Pelvis

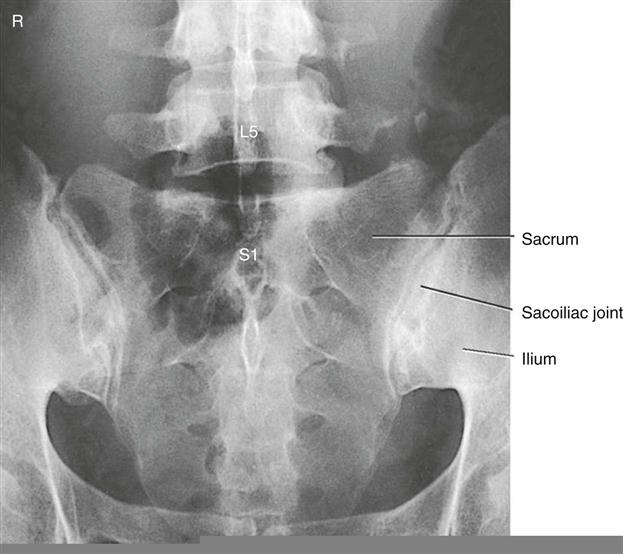

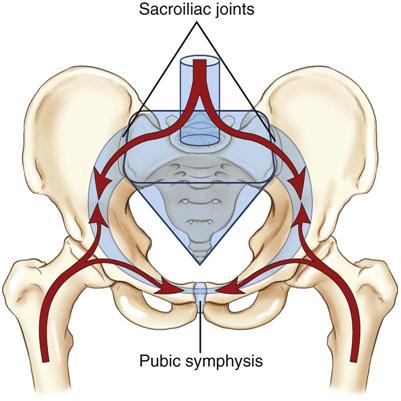

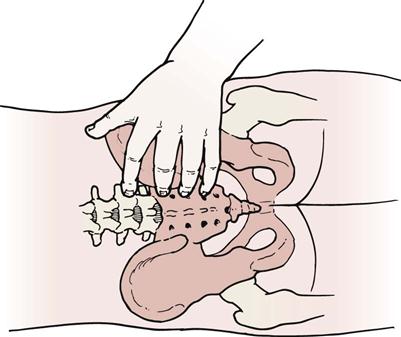

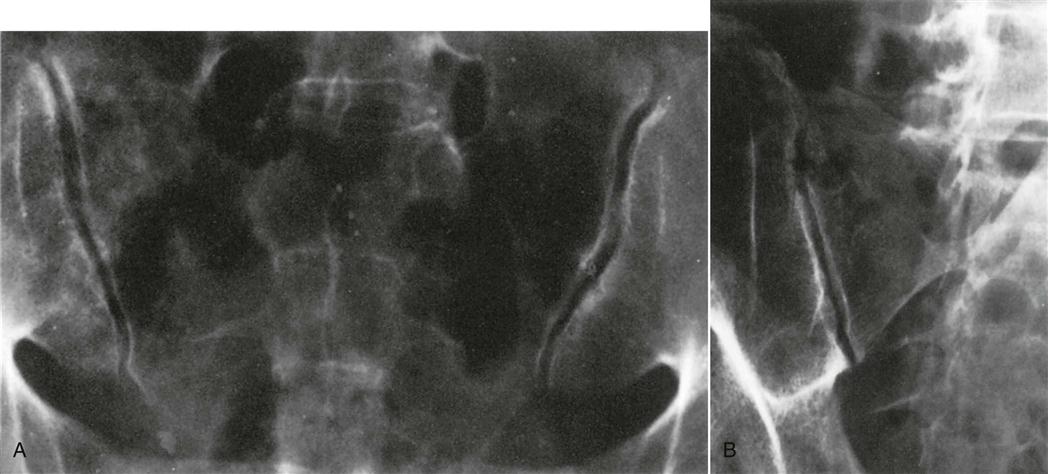

The sacroiliac joints form the “key” of the arch between the two pelvic bones; with the symphysis pubis, they help to transfer the weight from the spine to the lower limbs and provide elasticity to the pelvic ring (Figure 10-1). This triad of joints also acts as a buffer to decrease the force of jars and bumps to the spine and upper body caused by contact of the lower limbs with the ground. Because of this shock-absorbing function, the structure of the sacroiliac and symphysis pubis joints is different from that of most joints that are assessed. Assessment of the sacroiliac joints and symphysis pubis should be included in the examination of the lumbar spine and/or hips if there is no direct trauma to either one of these joints.1 Normally, a comprehensive examination of the sacroiliac joints is not made until examination of the lumbar spine and/or hip has been completed. If both of these joints are examined and the problem still appears to be present and remains undiagnosed, an examination of the pelvis should be initiated.

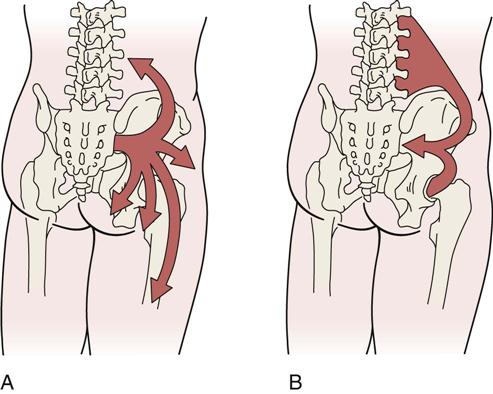

The arrows show the direction of body weight force as it is transferred between the pelvic ring, trunk, and femurs. The keystone of the pelvic ring is the sacrum, which is wedged between the two ilia and secured bilaterally by the sacroiliac joints. (From Neumann DA: Kinesiology of the musculoskeletal system, ed 2, St Louis, 2010, CV Mosby, p. 360. Redrawn after Kapandji IA: The physiology of joints, vol 3, New York, 1974, Churchill Livingstone.)

Applied Anatomy

The sacroiliac joints are part synovial joint and part syndesmosis. A syndesmosis is a type of fibrous joint in which the intervening fibrous connective tissue forms an interosseous membrane or ligament. The synovial portion of the joint is C-shaped, with the convex iliac surface of the C facing anteriorly and inferiorly. Kapandji2 states that the greater or the more acute the angle of the C, the more stable the joint and the less the likelihood of a lesion to the joint. The sacral surface is slightly concave.

The size, shape, and roughness of the articular surfaces of the sacrum vary greatly among individuals. In the child, these surfaces are smooth. In the adult, they become irregular depressions and elevations that fit into one another; by so doing, they restrict movement at the joint and add strength to the joint for transferring weight from the lower limb to the spine. The articular surface of the ilium is covered with fibrocartilage; the articular surface of the sacrum is covered with hyaline cartilage that is three times thicker than that of the ilium. In older persons, parts of the joint surfaces may be obliterated by adhesions.

Although the sacroiliac joints are relatively mobile in young people, they become progressively stiffer with age. In some cases, ankylosis results. The movements that occur in the sacroiliac and symphysis pubis joints are slight compared with the movements occurring in the spinal joints.

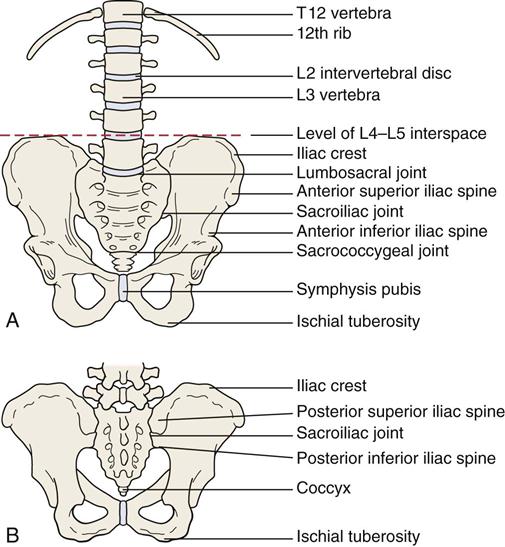

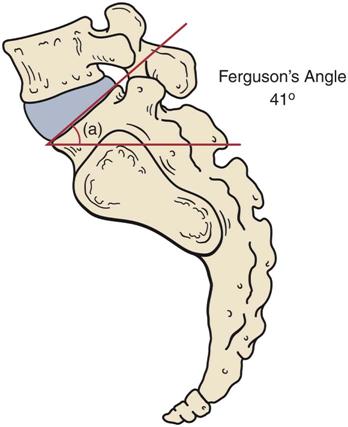

The sacroiliac joints are supported by several strong ligaments (Figure 10-2)—the long posterior sacroiliac ligaments that limit anterior pelvic rotation3 or sacral counternutation, the short posterior sacroiliac ligament that limits all pelvic and sacral movement, the posterior interosseous ligament that forms part of the sacroiliac articulation (the syndesmosis), and the anterior sacroiliac ligaments.4 The sacrotuberous ligament and sacrospinous ligament limit nutation and posterior innominate rotation and provides vertical stability.4 The iliolumbar ligament stabilizes L5 on the ilium.4

The sacroiliac joints and symphysis pubis have no muscles that control their movements directly, although muscles do provide pelvic stability. However, they are influenced by the action of the muscles moving the lumbar spine and hip, because many of these muscles attach to the sacrum and pelvis (Table 10-1).

TABLE 10-1

Muscles Attaching to the Pelvis

| Muscles | Nerve Root Derivation |

| Latissimus dorsi | Thoracodorsal (C6–C8) |

| Erector spinae | L1–L3 |

| Multifidus | L1–L5 |

| External oblique | T7–T12 |

| Internal oblique | T7–T12, L1 |

| Transverse abdominis | T7–T12, L1 |

| Rectus abdominis | T6–T12 |

| Pyramidalis | Subcostal (T12) |

| Quadratus lumborum | T12, L1–L4 |

| Psoas minor | L1 |

| Iliacus | Femoral (L2, L3) |

| Levator ani | S4, inferior rectal nerve/pudendal nerve |

| Sphincter ani externus | S2–S4 |

| Superficial transverse perineal ischiocavernous | S2–S4 |

| Coccygeus | S4, S5 |

| Gluteus maximus | Inferior gluteal (L5, S1, S2) |

| Gluteus medius | Superior gluteal (L5, S1) |

| Gluteus minimus | Superior gluteal (L5, S1) |

| Obturator internus | Nerve to obturator internus (L5, S1) |

| Obturator externus | Obturator (L3, L4) |

| Piriformis | L5, S1, S2 |

| Interior gemellus | Nerve to quadratus femoris (L5, S1) |

| Superior gemellus | Nerve to obturator internus (L5, S1) |

| Pectineus | Femoral (L2, L3) |

| Semimembranosus | Sciatic (L5, S1, S2) |

| Semitendinosus | Sciatic (L5, S1, S2) |

| Biceps femoris | Sciatic (L5, S1, S2) |

| Tensor fascia lata | Superior gluteal (L4, L5) |

| Sartorius | Femoral (L2, L3) |

| Rectus femoris | Femoral (L2–L4) |

| Gracilis | Obturator (L2, L3) |

| Adductor magnus | Obturator/sciatic (L2–L4) |

| Adductor longus | Obturator (L2–L4) |

| Adductor brevis | Obturator (L2–L4) |

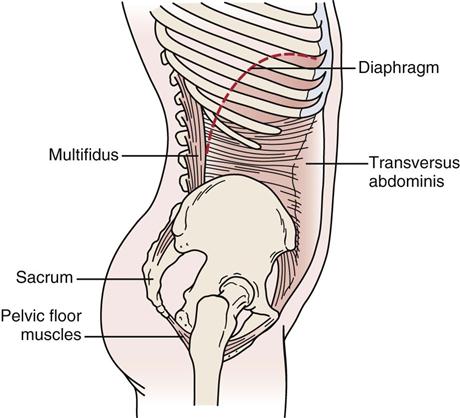

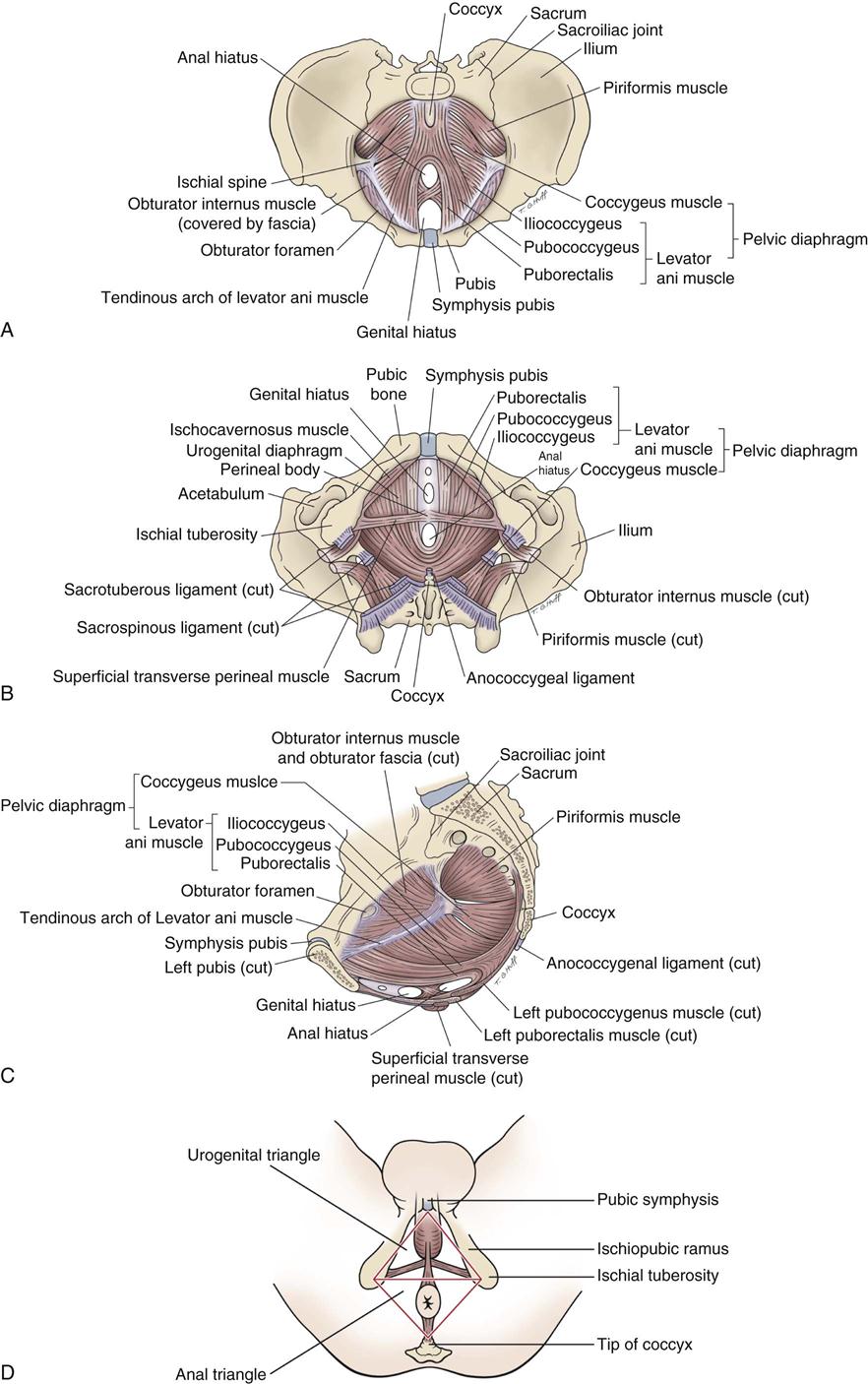

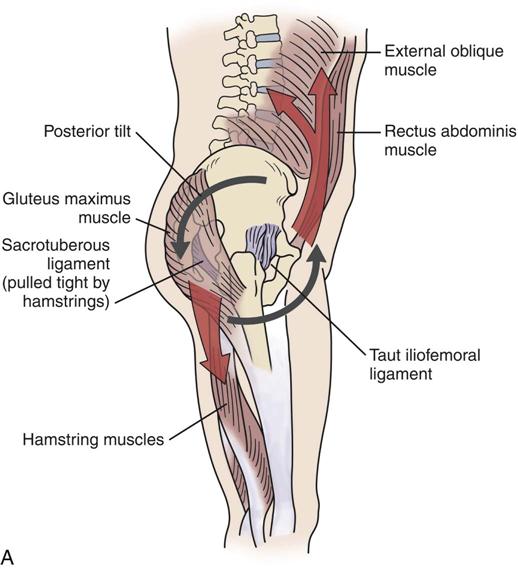

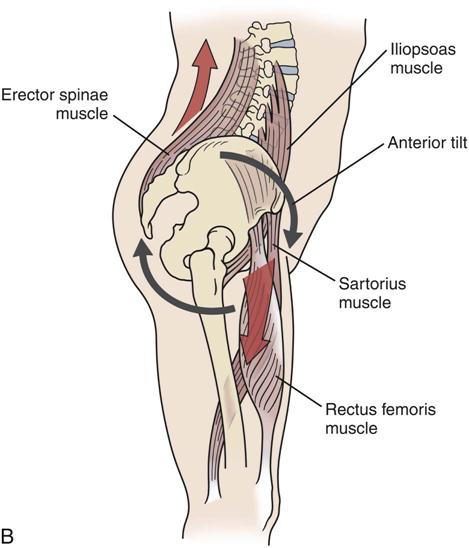

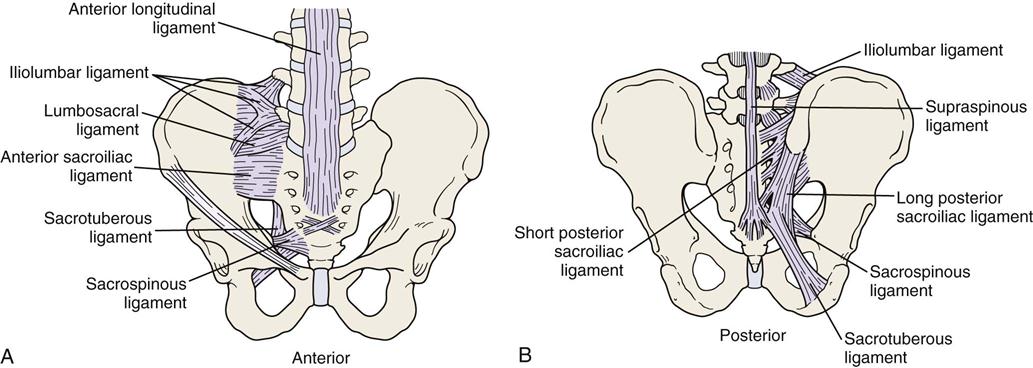

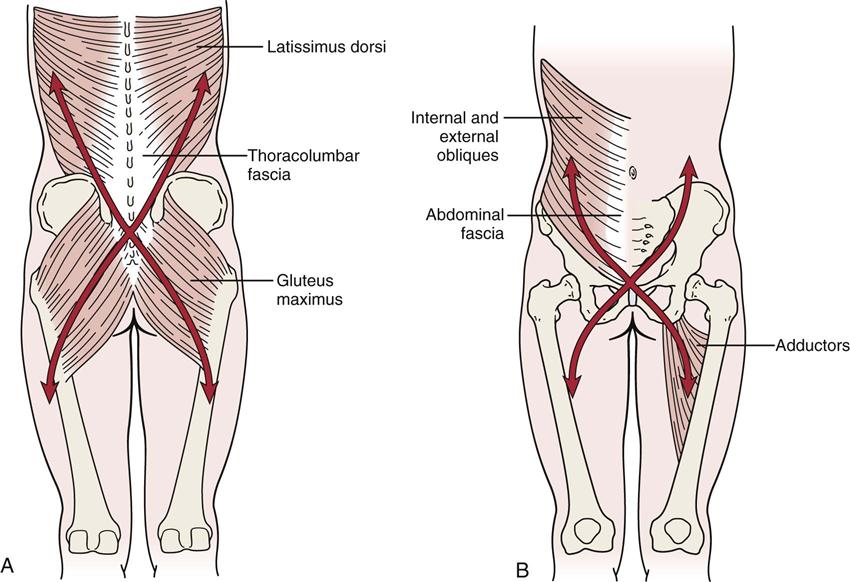

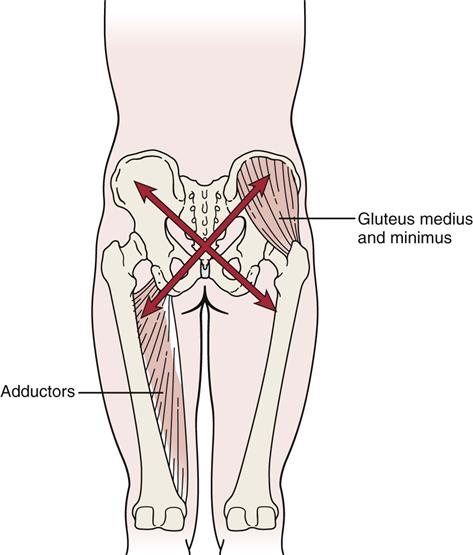

The muscles that support the pelvic girdle as well as the lumbar spine and hips can be divided into groups.5–7 The outer group consists of four groupings, which act primarily in crossing or oblique patterns of force couples to stabilize the pelvis. The deep posterior longitudinal system consists of the erector spinae, thoracolumbar fascia, and the hamstring muscles, along with the sacrotuberous ligament (Figure 10-3). The superficial posterior oblique system includes the latissimus dorsi, gluteus maximus, and the intervening thoracolumbar fascia (Figure 10-4, A). The anterior oblique system consists of the internal and external obliques, the contralateral adductors, and the abdominal fascia in between (Figure 10-4, B). The lateral system consists of gluteus medius and minimus and the contralateral adductors (Figure 10-5). The innermost muscle group consists of the multifidus, transverse abdominus, diaphragm (Figure 10-6), and pelvic floor muscles (Figure 10-7) that can play a role in stabilizing the pelvis and indirectly the lumbar spine. The anterior-posterior superficial group controls the anterior-posterior rotation of the pelvis on the fixed femur. This group consists of the hamstrings and gluteus maximus, erector spinae, rectus abdominis, internal and external obliques, psoas, rectus femoris and sartorius, and the iliofemoral and sacrotuberous ligaments (Figure 10-8). These muscle systems help to actively stabilize the pelvic joints and contribute significantly to load transfer during gait and pelvic rotational activities.5

A, Superior view. B, Inferior view. C, Medial view (female). D, Subdivisions of perineum.

A, Muscles and ligaments involved in posterior tilt. B, Muscles and ligaments involved in anterior tilt.

The symphysis pubis is a fibrocartilaginous joint held together by the pubic ligament. There is a disc of fibrocartilage between the two joint surfaces called the interpubic disc. This joint does allow limited movement.

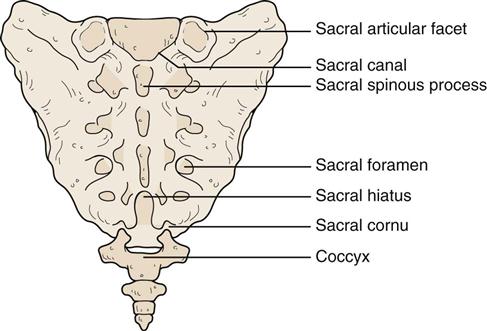

The sacrococcygeal joint is usually a fused line (symphysis) united by a fibrocartilaginous disc. It is found between the apex of the sacrum and the base of the coccyx. Occasionally, the joint is freely movable and synovial. With advanced age, the joint may fuse and be obliterated.

Patient History

In addition to the questions listed under the “Patient History” section in Chapter 1, the examiner should obtain the following information from the patient:

1. Was there any known mechanism of injury? Has there been more than one episode? For example, the sacroiliac joints are commonly injured by a sudden jar caused by inadvertently stepping off a curb, an overzealous kick (either missing the object or hitting the ground), a fall on the buttocks, or a lift and twist maneuver.8 Has the patient experienced any recent falls, twists, or strains? These movements increase the chance of sacroiliac joint sprains.

7. Is there any particular position or activity that aggravates the condition? Climbing or descending stairs, walking, and standing from a sitting position all stress the sacroiliac joint (Tables 10-2 and 10-3).

8. What is the patient’s age? Apophyseal injuries and avulsion fractures of the pelvis can occur in young athletes.9 Ankylosing spondylitis is found primarily in men between the ages of 15 and 35 years. Hypomobility is likely to be seen in men between 40 and 50 and in women after 50 years of age.10

10. Has the patient had any difficulty with micturition? It has been reported that sacroiliac joint dysfunction can lead to urinary problems.11

13. Are there any psychosocial issues that are relevant in the presence of pathology? Questions about anxiety, depression, and other psychosocial issues should be addressed if considered important.12

TABLE 10-2

Pelvic Motions with Lumbar Spine Movement

| Lumbar Spine | Innominate | Sacrum |

| Flexion | Anterior rotation | Nutation followed by counternutation |

| Extension | Posterior rotation (slight) | Nutation |

| Rotation | Same side: posterior rotation Opposite side: anterior rotation |

Nutation on same side |

| Side flexion | Same side: anterior rotation Opposite side: posterior rotation |

Side bend |

Adapted from Dutton M: Orthopedic examination, evaluation and intervention, ed 3, New York, 2012, McGraw-Hill.

TABLE 10-3

Pelvic Motions with Hip Movement

| Hip | Innominate |

| Flexion | Posterior rotation |

| Extension | Anterior rotation |

| Medial rotation | Inflare (medial rotation) |

| Lateral rotation | Outflare (lateral rotation) |

| Abduction | Superior glide |

| Adduction | Inferior glide |

Adapted from Dutton M: Orthopedic examination, evaluation and intervention, ed 3, New York, 2012, McGraw-Hill.

Observation

The patient must be suitably undressed. For the sacroiliac joints to be observed properly, the patient is often required to be nude from the middle of the chest to the toes. If he or she wishes to wear shorts, they must be rolled down as far as possible so that the sacroiliac joints are visible. The posterior, superior, and inferior iliac spines must be visible. The patient stands and is viewed from the front, side, and back. The examiner should note the following:

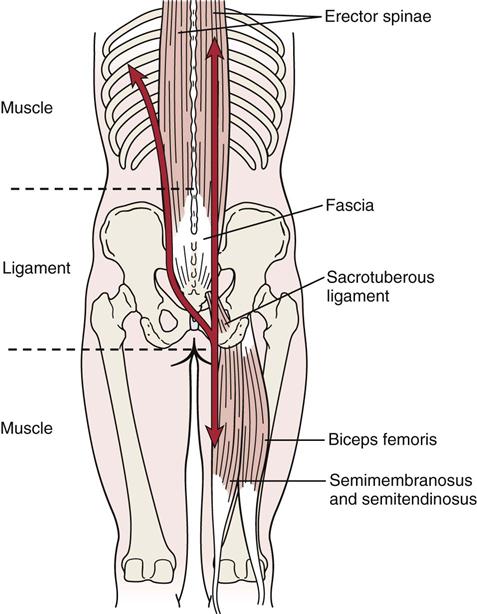

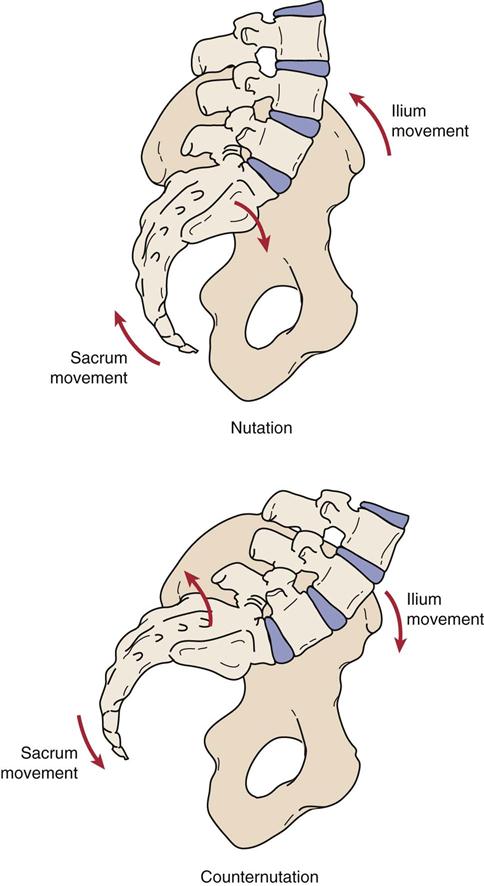

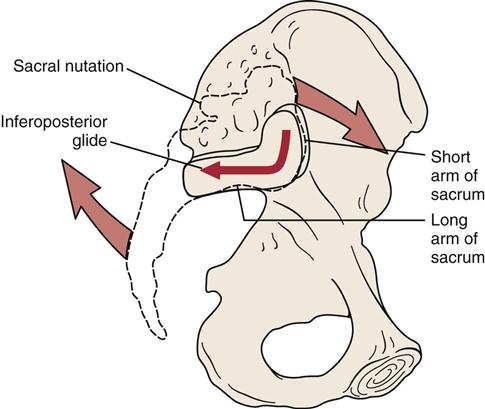

1. Are the posture (see Chapter 15) and gait (see Chapter 14) normal? Nutation5,13 (sacral locking) is the forward motion of the base of the sacrum into the pelvis; it could also be described as the backward rotation of the ilium on the sacrum (Figure 10-9). It is the most stable position of the sacroiliac joint and is an example of form closure. When moving from supine lying to standing, the sacrum normally moves bilaterally, just as it does in early movement of trunk flexion. The ilia move closer together, and the ischial tuberosities move farther apart.10 Unilaterally, the sacrum normally moves with hip flexion of the lower limb.5 Pathologically, if nutation occurs only on one side (where it should occur bilaterally), the examiner will find that the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) is higher and the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) is lower on that side.13 The result is an apparent or functional short leg on the same side.14 Nutation is limited by the anterior sacroiliac ligaments, the sacrospinous ligament, and the sacrotuberous ligament and is more stable than counternutation. Nutation occurs when a person assumes a “pelvic tilt” position. During nutation, the sacrum will slide down its short part and then posteriorly along its long part (Figure 10-10).5

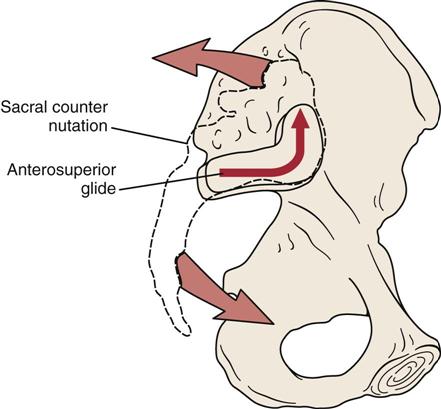

Counternutation (sacral unlocking), or contranutation as it is sometimes called, is the opposite movement to nutation. It indicates an anterior rotation of the ilium on the sacrum or backward motion of the base of the sacrum out of the pelvis.5 The iliac bones move farther apart, and the ischial tuberosities approximate.10 Pathologically, if counternutation occurs only on one side as it does during extension of the extremity on that side, the lower limb on that side will probably be medially rotated.5 Pathological or abnormal counternutation on one side occurs when the ASIS is lower and the PSIS is higher on one side.13 Counternutation is limited by the posterior sacroiliac ligaments. Counternutation occurs when a person assumes a “lordotic” or “anterior pelvic tilt” position. During counternutation, the sacrum will slide anteriorly along its long arm and then superiorly up its short arm (Figure 10-11).5 This motion is resisted by the long posterior sacroiliac ligament supported by the multifidus (contraction of multifidus causes nutation of the sacrum).5

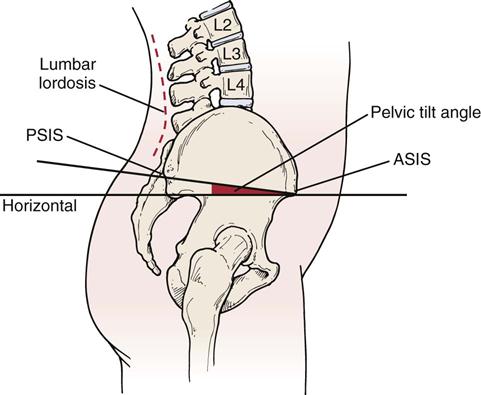

Levine and Whittle15 found that anterior and posterior pelvic tilt has an effect on lumbar lordosis with an average change of 20° being possible (9° posteriorly and 11° anteriorly). Thus, looking for the “neutral pelvis” position becomes important especially for later rehabilitation. Based on their data, a “neutral pelvis” would be somewhere between the two extremes. Pelvic tilt is the angle between a line joining the ASIS and PSIS, and a horizontal line (Figure 10-12). Average pelvic tilt is 11° ± 4°.15,16 Ideal pelvic alignment would see the ASIS on the same vertical plane as the symphysis pubis.17

Three questions should be considered when looking for a “neutral pelvis” and whether the pelvis can be stabilized:

These questions will help the examiner determine if the pelvis (and lumbar spine) can be stabilized during different movements or positions so that other muscles that originate from the pelvis can function properly. The ability to be able to stabilize the pelvis statically or dynamically plays a significant role in proper functioning of the whole kinetic chain. For example, side lying hip abduction should be able to be performed in the frontal plane with the lower limbs, pelvis, trunk and shoulders aligned in the frontal plane (active hip abduction test ![]() ).18 If the leg wobbles, the pelvis tips, the shoulders or trunk rotate, the hip flexes or the abducted limb medially rotates, it is an indication of lack of movement control, lack of muscle balance and an inability to stabilize the pelvis while doing the movement so that the muscles have a firm base from which to function.

).18 If the leg wobbles, the pelvis tips, the shoulders or trunk rotate, the hip flexes or the abducted limb medially rotates, it is an indication of lack of movement control, lack of muscle balance and an inability to stabilize the pelvis while doing the movement so that the muscles have a firm base from which to function.

Gait is often affected if the pathology involves the pelvis. If the sacroiliac joints are not free to move, the stride length is decreased and a vertical limp may be present.8 A painful sacroiliac joint may also cause reflex inhibition of the gluteus medius, leading to a Trendelenburg gait or lurch.

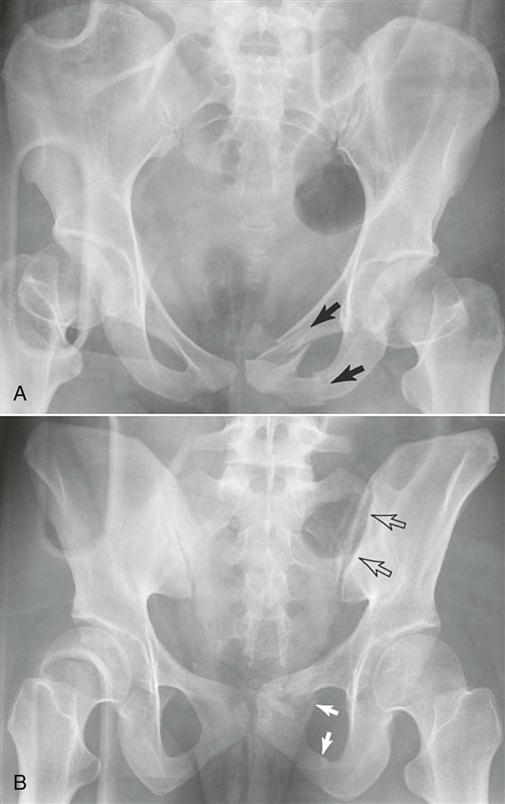

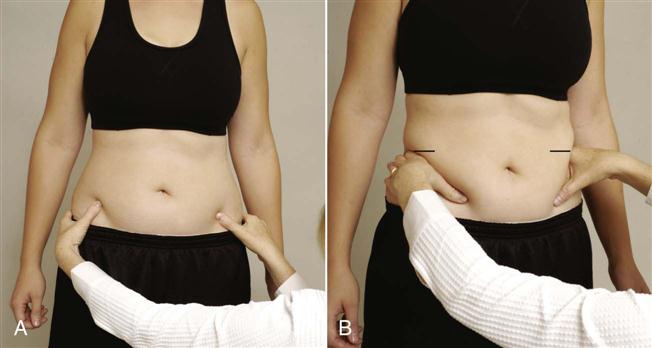

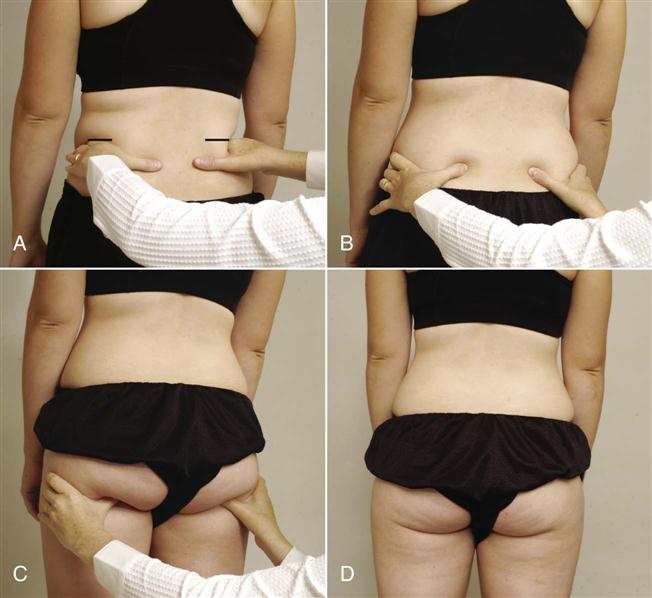

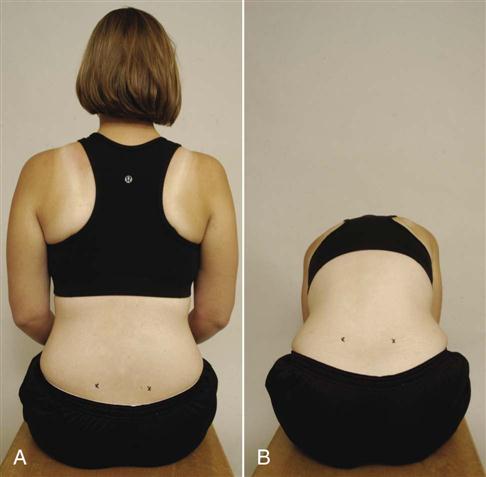

2. Are the ASISs level when viewed anteriorly (Figure 10-13)? On the affected side, the ASIS often tends to be higher and slightly forward. The examiner must remember this difference, if present, when the patient is viewed from behind (Figure 10-14). If the ASIS and PSIS on one side are higher than the ASIS and PSIS on the other side, this indicates an upslip of the ilium on the sacrum on the high side, a short leg on the opposite side, or muscle spasm caused by lumbar pathology (e.g., disc lesion).19–22 If the ASIS is higher on one side and the PSIS is lower at the same time, it indicates an anterior torsion of the sacrum (pathological nutation) on that side.19 This torsion may result in a spinal scoliosis or an altered functional leg length, or both. Anterior rotational dysfunction is seen most frequently following a posterior horizontal thrust of the femur (dashboard injury), golf or baseball swing, or any forced anterior diagonal pattern.20 The sacrum is lower on the side of the pelvis that has rotated backward. The most common rotation of the innominate bones is left posterior torsion or rotation (pathological counternutation). The posterior rotational dysfunctions are usually the result of falling on an ischial tuberosity, lifting when forward flexed with the knees straight, repeated standing on one leg, vertical thrusting onto an extended leg, or sustaining hyperflexion and abduction of hips.

3. Are both pubic bones level at the symphysis pubis? The examiner tests for level equality by placing one finger or thumb on the superior aspect of each pubic bone and comparing the heights (Figure 10-15). If the ASIS on one side is higher, the pubic bone on that side is suspected to be higher, and this can be confirmed by this procedure, indicating a backward torsion problem of the ilium on that side. This procedure is usually done with the patient lying supine.

5. Are the ASISs equidistant from the center line of the body?

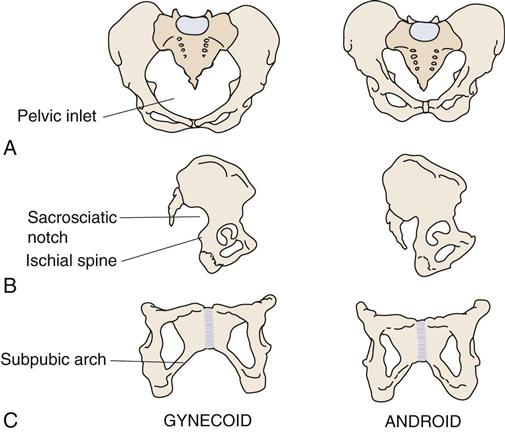

6. What type of pelvis does the patient have?23 Gynecoid and android types are the most common (as described in Figure 10-16 and Table 10-4).

7. Are the iliac crests level? Altered leg length may alter their height.

10. Is there any unilateral or bilateral spasm of the erector spinae muscles?

11. Are the ischial tuberosities level? If one tuberosity is higher, it may indicate an upslip of the ilium on the sacrum on that side.19

13. Are the PSISs equidistant from the center line of the body?

14. Are the sacral sulci equal? If one is deeper, it may indicate a sacral torsion.

A, Level of anterior superior iliac spines (ASISs). B, Level of iliac crests.

A, Level of iliac crests. B, Level of posterior superior iliac spines (PSISs). C, Level of ischial tuberosities. D, Level of gluteal folds.

A, Anterior view. B, Lateral view. C, Anterior view of the pubis and ischium.

TABLE 10-4

A Comparison of the Two Most Common Types of Pelvis

| Feature | Gynecoid | Android |

| Inlet | Round | Triangular |

| Sacrosciatic notch | Average size | Narrow |

| Sacrum | Average | Forward |

| Subpubic arch | Inclination curved | Inclination straight |

Examination

Before assessing the pelvic joints, the examiner should first assess the lumbar spine and hip, unless the history definitely indicates that one of the pelvic joints is at fault. The lumbar spine and hip can, and frequently do, refer pain to the sacroiliac joint area. Because the sacroiliac joints are in part a syndesmosis, movements at these joints are minimal compared with those of the other peripheral joints. It should also be remembered that any condition that alters the position of the sacrum relative to the ilium causes a corresponding change in the position of the symphysis pubis.

Although many tests and test movements have been described to help determine if there is sacroiliac dysfunction, many of them are imprecise and their reliability has been questioned.24–30 At the present time, they are the best tests available. It is important for the examiner to consider all aspects of the assessment, including the history and the patient’s symptoms along with the various tests and movements, before diagnosing sacroiliac joint problems.4,5,24,31–33

Active Movements

Unlike other peripheral joints, the sacroiliac joints do not have muscles that directly control their movement. However, because contraction of the muscles of the other joints may stress these joints or the symphysis pubis, the examiner must be careful during the active or resisted isometric movements of other joints and must be sure to ask the patient about the exact location of the pain on each movement. Table 10-1 outlines the muscles that attach to the pelvis. For example, resisted abduction of the hip can cause pain in the sacroiliac joint on the same side if the joint is injured, because the gluteus medius muscle pulls the ilium away from the sacrum when it contracts strongly. In addition, side flexion to the same side increases the shearing stress to the sacroiliac joint on that side. When doing active movements, the examiner is attempting to reproduce the patient’s symptoms rather than just looking for pain.

The sacroiliac joints move in a “nodding” fashion of anteroposterior rotation. Normally, the PSISs approximate when the patient stands and separate when the patient lies prone. When he or she stands on one leg, the pubic bone on the supported side moves forward in relation to the pubic bone on the opposite side as a result of rotation at the sacroiliac joint.

The stability at the sacroiliac joint is determined by three factors—form closure, force closure, and motor control along with psychological aspects.12,34 Form closure refers to the close packed position of the joint where no outside forces are necessary to hold the joint stable. Thus, intrinsic factors such as joint shape, coefficient of friction of the joint surfaces, and integrity of the ligaments contribute to form closure.5,12,35 Force closure would be similar to the loose packed position in that extrinsic factors, primarily the muscles and their neurological control, along with the capsule are needed to maintain stability of the joint as well as the forces applied to the joint.5,12,35 These two forms of closure and neurological control enable the sacroiliac joints to self lock as they go into close pack and slightly release when the joint unlocks.

During the active movements of the pelvic joints, the examiner looks for unequal movement, loss of or increase in movement (hypomobility or hypermobility), tissue contracture, tenderness, or inflammation.

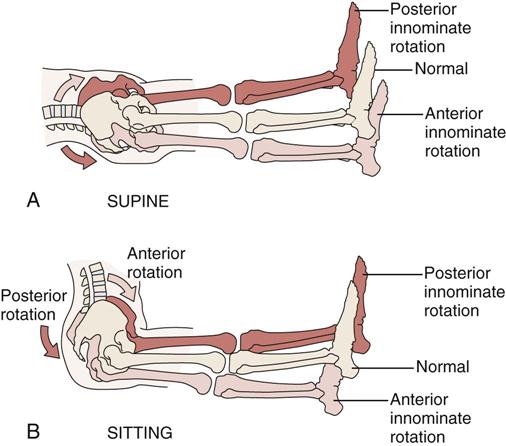

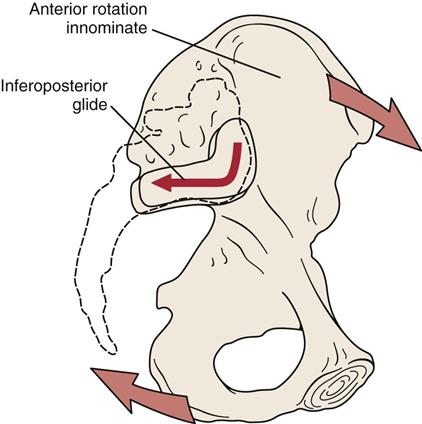

The movements of the spine put a stress on the sacroiliac joints as well as on the lumbar and lumbosacral joints. During forward flexion of the trunk, the innominate bones and pelvic girdle as a whole rotate anteriorly as a unit on the femoral heads bilaterally. The same thing occurs when one rises from supine lying to sitting. If one leg is actively extended at the hip, the innominate on that side will unilaterally rotate anteriorly.5 During the anterior rotation of the innominate bones (counternutation), the innominate slides posteriorly along its long arm and inferiorly down its short arm (Figure 10-17).5 Initially, the sacrum nutates up to about 60° of forward flexion, but once the deep posterior structures (deep and posterior oblique muscle systems, thoracolumbar fascia, and the sacrotuberous ligament) become tight, the innominates continue to rotate anteriorly on the femoral heads, but the sacrum begins to counternutate.5 This counternutation causes the sacroiliac joint to be vulnerable to instability as greater muscle action (force closure) is required to maintain stability with counternutation.7 Thus, the earlier counternutation occurs during forward flexion, the more vulnerable is the sacroiliac joint to instability problems. Excessive counternutation is more likely to occur in patients who have tight hamstrings.5

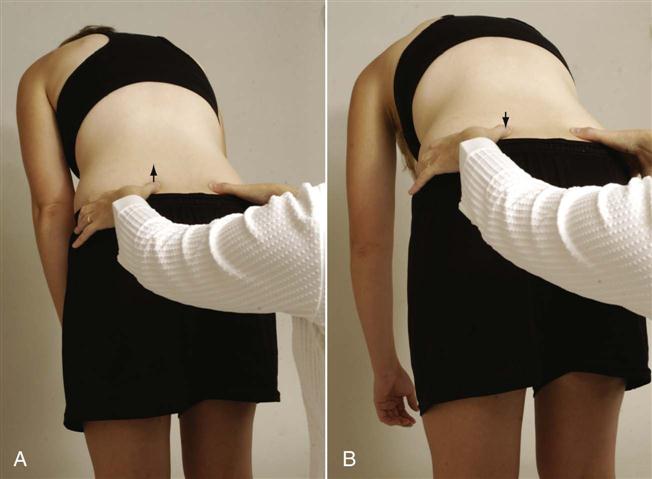

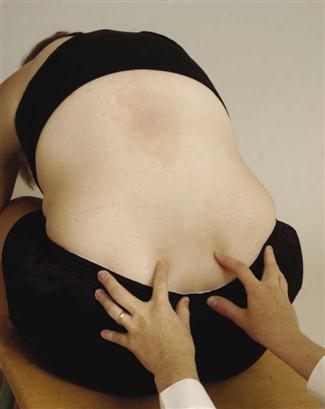

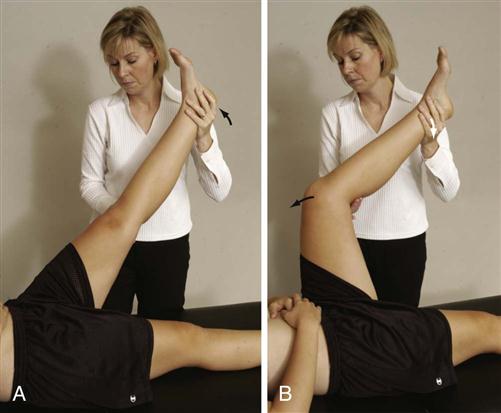

To test forward flexion, the patient stands with weight equally distributed on both legs. The examiner sits behind the patient and palpates both PSISs (Figure 10-18). The patient is asked to bend forward (see Tables 10-2 and 10-3) and the symmetry of movement of the PSIS superiorly is noted. At the same time, the examiner should note the amount of flexion that has occurred when sacral nutation begins. This can be done by having the patient repeat the forward bending motion while the examiner palpates the PSIS (inferior aspect) on one side with one thumb while the other thumb palpates the sacral base so the thumbs are parallel. In the first 45° of forward flexion, the sacrum will move forward (nutate) (Figure 10-19, A), but near 60° (normally), the sacrum will begin to counternutate or move backwards (Figure 10-19, B).5 During the sacral counternutation, the two PSISs should move upward equally in relation to the sacrum and toward each other or approximate. At the same time, the ASIS will tend to flare out.

One thumb is on the posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS); the other thumb is parallel to it on the sacrum. Examiner is feeling for forward movement (nutation) of the sacrum that occurs early in movement (A) and backward movement (counternutation) of the sacrum, which normally occurs around 60° of hip flexion (B).

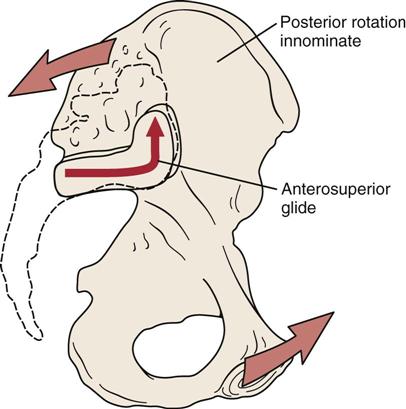

During extension, the opposite movements occur (see Tables 10-2 and 10-3).5,8 During extension or backward bending of the trunk, the innominate bones (the pelvic girdle) as a whole unit rotate posteriorly (nutation) on the femoral heads bilaterally. If one leg is actively flexed at the hip, the innominate on that side unilaterally rotates posteriorly.5 During the posterior rotation of the innominate bones, the innominate slides anteriorly along the long arm and superiorly up the short arm. This movement is the same as sacral nutation (Figure 10-20). With backward bending, both PSISs move inferiorly an equal amount.

To test backward bending, the patient stands with weight equally distributed on both legs. The examiner sits behind the patient and palpates both PSISs. The patient is asked to bend backwards while the examiner notes any asymmetry (Figure 10-21). Normally, the PSISs move inferiorly. During backward bending, the innominate bones and sacrum remain in the same position, so there should be no change in their relationship.5 The examiner palpates both sides of the sacrum at the level of S1. As the patient extends, the sacrum should normally move forward. This is called the sacral flexion test.

Side flexion normally produces a torsion movement between the ilia and the sacrum. As the patient side flexes, the innominate bones bend to the same side and the sacrum rotates slightly in the opposite direction; the thumb of the examiner on the same side (the thumbs are palpating on each side of the sacrum at the level of S1) moves forward. This is called the sacral rotation test.5 If this torsion movement does not occur (e.g., in hypomobility), the patient finds that more effort is required to side flex and it is harder to maintain balance.8

During rotation, the pelvic girdle moves in the direction of the rotation causing intrapelvic torsion. The innominate, which is on the side to which rotation is occurring, rotates posteriorly while the opposite innominate rotates anteriorly, pushing the sacrum into rotation in the same direction (i.e., right rotation of the trunk and pelvis causes right rotation of the sacrum). This causes the sacrum to nutate on the side to which rotation occurs and counternutate on the opposite side.5

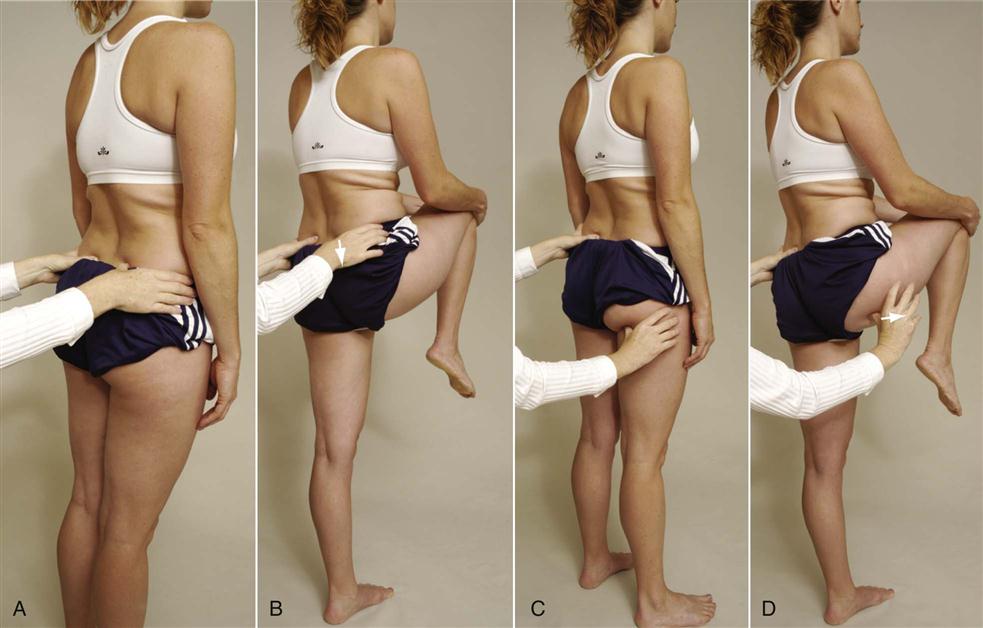

The hip movements performed are also affected by sacroiliac lesions. As the patient flexes each hip maximally, the examiner should observe the ROM present, the pain produced, and the movement of the PSISs. The examiner first notes whether the PSISs are level before the patient flexes the hip. Normally, flexion of the hip with the knee flexed to 90° or more causes the sacroiliac joint on that side to drop or move caudally in relation to the other sacroiliac joint (Gillet test). If this drop does not occur, it may indicate hypomobility on the flexed side. The examiner can observe this movement by placing one thumb over the PSIS and the other thumb over the spinous process of S2 (Figure 10-22, A). In the patient with a normal sacroiliac joint, the thumb on the PSIS drops (Figure 10-22, B). If it is hypomobile, the thumb moves up on hip flexion. The two sides are compared. Sturesson and colleagues36 have questioned whether much movement occurs at all because the stress of doing the test on one leg causes “force closure” of the sacroiliac joints, thus limiting movement.

A, Starting position for sacral spine and posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS). B, Hip flexion; the ilium drops as it normally should (arrow). C, Starting position for sacral spine and ischial tuberosity. D, Hip flexion. Ischial tuberosity moves laterally (arrow), as expected.

The examiner then leaves the one thumb over the sacral spinous process and moves the other thumb over the ischial tuberosity (Figure 10-22, C). The patient is again asked to flex the hip as far as possible. Normally, the thumb over the ischial tuberosity moves laterally (Figure 10-22, D). With a fixed or hypomobile joint, the thumb moves superiorly or toward the head. Again, the two sides are compared.

The examiner then sits in front of the standing patient and palpates the ASIS. Testing one leg at a time, the patient pivots the leg on the heel into medial and lateral rotation. When doing these movements, the ASIS should move medially and laterally. Both sides are compared.5

The position of the sacrum can then be determined. To do this, the examiner tests the patient in two positions—sitting and prone—doing three movements: flexion, staying in neutral, and extension. Before testing, the examiner palpates the base of the sacrum and the inferior lateral angle (near apex) of the sacrum on both sides (Figure 10-23). Normally, the sacral bone and the inferior lateral angle of the sacrum are level (i.e., one is not more anterior or posterior than the other). The first test involves the patient sitting with the feet supported and the spine fully flexed. The examiner palpates the four points (Figure 10-24) and determines their relationship to one another. The patient is then put in prone lying with the spine in neutral and the relationship of the four points determined. The examiner then asks the patient to fully extend the spine and then determines the relationship of the four points. In any of the positions tested, if the examiner found, for example, an anterior left sacral base along with a posterior right inferior lateral angle, it would indicate a left rotated sacrum.5

The final active movements of the pelvis that the examiner may observe is the action of the pelvic floor muscles (Table 10-5). If the pelvis has been found to be unstable or the patient is suffering from incontinence, the examiner can ask the patient to contract the muscles by asking the patient to squeeze the muscles tight by trying to stop peeing and hold the contraction. With strong pelvic floor muscles, the patient should have little trouble holding the contraction for at least 30 seconds.

TABLE 10-5

Muscles of the Pelvic Floor, Their Actions, and Nerve Root Derivation

| Muscles | Action | Nerve Root Derivation |

| Obturator internus | Rotates thigh laterally Abducts flexed thigh at hip |

Nerve to obturator internus |

| Piriformis | Rotates thigh laterally Abducts flexed thigh Stabilizes hip |

Ventral rami of S1, S2 |

| Gluteus maximus | Extends thigh Rotates pelvis back on femur Laterally rotates thigh Abducts thigh |

Inferior gluteal nerve, L5, S1, S2 |

| Levator ani*† | Supports pelvic viscera Raises pelvic floor |

Ventral rami of S3, S4 Perineal nerve |

| Coccygeus† (also called ischiococcygeus) | Supports pelvic viscera Draws coccyx forward |

Ventral rami of S4, S5 |

| Superficial transverse perineal (transverse peroneal profundus) | Supports pelvic viscera | Pudendal nerve, S2, S3, S4 |

*Made up of three muscles: iliococcygeus, pubococcygeus and puborectalis depending on origin and insertion.

†These two muscles make up the pelvic or urogenital diaphragm.

Passive Movements

The passive movements of the pelvic joints involve stressing of the ligaments and the joints themselves. They are not true passive movements, like those done at other joints, but are in reality stress or provocative tests. It should be noted, however, that the effectiveness of these tests in confirming sacroiliac joint problems has been questioned even when combined in a clinical prediction rule.31,37 Lee12 feels these passive movements or tests should be used to determine symmetry or asymmetry of stiffness rather than normal, hypermobile, or hypomobile. It is her contention that asymmetry at the two sacroiliac joints is the problem, not the amount of movement. Laslett, et al.38 and van der Wurff, et al.39 felt that individually the sacroiliac provocative tests were not reliable enough to make a diagnosis, but a combination of the tests were. They felt that if two of four tests were positive (see box on the next page), these tests were the best predictors of an intra-articular sacroiliac joint block. If all six tests were negative, sacroiliac joint pathology could be ruled out.40 Doing the passive movement is more likely to eliminate muscle tension effects that cause compression and increased stiffness.12 Because of their anatomic makeup, the pelvic joints do not move to the same degree or in the same fashion as other joints of the body. When doing these provocative passive movements/tests, the examiner is looking for the reproduction of the patient’s symptoms, not just pain or discomfort.33,41

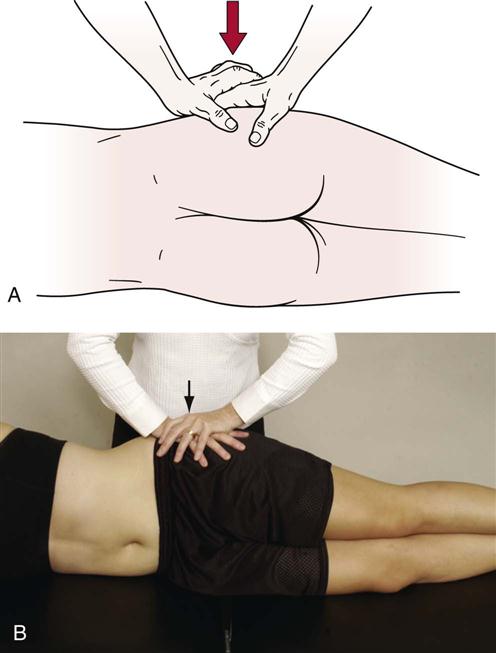

Approximation (Transverse Posterior Stress) Test.5,38

Approximation (Transverse Posterior Stress) Test.5,38

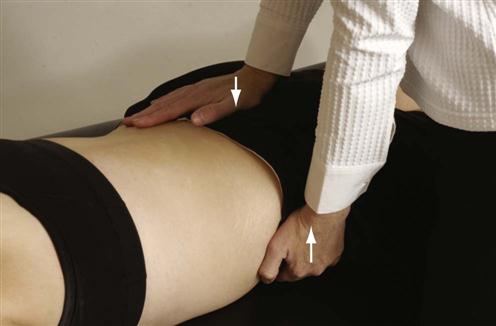

The patient is in the side lying position, and the examiner’s hands are placed over the upper part of the iliac crest, pressing toward the floor (Figure 10-25). The movement causes forward pressure on the sacrum. An increased feeling of pressure in the sacroiliac joints indicates a possible sacroiliac lesion and/or a sprain of the posterior sacroiliac ligaments.

Femoral Shear Test.

Femoral Shear Test.

The patient lies in the supine position. The examiner slightly flexes, abducts, and laterally rotates the patient’s thigh at approximately 45° from the midline. The examiner then applies a graded force through the long axis of the femur, which causes an anterior-to-posterior shear stress to the sacroiliac joint on the same side (Figure 10-26).42

Gapping (Transverse Anterior Stress or Distraction Provocation) Test.5,38

Gapping (Transverse Anterior Stress or Distraction Provocation) Test.5,38

The patient lies supine while the examiner applies crossed-arm pressure to the ASIS (Figure 10-27, A) (some examiners prefer not to cross arms, Figure 10-27, B). The examiner pushes down and out with the arms. The test is positive only if unilateral gluteal or posterior leg pain is produced, indicating a sprain of the anterior sacroiliac ligaments. Care must be taken when performing this test. The examiner’s hands pushing against the ASIS can elicit pain, because the soft tissue is being compressed between the examiner’s hands and the patient’s pelvis.

Ipsilateral Prone Kinetic Test.5,8

Ipsilateral Prone Kinetic Test.5,8

This test is designed to assess the ability of the ilium to flex and to rotate laterally or posteriorly. The patient lies prone while the examiner places one thumb on the PSIS and the other thumb parallel to it on the sacrum. The patient is then asked to actively extend the leg on the same side (Figure 10-28). Normally, the PSIS should move superiorly and laterally. If it does not, it indicates hypomobility with a posterior rotated ilium, or outflare.

Passive Extension and Medial Rotation of Ilium on Sacrum.5,8

Passive Extension and Medial Rotation of Ilium on Sacrum.5,8

The patient is in side lying position on the side that is not being tested. The examiner places one hand over the ASIS area of the anterior ilium. The other hand is placed over the PSIS in such a way that the fingers of the hand palpate the posterior ilium and sacrum. The examiner then pulls the ilium forward with the hand over the ASIS and pushes the posterior ilium forward with the other hand while feeling the relative movement of the ilium on the sacrum (Figure 10-29). The unaffected side is then tested for comparison. If the affected side moves less, it indicates hypomobility and a posterior rotated ilium, or outflare.

Figure 10-29 Passive extension and medial rotation of the ilium on the sacrum.

Figure 10-29 Passive extension and medial rotation of the ilium on the sacrum.The innominate bone is held in extension and medial rotation. The examiner palpates the sacrum and ilium with the fingers while rotating the ilium forward. With hypomobility, the relative movement is less than on the unaffected side, indicating an outflare.

Passive Flexion and Lateral Rotation of Ilium on Sacrum.

Passive Flexion and Lateral Rotation of Ilium on Sacrum.

The patient is positioned as for the previously mentioned test. In this case, the examiner pushes the anterior ilium backward with the anterior hand, and the posterior hand and arm pull the ilium posteriorly while palpating the relative movement (Figure 10-30). The unaffected side is then tested for comparison. If the affected side moves less, it is a sign of hypomobility and an anterior rotated ilium, or inflare.

Figure 10-30 Passive flexion and lateral rotation of the ilium on the sacrum.

Figure 10-30 Passive flexion and lateral rotation of the ilium on the sacrum.The innominate bone is held in flexion and lateral rotation. The examiner palpates the sacrum and ilium with the left fingers while rotating the ilium backward. With hypomobility, the relative movement is less than on the unaffected side, indicating an inflare.

If both this test and the previously mentioned one are positive, it means an upslip has occurred to the ilium relative to the sacrum.

Passive Lateral Rotation of the Hip.

Passive Lateral Rotation of the Hip.

The patient lies supine. The examiner flexes the hip and knee to 90° and then laterally rotates the hip. This movement, provided the hip is normal, stresses the sacroiliac joint on the test side.10

Prone Gapping (Hibb’s) Test.

Prone Gapping (Hibb’s) Test.

The posterior sacroiliac ligaments may be stressed with the patient in the prone position (Figure 10-27, C). To perform the test, the patient’s hips must have full ROM and be pathology free. The patient lies prone, and the examiner stabilizes the pelvis with his or her chest. The patient’s knee is flexed to 90° or greater, and the hip is medially rotated as far as possible. While pushing the hip into the very end of medial rotation, the examiner palpates the sacroiliac joint on the same side. The test is repeated on the other side, with the examiner comparing the degree of opening and the quality of the movement at each sacroiliac joint as well as stressing the posterior sacroiliac ligaments.

Sacral Apex Pressure (Prone Springing or Sacral Thrust) Test.38

Sacral Apex Pressure (Prone Springing or Sacral Thrust) Test.38

The patient lies in a prone position on a firm surface while the examiner places the base of his or her hand at the apex of the patient’s sacrum (Figure 10-31). Pressure is then applied to the apex of the sacrum, causing a shear of the sacrum on the ilium. The test may indicate a sacroiliac joint problem if pain is produced over the joint. The test causes a rotational shift of the sacroiliac joints.

Figure 10-31 Sacral apex pressure test.

Figure 10-31 Sacral apex pressure test.Patient is lying prone.

Sacroiliac Rocking (Knee-to-Shoulder) Test.

Sacroiliac Rocking (Knee-to-Shoulder) Test.

This test is also called the sacrotuberous ligament stress test. The patient is in a supine position (Figure 10-32). The examiner flexes the patient’s knee and hip fully and then adducts the hip. To perform the test properly, both the hip and knee must demonstrate no pathology and have full range of motion (ROM). The sacroiliac joint is “rocked” by flexion and adduction of the patient’s hip. To do the test properly, the knee is moved toward the patient’s opposite shoulder. Some authors5,42 believe that the hip should be medially rotated as it is flexed and adducted to increase the stress on the sacroiliac joint. Simultaneously, the sacrotuberous ligament may be palpated (see Figure 10-2 for location) for tenderness. Pain in the sacroiliac joints indicates a positive test. Care must be taken, because the test places a great deal of stress on the hip and sacroiliac joints. If a longitudinal force is applied through the hip in a slow, steady manner (for 15 to 20 seconds) in an oblique and lateral direction, further stress is applied to the sacrotuberous ligament.5 While performing the test, the examiner may palpate the sacroiliac joint on the test side to feel for the slight amount of movement that normally is present.

Figure 10-32 Sacroiliac rocking (knee-to-shoulder) test.

Figure 10-32 Sacroiliac rocking (knee-to-shoulder) test. “Squish” Test.

“Squish” Test.

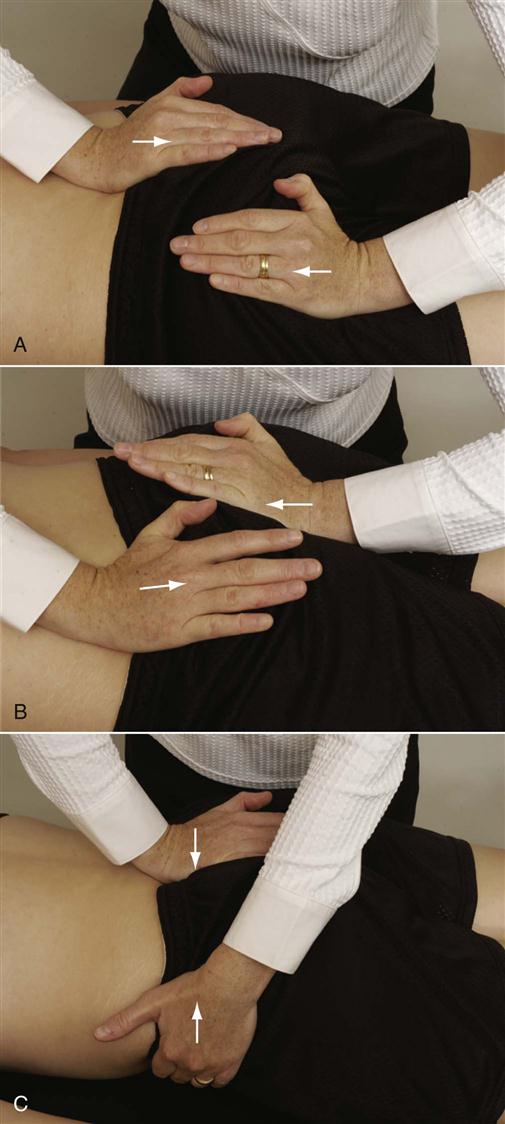

With the patient in the supine position, the examiner places both hands on the patient’s ASISs and iliac crests and pushes down and in at a 45° angle (Figure 10-33). This movement tests the posterior sacroiliac ligaments. A positive test is indicated by pain.

Superoinferior Symphysis Pubis Stress Test.5,8

Superoinferior Symphysis Pubis Stress Test.5,8

The patient lies supine. The examiner places the heel of one hand over the superior pubic ramus of one pubic bone and the heel of the other hand over the inferior pubic ramus of the other pubic bone. The examiner then squeezes the hands together, applying a shearing force to the symphysis pubis (Figure 10-34). Production of pain in the symphysis pubis is considered a positive test.

Thigh Thrust Test (Also Called Oostagard, 4P, Sacrotuberous Stress, or POSH [Posterior Shear] Test).38

Thigh Thrust Test (Also Called Oostagard, 4P, Sacrotuberous Stress, or POSH [Posterior Shear] Test).38

The patient lies supine while the examiner passively flexes the hip on the test side to 90°. Using one hand to palpate the sacroiliac joint, the examiner thrusts down through the knee and hip on the text side (Figure 10-35). Pain in the sacroiliac joint on thrusting is a positive test.

Figure 10-35 Thigh thrust test.

Figure 10-35 Thigh thrust test. Torsion Stress Test.5

Torsion Stress Test.5

The patient lies prone. The examiner palpates the spinous process of L5 with one thumb holding it stable. The examiner’s other hand is placed around the anterior ilium on the opposite side and lifts the contralateral ilium up (Figure 10-36). This rotational movement stresses the lumbosacral junction, the iliolumbar ligament, the anterior sacroiliac ligament, and the sacroiliac joint.

Patient is lying prone.

Resisted Isometric Movements

As previously stated, there are no specific muscles acting directly on the sacroiliac joints and symphysis pubis. However, contraction of adjacent muscles can stress these joints and cause force closure.35 The examiner performs these movements with the patient supine and attempts to reproduce the patient’s symptoms.

Functional Assessment

Functional assessment of the pelvic joints by themselves is very difficult because these joints do not work in isolation. Functionally, they should be considered part of the lumbar spine or part of the hip joint, depending on the area that the presenting pathology most affects.

Special Tests

The examiner should use only those special tests that are considered necessary to confirm the diagnosis. Few special tests that accurately diagnose sacroiliac joint pathology have been validated.35 Dreyfuss, et al.31,43 showed that the sacral sulcus (the area of soft tissue just medial to the PSIS) was tender in 89% of sacroiliac joint patients. When performing these tests, especially the stress or provocative tests, the examiner is attempting to reproduce the patient’s symptoms.

For the reader who would like to review them, the reliability, validity, specificity, sensitivity, and odds ratios of some of the special tests used in the pelvis are available on the Evolve website.

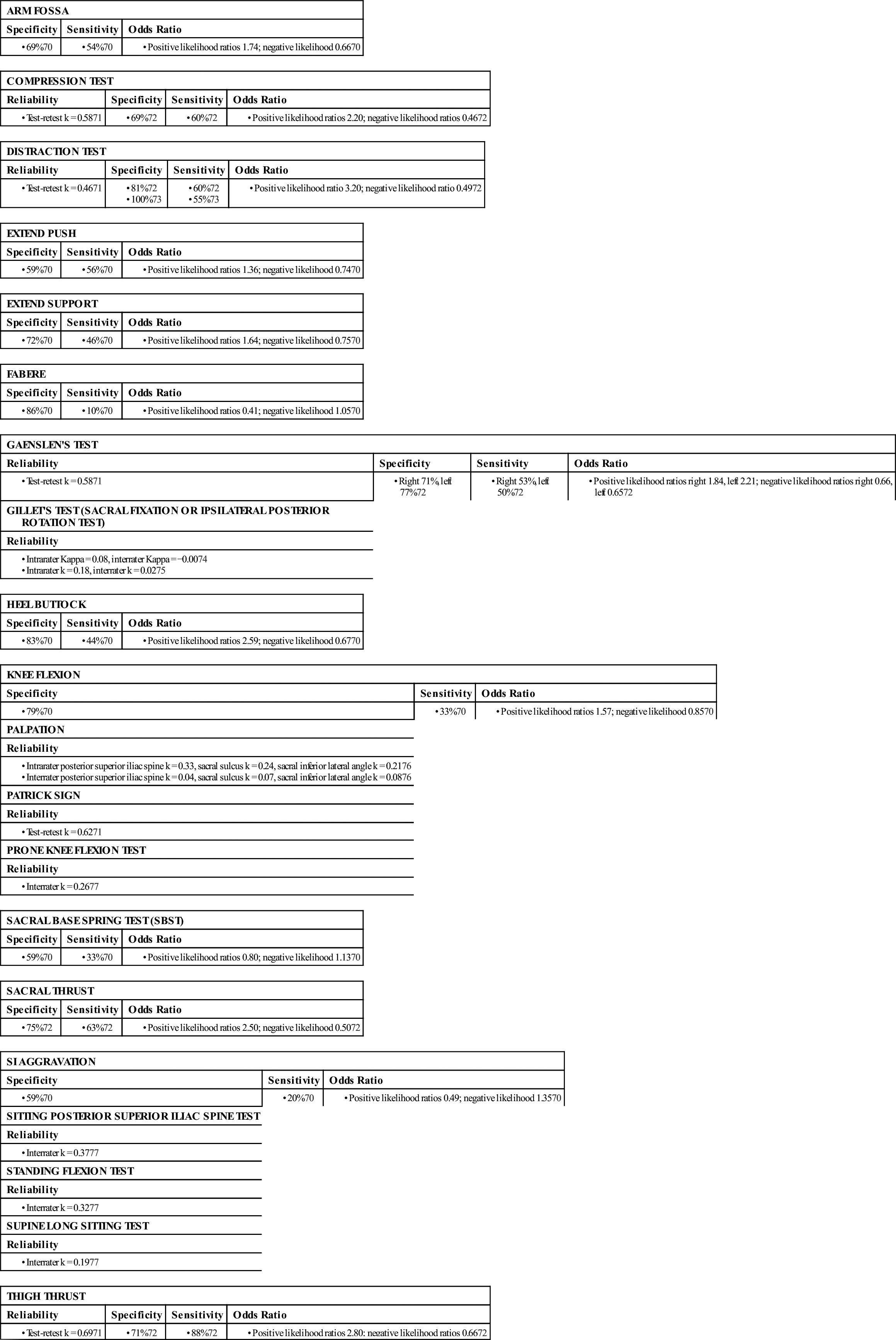

APPENDIX 10-1

Reliability, Validity, Specificity, and Sensitivity of Special/Diagnostic Tests Used in the Pelvis

| ARM FOSSA | ||

| Specificity | Sensitivity | Odds Ratio |

| COMPRESSION TEST | |||

| Reliability | Specificity | Sensitivity | Odds Ratio |

| DISTRACTION TEST | |||

| Reliability | Specificity | Sensitivity | Odds Ratio |

| EXTEND PUSH | ||

| Specificity | Sensitivity | Odds Ratio |

| EXTEND SUPPORT | ||

| Specificity | Sensitivity | Odds Ratio |

| FABERE | ||

| Specificity | Sensitivity | Odds Ratio |

| GAENSLEN’S TEST | |||

| Reliability | Specificity | Sensitivity | Odds Ratio |

| GILLET’S TEST (SACRAL FIXATION OR IPSILATERAL POSTERIOR ROTATION TEST) |

| Reliability |

| HEEL BUTTOCK | ||

| Specificity | Sensitivity | Odds Ratio |

| KNEE FLEXION | ||

| Specificity | Sensitivity | Odds Ratio |

| PALPATION |

| Reliability |

| PATRICK SIGN |

| Reliability |

| PRONE KNEE FLEXION TEST |

| Reliability |

| SACRAL BASE SPRING TEST (SBST) | ||

| Specificity | Sensitivity | Odds Ratio |

| SACRAL THRUST | ||

| Specificity | Sensitivity | Odds Ratio |

| SI AGGRAVATION | ||

| Specificity | Sensitivity | Odds Ratio |

| SITTING POSTERIOR SUPERIOR ILIAC SPINE TEST |

| Reliability |

| STANDING FLEXION TEST |

| Reliability |

| SUPINE LONG SITTING TEST |

| Reliability |

| THIGH THRUST | |||

| Reliability | Specificity | Sensitivity | Odds Ratio |

If muscle tightness is suspected as part of the problem, muscle should be tested for length.

Tests for Neurological Involvement

Prone Knee Bending (Nachlas) Test.

Prone Knee Bending (Nachlas) Test.

Normally, this is used to test for a tight rectus femoris, an upper lumbar joint lesion, an upper spine nerve root lesion, or a hypomobile sacroiliac joint. The patient lies prone, and the examiner flexes the knee so that the heel is brought to the buttocks. If pain is felt in the front of the thigh before full range is reached, the problem is in the rectus femoris muscle. If the pain is in the lumbar spine, the problem is in the lumbar spine, usually the L3 nerve root, especially if these are radicular symptoms. If the problem is a hypomobile sacroiliac joint, the ipsilateral pelvic rim (ASIS) rotates forward, usually before the knee reaches 90° flexion.42,46

Straight Leg Raising (Lasègue’s) Test.

Straight Leg Raising (Lasègue’s) Test.

Although the Lasègue sign is primarily considered a test of the neurological tissue around the lumbar spine, this test also places a stress on the sacroiliac joints. With the patient in the supine position (Figure 10-37), the examiner passively flexes the patient’s hip with the knee extended. Pain occurring after 70° is usually indicative of joint pain. However, in hypermobile persons, joint pain is often not experienced until after 120° of hip flexion. Therefore, it is more important to watch for the production of the patient’s symptoms than for the actual ROM. In addition, the ROM obtained should be compared with the unaffected side. If the examiner then does a passive bilateral straight leg raising (SLR) test in a similar fashion, pain occurring before 70° is usually indicative of sacroiliac joint problems. DonTigny47 has reported that the straight leg raise can be affected by sacroiliac problems. If, when doing SLR, the pain in the sacroiliac joint is unaltered or decreases, the examiner may suspect an anterior torsion. If the pain increases in the sacroiliac joint, a posterior torsion is possible. If pain increases on the opposite side, an anterior torsion on the opposite side should be suspected.

A, Unilateral (head may be flexed, ankle may be dorsiflexed, or both). B, Bilateral.

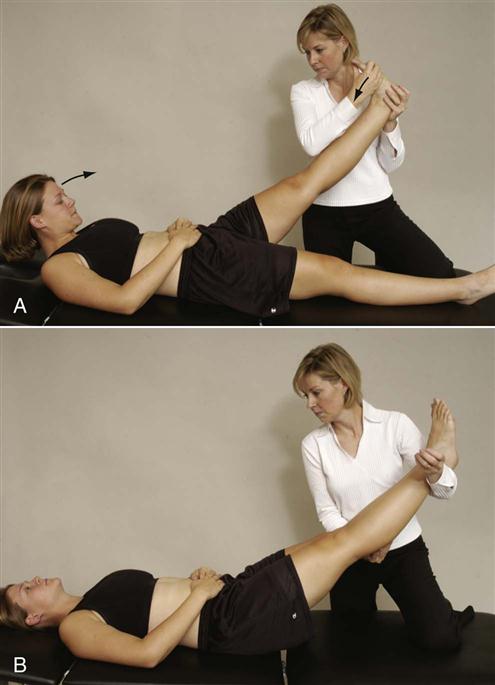

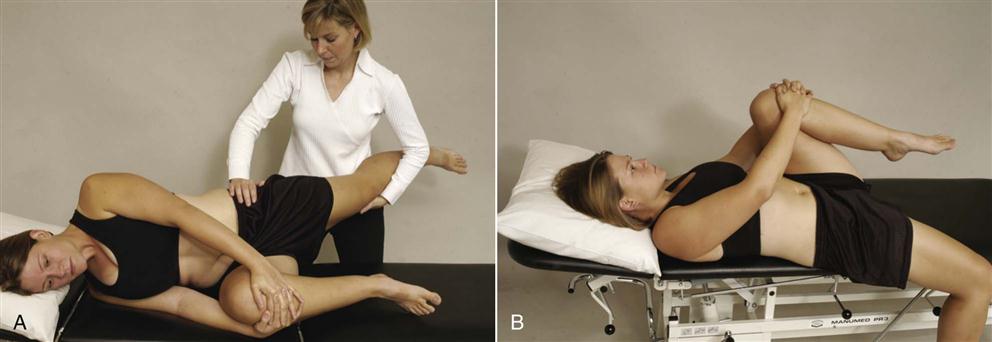

Lee5 advocated several modifications to the straight leg test (Figure 10-38, A) if sacroiliac joint problems are suspected. These tests are called active SLR tests and were originally designed to test for postpartum pelvic problems.48–50 In the first modification, Lee recommends that the test be done actively by the patient in supine (supine active straight leg raise test ![]() ).12,48–50 As the patient actively lifts the leg, the examiner asks whether the patient notes any “effort differences” between the two sides. The examiner then stabilizes and compresses the pelvis while the patient actively does the straight leg raise providing form closure of the joints by squeezing the innominate bones together anteriorly (Figure 10-38, B). If the pain decreases or the SLR is easier to do with form closure (with no increased neurological signs), the test is considered positive for possible sacroiliac joint problems. At the same time, the examiner can check the contraction of the pelvic floor/transverse abdominus/multifidus force couple by palpating medial to the ASIS bilaterally. If the force couple functions properly, tension is felt symmetrically and the abdomen moves inward. If superficial tension is felt, it means the internal obliques are contracting, and there is a force-couple imbalance.12 Multifidus may be palpated close to the spinous process, and it should contract when the pelvic floor contracts. Another modification tests force closure at the sacroiliac joints.5 The patient is asked to flex and rotate the trunk toward the side that the SLR is actively being performed. The trunk motion is resisted by the examiner (Figure 10-38, C). The two sides are compared for any difference. Force closure tests the ability of the muscles to stabilize the sacroiliac joints during movement.

).12,48–50 As the patient actively lifts the leg, the examiner asks whether the patient notes any “effort differences” between the two sides. The examiner then stabilizes and compresses the pelvis while the patient actively does the straight leg raise providing form closure of the joints by squeezing the innominate bones together anteriorly (Figure 10-38, B). If the pain decreases or the SLR is easier to do with form closure (with no increased neurological signs), the test is considered positive for possible sacroiliac joint problems. At the same time, the examiner can check the contraction of the pelvic floor/transverse abdominus/multifidus force couple by palpating medial to the ASIS bilaterally. If the force couple functions properly, tension is felt symmetrically and the abdomen moves inward. If superficial tension is felt, it means the internal obliques are contracting, and there is a force-couple imbalance.12 Multifidus may be palpated close to the spinous process, and it should contract when the pelvic floor contracts. Another modification tests force closure at the sacroiliac joints.5 The patient is asked to flex and rotate the trunk toward the side that the SLR is actively being performed. The trunk motion is resisted by the examiner (Figure 10-38, C). The two sides are compared for any difference. Force closure tests the ability of the muscles to stabilize the sacroiliac joints during movement.

Figure 10-38 Functional test of supine-active straight leg raise.

Figure 10-38 Functional test of supine-active straight leg raise.A, Patient actively does straight leg raise to provide comparison with ease of doing test in other two positions. B, With form closure augmented (compression of innominate bones). C, With force closure augmented (resisted muscle action).

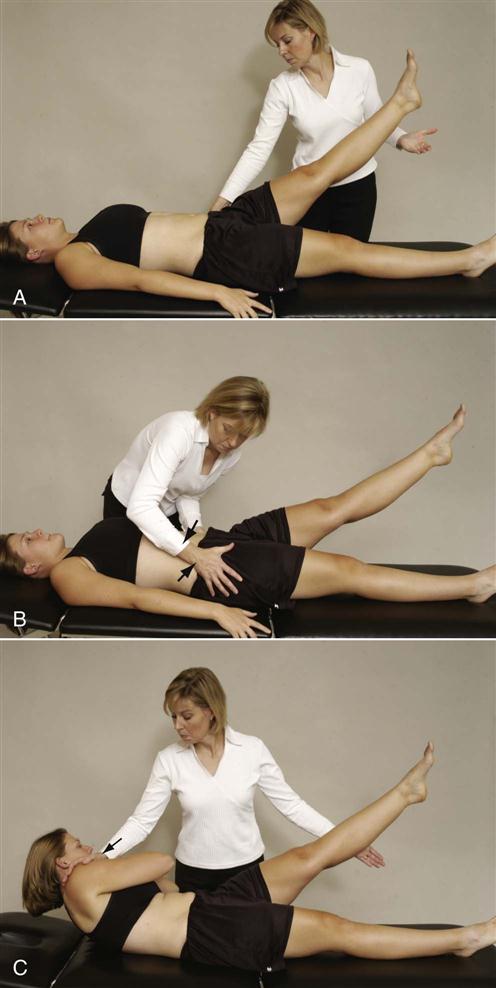

Lee5 also advocates doing active hip extension (active prone hip extension test) with the leg straight under three conditions (prone active straight leg raise test ![]() ). The first condition is hip extension (Figure 10-39, A). The second condition includes the same movement as the first with the examiner applying manual compression to the innominate bones (form closure) (Figure 10-39, B). The third condition has the examiner resisting extension of the contralateral medially rotated arm (force closure) as the patient extends the straight leg (Figure 10-39, C). If function improves when force closure stabilization is used, exercise will probably benefit the patient.

). The first condition is hip extension (Figure 10-39, A). The second condition includes the same movement as the first with the examiner applying manual compression to the innominate bones (form closure) (Figure 10-39, B). The third condition has the examiner resisting extension of the contralateral medially rotated arm (force closure) as the patient extends the straight leg (Figure 10-39, C). If function improves when force closure stabilization is used, exercise will probably benefit the patient.

Figure 10-39 Functional test of prone-active straight leg raise.

Figure 10-39 Functional test of prone-active straight leg raise.A, Patient actively extends straight leg to provide comparison with ease of doing test in other two positions. B, With form closure augmented (compression of innominate bones). C, With force closure augmented (resisted muscle action).

A more detailed description of the SLR test is given in Chapter 9.

Tests for Sacroiliac Joint Involvement

Lee12 has reported that active mobility tests should not be used to test the passive mobility of the sacroiliac joints. She felt passive movements used to look for asymmetry were more effective.

Flamingo Test or Maneuver.

Flamingo Test or Maneuver.

The patient is asked to stand on one leg (Figure 10-40). When the patient is standing on one leg, the weight of the trunk causes the sacrum to shift forward and distally (caudally) with forward rotation. The ilium moves in the opposite direction. On the non–weight-bearing side, the opposite occurs, but the stress is greatest on the stance side.10 Pain in the symphysis pubis or sacroiliac joint indicates a positive test for lesions in whichever structure is painful. The stress may be increased by having the patient hop on one leg. This position is also used to take a stress x-ray of the symphysis pubis.

Figure 10-40 Flamingo test.

Figure 10-40 Flamingo test. Gaenslen’s Test.

Gaenslen’s Test.

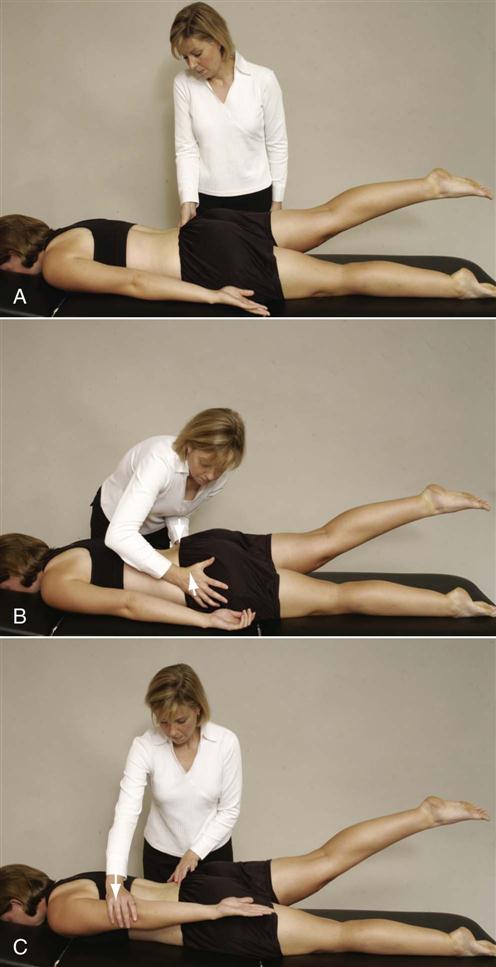

The patient lies on the side with the upper leg (test leg) hyperextended at the hip (Figure 10-41, A). The patient holds the lower leg flexed against the chest. The examiner stabilizes the pelvis while extending the hip of the uppermost leg. Pain indicates a positive test. The pain may be caused by an ipsilateral sacroiliac joint lesion, hip pathology, or an L4 nerve root lesion.

A, With patient in side lying position, examiner extends test leg. B, With patient supine, test leg is extended over edge of table.

Gaenslen’s test is sometimes done with the patient supine (Figure 10-41, B), but this position may limit the amount of hyperextension available. The patient is positioned so that the test hip extends beyond the edge of the table. The patient draws both legs up onto the chest and then slowly lowers the test leg into extension. The other leg is tested in a similar fashion for comparison. Pain in the sacroiliac joints is indicative of a positive test.

Gillet’s (Sacral Fixation) Test.20

Gillet’s (Sacral Fixation) Test.20

This test is also called the ipsilateral posterior rotation test. While the patient stands, the sitting examiner palpates the PSISs with one thumb and the other thumb parallel with the first thumb on the sacrum. The patient is then asked to stand on one leg while pulling the opposite knee up toward the chest. This causes the innominate bone on the same side to rotate posteriorly. The test is repeated with the other leg palpating the other PSIS. If the sacroiliac joint on the side on which the knee is flexed (i.e., the ipsilateral side) moves minimally or up, the joint is said to be hypomobile, or “blocked,” indicating a positive test.30 On the normal side, the test PSIS moves down or inferiorly (Figure 10-42). This test is similar to the test performed during hip flexion in active movement; the only difference is the points of palpation during the movement.

Figure 10-42 Gillet’s (sacral fixation) test.

Figure 10-42 Gillet’s (sacral fixation) test.Jackson4 has suggested a modification to the test. After completing the Gillet’s test, he suggests that the examiner palpate the same PSIS and sacrum and ask the patient to do a repeat of the Gillet test using the other leg, which causes the opposite innominate bone to rotate posteriorly. As the patient flexes the hip and knee, the lumbar spine begins to flex, causing the sacrum to move inferiorly and resulting in the test innominate (side opposite to the leg being flexed) to rotate anteriorly.

Goldthwait’s Test.

Goldthwait’s Test.

The patient lies supine. The examiner places one hand under the lumbar spine so that each finger is in an interspinous space (i.e., L5–S1, L4–L5, L3–L4, and L2–L3 interspaces). The examiner uses the other hand to perform SLR. If pain is elicited before movement occurs at the interspaces, the problem is in the sacroiliac joint. Pain during interspace movement indicates a lumbar spine dysfunction. As with the SLR test, pain may be referred along the course of the sciatic nerve if there is neurological (e.g., nerve root) involvement.46

Ipsilateral Anterior Rotation Test.5

Ipsilateral Anterior Rotation Test.5

The patient stands with weight equally distributed on both feet. The examiner sits behind the patient and palpates one PSIS with one thumb and the sacrum on a parallel line with the other thumb. The patient is asked to extend the ipsilateral leg. Normally, the PSIS should move superiorly and laterally (Figure 10-43). The other side is tested for comparison. This test determines the ability of the innominate on the test side to rotate anteriorly while the sacrum rotates to the opposite side.5

Laguere’s Sign.

Laguere’s Sign.

The patient lies supine (Figure 10-44). To test the left sacroiliac joint, the examiner flexes, abducts, and laterally rotates the patient’s left hip, applying an overpressure at the end of the ROM. The examiner must stabilize the pelvis on the opposite side by holding the opposite ASIS down. Pain in the left sacroiliac joint constitutes a positive test. The other side is tested for comparison. This test should be performed with caution for patients with hip pathology, because hip pain may ensue.

Mazion’s Pelvic Maneuver (Standing Lunge Test).51

Mazion’s Pelvic Maneuver (Standing Lunge Test).51

The patient stands in a straddle position with the limb on the unaffected side forward so that the feet are 0.5 to 1 meter (2 to 3 feet) apart. The patient bends forward, trying to touch the floor, until the heel of the back leg lifts off the floor. If pain is produced in the lower trunk on the affected side, it is considered a positive test for unilateral forward displacement of the ilium relative to the sacrum.

Patrick Test.

Patrick Test.

See Chapter 11.

Piedallu’s Sign.

Piedallu’s Sign.

The patient is asked to sit on a hard, flat surface (Figure 10-45). This position keeps the muscles (e.g., hamstrings) from affecting the pelvic flexion symmetry and increases the stability of the ilia. In effect, it is a test of the sacrum on the ilia. The examiner palpates the PSISs and compares their heights. If one PSIS, usually the painful one, is lower than the other, the patient is asked to forward flex while remaining seated. If the lower PSIS becomes the higher one on forward flexion, the test is positive; it is that side that is affected. Because the affected joint does not move properly and is hypomobile, it goes from a low to a high position. This is believed to indicate an abnormality in the torsion movement at the sacroiliac joint.

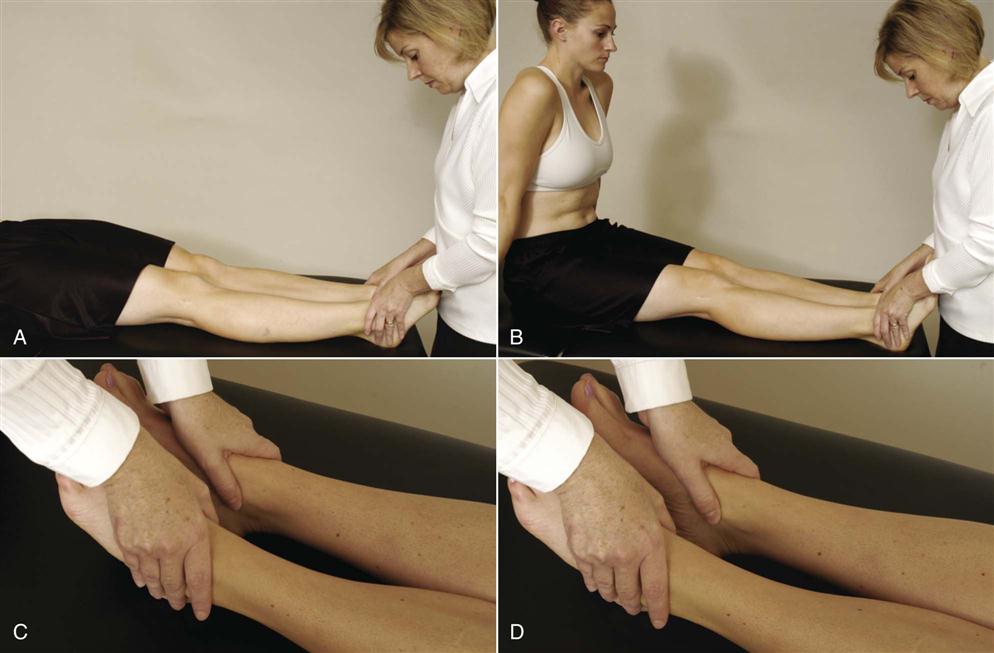

Supine-to-Sit (Long Sitting) Test.

Supine-to-Sit (Long Sitting) Test.

The patient lies supine with the legs straight. The examiner ensures that the medial malleoli are level. The patient is asked to sit up, and the examiner observes whether one leg moves up (proximally) farther than the other (Figures 10-46 and 10-47). If so, it is believed that there is a functional leg length difference resulting from a pelvic dysfunction caused by pelvic torsion or rotation.42,52,53 It may also be caused by spasm of the lumbar muscles in the presence of lumbar pathology.

A, Initial position. B, Final position. C, Symmetric leg lengths. D, Asymmetric leg lengths.

Leg length reversal; supine (A) versus sitting (B). If the lower limb on the affected side appears longer when a patient lies supine but shorter when sitting, the test is positive, implicating anterior innominate rotation of the affected side. (Redrawn from Wadsworth CT, editor: Manual examination and treatment of the spine and extremities, Baltimore, 1988, Williams & Wilkins, p. 82.)

Yeoman’s Test.

Yeoman’s Test.

The patient lies prone. The examiner flexes the patient’s knee to 90° and extends the hip (Figure 10-48). Pain localized to the sacroiliac joint indicates pathology in the anterior sacroiliac ligaments. Lumbar pain indicates lumbar involvement.46 Anterior thigh paresthesia may indicate a femoral nerve stretch.

Tests for Limb Length

Functional Limb Length Test.54

Functional Limb Length Test.54

The patient stands relaxed while the examiner palpates the ASISs and PSISs, noting any asymmetry. The patient is then placed in the “correct” stance (subtalar joints neutral, knees fully extended, and toes facing straight ahead), and the ASISs and PSISs are palpated with the examiner noting whether the asymmetry has been corrected. If the asymmetry has been corrected by “correct” positioning of the limb, the leg is structurally normal (i.e., the bones have proper length), but abnormal joint mechanics (functional deficit) are producing a functional leg length difference. Therefore, if the asymmetry is corrected by proper positioning, the test is positive for a functional leg length difference.

Leg Length Test.

Leg Length Test.

The leg length test, described in detail in Chapter 11, should always be performed if the examiner suspects a sacroiliac joint lesion. Nutation (backward rotation) of the ilium on the sacrum results in a decrease in leg length—as does counternutation (anterior rotation) on the opposite side. If the iliac bone on one side is lower, the leg on that side is usually longer.47 True leg length is measured by placing the patient in a supine position with the ASISs level and the patient’s lower limbs perpendicular to the line joining the ASISs (Figure 10-49). Using a flexible tape measure, the examiner obtains the distance from the ASIS to the medial or lateral malleolus on the same side. The measurement is repeated on the other side, and the results are compared. A difference of 1 to 1.3 cm (0.5 to 1 inch) is considered normal. It should be remembered, however, that leg length differences within this range may also be pathological if symptoms result.55

Other Tests

Functional Hamstring Length.5

Functional Hamstring Length.5

The patient sits on the examining table with the knees flexed to 90°, no weight on feet, and spine in neutral. The examiner sits behind the patient and palpates the PSIS with one thumb while the other thumb rests parallel on the sacrum. The patient is asked to actively extend the knee (Figure 10-50). Normally, full knee extension is possible without posterior rotation of the pelvis or flexion of the lumbar spine. Tight hamstrings would cause the pelvis to rotate posteriorly and/or the spine to flex.

90–90 SLR Test for Hamstring Tightness.

90–90 SLR Test for Hamstring Tightness.

See Chapters 11 and 12.

Sign of the Buttock Test.

Sign of the Buttock Test.

With the patient supine, the examiner performs a passive unilateral SLR test as done previously (Figure 10-51). If restriction or pain is found on one side, the examiner flexes the patient’s knee while holding the patient’s thigh in the same position. Once the knee is flexed, the examiner tries to flex the hip further. If the problem is in the lumbar spine or hamstrings, hip flexion increases. This finding indicates a negative sign of the buttock test. If hip flexion does not increase when the knee is flexed, it is a positive sign of the buttock test and indicates pathology in the buttock, such as a bursitis, tumor, or abscess. The patient with this pathology would also exhibit a noncapsular pattern of the hip.

Thoracolumbar Fascia Length.5

Thoracolumbar Fascia Length.5

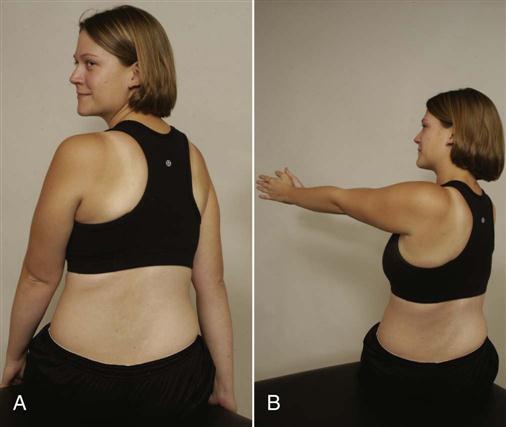

The patient sits on the examining table with the knees bent to 90° and a neutral spine. The examiner stands behind the patient. The patient is asked to rotate left and right fully and the examiner notes the ROM available (Figure 10-52, A). The patient is then asked to forward flex the arms to 90° and laterally rotate and adduct the arms so the little fingers touch each other and palms face up (Figure 10-52, B). Holding this arm position, the patient is again asked to rotate left and right as far as possible. The motion will be restricted in the second set of rotations if the thoracolumbar fascia or latissimus dorsi are tight.

Trendelenburg Test or Sign.

Trendelenburg Test or Sign.

The patient is asked to stand or balance first on one leg and then on the other (Figure 10-53). While the patient is balancing on one leg, the examiner watches the movement of the pelvis. If the pelvis on the side of the non-stance leg rises, the test is considered negative, because the gluteus medius muscle on the opposite (stance) side lifts it up as it normally does in one-legged stance. If the pelvis on the side of the non-stance leg falls, the test is considered positive and is an indication of weakness or instability of the hip abductor muscles, primarily the gluteus medius on the stance side. Therefore, although the examiner is watching what happens on the non-stance side, it is the stance side that is being tested.

Reflexes and Cutaneous Distribution

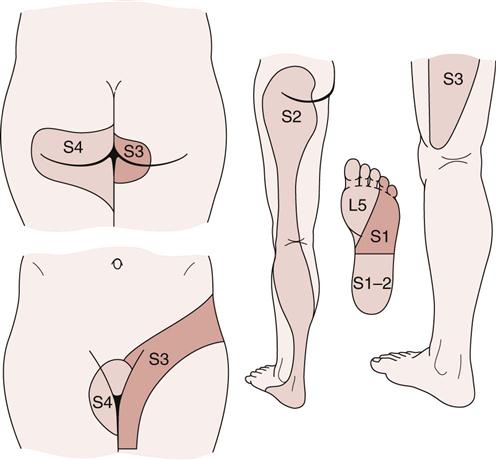

There are no reflexes to test for the pelvic joints. However, the examiner must be aware of the dermatomes from the sacral nerve roots (Figure 10-54). Pain may be referred to the sacroiliac joints from the lumbar spine and the hip (Figure 10-55). In addition, the sacroiliac joint may refer pain to these same structures or along the courses of the superior gluteal and obturator nerves. The muscles of the spine may also refer pain to the sacral area (Table 10-6).

TABLE 10-6

Muscles and Referral of Pain to Pelvic Area

| Muscle | Referral Pattern |

| Longissimus thoracis | From lower thoracic spine to posterior iliac crest and gluteal area |

| Iliocostalis lumborum | From area lateral to lumbar spine to sacral and gluteal area |

| Multifidus | Sacral area |

Peripheral Nerve Injuries about the Pelvis

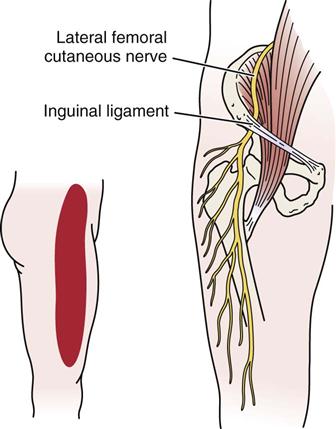

Meralgia Paresthetica.56

This condition is the result of pressure or entrapment of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve near the ASIS, because the nerve passes under the inguinal ligament. It may result from trauma such as that caused by a seat belt in a car accident, during delivery (in stirrups), by tight clothing, or as a complication of surgery (e.g., hernia). This nerve is sensory only, so the patient experiences sensory alteration and/or burning pain on the lateral aspect of the thigh (Figure 10-56).

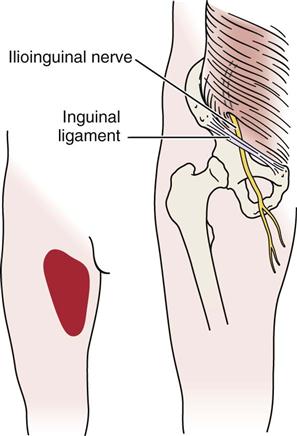

Ilioinguinal Nerve.57

This nerve, which lies within the transverse abdominus muscle, may be compressed by spasm of the muscle (Figure 10-57). The nerve is sensory only, and the sensory alteration and/or pain occurs in the superior aspect of the anterior thigh (in the L1 dermatome area), as well as in the scrotum or labia. There have been reports in the literature58–61 that this nerve may be entrapped with injury to the external oblique muscle aponeurosis (hockey player’s syndrome). The patient feels pain especially on ipsilateral hip extension and contralateral torso rotation. The pain may radiate to the groin, scrotum, hip, and back.

Joint Play Movements

The joint play movements (Figure 10-58) are minimal for the sacroiliac joints and are similar to the passive movements in that they are stress or provocative tests.

A, Cephalad movement of sacrum with caudal movement of ilium. B, Cephalad movement of ilium with caudal movement of sacrum. C, Anterior movement of sacrum on ilium (left side demonstrated).

To test each of these movements, the patient is in the prone position. For the first joint play movement, the examiner places the heel of one hand over the iliac crest and the heel of the other hand over the apex of the sacrum. The ilium is pushed down or caudally with one hand while the sacrum is pushed up or cephalad with the other hand. The test is repeated for the other ilium (see Figure 10-58, A). The examiner should feel only minimal movement, and there should be no pain in the joint if the joint is normal. In an affected sacroiliac joint, there is usually pain over the joint and little or no movement. This positioning tests for cephalad movement of the sacrum and caudal movement of the ilium.

To test caudal movement of the sacrum and cephalad movement of the ilium, the examiner places the heel of one hand over the base of the sacrum and the heel of the other hand over the ischial tuberosity (see Figure 10-58, B). The examiner then pushes the pelvis cephalad and the sacrum caudally. The test is repeated with the other half of the pelvis being moved. The movement and amount of pain are compared.

The anterior movement of the sacrum on the ilium is tested with the patient lying prone (see Figure 10-58, C). The examiner places the heel of one hand over the sacrum and places the other hand under the iliac crest in the area of the ASIS on one side. The hand is then pushed down on the sacrum while the other hand lifts up. The process is repeated on the other side, and the results are compared. Similarly, with the patient supine, a wedge may be used against the sacrum with the patient’s body weight acting to push the sacrum forward.

Lee5,62 has advocated a way to test other translations at the sacroiliac joint. The patient lies supine with the hips and knees in the resting position. The examiner palpates the sacral sulcus just medial to the PSIS with the middle and ring fingers of one hand, and the lumbosacral junction with the index finger of the same hand (Figure 10-59). The middle and ring fingers monitor movement between the sacrum and innominate (ilium) bone while the index finger notes movement between the sacrum and L5.

To test anteroposterior translation of the ilium on the sacrum, the examiner, using the other hand, applies pressure through the iliac crest and ASIS. Posterior movement of the ilium should be noted and end range is achieved at the sacroiliac joint when the pelvis is felt to rotate or move at L5–S1 (Figure 10-60). The motion is compared with the other side.

To test superoinferior translation of the innominate (ilium) bone on the sacrum, the examiner applies a superior force through the ischial tuberosity (Figure 10-61). The end of motion is reached when the pelvic girdle is felt to laterally bend beneath L5–S1. The motion is compared with the opposite side.

To test inferoposterior translation of the innominate on the sacrum, the examiner, using the heel of the other hand, applies an anterior rotation force to the ipsilateral ASIS and iliac crest (Figure 10-62). This produces an inferoposterior glide at the sacroiliac joint and is associated with nutation of the sacrum.

To test superoanterior translation of the innominate on the sacrum, the examiner, using the heel of the other hand, applies a posteriorly rotating force to the ipsilateral ASISs and iliac crest (Figure 10-63). This produces a superoanterior glide at the sacroiliac joint and is associated with counternutation of the sacrum.

An unstable sacroiliac joint has a softer end feel, increased translation, and possible production of symptoms.62

Superoinferior Translation of Symphysis Pubis.5

The patient lies supine. The examiner places the heel of one hand on the superior aspect of the superior ramus of one pubic bone and the heel of the other hand on the inferior aspect of the superior ramus of the opposite pelvic bone. A slow steady inferior force is applied with the uppermost hand while a superior force is applied with the lower hand (Figure 10-64). The examiner is testing the end feel and looking for the production of symptoms.

Palpation63

Because many structures are included in the assessment of the pelvic joints, palpation of this area may be extensive, beginning on the anterior aspect and concluding posteriorly. While palpating, the examiner should note any tenderness, muscle spasm, or other signs that may indicate the source of pathology.

Anterior Aspect

The following structures should be carefully and thoroughly palpated (Figure 10-65).

A, Anterior view. B, Posterior view.

Iliac Crest and Anterior Superior Iliac Spine.

The palpating fingers are placed on the iliac crests on both sides and gently moved anteriorly until each ASIS is reached. “Hip pointers” (crushing or contusion of abdominal muscles that insert into iliac crest) may result in tenderness or pain on palpation of the iliac crest—as may undisplaced fractures. The inguinal ligament attaches to the ASIS and runs downward and medially to the symphysis pubis.

McBurney’s Point and Baer’s Point.

The examiner may then draw an imaginary line from the right ASIS to the umbilicus. McBurney’s point lies along this line approximately one third of the distance from the ASIS and is especially tender in the presence of acute appendicitis. Baer’s point is located in the right iliac fossa anterior to the right sacroiliac joint and slightly medial to McBurney’s point. It is tender in the presence of infection or when there are sprains of the right sacroiliac ligament and indicates spasm and tenderness of the iliacus muscle.

Lymph Nodes, Symphysis Pubis (Pubic Tubercles), Greater Trochanter of the Femur, Trochanteric Bursa, Femoral Triangle, and Surrounding Musculature.

The examiner returns to the ASIS and gently palpates the length of the inguinal ligament, feeling for any tenderness or swelling of the lymph nodes or possible inguinal hernia. At the distal end of the inguinal ligament, the examiner comes to the pubic tubercles and symphysis pubis,64 which should be palpated for tenderness or signs of pathology.

The examiner then places the thumbs over the pubic tubercles and moves the fingers laterally until the bony greater trochanter of the femur is felt. The trochanters are usually level. The trochanteric bursa lies over the greater trochanter and is palpable only if it is swollen.

Returning to the ASIS, the examiner can move on to palpate the femoral triangle, which has as its boundaries the inguinal ligament superiorly, the adductor longus muscle medially, and the sartorius muscle laterally. It is in the superior aspect of the triangle that the examiner palpates for swollen lymph nodes. The femoral pulse can be palpated deeper in the triangle. Although almost impossible to palpate, the femoral nerve lies lateral to the artery, whereas the femoral vein lies medial to it. The psoas bursa may also be palpated within the femoral triangle, but only if it is swollen. Before moving on to the posterior structures, the examiner should determine whether the adjacent musculature—the abductor, flexor, and adductor muscles—shows any indication of pathology (e.g., muscle spasm, pain).

Posterior Aspect

To complete the posterior palpation, the patient lies in the prone position, and the following structures are palpated.

Iliac Crest and Posterior Superior Iliac Spine.

Again, the examiner places the fingers on the iliac crest and moves posteriorly until they rest on the PSIS, which is at the level of the S2 spinous process. On many patients, dimples indicate the position of the PSIS.

Ischial Tuberosity.

If the examiner then moves distally from the PSIS and down to the level of the gluteal folds, the ischial tuberosities may be palpated. It is important that they be palpated, because the hamstring muscles attach here and the bony prominences are what one “sits on.”

Sacral Sulcus and Sacroiliac Joints.

Returning to the PSIS as a starting point, the examiner should palpate slightly below it on the sacrum adjacent to the ilium. (This area is sometimes referred to as the sacral sulcus.) The depth on the right side should be compared with that on the left side. If one side is deeper than the other, sacral torsion or rotation on the ilium around the horizontal plane may be indicated.

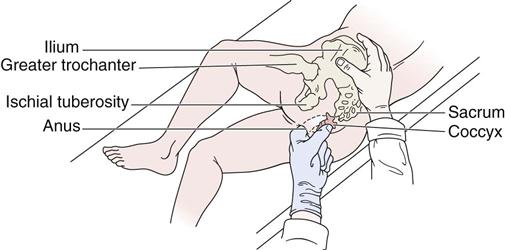

If the examiner then moves slightly medially and distal to the PSIS, the fingers rest adjacent to the sacroiliac joints. To palpate these joints, the patient’s knee is flexed to 90° or greater, and the hip is passively medially rotated while the examiner palpates the sacroiliac joint on the same side (Figure 10-66). This procedure is identical to the prone gapping test previously described in the “Passive Movements” section. The procedure is repeated on the other side, and the two results are compared.

Sacrum, Lumbosacral Joint, Coccyx, Sacral Hiatus, Sacral Cornua, and Sacrotuberous and Sacrospinous Ligaments.

The examiner again returns to the PSIS and moves to the midline of the sacrum, where the S2 spinous process can be palpated.

Moving superiorly over two spinous processes, the fingers now rest on the spinous process of L5. As a check, the examiner may look to see if the fingers rest just below a horizontal line drawn from the high point of the iliac crests. This horizontal line normally passes through the interspace between L4 and L5. Having found the L5 spinous process, the examiner then palpates between the spinous processes of L5 and S1, feeling for signs of pathology at the lumbosacral joint. Moving laterally approximately 2 to 3 cm (0.8 to 1.2 inches), the fingers lie over the lumbosacral facet joints, which are not palpable. However, the overlying structures may be palpated for tenderness or spasm, which may indicate pathology of these joints or related structures. In a similar fashion, the spinous processes and facet joints of the other lumbar spines and intervening structures can be palpated.

The examiner then returns to the S2 spinous process or tubercle. Carefully palpating farther distally (just before the coccyx), the examiner may be able to palpate the sacral hiatus lying in the midline. If the fingers are moved slightly laterally, the sacral cornua, which constitute the distal aspect of the sacrum, may be palpated (Figure 10-67).