77 Penetrating Neck Trauma

• Thorough vascular and esophageal evaluation is required, even with minor neck wounds, if any abnormalities are evident on examination or radiographs.

• Radiographs do not rule out esophageal injury.

• Early airway management is crucial, with orotracheal intubation being the initial method of choice.

• A thorough neurologic examination is essential in all patients with neck trauma.

• “Hard signs” of vascular injury include bruit, thrill, expanding or pulsatile hematoma, pulsatile or severe hemorrhage, pulse deficit, and central nervous system ischemia.

• The “gold standard” for diagnosing vascular injury is conventional angiography.

• Admission criteria include signs and symptoms of organ damage and penetration of the platysma muscles.

Epidemiology

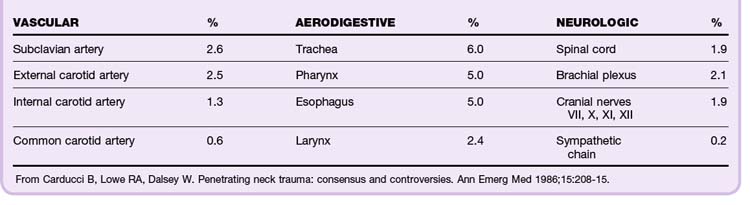

The incidence of injuries to the critical airway and the vascular, gastrointestinal, skeletal, and neurologic organs depends on the location and mechanism of injury. In the case of interpersonal violence, the distance between the assailant and victim and the type of weapon must be established. In total, 44% of injuries to critical organs involve vascular structures. This is a major source of morbidity and mortality (Table 77.1).1

Perspective

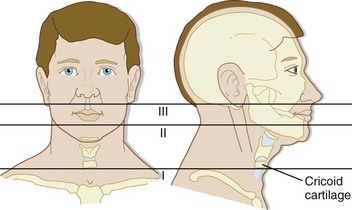

In the Vietnam War, the mortality from penetrating neck injuries was 4% to 7%. The current mortality rate in civilians is approximately 2% to 6%. Patients with zone I injuries (Fig. 77.1) at the base of the neck are at highest risk. Currently, spinal cord injuries and thrombosis of the common and internal carotid arteries account for 50% of all deaths from penetrating neck injury.

Anatomy

The neck consists of three anatomic zones (see Fig. 77.1):

• Zone I—base of the neck to the cricoid cartilage (Fig. 77.2)

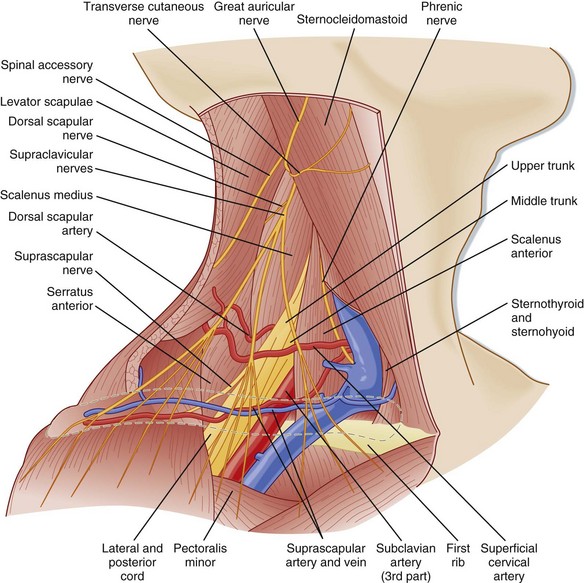

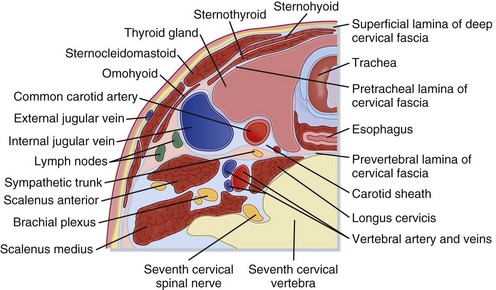

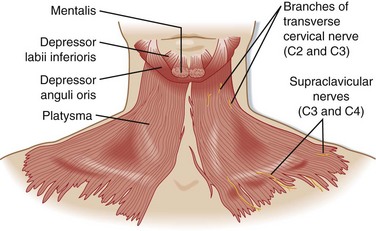

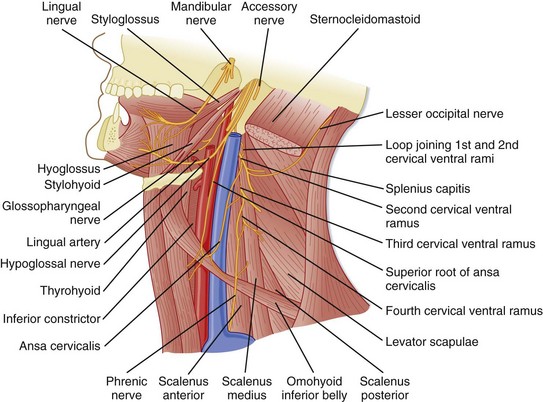

The major muscles of the neck are the platysma muscles, which extend from the lower jaw to the clavicle (Fig. 77.4). Other critical structures are shown in Figures 77.5 through 77.7.

Fig. 77.4 Surface anatomy: the platysma.

(From Agur AMR, Dalley AF, editors. Grant’s atlas of anatomy. 9th ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1991.)

Fig. 77.5 Anterior triangle—anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle to the midline.

(From Agur AMR, Dalley AF, editors. Grant’s atlas of anatomy. 9th ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1991.)

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Airway Injury

Symptoms of airway injury include dyspnea, hemoptysis, subcutaneous air, stridor, hoarseness, and dysphonia (Fig. 77.8).

Vascular Injury

“Hard signs” that indicate severe vascular injury include the following:

• Bruit or thrill suggestive of a traumatic arteriovenous fistula

• Expanding or pulsatile hematoma

• Pulsatile or severe hemorrhage

• Pulse deficit—pulses may be normal in patients with nonocclusive injuries that require surgical repair, such as intimal flaps or pseudoaneurysms

“Soft signs,” which are less predictive of severe vascular injury, include the following:

• Stable, nonpulsatile hematoma

• Central nervous system ischemia—a neurologic deficit that develops over the course of 1 to 2 hours after injury is consistent with ischemic neurologic injury; an immediate deficit is more likely to be due to a primary neurologic injury

• Proximity to a major vascular structure is not considered a high-risk feature in the absence of the preceding criteria (Fig. 77.9)

Diagnostic Testing

Vascular Injury

Conventional Angiography

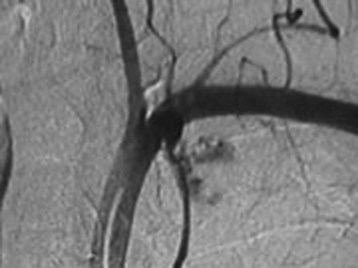

The “gold standard” of diagnostic modalities is four-vessel angiography with venous-phase imaging (sensitivity > 99%) (Fig. 77.10). Very rarely do injuries missed by angiography require repair. A normal study is highly predictive of survival from vessel injury.2

Duplex Ultrasonography

Duplex ultrasonography is noninvasive, convenient, and relatively inexpensive, but its sensitivity in detecting vascular injury is highly operator dependent. However, its sensitivity in comparison with conventional angiography is 90% to 100% for injuries requiring intervention.3 Duplex ultrasonography can miss nonocclusive injuries with preserved flow, such as intimal flaps and pseudoaneurysms.

Multidetector Helical Computed Tomographic Angiography

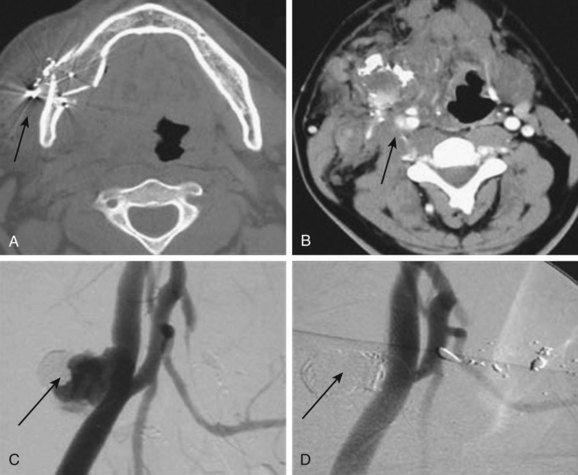

This diagnostic modality has largely supplanted duplex ultrasonography in patients without obvious indications for immediate operative intervention (Fig. 77.11). The sensitivity of multidetector computed tomographic (MDCT) angiography is 90% to 100% with respect to conventional angiography and surgical exploration.4,5

Pharyngeal Injury

Hypopharyngeal injuries may be difficult to visualize on radiographic contrast swallow studies, especially if patients are intubated. Videolaryngoscopy is an alternative diagnostic modality that is effective in detecting these injuries.6

Esophageal Injury

Esophageal injuries may be clinically silent initially. Radiographs do not exclude esophageal injury. Contrast-enhanced studies have a sensitivity of 50% to 90%. Esophagoscopy has a sensitivity of 43% to 100% (Table 77.2).

Table 77.2 Sensitivities of Diagnostic Modalities for Esophageal Injury

| DIAGNOSTIC TEST | SENSITIVITY (%) |

|---|---|

| Physical examination | 80 |

| Contrast-enhanced study | 89 |

| Rigid esophagoscopy | 89 |

| Contrast-enhanced study plus esophagoscopy | 100 |

From Weigelt JA, Thal ER, Snyder 3rd WH, et al. Diagnosis of penetrating cervical esophageal injuries. Am J Surg 1987;154:619–22.

Rigid endoscopy has higher diagnostic yield than flexible endoscopy does; however, it is associated with a higher incidence of complications, including iatrogenic rupture. A combined approach that includes both contrast-enhanced studies and esophagoscopy has a sensitivity of 100%.7,8

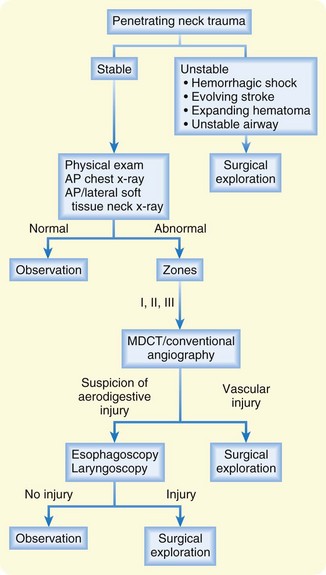

Selective Evaluation

Selective surgical exploration is recommended for patients without obvious indications for surgical repair.9–13 Nonoperative techniques (Fig. 77.12) are sufficiently sensitive to safely rule out injuries that require an operation. Esophageal and arterial injuries have reportedly been missed during exploration. A selective approach is more cost-effective than mandatory exploration.

Treatment

Airway Interventions

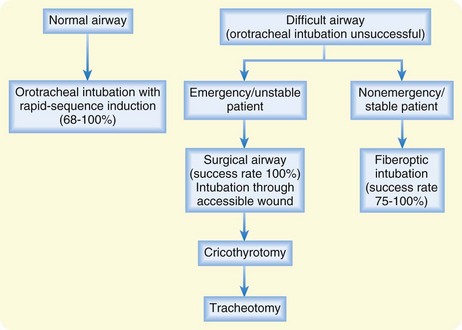

Direct visualization of the airway is optimal, and orotracheal intubation is the initial method of choice because the procedure is frequently performed and rarely associated with complications.14,15 Ideally, intubation is accomplished with topical anesthesia while the patient is awake.16 If not possible, rapid-sequence induction should be performed. Fiberoptic intubation is reserved for semielective airway management unless an experienced operator and the necessary equipment are immediately available. Visualization may be impaired because of extensive hemorrhage and secretions.

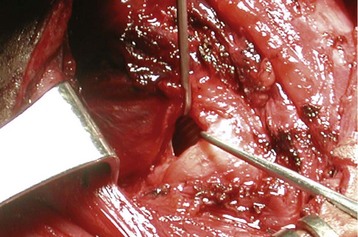

Cricothyrotomy or tracheostomy is necessary if orotracheal or fiberoptic intubation is unsuccessful. A surgical airway should not be delayed because an expanding hematoma can quickly distort the anatomy and result in complications. Intubation through an accessible neck wound has a very high success rate (Fig. 77.14). In this instance, care must be taken to control the proximal end of the trachea so that it does not retract into the thorax.

Nasotracheal intubation is not a preferred airway technique. Its success rate varies from 0% to 75%. It is potentially associated with complications because of the “blind” nature of the procedure. A more direct, visualized approach is suggested (Fig. 77.15).

Wound Care and Evaluation

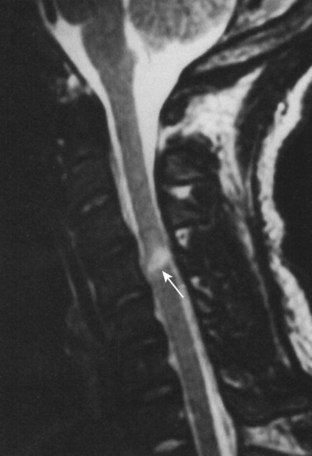

Cervical Spine Injury

Rigorous spinal precautions should not be maintained at the expense of managing life-threatening airway or vascular injuries in patients who are awake and neurologically intact without focal deficits.17,18 Unstable spine fractures are almost invariably associated with focal neurologic deficits or altered mental status. Early fracture stabilization and fixation are mandatory. Corticosteroids have no role in spinal cord injury caused by penetrating trauma.

1 Carducci B, Lowe RA, Dalsey W. Penetrating neck trauma: consensus and controversies. Ann Emerg Med. 1986;15:208–215.

2 Snyder WH, Thal ER, Bridges RA, et al. The validity of normal arteriograms in penetrating trauma. Arch Surg. 1978;113:424–426.

3 Kuzniec S, Kauffman P, Molnar LJ, et al. Diagnosis of limb and neck arterial trauma using duplex ultrasonography. Cardiovasc Surg. 1998;6:358–366.

4 LeBlang SD, Nunez DB, Rivas LA, et al. Helical computed tomographic angiography in penetrating neck trauma. Emerg Radiol. 1997;4:200–206.

5 Munera F, Soto JA, Palacio D, et al. Diagnosis of arterial injuries caused by penetrating trauma to the neck: comparison of helical CT angiography and conventional angiography. Radiology. 2000;216:356–362.

6 Ahmed N, Massier C, Tassie J, et al. Diagnosis of penetrating injuries of the pharynx and esophagus in the severely injured patient. J Trauma. 2009;67:152–154.

7 Weigelt JA, Thal ER, Snyder WH, et al. Diagnosis of penetrating cervical esophageal injuries. Am J Surg. 1987;154:619–622.

8 Gonzalez RP, Falimirski M, Holevar MR, et al. Penetrating zone II neck injury: does dynamic computed tomographic scan contribute to the diagnostic sensitivity of physical examination for surgically significant injury? A prospective blinded study. J Trauma. 2003;54:61–64. discussion 64–65

9 Biffl WL, Moore EE, Rehse DH, et al. Selective management of penetrating neck trauma based on cervical level of injury. Am J Surg. 1997;174:678–682.

10 Van As AB, Van Deurzen DF, Verleisdonk EJ, et al. Gunshots to the neck: selective angiography as part of conservative management. Injury. 2002;33:453–456.

11 Tisherman SA, Bokhari F, Collier B. Clinical practice guideline: penetrating zone II neck trauma. J Trauma. 2008;64:1392–1405.

12 Vogel SB, Rout WR, Martin TD, et al. Esophageal perforation in adults. Aggressive conservative treatment lowers morbidity and mortality. Ann Surg. 2005;241:1016–1021. discussion 1021–3

13 Goudy SL, Miller FB, Bumpous JM. Neck crepitance: evaluation and management of suspected upper aerodigestive tract injury. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:791–795.

14 Shearer VE, Giesecke AH. Airway management for patients with penetrating neck trauma: a retrospective study. Anesth Analg. 1993;77:1135–1138.

15 Eggen JT, Jorden RC. Airway management, penetrating neck trauma. J Emerg Med. 1993;11:381–385.

16 Tallon J, Ahmed JM, Sealy JM. Airway management in penetrating neck trauma at a Canadian tertiary trauma centre. CJEM. 2007;9:101–104.

17 Medzon R, Rothenhaus T, Bono CM, et al. Stability of the cervical spine after gunshot wounds to the head and neck. Spine. 2005;30:2274–2279.

18 Connell RA, Graham CA, Munro PT. Is spinal immobilization necessary for all patients sustaining isolated penetrating trauma? Injury. 2003;34:912–914.