Chapter 16 Perioral Reconstruction

INTRODUCTION

The lips have no underlying bony or cartilaginous attachments, leaving them quite pliable. This elasticity allows for the broad movements required for verbal and nonverbal communication.1 Perioral reconstructive goals include maintaining oral competency, oral access, and mobility while providing an excellent aesthetic outcome. Maintaining function takes highest priority.2

In this chapter a regional approach to reconstruction of lip defects, primarily partial thickness, will be presented. When planning reconstruction of the lip, designing techniques based on aesthetic subunits will enhance the cosmetic result.3 Closures will vary, depending upon location, size, shape, and depth of the defect. Reconstruction in the perioral region is often challenging and to obtain optimal results requires a profound knowledge of perioral anatomy, including cosmetic subunits, vascular supply, innervation, musculature, and surrounding tissue availability.1 Finally, general principals and regional pearls for improving cosmetic outcome will be discussed.

Cosmetic Subunits

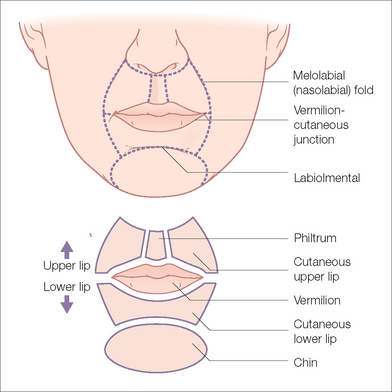

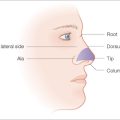

There are five cosmetic subunits delineating the perioral region into important boundaries and landmarks (Figure 16.1).4 When designing closures, these subunits should be respected, whether the closures are simple or need the use of extensive tissue movement. It is understood that in large defects or those that overlap subunits, strict adherence to this principal is not always possible.

The upper lip is divided into three cosmetic subunits, viz, the philtrum and the right and left cutaneous upper lip. The alar creases, the alar sill, and columella border the upper lip superiorly. Laterally, the borders are delineated by the melolabial folds extending inferolaterally to the oral commissures. The philtrum comprises the philtral crests or columns laterally and the sulcus medially (Figure 16.1). Great care should be undertaken to maintain the philtrum at the midline. The inferior portion of the philtrum forms Cupid’s bow (Figure 16.1). With age the philtrum becomes less prominent.

Sensory Innervation

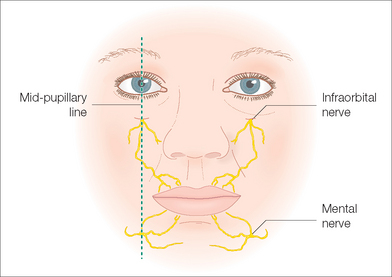

Sensory innervation to the perioral region is relatively straightforward. Innervation is supplied by branches of the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V). The infraorbital branch supplies sensation to the upper lip and the mental branch to the lower lip (Figure 16.2). Identification of the mental and infraorbital foramina aids the surgeon in providing significant anesthesia for larger lip defects. The foramina can be reached either percutaneously or via an intraoral route. Further discussion of anesthetics and regional blocks appears in the “General Principals” section.

Motor Innervation

The orbicularis oris and lip elevators receive motor inner-vation from the buccal branch of the facial (VII) nerve. The marginal mandibular branch innervates the lip depressors. Unless there is extensive muscle tissue loss, damage to these nerves is unlikely, as they lie deep to the orbicularis oris and perioral musculature. If damaged, the marginal mandibular nerve may lead to significant functional and cosmetic deformity, including the inability to pull the lower lip laterally and downward. Eversion of the vermilion may also be compromised.5

Vascular Supply

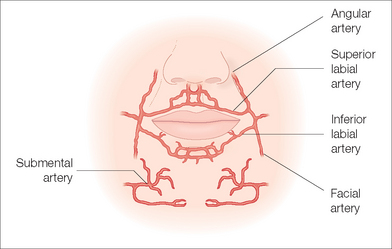

The arterial supply is derived from the superior and inferior labial arteries arising from each facial artery located just lateral to the oral commissures (Figure 16.3). The labial arteries course medially beneath the orbicularis oris muscle in the submucosa. Smaller branches of the labial arteries ascend and descend to supply the cutaneous portions of the upper and lower lips. The superior labial branches also supply the ala and columella.

GENERAL PRINCIPALS OF LIP RECONSTRUCTION

When planning reconstruction of the lips, one should pay particular attention to favorable lines of closure. Cosmetic outcome is greatly improved when incisions are placed within relaxed skin tension lines or at the borders of cosmetic subunits. The most important cosmetic unit is the vermilion– cutaneous junction. Even slight misalignment of this border during reconstruction produces disconcerting results. As previously mentioned, careful marking of the vermilion border will prevent unwanted outcomes.

Often the key to successful reconstruction is adequate undermining. Undermining of the lip occurs just above the muscle layer. When performing large advancement or transposition flaps, extensive undermining in the cheek provides adequate tissue movement and minimal tension on the wound closure. A sequela of undermining in this highly vascular region is the potential for measurable bleeding. Meticulous hemostasis is required before closing any wound on the lip. Further recommendations for improving surgical technique and cosmetic outcome are detailed in Table 16.1.

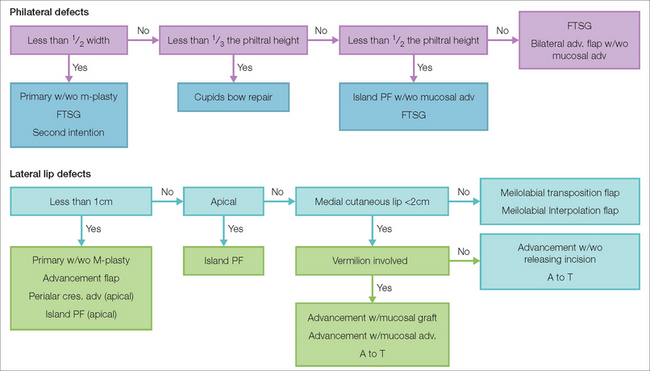

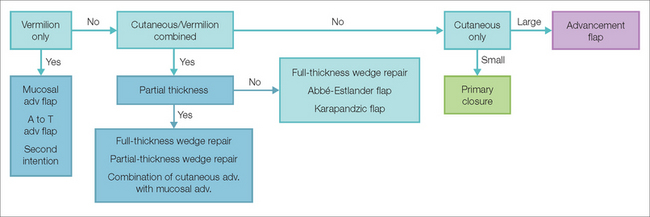

Choosing the optimal closure depends on skin laxity, as well as the size, location, and depth of the defect. Specific subunits are best served by particular closures that disguise scars in the favorable lines of that subunit. Whenever possible, reconstructive efforts should be made to close defects within a single subunit. Algorithms for reconstructive options for both upper and lower lip defects, with further division by subunit, are provided as a guideline (Figures 16.4, 16.5). These represent the variations of most common local flaps utilized in perioral reconstruction and the locations where they are best utilized. Obviously, an individualized approach to reconstruction tailored around multiple factors, including patient characteristics, is desirable in choosing the proper repair.

RECONSTRUCTION

Upper Lip Defects

Philtral Subunit

Reconstruction of the philtrum offers reconstructive surgeons a significant challenge. Creases, found on the lateral upper lip, are often absent in the philtral region. The philtrum is a reservoir of mobile skin utilized in the multitude of oral movements that stretch the upper lip, as in smiling or crying.4 The philtrum is formed by compression of dermal collagen combined with decussation of the orbicularis oris muscle fibers, which insert into the contralateral philtral ridge.4

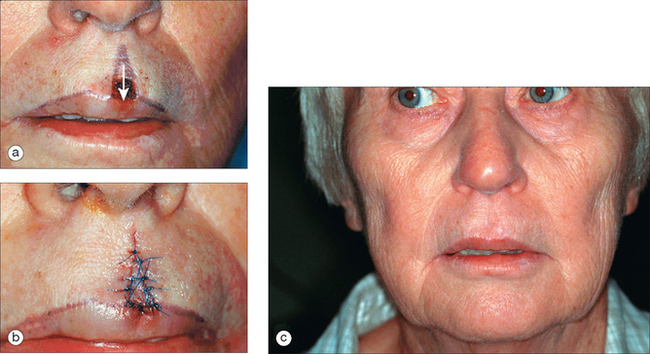

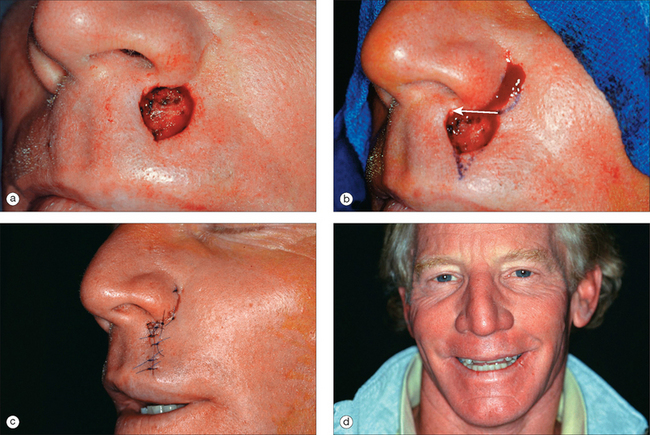

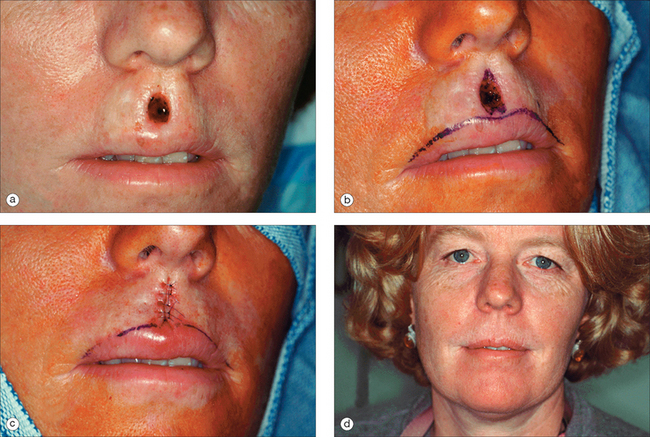

Wounds smaller than half the width of the philtrum may be closed in a side-to-side fashion with generally excellent cosmetic results (Figure 16.6). Larger wounds, closed primarily, have a tendency to risk unnatural flattening of the upper lip.6 The use of an M-plasty may be incorporated to shorten the length of the scar and prevent extending the defect onto the vermilion. It is very important to remember that because of the arc of a fusiform closure there is a lengthening of the distance between the superior and inferior ends of the defect. In larger defects closed primarily this lengthening may cause a displacement of the free margin and an unacceptable depression of the lip below the scar.6

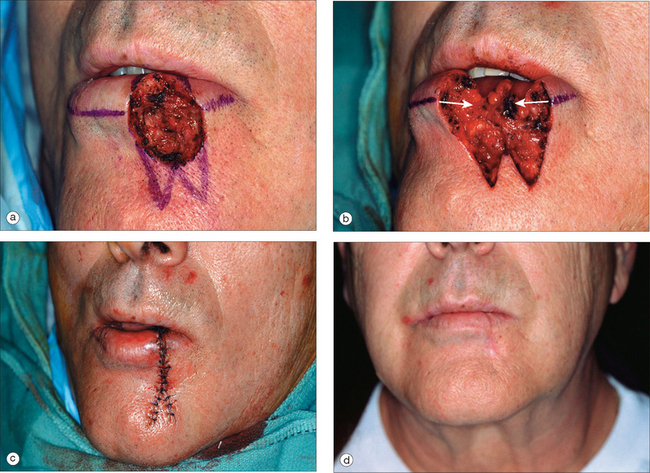

Figure 16.6 (a) Philtral sulcus defect. (b) M-plasty excised. (c) M-plasty repair sutured. (d) Long-term result.

Island pedicle flaps are ideal for defects involving the sulcus that are too large for primary closure or Cupid’s bow repairs. They are best utilized for defects encompassing less than 50% of the philtral height and up to 1.5 times the width of the philtrum.6 Defects involving greater than 50% of the philtral height have a greater chance of developing eclabium. The island pedicle flap is designed as an exaggerated equilateral triangle of tissue superior to the defect (Figure 16.7a). For large defects the triangle may extend onto the columella. The vermilion border should be marked prior to infiltration. Careful incisions are made down to the superficial subcutaneous tissue. Undermining in this plane should proceed laterally at a slight bevel away from the flap, providing a broad-based pedicle. Extensive undermining of the flap down to fascia may be necessary for adequate flap movement. A small portion of the superior and inferior attachments to the myofascia may be severed for increased movement without compromising lateral blood supply. If there is any significant tension created by the tethered pedicle of the flap, it may elevate the mucosal lip and create an unacceptable result. In some instances, it may be necessary to completely free the flap from its base and convert it into a Burow’s graft. Better to make it into a graft than to have any unnatural distortion of the vermilion. Removing normal tissue at the inferior edge of the defect down to the vermilion border may be necessary to hide the scar within the vermilion border and optimize the aesthetic result. The flap is mobilized inferiorly with the key sutures placed between the distal end of the flap and the defect (Figure 16.7b). Few, if any, subcutaneous sutures are placed as they may increase the chances of ischemia and eclabium. The secondary defect is closed easily in a side-to-side fashion. A representative final result is often imperceptible except to the trained eye (Figure 16.7c). When the vermilion lip is involved, a triangular- or rectangular-shaped mucosal advancement flap of the same width should be performed to reduce the chance of abnormally elevating the vermilion.

There are several potential disadvantages to an island pedicle flap in this location.

Although uncommon, certain large defects involving the philtrum often preclude the use of a local skin flap (Figure 16.8a). In these cases, a full-thickness skin graft (FTSG) may provide the best cosmetic outcome. It may be beneficial to remove normal tissue to make the defect more symmetrical or (Figure 16.8b) even remove the entire subunit to create a more natural appearance. The FTSG is usually harvested from the pre- or postauricular skin, as these areas can both provide enough tissue for large defects and ensure an adequate tissue match. In smaller defects, a Burow’s full-thickness graft provides a superior color and texture match.3 The FTSG is trimmed of fat and then secured with a variety of suture materials, including 5.0 or 6.0 nonabsorbable polypropylene or fast-absorbing gut (Figure 16.8c). Careful suturing technique reapproximating papillary dermis of the FTSG to papillary dermis of the wound edge improves the likelihood of achieving the best cosmetic result.7 A bolster dressing may be used to limit shearing forces on the graft during the initial phase of healing. The liberal use of petrolatum ointment in addition to petrolatum-impregnated gauze helps prevent desiccation of the graft. Sutures are left in place for 7 days.

The limitation of skin grafts in the perioral region is their tendency to pincushion and contract unevenly. This complication is seen less frequently in the concave surface of the philtrum. Their lack of color and texture match in this cosmetically sensitive area can be quite obvious. In addition, in male patients, it is extremely difficult to attain a good match for facial hair. Deep defects of the philtrum do not heal well with FTSGs and have an increased risk for eclabium.6 Burow’s grafts minimize these complications. Their advantage is the ability to minimize functional and cosmetic distortion of the lip.

Complex wounds that involve multiple subunits on the central cutaneous lip and vermilion (Cupid’s bow) can be repaired by a simple modification of the mucosal advancement flap.8 This technique is ideal for defects that encompass a small vertical diameter (less than one-third of the philtral length) and are located near Cupid’s bow (less than one-third of the distance from midline to the oral commissures) (Figure 16.9a). The technique requires the redrawing of an accurate bow around the defect. Outlining the philtral crests and central sulcus helps orient the bow correctly. The convexity of the bow is oriented superiorly with the superior most aspect in line with the philtral crests. The concavity is located in the midline of the sulcus, pointing toward the tubercle (Figure 16.9b). The incision lines extend superiorly to the exact height of the defect on the opposite side. Incision lines need to extend far enough laterally to permit a proper 30° closure to prevent standing cones (Figure 16.9c). The wedges are excised and superficial undermining above the orbicularis oris muscle is performed. The superior aspect of the flap should be undermined more extensively than the vermilion. The key suture should be placed aligning the central concavity of the cutaneous lip to the concavity of the vermilion (Figure 16.9c). The wound is then closed in one layer using soft surgical material to minimize discomfort (Figure 16.9d).

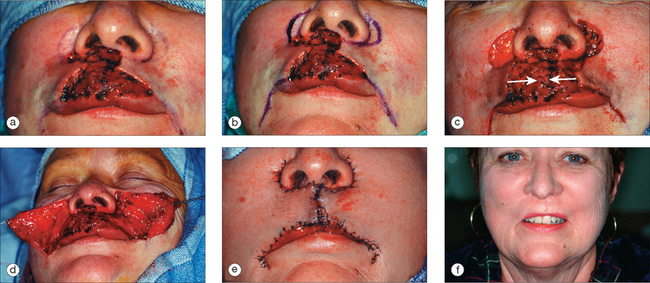

Double advancement flaps can be utilized for larger defects of the central upper lip and adjacent lateral upper lip (Figure 16.10a). If vermilion is also involved, it will be necessary to perform a mucosal advancement. Depending upon the size of the defect the lateral vermilion incisions extend laterally and inferiorly below the oral commissure (Figure 16.10b). Perialar crescents are often utilized to prevent distortion of the ala and downward push of the flap tissue, which could displace the lip, and to better camouflage the scar (Figures 16.10b, 16.10c). Wide undermining proceeds above the orbicularis muscle and extensively into the subcutaneous tissue of the cheeks (Figure 16.10d). Meticulous hemostasis is utilized to prevent postoperative complications. The use of periosteal sutures helps recreate the melolabial crease. The wound is then closed using a combination of absorbable sutures for subcutaneous– dermal approximation, nonabsorbable polypropylene sutures for cutaneous skin approximation, and nonabsorbable polybraided sutures for vermilion–cutaneous approximation (Figure 16.10e). The final result can be quite acceptable with concealment of scars within the vermilion and alar crease and below the nose (Figure 16.10f).

Lateral Subunits

Fusiform closures should be oriented vertically along relaxed skin tension lines to maximize the natural creases and help camouflage the scar. The melolabial crease should not be crossed as this tends to make the closure more obvious and creates an unnatural break in the normal arc of the crease. It may also be more apt to create an aesthetically unacceptable depression. Since scars contract along their long axis and tend to shorten slightly, anytime a closure goes across a convex surface, such as the melolabial fold, there is a significant risk of creating a depressed sunken in scar line across the contour. If the superior aspect of the fusiform is likely to violate the melolabial crease, it is best to hide the scar line close to or in the alar crease. If the defect involves the melolabial crease and it must be involved in the closure, it is often best to use an S-plasty closure to slightly redistribute the vectors of tension during healing.

To perform a simple fusiform closure, Burow’s triangles are marked both inferiorly and superiorly with the optimum angle of 30° at the apices. It is unwise to compromise the apical angles to fit a closure within the subunit. As previously mentioned the final length of the resultant closure will be extended to equal the arcs of the fusiform, so great care is needed not to distort the vermilion border. If this is likely, variations such as an M-plasty, Z plasty, or extension onto the vermilion should be considered (Figure 16.11a). The vermilion is not an inviolable structure.1 If the closure extends onto the vermilion it is often best to extend the closure onto the wet mucosa, thereby hiding the inferior portion of the scar on the inside of the lip (Figure 16.11b). Undermining is performed just above the orbicularis oris and should be carried laterally until minimal tension is noted. This often depends upon the size of the defect. If muscle has been removed during extirpation, a plication suture to reapproximate the muscle fibers is recommended, helping to decrease tension on the wound. The closure is then sutured in a layered fashion with attention applied toward wound edge eversion (Figure 16.11b). The use of vertical mattress sutures will decrease the likelihood of an atrophic dell-like scar (Figures 16.11b, 16.11c).

Figure 16.11 (a) Lateral upper lip defect with inferior Burow’s triangle drawn. (b) Primary closure sutured. (c) Long-term result.

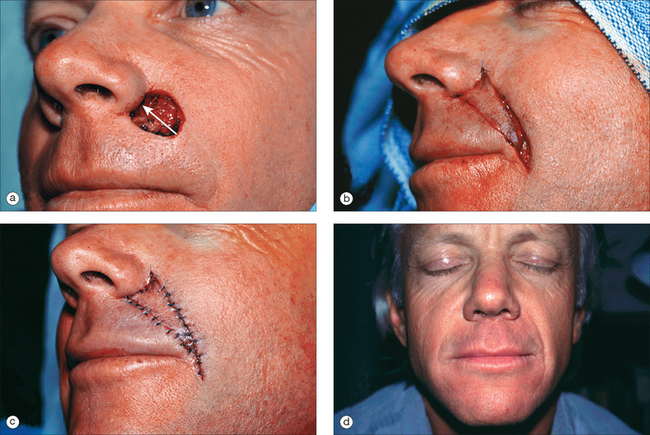

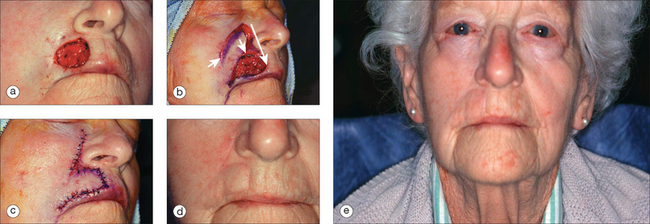

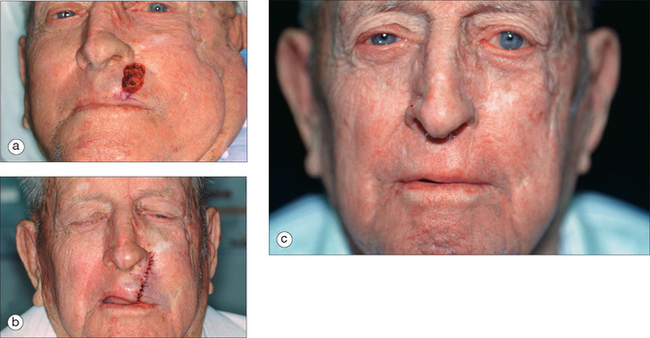

Perialar crescentic advancement flaps are perfect for small defects less than 1 cm2 that are adjacent to the inferior alar crease or below the lateral nostril sill (Figure 16.12a).9 This closure allows the surgeon the opportunity to conceal the superior suture line (crescent) within the alar crease and below the nostril while taking advantage of the abundant laxity of the cheek. The inferior scar is hidden in the RSTLs of the cutaneous upper lip. The crescent of skin is essentially a Burow’s triangle that facilitates tissue movement without inducing puckering of the skin. The crescent can be pre-excised or excised after closing the lip portion (essentially the standing cone) of the advancement flap. This will allow the crescent to define itself and may minimize tissue removal.9 In this example, the defect is inferior to the nostril sill extending laterally to the inferior ala (Figure 16.12a). The crescent and standing cone repair are drawn; making sure that the standing cone will be concealed in the RSTLs of the upper lip (Figure 16.12b). The crescent and standing cone are excised with subsequent undermining laterally in the subcutaneous tissue of the cheek and the subcutaneous–orbicularis oris junction on the lip. The movement of the flap proceeds medially with the key suture placed where the inferior portion of the crescent meets the superior aspect of the defect (Figure 16.12c). In larger defects it may be necessary to recruit tissue medial to the defect as well. The suture line is well camouflaged below the nose (Figure 16.12c). Excellent cosmetic outcomes are routine with the perialar crescent (Figure 16.12d).

The advantages to the perialar crescent include utilization of closely matched tissue of the perialar cheek without obliteration of the melolabial fold. The scars are well concealed along the alar–facial sulcus. Larger defects in this location are best repaired by an island pedicle flap, larger advancement flap, crescent designed within the melolabial crease, or interpolation flap.9 Limitations to the perialar flap are large defects that may preclude closure of the standing cone within the cutaneous upper lip or wounds that are more medially placed. An A-to-T advancement flap is often the choice for medial defects lying just below the nostril sill. Of course patient variation in laxity and size of the upper lip cosmetic unit will dictate the closure option.

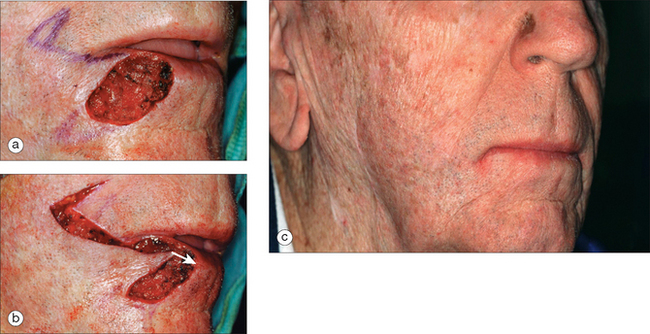

Island pedicle flaps are ideally suited for large defects involving the lateral aspect of the upper lip that are adjacent to or lying within the melolabial crease and abutting the nasal ala (Figure 16.13a). The facial artery parallels the melolabial crease prior to its connection with the angular artery. This provides a generous blood supply via numerous perforators to the island pedicle flap. The melolabial crease can often be incorporated into the triangular incision to camouflage the superior aspect of the flap (Figure 16.13b). The skin island is designed with its leading edge formed by the inferolateral margin of the defect most nearest to the melolabial crease. The axis is designed to parallel the melolabial crease, ensuring retention of the crease after closure. The width of the skin paddle should equal the diameter of the defect at its widest point.10 The ideal length of the paddle should ordinarily be twice the defect size along the axis of flap advancement.10 The tail of the flap should be gently tapered for ease of closure with minimal lateral or upward pull on the oral commissure. For larger defects the flap may extend as far down as the mandible. The flap is excised to superficial subcutaneous tissue with undermining within this plane beveling outward for up to 2 cm. This may extend down to fascia if needed. Deeper undermining at the level of the fascia along the edges of the flap may be necessary to improve mobility. The pedicle may be thinned at its superior and inferior edges for maximum mobility as well as to best match the depth of the defect. The rich blood supply allows for a pedicle significantly smaller than is needed in the philtral region. Further lateral undermining can facilitate wound eversion and decrease the chances of a trapdoor effect. It is always wise to check mobility multiple times with a skin hook to ensure adequate flap movement. The leading edge of the flap and the defect may be squared off to minimize pin-cushioning.1 The key sutures are placed in the leading edge of the flap using 5.0 polypropylene or similar nonabsorbable suture (Figure 16.13b). Absorbable subcutaneous sutures are helpful in providing wound eversion. After the key sutures are placed, the remaining flap perimeter is closed with alternating sutures to ensure equitable tension and minimize distortion (Figure 16.13c). The secondary defect is easily closed. The island pedicle flap is an excellent choice for large defects of the apical lip (Figure 16.13d).

The advancement flap should be designed so that the inferior horizontal scar is hidden along the vermilion border (Figure 16.14a) and great care should be made to delineate this prior to infiltration of anesthetic. The advancement flap should be designed ideally with a 3:1 length-to-width ratio, although in the perioral region shorter lengths are often used with good results. The incision proceeds along the vermilion border laterally. Extensive undermining, within the skin superior to the orbicularis muscle on the cutaneous lip, and in the subcutaneous tissue of the cheek, is performed. This provides adequate flap movement with minimal wound tension or displacement of the philtrum. Undermining of the vermilion is minimal. The Burow’s triangle is removed superiorly with the vertical scar parallel to or within RSTLs. The Burow’s triangle may be removed prior to or after the flap is advanced. The exact amount of the Burow’s triangle to be removed is best appreciated after flap advancement. The key suture is placed at the inferior edge of the flap and defect near the vermilion. This allows for proper alignment of the cutaneous–vermilion border. Wound closure proceeds with absorbable sutures to approximate the subcutaneous tissue and dermis of the cutaneous lip (Figure 16.14b). Nonabsorbable polypropylene is used for skin edge approximation utilizing vertical mattress suturing technique for maximal eversion. The vermilion– cutaneous border is closed with nonabsorbable polybraided sutures by a halving technique. It is important to place five or six throws to ensure knot security.

In cases of large defects of the upper lip (Figure 16.15a), where considerable horizontal advancement is needed, extension of the lateral incision should be extended inferolaterally below the oral commissure. Incising below the commissure decreases the chances of hooding in this region. More extensive undermining of the adjacent cheek superiorly and laterally will allow enough tissue movement to cover the defect. A Burow’s triangle may be removed for additional tissue movement (Figure 16.15b). Removal of a perialar crescent assists in superior tissue movement with concealment of the suture lines in the alar crease (Figure 16.15b). The closure should proceed in the same order as in a less complicated advancement flap (Figure 16.15c). Partial-thickness wedge resection has been recommended for defects that extend into the orbicularis oris muscle and mucosa, when the muscular defect is smaller than the cutaneous defect.11 The thought is to wedge out a proper amount of muscle tissue to create straight wound edges of muscle. The muscle is then approximated using an absorbable plication suture. The remaining cutaneous defect is then closed with an advancement flap.11 The final result shows slight hooding of the lateral lip and oral commissure, as well as slight distortion of the vermilion border (Figure 16.16a). To improve the lateral hooding, a small amount of redundant tissue was excised (Figure 16.16b). To resolve the distortion of the vermilion border a Z-plasty was designed at the superior portion of the cutaneous scar. By placing it superiorly instead of at the vermilion the scars were better concealed and further distortion was prevented (Figures 16.16b, 16.16c). The final result shows both improvement of the hooding and distortion of the vermilion border with a well-camouflaged scar beneath the nostril sill (Figure 16.16d).

In cases where cutaneous defects are accompanied by loss of the mucosal lip, a combination of an advancement and mucosal graft is an excellent option for repair. The defect encompasses the inferior and lateral portion of the cutaneous upper lip and a significant portion of the lateral vermilion (Figure 16.17a). The advancement flap is designed laterally in typical fashion. The vermilion is reapproximated and the cutaneous defect closed prior to suturing the mucosal graft (Figure 16.17b). The graft is taken in a horizontal or vertical direction from the wet mucosa of the lower lip (Figure 16.17c). Grafts in the vertical direction are preferred for ease of closure and because of fewer postsurgical complications. The use of soft suturing material (ie, Ticron or Ethibond) is used to secure the graft (Figure 16.17d). Mucosal grafts have a low failure rate and provide excellent tissue match (Figure 16.17e). The graft should remain secured for 10–14 days to avoid disruption of the graft–bed contact. The patient is educated to avoid traumatizing the graft by minimizing overexaggerated lip movements and instructed to eat softer foods until the sutures are removed.

Superficial defects greater than 2 cm on the lateral upper lip may be closed with an inferiorly or superiorly based melolabial transposition flap (Figure 16.18). In some instances the entire subunit is removed for an improved cosmetic result. The flap is planned with the donor site closure within the melolabial fold. The flap is designed 1–2 mm wider than the defect to prevent retraction of the lip. Careful measurement of the flap is paramount to ensure enough length to cover the defect. An infraorbital nerve block will help achieve adequate anesthesia. Once the flap is designed and excised, the normal tissue to be discarded is not removed until the transposition flap has been elevated and judged to be of adequate size. The flap and cheek are undermined below the subdermal plexus. The key suture is placed to close the donor site, thereby relieving tension on the flap. Placing a deep nonabsorbable suture into the periosteum of the piriform aperture can approximate the donor site. The flap is then transposed and trimmed to match the defect. The defect should be trimmed to square the edges (Figure 16.18b). The flap is then closed with absorbable subcutaneous and nonabsorbable cutaneous sutures (Figure 16.18c).

The traditional rhombic transposition flap is rarely employed in perioral closures. Pin-cushioning and blunting of the melolabial crease are complications of transposition flaps in this region (Figure 16.18d). Thinning of the flap and wide undermining decrease the risk of pin-cushioning, and periosteal sutures may help restore the melolabial crease. Often, multiple intralesional steroid injections or surgical revisions are needed to realize acceptable cosmetic results (Figure 16.18e). Bilateral transposition flaps may on occasion be used to close defects of the philtral subunit. They are designed to have the long axis of the secondary defect closed along the philtral columns.

Full-thickness defects of the upper lip can be closed by a variety of local flaps, depending upon size and location of the defect. Full-thickness defects less than one-third of the vermilion length can be closed using a multilayer primary V-shaped closure. A four-layer closure can provide a superior surgical scar over the traditional three-layered repair.12 Particular care is taken to assure that mucosal and muscle tissue are reapproximated separately with nonabsorbable sutures, followed by dermis and then wound edge. The cornerstone of an optimal surgical result is correct approximation of the vermilion border.

Larger full-thickness defects require tissue movement more extensive than can be provided by simple wedge repair. The Abbé–Estlander flap is a full-thickness lip-switch flap consisting of a pedicle based on the labial artery of the opposite lip. The flap has the advantage of rotating tissue of appropriate thickness and supplying the exact skin color and mucous membranes. The flap pedicle is transected in 2–3 weeks. (See Figures 8.23Figure 8.24Figure 8.25Figure 8.26Figure 8.27Figure 8.28Figure 8.29–Figure 8.30 of Chapter 8.) Disadvantages of the flap are that it provides denervated tissue and distortion of the oral commissure, requiring subsequent commissure repair.

The Karapandzic flap is frequently used in larger full-thickness defects. It has the added advantage of retaining its neurovascular integrity, providing better function for the oral aperature.13 The disadvantage is varying degrees of microstomia and distortion of the oral commissure. Over time the microstomia should improve.

Lower Lip Defects

Mucosal Lip/Vermilion Subunit

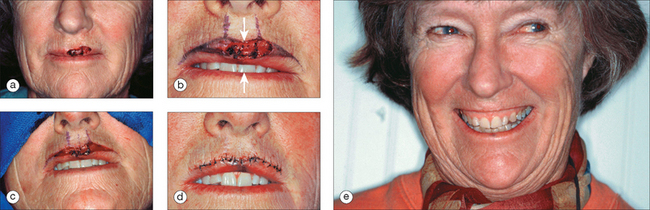

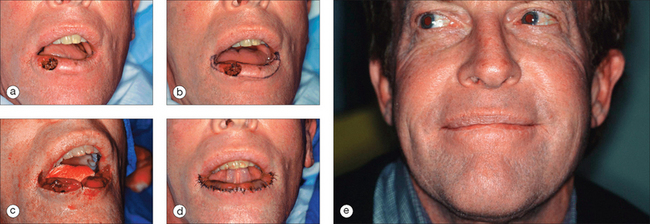

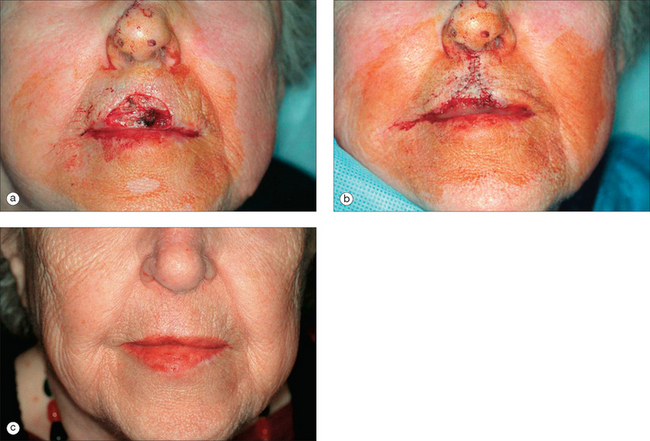

Squamous cell carcinomas are the most common tumor of the vermilion whereas basal cell carcinomas most often affect the cutaneous lower lip. Actinic damage, smoking, and smokeless tobacco products are etiologic factors leading to squamous cell carcinomas of the lower lip. Often, patients with squamous cell carcinomas of the vermilion will have little or no involvement of the cutaneous portion of the lower lip. The remaining vermilion may consist of actinically damaged skin. A partial mucosal advancement or an A-to-T closure hidden in the vermilion border can be used for small defects confined to the vermilion where there is minimal adjacent actinic cheilitis. Second intention healing for small shallow defects should be considered and often lead to excellent results without distortion of the vermilion border. For larger defects, with adjacent actinically damaged tissue, a complete vermilionectomy will need to be performed (Figure 16.19).

To ensure proper alignment, the mucosal advancement flap should be designed and marked out along with the vermilion border prior to anesthetic infiltration. It is often very difficult to accurately discern precise tissue movement and its effects on surrounding tissue once the area has been infiltrated with anesthesia. In addition, anesthesia often distorts the rolled border and dry–wet line. The marking of the vermilion border should extend past the oral commissures, ending approximately 0.5 to 1.0 cm above the commissures on the lateral aspect of the upper lip vermilion (Figure 16.19b). The posterior incision line should be drawn extending from the most posterior aspect of the defect laterally to meet the anterior incision line at the upper lip vermilion. This reduces the possibility of a trough developing at the angles of the mouth. The first incision extends laterally from either side of the defect along the vermilion border; thereafter the posterior line may be incised. The tissue is removed with care so as to avoid excision of the underlying orbicularis oris muscle. Trauma to the muscle increases bleeding and increases the possibility for hematoma formation. The wet mucosa is dissected in the submucosal plane preferably below the minor salivary glands and above the musculature.14 Dissection above the glands increases the chance of flap ischemia. Undermining should proceed in this plane down to the sulcus, if need be. For smaller or narrower defects this degree of undermining may not be necessary. A skin hook can be used to move the tissue forward, assuring adequate movement. Care should be taken as the mucosa is easily traumatized. Dissection should be continued until the defect is repaired with minimal tension. Again, soft braided nonabsorbable sutures are used to secure the advancement flap with the key stitch placed in the middle of the flap at the point of greatest tension (Figure 16.19c). Employing the halving technique on either side of the key suture helps reduce tension and puckering of the closure (Figure 16.19d).

There are several advantages to the mucosal advancement flap. With proper surgical technique the chance of ischemia is minimal. The rich blood supply allows the flap to heal relatively quickly. Scars are concealed along the vermilion border (Figure 16.19e). Extending the surgical defect above the oral commissure onto the lateral upper lip camouflages the terminal ends of the scar and decreases the risk of trough development.

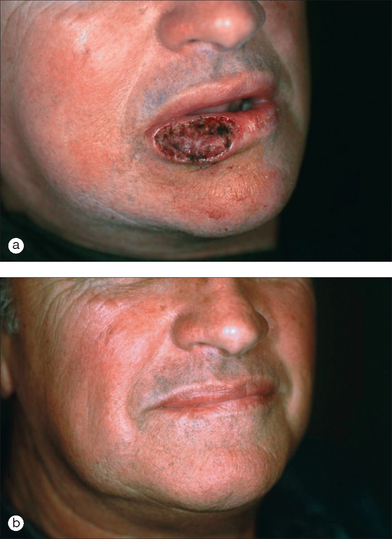

Some partial-thickness wounds of the mucosal lip heal quite well with second intention. Although there is a risk for contraction, resulting in distortion of the lip, quite often no such distortion occurs and the mucosal lip has a unique ability to regenerate itself completely and be aesthetically very pleasing (Figures 16.20a and 16.20b).

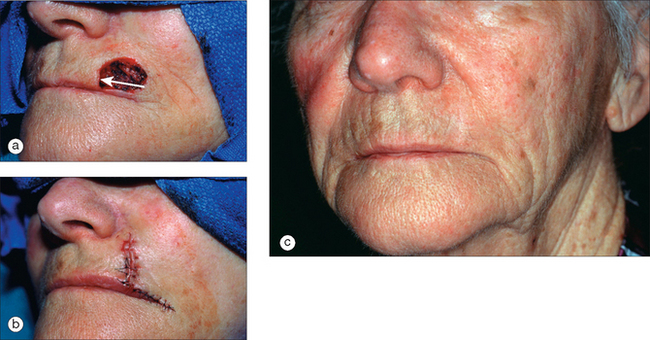

Cutaneous Lower Lip Subunit

When possible, one should incorporate the labiomental crease or vermilion border when performing advancement flaps. Larger defects of the lateral lower lip can be closed with advancements that extend and utilize the melolabial crease (Figure 16.21a). The lateral incision is made along the vermilion border extending onto the melolabial crease (Figure 16.21b). A Burow’s triangle may be removed superiorly in the crease. The standing cone is aligned within the natural skin tension lines. Both the Burow’s triangle and standing cone are well concealed postsurgically (Figure 16.21c).

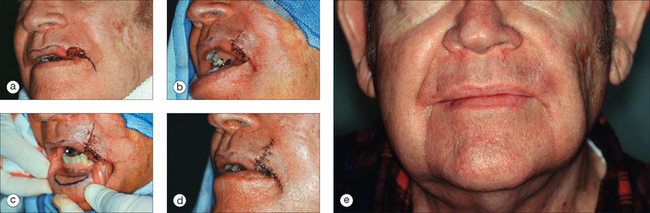

Full-Thickness Defects

A full-thickness wedge repair is ideal for deep or full-thickness defects that involve both the vermilion and cutaneous lower lip. Traditionally limited to wounds up to one-third of the lower lip, there are many who advocate its use for defects involving up to 50% of the lower lip.15 Obviously, patient selection is important when deciding whether a wedge repair will achieve the desired result. Factors include previous surgery, skin laxity, retaining lip function, and cosmetic results. The wedge, or V-shaped repair, has been the standard method of reconstruction for deep or full-thickness defects (Figure 16.22a). For aesthetics, the closure should be designed in concert with the relaxed skin lines. An M-plasty can be used inferiorly to avoid the labiomental crease (Figure 16.22b). An intraoral mental nerve block prior to reconstruction greatly decreases patient pain and minimizes anesthetic distortion of the lip. Isolating and ligating the labial arteries can simplify removal of the wedge and subsequent reconstruction. Specific attention should be given to reapproximation of the intramucosa, orbicularis muscle, subcutaneous tissue, and skin surface. When closing the deeper structures it is necessary to monitor the approximation of the vermilion border, making sure it is not distorted. Accurate reapproximation of the muscle includes the superior aspect that lies just below the vermilion, thereby decreasing the chance of notching. Polybraided nonabsorbable sutures are utilized in closure of the intraoral mucosa and vermilion. Absorbable sutures (ie, Vicryl, PDS) are used to reapproximate the orbicularis muscle and subcutaneous tissue. Nonabsorbable polypropylene sutures may be used for purely cutaneous closure. Vertical mattress sutures employed in vermilion reapproximation will minimize the development of a trough-like scar.

Postoperative Principals

Since scars tend to do worse with tension and motion, small injections of botulinum toxin in the perioral area following surgery may reduce the motion on the scar as it is healing and potentially result in a thinner scar line. Approximately one unit of botulinum toxin may be injected at the vermilion border into the four quadrants of the upper lip and along three points of the lower lip (Figure 16.23). Patients should be warned that there could be a slight change in the way they pronounce certain sounds for several weeks following the injection. Caution should obviously be taken not to inject too much toxin in the area or more significant changes may occur.

1 Lask GP, Moy RL. Part IV Chemical destructive techniques: lip reconstruction. Principals and techniques of cutaneous surgery. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1996;329-339.

2 Larrabee WFJr, Sherris DA. Lips and chin: principals of facial reconstruction. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1995;170.

3 Zitelli JA, Brodland DG. A regional approach to reconstruction of the lip. J Dermatol Surg Onco. 1991;17:143.

4 Salasche SJ, Bernstein G, Senkarik M. Regional anatomy III: The lip. Surgical anatomy of the skin. Norwalk, CT: Appleton and Lange, 1988;224-225.

5 Salasche SJ, Bernstein G, Senkarik M. Classic systems of anatomy II: The facial nerve. Surgical anatomy of the skin. Norwalk, CT: Appleton & Lange, 1988;108.

6 Kaufman AJ, Grekin RC. Repair of central upper lip (philtral) surgical defects with island pedicle flaps. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22:1003-1007.

7 Zitelli JA. Burow’s grafts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:271-279.

8 Paniker PU, Mellette JR. A simple technique for repair of Cupid’s bow. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:636-640.

9 Mellette JR, Harrington AL. Applications of the crescentic advancement flap. J Dermatol Surg Onco. 1991;17:447-454.

10 Rustad TJ, Hartshorn DO, Clevens RA, Johnson TM, Baker SR. The subcutaneous pedicle flap in melolabial reconstruction. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;124:1163-1166.

11 Spinowitz AL, Stegman SJ. Partial thickness wedge and advancement flap for upper lip repair. J Dermatol Surg Onco. 1991;17:581-586.

12 Godek CP, Weinzweig J, Bartlett SP. Lip reconstruction following Mohs’ surgery: the role for composite resection and primary closure. Plast Recons Surg. 2000;106:798-804.

13 Goslen JB, Thomas JR. Cancer of the perioral region. Dermatol Clin. 1989;7:733-749.

14 Cook JL. Reconstruction of the lower lip. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:775-778.

15 Baker SR, Swanson NA. Local flaps in facial reconstruction: reconstruction of the lip. St Louis, MO: Mosby, 1995;361.