Chapter 17 Percutaneous Spinal Biopsy

INTRODUCTION

Open biopsies are considered the gold standard for obtaining diagnostic tissue from spinal lesions. The accuracy rate of open biopsies has been shown to be as high as 98%. In contrast, a percutaneous needle biopsy has been reported to range between 59% and 93% in accuracy in a different series.1 The advantage of taking the percutaneous biopsy route over an open biopsy in deep-seated lesions at cervical, thoracic, and lumbar vertebral levels is well-established: it is safe, cost-effective, and less painful. A percutaneous biopsy is preferred for lesions that have a soft tissue component or are located close to vital structures, under fluoroscopic or computed tomography (CT) guidance.

APPROACH ROUTES

TRANSPEDICULAR APPROACH

The transpedicular route combines the least invasive biopsy method with conventional x-rays or CTs taken for the correct diagnosis of thoracic and lumbar lesions. This route avoids neural and vascular injury as long as the needle is intrapedicularly located (Fig. 17-1). This procedure can be performed with only anteroposterior (AP) and lateral views of the thoracic and lumbar spine. The transpedicular approach can be applied to simultaneous vertebroplasty.2 At cervical regions, CT guidance is required to perform a transpedicular biopsy.

PARASPINAL APPROACH

A transcostotransversal route can be used for thoracic vertebrae lesions. It is directed between the thoracic pedicle and rib head (Fig. 17-2). The posterolateral paraspinal route is applied to upper lumbar lesions.

TECHNIQUES

TRANSPEDICULAR APPROACH WITH FLUOROSCOPIC GUIDANCE3

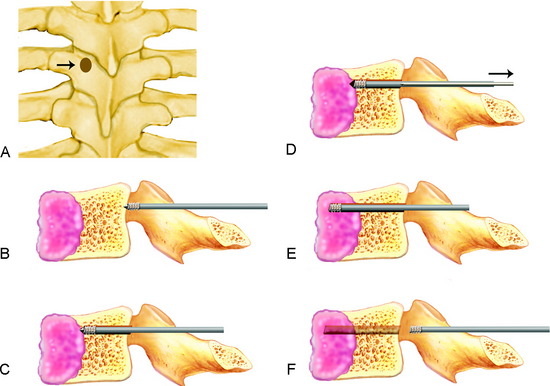

Using this approach, the patient is placed in the prone position with a suitable supporter under the abdomen. Under local anesthesia with 0.5% lidocaine (Xylocaine) administered to the marked skin area, the paravertebral muscles, and the articular process of the vertebra, a threaded bone biopsy trocar (Osty-Cut, Angiomed, Karlsruhe, Germany) with an outer diameter of 2 mm is introduced through the point marked on the skin. It is then advanced to the dorsal cortex of the lamina just dorsal and lateral to the pedicle, and then into the pedicle by screwing in the trocar under guidance by observation of AP and lateral x-ray imaging. Special care is taken not to perforate the medial cortex of the pedicle to prevent injury to the nerve root or spinal cord (Figs. 17-3, A and B). It is important that the Steinmann pin be inserted into the bull’s eye of the pedicle so that complications brought about by violating the confinement of the pedicle can be avoided. To keep healthy hard bone tissue from entering the biopsy needle and clogging the lumen, which will prevent the surgeon from obtaining soft tumor tissue, the obturator should not be withdrawn until the biopsy needle has passed through the pedicle and has reached the posterior surface of the tumor mass (Fig. 17-3, C). After the trocar has advanced sufficiently, the needle is withdrawn (Fig. 17-3, D). The needle is advanced into the tumor mass and rotated. The trocar is then connected to an aspiration kit, and tissue or fluid is collected into the lumen of the trocar by aspiration at low negative pressure (Fig. 17-3, E). After a sufficient amount of tissue is obtained, the trocar is removed (Fig. 17-3, F). The collected tissue pieces are fixed in 4% buffered formalin for pathological examination.

COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY-GUIDED BIOPSY

The reported accuracy of CT-guided spinal bone biopsy is 67–97%. The complication rate ranges from 0–26%.4 Lytic lesions, mixed lesions of lytic and sclerotic mass, and compression fractures have the highest diagnostic rate of more than 90%. Sclerotic lesions have statistically lower accuracies of less than 80%.5 Typically, large core samples from needles on the order of 15 gauge or less can easily be obtained from a sclerotic lesion. Overall, the procedure is the same with a fluoroscopic biopsy. One of the drawbacks of CT guidance is that continuous monitoring is not possible. For the enhanced diagnostic yield, targeting is very important. The boundary of the lesion should be drawn from the T2-weighted magnetic resonance image (MRI). A high-intensity signal within the medulla vertebrae on T2-weighted fast spin echo MRI sequence has been shown to be associated with healing insufficiency fractures (traumatic or osteopenic), malignancy, or infection. Therefore, the biopsy of a hyperintense T2-weighted fast spin echo lesion is recommended if the diagnosis is in doubt, even if the absence of bone trabecular destruction or vertebral collapse is indicated.

BIOPSY THROUGH INTACT BONE

For the osteolytic lesions covered by intact bone, an intact-bone transgressing technique is useful, in which a simple, inexpensive, and small-caliber (18-gauge) instrument is used to allow multiple passage of 20-gauge biopsy guns for effective tissue sampling.6

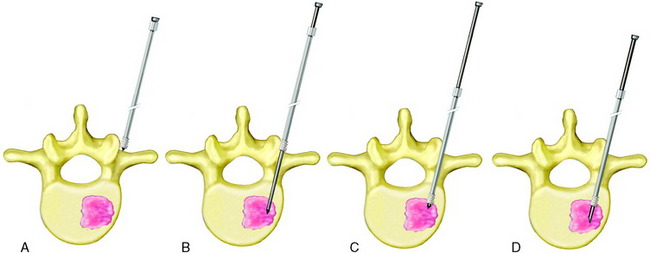

The lesion area is accessed via a posterior or posterolateral route, with the patient lying prone. An 11-cm long, 18-gauge disposable trocar needle consisting of a diamond-tipped trocar and a thin-walled cannula is inserted onto the vertebra (Fig. 17-4, A). The 11-cm long trocar is then substituted with a 15-cm trocar of the same gauge. With a rotating advancement at the hub the trocar is driven through the bone cortex and cancellous bone into the lesion (Fig. 17-4, B), while the cannula is kept still by holding the hub firmly with the other hand. After checking with CT that the tip of the trocar is just within the lesion, it is kept still by holding the hub firmly with the hand resting on the patient’s back, while the cannula is driven into the lesion with rotating advancement at the hub (Fig. 17-4, C). The distance of advancement through intact bone from the vertebral surface to the lesion is the same for both trocar and cannula. It is measured on the CT image and estimated from the distance between the skin’s surface and the needle hub. After checking with CT that the tip of the cannula is just within the lesion, the trocar is removed and a 15-cm long, 20-gauge automate side-cutting biopsy needle is passed through the cannula to obtain four to eight biopsies, with the sampling notch of the needle rotated to a slightly different direction for each biopsy (Fig. 17-4, D).

TYPES OF NEEDLES

PROBLEMS ASSOCIATED WITH NEEDLE BIOPSIES

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS IN SACRAL LESIONS

The diagnostic value of open and needle biopsies in the sacrococcygeal region is somewhat different from the cervical and thoracolumbar spine because of anatomical and oncological factors.7 Anatomically, the sacrum is more surgically accessible, and in the lower sacrum, the neural elements do not exist as in the spinal column. The sacrum is larger and has a broad posterior surface along the sacral ala. Sacral tumors usually are quite large on presentation, and most of them are located or have extension into the posterior bone or soft tissue structures, which makes for an easy surgical approach. Therefore, open biopsies of the sacrum are technically easier than in other portions of the spine. Biologically, the majority of spinal metastases tend to occur in the thoracolumbar region. However, in the sacrum, primary tumors such as chordoma predominate. Therefore, the likelihood of encountering a primary bone tumor in the sacral region appears to be greater than in other spinal locations. The diagnostic value of needle biopsy for primary bone tumors is less than for metastatic lesions. For a correct diagnosis, open biopsy is favored over needle biopsy in the sacral region. Fine needle aspirations performed in primary bone tumors are apt to result in false negative data.

CASE ILLUSTRATION

A 45-year-old female patient presented with posterior neck pain with right arm pain.

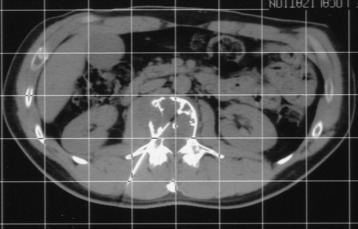

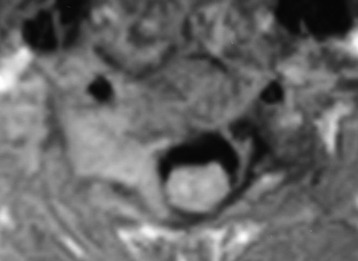

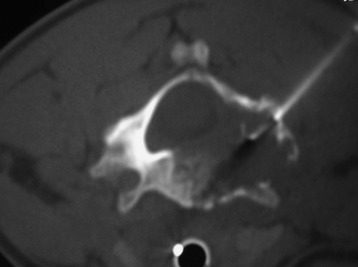

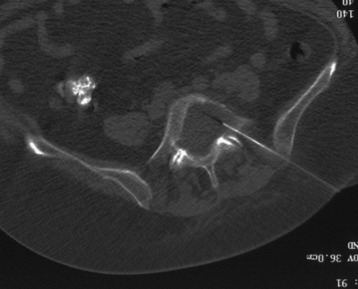

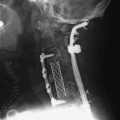

On MRI, a C5 vertebral body mass was detected. The mass extended to the right neural foramen and right vertebral artery (Fig. 17-5). The percutaneous biopsy was performed with CT guidance. The patient was placed in the prone position, and the needle was advanced through the right C5 pedicle into the C5 vertebral body (Fig. 17-6). A Jamshidi needle (8-gauge) was used. The obtained specimen was sufficient for a correct diagnosis. The result was multiple myeloma.

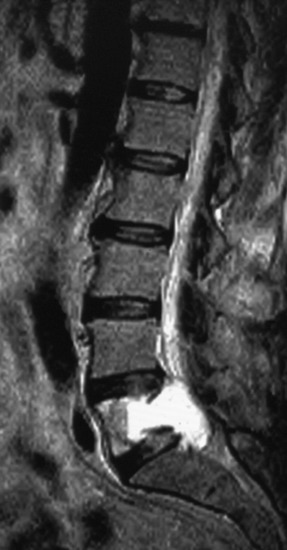

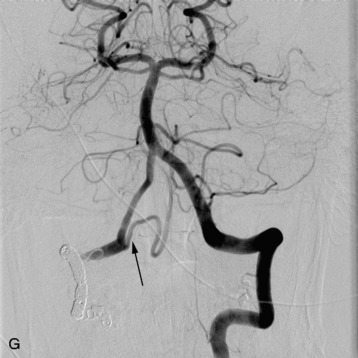

A 54-year-old man had suffered from low back pain and left leg paresthesia for 6 months. An MRI scan showed the destructive lesion at the L5 vertebral body (Fig. 17-7). The mass was growing out of the posterior cortex and invading the spinal canal. Needle biopsy was attempted through the affected pedicle (Fig. 17-8). The amount of specimen was sufficient to derive a correct diagnosis. The pathological diagnosis was metastatic adenocarcinoma.