CHAPTER 11 Peripheral Compartment Approach to Hip Arthroscopy

Introduction

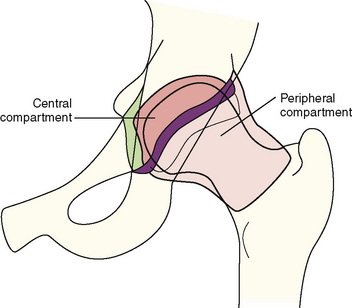

The hip is divided arthroscopically into two compartments that are separated by the labrum (Figure 11-1). The first is the central compartment (CC), which comprises the lunate cartilage; the acetabular fossa; the ligamentum teres; and the loaded articular surface of the femoral head. This part of the joint can be visualized almost exclusively with traction. The second is the PC, which consists of the unloaded cartilage of the femoral head; the femoral neck, with the medial, anterior, and posterolateral synovial folds (i.e., Weitbrecht ligaments); and the articular capsule with its intrinsic ligaments, including the zona orbicularis. This area can be better seen without traction.

Indications

In addition, the PC allows access to periarticular structures such as the following:

History and physical examination

The most important thing to do during the primary preoperative workup is to determine whether the source of pain is intra-articular or extra-articular. This determination can be made by going through a thorough diagnostic checklist (see Chapter 3: Imaging: Plain Radiographs and Chapter 6: The Technique and Art of the Physical Examination of the Adult and Adolescent Hip).

Surgical technique

Positioning and Switching Between the Compartments

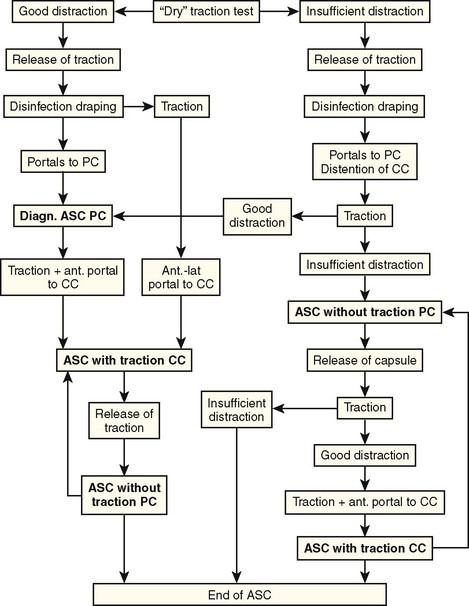

To allow for a complete diagnostic arthroscopic examination of the hip, both techniques with and without traction are combined for arthroscopy of the CC and the PC; this requires specific attention to positioning, table equipment, and draping. The order of arthroscopy with and without traction depends on different parameters (Figure 11-2). In “standard” cases with good distraction and visibility, we prefer to access the PC first to control portal placement to the CC. However, there are cases in which the distraction of the hip is insufficient and visibility in the PC decreased. Here, a release of different parts of the joint capsule can be performed to increase the PC space and improve distraction. We usually start with a release of the zona orbicularis that extends into the iliofemoral ligament in cases of severe capsular thickening or fibrosis, and this is followed by therapeutic procedures such as the reshaping of the head–neck junction. At this point, traction is again applied. If distraction is improved, portals to the CC can be placed under arthroscopic control. However, if distraction is still not sufficient, arthroscopy of the PC only should be considered to avoid iatrogenic damage of the acetabular labrum and the femoral head cartilage during portal placement to the CC.

During the past several years, we have removed the foot from the traction module to allow for the maximum range of movement. However, this technique is time consuming and strenuous for the assistant who is holding the leg. In addition, switching back into the CC under traction is difficult, because the foot needs to be readapted to the traction module. Especially for femoroacetabular impingement cases, there is a need to alternate between both compartments with and without traction. Thus, we changed our technique. For arthroscopy of the PC, the foot is kept in the traction module. The traction is released, and the traction module with the foot is slid in with the extension bar. With this technique, the hip and knee can be flexed up to 90 degrees, abducted to about 30 degrees, and rotated 20 degrees internally and externally (Figure 11-3). When reentering the CC, the extension boom is drawn out, and the hip and knee are extended. Before traction is applied, the room nurse has to check for possible soft-tissue entrapment at the perineum.

Portals to the Peripheral Compartment

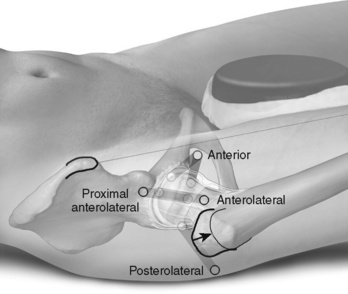

A comprehensive overview of the PC can be obtained from the proximal anterolateral portal only (Figure 11-4). At this level, the soft-tissue mantle is relatively thin, and the position of the portal is near the lateral cortex of the femoral head. Therefore, the maneuverability of the arthroscope is sufficient for moving it into the medial recess, gliding over the anterior surface of the femoral head to the lateral recess, and passing the lateral cortex of the femoral neck for the inspection of the posterolateral recess. With the need for better access to the lateral and posterolateral head and neck area for therapy of the cam type of femoroacetabular impingement and the removal of chondromas from the medial area underneath the transverse ligament in patients with synovial chondromatosis, a two-portal technique for the PC is usually preferred.

Figure 11–4 Portals to the peripheral compartment of the hip.

From Dienst M (Ed). Hip arthroscopy. Elsevier Urban & Fischer, Munich; 2009.

Proximal Anterolateral Portal

The position and direction of the proximal anterolateral portal are different for the anterolateral portal to the CC in that the incision lies more proximally and anteriorly. Usually the perfect spot for the skin incision can be found by palpating a soft spot one third of the distance along a line drawn from the anterior superior iliac spine to the tip of the greater trochanter. Here, one can feel the anterior margin of the gluteus medius. On its way to the joint capsule, the needle only penetrates the tensor fasciae latae. Under fluoroscopy, the needle is directed perpendicular to the femoral neck axis to the anterolateral transition from the femoral head to the neck (Figure 11-5). The proximal anterolateral portal is predominantly used as a viewing portal. However, in patients with femoroacetabular cam impingement, this portal becomes important for the removal of the lateral and posterolateral extension of the head–neck bump.

Special Equipment for Arthroscopy of the Peripheral Compartment

Operating Table and Devices

The PC can be viewed with an arthroscope on a regular basic operating table with the patient in the supine or the lateral position. However, the need for arthroscopy of the CC in many cases requires the option of distracting the hip joint. The big advantage of a standard fracture table is its stable application of traction. For the combination with arthroscopy without traction, the extension booms must have the option of gliding in and out during arthroscopy to flex and extend the hip and knee joints (see Figure 11-3). The position of abduction and rotation needs to be adjustable. In particular, the option for lengthening and shortening the extension booms depends on the height of the patient. It is important to check before disinfection and draping if enough hip flexion can be achieved or if additional lengthening or shortening adapters are needed. During the past several years, alternative devices have been developed. In general, they provide similar functions with somewhat less effective traction but somewhat better motion during the nontraction part of the procedure.

Diagnostic Round and Arthroscopic Anatomy of the Peripheral Compartment

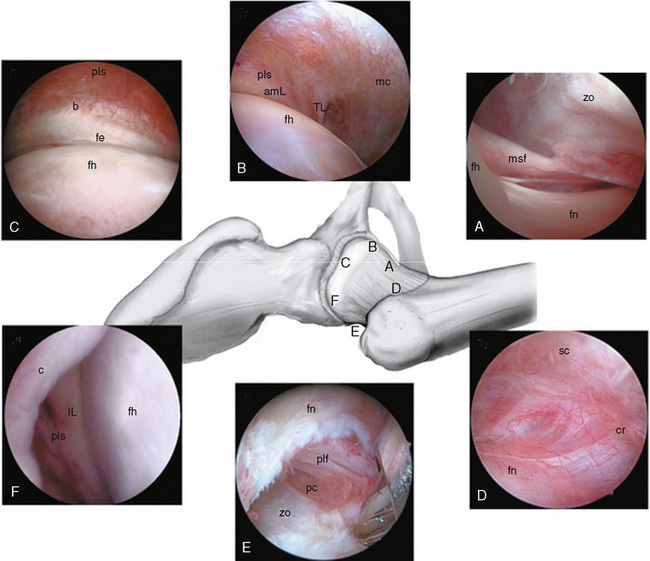

The PC can be divided into seven zones: 1) the anterior neck area; 2) the medial neck area; 3) the medial head area; 4) the anterior head area; 5) the lateral head area; 6) the lateral neck area; and 7) the posterior area. During a diagnostic round trip, the PC can best be viewed starting from the anterior surfaces of the femoral neck (Figure 11-6).

The Peripheral Compartment as an Intermediate Space for Safe Access to the Central Compartment

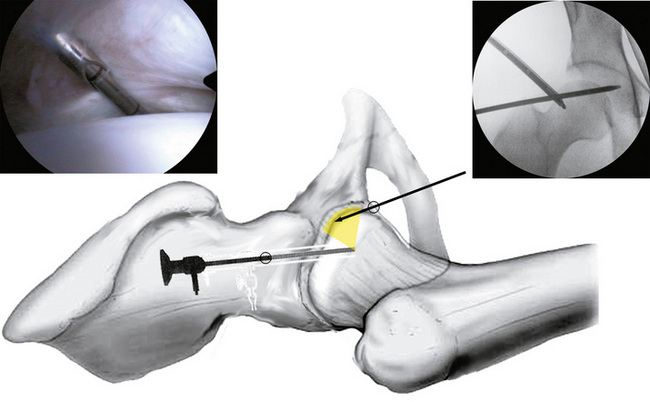

Direct arthroscopic access to the CC is technically demanding. In addition, particularly for the arthroscopic surgeon who is less experienced with this procedure, the acetabular labrum and cartilage of the femoral head are at risk for iatrogenic injury. Thus, we prefer to access the PC first and to then control the first portal placement to the CC via arthroscopic means from the PC (Figure 11-7).

The hip is placed in 10 degrees of flexion, neutral rotation, and 0 degrees to 10 degrees of abduction, with the knee straight. Without traction, the PC is accessed via the proximal anterolateral portal. The anterior head area is inspected. Under arthroscopic control, the anterior portal to the CC is placed. As soon as the guidewire is passed underneath the labrum (see Figure 11-7), traction is applied, and the wire is advanced into the acetabular fossa. The arthroscope is exchanged with an irrigation cannula via the proximal anterolateral portal, and the arthroscope is introduced via the anterior portal into the CC. At this point, additional portal placement to the CC (anterolateral and posterolateral) can be controlled arthroscopically.

Complications

Byrd J.W.T., Pappas J.N., Pedley M.J. Hip arthroscopy: an anatomic study of portal placement and relationship to the extra-articular structures. Arthroscopy. 1995;11:418-423.

Dienst M., Gödde S., Seil R., et al. Hip arthroscopy without traction: in vivo anatomy of the peripheral hip joint cavity. Arthroscopy. 2001;17:924-931.

Dienst M., Seil R., Kohn D. Safe arthroscopic access to the central compartment of the hip joint. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:1510-1514.

Dorfmann H., Boyer T. Arthroscopy of the hip: 12 years of experience. Arthroscopy. 1999;15:67-72.

Dorfmann H., Boyer T., Henry P., DeBie B. A simple approach to hip arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 1988;4:141-142.

Gautier E., Ganz K., Krügel N., et al. Anatomy of the medial femoral circumflex artery and its surgical implications. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82-B:679-683.

Klapper R.C., Silver D.M. Hip arthroscopy without traction. Contemp Orthop. 1989;18:687-693.

Wettstein M., Jung J., Dienst M. Arthroscopic psoas tenotomy. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:907.e1-907.e4.