CHAPTER 19 Perioperative Management of Patients with Meningiomas

PREVENTION OF SEIZURES IN MENINGIOMA PATIENTS

Seizures are among the most common presenting symptoms in meningiomas. Various authors have reported seizures as the presenting symptom in 20% to 50% of meningiomas.1–7 This incidence is slightly higher if only supratentorial meningiomas are considered (29%–67%).5,8,9 This rate is similar to the incidence of 30% to 50% reported for brain tumors in general.10 Among all meningiomas, convexity, anterior third parasagittal, and sphenoid wing meningiomas have the highest incidence of seizures.1,4 Although the incidence of meningiomas is more common in women, several studies have shown that seizures are equally common in female and male meningioma patients.1,4,9 Similarly, the incidence of a presentation with seizures is equally common in all age groups.4 There is also no reported significant association of seizures with any histological type of meningioma.1,4,11 The presence of peritumoral edema has a highly significant correlation with seizures in patients with meningiomas.4,11 The high concentration of glutamate and aspartate has been suggested as the cause for this increased risk of seizures.12,13

Meningioma patients who have presented with seizures are routinely treated with antiepileptics. Despite such treatment, brain tumor patients who have presented with seizures have an increased risk of recurrent seizures.14 Surgical resection of meningiomas is reported to eliminate seizures in 19.2% to 63.5% of patients who had presented with epilepsy.5,8,9 However, one third of patients with preoperative seizures are reported to have postoperative epilepsy. Therefore, preoperative epilepsy is a significant risk factor for postoperative epilepsy.

Initiation of antiepileptic treatment in meningiomas is justified after presentation with seizures. However, as with most other brain tumors, the indication of antiepileptic prophylaxis in patients who have never had a seizure remains controversial. In general, 20% to 45% of patients with brain tumors who have never had a seizure will develop epilepsy during the course of the disease.14 Therefore, prophylactic treatment sounds logical. However, the efficiency of antiepileptic medications in preventing seizures in brain tumor patients is debated and all of the antiepileptics are associated with a broad range of side effects, some of which can be quite severe or even life threatening. In two randomized studies, the use of phenytoin was found ineffective in patients with supratentorial tumors.15,16 The Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology published a consensus statement in 2000, recommending not to use antiepileptic drugs in patients with brain tumors routinely and to withdraw the drugs in the first week after surgery if the patients have never had a seizure.14 A more recent meta-analysis by Sirven and colleagues17 separately analyzed the seizure outcome in different brain tumor subtypes and similarly concluded that antiepileptic treatment was ineffective in patients with gliomas, metastases, or meningiomas who never had a seizure.17 However, this study did not have enough statistical power to be conclusive. A recent Cochrane Library review analyzed five clinical trials with random allocation of seizure-free brain tumor patients to phenobarbital, phenytoin, and valproate and concluded that there was no statistical difference between treatment, placebo, or observation.18 However, this systematic review also pointed out that the only study, which had statistical power, suffered from several biases that weakened its conclusions. The Cochrane Library review stated that the evidence available at present is neither in favor nor against seizure prophylaxis in patients with brain tumors.18

Seizures after surgical treatment of meningiomas may be related to the meningioma itself or to craniotomy. Development of new-onset postoperative epilepsy is reported in 5.1% to 42.9% of meningioma patients who did not have seizures preoperatively.1–5,8,9 Approximately two thirds of these new-onset seizures are seen in the first 48 hours after surgery.4,19 Such an early presentation of seizures is associated with a high likelihood of becoming seizure-free with antiepileptic medications. Lieu and colleagues4 have reported that 71.2% of patients are reported to become seizure-free after a year of antiepileptic treatment. Postoperative epilepsy is more common in patients who had iatrogenic injury to cortical veins or arteries or in cases where significant brain retraction was required during surgery. Patients who had preoperative epilepsy or those who had postoperative hydrocephalus are more commonly associated with postoperative epilepsy.1,5,8,9,20 An association with subtotal resection is controversial.4 Similarly the association of parietal localization with an increased risk of postoperative epilepsy was reported by Chozick amd colleagues9 but not reconfirmed by others.4 It should be kept in mind that postoperative seizures can be secondary to meningitis or promoted by infections in other sites such as the urinary system. Laboratory investigations are prompted in the case of a postoperative seizure.

There is very scant information on the choice of antiepileptic drugs in brain tumor patients with epilepsy. Owing to lack of evidence, recommendations for the general epileptic population are extrapolated to treatment of brain tumor patients. Carbamazepine and lamotrigine are first-line treatment recommendations for symptomatic localization-related epilepsy.21 Although carbamazepine is one of the most effective drugs for the treatment of partial epilepsy, Wick and colleagues,22 in their study on gliomas, showed that recurrent seizures were observed in 70% of those who were treated with carbamazepine, in 51% of those who were given phenytoin, and in 44% who received valproic acid. Newer antiepileptics are commonly used as add-on drugs in the case of persistent seizures despite medical treatment. Levetiracetam and gabapentin are reported to be effective and well tolerated as add-on drugs in patients with persistent seizures.23–25 Patients who have seizures refractory to medical treatment may be candidates for epilepsy surgery. Surgical resection of an epileptic focus related to a brain tumor has been proven to be very effective treatment modality. Seventy to ninety percent of patients are reported to become seizure free or have substantial decline in seizure frequency.10,26

Most antiepileptic medications have significant side effects, and this is the major drawback of antiepileptic prophylaxis that should be weighed against its gains. Major clinical trials on antiepileptic treatment in brain tumor patients were conducted using phenytoin, phenobarbital, and valproate. These studies reported nausea, dermatological reactions ranging from mild rashes to severe systemic complications such as Stevens Johnson syndrome, sore gums, bone marrow suppression, vertigo, blurred vision, tremor, and gait unsteadiness among adverse events. The incidence of side effects is higher in the population with brain tumors when compared to the general population with epilepsy.10,26 Drug interactions among antiepileptic drugs and with other drugs used in the treatment of patients with meningiomas are also commonly observed. Phenytoin increases the hepatic metabolism of steroids, decreasing their activity but inversely the blood level of phenytoin may also be influenced during steroid use due to competition for protein binding and interference with hepatic metabolism.

MANAGEMENT OF PERITUMORAL BRAIN EDEMA

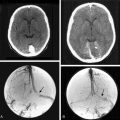

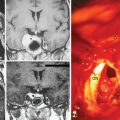

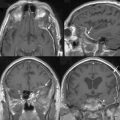

Varying degrees of peritumoral brain edema are observed in approximately two thirds (46%–92%) of meningiomas.27,28 The degree of edema can vary from mild to severe. Severe peritumoral edema will further increase the intracranial pressure and will interfere with brain function, and in some of the cases symptomatic brain edema is the presenting symptom. The exact cause and the pathophysiology of edema associated with meningiomas are under investigation. Physical factors such as tumor compression, parasitization of the pial vasculature, and biological properties of the tumor such as presence of brain invasion; high histologic grade; secretory, microcystic, and/or angiomatous histopathology; and high vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression have all been suggested as the cause of edema.28 Peritumoral brain edema results in symptomatology and complicates surgery, and its presence is associated with a worse surgical outcome; therefore it should be promptly managed in meningioma patients. Since its first application in 1952, corticosteroids have been the mainstay in the treatment of peritumoral brain edema in brain tumors. Corticosteroids are used in all intracranial tumors, regardless of the histopathology. The mode of action is not known but in cases of cytotoxic brain edema corticosteroids decrease the rate of edema formation without affecting its clearance.29,30

A decrease in capillary permeability becomes manifest within the first hour after administration.30 Dexamethasone is the preferred drug owing to its low mineralocorticoid activity. A dose of 16 to 20 mg/day is commonly used; however, it may be increased to up to 100 mg/day. With prolonged use, however, significant side effects overshadow the benefits of steroid treatment. These side effects include immunosuppression, iatrogenic Cushing syndrome, diabetes, gastrointestinal problems, osteoporosis, myopathy, impaired wound healing, psychosis, and an enhanced risk of venous thromboembolism. Therefore, steroids should be tapered quickly after surgery.

PREVENTION OF VENOUS THROMBOEMBOLISM

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is common in brain tumor patients. This complication is seen both in the perioperative period and outside this period during the course of the disease. Immobility of patients, such as in the case of hemiplegia, greatly increases the risk. Deep venous thrombosis may result in pulmonary embolism, which may be fatal in up to 34% of patients.31 The incidence of symptomatic deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism outside the perioperative period was reported to reach 20% in patients with high-grade gliomas. The risk of venous thromboembolism is reported to be significantly high in meningioma patients, more so than most other brain tumors.32–35 The cause and the pathophysiology of VTE in brain tumor patients are not clear. Both clinical and local and systemic biochemical factors are thought to play a role. Clinical factors include prolonged immobilization during surgery, in the postoperative hospital stay and due to motor deficits resulting in venous stasis in the lower extremities such as hemiparesis. Release of procoagulant and fibrinolysis inhibiting factors from the tumor and the surrounding brain parenchyma are thought to result in a low-grade disseminated intravascular coagulation. Also, the use of high-dose corticosteroids is thought to play a role in the development of this procoagulant state.

The current standard for VTE is early patient mobilization, early institution of passive range-of-motion exercises, use of subcutaneous heparin treatment, and use of pneumatic compression boots. The use of pneumatic compression boots is reported to decrease the incidence of VTE by 50%.36,37 Addition of low-dose heparin treatment results in a 38% further relative risk reduction.38 A recent report has confirmed that VTE occurs in fewer than 5% of patients in the postoperative period if dual modality VTE prophylaxis is instituted.39 Gerber and colleagues have reported that this rate is lower than the rate in high-grade glioma patients receiving similar VTE prophylaxis. The risk of postoperative intracranial hemorrhage is the main concern during subcutaneous heparin treatment. In a population undergoing elective hip arthroplasty, treatment with 30 mg of enoxaparin twice daily resulted in an 11% incidence of significant intracranial hemorrhage. Three published reports indicate 3%, 6%, and 20% incidences of intracranial hemorrhage.39–41

PERIOPERATIVE CARE IN THE ELDERLY

The incidence of meningiomas increases with age, and these patients are more commonly diagnosed today owing to the advancements in diagnostic modalities. More than a thousand cases of meningiomas in the elderly have been reported in the literature, and the studies have concluded that the outcome of meningioma surgery in the elderly is less satisfactory and the complication rate is higher. This poorer outcome, however, is not related to intrinsic properties of tumors in the elderly, but to the general health status of the patient. The outcome of meningioma surgery in the elderly is comparable to the younger population in the absence of comorbidities and severe neurologic symptomatology. Poor general health was a significant factory in the majority of published reports. Preoperative health, as assessed with the American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) classification scheme, and preoperative patient functionality, which is measured with the Karnofsky performance scoring, were found useful in evaluating the risk. ASA classes of 3 and 4 and KPS of 60 or less were associated with higher mortality and morbidity in elderly meningioma patients.42 Therefore, efficient perioperative care and avoidance of risks is of great importance in elderly meningioma patients.

[1] Chow S.Y., Hsi M.S., Tang L.M., Fong V.H. Epilepsy and intracranial meningiomas. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi (Taipei). 1995;55:151-155.

[2] Giombini S., Solero C.L., Lasio G., Morello G. Immediate and late outcome of operations for Parasagittal and falx meningiomas. Report of 342 cases. Surg Neurol. 1984;21:427-435.

[3] Giombini S., Solero C.L., Morello G. Late outcome of operations for supratentorial convexity meningiomas. Report on 207 cases. Surg Neurol. 1984;22:588-594.

[4] Lieu A.S., Howng S.L. Intracranial meningiomas and epilepsy: incidence, prognosis and influencing factors. Epilepsy Res. 2000;38:45-52.

[5] Ramamurthi B., Ravi B., Ramachandran V. Convulsions with meningiomas: incidence and significance. Surg Neurol. 1980;14:415-416.

[6] Rohringer M., Sutherland G.R., Louw D.F., Sima A.A. Incidence and clinicopathological features of meningioma. J Neurosurg. 1989;71:665-672.

[7] Yao Y.T. Clinicopathologic analysis of 615 cases of meningioma with special reference to recurrence. J Formos Med Assoc. 1994;93:145-152.

[8] Chan R.C., Thompson G.B. Morbidity, mortality, and quality of life following surgery for intracranial meningiomas. A retrospective study in 257 cases. J Neurosurg. 1984;60:52-60.

[9] Chozick B.S., Reinert S.E., Greenblatt S.H. Incidence of seizures after surgery for supratentorial meningiomas: a modern analysis. J Neurosurg. 1996;84:382-386.

[10] van Breemen M.S., Wilms E.B., Vecht C.J. Epilepsy in patients with brain tumours: epidemiology, mechanisms, and management. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:421-430.

[11] Kawaguchi T., Kameyama S., Tanaka R. Peritumoral edema and seizure in patients with cerebral convexity and parasagittal meningiomas. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 1996;36:568-573. discussion 573–4

[12] Fishman R.A., Chan P.H. Metabolic basis of brain edema. Adv Neurol. 1980;28:207-215.

[13] Prioleau G.R., Fishman R.A., Chan P.H. Induction of brain edema by fatty acids in vivo. Trans Am Neurol Assoc. 1979;104:147-150.

[14] Glantz M.J., Cole B.F., Forsyth P.A., et al. Practice parameter: anticonvulsant prophylaxis in patients with newly diagnosed brain tumors. Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2000;54:1886-1893.

[15] Cohen N., Strauss G., Lew R., et al. Should prophylactic anticonvulsants be administered to patients with newly-diagnosed cerebral metastases? A retrospective analysis. J Clin Oncol. 1988;6:1621-1624.

[16] De Santis A., Villani R., Sinisi M., et al. Add-on phenytoin fails to prevent early seizures after surgery for supratentorial brain tumors: a randomized controlled study. Epilepsia. 2002;43:175-182.

[17] Sirven J.I., Wingerchuk D.M., Drazkowski J.F., et al. Seizure prophylaxis in patients with brain tumors: a meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:1489-1494.

[18] Tremont-Lukats I.W., Ratilal B.O., Armstrong T., Gilbert M.R. Antiepileptic drugs for preventing seizures in people with brain tumors. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008. CD004424

[19] De Pasquet E.G., Gaudin E.S., Bianchi A., De Mendilaharsu S.A. Prolonged and monosymptomatic dysphasic status epilepticus. Neurology. 1976;26:244-247.

[20] Foy P.M., Copeland G.P., Shaw M.D. The incidence of postoperative seizures. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1981;55:253-264.

[21] Karceski S., Morrell M.J., Carpenter D. Treatment of epilepsy in adults: expert opinion, 2005. Epilepsy Behav. 2005;7(Suppl. 1):S1-64. quiz S65–7

[22] Wick W., Menn O., Meisner C., et al. Pharmacotherapy of epileptic seizures in glioma patients: who, when, why and how long? Onkologie. 2005;28:391-396.

[23] Maschio M., Albani F., Baruzzi A., et al. Levetiracetam therapy in patients with brain tumour and epilepsy. J Neurooncol. 2006;80:97-100.

[24] Newton H.B., Goldlust S.A., Pearl D. Retrospective analysis of the efficacy and tolerability of levetiracetam in brain tumor patients. J Neurooncol. 2006;78:99-102.

[25] Perry J.R., Sawka C. Add-on gabapentin for refractory seizures in patients with brain tumours. Can J Neurol Sci. 1996;23:128-131.

[26] Vecht C.J., van Breemen M. Optimizing therapy of seizures in patients with brain tumors. Neurology. 2006;67:S10-S13.

[27] Maiuri F., Gangemi M., Cirillo S., et al. Cerebral edema associated with meningiomas. Surg Neurol. 1987;27:64-68.

[28] Perry A., Gutmann D.H., Reifenberger G. Molecular pathogenesis of meningiomas. J Neurooncol. 2004;70:183-202.

[29] Ito U., Reulen H.J., Tomita H., et al. A computed tomography study on formation, propagation, and resolution of edema fluid in metastatic brain tumors. Adv Neurol. 1990;52:459-468.

[30] Shapiro W.R., Hiesiger E.M., Cooney G.A., et al. Temporal effects of dexamethasone on blood-to-brain and blood-to-tumor transport of 14C-alpha-aminoisobutyric acid in rat C6 glioma. J Neurooncol. 1990;8:197-204.

[31] Horlander K.T., Mannino D.M., Leeper K.V. Pulmonary embolism mortality in the United States, 1979–1998: an analysis using multiple-cause mortality data. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1711-1717.

[32] Levi A.D., Wallace M.C., Bernstein M., Walters B.C. Venous thromboembolism after brain tumor surgery: a retrospective review. Neurosurgery. 1991;28:859-863.

[33] Sawaya R., Zuccarello M., Elkalliny M., Nishiyama H. Postoperative venous thromboembolism and brain tumors: Part I. Clinical profile. J Neurooncol. 1992;14:119-125.

[34] Sawaya R.E., Ligon B.L. Thromboembolic complications associated with brain tumors. J Neurooncol. 1994;22:173-181.

[35] Valladares J.B., Hankinson J. Incidence of lower extremity deep vein thrombosis in neurosurgical patients. Neurosurgery. 1980;6:138-141.

[36] Bucci M.N., Papadopoulos S.M., Chen J.C., et al. Mechanical prophylaxis of venous thrombosis in patients undergoing craniotomy: a randomized trial. Surg Neurol. 1989;32:285-288.

[37] Turpie A.G., Hirsh J., Gent M., et al. Prevention of deep vein thrombosis in potential neurosurgical patients. A randomized trial comparing graduated compression stockings alone or graduated compression stockings plus intermittent pneumatic compression with control. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149:679-681.

[38] Iorio A., Agnelli G. Low-molecular-weight and unfractionated heparin for prevention of venous thromboembolism in neurosurgery: a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2327-2332.

[39] Gerber D.E., Segal J.B., Salhotra A., et al. Venous thromboembolism occurs infrequently in meningioma patients receiving combined modality prophylaxis. Cancer. 2007;109:300-305.

[40] Gerlach R., Scheuer T., Beck J., et al. Risk of postoperative hemorrhage after intracranial surgery after early nadroparin administration: results of a prospective study. Neurosurgery. 2003;53:1028-1034. discussion 1034–5

[41] Kalfas I.H., Little J.R. Postoperative hemorrhage: a survey of 4992 intracranial procedures. Neurosurgery. 1988;23:343-347.

[42] Caroli M., Locatelli M., Prada F., et al. Surgery for intracranial meningiomas in the elderly: a clinical-radiological grading system as a predictor of outcome. J Neurosurg. 2005;102:290-294.