Chapter 17 Periodic Limb Movements in Sleep

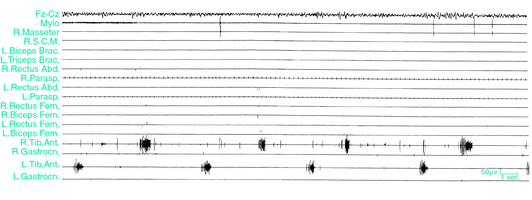

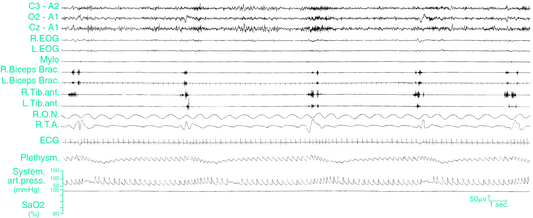

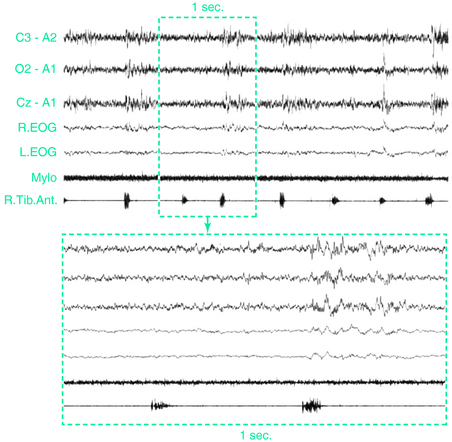

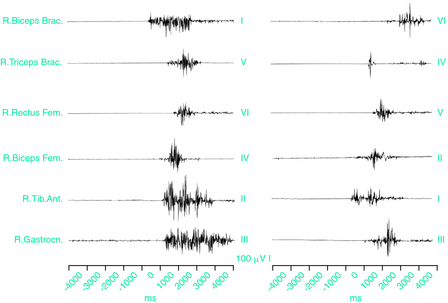

Periodic limb movements during sleep (PLMS) are involuntary, repetitive, stereotypic, short-lasting segmental movements of the lower and sometimes upper limbs. These are commonly described as consisting of a dorsiflexion of the big toe with fanning of the small toes, accompanied by flexion at the ankles, knees, and thighs (Fig, 17-1), although recent studies have indicated a wider variety of movement characteristics not limited to these classic physiologic flexor movements.1,2 Each movement lasts 0.5 to 10 seconds and occurs at intervals of 5 to 90 seconds, with a remarkable periodicity of approximately 20 to 40 seconds.3-6 Movements often involve both legs but may predominate in one leg or alternate between legs (Fig. 17-2). PLMS were first described by Symonds7 under the term “nocturnal myoclonus” (NM). Symonds reported a series of different motor phenomena occurring in sleep, which shared the common feature of muscular contractions of the extremities and, in the absence of polygraphic recordings, postulated an epileptic origin of the jerks. In the mid-1960s, Lugaresi and colleagues3 first recorded NM polygraphically in patients with restless legs syndrome (RLS) and other neurologic diseases and published a series of studies on its electroencephalographic and electromyelographic correlates. In 1980, Coleman and coworkers8 suggested the term “periodic movements in sleep” because the muscular contractions characterizing NM are not, in general, truly myoclonic and usually have muscle potentials longer than those characteristic of myoclonus (i.e., <250 milliseconds). The subsequent terms “periodic leg movements in sleep” and the most recent term “periodic limb movements in sleep” used by the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD)9 emphasize the observation that PLMS are usually present in the legs but that the arms may also be involved10 (Fig. 17-3).

That PLMS in a few patients may become pathological was recognized by the inclusion of the periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD) in the first International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD) published in 1990.11 At that time, PLMD diagnosis required a PLMS index of five movements per hour or more, associated with an otherwise unexplained sleep-wake complaint, impacting either sleep continuity (insomnia) or daytime functioning (sleepiness) and in the absence of concurrent conditions or diseases accounting for the symptoms. Some clinicians criticize the validity and specific usefulness of this distinct diagnostic category, noting that, if it exists, it affects few patients. They suggest that patients must exhibit a clear perception of leg movements causing disruption of the patient’s or sleeping partner’s sleep for a diagnosis of PLMD.12 The update for Version 2 of the ICSD altered the diagnostic criteria for PLMD in three major ways. First, it suggested that for adults a frequency of greater than 15 per hour was required to be considered abnormal. Second, it emphasized excluding leg movements associated with end-of-sleep disordered breathing events. And third, it required PLMD severity judgment to be based on the clinical context rather than an absolute rate of PLMS.9

Epidemiology

Although most frequently associated with RLS, PLMS do occur in healthy people.13,14 PLMS may begin at any age, but in healthy adults they appear to be relatively uncommon until age 40 and then increase markedly with age.5,13,15 The prevalence of PLMS in all adults has been estimated at 5% to 6% in normal subjects13 and up to 18% in sleep disorder clinic populations.16–19 Forty-five percent of normal individuals over 65 may have a PLMS index of greater than 5,12 with an equal distribution among men and women. PLMS can show significant variability across nights,13,20–22 suggesting caution in drawing conclusions from single-night studies in individuals with mild forms of PLMS,23 especially because it seems to have little effect on PLMD severity classification or clinical treatment decisions.22

Normal children seem less likely to have PLMS.14,24,25 In a select population of children at increased risk for having a sleep disorder, the prevalence of isolated PLMS was only 1.2%.26 Limited data indicate that PLMD appear, however, to be common in children with restless legs syndrome (RLS), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, oppositional disorders, and Williams syndrome.24,25,27–29 As in adults, PLMD and RLS in children are two separate but related entities. Children with PLMD and a family history of RLS are considered to be at risk for having or developing RLS.30

Polysomnographic Features

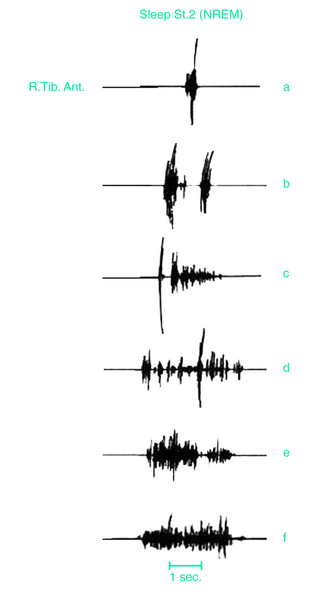

The presence of PLMS is assessed by polysomnographic (PSG) recordings using two surface electrodes placed over both anterior tibialis muscles according to standard criteria.31 Methods for recording and scoring PLMS currently accepted are based on the amplitude of anterior tibialis electromyography (EMG). Each event starts when the EMG amplitude exceeds 8 μV above baseline and ends when the amplitude remains below 2 μV above baseline for at least 0.5 second. The movements must be 0.5 to 10 seconds in duration. A sequence of 4 or more such movements during any sleep stage separated by an interval of at least 5 seconds and not more than 90 seconds is considered PLMS.6 Clinicians have often set a PLMS index of greater than 5 movements per hour of sleep or higher as significant, although this figure may be low, especially in the elderly.11,21 More recent standards set the criteria at greater than 15 movements per hour for adults while remaining at greater than 5 per hour for children.9 One study indicated that for healthy adults younger than 40 years, PLMS generally occurred at rates less than 5 per hour, but adults over age 40 showed rates rapidly increasing with age, with an average of 15 per hour in the 50- to 59-year-old age group and 20 per hour among those over age 60.15 On PSG recordings, the EMG activity often begins with a myoclonic jerk, followed, after a short interval, by a tonic contraction. In rare cases, the initial myoclonic jerk is lacking. More often, repeated myoclonic jerks occur at the beginning of each single movement (Fig. 17-4). Occasionally, repetitive, small-amplitude rhythmic activity may be found in the intervals between PLMS.32

The use of actigraphy for PLMS assessment has been reported,33 and actigraphic techniques34 have also been proposed as a practical and reliable tool for community studies and for automatic detection of PLMS.35,36 This method, however, awaits further validation before its use becomes widespread. Many clinicians are looking for novel, low-cost devices for PLMS testing at home.37

Periodic Limb Movement in Sleep Distribution During the Night and in the Different Sleep Stages

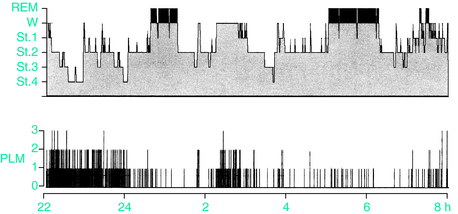

PLMS are most frequent during non–rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep stages 1 and 2. The movements become less frequent and the interval between movements becomes longer as sleep deepens along the NREM sleep stages.5,38 PLMS display a pattern of progressive decline alongside the exponential decline in slow wave activity throughout the night.39 PLMS are maximally suppressed during REM sleep, when the relative frequency is as low as during slow-wave sleep (SWS), movement duration is even shorter, and the intermovement intervals are longer5,38 (Fig. 17-5).

In patients in whom PLMS are found during sleep, PLMS of the same type may occur during quiet wakefulness, before sleep onset, or in the course of nocturnal waking episodes.3,38,40 The movements during wakefulness have been called periodic limb movements while awake (PLMW) or dyskinesia while awake (DWA). PLMW appear especially in patients with RLS, and, at least for this kind of patients, it is recommended to score PLM during both wakefulness and sleep to get a more complete picture of the motor disturbance.41

Two distinct patterns of PLMS activity have been identified.42 In the type 1 pattern, PLMS activity is initially high on falling asleep and then decreases across the remainder of the night with the majority of the activity occurring during the first half of the night; this distribution is typical of patients with either PLMS alone or PLMS associated with RLS. In patients with RLS, PLMS peaks between 11:00 P.M. and 4:00 a.m., showing an acrophase at approximately 3:00 a.m., while the lowest values are between 9:00 A.M. and 3:00 P.M.43–45 In the type 2 pattern, PLMS activity is relatively evenly distributed across the night with slightly greater activity in the middle of the night; this is typical of narcoleptic patients and patients with obstructive sleep apnea.42,46

PLMS may also vary with body position in sleep, with a significant tendency of a series of movements to terminate soon before body position changes and a trend for a series to begin soon after position changes.47

Periodic Limb Movements in Sleep and Arousal

PLMS may be associated with no changes in the electroencephalogram (EEG) and no other evidence of arousal or may instead lead to partial or full arousals (Fig. 17-6). EEG correlates of PLMS are K-complexes, K-alpha complexes, brief bursts of alpha activity, or other cortical and subcortical arousals.3,4,39 Arousals that are associated with PLMS (PLMS arousals) are calculated according to the arousal scoring rules of the American Sleep Disorders Association (ASDA).48

Microstructural analysis of EEG shows that in NREM sleep, the timing and location of arousal-related EEG transients are arrayed in a pseudoperiodic rhythm known as the cyclic alternating pattern (CAP).49 The CAP modulates several pathological phenomena and the great majority of PLMS are associated with phase A of the CAP.50

The sleep structure varies between those with PLMS alone and those with RLS. Patients with isolated PLMS in sleep have more frequent arousals associated with the PLMS than do patients with RLS and PLMS. However, patients with RLS spend significantly more time in wake-after-sleep-onset, have more arousals not associated with any sleep-related event, and more REM, but less stage 1 NREM, sleep than do those with isolated PLMS.51

Generally, PLMS not associated with visible EEG arousals or microarousals are considered to have little effect on sleep quality or daytime alertness,52,53 but a cause-effect relationship between number of arousals and daytime somnolence is not yet well established.5,54 Moreover, the time relationship of the EEG arousals with the leg movements varies: arousals or microarousals can follow the limb movements but can also precede or accompany them,55,56 suggesting that arousals are not simply the consequence of PLMS and that probably EEG arousals and PLMS are separate expressions of a common mechanism.57 The persistence of arousals after suppression of PLMS by L-DOPA41,55 and apomorphine58 supports the hypothesis that the EEG events are a distinct phenomenon, independent of PLMS and not related to the dopaminergic system. Therefore, the PLMS should be considered not simply a motor phenomenon occurring periodically and inducing sleep fragmentation but the expression of an underlying arousal disorder related to dysfunction of the oscillatory networks regulating the cyclic arousability of the sleepy brain.56

It is increasingly clear that central nervous system–orienting systems may be activated even without visible EEG changes. So PLMS may be associated with pure autonomic activation alone, in the absence of an EEG arousal as defined by the ASDA standards.59,60 Spectral EEG and heart rate (HR) analyses at the time of PLMS in patients with RLS and/or PLMD revealed a wide variety of complex and stereotyped variations in cortical activity and heart rate, associated with the PLMS. These included an increase in heart rate and delta band EEG activity before the PLM, which were independent of the presence of microarousals.61,62 The amplitude of the heart rate changes associated with PLMS varies with age.63 The same stereotyped pattern is common in PLMS and in spontaneous or stimuli-induced arousals.62 The concomitant cerebral and autonomic responses before and during PLM suggest that PLMS do not trigger cardiac and EEG activation but are parts of the entire arousal response, which recruits several neural networks from a common generator, probably located in the brainstem and projecting up to a cortical level.59,61,64 The different expression of arousal responses associated with the PLMS may finally mean that analysis of “cortical arousal” as proposed by ASDA criteria may not allow full insight into the real sleep fragmentation occurring in patients with PLMS.

Pathophysiology of Periodic Limb Movements in Sleep

The exact origin and pathophysiology of the PLMS are unknown. Although reduced cortical inhibition65,66 and impairment of cortical-subcortical motor structures, in particular motor inhibitory pathways67 have been reported in RLS, a cortical origin for the PLMS is unlikely, because electrophysiologic studies demonstrated the lack of any Bereitschaftspotential preceding the PLMS.32,68

It has been hypothesized that PLMS may result from rhythmical fluctuations of reticular excitability50,64 and that suprasegmental disinhibition during sleep may provoke PLMS.68–71 Neurophysiologic studies support the hypothesis that the underlying mechanisms are active at the pontine level or rostral to it.72 In PLMS patients, the excitability of the R2 response of the blink reflex was markedly enhanced.73

High-resolution functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) in patients with PLMS and RLS showed significant activation of the red nucleus and the brainstem and no apparent involvement of the cortex.71

Because of their resemblance to the Babinski response and the normality of lower and upper extremity somatosensory evoked responses and brainstem auditory evoked responses, some investigators attribute the PLMS to suppression of supraspinal descending inhibitory pathways on the pyramidal tract.74,75

The observation that PLMS may be present below a complete spinal cord lesion,70,76–78 such as during midthoracic epidural or spinal anesthesia, indicates that PLMS can be directly generated in the spinal cord.79 Patients with PLMS and uremic RLS have increased spinal flexor reflexes and significantly increased spinal cord excitability particularly during sleep.80,81

On the other hand, the peripheral nervous system has been implicated on the basis of findings of small-fiber neuropathy in patients with primary or secondary RLS,32,82–86 but it is still an unresolved question whether the peripheral dysfunction triggers PLMS or is simply coincidental. Pacing of PLMS by repetitive electrical stimulation of the peroneal nerve32 indicates that peripheral sensory afferents play a role in triggering the PLMS. Although abnormal electromyographic activity of limb movements during wakefulness in RLS has been found to spread along propriospinal pathways intrinsic to the cord,68 no propriospinal pattern of propagation was found in two studies of PLMS showing that the leg muscles are the most frequently involved with no hierarchical order and no caudal or rostral propagation typical of propriospinal myoclonus.1,2 Muscle activation did not show a consistent recruitment pattern from one PLMS to another, indicating the engagement of different, independent, and sometimes unsynchronized generators for each PLMS (Fig. 17-7). These data suggested an abnormal hyperexcitability along the entire spinal cord, especially in its lumbosacral and cervical segments, as a primary cause of PLMS, triggered by state-dependent sleep-related factors located at a supraspinal level.1,2 On the other hand, axial jerks with a propriospinal type of propagation during relaxed wakefulness giving place to typical PLMS as soon as spindle activity shows up on the EEG recordings have been reported in RLS.87

The efficacy of dopaminergic drugs88,89 and opioids90–92 in reducing PLMS suggests an involvement of either the dopaminergic or the opioid system in their pathogenesis. In particular, the fact that PLMS are more frequent in RLS, narcolepsy, and most probably in REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD)93,94 raises the possibility of an impaired central dopaminergic transmission.94 The association between PLMS and Parkinson’s disease, although not as strong as one would have expected, also suggests that dopaminergic systems may be involved in the PLMS.95 Neuroimaging studies in RLS and PLMS, albeit controversial, disclose some evidence of an underlying dopaminergic pathomechanism of PLMS.96–101 Finally, in view of the role of iron in the origin of RLS, it was observed that patients with RLS and low serum ferritin have higher PLMS indexes.102

Periodic Limb Movements in Sleep (PLMS) in Sleep Disorders and Other Diseases

PLMS can occur as an isolated phenomenon in subjects without any sleep complaint4,103 or may be associated with a wide variety of medical, neurologic, and sleep disorders.8 PLMS were first polygraphically documented in the RLS,3 and more than 80% of patients with RLS experience PLMS.55 Elevated PLMS indices are found in up to 90% of narcoleptics over the age of 60 years.8,94 PLMS have also been reported in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS),104 who may have PLMS independent of the apneic episodes105 and in more subtle forms of sleep disordered breathing (i.e., the upper airway resistance syndrome).106 Depending on OSAS severity, PLMS may either increase or decrease following treatment of sleep apnea with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), which could unmask an underlying PLMD.107

PLMS are also highly prevalent in RBD,108,109 insomniac,3,8 and hypersomniac patients. Nightmare sufferers present with an elevated PLMS index.110 Patients with PLMS are more likely to show a wide range of depressive symptoms, anxiety, and social alienation and diminished mental concentration (as measured by the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory [MMPI]111,112). An association between PLMS and post-traumatic stress disorder has also been reported.113,114 PLMS occur in children with beta-thalassemia and congenital dyserythropoietic anemia115 and fibromyalgia.116 These observations are, however, often anecdotal, and in the absence of controlled studies and given the high prevalence of PLMS in the adult and elderly normal population, it is difficult to judge significance of these associations particularly when they occur in older adults.

PLMS are found in 30% of patients with Parkinson’s disease,117–119 in levodopa-responsive hereditary dystonia,120 and multiple system atrophy and corticobasal degeneration.119,121

PLMS have been reported with lesions of the spinal cord,70,76,78,122–124 spinal anesthesia,69,79 radiculopathies,125 motor neuron disease,32 and Isaac and stiff-man syndromes.126 PLMS are particularly prevalent in uremia127 and may occur more frequently during pregnancy, especially in a multiple pregnancy.128

Are Periodic Limb Movements Associated With Clinical Sleep Disturbances?

On the basis of PSG findings, it was suggested that PLMS are not responsible for sleep impairment32 but often represent only an incidental PSG observation. In fact, many studies have found no or minimal correlation between PLMS and either objective or subjective measures of sleep-wake disturbances.13,21,23,54,123–131 The similar high prevalence of PLMS in several sleep disorders (PLMS occurs in 13% of patients complaining of insomnia and in 7% of those being evaluated for excessive sleepiness) and in the asymptomatic general population speaks against their clinical significance.54,94,132 No significant correlation between PLMS index, PLMS arousal index, and nocturnal sleep parameters, including analysis of the microstructure of sleep, was found in patients complaining of insomnia, indicating that the relation of PLMS to a subjective complaint of sleep disturbance is neither obvious nor simple.54,133 In patients with sleep-disordered breathing, there is no association between the rate of PLMS and excessive daytime sleepiness.134 RLS symptoms are often found to correlate with PLMS rates,135,136 but this is not always the case.130

These findings all emphasize that, in contrast to RLS, the presence of PLMS per se is not necessarily of clinical significance. In contrast, some clinicians suggest that PLMS may be an important cause of insomnia5,16 and that their clinical relevance is related to the EEG signs of arousal they produce:5 when no arousals are present, patients have no sleep-wake complaints. PLMS may also provide a prognostic indicator of mortality in renal failure,137 and a possible relationship between PLMS in sleep and hypertension and cardiovascular disease was reported: patients with severe congestive heart failure138 and hypertension have a moderately severe PLMS index as opposed to controls, and the prevalence of PLMS in sleep is directly proportional to the severity of the hypertension.139 Moreover, many PLMS events, when they occur, are associated with transient increases in blood pressure.140

Measurement and Analysis of Leg Movement Periodicity

The definition of leg movement (LM) periodicity has changed little since 1982, when Coleman and colleagues5 collected data from a limited number of subjects, using visual analysis of paper PSG recordings; the Atlas and Scoring (1993) rules141 and the newer IRLSSG-WASM6 or AASM30,142 criteria all define PLMS as repetitive (at least four) muscular jerks lasting from 0.5 to 5 or 10 seconds, separated by an interval ranging from 5 to 90 seconds. In these rules, the character of periodicity is determined by the appearance of sequences of LMs with criteria defined a priori.

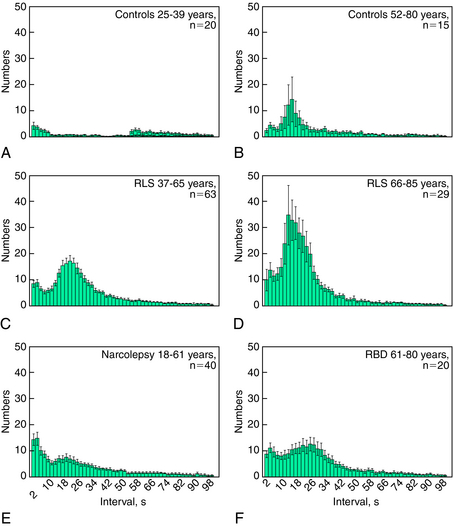

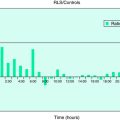

More recently, in contrast to the intuitive and rational method applied by Coleman and coworkers,5 a more empirical statistical approach has been applied for the characterization of PLMS.142 This approach takes into consideration a wide spectrum of sleep phasic activities of the tibialis anterior muscles, including nonperiodic LMs. In this approach, all intermovement intervals are measured and plotted as a distribution histogram. This type of graphic representation identifies, in patients with RLS, two main peaks in the statistical distribution representing two separate populations of intermovement intervals, only one of which (interval lengths of 10 to 90 seconds) corresponds to the classically defined periodic leg movements. The second group with interval lengths of less than 10 seconds appears to be a statistically separate population with its own distinct mode. Figure 17-8 shows examples of this type of analysis demonstrating the bimodal distribution of the frequencies of intermovement intervals. These data presented come from: two age groups of patients with RLS (see Fig. 17-8C, D), normal controls (see Fig. 17-8A, B), and other groups of patients (see Fig. 17-8E, F). A periodicity index can be calculated143 that quantifies the proportion of all intermovement intervals with length L greater than 10 but no more than 90 seconds (10 < L = 90 seconds) that are also preceded and followed by another interval within the same length limits (this is equivalent to a mini-series of four LMs all separated by intervals with length 10 < L = 90 seconds). This index can vary between 0 (absence of periodicity, with none of the intervals having a length between 10 and 90 seconds satisfying the above criterion) to 1 (complete periodicity, with all intervals having a length between 10 and 90 seconds).

The PLMS periodicity index of patients with RLS is influenced by the age of the subjects144 but is independent of the absolute number of PLMS.143 It is known that PLMS can be found in normal control subjects older than 40 years,14 and this phenomenon is clearly visible in Figure 17-8A and B; also, the periodicity index of older normal control subjects shows a significant increase.145 In RLS, the typical intermovement interval is around 24 to 28 seconds before the age of 55 years but at around 14 to 16 seconds after the age of 65 years. In RLS, PLMS index reaches a plateau at 15 to 25 years of age and remains stable up to 65 years, after this age, it shows an important increase. In the same patients, the periodicity index increases progressively up to the age of 35 years and then remains stable up to the age of 85 years.144

Thus, the periodicity index provides a quantitative measure of this important aspect of PLMS that is partially independent of the total number of LMs. It provides a new tool for the comparison of the degrees of PLMS periodicity across clinical conditions and might be used in addition to the widely known PLMS index (i.e., the number of PLMS per hour of sleep). This approach demonstrated that patients with narcolepsy/cataplexy (see Fig. 17-8E) tend to show high values of PLMS index but a periodicity index lower than that found in RLS patients146; similarly, the PLMS periodicity in all sleep stages is lower in patients with REM sleep behavior disorder than those with RLS145 (see Fig. 17-8F). The differences in the periodicity index may reflect difference in the mechanisms for the generation of PLMS in these various conditions. The diagnostic value of PLMS in RLS is sustained by a high sensitivity, but at the same time it is also reduced by a low specificity, because PLMS are also a common finding in other sleep disorders and in healthy elderly subjects. The addition of this new parameter (periodicity index) is a step forward for a better characterization of PLMS in various diseases and may enhance specificity of PLMS assessments for the diagnosis of RLS.

Finally, the correct identification of the periodic phenomenon and its extraction from the nonperiodic activity have a putative neurophysiologic meaning. These two types of activities seem to be accompanied by different levels and time-locked changes in EEG spectral power and heart rate, and evaluation of these differences may inform about underlying neurophysiologic mechanisms producing the movements.147

Differential Diagnosis

PLMS have to be differentiated from other nocturnal involuntary motor phenomena that occur during sleep or at the transition from wakefulness to sleep. Fragmentary myoclonus is physiologic148 and consists of localized muscle potentials of very short duration (10 to 100 milliseconds) arising spontaneously and irregularly, especially in the distal muscles, particularly during stage 1 of NREM sleep and REM sleep. There is often no apparent movement associated with these potentials, but larger ones can cause flickering movements. Its abnormal intensification is called excessive fragmentary hypnic myoclonus (EFHM).149

Sleep starts are nonperiodic muscle contractions simultaneously involving the trunk and the extremities, arising when the subject is falling asleep or during light sleep, frequently associated with a perception of falling.150

Propriospinal myoclonus is a type of spinal myoclonus characterized by rhythmic or arrhythmic spontaneous or sometimes stimulus-sensitive flexion or extension movements of the axial muscles with or without spread to limb muscles.151 The initial myoclonic activity arises in the midthoracic segments and is propagated up and down the spinal cord via slowly conducting pathways, supposedly the propriospinal system. In some cases, propriospinal myoclonus may arise during the sleep-wake transition period.152,153

Alternating leg muscle activation (ALMA) is characterized by a quickly alternating pattern of anterior tibialis activation in all sleep stages or arousals from sleep, at about 1 to 2 Hz, and in sequences lasting several seconds.154 These movements are similar to the reported hypnic foot tremor, also a repetitive cyclical movement that may occur either in one leg or in both.155,156 Both of these movements are quite similar to those categorized as rhythmic movement disorder.30

The differential diagnosis of PLMS should also take into consideration nocturnal leg cramps, which consist of sporadic, painful, spasmodic contractions, usually limited to the calf muscles or to the small muscles of the sole of the foot, brought about by sudden forceful contractions of the lower extremities and relieved by stretching the muscles involved.157

Other pathological motor phenomena in the differential diagnosis of PLMS are RBD158 and nocturnal epileptic seizures, especially the paroxysmal arousals.159

Treatment

A PLMS index of greater than 15 for adults and 5 for children with associated arousals is generally considered an indication for possible treatment provided there is a sleep complaint related to the movements and no other explanation of the events.8 The choice of medication, however, has to take into account that drugs have side effects, and, moreover, many published studies are concerned with treatment of PLMS in patients with RLS.

A combination of regular and slow release levodopa (100 to 200 mg) with a decarboxylase inhibitor (benserazide or carbidopa) before bedtime reduces PLMS with a longer duration response compared with regular release levodopa alone.160 Among dopamine agonists, bromocriptine at a mean dosage of 7.5 mg has been shown to bring subjective relief of RLS symptoms and to reduce the number of PLMS.161 The dopamine agonists pergolide (0.05 to 1.0 mg/daily), pramipexole (0.125 to 2.5 mg/daily), ropinirole (0.25 to 6 mg/daily), and cabergoline (1 to 3 mg/daily) have all been shown effective in the treatment of both RLS and PLMS.160 The irreversible monoamine oxidase inhibitor type B selegiline (10 to 30 mg/daily) and transdermal apomorphine reduced PLMS and improved sleep in parkinsonian patients.160,162 Among the opioids, oxycodone (10 to 15 mg per night) decreased the number of PLMS and arousals and improved sleep efficiency.92

There is controversy regarding the therapeutic effects of benzodiazepines (particularly clonazepam) on PLMS, because of the high variability of the therapeutic response among patients,41 although some studies showed significant decrease in PLMS and/or improved sleep efficiency.163,164 Among the anticonvulsants, carbamazepine (200 to 600 mg) is useful in severe case of PLMS165; others, however, reported no significant modifications of PLMS and related arousals during sleep in patients with RLS.166 Lamotrigine (100 mg/daily), valproate (125 to 600 mg/daily), and gabapentin (300 to 2400 mg/daily) seem to reduce or suppress PLMS and associated sleep fragmentation.167–171 Bupropion, unlike many other antidepressants, reduces PLMS.172 Magnesium may also suppress PLMS,173 and a positive response to melatonin has been hypothetically related to its chronobiotic effects.174

It is worth emphasizing, however, that PLMS per se, in their essential form, do not constitute a clinical problem, do not disturb the patient, do not disrupt sleep, and therefore do not require treatment. Patients with PLMS should only be treated when PLMS can demonstrably be linked to sleep complaints, which requires excluding other sources of sleep dysfunction.

1. Provini F, Vetrugno R, Meletti S, et al. Motor pattern of periodic limb movements during sleep. Neurology. 2001;57:300-304.

2. de Weerd AW, Rijsman RM, Brinkley A. Activity patterns of leg muscles in periodic limb movement. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:317-319.

3. Lugaresi E, Tassinari CA, Coccagna G, et al. Particularités cliniques et polygraphiques du syndrome d’impatience des membres inférieurs. Rev Neurol (Paris). 1965;113:545-555.

4. Lugaresi E, Coccagna G, Gambi D, et al. A propos de quelques manifestations nocturnes myocloniques (nocturnal myoclonus de Symonds). Rev Neurol. 1966;115:547-555.

5. Coleman RM, Roffwarg HP, Kennedy SJ, et al. Sleep-wake disorders based on a polysomnographic diagnosis. A national cooperative study. JAMA. 1982;247:997-1003.

6. Zucconi M, Ferri R, Allen R, et al. The official World Association of Sleep Medicine (WASM) standards for recording and scoring periodic leg movements in sleep (PLMS) and wakefulness (PLMW) developed in collaboration with a task force from the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group (IRLSSG). Sleep Med. 2006;7:175-183.

7. Symonds CP. Nocturnal myoclonus. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1953;16:166-171.

8. Coleman RM, Pollak CP, Weitzman ED. Periodic movements in sleep (nocturnal myoclonus): Relation to sleep disorders. Ann Neurol. 1980;8:416-421.

9. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders: Diagnostic and Coding Manual, rev, 2. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2005.

10. Chabli A, Michaud M, Montplaisir J. Periodic arm movements in patients with the restless legs syndrome. Eur Neurol. 2000;44:133-138.

11. Diagnostic Classification Steering Committee of the American Sleep Disorders Association. The International Classification of Sleep Disorders: Diagnostic and Coding Manual. Rochester, MN: American Sleep Disorders Association, 1990.

12. Silber MH. Commentary on controversies in sleep medicine. Montplaisir et al.: Periodic leg movements are not more prevalent in insomnia or hypersomnia but are specifically associated with sleep disorders involving a dopaminergic mechanism. Sleep Med. 2001;2:367-369.

13. Ancoli-Israel S, Kripke DF, Klauber MR, et al. Periodic limb movements in sleep in community-dwelling elderly. Sleep. 1991;14:496-500.

14. Bixler EO, Kales A, Vela-Bueno A, et al. Nocturnal myoclonus and nocturnal myoclonic activity in the normal population. Res Commun Chem Pathol Pharmacol. 1982;36:129-140.

15. Pennestri MH, Whittom S, Adam B, et al. PLMS and PLMW in healthy subjects as a function of age: Prevalence and interval distribution. Sleep. 2006;29:1183-1187.

16. Guilleminault C, Raynal D, Weitzman ED, et al. Sleep related periodic myoclonus in patients complaining of insomnia. Trans Am Neur Assoc. 1975;100:19-21.

17. Soldatos CR, Bixler EO, Kales A, et al. Prevalence of myoclonus nocturnus in chronic insomnia. Sleep Res. 1976;5:189.

18. Kales A, Bixler EO, Soldatos CR, et al. Biopsychobehavioral correlates of insomnia, part 1: role of sleep apnea and nocturnal myoclonus. Psychosomatics. 1982;23:589-600.

19. Coleman R, Bliwise D, Sajben N, et al. Epidemiology of periodic movements during sleep. In: Guilleminault C, Lugaresi E, editors. Sleep/Wake Disorders: Natural History, Epidemiology, and Long-term Evolution. New York: Raven Press; 1983:217-229.

20. Bliwise DL, Carskadon MA, Dement WC. Nightly variation of periodic leg movements in sleep in middle aged and elderly individuals. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 1988;7:273-279.

21. Dickel MJ, Mosko SS. Morbidity cut-offs for sleep apnea and periodic leg movements in predicting subjective complaints in seniors. Sleep. 1990;13:155-166.

22. Edinger JD, McCall WV, Marsh GR, et al. Periodic limb movement variability in older DIMS patients across consecutive nights of home monitoring. Sleep. 1992;15:156-161.

23. Mosko SS, Dickel MJ, Ashurst J. Night to night variability in sleep apnea and sleep related periodic leg movements in the elderly. Sleep. 1988;11:340-348.

24. Picchietti DL, England SJ, Walters AS, et al. Periodic limb movement disorder and restless legs syndrome in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Child Neurol. 1998;13:588-594.

25. Arens R, Wright B, Elliott J, et al. Periodic limb movement in sleep in children with Williams syndrome. J Pediatr. 1998;133:670-674.

26. Kirk VG, Bohn S. Periodic limb movements in children: Prevalence in a referred population. Sleep. 2004;27:313-315.

27. Chervin RD, Archbold KH. Hyperactivity and polysomnographic findings in children evaluated for sleep-disordered breathing. Sleep. 2001;24:313-320.

28. Chervin RD, Archbold KH, Dillon JE, et al. Association between symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, restless legs, and periodic leg movements. Sleep. 2002;25:213-218.

29. Crabtree VM, Ivanenko A, O’Brien LM, et al. Periodic limb movement disorder of sleep in children. J Sleep Res. 2003;12:73-81.

30. Allen RP, Picchietti D, Hening WA, participants in the Restless Legs Syndrome Diagnosis and Epidemiology workshop at the National Institutes of Health in collaboration with members of the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group. Restless legs syndrome: diagnostic criteria, special considerations, and epidemiology: a report from the RLS Diagnosis and Epidemiology workshop at the National Institutes of Health. Sleep Med. 2003;4:101-119.

31. Walters AS, Lavigne G, Hening W, et al. The scoring of movements in sleep. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3:155-167.

32. Lugaresi E, Cirignotta F, Coccagna G, et al. Nocturnal myoclonus and restless legs syndrome. In: Fahn S, Marsden CD, Van Woert M (eds). Myoclonus. Adv Neurol 1986;43:295-307.

33. Kazenwadel J, Pollmächer T, Trenkwalder C, et al. New actigraphic assessment method for periodic leg movements (PLM). Sleep. 1995;18:689-697.

34. Morrish E, King MA, Pilsworth SN, et al. Periodic limb movement in a community population detected by a new actigraphy technique. Sleep Med. 2002;3:489-495.

35. Wetter TC, Dirlich G, Streit J, et al. An automatic method for scoring leg movements in polygraphic sleep recordings and its validity in comparison to visual scoring. Sleep. 2004;27:324-328.

36. Sforza E, Johannes M, Claudio B. The PAM-RL ambulatory device for detection of periodic leg movements: A validation study. Sleep Med. 2005;6:407-413.

37. Shochat T, Oksenberg A, Hadas N, et al. The KickStripTM: A novel testing device for periodic limb movement disorder. Sleep. 2003;26:480-483.

38. Pollmächer T, Schulz H. Periodic leg movements (PLM): Their relationship to sleep stages. Sleep. 1993;16:572-577.

39. Sforza E, Jouny C, Ibanez V. Time course of arousal response during periodic leg movements in patients with periodic leg movements and restless legs syndrome. Clin Neurophysiol. 2003;114:1116-1124.

40. Montplaisir J, Godbout R, Boghen D, et al. Familial restless legs with periodic movements in sleep: Electrophysiologic, biochemical, and pharmacologic study. Neurology. 1985;35:130-134.

41. Montplaisir J, Lapierre O, Warnes H, et al. The treatment of the restless legs syndrome with or without periodic leg movements in sleep. Sleep. 1992;15:391-395.

42. Culpepper WJ, Badia P, Shaffer JI. Time-of-night patterns in PLMS activity. Sleep. 1992;15:306-311.

43. Hening WA, Walters AS, Wagner M, et al. Circadian rhythm of motor restlessness and sensory symptoms in the idiopathic restless legs syndrome. Sleep. 1999;22:901-912.

44. Michaud M, Dumont M, Selmaoui B, et al. Circadian rhythm of restless legs syndrome: Relationship with biological markers. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:372-380.

45. Trenkwalder C, Hening WA, Walters AS, et al. Circadian rhythm of periodic limb movements and sensory symptoms of restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord. 1999;14:102-110.

46. Montplaisir J, Godbout R, Pelletier G, et al. Restless legs syndrome and periodic movements during sleep. In: Kryger MH, Roth T, Dement WC, editors. Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine. 2. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1994:589-597.

47. Dzvonik ML, Kripke DF, Klauber M, et al. Body position changes and periodic movements in sleep. Sleep. 1986;9:484-491.

48. Atlas Task Force of the American Sleep Disorders AssociationGuilleminault Cchairman. EEG arousals: Scoring rules and examples. Sleep. 1992;15:173-184.

49. Terzano MG, Mancia D, Salati MR, et al. The cyclic alternating pattern as a physiologic component of normal NREM sleep. Sleep. 1985;8:137-145.

50. Parrino L, Boselli M, Buccino GP, et al. The cyclic alternating pattern plays a gate-control on periodic limb movements during non-rapid eye movement sleep. J Clin Neurophysiol. 1996;13:314-323.

51. Eisensehr I, Ehrenberg BL, Noachtar S. Different sleep characteristics in restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder. Sleep Med. 2003;4:147-152.

52. Rosenthal L, Roehrs T, Sicklesteel J, et al. Periodic movements during sleep, sleep fragmentation and sleep-wake complaints. Sleep. 1984;7:326-330.

53. Saskin P, Moldofsky H, Lue FA. Periodic movements in sleep and sleep-wake complaint. Sleep. 1985;8:319-324.

54. Mendelson WB. Are periodic leg movements associated with clinical sleep disturbances? Sleep. 1996;19:219-223.

55. Montplaisir J, Boucher S, Gosselin A, et al. Persistence of repetitive EEG arousals (K-alpha complexes) in RLS patients treated with L-DOPA. Sleep. 1996;19:196-199.

56. Karadeniz D, Ondze B, Besset A, et al. EEG arousals and awakenings in relation with periodic leg movements during sleep. J Sleep Res. 2000;9:273-277.

57. El-Ad B, Chervin RD. The case of a missing PLM. Sleep. 2000;23:450-451.

58. Haba-Rubio J, Staner L, Cornette F, et al. Acute low single dose of apomorphine reduces periodic limb movements but has no significant effect on sleep arousals: A preliminary report. Neurophysiol Clin. 2003;33:180-184.

59. Sforza E, Nicolas A, Lavigne G, et al. EEG and cardiac activation during periodic leg movements in sleep: Support for a hierarchy of arousal responses. Neurology. 1999;52:786-791.

60. Winkelman JW. The evoked heart rate response to periodic leg movements of sleep. Sleep. 1999;22:575-580.

61. Sforza E, Jouny C, Ibanez V. Time-dependent variation in cerebral and autonomic activity during periodic leg movements in sleep: Implications for arousal mechanisms. Clin Neurophysiol. 2002;113:883-891.

62. Ferrillo F, Beelke M, Canovaro P, et al. Changes in cerebral and autonomic activity heralding periodic limb movements in sleep. Sleep Med. 2004;5:407-412.

63. Gosselin N, Lanfranchi P, Michaud M, et al. Age and gender effects on heart rate activation associated with periodic leg movements in patients with restless legs syndrome. Clin Neurophysiol. 2003;114:2188-2195.

64. Lugaresi E, Coccagna G, Mantovani M, et al. Some periodic phenomena arising during drowsiness and sleep in man. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1972;32:701-705.

65. Tergau F, Wischer S, Paulus W. Motor system excitability in patients with restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 1999;52:1060-1063.

66. Entezari-Taher M, Singleton JR, Jones CR, et al. Changes in excitability of motor cortical circuitry in primary restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 1999;53:1201-1205.

67. Quatrale R, Manconi M, Gastaldo E, et al. Neurophysiological study of corticomotor pathways in restless legs syndrome (RLS). Clin Neurophysiol. 2003;114:1638-1645.

68. Trenkwalder C, Bucher SF, Oertel WH, et al. Bereitschaftspotential in idiopathic and symptomatic restless legs syndrome. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1993;89:95-103.

69. Watanabe S, Sakai K, Ono Y, et al. Alternating periodic leg movement induced by spinal anesthesia in an elderly male. Anesth Analg. 1987;66:1031-1032.

70. Yokota T, Hirose K, Tanabe H, et al. Sleep-related periodic leg movements (nocturnal myoclonus) due to spinal cord lesion. J Neurol Sci. 1991;104:13-18.

71. Bucher SF, Seelos KC, Oertel WH, et al. Cerebral generators involved in the pathogenesis of the restless legs syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1997;41:639-645.

72. Wechsler LR, Stakes JW, Shahani BT, et al. Periodic leg movements of sleep (nocturnal myoclonus): An electrophysiological study. Ann Neurol. 1986;19:168-173.

73. Briellmann RS, Rösler KM, Hess CW. Blink reflex excitability is abnormal in patients with periodic leg movements in sleep. Mov Disord. 1996;11:710-714.

74. Smith RC. Relationship of periodic movements in sleep (nocturnal myoclonus) and the Babinski sign. Sleep. 1985;8:239-243.

75. Mosko SS, Nudleman KL. Somatosensory and brainstem auditory evoked responses in sleep-related periodic leg movements. Sleep. 1986;9:399-404.

76. Lee MS, Choi YC, Lee SH, et al. Sleep-related periodic leg movements associated with spinal cord lesions. Mov Disord. 1996;11:719-722.

77. Hartmann M, Pfister R, Pfadenhauer K. Restless legs syndrome associated with spinal cord lesions. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;66:688-689.

78. de Mello MT, Silva AC, Rueda AD, et al. Correlation between K complex, periodic leg movements (PLM), and myoclonus during sleep in paraplegic adults before and after an acute physical activity. Spinal Cord. 1997;35:248-252.

79. Watanabe S, Ono A, Naito H. Periodic leg movements during either epidural or spinal anesthesia in an elderly man without sleep-related (nocturnal) myoclonus. Sleep. 1990;13:262-266.

80. Bara-Jimenez W, Aksu M, Graham B, et al. Periodic limb movements in sleep. State-dependent excitability of the spinal flexor reflex. Neurology. 2000;54:1609-1615.

81. Aksu M, Bara-Jimenez W. State dependent excitability changes of spinal flexor reflex in patients with restless legs syndrome secondary to chronic renal failure. Sleep Med. 2002;3:427-430.

82. Bliwise DL, Ingham RH, Date ES, et al. Nerve conduction and creatinine clearance in aged subjects with periodic movements in sleep. J Gerontol. 1989;44:M164-167.

83. Geminiani F, Marbini A, Di Giovanni G, et al. Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2 with restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 1999;52:1064-1066.

84. Iannaccone S, Zucconi M, Marchettini P, et al. Evidence of peripheral axonal neuropathy in primary restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord. 1995;10:2-9.

85. Polydefkis M, Allen RP, Hauer P, et al. Subclinical sensory neuropathy in late-onset restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 2000;55:1115-1121.

86. Salvi F, Montagna P, Plasmati R, et al. Restless legs syndrome and nocturnal myoclonus: initial clinical manifestation of familial amyloid polyneuropathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1990;53:522-525.

87. Vetrugno R, Plazzi G, Provini F, et al. Propriospinal myoclonus (PSM): A motor phenomenon found in restless legs syndrome (RLS) and different from periodic limb movements during sleep (PLMS). Mov Disord. 2004;suppl 9(19):S120.

88. Montplaisir J, Godbout R, Poirier G, et al. Restless legs syndrome and periodic movements in sleep: Physiopathology and treatment with L-dopa. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1986;9:456-463.

89. Akpinar S. Restless legs syndrome treatment with dopaminergic drugs. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1987;10:69-79.

90. Hening WA, Walters A, Kavey N, et al. Dyskinesias while awake and periodic movements in sleep in restless legs syndrome: Treatment with opioids. Neurology. 1986;36:1363-1366.

91. Trzepacz PT, Violette EJ, Sateia MJ. Response to opioids in three patients with restless legs syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 1984;141:993-995.

92. Walters AS, Wagner ML, Hening WA, et al. Successful treatment of the idiopathic restless legs syndrome in a randomized double-blind trial of oxycodone versus placebo. Sleep. 1993;16:327-332.

93. Schenck CH, Mahowald MW. Polysomnographic, neurologic, psychiatric, and clinical outcome report on 70 consecutive cases with REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD): Sustained clonazepam efficacy in 89.5% of 57 cases. Cleve Clin J Med. 1990;57(suppl):S9-S23.

94. Montplaisir J, Michaud M, Denesle R, et al. Periodic leg movements are not more prevalent in insomnia or hypersomnia but are specifically associated with sleep disorders involving a dopaminergic impairment. Sleep Med. 2000;1:163-167.

95. Happe S, Pirker W, Klosch G, et al. Periodic leg movements in patients with Parkinson’s disease are associated with reduced striatal dopamine transporter binding. J Neurol. 2003;250:83-86.

96. Michaud M, Soucy JP, Chabli A, et al. SPECT imaging of striatal pre- and postsynaptic dopaminergic status in restless legs syndrome with periodic leg movements in sleep. J Neurol. 2002;249:164-170.

97. Staedt J, Stoppe G, Kogler A, et al. Dopamine D2 receptor alteration in patients with periodic movements in sleep (noctunal myoclonus). J Neural Transm. 1993;93:71-74.

98. Ruottinen HM, Partinen M, Hublin C, et al. An FDOPA PET study in patients with periodic limb movement disorder and restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 2000;54:502-504.

99. Trenkwalder C, Walters AS, Hening WA, et al. Positron emission tomographic studies in restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord. 1999;14:141-145.

100. Turjanski N, Lees AJ, Brooks DJ. Striatal dopaminergic function in restless legs syndrome: 18F-dopa and 11C-raclopride PET studies. Neurology. 1999;52:932-937.

101. Tribl GG, Asenbaum S, Happe S, et al. Normal striatal D2 receptor binding in idiopathic restless legs syndrome with periodic leg movements in sleep. Nucl Med Commun. 2004;25:55-60.

102. Sun ER, Chen CA, Ho G, et al. Iron and the restless legs syndrome. Sleep. 1998;21:381-387.

103. Lugaresi E, Berti-Ceroni G, Coccagna G, et al. Mioclonie notturne sintomatiche. Sistema Nervoso. 1967;19:71-80.

104. Fry JM, DiPhillipo MA, Pressman MR. Periodic leg movements in sleep following treatment of obstructive sleep apnea with nasal continuous positive airways pressure. Chest. 1989;96:89-91.

105. Carelli G, Krieger J, Calvi-Gries F, et al. Periodic limb movements and obstructive sleep apneas before and after continuous positive airway pressure treatment. J Sleep Res. 1999;8:211-216.

106. Exar EN, Collop NA. The association of upper airway resistance with periodic limb movements. Sleep. 2001;24:188-192.

107. Baran AS, Richert AC, Douglass AB, et al. Change in periodic limb movement index during treatment of obstructive sleep apnea with continuous positive airway pressure. Sleep. 2003;26:717-720.

108. Lapierre O, Montplaisir J. Polysomnographic features of REM sleep behavior disorder: Development of a scoring method. Neurology. 1992;42:1371-1374.

109. Fantini ML, Michaud M, Gosselin N, et al. Periodic leg movements in REM sleep behavior disorder and related autonomic and EEG activation. Neurology. 2002;59:1889-1894.

110. Germain A, Nielsen TA. Sleep pathophysiology in posttraumatic stress disorder and idiopathic nightmare sufferers. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:1092-1098.

111. Aikens JE, Vanable PA, Tadimeti L, et al. Differential rates of psychopathology symptoms in periodic limb movement disorder, obstructive sleep apnea, psychophysiological insomnia, and insomnia with psychiatric disorder. Sleep. 1999;22:775-780.

112. Vandeputte M, de Weerd A. Sleep disorders and depressive feelings: A global survey with the Beck depression scale. Sleep Med. 2003;4:343-345.

113. Ross RJ, Ball WA, Dinges DF, et al. Motor dysfunction during sleep in posttraumatic stress disorder. Sleep. 1994;17:723-732.

114. Brown TM, Boudewyns PA. Periodic limb movements of sleep in combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress. 1996;9:129-136.

115. Tarasiuk A, Abdul-Hai A, Moser A, et al. Sleep disruption and objective sleepiness in children with beta-thalassemia and congenital dyserythropoietic anemia. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157:463-468.

116. Tayag-Kier CE, Keenan GF, Scalzi LV, et al. Sleep and periodic limb movement in sleep in juvenile fibromyalgia. Pediatrics. 2000;106:E70.

117. Chokroverty S. Sleep and degenerative neurologic disorders. Neurol Clin. 1996;14:807-826.

118. Askenasy JJM. Sleep disturbances in Parkinsonism. J Neural Transm. 2003;110:125-150.

119. Wetter TC, Collado-Seidel V, Pollmächer T, et al. Sleep and periodic leg movement patterns in drug-free patients with Parkinson’s disease and multiple system atrophy. Sleep. 2000;23:361-367.

120. Gadot N, Costeff H, Harel S, et al. Motor abnormalities during sleep in patients with childhood hereditary progressive dystonia, and their unaffected family members. Sleep. 1989;12:233-238.

121. Wetter TC, Brunner H, Collado-Seidel V, et al. Sleep and periodic limb movements in corticobasal degeneration. Sleep Med. 2002;3:33-36.

122. Dickel MJ, Renfrow SD, Moore PT, et al. Rapid eye movement sleep periodic leg movements in patients with spinal cord injury. Sleep. 1994;17:733-738.

123. Ferini-Strambi L, Filippi M, Martinelli V, et al. Nocturnal sleep study in multiple sclerosis: Correlations with clinical and brain magnetic resonance imaging findings. J Neurol Sci. 1994;125:194-197.

124. Nogués M, Cammarota A, Leiguarda R, et al. Periodic limb movements in syringomyelia and syringobulbia. Mov Disord. 2000;15:113-119.

125. Walters AS, Wagner M, Hening WA. Periodic limb movements as the initial manifestation of restless legs syndrome triggered by lumbosacral radiculopathy [letter]. Sleep. 1996;19:825-826.

126. Martinelli P, Pazzaglia P, Montagna P, et al. Stiff-man syndrome associated with nocturnal myoclonus and epilepsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1978;41:458-462.

127. Walker SL, Fine A, Kriger MH. L-DOPA/carbidopa for nocturnal movement disorders in uremia. Sleep. 1996;19:214-218.

128. Nikkola E, Ekblad Y, Ekholm E, et al. Sleep in multiple pregnancy: Breathing patterns, oxygenation, and periodic leg movements. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174:1622-1625.

129. Ancoli-Israel S, Kripke DF, Mason W, et al. Sleep apnea and periodic movements in an aging sample. J Gerontol. 1985;40:419-425.

130. Bastuji H, García-Larrea L. Sleep/wake abnormalities in patients with periodic leg movements during sleep: Factor analysis on data from 24-h ambulatory polygraphy. J Sleep Res. 1999;8:217-223.

131. Youngestedt SD, Kripke DF, Klauber MR, Sepulveda RS, Mason WJ. Periodic leg movements during sleep and sleep disturbances in elders. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1998;53:M391-394.

132. Mahowald MW. Assessment of periodic leg movements is not an essential component of an overnight sleep study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1340-1341.

133. Karadeniz D, Ondze B, Besset A, et al. Are periodic leg movements duiring sleep (PLMS) responsible for sleep disruption in insomnia patients? Eur J Neurol. 2000;7:331-336.

134. Chervin RD. Periodic leg movements and sleepiness in patients evaluated for sleep-disordered breathing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1454-1458.

135. Allen RP, Earley CJ. Validation of the Johns Hopkins Restless Legs Severity Scale. Sleep Med. 2001;2:239-242.

136. Garcia-Borreguero D., Larrosa O., de la Llave Y, et al. Correlation between rating scales and sleep laboratory measurements in restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2004;5(6):561-565.

137. Benz RL, Pressman MR, Hovick ET, Peterson DD. Potential novel predictors of mortality in end-stage renal disease patients with sleep disorders. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;35:1052-1060.

138. Hanly PJ, Zuberi-Khokhar N. Periodic limb movements during sleep in patients with congestive heart failure. Chest. 1996;109:1497-1502.

139. Espinar-Sierra J, Vela-Bueno A, Luque-Otero M. Periodic leg movements in sleep in essential hypertension. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1997;51:103-107.

140. Pennestri MH, Montplaisir J, Colombo R, et al. Nocturnal blood pressure changes in patients with restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 2007;68:1213-1218.

141. Atlas Task Force of the American Sleep Disorders Association. Recording and scoring leg movements. Sleep. 1993;16:748-759.

142. Iber C, Ancoli-Israel S, Chesson AL, et al. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology, and Technical specifications. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2007.

143. Ferri R, Zucconi M, Manconi M, et al. New approaches to the study of periodic leg movements during sleep in restless legs syndrome. Sleep. 2006;29:759-769.

144. Ferri R, Manconi M, Lanuzza B, et al. Age-related changes of periodic leg movements during sleep in patients with restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2007.

145. Manconi M, Ferri R, Zucconi M, et al. Time structure analysis of legs movements during sleep in REM sleep behavior disorder. Sleep. 2007;30:1779-1785.

146. Ferri R, Zucconi M, Manconi M, et al. Different periodicity and time structure of leg movements during sleep in narcolepsy/cataplexy and restless legs syndrome. Sleep. 2006;29:1587-1594.

147. Ferri R, Zucconi M, Rundo F, et al. Heart rate and spectral EEG changes accompanying periodic and non-periodic leg movements during sleep. Clin Neurophysiol. 2007;118:438-448.

148. De Lisi L. Su di un fenomeno motorio costante del sonno normale: Le mioclonie ipniche fisiologiche. Riv Pat Nerv Ment. 1932;39:481-496.

149. Vetrugno R, Plazzi G, Provini F, Liguori R, Lugaresi E, Montagna P. Excessive fragmentary hypnic myoclonus: clinical and neurophysiological findings. Sleep Med. 2002;3:73-76.

150. Oswald I. Sudden bodily jerks on falling asleep. Brain. 1959;82:92-93.

151. Brown P, Thompson PD, Rothwell JC, et al. Axial myoclonus of propriospinal origin. Brain. 1991;114:197-214.

152. Montagna P, Provini F, Plazzi G, et al. Propriospinal myoclonus upon relaxation and drowsiness: A cause of severe insomnia. Mov Disord. 1997;12:66-72.

153. Vetrugno R, Provini F, Meletti S, et al. Propriospinal myoclonus at the sleep-wake transition: A new type of parasomnia. Sleep. 2001;24:835-843.

154. Chervin RD, Consens FB, Kutluay E. Alternating leg muscle activation during sleep and arousals: A new sleep-related motor phenomenon? Mov Disord. 2003;18:551-559.

155. Broughton R. Pathological fragmentary myoclonus, intensified sleep starts and hypnagogic foot tremor: Three unusual sleep related disorders. In: Koella WP, editor. Sleep. New York: Fischer-Verlag; 1988:240-243.

156. Wichniak A, Tracik F, Geisler P, et al. Rhythmic feet movements while falling asleep. Mov Disord. 2001;16:1164-1170.

157. Butler JV, Mulkerrin EC, O’Keefe ST. Nocturnal leg cramps in older people. Postgrad Med J. 2002;78:596-598.

158. Schenck CH, Bundlie SR, Ettinger MG, et al. Chronic behavioral disorders of REM sleep: A new category of parasomnia. Sleep. 1986;9:293-308.

159. Montagna P, Sforza E, Tinuper P, et al. Paroxysmal arousals during sleep. Neurology. 1990;40:1063-1066.

160. Hening WA, Allen RP, Earley CJ, et al. An update on the dopaminergic treatment of restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder. A review by the Restless Legs Syndrome Task Force of the Standards of Practice Committee of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Sleep. 2004;27:560-583.

161. Walters AS, Hening WA, Kavey N, et al. A double-blind randomized cross-over trial of bromocriptine and placebo in restless legs syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1988;24:455-458.

162. Priano L, Albani G, Brioschi A, et al. Nocturnal anomalous movement reduction and sleep microstructure analysis in parkinsonian patients during 1-night transdermal apomorphine treatment. Neurol Sci. 2003;24:207-208.

163. Mitler MM, Browman CP, Menn SJ, et al. Nocturnal myoclonus: Treatment efficacy of clonazepam and temazepam. Sleep. 1986;9:385-392.

164. Peled R, Lavie P. Double-blind evaluation of clonazepam on periodic leg movements in sleep. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1987;50:1679-1681.

165. Laschewski F, Sanner B, Konermann M, et al. Pronounced hypersomnia in a 13-year-old patient with periodic leg movements. Pneumologie. 1997;51(suppl 3):725-728.

166. Zucconi M, Coccagna G, Petronelli R, et al. Nocturnal myoclonus in restless legs syndrome effect of carbamazepine treatment. Funct Neurol. 1989;4:263-271.

167. Staedt J, Stoppe G, Riemann H, et al. Lamotrigine in the treatment of nocturnal myoclonus (NMS): Two case reports. J Neural Transm. 1996;103:355-361.

168. Ehrenberg BL, Eisensehr I, Corbett KE, et al. Valproate for sleep consolidation in periodic limb movement disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000;20:574-578.

169. Adler CH. Treatment of restless legs syndrome with gabapentin. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1997;20:148-151.

170. Happe S, Klösch G, Saletu B, et al. Treatment of the idiopathic restless legs syndrome (RLS) with gabapentin. Neurology. 2001;57:1717-1719.

171. Mellick GA, Mellick LB. Management of restless legs syndrome with gabapentin (Neurontin®). Sleep. 1996;19:224-226.

172. Nofzinger EA, Fasiczka A, Berman S, et al. Bupropion SR reduces periodic limb movements associated with arousals from sleep in depressed patients with periodic limb movement disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61:858-862.

173. Hornyak M, Voderholzer U, Hohagen F, Berger M, Riemann D. Magnesium therapy for periodic leg movements-related insomnia and restless legs syndrome: An open pilot study. Sleep. 1998;21:501-505.

174. Kunz D, Bes F. Exogenous melatonin in periodic limb movement disorder: An open clinical trial and a hypothesis. Sleep. 2001;24:183-187.