Peptic ulceration and related disorders

Pathophysiology and epidemiology of peptic disorders

Pathophysiology of peptic ulceration

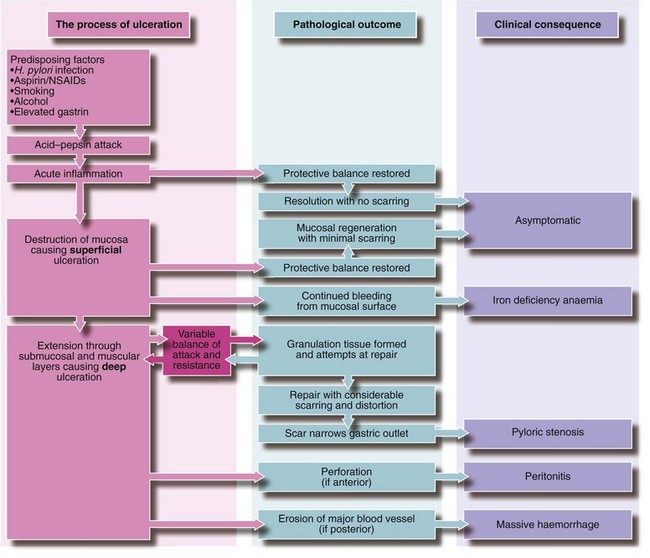

Inflammation, probably initiated by H. pylori infection and sustained by the combined effect of gastric acid and pepsin on the mucosa, is probably the cause of all peptic disorders of the upper gastrointestinal tract other than reflux oesophagitis. H. pylori is a Gram-negative microaerophilic spiral bacterium which has the ability to colonise the gastric mucosa over a very long period. In many cases, infection appears to have been acquired in childhood, often with poor living conditions in early life. Normally, a dynamic balance is maintained between the inherent protective characteristics of the mucosa (the mucosal barrier) and the irritant effects of acid–pepsin secretions. The delicate balance between the two may be disrupted by diminution of mucosal resistance or excessive acid–pepsin secretion or a combination of both. The mucosal surface may become eroded by direct action of an external agent, e.g. alcohol. Whatever the aetiology, the range of pathological outcomes is similar and is summarised in Figure 21.1.

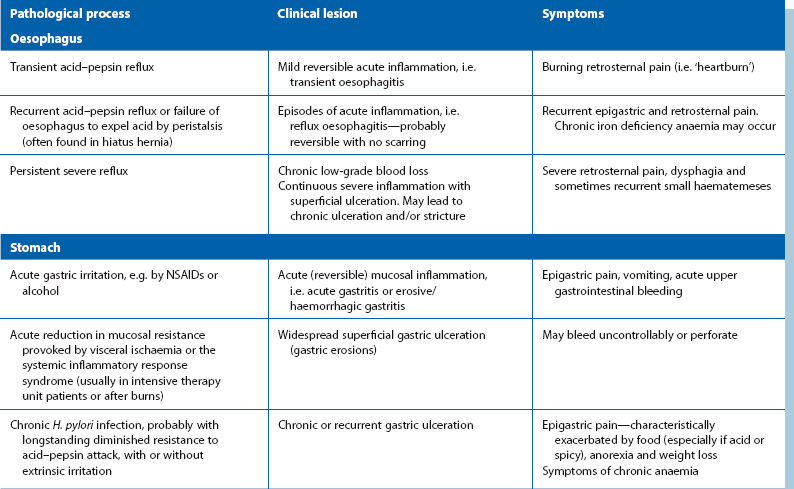

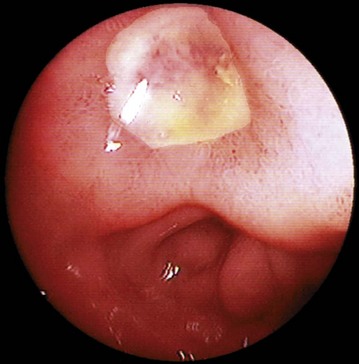

Fig. 21.1 Pathogenesis of peptic ulceration and its possible outcomes

Note that pain is a common factor in any active ulceration

Epidemiology and aetiology of peptic ulcer disease

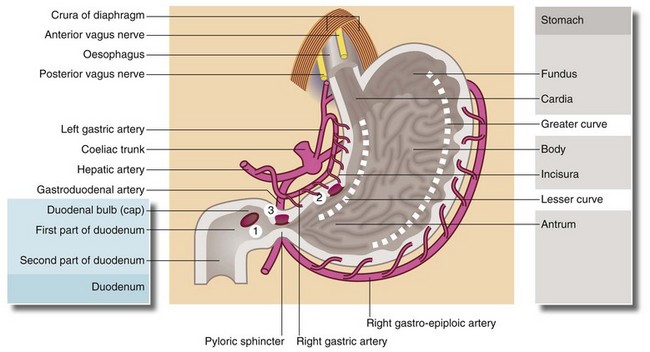

Sites of peptic ulceration (see Fig. 21.2)

Stomach and duodenum: The most common sites for chronic peptic ulcers are in the first part of the duodenum (the duodenal bulb) or the gastric antrum, particularly along the lesser curve. A chronic stomal ulcer may also appear at the margin of a surgically created communication between stomach and intestine (gastroenterostomy).

Fig. 21.2 Surgical anatomy of stomach and duodenum showing common sites of peptic ulceration

Acid secretion by the gastric mucosa is controlled by two mechanisms: (a) the vagus nerve stimulates acid secretion by the parietal cells (cholinergic stimulation) and (b) gastrin (produced by the APUD cells in the antrum) promotes secretion of acid and pepsin by the parietal and peptic cells of the fundus and body. The second is mediated via H2-receptors. (1) Marks the common site for duodenal ulcers which may be anterior or posterior; (2) the common site of lesser curve gastric ulcers; and (3) the site of pyloric channel ulcers

Oesophagus: Peptic inflammation and superficial ulceration may involve the lower oesophagus. It is almost always secondary to acid–pepsin reflux, and is often associated with hiatus hernia. H. pylori infection (see below) is probably not an important factor here. Reflux causes intermittent destruction of the lower oesophageal mucosa by acid or bile (or both), causing linear ulceration and prompting vigorous attempts at healing. One outcome is replacement of the normal squamous epithelium with metaplastic columnar mucosa. This is known as Barrett’s oesophagus and is one of the few known predisposing factors for adenocarcinoma of the lower oesophagus, a condition that has increased by 70% over the last 25 years (see Ch. 22, p. 311). Chronic peptic ulcers, similar to gastroduodenal ulcers, may also develop at the lower end of the oesophagus.

Aetiological factors in peptic disease

H. pylori infection: The importance of H. pylori infection as the main initiating factor in peptic ulceration has finally been universally accepted following the pioneering work of Dr Barry J. Marshall and Dr J. Robin Warren in Perth, Australia in the early 1980s. In a dramatic demonstration of Koch’s postulates, Marshall produced a duodenal ulcer in himself a few days after ingesting cultured H. pylori. The ulcer proved to be H. pylori-positive on biopsy and was cured by anti-Helicobacter antibiotic therapy. The pair won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for 2005 for their discovery of the bacterium and its role in gastritis and peptic ulcer disease. Before their work, it had been believed that microorganisms could not live in the highly acid environment of the normal stomach. However, gastric biopsies had frequently shown intramucosal bacteria, which they were eventually able to culture in vitro. These spiral-shaped organisms appear able to penetrate protective surface mucus and then accumulate in the region of intercellular junctions. There they may excite inflammation, stimulating excess acid–pepsin production or compromising normal protective mechanisms.

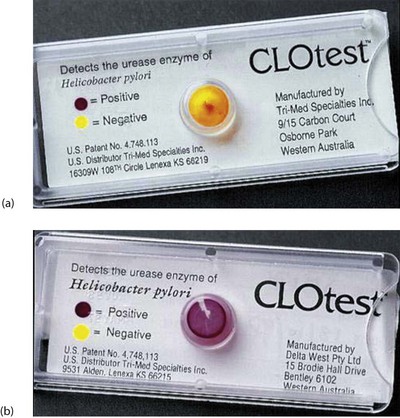

The jigsaw began to fit together when it was found that peptic ulcers could regularly be successfully treated with a combination of bismuth and antibiotics. Later work showed that H. pylori infection in duodenal ulcer patients was associated with a six-fold increase in gastric acid production which remitted when the infection was eliminated. There is now evidence that H. pylori is sometimes carcinogenic, initiating certain types of gastric lymphoma and some cases of gastric cancer. The broad picture is now evident: H. pylori causes a chronic infection with complications that include gastric and duodenal ulcer, gastric mucosa-associated lymphoma and gastric cancer. Only a small percentage of patients with duodenal or gastric ulcers are H. pylori negative. Tests for H. pylori infection include stool antigen tests, serum anti-H. pylori IgG and hydrogen breath tests. However, the most reliable method of diagnosis is endoscopic biopsies with immediate testing for urease produced by the organism (see below, Fig. 21.7) and histological examination of biopsy specimens.

Acid–pepsin production: Parietal cells secrete acid in direct or indirect response to acetylcholine, gastrin and histamine. It is likely that the common mediator is histamine via H2-receptors. The final common pathway for hydrogen ion secretion is via activation of a specific enzyme, H+/K+ ATPase, which exchanges hydrogen ions generated in the parietal cell for potassium ions in the gastric lumen using a mechanism known as the proton pump. In duodenal ulceration, the fundamental abnormality appears to be excessive production of acid–pepsin by the stomach, both basal (i.e. overnight) and stimulated. This may be a defensive response to H. pylori infection.

Mucosal resistance: There are several mechanisms which protect the upper gastrointestinal mucosa against autodigestion. Somatostatin and COX1 induced prostaglandins are inhibitors of parietal cell secretion and the latter have other cytoprotective properties. Two forms of mucus, soluble and insoluble, are secreted continuously by gastric and duodenal mucosa; they contain bicarbonate and together maintain the cell surface pH at neutrality.

Other mucosal irritants: Aspirin and other NSAIDs are known to induce acute mucosal inflammation directly (acute gastritis). In a susceptible individual, inflammation may persist, resulting in chronic ulceration. Prolonged heavy alcohol intake is also a recognised risk factor. The junction between parietal and antral cells on the lesser curvature of the stomach has been noted to be particularly vulnerable to gastric ulceration, although the reason is not understood. Cigarette smoking is twice as common in patients with chronic peptic ulcer disease as in the general population. Its pathogenic role is attributed to increased vagal activity, and its effect on producing relative gastric mucosal ischaemia. Ceasing smoking greatly assists in the healing of peptic ulcers.

Investigation and clinical features of peptic disorders

Investigation of suspected peptic ulcer disease

Endoscopy

In acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage, gastroscopy is almost mandatory, as described in Chapter 19. Gastroscopy can identify the site of the bleeding and is particularly useful if gastro-oesophageal varices are suspected to be the source of bleeding but are found not to be. Gastroscopy also allows recognition of features which can help stratify patients into low or high risk of rebleeding and it provides an important means of treating bleeding sites by injection of vasoconstrictors or sclerosants.

Presenting features of peptic ulcer disease

The various ways in which peptic inflammation affects the oesophagus, stomach and duodenum are summarised in Table 21.1.

Non-acute presentations of peptic ulcer disease

Peptic disorders of the oesophagus

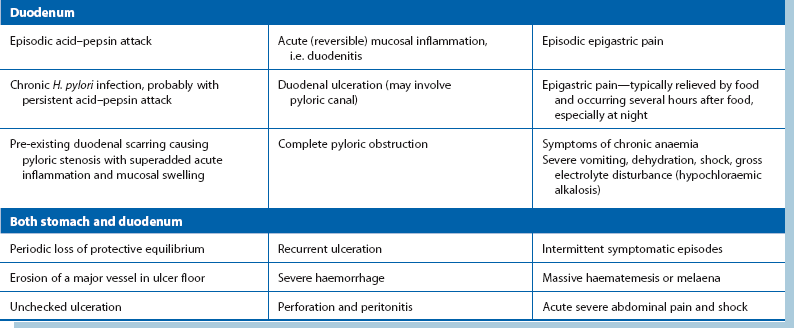

All peptic disorders of the oesophagus are associated with reflux of gastric contents. These disorders range from mild reversible inflammation, through moderate acute inflammation with superficial ulceration (reflux oesophagitis), to severe persistent inflammation which may lead to fibrotic scarring and stenosis (see Fig. 21.3) and sometimes chronic peptic ulceration. In many patients, reflux is associated with hiatus hernia (see Ch. 22).

On gastroscopy, reflux oesophagitis is characterised by mucosal reddening and, in more severe cases, by typical linear superficial ulceration (see Fig. 21.4). Peptic strictures occur in the distal oesophagus and are usually located just above the oesophago-gastric junction, which itself often lies above the diaphragm because of inflammatory shortening of the oesophagus. The normal oesophago-gastric junction is about 40 cm from the incisor teeth when seen on endoscopy. Specialised intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia and carcinoma must be excluded by biopsies because the visual appearances may not be characteristic. Occasionally, a deep chronic ulcer occurs in the lower oesophagus; this looks and behaves like an often linear gastric or duodenal ulcer. When squamous oesophageal epithelium is repeatedly damaged by reflux, it may be replaced by metaplastic columnar epithelium. This is known as Barrett’s oesophagus and there is strong evidence that it predisposes to malignant change. If found, it should be biopsied to exclude dysplasia. When dysplasia is severe, there is about a 1% annual risk of malignant change and endoscopic resection or surgery is necessary. Standard protocols are usually employed for surveillance of Barrett’s oesophagus with repeated endoscopy every 2–3 years.

Peptic disorders of the stomach

Gastritis: Gastritis appears as widespread reddening of the mucosa. If biliary reflux from the duodenum into the stomach is evident, the condition is sometimes referred to as ‘biliary gastritis’ on the assumption that it is caused by the irritant effect of biliary and pancreatic secretions. Acute gastritis, often caused by alcohol (chronic alcoholism or single alcoholic binges) or aspirin/NSAID ingestion, can cause symptoms of sufficient severity to warrant gastroscopy. The mucosa often exhibits patchy shallow ulceration (erosive gastritis) and is friable and easily traumatised, causing bleeding.

Stress ulcers: Acute ‘stress’ ulcers are single or multiple small discrete superficial lesions that may develop rapidly in seriously ill patients, often in intensive care units. The condition may be a complication of extensive burns, systemic sepsis (possibly via visceral hypoperfusion), multiple trauma, major head injuries, uraemia or terminal illness. Stress ulcers typically present with haemorrhage (haemorrhagic gastritis), which is sometimes catastrophic, and occasionally with perforation. There is minimal mucosal inflammation around the ulcers and the aetiology may be primarily mucosal ischaemia rather than peptic. The risk of this life-threatening complication can be minimised in vulnerable patients by prophylactic treatment with proton pump inhibitors.

Chronic gastric ulceration: Chronic gastric ulcers vary greatly in size but the majority are small (less than 2 cm in diameter). Giant ulcers (up to 10 cm) are occasionally seen in the elderly; if posteriorly situated, they may erode through the stomach wall, obliterating the lesser sac and adhering to the surface of the pancreas. In these cases, the ulcer base or floor is composed of pancreatic tissue and erosion may cause catastrophic haemorrhage.

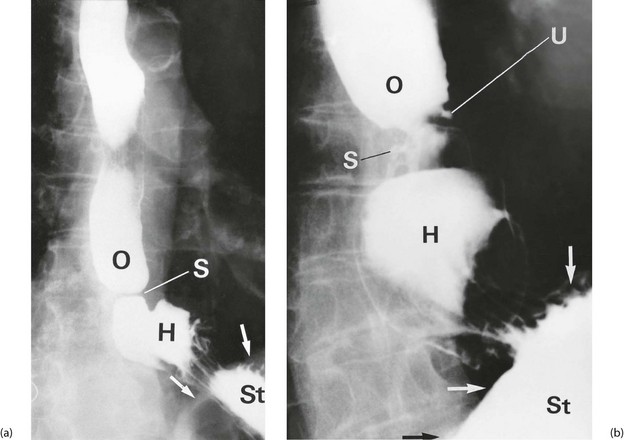

Benign gastric ulcers are typically regular in outline with a base consisting of white fibrinous slough. The ulcer gives the impression of having been punched out of the gastric wall, and there is no heaping-up of the mucosal margin as seen in malignant ulcers. The surrounding mucosa is surprisingly normal, although there may be radiating folds resulting from chronic fibrotic contractures. The typical endoscopic appearance of a gastric ulcer is shown in Figure 21.5a.

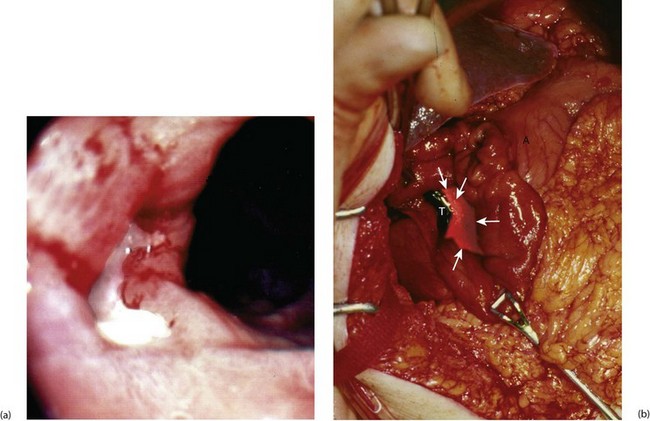

Fig. 21.5 Peptic ulcers

(a) Lesser curve benign gastric ulcer as seen through a gastroscope. At the original examination, the ulcer could be viewed from several directions and biopsies taken of the edge to exclude malignancy. (b) Photograph taken at emergency laparotomy for bleeding duodenal ulcer. The pylorus has been opened longitudinally and a deep chronic posterior ulcer crater is identified (arrowed). Thrombus T overlying an eroded artery is visible. A bleeding artery in the ulcer crater was under-run with sutures to arrest the haemorrhage

Peptic disorders of the duodenum

Duodenitis: Duodenitis, a non-ulcerative form of duodenal inflammation, has a similar endoscopic appearance to gastritis. It is commonly discovered in patients suspected of having duodenal ulceration, and probably represents a mild form of peptic disease.

Chronic duodenal ulceration: Chronic duodenal ulcers almost exclusively occur in the pyloric channel and the first part of the duodenum. The latter area is known endoscopically as the ‘duodenal bulb’ and radiologically as the ‘duodenal cap’. On endoscopy, duodenal ulcers have a range of appearances similar to chronic gastric ulcers. There is usually a single ulcer but two or more ulcers at one time are common (‘kissing ulcers’ occur on opposing walls of the duodenum). Malignancy is very rare in the duodenal bulb, so biopsy of the ulcer for this purpose is seldom necessary; biopsy of the gastric antrum for confirmation of H. pylori infections is, however, indicated. The endoscopic characteristics of a duodenal ulcer are shown in Figure 21.6.

Management of chronic peptic ulcer disease

The principles of modern management of peptic disorders are summarised in Box 21.1.

Control of predisposing or aggravating causes: The patient’s history may reveal adverse factors which can be easily eliminated. These are summarised at the start of Box 21.1. Radical dietary modification is unnecessary; patients should merely be advised to avoid food which they find aggravates the symptoms. Spicy or acidic foods are often blamed.

Elimination of proven H. pylori infection: Once H. pylori has been confirmed, treatment involves a course of acid inhibition combined with antibiotic treatment. Eradication usually produces long-term ulcer remission, and H. pylori reinfection is rare. A triple regimen including a proton pump inhibitor (e.g. omeprazole) and two antibiotics (clarithromycin plus either amoxicillin or metronidazole) given for 1 week eliminates Helicobacter in over 90% of cases, although increasingly strains of H. pylori are demonstrating antibiotic resistance and local antibiotic protocols should be followed. Longer courses give potentially higher elimination rates but produce more side-effects and lower compliance. Confirmation of eradication can be achieved by re-endoscopy and rapid urease testing (Fig. 21.7), or by breath testing.

Diminishing of irritant effects of acid–pepsin: An array of proprietary antacid preparations is available over the counter and on prescription. When used assiduously, they promote ulcer healing almost as effectively as any other drug, although more slowly. They all utilise a few main active ingredients. Sodium bicarbonate offers rapid but temporary relief of symptoms, while magnesium trisilicate or aluminium hydroxide promotes ulcer healing. Some of these agents, however, interfere with proton pump inhibitors. Colloidal bismuth compounds have been in use for many years. They have an antacid action and have been found to be active against H. pylori.

Administration of mucosal protective agents: Sucralfate is a complex of aluminium hydroxide and sulphated sucrose that is minimally absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract. It is believed to act by binding to denuded areas of mucosa and protecting them from acid–pepsin attack. It has been shown to be as effective as H2-blockers in providing symptom relief and healing when given in the dose of 2 g twice daily. It does not interfere with other drugs and is safe in pregnancy. It is also effective for preventing stress ulcers in seriously ill patients.

Reduction of acid secretion: Acid secretion by the gastric mucosa is normally controlled by two mechanisms:

• Direct cholinergic stimulation of parietal cells mediated via the vagus nerve. This is under reflex control originating in the cerebral cortex triggered by the sight and taste of food

• Gastrin is secreted by APUD cells in the gastric antrum and promotes acid secretion via histamine released from mast cells in the vicinity of the parietal cells. The histamine receptors on the parietal cells are distinct from those elsewhere in the body and are designated as type 2 (H2) receptors; these receptors are not blocked by standard ‘antihistamine’ drugs such as chlorphenamine. Gastrin secretion is partly controlled by the vagus and partly by local (vagally independent) reflexes initiated by gastric distension and the presence of food or alcohol in the stomach

From this, two practical methods have been found to reduce acid secretion: drugs which selectively block H2-receptors or the proton pump mechanism (described earlier), and surgical division of the vagus nerve.

H2-receptor blockade and proton pump antagonists: H2-receptor blocking drugs were developed in the 1970s and were the first ‘medical’ revolution in the management of peptic disorders. Cimetidine was the first but was joined by ranitidine, which has a few minor advantages but is no more effective for healing ulcers. H2-receptor antagonists are highly effective in reducing gastric acid secretion. Symptomatic response is rapid, usually within a day or two, and healing follows within a few weeks in 70–90% of cases. Recurrence rates, however, are high even with maintenance therapy, with 50–75% of patients developing further symptoms within 2 years.

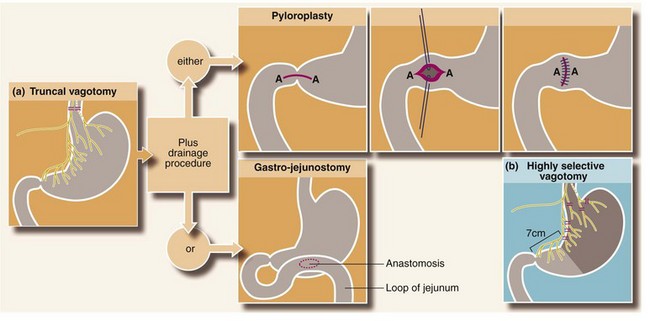

Vagotomy: Vagotomy was first performed in the 1920s and popularised by Dragstedt from 1943. It gradually superseded classic partial gastrectomy as the surgical treatment of choice for chronic duodenal ulcer. The vagotomy operations illustrated in Figure 21.8 are now only of historical interest. The simplest involved dividing the anterior and posterior vagal trunks close to the abdominal oesophagus just below the diaphragm (truncal vagotomy). The operation is effective in promoting ulcer healing but paralyses gastric motility and slows pyloric emptying. A surgical drainage procedure, usually pyloroplasty (‘V & P’), or less commonly gastro-jejunostomy, was therefore a necessary part of the operation.

Fig. 21.8 The vagotomies and gastric drainage procedures (rarely performed nowadays but of historical interest)

(a) Truncal vagotomy is followed by a drainage procedure, either pyloroplasty (Heinecke–Mikulicz is illustrated) or gastro-jejunostomy. In gastro-jejunostomy an anastomosis is created to the most dependent part of the stomach; a short efferent loop of jejunum is brought up either in front of the transverse colon and sutured to the anterior wall of the stomach (antecolic), or behind the transverse colon via an incision in the mesocolon and sutured to the posterior wall of the stomach (retrocolic). (b) Highly selective vagotomy does not require a drainage procedure. Only the parietal cell mass is denervated, preserving the innervation of the pylorus and antrum plus the rest of the abdominal viscera

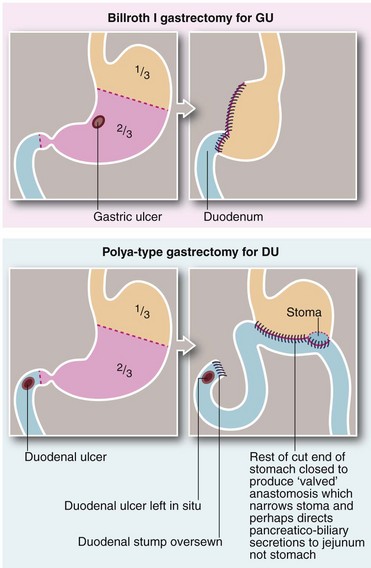

Surgical removal of intractable ulcers and gastrin-secreting tissue: Partial gastrectomy was occasionally used for patients where medical management had failed to heal a benign gastric ulcer or to treat repeated recurrences. The operation had the dual role of removing the ulcer and the gastrin-secreting mucosa. The classic gastrectomy for chronic gastric ulcer was known as the Billroth I type (Billroth, 1881) and involved removing the distal two-thirds of the stomach. The gastric remnant was then anastomosed to the first part of the duodenum (see Fig. 21.9).

The standard partial gastrectomy for duodenal ulcers was a Polya-type gastrectomy (Polya, 1911), also involving resection of the distal two-thirds of the stomach but anastomosing the cut end of the stomach to the side of a loop of proximal jejunum (gastro-jejunostomy). This is also known as a Billroth II operation. The cut end of the duodenum (duodenal stump) was closed and the ulcer left in situ to heal (see Fig. 21.9). Numerous variations on gastrectomy have been described over the years, but the essential difference is whether the gastric remnant is anastomosed to the duodenum (Billroth I-type) or to a jejunal loop (Polya-type).

Complications and side-effects of partial gastrectomy: The main complications of partial gastrectomy occur in the long term and may not become manifest for years (see Box 21.2). Recurrent ulceration after partial gastrectomy was rare and occurred in the gastric remnant or at the stomal margin. The usual reason was that insufficient stomach had been removed, but occasionally malignant change was responsible (3% risk over 15 years). Abnormally high acid production was another cause, sometimes due to Zollinger–Ellison syndrome or hyperparathyroidism.

Emergency presentations of peptic ulcer disease

Haemorrhage from a peptic ulcer

Acute bleeding from a peptic ulcer presents with haematemesis or melaena or both. Management is discussed in detail in Chapter 19.

Perforation of a peptic ulcer

Clinical presentation of perforated peptic ulcer: Perforation of a gastric or duodenal ulcer usually presents as a sudden onset of epigastric pain, rapidly spreading to the whole abdomen. The pain is continuous and is aggravated by moving about. Paradoxically, there may be vomiting of brownish or even blood-stained fluid. On examination, the patient is in obvious pain but is not shocked or toxic.

Diagnosis of perforated peptic ulcer: Diagnosis of an upper gastrointestinal perforation can usually be made from the symptoms and signs alone. A plain erect radiograph of the chest often reveals gas under the diaphragm, confirming the perforation of a hollow viscus but not its origin. This radiographic evidence of perforation, however, is not always present. If perforation is suspected but the signs are equivocal, an abdominal radiograph may be taken after the patient has swallowed 25 ml of water-soluble contrast; this may confirm the leakage. Diagnostic gastroscopy is contraindicated because the stomach must be inflated during this examination and air and gastric contents would erupt into the peritoneal cavity. CT scanning is commonly used and reveals free gas within the abdomen together with free fluid, although again the origin may not be clear. Laparoscopy is increasingly used to diagnose perforated ulcers.

Surgical management of peptic perforation: Emergency surgery is indicated in nearly all cases of upper gastrointestinal perforation. The patient is first resuscitated and a nasogastric tube inserted. The operation is most commonly performed at laparotomy, but laparoscopic management of perforated duodenal ulcers is now well established with equally good results. The principles are similar in either case. At surgery, the abdomen is inspected and the diagnosis confirmed. ‘Peritoneal toilet’ is performed to remove fluid and food contaminating the peritoneal cavity. A perforated duodenal ulcer is usually obvious as a punched-out hole near the pylorus. An anterior gastric perforation is also obvious, but a posterior gastric ulcer is not visible unless the lesser sac is opened, usually along the greater curve.

Conservative management of perforated duodenal ulcer: If an elderly, unfit patient presents late with a perforated duodenal ulcer, many surgeons treat this conservatively. This involves nasogastric aspiration, intravenous fluids, gastric acid suppression and antibiotics. Many of these patients who might otherwise have succumbed with major surgery recover satisfactorily.

Pyloric stenosis

Clinical features of pyloric stenosis: These patients rarely give any history of peptic ulcer pain but tend to present with a short history (a few weeks at most) of episodic and sometimes projectile vomiting. This is unrelated to eating, and the vomitus typically contains foul-smelling semi-digested food eaten a day or more previously. It does not contain green bile. Often patients do not seek medical advice until they have become severely dehydrated with gross electrolyte disturbance.

Biochemical abnormalities in pyloric stenosis: The biochemical disturbances in these patients are complex and depend on the volume and composition of fluid lost by vomiting and on the body’s compensatory mechanisms. Hydrogen and chloride are the principal ions lost in the vomitus. In response, the kidney conserves hydrogen ions by exchanging them for sodium ions (and some potassium ions), which are necessarily lost in the urine. The kidney also conserves chloride ions by exchanging them for bicarbonate ions. The net result may be a profound depletion of total body sodium (which is not accurately reflected in the plasma sodium level), profound hypochloraemia and profound metabolic alkalosis (hypochloraemic alkalosis). The plasma urea level is often high as a result of dehydration. Finally, the proportion of ionised calcium in the serum may fall as a result of the alkalosis, inducing tetany.

Management of pyloric stenosis: The first management priority in gastric outlet obstruction is resuscitation. Fluid and electrolyte deficiencies are corrected by infusion of physiological saline with added potassium chloride. The volume required often amounts to 10 litres or more. Rehydration will usually return the blood urea level to normal but may unmask anaemia serious enough to require blood transfusion.