PELVIS

Précis of the Pelvis Assessment*

Resisted isometric movements (supine)

Functional test of supine active straight leg raise test

Sacroiliac rocking (knee-to-shoulder) test

Passive movements (side lying)

Reflexes and cutaneous distribution (supine, then prone)

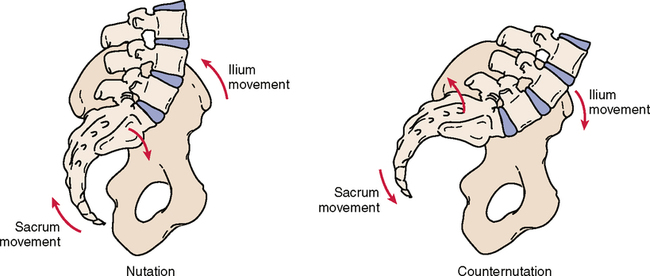

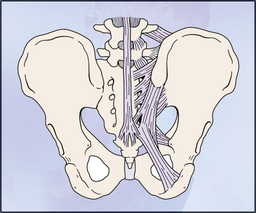

Cephalad movement of the sacrum with caudal movement of the ilium

Cephalad movement of the ilium with caudal movement of the sacrum

*The examination is shown in an order that limits the amount of moving or position changing the patient must do, yet ensures that all necessary structures are tested.

SELECTED MOVEMENTS

NUTATION AND COUNTERNUTATION1–4 ![]()

• During extension, or backward bending, of the trunk, the innominate bones (i.e., the pelvic girdle) as a whole unit rotate posteriorly (nutation) on the femoral heads bilaterally. If one leg is actively flexed at the hip, the innominate on that side unilaterally rotates posteriorly.

• During the posterior rotation of the innominate bones, the innominate slides anteriorly along the long arm of the sacral joint and superiorly up the short arm of the sacral joint. This movement is the same as sacral nutation. With backward bending, the two PSISs move inferiorly an equal amount.

COMMON STRESS TESTS (PASSIVE MOVEMENTS)

IPSILATERAL PRONE KINETIC TEST ![]()

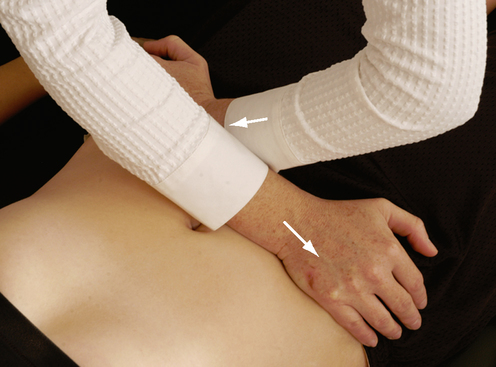

PASSIVE EXTENSION AND MEDIAL ROTATION OF THE ILIUM ON THE SACRUM1,5 ![]()

PASSIVE FLEXION AND LATERAL ROTATION OF THE ILIUM ON THE SACRUM1,5 ![]()

GAPPING (TRANSVERSE ANTERIOR STRESS) TEST1,6,7 ![]()

• Care must be taken in performing this test. Pushing against the ASISs can elicit pain, because the soft tissue is compressed between the examiner’s hands and the patient’s pelvis. If this is the case, the patient can be instructed to place his or her hands on each ASIS. The examiner then can push through the patient’s hands.

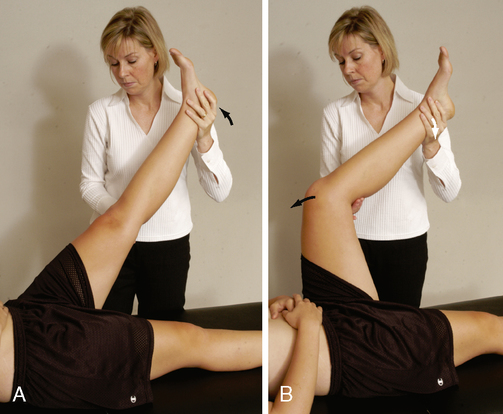

SACROILIAC ROCKING (KNEE TO SHOULDER) TEST1,8 ![]()

• This test is also called the sacrotuberous ligament stress test.

• For proper performance of this test, both the hip and the knee must demonstrate no pathological conditions and must have full range of motion.

• Care must be taken when performing this test, because it puts a great deal of stress on the hip and sacroiliac joints. If a longitudinal force is applied through the hip in a slow, steady manner (for 15 to 20 seconds) in an oblique and lateral direction, further stress is applied to the sacrotuberous ligament.

SPECIAL TEST FOR NEUROLOGICAL INVOLVEMENT

PRONE KNEE BENDING (NACHLAS) TEST9–11 ![]()

INDICATIONS OF A POSITIVE TEST

• If pain is felt in the front of the thigh before full range is reached, the problem is in the rectus femoris muscle.

• If pain is felt in the lumbar spine, the problem is in the lumbar spine, usually the L3 nerve root, especially if radicular symptoms are noted.

• If the problem is a hypomobile sacroiliac joint, the ipsilateral pelvic rim (ASIS) will rotate forward, usually before the knee reaches 90º of flexion.

• This test also stretches the femoral nerve. Pain in the anterior thigh may indicate tight quadriceps muscles or stretching of the femoral nerve. A careful history and pain differentiation help delineate the problem.

• If the examiner is unable to flex the patient’s knee past 90° because of a pathological condition in the knee, the test may be performed by passive extension of the hip while the knee is flexed as much as possible.

• If the rectus femoris is tight, the examiner should remember that taking the patient’s heel to the buttock may cause anterior torsion to the ilium, which could lead to sacroiliac or lumbar pain.

• The test may be modified to stress different peripheral nerves (see Table 8-8).

SPECIAL TESTS FOR SACROILIAC JOINT DYSFUNCTION6,7

Relevant Special Tests

Gillet’s test (sacral fixation test)

Functional test of supine active straight leg raise

Functional test of prone active straight leg raise

Prone knee bending (Nachlas) test

Relevant Signs and Symptoms

• The patient complains of pain in the region of the sacral sulcus, just medial to the posterior superior iliac spine. The pain may travel distally into the buttock and posterior thigh.

• Symptoms typically do not extend to or beyond the knee.

• Pain of sacroiliac joint origin does not generally refer proximally to the lumbar spine.

Mechanism of Injury

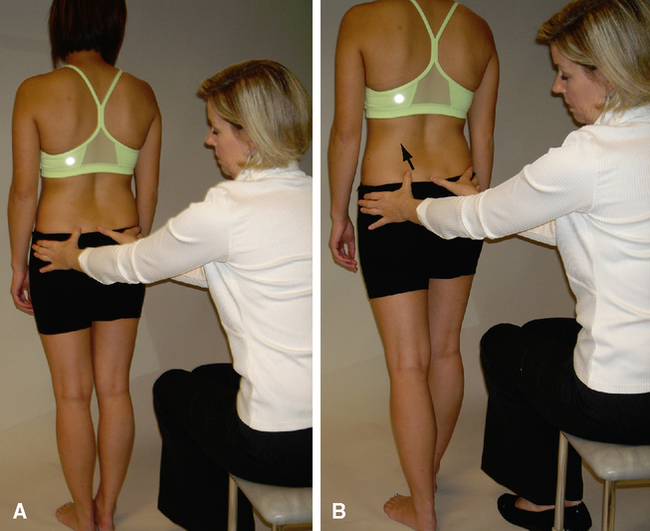

GILLET’S TEST (SACRAL FIXATION TEST)12–15 ![]()

• This test is also called the ipsilateral posterior rotation test.

• Jackson15 has suggested a modification of the test. After completing Gillet’s test, the examiner palpates the same PSIS and sacrum and asks the patient to do a repeat Gillet’s test using the other leg; this causes the opposite innominate bone to rotate posteriorly. As the patient flexes the hip and knee, the lumbar spine begins to flex, causing the sacrum to move inferiorly; as a result, the test innominate (the side opposite the leg being flexed) rotates anteriorly.

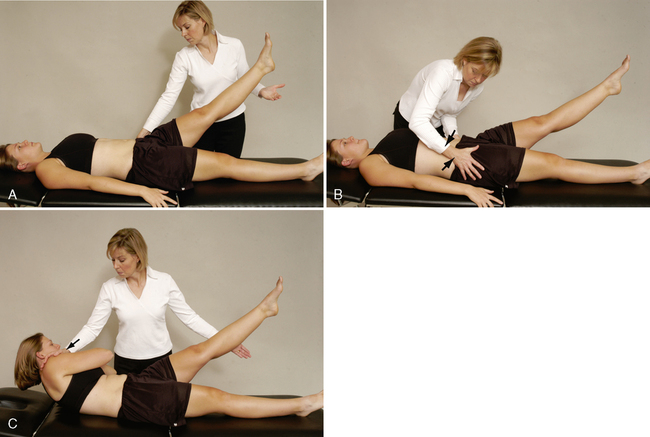

FUNCTIONAL TEST OF SUPINE ACTIVE STRAIGHT LEG RAISE1,16–18 ![]()

• A modification tests force closure at the sacroiliac joints. The patient is asked to flex and rotate the trunk toward the side on which the straight leg raise (SLR) was actively being performed, and the examiner resists the trunk motion. The two sides are compared for any difference.

• Force closure tests the muscles’ ability to stabilize the sacroiliac joints during movement.

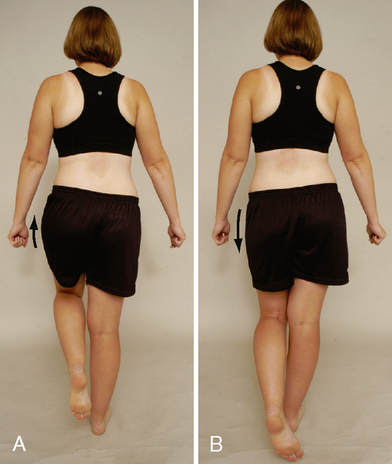

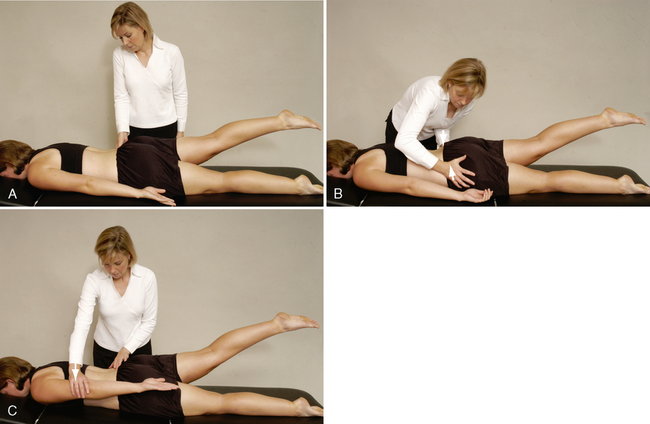

FUNCTIONAL TEST OF PRONE ACTIVE STRAIGHT LEG RAISE1 ![]()

SPECIAL TESTS FOR LEG LENGTH

Relevant Special Tests

Epidemiology and Demographics

Freiberg19 studied patients with low back pain and discovered that patients with a leg length discrepancy greater than 15 mm were five times more likely to experience low back pain. Hip and sciatic pain occurred in the longer leg 78% of the time. In patients with leg length discrepancies greater than 3 cm, an asymmetrical lateral side bend of the spine occurs on the side of the longer leg; this results in abnormal loading mechanics of the spine. Leg length discrepancies of this magnitude are present in 40% of the general population.20

ten Brinke et al.20 reported that in 64 (62%) of 104 patients with a leg length discrepancy of 1 mm or greater, the back pain radiated into the shorter leg.

Relevant Signs and Symptoms

• Leg length differences themselves are not usually painful.

• Difference is clinically relevant as a contributing cause of symptoms and pathological conditions in other regions, such as the lumbar spine, pelvis, sacroiliac joint, or lower extremity.

• Objective examination of any of these regions should include an examination of leg length.

Mechanism of Injury

INDICATIONS OF A POSITIVE TEST

If the asymmetry has been corrected by “correcting” the position of the limb, the leg is structurally normal (i.e., the bones have proper length) but abnormal joint mechanics (i.e., a functional deficit) are producing a functional leg length difference (Table 9-1). Therefore, if the asymmetry is corrected by proper positioning, the test result is positive for a functional leg length difference.

Table 9-1

Functional Limb Length Difference

| Joint | Functional Lengthening | Functional Shortening |

| Foot | Supination | Pronation |

| Knee | Extension | Flexion |

| Hip | Lowering | Lifting |

| Extension | Flexion | |

| Lateral rotation | Medial rotation | |

| Sacroiliac | Anterior rotation | Posterior rotation |

Modified from Wallace LA: Lower quarter pain: mechanical evaluation and treatment. In Grieve GP (ed): Modern manual therapy of the vertebral column, p 467, Edinburgh, 1986, Churchill Livingstone.

OTHER SPECIAL TESTS

• This test should always be performed on the unaffected side first so that the patient understands what to do.

• Although the examiner watches what happens on the nonstance side, it is the stance side that is being tested.

• The patient also may try to compensate by lateral flexing toward the stance leg. This position is taken so that the patient’s center of mass is placed over the stance limb. As a result, the demands on the gluteal muscle are less. This compensation should be corrected and the test repeated.

Related posts:

Orthopedic Physical Assessment Atlas and Video Selected Special