CHAPTER 68 Pericardial Effusion

Pericardial effusion can occur from various causes, including infection, trauma, and systemic disease. Infectious causes of pericardial effusion are described in more detail in Chapter 69. This chapter focuses on pericardial effusion secondary to systemic disease.

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Pericardial effusion is an abnormal accumulation of fluid within the pericardial space. In the absence of acute inflammation, clinical symptoms depend on the size of the effusion, the rate of accumulation, and the ability of the pericardium to expand. Cardiac tamponade occurs when the intrapericardial pressure is high enough to impede cardiac filling. The pericardial fluid may be a transudate, an exudate, or hemorrhagic. Pericardial effusion is common in some diseases, such as chronic renal disease and heart failure. Pericardial effusion can occur in any collagen vascular disease, but is particularly common in patients with lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis (Fig. 68-1).

MANIFESTATIONS OF DISEASE

Clinical Presentation

Pericardial effusion in the absence of acute pericarditis may be clinically silent, unless tamponade physiology is present. The clinical symptoms of cardiac tamponade are related to the resulting decrease in cardiac output and include hypotension and tachycardia. Jugular venous distention is present on physical examination. A decrease in systemic blood pressure by more than 10 mm Hg during inspiration is diagnostic of pulsus paradoxus. Pulsus paradoxus was originally described as the disappearance of the radial pulse during inspiration. Pulsus paradoxus is actually an exaggeration of the normal decrease in systemic blood pressure during inspiration.1

Imaging Techniques and Findings

Radiography

Chest radiographs may show interval enlargement of the cardiac silhouette. Pericardial effusion should be suspected when cardiac enlargement occurs over a short period of time (Fig. 68-2). The classic “water flask” appearance of the cardiac silhouette in pericardial effusion can also be seen in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. In patients with dilated cardiomyopathy, the hilar structures are displaced laterally as the heart enlarges. In patients with large pericardial effusion, the hila may become obscured because the pericardial reflections extend to cover the proximal portions of the great vessels.2 If there is sufficient subepicardial fat, and the fat is oriented such that it is visible on radiographs, widening of the pericardial line, indicative of pericardial effusion, can be detected on chest radiograph—the epicardial fat pad sign (see Fig. 68-2).3,4

Ultrasonography

On echocardiography, uncomplicated pericardial fluid is hypoechoic and is found diffusely throughout the pericardial space. The size of the effusion is quantified as small when the space between the visceral and parietal pericardium measures less than 5 mm, moderate when the space measures between 5 mm and 2 cm, and large when the space measures more than 2 cm.5 Loculated fluid and intrapericardial stranding may be present. Echocardiographic findings of pericardial tamponade in the presence of a pericardial effusion include collapse of the right atrium during systole lasting more than a third of the systolic interval, collapse of the right ventricular free wall during diastole, and abnormal septal motion toward the left ventricle.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Presentation

Pericardial effusion may be clinically silent. In the setting of cardiac tamponade, other causes of hypotension, shock, and elevated jugular venous distention, such as heart failure, pulmonary embolism, and myocardial infarction of the right ventricle, should also be considered.6

1 Spodick DH. Pulsus paradoxus. In: Spodick DH, editor. The Pericardium. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1997:191-199.

2 Baron MG. Pericardial effusion. Circulation. 1971;44:294-299.

3 Lane EJ, Carsky EW. Epicardial fat: lateral plain film analysis in normals and in pericardial effusion. Radiology. 1968;91:1-5.

4 Carsky EW, Mauceri RA, Azimi F. The epicardial fat pad sign. Radiology. 1980;137:303-308.

5 Otto CM. Pericardial disease: two-dimensional echocardiographic and Doppler findings. In: Otto CM, editor. Textbook of Clinical Echocardiography. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000:213-228.

6 LeWinter MM, Kabbani S. Pericardial diseases. In: Zipes DP, Libby P, Bonow RO, et al, editors. Braunwald’s Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2005:1757-1780.

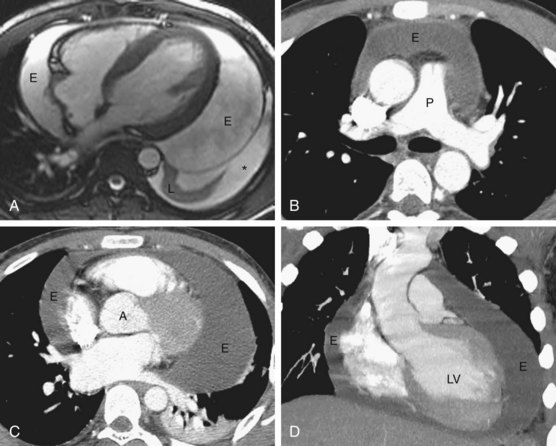

FIGURE 68-1

FIGURE 68-1

FIGURE 68-2

FIGURE 68-2