CHAPTER 29 PENETRATING NECK INJURIES: DIAGNOSIS AND SELECTIVE MANAGEMENT

The neck has been a source of tremendous interest in the trauma surgical literature for several hundred years. Its anatomic compactness places vital anatomic structures in close proximity to each other making the patient prone to multisystem injuries as the result of a single traumatic event. The debate about the proper treatment of neck trauma has persisted since the 16th century when Ambroise Paré reportedly attended to a victim of a laceration to the common carotid artery and internal jugular vein sustained in a duel. While Paré’s patient survived, he was rendered hemiplegic and aphasic. Complications still highlight discussions today regarding the appropriateness of aggressive surgical management of penetrating cervical injuries.

ANATOMY OF THE NECK

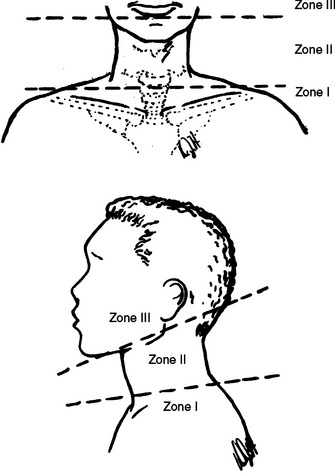

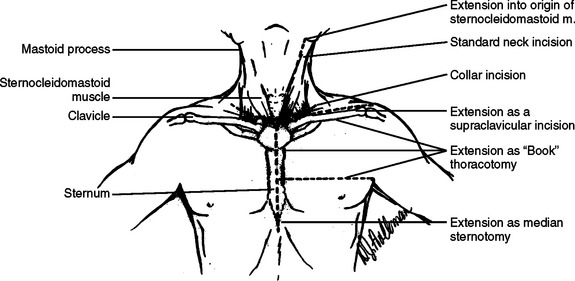

The neck is conventionally divided into a series of triangles.1 Most surgical discussions center on the anatomy of the anterior triangles which encompass the area between the sternocleidomastoid muscles. Functionally, the neck is divided into three zones (Figure 1). The boundaries for zone 1 include the cricoid cartilage (superiorly), the thoracic inlet (interiorly), and the sternocleidomastoid (laterally). Its surgical significance is the fact that this zone encompasses the major cervicothoracic vasculature, along with components of the aero-digestive tract. Zone III is the horizontal region of the neck cephalad to the angle of the mandible which superior border is the base of skull. It is important to note that the internal carotid artery which is cephalad to the angle of the mandible is not readily accessible surgically, necessitating special maneuvers to achieve vascular control (e.g., surgical dislocation of the mandible). However, zone II (the area between the cricoid cartilage and the angle of the mandible), is readily accessible with the most direct surgical approach being achieved with an incision along the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (Figure 2).

INITIAL EVALUATION

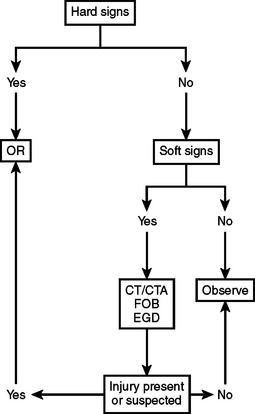

The initial evaluation of the patient suffering neck injury should be dictated by the Advanced Trauma Life Support® guidelines. Such guidelines provide a management framework to expeditiously identify life-threatening injuries and appropriately prioritize treatment. Presentations which warrant urgent surgical intervention, usually referred to as “hard signs” (Table 1) of neck injury, include subcutaneous emphysema, expanding and/or pulsatile hematoma, or brisk bleeding from the wound. All are overt findings suggestive of a major vascular or aero-digestive tract injury. Diagnostic studies are not essential for these presentations. Optimal airway management is always the first priority.

| Hard Signs | Soft Signs |

|---|---|

| Active bleeding | Dysphagia |

| Expanding or pulsatile hematoma | Voice change |

| Subcutaneous emphysema or air bubbling from wound | Hemoptysis |

| Wide mediastinum |

Without the “hard signs” of injury and, consequently, a need for immediate surgical intervention, a more selective or expectant approach can be initiated. The armamentarium of this selective approach include esophagoscopy, esophagography, laryngoscopy/tracheoscopy, arteriography, or Doppler ultrasonography. Although subtle findings (so-called “soft signs”—see Table 1) such as difficulty speaking or change in voice tone could prompt such a selective evaluation, the major controversy centers around whether patients with zone II injury and no “hard findings” should undergo selective management or just observation (expectant management).

AERO-DIGESTIVE INJURY

Simultaneous injuries of the airway and digestive tract are not uncommon due to the close proximity of the trachea and esophagus in the neck. According to Asensio and associates,2 aero-digestive tract injuries are seen in 10% of penetrating injuries. As highlighted previously, optimal airway management is the top priority.

In a patient who requires urgent airway management, the translaryngeal endotracheal approach is still the best option, particularly when it is performed by skilled practitioners.3 The role of the surgical airway should always be considered when approaching any patient who might have a difficult airway for conventional management. However, someone who is an expert with airway management should make an attempt at rapid translaryngeal endotracheal intubation. The surgical airway of choice in a true emergency setting is a cricothyroidotomy. A tracheostomy should only be considered in the adult when there is an urgent need for an airway in a patient who you suspect might have a partial laryngo-tracheal separation. Even in that setting, an attempt should be made, if possible, by an airway expert to perform a careful translaryngeal endotracheal intubation (Figure 3).

After achieving airway control, and if a selective management approach is chosen, the available modalities include flexible fiber-optic laryngoscopy, flexible esophagoscopy, flexible bronchoscopy and contrast esophagography. Using a water-soluble contrast agent and multiple views of the esophagus, extravasation can be safely excluded. The 85% sensitivity and specificity of this study can be increased to near 100% by the addition of esophagoscopy.6 With increased experience with flexible fiber-optic scopes and enhanced technology, dependence on the use of contrast studies has lessened. Visualization of the proximal 3–5 cm of the cervical esophagus immediately inferior to the cricopharyngeal constrictor is critical for this area can be easily missed during scope insertion and withdrawal. This area has to be specifically inspected.

For suspected laryngeal injuries, fiber-optic endoscopy is the diagnostic procedure of choice and can be combined with surgical exploration depending on the preference of the evaluating team and the suspicion for more severe injury. Laryngeal injury, including the thyroid cartilage, vocal cords, and the arytenoid processes, may require specialized reconstruction. The grading system (Table 2) advocated by Bent et al.5 details their retrospective experience over an 18-year period with laryngeal injuries. The emphasis is on securing an adequate airway and addressing all associated life-threatening injuries. With laryngeal injuries, airway control is best obtained by performing a tracheostomy. Treatment delay in laryngeal injuries beyond 48 hours can lead to inferior results. However, the delay often reflects the fact that the patient is severely injured and is unable to undergo definitive management. Mucosal coaptation and fracture reduction should be performed at the time of initial exploration.

| Group 1 | Minor endolaryngeal hematoma or laceration without detectable fracture |

| Group 2 | Edema, hematoma, minor mucosal disruption without exposed cartilage, nondisplaced fractures noted on computed tomography scan |

| Group 3 | Massive edema, mucosal tears, exposed cartilage, cord immobility, displaced fractures |

| Group 4 | Same as group 3 with more than two fracture lines or massive trauma to laryngeal mucosa |

| Group 5 | Complete laryngotracheal separation |

Source: Bent JP, Silver JR, Porubsky ES: Acute laryngeal trauma: a review of 77 patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 109:441–449, 1993.

Injury to the cervical esophagus can be difficult to diagnose and result in the development of a fulminant mediastinitis. Weigelt and associates6 reported only 7 of 10 injured patients with signs or symptoms of the esophageal injury. The authors noted that there is a false-negative rate of approximately 20% for either endoscopy or esophagography. When the two procedures were combined in evaluation, the false-negative rate decreased to 0%. Armstrong et al.7 reported a retrospective series of 23 patients with penetrating cervical esophageal injury. Contrast esophograms were only 62% sensitive, while rigid esophagoscopy was 100% sensitive. With advanced fiber-optic technology and greater operative experience, flexible endoscopy has essentially supplanted rigid esophagoscopy.

Injury to the pharynx, often subtle, requires simple primary repair and drainage.

VASCULAR INJURY IN THE NECK

In the early 20th century during U.S. military campaigns, major vascular injuries of the neck had very poor outcomes. A 30% neurologic deficit rate was reported after World War I when carotid injuries were treated by ligation.8 It was not until the 1950s and the military experience in Korea with vascular repair that carotid injury repairs became popular. The superior results were quickly appreciated, and a more aggressive management approach focusing on diagnosis and repair of vascular injuries was established.9 The first civilian report of carotid injuries appeared in 1956 when Fogelman and Stewart10 concluded that operative intervention was necessary and that mortality increased the longer surgery was delayed. This report was the basis for mandatory exploration of the neck as the standard of care for the next two decades.

Reports challenging the mandatory exploration for penetrating central neck injuries began being widely published in the mid-70s. Sheely and colleagues11 reported a series of 632 cases of penetrating neck injuries that still supported mandatory exploration but acknowledged that selected patients might be observed safely, provided they are treated by experienced personnel. Contrary opinion was presented by Saletta et al.,12 who reported a series of 246 patients that underwent mandatory neck exploration. While the negative exploration rate was high at 63%, morbidity was low and there was no mortality. Although they had negative clinical evaluations, 13 patients had findings at exploration of major injury. Mandatory exploration was thought to be justified. Concurring with this logic, Bishara et al.13 reported a series where 53% of the patients underwent mandatory exploration and had normal operative findings. However, 23% of the patients had injuries that were not suspected on preoperative clinical evaluation. These were most often isolated venous injuries or isolated pharyngoesophageal injuries. Surgical exploration for a zone II injury was felt to be safe and appropriate. Nevertheless, the high negative exploration rates noted with mandatory neck exploration prompted several institutions to question this approach. Elerding14 and coworkers reported a series with a 56% negative exploration rate on the basis of a mandatory exploration policy. All the patients with injuries were noted to have clinical signs suggestive of injury preoperatively. Selective exploration was felt to be a legitimate option in the evaluation and management of these patients.

Jurkovich et al.15 reported that the diagnostic yield of combined angiographic and fluorographic studies of the vascular and aerodigestive anatomy was 23%. Only 9% of patients benefited from such studies. Using the zone of injury to determine the management approach, Jurkovich advocated aggressive use of angiography, chest radiographs and esophagography for zone I injury and angiography for zone III. It was emphasized that zone II injuries could be safely observed, if the patients were asymptomatic. Additional support for a more selective approach to the management of these injuries was published by Obeid and associates16 who, in a retrospective review, concluded that mandatory exploration should be supplanted by a selective management policy. The rationale behind this support was predicated on several findings, including the fact that missed injuries still occurred with mandatory explorations and that there was morbidity associated with negative exploration and considerable number of hospital days. Obeid et al.16 felt that patients with “hard signs” of injury needed operative intervention, while those patients with negative physical examinations could be observed. Patients with equivocal findings on physical examination or with changing findings needed ancillary diagnostic studies to determine whether any clinically significant injuries exist. Additional support for a selective exploration policy was published by Belinke et al.17 In this study, 44 patients were treated with a selective exploration policy, based on physical findings. Twenty-two patients underwent immediate exploration with a negative exploration rate of 23%. In the group of patients observed, there were no delayed operations or complications. If all the patients had been subject to immediate exploration, the negative exploration rate would have been 60%, prompting the authors to advocate a selective approach to penetrating zone II injuries.

Metzdorff and colleagues,18 who also endorsed a selective management theme, reported 83 patients with a 56% negative exploration rate. When clinical signs of injury were noted preoperatively, an injury was found in 82% of the patients. If the preoperative physical examination was negative, there were no injuries found in 80% of the patients.

In 1987, Meyer and associates19 reported a prospective trial of 120 patients with penetrating neck wounds. Seven patients underwent emergency exploration for hemorrhage. The remaining patients underwent arteriography, upper aero-digestive endoscopy, and esophagography plus surgical exploration. Five patients were found to have six major vascular injuries that were not expected preoperatively. The authors concluded that selective management missed too many major vascular injuries and that mandatory exploration was a more prudent approach.

Wood and colleagues20 advocated selective management based on presenting physical findings. Equivocal findings required diagnostic studies to clarify the need for surgical exploration. In a similar argument, Narrod and Moore21 confirmed the safety and efficacy of selective management of these patients. Mansour et al.22 endorsed selective nonoperative management when it was determined that only one patient in a cohort of 119 patients required a delayed operation for an occult injury.

Beitsch et al.23 reported a retrospective review of penetrating wounds to the neck. A negative physical examination ruled out 99% of the vascular injuries. Seventy-one angiograms were performed. Only one patient required operative repair. In the light of a normal physical examination, mandatory exploration and the role of angiographic evaluation were questioned.

Scalfani and colleagues24 reported on a study of proximity angiograms, and noted that physical examination had a sensitivity of 61% and a specificity of 80%. The authors argued that not incorporating proximity angiography in the evaluation of penetrating neck injuries was premature. However, Menawat et al.25 reported that in a series of 110 patients with penetrating neck injuries, only one patient had an injury not predicted by physical examination findings. Nine arterial injuries were treated nonoperatively without sequelae. Atteberry and coworkers26 reported on a prospective study of 66 patients which highlighted that in the absence of definitive or “hard signs” of vascular injury, these patients could be safely watched. Sekharan et al.27 reported a missed injury rate of 0.7% with physical examination alone. Also, Jarvik et al.28 reported that physical examination was sensitive and specific enough for detecting clinically significant vascular injuries. Physical examination had a sensitivity of 93.7%. Azuaje and associates’29 series of penetrating neck injuries demonstrated a sensitivity and negative predictive value of 100% for physical examination in detecting surgically significant vascular injuries. When considering injuries detected by angiography, physical examination showed a sensitivity of 93% and a negative predictive value of 97%. No patient in this series with a negative physical examination required a vascular repair, regardless of the zone of injury.

Referring specifically to zone III wounds, Ferguson et al.30 reports a series of 72 patients with penetrating wounds. The absence of “hard signs” reliably excluded surgically significant injuries. Sixty percent of the patients with “hard signs” of injury were explored. Only one patient in this group had no identifiable injury. The remainder of the patients with “hard signs” of injury underwent emergent angiography with endovascular angiographic treatment. The authors recommended that zone III injuries with “hard signs” of vascular injury should undergo angiography, as they may be amenable to endovascular intervention.

A variety of complementary diagnostic modalities have been proposed as adjuncts to the evaluation of penetrating neck injuries. Ginzburg et al.31 demonstrated, in a prospective double-blind evaluation of angiography and duplex scanning in stable patients with zone I, II, or III penetrating wounds, that duplex scans had 100% sensitivity and 85% specificity.

Newer imaging modalities have emerged. Munera and colleagues32 prospectively studied 60 patients, and reported that helical CT had a sensitivity of 90%, a specificity of 100%, a positive predictive value of 100%, and a negative predictive value of 98%. The authors concluded that helical CT was an excellent diagnostic study in the evaluation of neck injuries. Also, Mazolewski et al.33 performed a prospective evaluation of 14 stable patients with penetrating zone II injuries. All patients underwent thorough physical examination, infusion CT scan, and operative exploration. Three of the 14 patients had five injuries. Those patients had a high probability for injury based on the CT scan findings. Although a small sample size, results indicated that the CT scan had a sensitivity of 100%, specificity of 91%, positive predictive value of 75%, and negative predictive value of 100%. The authors felt that the CT scan should play a pivotal role in the evaluation of neck injuries. Gracias and coworkers34 conducted a retrospective series of 23 patients evaluated by CT scan for penetrating neck trauma that spanned all three zones. All the patients lacked “hard signs” of vascular or aero-digestive injury. Thirteen patients had the trajectory of injury remote from important structures identified and no further evaluation carried out. There were no adverse events. Gonzalez et al.35 reported on a prospective study of computed tomography in patients with zone II penetrating wounds without “hard signs” of injury necessitating immediate exploration. The authors concluded that CT added little to the information obtained by physical examination with zone II injuries.

Hollingsworth et al.36 conducted a meta-analysis of computed tomographic angiography (CTA) for detection of carotid and vertebral lesions of either atherosclerotic or traumatic origin. It was concluded that there were insufficient high-quality data to comment on the sensitivity or specificity of CTA for trauma.

Woo and colleagues37 studied patients with zone II penetrating wounds who underwent CTA as a diagnostic test. They reported that with increase utilization of CTA and enhanced staff experience, there was an associated decrease in the number of negative neck explorations. The authors highlighted that with this imaging, wound tracts could be visualized. This could assist in determining if other diagnostic studies would be needed. For example, the CT could show that the injury tract was away from any major structure thus obviating any further investigation. Alternatively, an injury may be demonstrated and surgical exploration or conventional angiography for endovascular intervention could be performed. Finally, an indeterminate study may prompt other investigations depending on the finding in question.

Angiography has been advocated for zone I injuries at the base of the neck because injury in the thoracic outlet would be difficult to diagnose and control. Eddy et al.38 conducted a multi-institutional retrospective study surveying patients over a 10-year period. A total of 138 patients were studied and 28 arterial injuries were found. However, the group concluded that in the presence of a normal physical examination and a normal chest radiograph, angiographic study may not be needed.

Gasparri and associates39 confirmed this finding after conducting a retrospective review of 100 patients. All patients with “hard signs” of vascular injury were taken for expeditious surgical exploration. Eighty-one patients without “hard signs” of injury underwent angiography, and 11 occult injuries were discovered. When a normal physical examination and a normal chest radiograph are combined, they have a sensitivity of 100%, a specificity of 80%, a positive predictive value of 40%, and a negative predictive value of 100%. The group concluded that proximity alone does not mandate angiography.

A prospective trial by Demetriades et al.40 evaluating the role of physical examination in penetrating neck wounds demonstrated that the lack of hard clinical signs of vascular or aero-digestive injury had a negative predictive value of 100% and reliably excluded all such wounds needing operative repair. The algorithm used by this group specifically looked for physical examination information regarding vascular and aero-digestive injury. Asymptomatic patients were observed safely.

Our own approach is outlined in the algorithm in Figure 4. Patients presenting with “hard signs” of vascular or aero-digestive injury go immediately to the operating room for neck exploration. The surgical approach is at the discretion of the attending surgeon. Patients without “hard signs” are observed. Recently, we have incorporated helical CT to evaluate such patients. If the wound tract is obviously away from major structures of concern, no specific therapy is initiated. Our results do not support that CT has offered a substantial advantage over astute physical examination at this time.

TREATMENT OF CAROTID ARTERY INJURIES

The surgical approach to the cervical vasculature is predicated on the zone of injury. Zone II injuries are best approached via an incision along the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle with the head turned to the opposite side. Placement of a towel roll under the patient’s shoulders is very helpful. Dissection along this line will encounter the common facial vein, which can be sacrificed, and will allow complete visualization of the common carotid artery, the carotid bulb, the proximal internal carotid and the external carotid arteries, and the internal jugular vein. Carotid arterial injuries are best treated by surgical repair. The use of a vein patch taken from adjacent facial vein or Gortex™ is an alternative to direct suture repair. Shunts are not routinely used in these circumstances. When to repair versus ligate is complicated by the poor ability to discriminate between severe ischemia and evolving infarction. Patients with fixed neurologic deficits do poorly with revascularization. Injuries distal in the common carotid may require special maneuvers to gain access for repair. Disarticulation of the temporomandibular joint allowing forward displacement of the mandible will allow access to the internal carotid cephalad to the angle of the mandible. The skull base is not surgically accessible and may require interventional techniques to control. Injuries to the proximal internal carotid not amenable to repair may benefit from ligation of the proximal external carotid and utilization of it as a conduit for restoration of internal carotid flow. Pro-grade flow in the carotid at the time of surgical exploration is a good indication for repair. In the absence of pro-grade flow ligation may be preferable. Ligation of the injured carotid should be reserved only for those patients with devastating neurologic injuries. Liekweg and Greenfield’s41 review of the literature demonstrated less morbidity and mortality in the revascularization group compared to the ligation group. Unger et al.42 and Brown et al.43 in separate reports confirm this recommendation for revascularization over ligation.

An extended collar incision, as used for thyroid or parathyroid procedures, can be used for bilateral neck explorations. Transcervical gunshot wounds with the potential for bilateral vascular injury might be better approached through this incision as bilateral control is easy to obtain from one position. This incision may need to be moved cephalad in the neck to facilitate exposure on occasions.

1 Basmajian JV, editor. Grant’s Method of Anatomy, 9th ed., Philadelphia: Williams and Wilkins, 1975.

2 Asensio JA, Valenziano CP, Falcone RE, et al. Management of penetrating neck injuries: the controversy surrounding zone II injuries. Surg Clin North Am. 1991;71:267-296.

3 Mandavia DP, Qualls S, Rokos I. Emergency airway management in penetrating neck injury. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;35(3):221-225.

4 Shearer VA, Giesecke AH. Airway management for patients with penetrating neck trauma: a retrospective study. Anesth Analg. 1993;77:1135-1138.

5 Bent JP, Silver JR, Porubsky ES. Acute laryngeal trauma: a review of 77 patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1993;109:441-449.

6 Weigelt JA, Thal ER, Snyder WH, et al. Diagnosis of penetrating cervical esophageal injuries. Am J Surg. 1987;154:619.

7 Armstrong WB, Detar TR, Stanley RB. Diagnosis and management of external penetrating cervical esophageal injuries. Ann Otol Rhino Laryngol. 1994;103(11):863-871.

8 GH Makins: Injuries to the blood vessels. In: Official History of the Great War Medical Services. Surgery of the War. London, 1922, pp. 170–296

9 Hughes CW. Acute vascular trauma in Korean war casualties: an analysis of 180 cases. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1954;99:91-100.

10 Fogelman MJ, Stewart RD. Penetrating wounds of the neck. Am J Surg. 1956;91:581-596.

11 Sheely CH2nd, Mattox KL, Reul GJJr, et al. Current concepts in the management of penetrating neck trauma. J Trauma. 1975;15(10):895-900.

12 Saletta JD, Lowe RJ, Lim LT, et al. Penetrating trauma of the neck. J Trauma. 1976;16(7):579-587.

13 Bishara RA, Pasch AR, Douglas DD, et al. The necessity of mandatory exploration of penetrating zone II. Neck Inj Surg. 1986;100(4):655-660.

14 Elerding SC, Manart FD, Moore EE. A reappraisal of penetrating neck injury management. J Trauma. 1980;20(8):695-697.

15 Jurkovich GJ, Zingarelli W, Wallace J, et al. Penetrating neck trauma: diagnostic studies in the asymptomatic patient. J Trauma. 1985;25(9):819-822.

16 Obeid FN, Haddad GS, Horst HM, et al. A critical reappraisal of a mandatory exploration policy for penetrating wounds of the neck. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1985;160(6):517-522.

17 Belinke SA, Russell JC, Dasilva J, et al. Management of penetrating neck injuries. J Trauma. 1983;23(3):235-237.

18 Metzdorff MT, Lowe DK. Operation or observation for penetrating neck wounds? A retrospective analysis. Am J Surg. 1984;147(5):646-649.

19 Meyer JP, Barnett JA, Schuler JJ, et al. Mandatory versus selective exploration for penetrating neck trauma: a prospective assessment. Arch Surg. 1987;122(5):592-597.

20 Wood J, Fabian TC, Mangiante EC. Penetrating neck injuries: recommendations for selective management. J Trauma. 1989;29(5):602-605.

21 Narrod JA, Moore EE. Selective management of penetrating neck injuries: a prospective study. Arch Surg. 1984;119(5):5748.

22 Mansour MA, Moore EE, Moore FA, et al. Validating the selective management of penetrating neck wounds. Am J Surg. 1991;162(6):517-520.

23 Beitsch P, Weigelt JA, Flynn E. Physical examination and arteriography in patients with penetrating zone II neck wounds. Arch Surg. 1994;129(6):577-581.

24 Scalfani SJ, Cavaliere G, Atwew N, et al. The role of angiography in penetrating neck trauma. J Trauma. 1991;31(4):557-562.

25 Menawat SS, Dennis JW, Laneve LM. Are arteriograms necessary in penetrating zone II neck injuries? J Vasc Surg. 1992;16(3):397-400.

26 Atteberry LR, Dennis JW, Menawat SS, et al. Physical examination alone is safe and accurate for evaluation of penetrating zone II neck trauma. J Am Coll Surg. 1994;179(6):657-662.

27 Sekharan J, Dennis W, Veldenz C, et al. Continued experience with physical examination alone for the evaluation and management of penetrating zone 2 neck injuries: results of 145 cases. J Vasc Surg. 2000;32(3):483-489.

28 Jarvik JG, Philips GR3rd, Schwab CW, et al. Penetrating neck trauma: sensitivity of clinical examination and cost effectiveness of angiography. Am J Neuroradiol. 1995;16(4):647-654.

29 Azuaje RE, Jacobson LE, Glover J, et al. Reliability of physical examination as a predictor of vascular injury after penetrating neck injury. Am Surg. 2003;69(9):804-807.

30 Ferguson E, Dennis JW, Frykberg ER. Redefining the role of arterial imaging in the management of penetrating zone 3 neck injuries. Vascular. 2005;13(3):158-163.

31 Ginzburg E, Montalvo B, LeBlanc S, et al. The use of duplex ultrasonography in penetrating neck trauma. Arch Surg. 1996;131(7):691-693.

32 Munera F, Soto JA, Palacio D, et al. Diagnosis of arterial injuries caused by penetrating trauma to the neck: comparison of helical CT angiography and conventional angiography. Radiology. 2000;216(2):356-362.

33 Mazolewski PJ, Curry JD, Browder T, et al. Computer tomographic scanning can be used for surgical decision making in zone II penetrating neck injuries. J Trauma. 2001;51(2):315-319.

34 Gracias VH, Reilly PM, Philpot J, et al. Computed tomography in the evaluation of penetrating neck trauma. Arch Surg. 2001;136:1231-1235.

35 Gonzalez RP, Falimirski M, Holevar MR, et al. Penetrating zone II neck injury: does dynamic computed tomographic scan contribute to the diagnostic sensitivity of physical examination for surgically significant lesions? A prospective blind study. J Trauma. 2003;54(1):61-64.

36 Hollingworth W, Nathens AB, Kanne JP, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of computed tomographic angiography for traumatic or atherosclerotic lesions of the carotid and vertebral arteries: a systematic review. Eur J Radiol. 2003;48(1):88-102.

37 Woo K, Magner DP, Wilson MT, et al. CT angiography in penetrating neck trauma reduces the need for operative neck exploration. Am Surg. 2005;71(9):754-758.

38 Eddy VA. Is routine arteriography mandatory for penetrating injury to zone I of the neck? Penetrating Injury Study Group. J Trauma. 2000;48(2):208-213.

39 Gasparri MG, Lorelli DR, Kralovich KA, et al. Physical examination plus chest radiography in penetrating peri-clavicular trauma: the appropriate trigger for angiography. J Trauma. 2000;49(6):1029-1033.

40 Demetriades D, Theodorou D, Cornwell E, et al. Evaluation of penetrating injuries of the neck: prospective study of 223 patients. World J Surg. 1997;21:41-48.

41 Liekweg WG, Greenfield LJ. Management of penetrating carotid arterial injury. Ann Surg. 1978;188:587.

42 Unger SW, Tucker W, et al. Carotid arterial trauma. Surgery. 1980;87:477.

43 Brown JM, Graham JM, Feliciano DV. Carotid artery injury. Am J Surg. 1982;144:748.