Chapter 327 Peptic Ulcer Disease in Children

Ulcers in children can be classified as primary peptic ulcers, which are chronic and more often duodenal, or secondary, which are usually more acute in onset and are more often gastric (Table 327-1). Primary ulcers are most often associated with Helicobacter pylori infection; idiopathic primary peptic ulcers account for up to 20% of duodenal ulcers in children. Secondary peptic ulcers can result from stress due to sepsis, shock, or an intracranial lesion (Cushing ulcer) or in response to a severe burn injury (Curling ulcer). Secondary ulcers are often the result of using aspirin or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs); hypersecretory states like Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (Chapter 327.1), short bowel syndrome, and systemic mastocytosis are rare causes of peptic ulceration.

Table 327-1 ETIOLOGIC CLASSIFICATION OF PEPTIC ULCERS

NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

* Requires search for other specific causes.

From Vakil N, Megraud F: Eradication therapy for Helicobacter pylori, Gastroenterology 133:985–1001, 2007.

Pathogenesis

Primary Ulcers

Helicobacter Pylori Gastritis

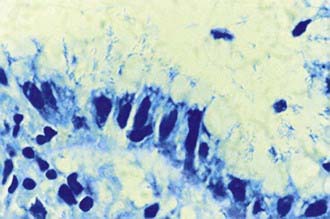

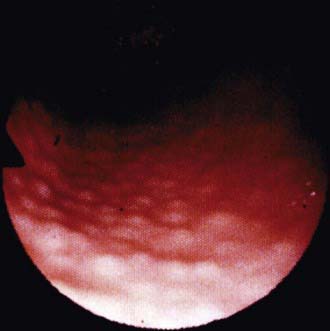

The diagnosis of H. pylori infection is made histologically by demonstrating the organism in the biopsy specimens (Fig. 327-1). Although serologic assays using validated immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody detection may be helpful for screening children for the presence of H. pylori, they do not help predict active infection or assess the success of antimicrobial eradication therapy. 13C-urea breath tests and stool antigen tests are also noninvasive methods of detecting H. pylori infection. Nonetheless, for children with suspected H. pylori infection, an initial upper endoscopy is recommended to evaluate and confirm H. pylori disease. The range of endoscopic findings in children with H. pylori infection varies from being grossly normal to the presence of nonspecific gastritis with prominent rugal folds, nodularity (Fig. 327-2), or ulcers. Because the antral mucosa appears to be endoscopically normal in a significant number of children with primary H. pylori gastritis, gastric biopsies should always be obtained from the body and antrum of the stomach regardless of the endoscopic appearance. If H. pylori is identified, even in a child with no symptoms, eradication therapy should be offered (Tables 327-2 and 327-3).

Figure 327-1 Appearance of Helicobacter pylori on the gastric mucosal surface with Giemsa stain (high-power view).

(From Campbell DI, Thomas JE: Heliobacter pylori infection in paediatric practice, Arch Dis Child Edu Pract Ed 90:ep25–ep30, 2005.)

Figure 327-2 Endoscopic view of lymphoid modular hyperplasia of the gastric antrum.

(From Campbell DI, Thomas JE: Heliobacter pylori infection in paediatric practice, Arch Dis Child Edu Pract Ed 90:ep25–ep30, 2005.)

Table 327-2 RECOMMENDED ERADICATION THERAPIES FOR H. PYLORI–ASSOCIATED DISEASE IN CHILDREN

| MEDICATIONS | DOSE | DURATION OF TREATMENT |

|---|---|---|

| Amoxicillin | 50 mg/kg/day in 2 divided doses | 14 days |

| Clarithromycin | 15 mg/kg/day in 2 divided doses | 14 days |

| Proton pump inhibitor | 1 mg/kg/day in 2 divided doses | 1 mo |

| or | ||

| Amoxicillin | 50 mg/kg/day in 2 divided doses | 14 days |

| Metronidazole | 20 mg/kg/day in 2 divided doses | 14 days |

| Proton pump inhibitor | 1 mg/kg/day in 2 divided doses | 1 mo |

| or | ||

| Clarithromycin | 15 mg/kg/day in 2 divided doses | 14 days |

| Metronidazole | 20 mg/kg/day in 2 divided doses | 14 days |

| Proton pump inhibitor | 1 mg/kg/day in 2 divided doses | 1 mo |

Adapted from Gold BD, Colletti RB, Abbott M, et al: Medical position statement: The North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. Helicobacter pylori infection in children: recommendations for diagnosis and treatment, J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 31:490–497, 2000.

Table 327-3 ANTISECRETORY THERAPY WITH PEDIATRIC DOSAGES

| MEDICATION | PEDIATRIC DOSE | HOW SUPPLIED |

|---|---|---|

| H2 RECEPTOR ANTAGONISTS | ||

| Cimetidine | 20-40 mg/kg/day Divided 2 to 4 × a day |

Syrup: 300 mg/mL Tablets: 200, 300, 400, 800 mg |

| Ranitidine | 4-10 mg/kg/day Divided 2 or 3 × a day |

Syrup: 75 mg/5 mL Tablets: 75, 150, 300 mg |

| Famotidine | 1-2 mg/kg/day Divided twice a day |

Syrup: 40 mg/5 mL Tablets: 20, 40 mg |

| Nizatidine | 10 mg/kg/day Divided twice a day |

|

| PROTON PUMP INHIBITORS | ||

| Omeprazole | 1.0-3.3 mg/kg/day <20 kg: 10 mg/day >20 kg: 20 mg/day Approved for use in those >2 yr old |

Capsules: 10, 20, 40 mg |

| Lansoprazole | 0.8-4 mg/kg/day <30 kg: 15 mg/day >30 kg: 30 mg/day Approved for use in those >1 yr old |

Capsules: 15, 30 mg Powder packet: 15, 30 mg Solu-tab: 15, 30 mg |

| Rabeprazole | Adult dose: 20 mg/day | Tablet: 20 mg |

| Pantoprazole | Adult dose: 40 mg/day | Tablet: 40 mg |

| CYTOPROTECTIVE AGENTS | ||

| Sucralfate | 40-80 mg/kg/day | Suspension: 1,000 mg/5 mL Tablet: 1,000 mg |

Treatment

Ulcer therapy has two goals: ulcer healing and elimination of the primary cause. Other important considerations are relief of symptoms and prevention of complications. The first-line drugs for the treatment of gastritis and peptic ulcer disease in children are H2 receptor antagonists and PPIs (see Table 327-3). PPIs are more potent in ulcer healing. Cytoprotective agents can also be used as adjunct therapy if mucosal lesions are present. Antibiotics in combination with a PPI must be used for the treatment of H. pylori-associated ulcers (see Table 327-2).

Treatment of H. Pylori–Related Peptic Ulcer Disease

In pediatrics, antibiotics and bismuth salts have been used in combination with PPIs to treat H. pylori infection (see Table 327-2). Eradication rates in children range from 68% to 92% when the dual or triple therapy is used for 4-6 wk. The ulcer healing rate ranges from 91% to 100%. Triple therapy yields a higher cure rate than dual therapy. The optimal regimen for the eradication of H. pylori infection in children has yet to be established, but the use of a PPI in combination with clarithromycin and amoxicillin or metronidazole for 2 wk is a well-tolerated and recommended triple therapy (see Table 327-2). Although children <5 yr of age can become reinfected, the most common reason for treatment failure is poor compliance or antibiotic resistance. H. pylori has become more resistant to clarithromycin or metronidazole due to the extensive use of these antibiotics for other infections. In the case of resistant H. pylori infection, sequential treatment or rescue therapy with different antibiotics is acceptable options. The sequential treatment regimen is a 10-day treatment consisting of a PPI and amoxicillin (both twice daily) administered for the first 5 days followed by triple therapy consisting of a PPI, clarithromycin, and metronidazole for the remaining 5 days. Levofloxacin, rifabutin, or furazolidone can be used with amoxicillin and bismuth as a rescue therapy depending on the age of the patient. Fidaxomicin has equivalent efficacy to vancomycin in adults. Knowledge of the community’s H. pylori resistance pattern to clarithromycin or metronidazole might help chose the initial or rescue therapy.

Calvet X, Lario S, Ramierez-Lazaro M, et al. Comparative accuracy of 3 monoclonal stool tests for diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection among patients with dyspepsia. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:323-328.

Campbell DI, Thomas JE. Heliobacter pylori infection in paediatric practice. Arch Dis Child Edu Pract Ed. 2005;90:ep25-ep30.

Chan FKL. Proton-pump inhibitors in peptic ulcer disease. Lancet. 2008;372:1198-1200.

Czinn SJ. Heliobacter pylori infection: detection, investigation, and management. J Pediatr. 2005;146:S21-S26.

Drumm B, Day AS, Gold B, et al. Helicobacter pylori and peptic ulcer: Working Group Report of the Second World Congress of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;39:S626-S631.

Gatta L, Vakil N, Leandro G, et al. Sequential therapy or triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in adults and children. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:3069-3079.

Gralnek IM, Barkun AN, Bardou M. Management of acute bleeding from a peptic ulcer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:928-936.

Jafri NS, Hornung CA, Howden CW. Meta-analysis: sequential therapy appears superior to standard therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection in patients naïve to treatment. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:923-931.

Kato S, Sherman PM. What is new related to Heliocobacter pylori infection in children and teenagers? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:415-421.

Lee BH, Kim N. Quadruple or triple therapy to eradicate H pylori. Lancet. 2011;377:877-878.

Malfertheiner P, Chan FKL, McCall KEL. Peptic ulcer disease. Lancet. 2009;374:1449-1458.

The Medical Letter. Treatment of Clostridium difficile infection. Med Lett. 2011;53(1358):14-15.

Sabbi T, De Angelis P, Colistro F, et al. Efficacy of noninvasive tests in the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection in pediatric patients. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:238-241.

Shah R. Dyspepsia and Helicobacter pylori. BMJ. 2007;334:41-43.

Stray-Pedersen A, et al. Helicobacter pylori antigen in stool is associated with SIDS and sudden infant deaths due to infectious diseases. Pediatr Res. 2008;64:405-410.

Subramanian V, Hawkey CJ. Assessing bleeds clinically: what’s the score? Lancet. 2009;373:5-7.