CHAPTER 172 Percutaneous Cordotomy and Trigeminal Tractotomy-Nucleotomy

History

The first discoveries of the anatomy and function of the spinal cord in clinical and experimental studies were accomplished by Galen in the 2nd century AD.1,2 Further clinical suggestions about the function of the spinal cord emerged from empirical observations. In 1871, Müller reported a patient in whom isolated analgesia was observed after lesioning of the spinal cord.3 A few years later, Gowers reported a case of localized injury to the anterolateral column at the level of the third cervical segment that resulted in complete analgesia with preservation of tactile sensation on the opposite half of the body. Gowers concluded that the afferent pathway for pain was located in the anterolateral column.3 The spinothalamic tract was first identified by Edinger in 1889 while conducting experiments on amphibians and newborn cats. In 1905, Spiller reported that pain and temperature sensation ascends in the anterolateral spinal cord based on autopsy findings in patients with tuberculoma at the thoracic level of the spinal cord.4 Schüller sectioned the anterolateral tract in monkeys in 1910 and termed the procedure chordotomie.5 The first cordotomy in a human was carried out by Martin at Spiller’s instigation, and numerous technical difficulties were encountered.6 In 1920, Frazier published a series of six patients who underwent cordotomy, five of whom experienced postoperative pain relief.7 After this publication, cordotomy was accepted as an important type of intractable pain–relieving procedure. Since its first description, open cordotomy has usually been performed via the posterior approach. The anterior approach was described by Collis and Cloward but has not been widely used because of inherent technical difficulties.8,9

Denervation of the craniofacial region by sectioning of a special pain-conducting pathway was first described by Olof Sjöqvist in 1938.3 He sectioned the tractus at the inferior olive level in an open technique via craniectomy in the posterior fossa. In 1942, White and Sweet observed hypoalgesia after trigeminal tractotomy in the innervation area of the 7th, 9th, and 10th cranial nerves.10 Sweet then used this procedure for the treatment of glossopharyngeal neuralgia. Kunc performed selective tractotomy 12 mm above the second cervical root level, which successfully relieved glossopharyngeal neuralgia.11

Cordotomy and tractotomy are performed mostly in (cancer) patients with poor health status who cannot tolerate open surgery. Clinicians have labored for years to develop noninvasive treatments in an effort to accommodate this patient subgroup. Percutaneous cordotomy and tractotomy are relatively new treatment modalities performed with a needle electrode system and, conventionally, radiographic guidance. Cordotomy was first described and performed by Mullan and colleagues in 1963 with a radioactively tipped strontium needle.12 Because of undesirable effects of the radioactive source, Mullan and coworkers began making unipolar, anodal electrolytic lesions in 1965.13 In the same year, Rosomoff and associates described the technique of percutaneous cordotomy with a radiofrequency (RF) electrode system, which facilitated making a small, discrete lesion in the pain-conducting system of the spinal cord.14 With the help of impedance measurements and stimulation, evaluation of the target’s neurophysiologic function became possible. The percutaneous method was performed in the lower cervical region via an anterior approach by Lin and coworkers in 1966.15

In 1967 and 1968, Crue and colleagues and Hitchcock independently developed a percutaneous technique using RF thermocoagulation and performed the first stereotactic trigeminal tractotomies.16,17 Trigeminal tractotomy was used for the treatment of postherpetic facial pain in 1972 by Hitchcock and Schvarcz.18 Schvarcz also used the same procedure to create lesions primarily in the second-order neurons at the oral pole of the nucleus caudalis at the level of the occipitocervical junction19 and termed this procedure trigeminal nucleotomy.20

Radiography, the conventional visualization system in stereotactic pain procedures, cannot demonstrate a patient’s spinal cord morphology. In 1988, Kanpolat and coauthors published the first experience with computed tomographic (CT) visualization in a stereotactic pain procedure and later used CT guidance as a visualization method for percutaneous cordotomy.21,22 CT visualization offers the advantage of topographic orientation. Using this contribution, Kanpolat and colleagues described selective unilateral and bilateral cordotomy and trigeminal tractotomy in the following years.23,24 Morphologic orientation and neurophysiologic evaluation of the target allowed the use of this truly stereotactic method with RF energy. CT-guided application of trigeminal tractotomy was described and published in 1989.25 These procedures define the concept of CT-guided destructive procedures in classic percutaneous pain surgery.

Anatomy of the Targets and Their Environs

Computed Tomography–Guided Percutaneous Cordotomy

Morphometric studies of the spinal cord at the level of the surgical approach (C1-2) provide the most critical information pertaining to anatomic orientation for cordotomy. At the C1-2 level, the diameters of the spinal cord were reported by Mullan as being 10 mm anteroposteriorly (AP) and 13 mm transversely (T).26 We measured the spinal cord diameters of 63 patients who underwent CT-guided percutaneous cordotomy at the C1-2 level as being 7.0 to 11.4 mm (AP) (mean, 8.66 ± 0.72 mm) and 9.0 to 14.0 mm (T) (mean, 10.9 ± 1.56 mm).27 Kameyama and associates found spinal cord diameters at the C2 level to be 6.4 ± 0.4 mm (AP) and 10.5 ± 0.8 mm (T). These values were 6.0 ± 0.4 mm (AP) and 12.2 ± 0.8 mm (T) and 5.5 ± 0.5 mm (AP) and 10.6 ± 0.7 mm (T) at the C5 and T1 levels, respectively.28 In contrast, Poletti found the transverse diameter of the spinal cord of a cancer patient at the T2 level to be 5.2 mm.29

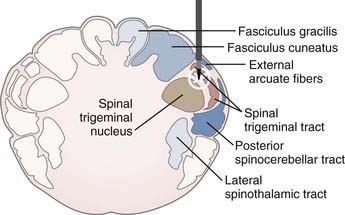

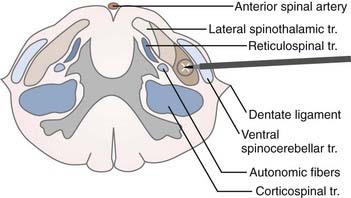

The target in cordotomy is the lateral spinothalamic tract, which is located in the anterolateral part of the spinal cord (Fig. 172-1).10,30–32 This ascending tract primarily carries information about pain and temperature and relays some tactile information. The distribution of the pain-conducting fibers within the anterolateral spinal tract is such that the small, ventrally located fibers generally conduct pain sensation. The organization of fibers from the outside inward is superficial pain, temperature, and deep pain.33 Because most of the fibers in the anterolateral system decussate over two to five segments before entering the anterolateral columns, spinothalamic cordotomy aims to interrupt the spinothalamic tract ascending contralaterally to the painful side. Although the majority of pain-transmitting fibers decussate normally, the rate and position of decussated axons may vary considerably among individuals; thus, unilateral cordotomy can, on rare occasion, produce ipsilateral analgesia in some individuals because of nondecussated neurons.10

FIGURE 172-1 Schematic representation of the target (lateral spinothalamic tract) and its environs at the C1-2 level.

The anterolateral sensory system has a somatotopic relationship, with fibers from higher levels laminating medially and ventrally and fibers from lower levels laminating laterally and dorsally within the lateral spinothalamic tract.30,31,33 In 1926, Peet stated that deeper cordotomy incisions, particularly in the anterior portion of the anterolateral tract, cause analgesia in the upper parts of the body.32 In 1939, Hyndman and Van Epps suggested the possibility of producing high-level analgesia with preservation of pain and temperature sensibility in the lower half of the body.30 Segmentation of the fibers provides the opportunity for selective cordotomy, given that anteromedial lesions denervate the contralateral arm and upper chest region whereas posterolateral lesions denervate the sacral and lumbar area (Fig. 172-1).

The pyramidal tract is usually located posterior to the dentate ligament. It must be remembered, however, that in rare instances the dentate ligament is posterior to its normal location.10 Moreover, there is considerable variation in the size and location of the ventral corticospinal tract; for instance, it sometimes fails to decussate at all. Because motor decussation may extend from the obex to the C1 level, contralateral leg weakness may also occur if the lesion is too high.33 The ventral spinocerebellar tract is located in the lateral part of the lateral spinothalamic tract. Lesions of this tract cause ipsilateral ataxia of the arm. Autonomic fibers related to bowel and bladder function are found in the lateral part of the lateral horn of the gray matter. Immediately posterior to the autonomic fibers are vasomotor fibers, bilateral lesioning of which causes hypotension.33

The most important region related to the practice of upper cervical cordotomy is the medial aspect of the lateral spinothalamic tract, where the descending respiratory pathway is located. Nathan emphasized the importance of this region as follows: “The descending respiratory pathway may be considered to be the most important tract of the spinal cord; yet its position in man is unknown. It is important to work out the location of these descending fibers not only to complete anatomic knowledge but also to provide those practicing surgery on the cervical cord with essential information. The absence of this knowledge contributed to the death of some of our patients after cordotomy and this has also been a cause of death in patients from other series of cordotomies.”34 Belmusto and colleagues concluded that fibers associated with respiration in humans occupy an area from C1 to C3, 3.0 to 5.5 mm from the lateral margin of the cord.35 Hitchcock and Leece suggested that the anterior portion of the respiratory tract is largely related to diaphragmatic function whereas the posterior portion supplies the remainder of the respiratory musculature—namely, the intercostal muscles, as well as the abdominal and lumbar musculature used in respiration.36

Computed Tomography–Guided Percutaneous Trigeminal Tractotomy-Nucleotomy

CT-guided percutaneous trigeminal tractotomy-nucleotomy (TR-NC) is performed at the occiput-C1 level. Upper spinal cord diameters at this level were measured in 30 patients. Anteroposterior measurements were 7.0 to 12.8 (mean, 9.13 ± 0.83), and transverse diameters were 9.3 to 14.0 mm (mean, 11.6 ± 0.76).27

Trigeminal afferent fibers, which carry the sensations of pain and temperature, enter the pons and send a caudal branch (the descending trigeminal tractus) into the medulla. The descending trigeminal tractus overlies the spinal trigeminal nucleus in the posterolateral part of the spinal cord at the cervicomedullary junction. Primary sensory fibers from the 7th, 9th, and 10th cranial nerves also enter the descending tractus of the trigeminal nerve.37,38 The three divisions of the trigeminal nerve have a special topographic organization in the descending tractus of the nerve. Fibers from the 7th, 9th, and 10th cranial nerves lie slightly medially behind the tractus; trigeminal afferents that carry the sensations of pain and temperature, unlike other sensory modalities, descend in the spinal trigeminal tractus and enter the nucleus.39 The spinal trigeminal nucleus has three distinct subdivisions along its pontospinal extent: (1) the nucleus oralis, located rostrally between the pons and medulla; (2) the nucleus interpolaris, located interomedially; and (3) the nucleus caudalis, located at the medullospinal junction and extending down to the C2 segment level. The nucleus caudalis represents the substantia gelatinosa, and there is extensive overlap between the facial and high cervical afferents, where the 7th, 9th, and 10th cranial nerve afferents also end. Destruction of the oral pole of the nucleus caudalis plays a special role in pain relief.40

There is a topographic representation of the ipsilateral face on the spinal tractus of the trigeminal nerve; that is, the most central areas of the face terminate highest on the nucleus caudalis, whereas the most peripheral areas of the face end lowest.37,41

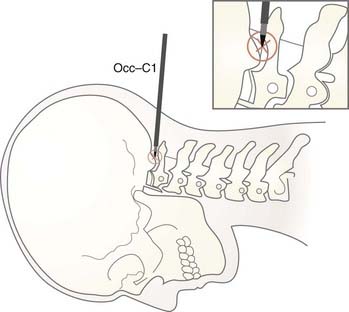

The target in tractotomy is located in the posterolateral part of the spinal cord. At this point, the descending trigeminal tractus is located in the lateral part and the nucleus caudalis in the median part. For this reason, during lesioning, the tractus as well as the oral part of the nucleus caudalis are destroyed. The procedure was designated TR-NC in view of this relationship (Fig. 172-2).

Patient Selection

Cordotomy

Cordotomy is the preferred method if the surgeon is certain that the patient’s intractable pain is transmitted in the lateral spinothalamic tract (see Figs. 172-1 and 172-3). The best candidates for cordotomy are patients with unilateral nociceptive somatic cancer pain and compression of the plexus, roots, or nerves.42 Tasker defined two types of pain as indications for cordotomy: (1) intermittent, neuralgia-like, shooting pain into the legs associated with a spinal cord injury, which is typically at the thoracolumbar level, and (2) evoked pain, allodynia or hyperpathia, associated with neuropathic pain syndromes that arise from peripheral neurological lesions.42,43

In our practice, percutaneous cordotomy is generally preferable. Open cordotomy is recommended if the necessary equipment is not available or the surgeon’s experience is inadequate to perform percutaneous cordotomy. The presence of any anomalies or other diseases of the upper cervical region would also be an indication for open cordotomy.42

Contrary to popular opinion, unilateral upper body pain (secondary to lung carcinoma, mesothelioma, or Pancoast’s tumors) and bilateral somatic intractable pain in the lower part of the body and extremities can be controlled by CT-guided, unilateral or bilateral selective cordotomy.23,24 Standard practice is to use neurodestructive procedures only after narcotic analgesics prove inadequate.44,45 Gybels proposed infusing opioid into cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and performing percutaneous neurolytic procedures instead of percutaneous cordotomy if the patient has only a 2- to 5-month life expectancy.46 At present, with the help of imaging techniques and the recent contribution of electrode technology, cordotomy can be performed safely and effectively. Thus, CT-guided percutaneous cordotomy should be considered the treatment of choice even before morphine therapy.23,24 I believe that the new version of percutaneous cordotomy is a simple, safe, and preferable procedure, especially for intractable pain states in malignancy, to stop patient dependence on pumps, stimulation systems, drugs, and doctors. Percutaneous cordotomy provides a rare opportunity to improve patients’ quality of life in their final and most difficult stages.

Cordotomy is contraindicated in patients with severe pulmonary dysfunction, those who are unable to stay in a supine position for 30 to 40 minutes, and patients whose oxygen saturation is less than 80%. For patients with bilateral intractable pain of the chest and arms, bilateral high cervical cordotomy is not recommended. For this group, the anterior approach must be used—open or percutaneous and unilateral or bilateral.23,24,42,47,48

Percutaneous Trigeminal Tractotomy-Nucleotomy

Trigeminal tractotomy-nucleotomy is based on the destruction of descending trigeminal tractus and nucleus caudalis at occiput-C1 level (Figs. 172-2 and 172-4). Trigeminal tractotomy or nucleotomy procedures, or both, are used for pain denervation in selected cases: cancer pain and deafferentation pain, atypical facial pain (AFP), atypical trigeminal pain, chronic cluster headache, and vagoglossopharyngeal and geniculate neuralgias located not only in the area of the 5th nerve but also in the area of the 7th, 9th, and 10th nerves and nucleus caudalis.16,19,49–55 AFP is a throbbing pain situated deep in the eye and malar region that often radiates to the ear, neck, and shoulders. The pain is not generally within any dermatomal or anatomic boundaries. AFP and psychological pathologies such as depression are strongly associated, and anxiety is known to exacerbate the condition. The term atypical is used to distinguish facial pain from trigeminal neuralgia because this pain syndrome is neither responsive to anticonvulsant drugs nor present in the sensory area of the trigeminal nerve.56 Some neurosurgeons do not recommend surgery for these patients, but we still accept patients if referred by psychiatrists for intractable AFP.

Percutaneous Cordotomy Technique

Instrumentation and Calibration of Electrode Systems

Percutaneous cordotomy is routinely performed with an RF system consisting of a generator, specially designed needles, and electrodes. The generator system must have an impedance measurement system, stimulation capability, and means for monitoring the temperature of the electrode system. The diameter and length of the uninsulated tip of the electrode are critical because lesion size is directly related to these parameters; thus, all parameters must be calibrated by making lesions in egg white before being applied intraoperatively. I recommend using an electrode kit57 with 20-gauge, thin-walled needles (cannulas) and plastic hubs designed to avoid imaging problems caused by artifacts. The kit also includes two open-tipped thermocouple electrodes with 2-mm tips and diameters of 0.25 mm and one straight-tipped and one curved-tipped electrode.

Preoperative Preparation

Before the procedure, cranial CT or magnetic resonance imaging must be performed to rule out brain metastasis because CSF loss during the procedure could theoretically result in brain herniation. The patient should have fasted for 5 hours preoperatively. The required dose of analgesic should be given parenterally before the procedure. At this stage, patients should be informed again of the details of the procedure. Clear communication and development of good rapport with the patient are crucial because success of the procedure is dependent on intraoperative feedback from the patient. In CT-guided percutaneous cordotomy, contrast material should be administered into the subarachnoid space of the spinal cord via lumbar puncture (7 to 8 mL of 240-mg/L iohexol) 20 to 30 minutes before the operation. If the general condition of the patient does not permit lumbar puncture, contrast material (5 mL of iohexol) is injected at the C1-2 level.2,39,56

Anatomic Localization

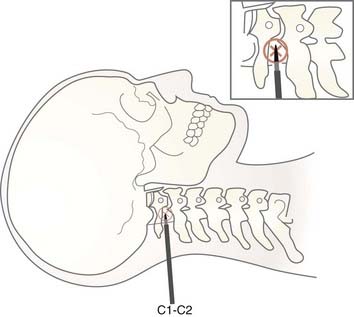

The electrode system is placed on the anterolateral aspect of the anterolateral spinal cord with the assistance of an imaging method. In conventional C1-2 lateral cordotomy, the needle is inserted perpendicularly, 1 cm below and behind the mastoid process after deep local infiltration of anesthetic (Fig. 172-4). I recommend confirmation of the infiltration site by repeated aspiration to avoid subarachnoid or vertebral artery puncture.

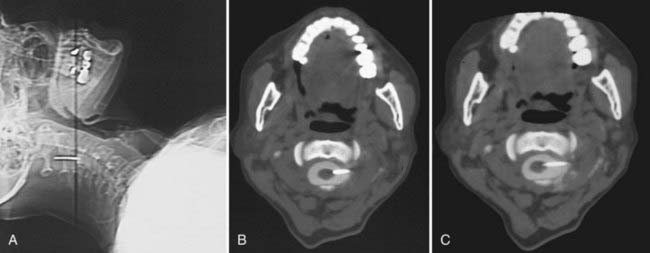

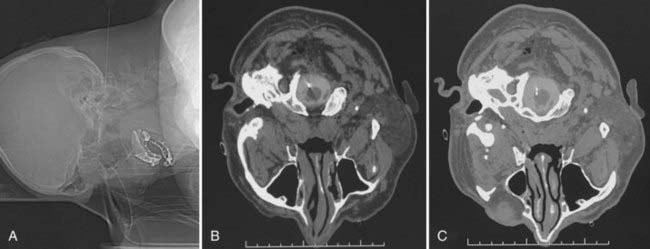

In CT-guided cordotomy, the skin-dura distance must be measured at this point. At this stage, the skin-dura distance and direction of the needle are well demonstrated on the CT image. Lahuerta and colleagues found this distance to be 57 ± 3 mm in males and 52 ± 2 mm in females.58 In my series, this distance was 46 to 66 mm (mean, 52.1 ± 4.3 mm) in males and 43 to 56 mm (mean, 48.4 ± 3.1 mm) in females. The next step is to place the needle 1 to 2 mm anterior to the dentate ligament. Because lateral puncturing of the dura usually causes pain, infiltration of a small amount of local anesthetic is recommended. The needle position is seen at every step of the manipulation on a lateral scanogram and axial CT scans by using a 1-mm slice thickness at the needle level (Fig. 172-5A). Multiple maneuvers under CT guidance may be needed to fix the needle in this position (Fig. 172-5B). The active electrode is then inserted into the cannula via one insertion (Fig. 172-5C).

Bilateral Cordotomy

Bilateral percutaneous cordotomy is usually performed with a 1-week interval. I recommend using bilateral selective cordotomy for intractable pain in the lower T10 dermatome. If the pain is located in the upper segment, C1-2 percutaneous lateral cordotomy is performed on one side and percutaneous anterior cordotomy on the other,48,59,60 although bilateral procedures may present technical difficulties.

Percutaneous Trigeminal Tractotomy-Nucleotomy Technique

Preoperative Preparation

TR-NC is performed at the occiput-C1 level, with the descending trigeminal tractus and nucleus caudalis of the spinal trigeminal nucleus being targets (see Fig. 172-2). Patients should have fasted for 5 hours before the operation.

Positioning and Anesthesia

As the first step, contrast material is injected into the subarachnoid space by lumbar puncture. If necessary, the contrast agent can be given at the occiput-C1 level at the beginning of the procedure. The patient is placed prone on the CT table with the head in a flexed position (Fig. 172-6B). The procedure can be difficult with some anatomic anomalies, especially obese patients with a short neck. Oxygen should be given at the required dose. A nasal catheter is necessary for administration of oxygen because of the face-down and flexed posture. Every level of the procedure must be explained to the patient. Subsequently, the contrast agent must be monitored to ensure homogeneous spread by obtaining slices from the upper spinal canal. Spinal cord diametral measurements are recorded. The operation can be painful, especially during insertion of the electrode tip into the tractus. After local anesthesia, the subarachnoid space is reached at the occipitocervical region with a 20-gauge needle specially designed for CT-guided procedures. The needle is inserted into skin 6 to 8 mm lateral to the midline at the C1-occiput level. The targets for destruction are the spinal trigeminal tractus and nucleus caudalis, which are located at the first third of the lateral midline and lateral surface of the upper spinal cord. It is described as being at a 3- to 3.5-mm depth from the surface of the spinal cord.17 In our diametral measurements, the depth of the electrode was between 2.8 and 4.6 mm. These measurements can vary and should be determined for each individual. At this point, placement of the needle can be visualized with the lateral scanogram, and the direction of the needle can be manipulated toward the occipitocervical space with the help of axial CT sections.

Anatomic Localization

At the C1-occiput level, the dura-skin distance ranges from 44 to 58 mm (mean, 50 mm) when the posterior paramedian approach is used. Diametral measurements of the spinal cord are made at the occiput-C1 level, and the inserted part (3 to 4 mm) of the active electrode is adjusted accordingly. Diameters were found to range from 7 to 12.8 mm (AP) (mean, 9.13 mm) and from 9.3 to 14 mm (T) (mean, 11.6 mm).27 After a lateral scanogram, axial CT slices are taken (Fig. 172-6A to C). By obtaining CT slices the surgeon can determine whether the electrode has penetrated the cord, any cord displacement, the extent of penetration of the electrode into the spinal cord, and whether the tip of the electrode has reached its target (Fig. 172-6C).

Physiologic Localization

Functional confirmation of the target is obtained by electrical stimulation. As described previously, the rostral dermatome is located ventrolaterally and the caudal dermatome dorsomedially.41,55,61 After correction of localization, the electrode is checked by impedance measurement and stimulation. RF lesions can then be made. Impedance values are approximately 100 to 200 Ω in CSF, increase to approximately 200 to 400 Ω when the electrode tip contacts the pia mater, and finally exceed 1000 Ω after insertion into the cord. Electrical stimulation at low (2 to 5 Hz, 0.3 to 1 V) and high (50 to 100 Hz, 0.1 to 0.3 V) frequencies is used.2,39 It should be remembered that high-voltage stimulation is painful at this point. Stimulation starts with minimum voltage. Paresthesia of the ipsilateral half of the face can be observed. If paresthesia of the face occurs, slight withdrawal of the tip and restimulation may cause a dysesthetic sensation in the throat or inside the ear, thus indicating that the tip is in the nociceptive fibers of the 7th, 9th, and 10th cranial nerves.

Lesion Making

Stimulating and lesioning of the tractus-nucleus complex may lead to painful, uncomfortable dysesthesia for the patient, at which point additional pain medication should be administered (we generally prefer fentanyl, 0.5 to 1 µg/kg, and midazolam, 0.05 to 0.1 mg/kg). Persistent lesions can usually be achieved with a tip temperature of greater than 60°C within 30 seconds. A maximum of two or three lesions should be performed. During lesioning, the energy and tip temperature are increased gradually, and neurological functions must be continuously tested. The final lesion is made at 70°C to 80°C for 60 seconds.2,39,56 This is the critical part of the procedure. Lesioning in the tractus is sometimes intolerable, in which case pain medication can be administered.

Results and Complications

Percutaneous Cordotomy

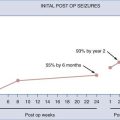

There was no mortality and very limited morbidity related to percutaneous cordotomy (temporary slight motor paralysis [n = 5] and ataxia [n = 5] [2.2%]). These complications resolved within 3 weeks in all cases. In bilateral cordotomy procedures, temporary hypotension and temporary urinary retention occurred in 3 and 2 patients, respectively. The only permanent complication after cordotomy in our series was dysesthesia, seen in 4 patients (1.8%). Lorenz and Sindou and Daher collected a large series from the literature.62,63 In their reports, percutaneous cordotomy was described as a risky procedure for the treatment of intractable pain, but these reports were published in 1976 and 1988. The new modality of cordotomy provides the opportunity of lesioning solely in the target area. In the report of Lahuerta and colleagues, complications usually occurred if the cordotomy lesion involved more than 20% of the spinal cord on the lesion side.58

Conclusion

Cordotomy and trigeminal TR-NC are not new procedures, and in principle they have not changed since their first application by Martin in 1911 and Sjöqvist in 1938.3,6 The goal of destructive pain procedures is to interrupt pain transmission in the pain-conducting pathways.

Since Mullan and associates’ discovery of percutaneous cordotomy, it has been routinely used with an RF system.12 The percutaneous application is performed under local anesthesia, which allows cooperation of the patient during the procedure and facilitates neurophysiologic monitoring and controlled lesioning of the target. In conventional percutaneous cordotomy, the most critical problem is that the visualization system, radiographic imaging, indirectly demonstrates the spinal cord. Even with the use of contrast material, only the dentate ligament plus the anterior and posterior borders of the spinal cord are visualized, not the spinal cord segment at the approach level. With radiographic imaging, individual spinal cord diameters, which are necessary for calibration of the depth of the inserted part of the active electrode, are not measured. Needle direction cannot be superimposed on the target to facilitate insertion of the active electrode in a morphologic orientation. Finally, the target-electrode relationship is not demonstrated directly.

The best results are obtained in carefully selected patients with the use of proper technique.

Crue BL, Carregal JA, Felsoory A. Percutaneous stereotactic radiofrequency. Trigeminal tractotomy with neurophysiological recordings. Confin Neurol. 1972;34:389-397.

Hitchcock ER. Stereotactic trigeminal tractotomy. Ann Clin Res. 1970;2:131-135.

Kanpolat Y. Cordotomy for pain, 5th ed. Winn HR, editor. Youmans Neurological Surgery, Vol 3. Philadelphia: WB Saunders. 2003:3059-3071.

Kanpolat Y. Percutaneous stereotactic pain procedures: percutaneous cordotomy, extralemniscal myelotomy, trigeminal tractotomy-nucleotomy. In: Burchiel K, editor. Surgical Management of Pain. New York: Thieme; 2002:745-762.

Kanpolat Y, Akyar S, Caglar S, et al. CT-guided percutaneous selective cordotomy. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1993;123:92-97.

Kanpolat Y, Akyar S, Çaglar S. Diametral measurements of the upper spinal cord for stereotactic pain procedures. Surg Neurol. 1995;43:478-483.

Kanpolat Y, Atalag M, Deda H, et al. CT-guided extralemniscal myelotomy. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1988;91:151-152.

Kanpolat Y, Cosman E. Special radiofrequency electrode system for computed tomography–guided pain-relieving procedures. Neurosurgery. 1996;38:600-603.

Kanpolat Y, Deda H, Akyar S, et al. CT-guided trigeminal tractotomy. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1989;100:112-114.

Kanpolat Y, Deda H, Akyar S, et al. CT-guided percutaneous cordotomy. Acta Neurochir (Suppl). 1989;46:67-68.

Kanpolat Y, Savas A, Caglar S, et al. Computerized tomography–guided percutaneous bilateral selective cordotomy. Neurosurg Focus. 1997;2(1):e5.

Kunc Z. Treatment of essential neuralgia of the 9th nerve by selective tractotomy. J Neurosurg. 1965;23:494-500.

Lahuerta J, Bowsher D, Lipton S, et al. Percutaneous cervical cordotomy: a review of 181 operations on 146 patients with a study on the location of “pain fibres” in the C-2 spinal cord segment of 29 cases. J Neurosurg. 1994;80:975-985.

Lin PM, Gildenberg PL, Polacoff PO. An anterior approach to percutaneous lower cervical cordotomy. J Neurosurg. 1966;25:553-560.

Lorenz R. Methods of percutaneous spinothalamic tract section. In: Krayenbühl H, Brihaye J, Loew F, et al, editors. Advances and Technical Standards in Neurosurgery. Vienna: Springer-Verlag; 1976:123-154.

Mullan S, Harper PV, Hekmatpanah J, et al. Percutaneous interruption of spinal-pain tracts by means of a strontium needle. J Neurosurg. 1963;20:931-939.

Mullan S, Hekmatpanah J, Dobben G, et al. Percutaneous, intramedullary cordotomy utilizing the unipolar anodal electrolytic lesion. J Neurosurg. 1965;22:548-555.

Nashold BS, el-Naggar A, Abdulhak MM, et al. Trigeminal nucleus caudalis dorsal root entry zone: a new surgical approach. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 1992;59:45-51.

Rosomoff HL, Carroll F, Brown J, et al. Percutaneous radiofrequency cervical cordotomy: technique. J Neurosurg. 1965;23:639-644.

Sjöqvist O. Discussion on the conduction of pain from the face. In: Sjöqvist O, editor. Studies on Pain Conduction in the Trigeminal Nerve. Helsinki: Mercators Tryckeri; 1938:85-93.

Spiller WG. The location within the spinal cord of the fibers for temperature and pain sensations. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1905;32:318-320.

Spiller WG, Martin E. The treatment of persistent pain of organic origin in the lower part of the body by division of the anterolateral column of the spinal cord. JAMA. 1912;58:1489-1490.

Taren JA, Kahn EA. Anatomic pathways related to pain in face and neck. J Neurosurg. 1962;19:116-121.

White JC, Sweet WH. Pain and the Neurosurgeon: A Forty Year Experience. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas; 1969.

1 Clarke E, O’Malley CD. Function of the spinal cord. In: Clarke E, O’Malley CD, editors. The Human Brain and the Spinal Cord. San Francisco: Norman Publishing; 1996:291-322.

2 Kanpolat Y. Cordotomy for pain, 5th ed. Winn HR, editor. Youmans Neurological Surgery, Vol 3. Philadelphia: WB Saunders. 2003:3059-3071.

3 Sjöqvist O. Discussion on the conduction of pain from the face. In: Sjöqvist O, editor. Studies on Pain Conduction in the Trigeminal Nerve. Helsinki: Mercators Tryckeri; 1938:85-93.

4 Spiller WG. The location within the spinal cord of the fibers for temperature and pain sensations. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1905;32:318-320.

5 Schüller A. Über operative Durchtrennung der Rückenmarksstrange (Chordotomie). Wien Med Wochenschr. 1910;60:2292-2295.

6 Spiller WG, Martin E. The treatment of persistent pain of organic origin in the lower part of the body by division of the anterolateral column of the spinal cord. JAMA. 1912;58:1489-1490.

7 Frazier CH. Section of the anterolateral columns of the spinal cord for the relief of pain. Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1920;4:137.

8 Collis JS. Anterolateral cordotomy by an anterior approach: report of a case. J Neurosurg. 1963;20:445-446.

9 Cloward RB. Cervical cordotomy by the anterior approach: technique and advantages. J Neurosurg. 1964;21:19-25.

10 White JC, Sweet WH. Pain and the Neurosurgeon: A Forty Year Experience. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas; 1969.

11 Kunc Z. Treatment of essential neuralgia of the 9th nerve by selective tractotomy. J Neurosurg. 1965;23:494-500.

12 Mullan S, Harper PV, Hekmatpanah J, et al. Percutaneous interruption of spinal-pain tracts by means of a strontium needle. J Neurosurg. 1963;20:931-939.

13 Mullan S, Hekmatpanah J, Dobben G, et al. Percutaneous, intramedullary cordotomy utilizing the unipolar anodal electrolytic lesion. J Neurosurg. 1965;22:548-555.

14 Rosomoff HL, Carroll F, Brown J, et al. Percutaneous radiofrequency cervical cordotomy: technique. J Neurosurg. 1965;23:639-644.

15 Lin PM, Gildenberg PL, Polacoff PO. An anterior approach to percutaneous lower cervical cordotomy. J Neurosurg. 1966;25:553-560.

16 Crue BL, Carregal JA, Felsoory A. Percutaneous stereotactic radiofrequency. Trigeminal tractotomy with neurophysiological recordings. Confin Neurol. 1972;34:389-397.

17 Hitchcock ER. Stereotactic trigeminal tractotomy. Ann Clin Res. 1970;2:131-135.

18 Hitchcock ER, Schvarcz JR. Stereotactic trigeminal tractotomy for post-herpetic facial pain. J Neurosurg. 1972;37:412-417.

19 Schvarcz JR. Stereotactic trigeminal tractotomy. Confin Neurol. 1975;37:73-77.

20 Schvarcz JR. Postherpetic craniofacial dysaesthesiae: their management by stereotactic trigeminal nucleotomy. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1977;38:65-72.

21 Kanpolat Y, Atalag M, Deda H, et al. CT-guided extralemniscal myelotomy. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1988;91:151-152.

22 Kanpolat Y, Deda H, Akyar S, et al. CT-guided percutaneous cordotomy. Acta Neurochir (Suppl). 1989;46:67-68.

23 Kanpolat Y, Akyar S, Caglar S, et al. CT-guided percutaneous selective cordotomy. Acta Neurochir (Wein). 1993;123:92-97.

24 Kanpolat Y, Savas A, Caglar S, et al. Computerized tomography–guided percutaneous bilateral selective cordotomy. Neurosurg Focus. 1997;2(1):e5.

25 Kanpolat Y, Deda H, Akyar S, et al. CT-guided trigeminal tractotomy. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1989;100:112-114.

26 Mullan S. Percutaneous cordotomy. J Neurosurg. 1971;35:360-366.

27 Kanpolat Y, Akyar S, Çaglar S. Diametral measurements of the upper spinal cord for stereotactic pain procedures. Surg Neurol. 1995;43:478-483.

28 Kameyama T, Hashizume Y, Sobue G. Morphologic features of the normal human cadaveric spinal cord. Spine. 1996;21:1285-1290.

29 Poletti CE. Open cordotomy and medullary tractotomy. In: Schmidek HH, Sweet WH, editors. Operative Neurosurgical Techniques. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1995:1557-1571.

30 Hyndman OR, Van Epps C. Possibility of differential section of the spinothalamic tract. A clinical and histological study. Arch Surg. 1939;38:1036-1053.

31 Walker EA. The spinothalamic tract in man. Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1940;43:284-298.

32 Peet MM. The control of intractable pain in the lumbar region, pelvis and lower extremities. Arch Surg. 1926;13:153-204.

33 Taren JA, Davis R, Crosby EC. Target physiologic corroboration in stereotaxic cervical cordotomy. J Neurosurg. 1969;30:569-584.

34 Nathan PW. The descending respiratory pathway in man. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1963;26:487-499.

35 Belmusto L, Brown E, Owens G. Clinical observations on respiratory and vasomotor disturbance as related to cervical cordotomies. J Neurosurg. 1963;25:225-232.

36 Hitchcock E, Leece B. Somatotopic representation of the respiratory pathways in the cervical cord of man. J Neurosurg. 1967;27:320-329.

37 Brodal A. Central course of afferent fibers for pain in facial, glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves. Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1947;57:292-307.

38 Hosobuchi Y, Rutkin B. Descending trigeminal tractotomy. Arch Neurol. 1971;25:115-125.

39 Kanpolat Y. Percutaneous stereotactic pain procedures: percutaneous cordotomy, extralemniscal myelotomy, trigeminal tractotomy-nucleotomy. In: Burchiel K, editor. Surgical Management of Pain. New York: Thieme; 2002:745-762.

40 Husain AM, Elliott SL, Gorecki JP. Neurophysiological monitoring for the nucleus caudalis dorsal root entry zone operation. Neurosurgery. 2002;50:822-827.

41 Taren JA, Kahn EA. Anatomic pathways related to pain in face and neck. J Neurosurg. 1962;19:116-121.

42 Tasker RR. Cordotomy for pain. In: Youmans JR, editor. Neurological Surgery. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1996:3463-3476.

43 Tasker RR, North R. Cordotomy and myelotomy. In: Tasker RR, North R, editors. Neurological Management of Pain. New York: Springer; 1997:191-220.

44 World Health Organization. Cancer Pain Relief and Palliative Care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1990.

45 Foley KM. The treatment of cancer pain. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:84-95.

46 Gybels JM. Indications for the use of neurosurgical techniques in pain control. In: Bond MR, Charlton JE, Wolf J, editors. Proceedings of the Sixth World Congress on Pain. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1995:475-482.

47 Amano K, Kawamura H, Tanikawa T, et al. Bilateral versus unilateral percutaneous high cervical cordotomy as a surgical method of pain relief. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 1991;52:143-145.

48 Fenstermaker RA, Sternau LL, Takaoka Y. CT-assisted percutaneous anterior cordotomy. Surg Neurol. 1995;43:147-150.

49 Bernard EJJr, Nashold BSJr, Caputi F, et al. Nucleus caudalis DREZ lesions for facial pain. Br J Neurosurg. 1987;1:81-91.

50 Burchiel KJ. A new classification for facial pain. Neurosurgery. 2003;53:1164-1167.

51 Elias WJ, Burchiel KJ. Trigeminal neuralgia and other neuropathic pain syndromes of the head and face. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2002;6:115-124.

52 Mertens P, Guenot M, Hermier M, et al. Radiologic anatomy of the spinal dorsal horn at the cervical level (anatomic-MRI correlations). Surg Radiol Anat. 2000;22(2):81-88.

53 Nashold BS, el-Naggar A, Abdulhak MM, et al. Trigeminal nucleus caudalis dorsal root entry zone: a new surgical approach. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 1992;59:45-51.

54 Siqueira JM. A method for bulbospinal trigeminal nucleotomy in the treatment of facial deafferentation pain. Appl Neurophysiol. 1985;48:277-280.

55 Teixeira MJ. Various functional procedures for pain. In: Gildenberg PL, Tasker RR, editors. Textbook of Stereotactic and Functional Neurosurgery. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1998:1389-1402.

56 Kanpolat Y. Spinal destructive procedures. CT-guided trigeminal tractotomy-nucleotomy. In: Batjer HH, Loftus CM, editors. Textbook of Neurological Surgery. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003:3049-3052.

57 Kanpolat Y, Cosman E. Special radiofrequency electrode system for computed tomography–guided pain-relieving procedures. Neurosurgery. 1996;38:600-603.

58 Lahuerta J, Bowsher D, Lipton S, et al. Percutaneous cervical cordotomy: a review of 181 operations on 146 patients with a study on the location of “pain fibres” in the C-2 spinal cord segment of 29 cases. J Neurosurg. 1994;80:975-985.

59 Lin MP. Percutaneous lower cervical cordotomy. In: Gildenberg PL, Tasker RR, editors. Textbook of Stereotactic and Functional Neurosurgery. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1998:1403-1409.

60 Gildenberg PL. Percutaneous cervical cordotomy. Clin Neurosurg. 1974;21:246-256.

61 Slavin KV, Nersesyan H, Colpan ME, et al. Current algorithm for the surgical treatment of facial pain. Head Face Med. 2007;3:30.

62 Lorenz R. Methods of percutaneous spinothalamic tract section. In: Krayenbühl H, Brihaye J, Loew F, et al, editors. Advances and Technical Standards in Neurosurgery. Vienna: Springer-Verlag; 1976:123-154.

63 Sindou M, Daher A. Spinal cord ablation procedures for pain. In: Dubner R, Gebhart GF, Bond MR, editors. Proceedings of the Vth World Congress on Pain. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1988:477-495.