achieved in 44.4%. After discharge, 73.5% of patients required no home or outpatient nursing care.33

Knee surgery

Knee arthroscopy is well suited as an ambulatory procedure. Analgesia can be provided by intra-articular regional anesthesia and analgesia, as well as from peripheral nerve blockade. Authors evaluated the use of psoas compartment or femoral blocks for knee arthroscopy. Hadzic et al. compared patients scheduled for knee arthroscopies receiving combined psoas compartment block and sciatic nerve block or a GA.34 They reported an incidence of moderate to severe PONV in 12% of patients with combined psoas compartment and sciatic blocks versus 62% with fast-track GA that included prophylactic dolasetron. Peri-operative nerve blocks reduced sore throat, increased ability to bypass phase 1 PACU, and reduced time to meet discharge criteria. Jankowski et al. found that supplemental analgesics were required in 45% of patients receiving a GA compared with only 21% receiving psoas compartment block.35 In addition, the GA group had higher pain scores at 30, 60, 90, and 120 min. However, there is a risk of epidural spread attributed to the paravertebral needle insertion site and high injection pressure that can potentially impede discharge. Femoral nerve block is also used for knee arthroscopy. Better anesthesia resulted from the addition of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve block or an obturator nerve block when compared with the femoral nerve block alone, and this provided improved intra-operative conditions.36 An intra-articular injection of LA alone, a femoral nerve block alone, or a combined intra-articular and femoral nerve block provided acceptable intra-operative anesthesia, excellent surgical conditions, and similar postoperative analgesia in the study by Goranson et al.37 A combination of femoral-sciatic blocks can provide more stable intra-operative hemodynamics with less hypotension, compared with GA.38 In addition, this PNB combination permitted a PACU bypass compared with GA, as well as a shorter length of PACU stay. Furthermore, the femoral-sciatic block had less total anesthesia cost compared with GA. The analgesic potential of femoral nerve blocks can be demonstrated in more painful surgical procedures, such as anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction. Mulroy et al. in a prospective study examined 55 patients having ACL repair under epidural block.39 Postoperatively they received a femoral nerve block with 0.5% bupivacaine or saline. There was superior postoperative analgesia in the block group, whereas 50% of the patients in the sham group reported visual analog scale (VAS) pain scores of greater than 5 out of 10. Iskandar et al. compared a femoral nerve with intra-articular regional analgesia for patients having ACL repair with a hamstring graft.40 They reported better postoperative pain relief in the femoral nerve block group. Nevertheless, when a hamstring graft is used for ACL repair, a significant component of postoperative pain can arise from the sciatic nerve distribution. Williams et al. strongly supported the addition of a sciatic nerve block to a femoral nerve block for more extensive knee surgery.41 In 1200 consecutive outpatients having knee surgery, they reported that single shot/continuous femoral nerve blocks alone provided little benefit for simple arthroscopy but improved analgesia and reduced unanticipated hospital admissions in ligament repairs or more complex arthroscopic knee surgery. In these patients, the addition of a single-shot sciatic nerve block conferred even better postoperative analgesia and fewer hospital admissions. For total knee arthroplasty the use of a continuous 4-day ambulatory femoral block demonstrates improved analgesic, maximizes ambulation distance and decreases the time required to reach three specific readiness-for-discharge criteria, compared to an overnight infusion only.42

Foot and ankle surgery

Popliteal block provides analgesia advantages over both ankle blocks and wound infiltration after foot surgery.43 Randomized studies demonstrated that duration of postoperative analgesia after popliteal block was 1080 mins, compared with 690 mins after ankle block and 709 min after subcutaneous wound infiltration.44 The popliteal block also provided better analgesia and higher patient satisfaction. In painful foot or ankle surgery, White et al. compared prospectively a postoperative continuous popliteal block with 0.25% bupivacaine versus saline.45 The bupivacaine group had lower VAS pain scores for 48 h, 70% less morphine consumption and a shorter length of hospital stay. Similarly, Ilfeld et al. randomized patients to receive a continuous popliteal block with 0.2% ropivacaine or saline, after an induction block with mepivacaine 2%.46 They reported a decrease in postoperative pain, opioid requirements, opioid-related side-effects, and better sleep with fewer awakenings.

Summary

Benefits such as long-lasting analgesia, rapid rehabilitation, better sleep, fewer opioid-related side-effects, and preserved hamstring function support the applicability of PNB for painful hip, knee, and foot and ankle surgery. More frequent use of single-shot injections and, especially, continuous nerve blocks in the ambulatory setting seems warranted (Box 8.5).

Catheters and continuous local anesthesia infusions

The advantages of single-injection PNB are limited because of the relative short duration of long-acting local anesthetics (usually 10–24 h). After resolution of PNB, postoperative pain management is often difficult. The method of continuous PNB infusions is variable, based on institutional practice and the cost and availability of infusions devices in both the inpatient and outpatient settings. Infusion regimens can include a basal infusion only, an intermittent bolus dosing only, and a combination of a basal infusion with a patient-controlled bolus dosing. Although there are limited data on which to base recommendations on the optimal basal rate, bolus volume, and lockout period, the majority of studies indicate that a lower basal infusion in conjunction with a patient controlled bolus dose provides the optimal method of delivery, as it provides equivalent analgesia but with a lower total LA dose compared to continuous infusions with higher basal rates. The technique of continuous block or specifically patient-controlled regional anesthesia (PCRA) has been used for brachial plexus, interscalene block, and femoral nerve block. After total hip or knee arthroplasty, PCRA techniques reduce the LA consumption without compromise in patient satisfaction or pain scores in comparison with continuous infusions. Recent randomized double-blinded, placebo-controlled trials provided data involving patients discharged at home with CPNB. These studies included patients scheduled for procedures that had had an infraclavicular,47 interscalene,48 or posterior sciatic popliteal perineural catheter.49 Patients receiving perineural LA infusions achieved clinically lower resting and breakthrough pain scores while requiring fewer oral analgesics. Patients who received perineural LA, and specifically those receiving PCRA, experienced additional benefits related to improved analgesia. Between 0 and 30% of patients with perineural ropivacaine reported insomnia due to pain as compared with 60–70% of patients using only oral opioids. Patients receiving perineural ropivacaine infusion woke up from sleep because of breakthrough pain episodes an average of zero times on the first postoperative night compared with two times for patients receiving perineural saline. Obviously, lower opioid consumption in patients receiving perineural LA resulted in fewer opioid-related side-effects. Patients receiving perineural LA also reported greater satisfaction with their postoperative analgesia, with scores of 8.8–9.8 compared with 5.5–7.7 for patients receiving placebo.47–49 The benefits of such analgesia appear to be substantiated by fewer hospital readmissions in the continuous PNB group. Capdevila et al. compared CPNB infusions of ropivacaine (0.2%), either as a continuous infusion or PCRA, with PCA intravenous morphine in 83 patients scheduled for ambulatory orthopedic surgery for functional recovery and postoperative analgesia.50 Basal–bolus ropivacaine infusion (PCRA) decreased the time to commencing a 10 min walk, optimized all daily activities, and decreased the amount of ropivacaine used. The PCA morphine group had greater pain scores and consumption of breakthrough morphine and ketoprofen as compared with the ropivacaine group. The incidence of nausea/vomiting, sleep disturbance, and dizziness increased, and the patient satisfaction score decreased in the PCA morphine group. After ambulatory orthopedic surgery, ropivacaine (0.2%) delivered as a PCRA infusion optimizes functional recovery and pain relief. Recently in postoperative popliteal sciatic nerve block patients, Taboada and colleagues reported that LA administered as a new automated regular bolus in conjunction with PCRA provided similar pain relief as a continuous infusion technique combined with PCRA.49 Furthermore, the new dosing regimen reduced the need for additional PCRA and the overall consumption of local anesthetic.

Electronic infusion pumps provide highly accurate and consistent basal rates over the entire infusion duration but are costly and need to be returned to the healthcare unit if used in the ambulatory setting. Elastomeric devices can provide a higher or lower-than-expected basal rate with an error rate of ± 20%.51 There are insufficient published data to determine the clinical situations in which the typical basal rate variation of elastomeric pumps would be clinically relevant. Elastomeric pumps are cheaper per unit price but are disposable. These pumps are also less technically challenging than electronic pumps, with no alarms or complex programming. In some trials, patients prefer elastomeric pumps due to this simplicity despite the fact that there is no warning if a catheter occlusion or pump malfunction occurs.52 Investigators have utilized elastomeric pumps for multiple catheter locations and surgical procedures. Pumps allow for both PCRA boluses and a basal infusion, while others allow a basal rate only. Without the option for a bolus dose, higher doses of oral opiates are often required for break through pain. The infusion can be tailored to provide a minimum basal rate allowing maximum infusion duration and minimal motor block, yet allow bolus dosing for physical therapy.

While the use of USG in regional anesthesia has prompted a revolution in how we approach single-shot PNB, data concerning its use for ambulatory CPNB are sparse. In theory, USG has the potential to confirm catheter tip location (direct visualization of the catheter tip or indirectly by visualizing LA spread). Only two large prospective observational studies in ambulatory patients demonstrated the effectiveness of USG as the primary modality (with or without needle nerve stimulation) to place peripheral nerve catheters.53,54 Both studies reported that 98% of catheters provided optimal postoperative analgesia with a low incidence of minor side-effects (complications rate was 0.4%). The first attempt catheter success rate was 96%. There were few interventions requiring an anesthesiologist or a dedicated nurse, as patients had access to 24-hour telephone advice via a contact person for any questions or problems they might have had.

1 Pavlin JD, Kent CD. Recovery after ambulatory anesthesia. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2008;21(6):729-735.

2 Williams BA, Kentor ML. Making an ambulatory surgery centre suitable for regional anaesthesia. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2002;16(2):175-194.

3 Gebhard RE. Outpatient regional anesthesia for upper extremity surgery. International Anesthesiology Clinics. Regional Anesthesia for Ambulatory Surgery. 2005;43(3):177-183.

4 Armstrong KP, Cherry RA. Brachial plexus anesthesia compared to general anesthesia when a block room is available. Can J Anaesth. 2004;51(1):41-44.

5 Sandberg WS, Daily B, Egan M, et al. Deliberate perioperative systems design improves operating room throughput. Anesthesiology. 2005;103(2):406-418.

6 Felice K, Schumann H. Intravenous lipid emulsion for local anesthetic toxicity: a review of the literature. J Med Toxicol. 2008;4(3):184-191.

7 Casati A, Danelli G, Baciarello M, et al. A prospective, randomized comparison between ultrasound and nerve stimulation guidance for multiple injection axillary brachial plexus block. Anesthesiology. 2007;106(5):992-996.

8 Williams SR, Chouinard P, Arcand G, et al. Ultrasound guidance speeds execution and improves the quality of supraclavicular block. Anesth Analg. 2003;97(5):1518-1523.

9 Boezaart AP. Continuous interscalene block for ambulatory shoulder surgery. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2002;16(2):295-310.

10 McCartney CJ, Brull R, Chan VW, et al. Early but no long-term benefit of regional compared with general anesthesia for ambulatory surgery. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:461-467.

11 Aldrete JA. The post anesthesia recovery score revisited. J Clin Anesth. 1995;7:89-91.

12 Chung F, Chan VW, Ong D. A post-anesthetic discharge scoring system for home readiness after ambulatory surgery. J Clin Anesth. 1995;7(6):500-506.

13 Klein SM, Nielsen KC, Greengrass RA, et al. Ambulatory discharge after long-acting peripheral nerve blockade: 2382 blocks with ropivacaine. Anesth Analg. 2002;94(1):65-70.

14 Brull R, McCartney CJ, Chan VW, et al. Effect of transarterial axillary block versus general anesthesia on paresthesiae 1 year after hand surgery. Anesthesiology. 2005;103(5):1104-1105.

15 Neal JM, Bernards CM, Hadzic A, et al. ASRA Practice Advisory on Neurologic Complications in Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2008;33(5):404-415.

16 Koscielniak-Nielsen ZJ, Rasmussen H, Nielsen PT. Patients’ perception of pain during axillary and humeral blocks using multiple nerve stimulations. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2004;29(4):328-332.

17 Julien RE, Williams BA. Regional anesthesia procedures for outpatient shoulder surgery. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2005;43(3):167-175.

18 Hadzic A, Williams BA, Karaca PE, et al. For outpatient rotator cuff surgery, nerve block anesthesia provides superior same-day recovery over general anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 2005;102(5):1001-1007.

19 Ilfeld BM, Morey TE, Wright TW, et al. Continuous interscalene brachial plexus block for postoperative pain control at home: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study. Anesth Analg. 2003;96(4):1089-1095.

20 Ilfeld BM, Vandenborne K, Duncan PW, et al. Ambulatory continuous interscalene nerve blocks decrease the time to discharge readiness after total shoulder arthroplasty: a randomized, triple-masked, placebo-controlled study. Anesthesiology. 2006;105(5):999-1007.

21 Mayfield JB, Carter C, Wang C, Warner JJ. Arthroscopic shoulder reconstruction: fast-track recovery and outpatient treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;390:10-16.

22 Borgeat A, Perschak H, Bird P, et al. Patient-controlled interscalene analgesia with ropivacaine 0.2% versus patient-controlled intravenous analgesia after major shoulder surgery: effects on diaphragmatic and respiratory function. Anesthesiology. 2000;92(1):102-108.

23 Riazi S, Carmichael N, Awad I, et al. Effect of local anaesthetic volume (20 vs 5 ml) on the efficacy and respiratory consequences of ultrasound-guided interscalene brachial plexus block. Br J Anaesth. 2008;101(4):549-556. Epub 2008 Aug 4

24 Brown AR. Anaesthesia for procedures of the hand and elbow. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2002;16(2):227-246.

25 Hadzic A, Arliss J, Kerimoglu B, et al. A comparison of infraclavicular nerve block versus general anesthesia for hand and wrist day-case surgeries. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:127-132.

26 Thomson CJ, Lalonde DH. Randomized double-blind comparison of duration of anesthesia among three commonly used agents in digital nerve block. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118:429-432.

27 Wilhelmi BJ, Blackwell SJ, Miller JH, et al. Do not use epinephrine in digital blocks: myth or truth? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107:393-397.

28 Cummings AJ, Tisol WB, Meyer LE. Modified transthecal digital block versus traditional digital block for anesthesia of the finger. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2004;29:44-48.

29 Klein SM, Pietrobon R, Nielsen KC, et al. Peripheral nerve blockade with long-acting local anesthetics: a survey of the Society for Ambulatory Anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 2002;94:71-76.

30 Ilfeld BM, Gearen PF, Enneking FK, et al. Total hip arthroplasty as an overnight-stay procedure using an ambulatory continuous psoas compartment nerve block: a prospective feasibility study. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2006;31:113-118.

31 Ilfeld BM, Ball ST, Gearen PF, et al. Ambulatory continuous posterior lumbar plexus nerve blocks after hip arthroplasty: a dual-center, randomized, triple-masked, placebo-controlled trial. Anesthesiology. 2008;109:491-501.

32 Chelly JE, Ben-David B, Joshi RM, et al. Minimally invasive total hip replacement as an ambulatory procedure. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2005;43:161-165.

33 Mears DC, Mears SC, Chelly JE, et al. THA with a minimally invasive technique, multi-modal anesthesia, and home rehabilitation: factors associated with early discharge? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(6):1412-1417.

34 Hadzic A, Karaca PE, Hobeika P, et al. Peripheral nerve blocks result in superior recovery profile compared with general anesthesia in outpatient knee arthroscopy. Anesth Analg. 2005;100:976-981.

35 Jankowski CJ, Hebl JR, Stuart MJ, et al. A comparison of psoas compartment block and spinal and general anesthesia for outpatient knee arthroscopy. Anesth Analg. 2003;97:1003-1009.

36 Bonicalzi V, Gallino M. Comparison of two regional anesthetic techniques for knee arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 1995;11(2):207-212.

37 Goranson BD, Lang S, Cassidy JD, et al. A comparison of three regional anaesthesia techniques for outpatient knee arthroscopy. Can J Anaesth. 1997;44(4):371-376.

38 Casati A, Cappelleri G, Berti M, et al. Randomized comparison of remifentanil-propofol with a sciatic-femoral nerve block for out-patient knee arthroscopy. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2002;19(2):109-114.

39 Mulroy MF, Larkin KL, Batra MS, et al. Femoral nerve block with 0.25% or 0.5% bupivacaine improves postoperative analgesia following outpatient arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament repair. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2001;26:24-29.

40 Iskandar H, Benard A, Ruel-Raymond J, et al. Femoral block provides superior analgesia compared with intra-articular ropivacaine after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2003;28:29-32.

41 Williams BA, Kentor ML, Vogt MT, et al. Femoral-sciatic nerve blocks for complex outpatient knee surgery are associated with less postoperative pain before same-day discharge: a review of 1,200 consecutive cases from the period 1996–1999. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:1206-1213.

42 Ilfeld BM, Le LT, Meyer RS, et al. Ambulatory continuous femoral nerve blocks decrease time to discharge readiness after tricompartment total knee arthroplasty: a randomized, triple-masked, placebo-controlled study. Anesthesiology. 2008;108:703-713.

43 McLeod DH, Wong DH, Vaghadia H, et al. Lateral popliteal sciatic nerve block compared with ankle block for analgesia following foot surgery. Can J Anaesth. 1995;42:765-769.

44 McLeod DH, Wong DH, Claridge RJ, Merrick PM. Lateral popliteal sciatic nerve block compared with subcutaneous infiltration for analgesia following foot surgery. Can J Anaesth. 1994;41:673-676.

45 White PF, Issioui T, Skrivanek GD, Early JS, et al. The use of a continuous popliteal sciatic nerve block after surgery involving the foot and ankle: does it improve the quality of recovery? Anesth Analg. 2003;97:1303-1309.

46 Ilfeld BM, Thannikary LJ, Morey TE, et al. Popliteal sciatic perineural local anesthetic infusion: a comparison of three dosing regimens for postoperative analgesia. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:970-977.

47 Ilfeld BM, Morey TE, Enneking FK. Infraclavicular perineural local anesthetic infusion: a comparison of three dosing regimens for postoperative analgesia. Anesthesiology. 2004;100:395-402.

48 Ilfeld BM, Morey TE, Wright TW, et al. Continuous interscalene brachial plexus block for postoperative pain control at home: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study. Anesth Analg. 2003;96:1089-1095.

49 Taboada M, Rodríguez J, Bermudez M, et al. Comparison of continuous infusion versus automated bolus for postoperative patient-controlled analgesia with popliteal sciatic nerve catheters. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:150-154.

50 Capdevila X, Dadure C, Bringuier S, et al. Effect of patient-controlled perineural analgesia on rehabilitation and pain after ambulatory orthopedic surgery: a multicenter randomized trial. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:566-573.

51 Ilfeld BM, Morey TE, Enneking FK. Portable infusion pumps used for continuous regional analgesia: delivery rate accuracy and consistency. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2003;28:424-432.

52 Capdevila X, Macaire P, Aknin P, et al. Patient-controlled perineural analgesia after ambulatory orthopedic surgery: a comparison of electronic versus elastomeric pumps. Anesth Analg. 2003;96:414-417.

53 Fredrickson MJ, Ball CM, Dalgleish AJ. Successful continuous interscalene analgesia for ambulatory shoulder surgery in a private practice setting. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2008;33:122-128.

54 Swenson JD, Bay N, Loose E, et al. Outpatient management of continuous peripheral nerve catheters placed using ultrasound guidance: an experience in 620 patients. Anesth Analg. 2006;103:1436-1443.

Mulroy MF, McDonald SB. Regional anesthesia for outpatient surgery. Anesthesiol Clin North America. 2003;21(2):289-303.

O’Donnell BD, Iohom G. Regional anesthesia techniques for ambulatory orthopedic surgery. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2008;21(6):723-728.

Liu SS, Strodtbeck WM, Richman JM, Wu CL. A comparison of regional versus general anesthesia for ambulatory anesthesia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Anesth Analg. 2005;101(6):1634-1642.

Arakawa M. Central neuraxial blockade in ambulatory surgery. J Anesth. 2003;17(2):149.

Mulroy MF, Salinas FV. Neuraxial techniques for ambulatory anesthesia. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2005;43(3):129-141.