CHAPTER 43 Perilunate Injuries of the Wrist

Perilunate injuries of the wrist include a spectrum of carpal dislocations and fracture-dislocations. These are rare injuries that often involve high-energy trauma, such as motor vehicle accidents, falls from a height, and industrial accidents. Despite the severity of trauma, initial diagnosis of these injuries tends to be delayed in 16% to 25% of cases.1 Young men are most frequently affected by these injuries. In one study1 of 166 perilunate injuries, the average age was 32 years with 97% males affected.1,2

Greater arc injuries occur when the force takes a path around the lunate of greater circumference. Greater arc injuries are perilunar fracture-dislocations of the wrist that combine ligament ruptures, bone avulsions, and carpal bone fractures in a variety of clinical forms. Greater arc perilunate fracture-dislocations most commonly involve the scaphoid, but also may include fractures of the radial and ulnar styloids, capitate, and triquetrum in any combination. Of perilunate dislocations, greater arc injuries are more common, with approximately two thirds of perilunate dislocations classified as greater arc injuries.1,3 The trans-scaphoid perilunate dislocation is the most common variant of this type of injury encountered in all published series. Of greater arc perilunate fracture-dislocations, 95% include a fracture through the middle third of the scaphoid. Usually the proximal fragment of the scaphoid remains attached to the lunate even if it has undergone a palmar dislocation; however, 3.8% of trans-scaphoid perilunate injuries may include a complete scapholunate ligament rupture.1,3–5 Fracture of the capitate also is occasionally encountered and is present in approximately 8% of all fracture-dislocations of the wrist.

Mechanism and Patterns of Injury

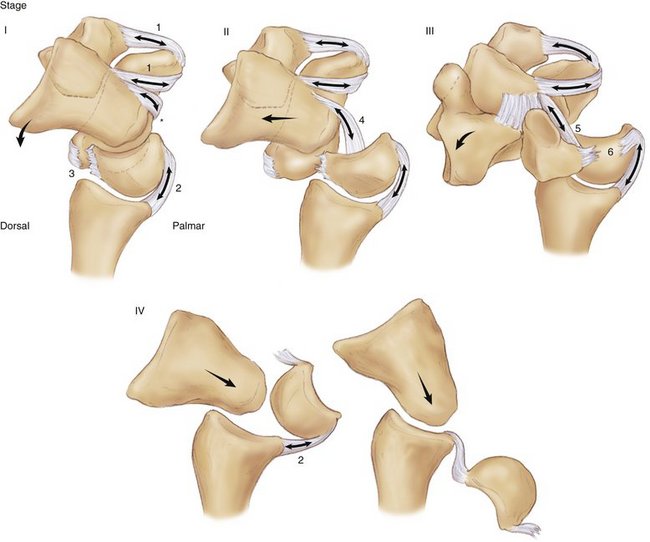

Mayfield3,6,7 described a spectrum of progressive perilunar instability that has greatly enhanced understanding of these injuries. Perilunate injuries are divided into four stages based on the concept of a sequential pattern of traumatic intercarpal wrist instability.

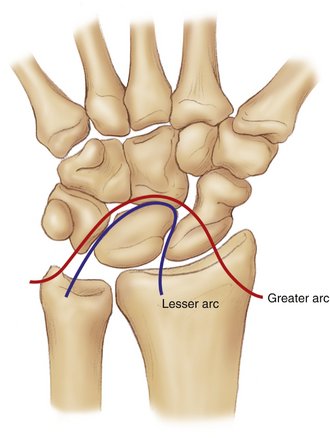

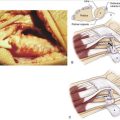

Mayfield also noted that carpal fractures may occur in perilunate injuries in lieu of ligament ruptures. In these cases, the force is concentrated on the carpus away from the lunate as it progresses from radial to ulnar, which results in the carpal bone fractures. The injuries that result are called greater arc injuries because the route of injury includes a path more remote from the lunate than lesser arc injuries (Fig. 43-1).

Progressive perilunar instability as described by Mayfield has four stages that follow a common sequence after exposure of the wrist to forceful hyperextension with a strong supination torque (Fig. 43-2). Stage I injuries result in scapholunate dissociation.6,7 Hyperextension of the scaphoid places a strong torque on the lunate and its ligaments. The extrinsic palmar and dorsal ligaments tightly stabilize the lunate, and the force is concentrated on the scapholunate ligament, which ultimately begins to tear from palmar to dorsal. If the force is strong enough, the scapholunate ligament completely ruptures, completing stage I.

In stage IV injuries, the lunate is forced volarly to dislocate into the carpal tunnel through the opened space of Poirier. Isolated volar dislocations of the lunate are the end stage of the spectrum of progressive perilunar instability. Lunate dislocations are divided into three types. Type 1 lunate dislocations result in a lunate that has rotated palmarly up to 90 degrees. Type 2 lunate dislocations produce a lunate with more than 90 degrees of palmar rotation as it is hinged on the short radiolunate ligament. Type 3 injuries result in dislocation of the lunate into the carpal tunnel. Reverse perilunar instabilities result from hyperpronation of the wrist and may be the mechanism for rare perilunate injuries with palmar dislocation of the midcarpal joint.3

In greater arc injuries, the variable pattern of fracture might include avulsion of the radial styloid or fracture of the scaphoid, capitate, triquetrum, or ulnar styloid. The most common pattern observed in greater arc injuries is the trans-scaphoid perilunate fracture-dislocation. The trans-scaphoid variant is observed in 60% of perilunate wrist injuries.1,3,6 The scaphoid fracture is through the waist in 60% to 72% of cases.1,3 The scaphoid may fracture at any level, however, including the proximal pole.

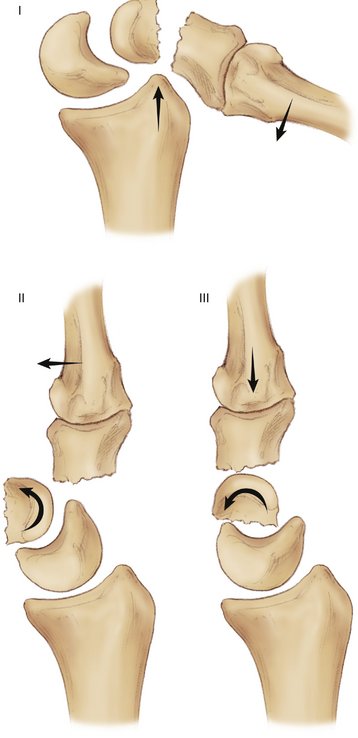

Fracture of the capitate may occur and be part of the “scaphocapitate” syndrome.3,6,8–10 This injury consists of a variation of a greater arc perilunate fracture-dislocation, in which the scaphoid and the capitate are fractured. The capitate fracture typically occurs proximally at the proximal neck of the bone. Complete rotation of the capitate fragment is typical with the proximal fragment often rotated 90 to 180 degrees. The mechanism of the fracture seems to involve a direct impact of the capitate against the dorsal lip of the radius with the wrist in a hyperextended and ulnarly deviated position. Rotation of the proximal capitate fragment is a result of the return of the distal fragment to its neutral position after dislocation (Fig. 43-3).

Presentation and Diagnosis

Patients may present with symptoms of median or ulnar nerve compression. The incidence of acute carpal tunnel syndrome manifesting with perilunate injury ranges from 16% to 46%.11 Most patients have resolution of nerve compression after closed reduction, but persistent nerve dysfunction after closed reduction may require urgent surgical decompression. Close attention should be paid to the patients’ neurovascular status, and the status of the median nerve in particular should be carefully established before and after reduction.

A standard four-view wrist series should be diagnostic of perilunate injuries and exhibit typical features. Most importantly, the dislocation of the midcarpal joint is best appreciated on the lateral view where lunocapitate dissociation can be easily visualized. The position of the lunate is best determined on the lateral view, which may reveal malrotation or dislocation of the lunate (Fig. 43-4).

FIGURE 43-4 A, The lateral injury film reveals dislocation of the midcarpal joint with dorsal dislocation of the capitate from the lunate. B, Midcarpal dislocation accompanied with palmar rotation of the lunate. C, Palmar dislocation of the lunate (Mayfield stage 4).

In perilunate injury, one also may appreciate on the anteroposterior view that there are radiographic breaks in the smooth arcs between the carpal rows described by Gilula.12 These arcs are named after Gilula, the radiologist who described the concept of the greater and lesser arc injuries. Additionally, the carpus appears foreshortened with loss of carpal height. Malrotation of the lunate produces a “triangular-shaped” lunate that overlaps the capitate on the anteroposterior radiograph (Fig. 43-5). A cortical ring sign of the scaphoid consistent with rotary subluxation of the scaphoid also may be noted on the anteroposterior radiograph. Additionally, wrist films should be inspected for associated fractures of the radial styloid, scaphoid, capitate, hamate, triquetrum, and ulnar styloid, which may represent a greater arc injury.

Sixteen percent to 25% of perilunate injuries are initially missed in the emergency department and manifest as chronic dislocations. Herzberg and colleagues1 observed that the diagnosis was missed in 41 cases of 166 greater arc injuries. Suspicion for the injury and careful interpretation of the radiographs should prevent any delay in diagnosis. Perilunate injuries tend to occur as a result of high-energy trauma, however, and patients may have more serious injuries that distract the physician from the injured wrist. Such a scenario also may contribute to a delay in the diagnosis of a perilunate injury.

Initial Treatment

In the acute trauma setting, an urgent reduction of the carpus should be performed. Closed reduction in the emergency department is the best way to restore carpal alignment initially and should be attempted. A closed reduction is usually obtainable and allows definitive surgery to be delayed to an optimal time and place.

Closed Reduction

Occasionally, closed reduction cannot be obtained because of lunate dislocation or dorsal capsular interposition.13 In irreducible cases, urgent open reduction with carpal tunnel release should be performed to relieve pressure on the median nerve and to restore carpal alignment. Another emergent indication for surgery is an open perilunate injury. Eight percent of perilunate injuries are open cases1,3 and are typically more severe. Open injuries are more likely to have a poor outcome because of a greater amount of trauma and energy absorption than closed cases. Open injuries require emergent surgical irrigation and débridement in addition to open reduction.

Acute post-traumatic carpal tunnel syndrome may occur after perilunate injury and be observed in a quarter of patients treated initially.1,14 The immediate solution is to proceed with closed reduction of the dislocated wrist in the emergency department. If median nerve symptoms persist or worsen after closed reduction of the perilunate dislocation, the surgeon should proceed with urgent decompression of the carpal tunnel to decrease the pressure caused by soft tissue swelling and hematoma formation around the median nerve.

Although gross closed reduction of perilunate injuries is possible, an absolutely anatomical reduction is difficult to obtain and hold with simple immobilization. Closed reduction and immobilization has been recommended as definitive treatment by a few authors. Most studies note that an initially acceptable closed reduction loses its alignment over time.3,15

Closed Reduction and Pinning of Perilunate Injuries

Some authors have advocated closed reduction and percutaneous pinning of perilunate injuries as definitive treatment, and satisfactory results have been reported.1,2 The overall quality of reduction and accuracy of internal fixation are greatly enhanced by an open approach. Closed reduction and pinning should be reserved for patients who refuse open reduction or have a contraindication to open surgery, such as long-term anticoagulation therapy. If after closed reduction there is residual intercarpal widening of more than 3 mm or scapholunate angle more than 80 degrees, a poor prognosis can be expected with closed treatment, and open reduction should be recommended.3

Open Reduction and Fixation of Perilunate Injuries

There is a consensus in the literature that open reduction of perilunate injuries provides the patient with the best possible prognosis.1–3,6,12,15–22 Open reduction allows the surgeon to assess fully the injury to the wrist, remove loose bone and cartilage fragments, perform direct ligament repair, and visually ensure anatomical realignment of the carpus.3,6 The clinical benefits after open reduction of perilunate injuries include a lower rate of recurrent instability and maintenance of carpal congruity. Generally, patients treated with open reduction regain better motion, strength, and pain relief than patients treated nonoperatively.

There also is agreement in the literature that prompt surgical treatment improves the prognosis over cases treated with delayed open reduction.1 Open reduction of perilunate injuries is best performed as soon as possible, but delay up to 1 week does not seem to affect the final result as long as a stable closed reduction has been obtained before surgery. Some series report satisfactory results in patients treated 6 weeks postinjury, but a significant delay to surgery can have a negative impact on the expected outcome.1,15,23

Advocates of the dorsal approach note the ability to visualize fully all pathology in perilunate dislocations and perilunate fracture-dislocations. The dorsal approach allows direct reduction and fixation of the carpal bones, interosseous ligaments, and the dorsal capsule.17,19,24 Visualization of the torn volar capsule is limited with an isolated dorsal approach, however, and the volar capsule is usually left to heal without direct repair. Sohn and associates19 argued that the volar capsule is usually automatically realigned after anatomical reduction and fixation of the carpus through a dorsal approach, and that the volar capsule heals satisfactorily during the subsequent period of immobilization without direct repair. Knoll and coworkers24 reported good results in 25 trans-scaphoid perilunate fracture-dislocations of the wrist treated with an isolated dorsal approach. Adkison and Chapman15 noted that initially in their experience they approached the wrist volarly, but found that the volar approach made it difficult to visualize the full scope of wrist pathology after a perilunate injury. These authors now favor the dorsal approach for perilunate injuries of the wrist.

Hee and colleagues23 reported on 63% good to excellent results after open reduction of trans-scaphoid perilunate injuries treated with an isolated volar approach, including internal fixation of the scaphoid. Several authors recommend combined dorsal and volar surgical incisions to manage perilunate injuries.3,6,11,16,25 Trumble and Verheyden11 reported on 22 isolated perilunate ligamentous injuries to the wrist with good results using dorsal and volar approaches. They noted that the volar approach was helpful with joint reduction and placement of internal fixation, and allowed for carpal tunnel release.

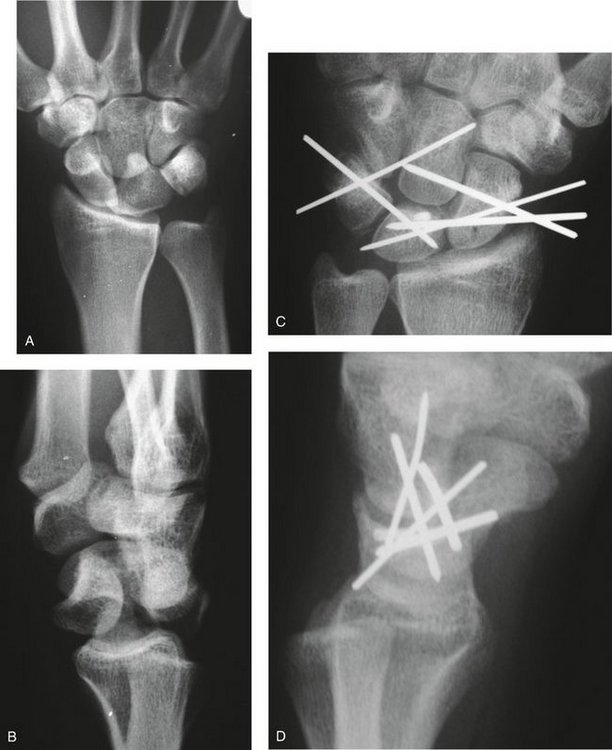

Regardless of approach, the goal of surgical treatment of perilunate injuries is to obtain a stable and accurate anatomical joint reduction. Most commonly, Kirschner wires (K-wires) are used as the principal internal fixation device of choice, but compression screws may be used for large fracture fragments. Typically, scaphoid fractures are treated with compression screws and bone grafting as needed. Intercarpal gaps are usually reduced and held together with K-wires, but the use of temporary screw fixation and cerclage wire11,14,24 to keep these gaps closed has been reported as alternative choices of internal fixation.

Authors’ Preferred Methods

Lesser Arc Injuries

The position of the lunate is reduced to its position on the radius, and if necessary, a temporary K-wire is inserted between radius and lunate to secure its position before reducing the adjacent joints. Next, the scaphoid is reduced to the lunate. A K-wire may be inserted into the scaphoid as a joystick to facilitate derotation and allow reduction of the scapholunate interval. The scaphoid is usually in a flexed orientation, and the K-wire joystick can help to rotate the scaphoid into an extended position alongside the lunate. Next, the scapholunate interval is reduced, and temporary use of bone reduction forceps may be needed to maintain alignment while inserting internal fixation. The correct alignment should result in excellent apposition of the dorsal and distalmost fibers of the scapholunate interosseous ligament. The preliminary radiograph should show no residual intercarpal gap and restoration of the scapholunate angle (30 to 60 degrees). When the position is confirmed to be acceptable, the scapholunate interval is stabilized with two 0.062-inch K-wires inserted from the scaphoid into the lunate. An additional 0.062-inch K-wire is inserted from the distal scaphoid into the capitate to prevent rotary subluxation of the scaphoid and subsequent loss of reduction (Fig. 43-6).

Greater Arc Injuries

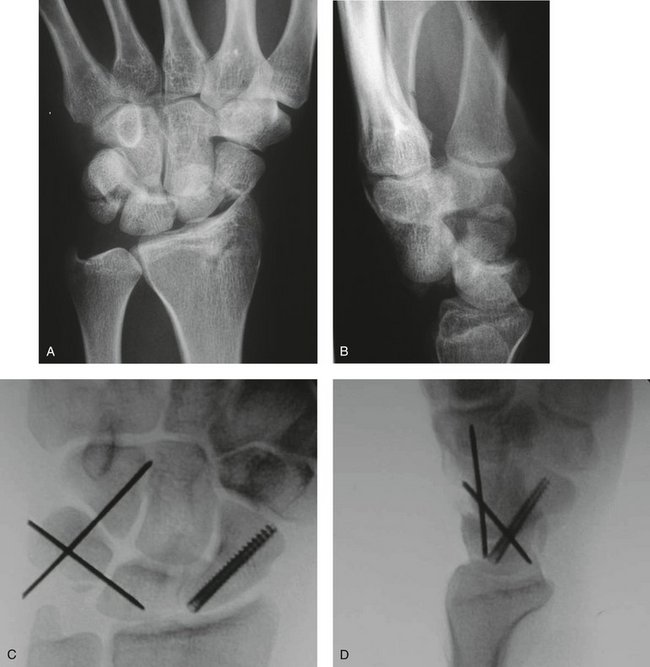

The scaphoid typically is repaired with a headless self-compressing screw if possible. The screw is inserted into the scaphoid fracture antegrade through the proximal pole; excellent fixation is typical (Fig. 43-7). The scaphoid fracture may be comminuted or very proximal, however, making it difficult to obtain solid fixation. K-wire fixation is acceptable in these situations, and bone grafting from the distal radius should be obtained if necessary.

Occasionally, the proximal pole of the scaphoid is a free fragment with simultaneous rupture of the scapholunate ligament. Herzberg and colleagues1 reported that simultaneous scaphoid fracture and scapholunate ligament tear occurred in 3.8% of cases. In these situations, it is probably best to use K-wire fixation for the scaphoid fracture because the presence of a screw in the scaphoid makes scapholunate ligament repair more difficult. After wire fixation of the scaphoid, the scapholunate joint is reduced and stabilized as noted in the technique for lesser arc perilunate repair.

When the capitate is fractured, the open reduction typically proceeds with this bone first (Fig. 43-8). The head of the capitate is typically a free osteocartilaginous fragment that has rotated 180 degrees. The fragment can be derotated and repaired with a headless compression screw or with K-wire fixation. Bone grafting from the distal radius may be required. Fractures of the radial or ulnar styloids are usually avulsion fractures that are treated with direct open reduction and pin fixation, although screw fixation also may be considered if the fragments are large.

FIGURE 43-8 A to D, Greater arc perilunate injury with scaphoid and capitate fractures (scaphocapitate syndrome). Note the fracture of the capitate and the malrotation of the fragment. Open reduction and internal fixation is performed through a dorsal approach with headless cannulated screw fixation of the scaphoid and capitate. The lunotriquetral joint is stabilized with Kirschner wires after open reduction.

Finally, the lunotriquetral joint is reduced and stabilized. In perilunate fracture-dislocation, the lunotriquetral ligament is usually disrupted without fracture, and the lunotriquetral joint is reduced and pinned with 0.062-inch K-wires as noted in the technique of lesser arc perilunate repair. Fracture of the triquetrum may occur in greater arc injury, however. In such cases, the triquetral fracture can be treated with pin or screw fixation depending on the size of the fracture fragments.

Postoperative Care

Pins are cut below the skin, and the wrist is immobilized initially in a short arm splint and bulky hand dressings until suture removal. A short arm cast is used until 10 weeks postoperatively, at which time the pins are removed. Careful surveillance of the scaphoid fracture is required because of the possibility of delayed union or nonunion. The patient is enrolled in an occupational therapy program after cast removal with gradual progression of activities. Twelve to 18 months may be required until the final result is obtained, when pain resolves, and motion and strength have been optimized.25

Outcomes

Patients who undergo timely ORIF for perilunate injuries have the most successful outcomes. Most authors agree that the expected recovery of wrist range of motion after ORIF is about a 110-degree arc of flexion and extension with return of approximately 75% of grip strength.3 Although outcome studies of perilunate injuries have shown suboptimal assessment scores consistent with loss of function,25,26 there also are numerous reports of acceptable patient satisfaction with regards to pain relief and function after ORIF. Hee and colleagues23 reported 62% excellent and good results in the outcome of 15 patients treated with ORIF. Sotereanos and associates25 noted that despite loss of motion and grip, 82% of patients were satisfied with the procedure, but only 45% returned to work. Other series report a much more optimistic prognosis for return to work after perilunate ORIF, including a return to employment rate of 80% to 100% with 66% to 92% able to return to their preinjury occupation.11,19,24,26

Souer and coworkers14 compared K-wires with temporary intercarpal screws in 18 patients (9 treated with 3-mm cannulated intercarpal screws and early mobilization at 3 weeks, and 9 treated with intercarpal K-wires and casting for 3 months). The intercarpal screws were removed an average of 5 months and the K-wires an average of 3 months after the initial procedure. Four patients (two in each cohort) had wrist arthrodesis with poor results. Among the 14 remaining patients, the final flexion arc was 97 degrees for patients treated with screw fixation compared with 73 degrees for patients treated with K-wires. The authors concluded that the results of treatment with temporary screws were comparable to the results of treatment with temporary K-wires. The appeal of temporary screw fixation lies in the ability to begin mobilizing the wrist within a few weeks and the absence of pin-related complications. Although superior wrist motion was obtained in the intercarpal screw group, the numbers were too small to provide any definitive conclusions.14

Delay to definitive surgical treatment is one of the most significant variables that adversely affect the outcome of perilunate injuries. This is significant because there is frequently a delay in the diagnosis and treatment of perilunate injuries, which may result in a poor outcome. Herzberg and colleagues1 noted that patients treated with ORIF within 1 week had superior Mayo wrist scores compared with patients treated later, with only fair to poor results reported in patients treated after 45 days. Open injuries also are likely to have a poor outcome. The adverse results after open perilunate injuries is probably a reflection1 of the more serious initial injury to the wrist, including the greater magnitude of injury to joint surfaces and ligaments.

Poor results in most series have followed cases with residual wrist instability, ulnar translocation of the carpus, and scaphoid nonunion. Despite the serious injury to the wrist in the vicinity of the lunate, reported cases of Kienböck’s disease and lunate fragmentation are rare after perilunate wrist injury. The reported incidence of post-traumatic arthrosis at late follow-up is high, however, and is usually identified in the midcarpal joint. The incidence of post-traumatic arthritis after treatment of perilunate injuries is reported to range from 50% to 100% in the literature.1,14,16,26

Late Presentation

Too many perilunate injuries are missed at initial presentation, and this creates a very difficult situation for the treating surgeon. Suboptimal results can be expected in these cases, but open reduction should be performed if possible. It is unknown how late in presentation that ORIF can be performed, but there are reports3 of successful open reduction performed up to 35 weeks postinjury. Some authors have recommended the use of preoperative or intraoperative traction with external fixation to facilitate delayed open reduction.3

Siegert and colleagues27 and others evaluated 16 perilunate dislocations and fracture-dislocations with an average delay to surgery of 17 weeks. Despite the delay in presentation, they were able to perform open reduction in six of these cases with acceptable outcomes. When open reduction was impossible, the authors resorted to lunate excision, proximal row carpectomy, or wrist arthrodesis as primary treatment. Siegert and colleagues27 noted that patients treated with simple lunate excision had poor results, and this was not recommended as primary treatment of chronic perilunate injuries.

1 Herzberg G, Comtet JJ, Amadio PC, et al. Perilunate dislocations and fracture dislocations: a multicenter study. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1993;18:768-779.

2 Herzberg G, Forissier D. Acute dorsal trans-scaphoid perilunate fracture-dislocations: medium term results. J Hand Surg [Br]. 2002;27:498-502.

3 Garcia-Elias M, Geissler WB. Carpal instability. In Green DP, Hotchkiss RN, Pederson WC, et al, editors: Green’s Operative Hand Surgery, 5th ed, Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone, 2005.

4 Berger RA. The ligaments of the wrist: a current overview of anatomy with considerations of their potential functions. Hand Clin. 1997;13:63-82.

5 Berger RA. The anatomy of the ligaments of the wrist and distal radioulnar joints. Clin Orthop. 2001;383:32-40.

6 Grabow RJ, Catalano L. Carpal dislocations. Hand Clin. 2006;22:485-500.

7 Mayfield JK, Johnson RP, Kilcoyne RF. Carpal dislocations: pathomechanics and progressive perilunar instability. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1980;5:226-241.

8 Sawant M, Miller J, Heath T. Scaphocapitate syndrome in an adolescent. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2000;25:1096-1099.

9 Vance RM, Gelberman RH, Evans EF. Scaphocapitate fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62:271-276.

10 Weseley MS, Barenfeld PA. Transscaphoid, transcapitate, transtriquetral perilunate fracture dislocation of the wrist: a case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;54:1073-1078.

11 Trumble T, Verheyden J. Treatment of isolated perilunate and lunate dislocations with combined dorsal and volar approach and intraosseous cerclage wire. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2004;29:412-417.

12 Taleisnik J. The Wrist. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1985.

13 Jasmine MS, Packer JW, Edwards GS. Irreducible trans-scaphoid perilunate dislocation. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1988;13:212-216.

14 Souer JS, Rutgers M, Andermahr J, et al. Perilunate fracture-dislocations of the wrist: Comparison of temporary screw versus K-wire fixation. J Hand Surg. 2007;32:318-325.

15 Adkison JW, Chapman MW. Treatment of acute lunate and perilunate dislocations. J Bone Joint Surg. 1982;164:199-207.

16 Cooney WP, Bussey R, Dobyns JH, et al. Difficult wrist fractures. Clin Orthop. 1987;214:136-147.

17 Moneim MS. Management of greater arc carpal fractures. Hand Clin. 1988;4:457-467.

18 Moneim MS, Hofmann KE, Omer GE. Transscaphoid perilunate fracture-dislocation: result of open reduction and pin fixation. Clin Orthop. 1984;190:227-235.

19. Sohn R, Rafijah G, Jo M, et al: Dorsal only approach for trans-scaphoid perilunate fracture dislocation: a review of results. Poster presented at 60th Annual Meeting of American Society of Surgery of the Hand, San Antonio, Texas, 2006.

20 Soejima O, Iida H, Naito M. Transscaphoid-transtriquetral perilunate fracture dislocation: report of a case and review of the literature. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2003;123(6):305-307.

21 Green DP, O’Brien ET. Open reduction of carpal dislocations: indications and operative techniques. J Hand Surg. 1978;3:250-265.

22 Green DP, O’Brien ET. Classification and management of carpal dislocations. Clin Orthop. 1980;149:55-72.

23 Hee HT, Wong HP, Low YP. Transscaphoid perilunate fracture/dislocations—results of surgical treatment. Ann Acad Med (Singapore). 1999;28:791-794.

24 Knoll VD, Allan C, Trumble TE. Trans-scaphoid fracture dislocations: results of screw fixation of the scaphoid and lunotriquetral repair with a dorsal approach. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2005;30:1145-1152.

25 Sotereanos DG, Mitsionis GJ, Giannakopoulos PN, et al. Perilunate dislocation and fracture dislocation: a critical analysis of the volar-dorsal approach. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1997;22:49-56.

26 Hildebrand KA, Ross DC, Patterson SD, et al. Dorsal perilunate dislocations and fracture-dislocations: questionnaire, clinical, and radiographic evaluation. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2000;25:1069-1079.

27 Siegert JJ, Frassica FJ, Amadio PC. Treatment of chronic perilunate dislocations. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1988;13:206-212.