Perioperative pulmonary aspiration

Importance of pulmonary aspiration

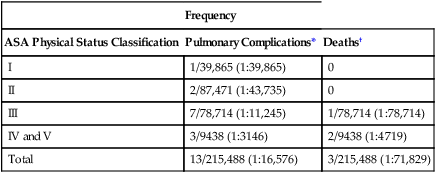

Five large studies from 1970 to 2000 documented the overall frequency of perioperative pulmonary aspiration to be approximately 1:3000; the mortality rate is 5% in patients who have a witnessed aspiration. Fortunately, not all patients who aspirate develop respiratory sequelae. The frequency of pulmonary complications and fatality as a consequence of aspiration are shown in Table 241-1.

Table 241-1

Risk of Aspiration-Associated Pulmonary Complications and Death after General Anesthesia by American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification

| Frequency | ||

| ASA Physical Status Classification | Pulmonary Complications* | Deaths† |

| I | 1/39,865 (1:39,865) | 0 |

| II | 2/87,471 (1:43,735) | 0 |

| III | 7/78,714 (1:11,245) | 1/78,714 (1:78,714) |

| IV and V | 3/9438 (1:3146) | 2/9438 (1:4719) |

| Total | 13/215,488 (1:16,576) | 3/215,488 (1:71,829) |

ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists.

*Pulmonary complications include acute respiratory distress syndrome, pneumonitis, and pneumonia (with or without positive viral or bacterial identification).

†Death from aspiration-associated pulmonary complications within 6 months of aspiration.

From Warner MA, Warner ME, Weber JG. Clinical significance of pulmonary aspiration during the perioperative period. Anesthesiology. 1993;78:56-62.

Based on the information in Table 241-1, if similar mortality rates were to be found within the United States in general, approximately 200 deaths from perioperative pulmonary aspiration would be expected each year. In our largest institutions (i.e., those that perform as many as 50,000 general anesthetics annually), only 1 death from pulmonary aspiration would occur every 18 months. By applying the numbers (1 death per 75,000 general anesthetics) to individual practice settings, an idea of the anticipated frequency of this event can be derived.

Use of medications and preoperative fasting

Medications used to decrease gastric contents, acidity, or both clearly work. However, no data suggest that the use of these medications decreases the risk of pulmonary aspiration. Many anesthesia organizations have developed guidelines to decrease the risk of perioperative aspiration, and all guidelines make similar recommendations. The recommendations of the American Society of Anesthesiologists for medications and fasting are given in Tables 241-2 and 241-3, respectively. Routine use of these medications is NOT recommended, and yet many anesthesia providers feel compelled to administer these medications to their patients, despite an adverse risk-benefit ratio. Evidence is lacking, but the only patients who might benefit are those in whom the anticipated risk of pulmonary aspiration is high.

Table 241-2

Summary of 1999 American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force Pharmacologic Recommendations to Reduce the Risk of Pulmonary Aspiration*

| Drug Type and Common Examples | Recommendation |

| Gastrointestinal stimulants | |

| Metoclopramide | No routine use |

| Gastric acid secretion blockers | |

| Cimetidine | No routine use |

| Famotidine | No routine use |

| Lansoprazole | No routine use |

| Omeprazole | No routine use |

| Ranitidine | No routine use |

| Antacids | |

| Sodium citrate | No routine use |

| Sodium bicarbonate | No routine use |

| Magnesium trisilicate | No routine use |

| Antiemetic agents | |

| Droperidol | No routine use |

| Ondansetron | No routine use |

| Anticholinergic agents | |

| Atropine | No use |

| Scopolamine | No use |

| Glycopyrrolate | No use |

| Combinations of the medications above | No routine use |

ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists.

*A 2011 update of these guidelines states that, in patients who have no apparent risk of pulmonary aspiration, the routine preoperative use of gastrointestinal stimulants, antacids, gastric acid blockers, antiemetics, anticholinergics, or combinations thereof is not recommended.

Table 241-3

Summary of 2011 Updated American Society of Anesthesiologists Committee on Standards and Practice Parameters’ Recommendations on Preoperative Fasting and the Use of Pharmacologic Agents to Reduce the Risk of Pulmonary Aspiration*

| Ingested Material | Minimum Fasting Period (h)† |

| Clear liquids‡ | 2 |

| Breast milk | 4 |

| Infant formula | 6 |

| Nonhuman milk§ | 6 |

| Light meal¶ | 6 |

*These recommendations apply to healthy patients who are undergoing elective procedures. They are not intended for women in labor. Following the guidelines does not guarantee complete gastric emptying.

†The recommended fasting periods apply to all ages.

‡Examples of clear liquids are water, fruit juices without pulp, carbonated beverages, clear tea, and black coffee.

§Because nonhuman milk is similar to solids in gastric emptying time, the amount ingested must be considered in determining an appropriate fasting period.

¶A light meal typically consists of toast and clear liquids. Meals that include fried or fatty foods or meat may prolong gastric emptying time. Both the amount and type of foods ingested must be considered when determining an appropriate fasting period.