68 Peripheral Arterial Disease

• Intermittent claudication is the earliest clinical manifestation of pathologically significant peripheral arterial disease.

• The ankle-brachial index can help confirm clinical suspicion of occlusive arterial disease.

• Ischemic rest pain signals critical, limb-threatening disease.

• The classic manifestation of acute arterial occlusion is described by the six “P’s”: pain, polar (cold), paresthesia, paralysis, pallor, and pulselessness.

• Treatment of nonischemic peripheral arterial disease consists of modification of risk factors, exercise programs, and medications aimed at platelet inhibition.

• Prompt initiation of therapy is the most important aspect of the treatment of acute limb ischemia, and patients should receive a heparin bolus followed by an infusion, ideally even before diagnostic testing is begun.

• Treatment of ischemic peripheral arterial disease depends on whether the extremity is viable (angiography to assess the extent of disease), nonviable (primary amputation), or threatened (immediate surgical intervention required).

Epidemiology

The most common term used to describe atherosclerotic vascular disease of the lower extremities is peripheral arterial disease (PAD). In North America and Europe, it is estimated that 27 million individuals are affected by PAD. In a significant proportion of patients the disease is occult but is nevertheless an important indicator of significant cardiovascular events.1,2 Systemic atherosclerotic disease with damage to end-organs other than the heart continues to be associated with high morbidity and mortality,3 and surprisingly little research is being done on it.

By 50 years of age the prevalence of PAD is 2% to 3%, and it rises to 20% in those older than 75 years.4 The clinical findings of PAD in patients older than 50 years is as follows: 10% to 35% have classic claudication, 20% to 50% are asymptomatic, 40% to 50% have atypical leg pain, and the remaining 1% to 2% have critical ischemia.5,6 Women have a relative risk of 0.7 in comparison with men. African American subjects have the highest risk for PAD (2.5) relative to the white population, followed by Hispanic subjects (1.5).

Box 68.1 lists the risk factors for PAD.6 They are similar to the risk factors that promote the development of coronary atherosclerosis. The risk factor with the highest correlation to PAD is cigarette smoking. When compared with nonsmokers, smokers have a 1.7- to 5.6-fold increase in the development and progression of atherosclerosis in the peripheral vasculature.7 In patients with symptomatic PAD, smoking increases this risk 8 to 10 times.8 Risk increases in a powerful dose-dependent manner according to the number of cigarettes smoked per day and the number of years of smoking. Diabetes increases the risk for PAD, 3.5 times in men and 8.6 times in women.9 Diabetic patients are also 7 to 15 times more likely to require amputation. The Framingham Heart Study found that risk for the development of intermittent claudication was 2.5-fold and 4-fold higher in men and women, respectively, who had hypertension and that this risk was proportional to the severity of the hypertension.9 Genetic predisposition represents an important risk factor for atherosclerosis, and such predisposition accounts for as much as 50% of the risk in some studies.10 Patients who have PAD also have a high incidence of coronary heart disease (CHD), and in general, patients have a two to four times higher incidence of CHD and cerebrovascular disease if PAD is also present.7

Box 68.1 Risk Factors for Lower Extremity Peripheral Arterial Disease

Age 50 to 69 years with a history of smoking or diabetes

Age younger than 50 years with diabetes and one other atherosclerotic risk factor (smoking, dyslipidemia, hypertension, or hyperhomocysteinemia)

Leg symptoms with exertion (suggestive of claudication) or ischemic rest pain

Abnormal lower extremity pulse findings

Known atherosclerotic coronary, carotid, or renal artery disease

Pathophysiology

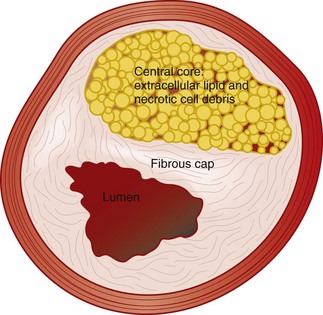

Atherosclerosis was originally thought to be primarily lipoprotein accumulation but is now better understood, fundamentally, as chronic inflammatory disease of the arterial system.11 The inflammatory process leads to plaque disruption and thrombosis, and the plaques that are vulnerable are characterized by a large lipid core, a thin fibrous cap, and inflammatory cells at the thinnest portion of the cap surface (Fig. 68.1).12 Plaque rupture has been shown to be critical in the development of acute coronary syndromes, but the importance of this event in patients with PAD is not known at this time.

The vascular smooth muscle cell is important in the development of atherosclerosis. Once activated, the cell migrates into the intima and begins to proliferate and secrete matrix proteins and enzymes. This step has been shown to be important in the development of stenosis both in the atherosclerotic vessel and in vessels that have been stented.13 In addition, the vessel often constricts rather than dilates, thereby narrowing the lumen even more.14 Progression of PAD can result from worsening local atherosclerotic disease or a superimposed embolic, thrombotic, inflammatory, traumatic, or vasospastic event.

Thromboembolism

More than 80% of arterial emboli originate in the heart and travel to the extremities, the lower extremities being much more frequently affected than the upper ones. Emboli typically lodge in places with acute narrowing of the artery, such as an atherosclerotic plaque or a point where the vessel branches. The frequencies with which emboli lodge in various areas are as follows15: femoral arteries, 28%; arm vessels, 20%; aortoiliac vessels, 18%; popliteal arteries, 17%; and visceral vessels, 9%.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

The clinical signs and symptoms of PAD may be nonspecific and be manifested in a variable fashion according to degree and location of the atherosclerotic disease, as well as the presence of other previously described pathologic processes, such as thromboemboli, atheroemboli, inflammation, trauma, and vasospasm. The clinical spectrum ranges from a nonspecific systemic illness to a catastrophic event such as an ischemic leg. The gastrointestinal tract is an often-overlooked area of involvement that has been shown to be involved in about a fifth of cases. Patients may complain of nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, melena, or hematochezia. Stools may be heme positive, and intestinal ischemia can progress to infarction in some cases. Skin manifestations are the most common finding in patients with PAD and appear in approximately a third of cases.16 Livedo reticularis is a red-blue netlike mottling of the skin and represents embolization to the skin. Such mottling is generally seen on the legs, buttocks, and thighs and rarely involves the arms.

Key components of the vascular review of symptoms and family history are listed in Box 68.2. Physical findings in patients with PAD are listed in Box 68.3. Despite general relationships between PAD and the site of pain, the history and physical examination are not reliable for the detection of lower extremity PAD. Relying solely on the presence of classic claudication will miss up to 90% of cases.5,6 Physical examination can also be unreliable. For instance, an abnormal femoral pulse has high specificity and positive predictive value but low sensitivity for large-vessel disease. The best single discriminator is an abnormal posterior tibial pulse.17

Box 68.2 Key Findings in the Vascular Review of Systems

Any exertional limitation of the lower extremity muscles or any history of walking impairment (fatigue, aching, numbness, or pain). The primary site or sites of discomfort in the buttock, thigh, calf, or foot should be recorded along with the relationship of such discomfort to rest or exertion

Any poorly healing or nonhealing wounds on the legs or feet

Any pain at rest localized to the lower part of the leg or foot and its association with the upright or recumbent positions

Postprandial abdominal pain that is reproducibly provoked by eating and is associated with weight loss

Box 68.3 Key Components of the Vascular Physical Examination in a Patient with Possible Peripheral Arterial Disease

Measurement of blood pressure in both arms and notation of any interarm asymmetry

Palpation of the carotid pulses and notation of carotid upstroke and amplitude and the presence of bruits

Auscultation of the abdomen and flank for bruits

Palpation of the abdomen and notation of the presence of aortic pulsation and the maximum diameter of the aorta

Palpation of pulses at the brachial, radial, ulnar, femoral, popliteal, dorsalis pedis, and posterior tibial sites

Auscultation of both femoral arteries for the presence of bruits

Assessment of pulse intensity, which should be recorded numerically as follows: 0, absent; 1, diminished; 2, normal; 3, bounding

Inspection of the feet for evaluation of color, temperature, and integrity of the skin and intertriginous areas and recording of the presence of ulceration

Documentation of the presence of symmetry, edema, and venous distention of the lower extremities

Recording of additional findings suggestive of severe peripheral arterial disease, including distal hair loss, trophic skin changes, and hypertrophic nails

Acute Arterial Occlusion

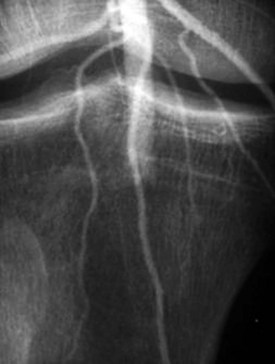

Patients with acute arterial occlusion commonly complain of a sudden onset of pain and coldness distally, on the side of the occlusion (Fig. 68.2). As the ischemia progresses, the classic findings of acute arterial occlusion become evident, as described by the six “P’s”: pain, polar (cold) sensation, paresthesia, paralysis, pallor, and pulselessness. As the peripheral nerves become ischemic, paresthesias, numbness, and then paralysis develop sequentially. The sensory peripheral nerves are affected first, with decreases in proprioception and light touch, and then the larger pain and motor fibers become involved and give rise to a loss of sensation, weakness, and paralysis. Paralysis is usually a bad prognostic sign for reversibility of the ischemia. Signs of ischemia can be seen distal to the level of arterial occlusion. During the first 8 hours after the ischemic insult, the extremity looks pale because of the spastic nature of the arterial tree surrounding the region. Twelve to 24 hours after the injury, the extremity may become cyanotic and mottled. As arterial flow ceases, venous drainage also slows or stops, thereby leading to profound stasis, which further aggravates the damage. On careful examination, the cold part of the extremity can easily be demarcated from its warmer proximal portion. The ischemia is unlikely to be reversible if the affected limb is paralyzed.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

Once the clinician is convinced that the patient’s symptoms are related to PAD, the first priority is to determine whether the symptoms represent PAD without occlusion (nonischemic) or whether ischemic PAD is present. The next step is to determine whether the extremity is viable, threatened, or nonviable (Box 68.4). When arterial blood flow is insufficient to meet the metabolic demands of resting muscle or tissue, limb-threatening ischemia results. This is the most common indication for emergency arterial reperfusion. The selected group of patients requires immediate assessment of their vascular system. Arteriography provides the most useful information in the setting of acute arterial occlusion because in addition to providing information on anatomy, it can distinguish between embolism and thrombosis. Embolism has a sharp cutoff of contrast agent with a reverse meniscus sign; thrombosis usually has a more tapered cutoff. Diffuse atheromatous disease is also usually found around a thrombotic occlusion.

Box 68.4 Categories of Acute Limb Ischemia

Viable: The extremity is not immediately threatened. The patient does not complain of ischemic rest pain, no neurologic deficit is present, and the capillary circulation in the skin appears to be adequate. Physical examination demonstrates pulses with either palpation or a Doppler flowmeter.

Threatened viability: Reversible ischemia has occurred, and the extremity is salvageable without major amputation if the arterial obstruction is relieved promptly. Affected patients have ischemic rest pain with mild transient or incomplete neurologic symptoms. The pulses are not detected with a Doppler flowmeter.

Nonviable (major, irreversible ischemic change): Major amputation of the affected limb is frequently required. Affected patients have profound sensory loss and muscle paralysis, absence of capillary flow, or evidence of more advanced ischemia (muscle rigor or marbled skin). No pulses can be palpated or detected with a Doppler flowmeter.

Acute Arterial Occlusion

Acute arterial occlusion (critical limb ischemia) is defined as a sudden decrease in limb perfusion that causes a potential threat to limb viability in patients seen within 2 weeks of the acute event.18 Acute arterial occlusion can be the result of emboli from a distant source, thrombosis of a previously patent artery, or direct trauma to an artery (Box 68.5).

Anke-Brachial Index

Because blood flow is diminished, the most common sensor used is the Doppler flowmeter. Calculation of the ankle-brachial index (ABI) is an accurate way to diagnose PAD. The ABI is a simple and relatively inexpensive test to confirm the clinical suspicion of occlusive arterial disease, and it provides a measure of the severity of the peripheral vascular disease.19 The ABI is calculated by measuring systolic blood pressure with a Doppler probe in the brachial, posterior tibial, and dorsalis pedis arteries. The highest of the measurements in the ankle and foot is divided by the highest in the upper extremity. The ABI in normal individuals is 1.0 or greater; values higher than 1.3 usually indicate a calcified vessel that is noncompressible. An ABI of less than 0.9 has 95% sensitivity (100% specificity) for PAD and is associated with 50% or greater stenosis in one or more major vessels (Box 68.6).

Box 68.6 Ankle-Brachial Index Measurements

1. Arm systolic pressure should always be measured with a Doppler flowmeter because measurement by auscultation can be inaccurate.

2. Pressure must be recorded in both arms and both tibial arteries at the ankle.

3. Systolic pressure is measured at the point at which flow is first detected, not at the point at which it is lost during inflation.

4. The absolute levels of blood pressure and the ankle-brachial index are then measured.

Imaging

Duplex Ultrasonography

The term duplex ultrasonography refers to B-mode real-time imaging and pulsed Doppler analysis of the velocity of flowing blood in arteries and veins. Arterial duplex ultrasonography provides a “road map” of stenosis of the arteries of the lower extremities. The sensitivity of duplex ultrasonography in detecting occlusions and stenosis is 95%, with a specificity of 98%.20 The utility of performing duplex ultrasonography in the emergency department is limited because most decisions about patient care are based on the history and physical findings.

Computed Tomographic Angiography

Computed tomographic angiography (CTA) is a vascular imaging technique that can be used to assess many vascular diseases rapidly and safely. Multidetector computed tomography can provide very high-quality resolution in comparison with the single-detector scanners from the not-so-distant past. CTA has the following advantages over regular angiography: (1) the images can be reconstructed from multiple angles and in multiple planes, (2) soft tissues and other anatomic structures are better identified, and (3) the technique is less invasive with fewer complications and lower cost.1,21 CTA does, however, expose patients to radiation and potentially nephrotoxic dye loads. Because PAD is commonly multifocal, both arterial inflow and runoff should be imaged in their entirety. Studies have shown 100% concordance of CTA with angiography, as well as better visualization of other portions of distal vessels that are not seen with traditional angiography.1,21

Magnetic Resonance Angiography

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) of the peripheral vasculature can be performed quickly and accurately. MRA has two distinct advantages over CTA: its contrast agents are not nephrotoxic, and images are obtained without exposure to radiation. The quality of MRA is now so good that it has virtually surpassed angiography for evaluating stable patients with PAD to determine what type of intervention is most appropriate.22 MRA can assess not only vessel occlusion and stenosis but also the arterial wall for evidence of atherosclerosis.23 MRA investigations require prolonged study times and transport from the emergency department, thus limiting their usefulness in emergency situations.

Diagnostic Angiography

In digital subtraction angiography (DSA), the image is acquired, converted with an image intensifier, transferred to a monitor, and saved in digital format. DSA is a computer-assisted radiographic technique that subtracts images of bone and soft tissue to permit viewing of the cardiovascular system. Structures that do not change during injection are canceled out, which results in the “disappearance” of structures such as bone, soft tissues, and air. Improved hardware, software, and speed of the techniques combined with better outcomes from interventions mean that DSA is heavily relied on for vascular disease. The need for lower concentrations of iodinated contrast agents or the use of nonnephrotoxic agents also makes it a more desirable imaging technique than regular angiography.24 The major attributes of DSA that contribute to its importance are high resolution, ability to selectively evaluate individual vessels, and ability to access direct physiologic information from the tissues. Despite the diagnostic paradigm shift away from angiography, DSA is a cornerstone technology in PAD intervention and will probably remain so for the foreseeable future.19

Treatment

Prompt initiation of therapy is the most important aspect of the treatment of acute limb ischemia. Patients should immediately receive a heparin bolus followed by an infusion to prevent clot propagation and inhibit thrombosis distal to the lesion, where low flow or stasis is present. Heparin should be administered before diagnostic testing is performed.25,26 Subsequent therapy depends on whether the extremity is viable, threatened, or nonviable.

Patients with Viable Extremities

Patients found to have an ischemic but viable extremity on clinical examination should undergo urgent arteriography. Once the anatomy has been defined, vascular surgeons can determine whether surgical or intraarterial thrombolytic therapy is needed. One study reported limb salvage rates of approximately 70% with both thrombolytic therapy and surgical intervention in this patient population.27 The important thing for the emergency physician to remember is that thrombolytic therapy is limited by the length of time needed to dissolve the thrombus and the severity of the ischemia. Thrombolytics are given at the site of occlusion through the catheter used for angiography. This method has been shown to have a better outcome with fewer bleeding complications than is the case with intravenous administration. Both urokinase and tissue plasminogen activator have been studied and appear to be similar in outcome measures. Patients who have had ischemic symptoms for less than 14 days and are treated with thrombolytics have better amputation-free survival and shorter hospital stays than do those who undergo surgery; patients with ischemic symptoms for longer than 14 days have a better outcome with surgical intervention. In addition, in patients who have received thrombolytic therapy and eventually require surgical intervention, the magnitude of the surgical procedure is less than in patients who have not received thrombolytics.

The surgeon and interventional radiologist help determine the optimal therapy for a patient with limb ischemia and a viable extremity according to (1) the location and length of the lesion, (2) the cause (embolus versus thrombus), (3) the duration of symptoms, and (4) the suitability of the patient for surgery. In general, smaller, more distal emboli are best treated with thrombolytics, whereas a large embolus at a more proximal location is best treated by embolectomy27 (Figs. 68.3 and 68.4).

Patients with Threatened Extremities

Patients with threatened extremities should undergo immediate surgical revascularization.25 The vast majority of such patients have had an embolic event. Irreversible changes, including necrosis, may occur within 4 to 6 hours of the initial insult, thus leaving a fairly small therapeutic window. The small amount of time available makes thrombolytic therapy of limited utility27,28 (Figs. 68.5 and 68.6).

Fig. 68.6 Angiogram of the same patient as in Figure 68.5 after thrombectomy.

Note the resolution of flow and absence of visible clot (arrow).

Surgery usually reveals an embolus that can be removed by embolectomy. After embolectomy, most surgeons perform intraoperative arteriography to assess distal blood flow. If small distal emboli are found after embolectomy, intraoperative thrombolytic therapy may be considered. If the ischemia has been prolonged, compartment syndrome may result once blood flow is restored. Therefore, oral anticoagulation should be instituted after the procedure to prevent subsequent embolization.26

Patients with Nonviable Extremities

If clinical evaluation of a patient’s extremity reveals nonviability, amputation should proceed promptly.25 Angiography is not normally required to make this diagnosis, and the clinical findings dictate the level of amputation. In general, surgeons try to preserve as many joints as possible to decrease the work of ambulating with a prosthesis. If amputation is not performed in an expedient manner, the patient may have complications such as sepsis, acute renal failure, rhabdomyolysis, hyperkalemia, and cardiovascular collapse.

Follow-Up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

Of patients in whom PAD develops in association with symptoms of intermittent claudication, 70% to 80% will have stable symptoms at 5 years, with the remaining 10% to 20% having worsening claudication. Five percent to 10% will require revascularization in the subsequent 5-year period. Over the same interval, about 1% to 2% of patients will have critical leg ischemia, some of whom will require amputation.6,30 Predictors of progression include cigarette smoking, diabetes, high cholesterol, and hyperlipidemia.31 It should be noted that there is both wide geographic and wide ethnic variation in the outcome of PAD. White persons are more likely to undergo aortoiliac surgery and less likely to need lower extremity amputation than other ethnic groups are.32 This discrepancy cannot be explained by the higher prevalence of risk factors in other ethnic groups.

![]() Red Flags

Red Flags

Risk for peripheral arterial disease increases in a powerful dose-dependent manner with the number of cigarettes smoked per day and the number of years of smoking.

Ischemic fissures, decubitus ulcers of the ankles and heels, and ischemic ulcers correlate with arterial insufficiency.

More than one third of patients with embolic disease have skin manifestations, thus making them the most common physical finding.

In contrast to patients with ischemia pain, those with peripheral neuropathy usually have bilateral leg pain that is not relieved by dependency, as well as neurologic signs such as decreased deep tendon reflexes and loss of touch and vibratory sensation.

Attempts at limb salvage in a patient with hard neurologic findings indicative of prolonged ischemia may endanger the life of the patient because of the severe metabolic changes that occur after revascularization.

Acute extremity ischemia is associated with high rates of limb loss (30%) and hospital morbidity and mortality (20%).

![]() Patient Teaching Tips

Patient Teaching Tips

Physicians must educate patients on the importance of pain as a symptom of significant arterial disease and the need for immediate evaluation to save a limb.

Modification of risk factors, especially smoking, can not only arrest progression of the disease but may also, in some cases, reverse some of the clinical effects.

Patients with peripheral arterial disease must also undergo testing for associated coronary artery disease because of the close association of the two disease processes.

1 Norgren L, Hiatt WR, Dormandy JA, et al. Inter-Society Consensus for the Management of Peripheral Arterial Disease (TASC II). for the TASC II Working Group. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45(Suppl S):S5–S67.

2 Faxon DP, Creager MA, Smith SC, Jr., et al. Atherosclerotic Vascular Disease Conference: executive summary: Atherosclerotic Vascular Disease Conference proceeding for healthcare professionals from a special writing group of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2004;109:2595–2604.

3 Criqui MH, Langer RD, Fronek A, et al. Mortality over a period of 10 years in patients with peripheral arterial disease. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:381–386.

4 Selvin E, Erlinger TP. Prevalence of and risk factors for peripheral arterial disease in the United States: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999-2000. Circulation. 2004;110:738–743.

5 Hirsch AT, Criqui MH, Treat-Jacobson D, et al. Peripheral arterial disease detection, awareness, and treatment in primary care. JAMA. 2001;286:1317–1324.

6 Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. American Association for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions; Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology; Society of Interventional Radiology; ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines. ACC/AHA 2005 guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): a collaborative report from the American Associations for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, Society of Interventional Radiology, and the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Peripheral Arterial Disease): summary of recommendations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:1239–1312.

7 Criqui MH, Denenberg JO, Langer RD, et al. The epidemiology of peripheral arterial disease: importance of identifying the population at risk. Vasc Med. 1997;2:221–226.

8 Meijer WT, Hoes AW, Rutgers D, et al. Peripheral arterial disease in the elderly: the Rotterdam Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18:185–192.

9 Kannel WB, McGee DL. Update on some epidemiologic features of intermittent claudication: the Framingham Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1985;33:13–18.

10 Rockson SG, Cooke JP. Peripheral arterial insufficiency: mechanisms, natural history, and therapeutic options. Adv Intern Med. 1998;43:253–277.

11 Mullenix PS, Andersen CA, Starnes BW. Atherosclerosis as inflammation. Ann Vasc Surg. 2005;19:130–138.

12 Davies MJ, Richardson PD, Woolf N, et al. Risk of thrombosis in human atherosclerotic plaques: role of extracellular lipid, macrophage, and smooth muscle cell content. Br Heart J. 1993;69:377–381.

13 Rivard A, Andres V. Vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation in the pathogenesis of atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases. Histol Histopathol. 2000;15:557–571.

14 Lafont A, Topol EJ. Arterial remodelling: a critical factor in restenosis. Boston: Academic Press; 1997.

15 Abbott WM, Maloney RD, McCabe CC, et al. Arterial embolism: a 44 year perspective. Am J Surg. 1982;143:460–464.

16 Falanga V, Fine MJ, Kapoor WN. The cutaneous manifestations of cholesterol crystal embolization. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122:1194–1198.

17 Criqui MH, Fronek A, Klauber MR, et al. The sensitivity, specificity and predictive value of traditional clinical evaluation of peripheral arterial disease: results from noninvasive testing in a defined population. Circulation. 1985;71:516–522.

18 Olin JW, Kaufman JA, Bluemke DA, et al. Atherosclerotic Vascular Disease Conference: Writing Group IV: imaging. Circulation. 2004;109:2626–2633.

19 Whelan JF, Barry MH, Moir JD. Color flow Doppler ultrasonography: comparison with peripheral arteriography for the investigation of peripheral vascular disease. J Clin Ultrasound. 1992;20:369–374.

20 Bluemke DA, Chambers TP. Spiral CT angiography: an alternative to conventional angiography. Radiology. 1995;195:317–319.

21 Rubin GD, Schmidt AJ, Logan LJ, et al. Multi-detector row CT angiography of lower extremity arterial inflow and runoff: initial experience. Radiology. 2001;221:146–158.

22 Grist TM. MRA of the abdominal aorta and lower extremities. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2000;11:32–43.

23 Shinnar M, Fallon JT, Wehrli S, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of ex vivo MRI for human atherosclerotic plaque characterization. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:2756–2761.

24 Oliva VL, Denbow N, Therasse E, et al. Digital subtraction angiography of the abdominal aorta and lower extremities: carbon dioxide versus iodinated contrast material. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1999;10:723–731.

25 Yeager RA, Moneta GL, Taylor LM, Jr., et al. Surgical management of severe acute lower extremity ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 1992;15:385–391. discussion 392–3

26 Jackson MR, Clagett GP. Antithrombotic therapy in peripheral arterial occlusive disease. Chest. 119(Suppl), 2001. 283S–299S

27 Huettl EA, Soulen MC. Thrombolysis of lower extremity embolic occlusions: a study of the results of the STAR Registry. Radiology. 1995;197:141–145.

28 Kessel DO, Berridge DC, Robertson I. Infusion techniques for peripheral arterial thrombolysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1, 2004. CD000985

29 Gardner AW, Poehlman ET. Exercise rehabilitation programs for the treatment of claudication pain: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 1995;274:975–980.

30 Ouriel K. Peripheral arterial disease. Lancet. 2001;358:1257–1264.

31 Aboyans V, Criqui MH, Denenberg JO, et al. Risk factors for progression of peripheral arterial disease in large and small vessels. Circulation. 2006;113:2623–2629.

32 Brothers TE, Robison JG, Sutherland SE, et al. Racial differences in operation for peripheral vascular disease: results of a population-based study. Cardiovasc Surg. 1997;5:26–31.