Pelvic floor treatment of incontinence and other urinary dysfunctions in men and women

BEATE CARRIÈRE, PT, CAPP, CIFK

After reading this chapter the student or therapist will be able to:

1. Discuss factors that lead to incontinence.

2. Understand the neurophysiology involved in pelvic floor dysfunctions.

3. Describe the different layers of the pelvic floor and their functional connections.

4. Understand the importance of coordinating diaphragmatic breathing with pelvic floor activity.

5. Correct faulty breathing patterns to facilitate normal pelvic floor activity.

6. Apply motor learning and motor control principles when teaching exercises.

7. Select the most appropriate intervention to improve pelvic floor function.

Overview of the clinical problem

History of pelvic floor exercises

A different focus on how to view the pelvic floor and the problem of incontinence has evolved from new knowledge about neurophysiology, neuroplasticity, motor learning, motor control, and functional brain imaging.1,2 Kegel3–5 is considered the great American pioneer who, in the late 1940s, recognized the importance of exercises to help women with urinary incontinence (UI). Dr. Kegel, a Los Angeles physician, found that many women did not have any awareness of the function of the pelvic floor and that they were not always successful with the exercise he prescribed, which is drawing in the perineum. He therefore developed a pneumatic apparatus, the perineometer, which measured each muscle contraction in a manner visible to the patient. He instructed his patients to perform the exercise for 20 minutes three times daily, or a total of 300 contractions, and suggested weekly visits for instruction.3,4 Kegel also recognized that evidence of bladder weakness was present in some women before childbearing and emphasized the importance of training the pubococcygeus muscle to achieve continence.4,5 Considered visionary at that time, his approach to exercises demonstrates visual feedback combined with declarative learning. However, the treatment has not changed much since.6–9 Kegel exercises are stereotypical and highly repetitive (300 repetitions until improvement, then 80 per day for life) with little functional value. More recent studies have investigated the effectiveness of Kegel’s exercises.

Prevalence of urinary incontinence

The prevalence of UI in men and women is high and costly. Mardon and colleagues,10 who conducted a study of managed care beneficiaries, found the overall incidence of UI to be consistent with previous estimates. Fantl and colleagues11 reported in 1996 that 10% to 35%, or 13 million adult Americans, have UI. In 2000 Hu and co-workers12 estimated that 17 million community-dwelling persons had daily UI and 34 million had overactive bladder (OAB) syndrome, with 2.9 million of those reported to have had incontinence episodes.

In 1996 more than half of the 1.5 million nursing home residents in the United States were estimated to be incontinent. This condition is reported to be the most common reason for placing a family member in a home.11–13 The number of adults in institutional care had risen to 1.89 million in 2000, and 945,000 of those were estimated to have UI.12 Women older than 60 years have twice the prevalence of incontinence as men of that age.11 The majority of patients with incontinence are parous women and older persons.13 Goode and colleagues14 report that UI is a common geriatric syndrome affecting at least one in three older women. “UI is not a normal result of aging, it is a medical problem that is often curable and should be treated.”15 Britton and co-workers16 conducted a study of urinary symptoms in 578 men older than 60 years. Thirty percent of the men reported increased daytime frequency, and 27% reported urgency and a variety of other urinary symptoms, defined as OAB if nocturia (getting up at least once in the night to urinate) is included. Incontinence can also be found in the younger population. Nygaard and colleagues17 investigated UI in nulliparous elite athletes and found that individuals who participate in gymnastics and sports that include jumping, high-impact landings, and running appear to score higher in the prevalence of UI than those who swim or play golf. Because exercises and activities during field training of soldiers can be strenuous, one third of 450 female soldiers experienced UI according to Sherman and Davis.18 Baumann and Tauber19 reported that 17% of boys aged 5 to 14 years are incontinent. Adedokun and Wilson20 and Diokno and colleagues21 provided thorough epidemiological overviews, collecting data from various sources all over the world.

Risk factors for incontinence include the following:

Obesity: This is a risk factor and can contribute to incontinence and make the treatment more difficult.22,23

Cigarette smoking: Smoking augments incontinence for three reasons: (1) it has been shown to interfere with collagen synthesis, (2) neuromuscular and anatomical changes likely occur from smoking that result in decreased functionality of the bladder, and (3) it causes coughing, which increases the strain on the weak pelvic floor muscles.24 Moreover, cigarette smoking has been linked to erectile dysfunction and has an effect on sperm quality in men. In women, it is related to increased incidence of miscarriage and cervical cancer and reduced chance of conception.25 It has been reported that smoking cessation, weight reduction, and regulation of bowel movements may reduce the risk of UI.26

Diabetes: Hunter and Moore27 state that an estimated 13% of seniors have diabetes. Of these individuals, 32% to 45% have associated bladder dysfunction. The presence of UI in diabetics can be attributed to decreased bladder sensation, increased bladder capacity, and impaired detrusor contractility. Lee and colleagues28 studied voiding patterns in women with type 2 diabetes and stated that peripheral neuropathy was an important factor associated with diabetic voiding dysfunction. They found that patients with diabetes had predominantly nocturia and a weak urinary stream, abnormal nocturnal urine production, and decreased voiding volumes and functional bladder capacity. In the same study, researchers noted impaired detrusor contractility, with 13.9% of 194 female patients having high postvoiding residual (PVR) urine of over 100 mL. The researchers suspected that the dysfunction in detrusor contractility was secondary to diabetes. Moreover, 14.4% of the women in the study had less than 70% efficiency of emptying the bladder.

Neurologic diseases associated with UI include the following:

Brain injuries: Leary29 investigated incontinence after brain injury and reported that 50% of the patients had impaired bladder and bladder subscores on admission. Even though 90% of those patients were set goals for self-care and mobility, only 3.5% of the patients were set multidisciplinary goals addressing bladder and bowel function. The Agency for Health Care Policy and Research30 reported that UI is most prevalent in persons with spinal cord injuries (SCIs) and people with multiple sclerosis (MS). Eighty percent of patients with SCI will have had at least one urinary tract infection (UTI) by their sixteenth year postinjury.

MS: Seventy percent to 90% of individuals diagnosed with MS develop bladder dysfunction, which places them at high risk for UTIs (Agency for Health Care Policy and Research). McClurg and colleagues31 state that in patients with MS, bladder storage problems often coexist with inadequate emptying of the bladder because of detrusor sphincter dyssynergy. In their research with 30 patients with MS, they showed that a combined treatment of pelvic floor training and advice combined with electromyography biofeedback and neuromuscular electrical stimulation may reduce urinary symptoms in these patients. Schulte-Baukloh and colleagues32 injected 11 women and five men with MS and drug-resistant OAB symptoms with botulinum toxin type A and found significant improvement for 4 weeks to 3 months (but not at 6 months), with reduction in frequency, nocturia, and pad use; however, buildup of residual urine remained a problem.

Spina bifida: Patients affected by spina bifida also can have various neurogenic urinary tract dysfunctions. Depending on the severity of the dysfunction, they may become socially dry with conservative therapy.33

Alzheimer disease: In patients with Alzheimer disease cognitive and central regulating mechanisms contribute to incontinence.34 According to Holstege,1 research has shown that “lesions in the pathway from prefrontal cortex and limbic system, to the PAG (periaqueductal gray) probably cause urge incontinence in the elderly.”

Cerebrovascular accident (CVA): Brittain and colleagues35 state that UI after a stroke is associated with poor outcome and depression in stroke survival and care. The overall prevalence of UI is high (32% to 79%) in older patients with stroke admitted to the hospital. At discharge the incidence of UI is 25% to 28%, and 12% to 19% continue to experience UI for months after the stroke. The inability to communicate, transfer, or walk and the use of drugs complicate matters. UI in stroke patients is similar to UI in patients without stroke and probably results from muscle weakness on the affected side. The patients may demonstrate stress UI (SUI), but urgency UI (UUI) and mixed incontinence are also common. Studies published from 1985 to 1997 suggest that 31% to 40% of hospitalized stroke patients have fecal incontinence on admission and 18% at discharge, and 7% to 9% still experience fecal incontinence 6 months after the stroke.36 Unfortunately, treatment for these problems is rarely prescribed, even though it is very effective.37

Parkinson disease: In individuals with Parkinson disease, the prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTSs) is 27% to 39%, most frequently nocturia (86%); 71% of patients have reported frequency, and 68% have reported urgency. According to a study by Winge and colleagues,38 the patients were bothered most by the urgency symptoms. The authors inferred that the reason could be a progression of gait difficulties, decreased ability to separate and integrate sensory input, or both at a later stage of the disease. Zein and colleagues39 agreed with increased incidence of voiding dysfunction with the progression of the disease. They also describe incomplete emptying (40%) and hesitation (37.3%) as problems in their prospective study of 110 patients with Parkinson disease. Fowler and Griffiths2 suggest that the pathways from the PAG to the thalamus and insula do not conduct signals properly in Parkinson disease. Deep brain stimulation can restore the conduction.

Parkinsonian syndrome: Multiple system atrophy (MSA) is described in detail by Yamamoto and colleagues39a and Wenning and colleagues,39b who state that the clients have autonomic, cerebellar, and extrapyramidal symptoms. The syndrome presents as a more severe form of Parkinson disease and includes MSA, idiopathic Parkinson’s, vascular parkinsonism, and supranuclear palsy. Clients with MSA can have severe blood pressure variations and sudden orthostatic hypotension secondary to autonomic system problems in addition to more severe bladder dysfunctions such as higher incidence for urinary urgency, retardation in initiating urination and incomplete emptying of the bladder that may require catheterization. Prolongation of urination and constipation are also more common in MSA clients than those with Parkinson disease. The physical treatment has to address more symptoms and it is more complex and more difficult to improve the client’s quality of life.

Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS): The prevalence and mechanism of bladder dysfunction were evaluated by Sakakibara and colleagues.40 In their study of 65 consecutive patients urinary dysfunction was observed in 27.7%. Of those patients, 9.2% experienced retention, 24.6% had voiding difficulties, and 7.7% complained of urgencies. Overactive and underactive detrusor activity were the major urodynamic findings. The underlying mechanism, according to the authors, appeared to involve hypoactive and hyperactive lumbosacral nerves.

Cost of incontinence

Wilson and colleagues41 state that the cost for women over 65 years of age with UI is twice that for women younger than 65 years. Affecting 17% to 55% of community dwellers and up to 50% of nursing home residents, UI is one of the most prevalent chronic diseases. Only one-quarter to one-half of affected individuals seek medical attention. Within a 10-year period the direct cost increased considerably, more than could be accounted for by medical inflation. Hu and colleagues12 adjusted and reported the cost of UI and OAB syndrome in 2000: $19.5 billion and $12.6 billion, respectively. Thirty-four million individuals had OAB syndrome, and 17 million had UI. Because individuals with OAB have fewer incontinence episodes, the per-person cost is higher in patients with UI—35% of patients with UI have SUI, which can involve expensive surgeries. However, the days spent in the hospital have declined since 1995.12 The cost of UI escalated from $8.2 billion in 1984 to $16.4 billion in 1993 and to $26.3 billion, or $3565 per individual with UI, in 1995. Wagner and Hu42 attributed this increase to the following three major changes in the previous 10 years:

Definition of incontinence

UI is defined as involuntary loss of urine.43 Incontinence can have one or more causes, and in more than 90% of cases it can be improved or cured.13 Treatment should be instituted only after a careful, thorough history and physical examination.13

SUI is defined as involuntary loss of urine on effort or physical exertion, for example, sporting activities or sneezing or coughing.43

UUI is considered to be involuntary loss of urine associated with urgency.43

Mixed UI is the complaint of involuntary loss of urine associated with urgency and also with effort or physical exertion, sneezing, or coughing.43

Symptoms associated with bladder storage disorders include the following:

Increased daytime urinary frequency: Micturition (emptying of the bladder) occurs more frequently during waking hours than previously deemed normal by the patient.43

Nocturia: Patient wakes up from sleep one or more times because of the need to micturate. Each void is preceded and followed by sleep.43

Urgency: A sudden, compelling desire to pass urine that is difficult to defer.43

OAB syndrome: Cluster of symptoms of urinary urgency, usually accompanied by frequency and nocturia in the absence of UTI.43

Symptoms associated with voiding disorders include the following:

Hesitancy: Delay in initiating micturition43

Straining to void: A need to make an intensive effort to either maintain or improve the urinary stream43

Feeling of incomplete bladder emptying: Report that the bladder does not feel empty after micturition43

Urinary retention: Inability to pass urine despite persistent effort43

In patients with nonneurological conditions, the most common forms of incontinence are SUI, OAB syndrome, UUI, and mixed incontinence. Weak pelvic floor muscles usually cause SUI. SUI occurs when the abdominal pressure is greater than the urethral pressure, resulting in a loss of urine with coughing, laughing, sneezing, lifting, and so forth. OAB syndrome, or detrusor overactivity, is associated with involuntary bladder muscle contraction during the filling phase, causing frequent urination; nocturia; and strong, sudden, and sometimes unpredictable urges to urinate but not always resulting in incontinence.44

Etiology

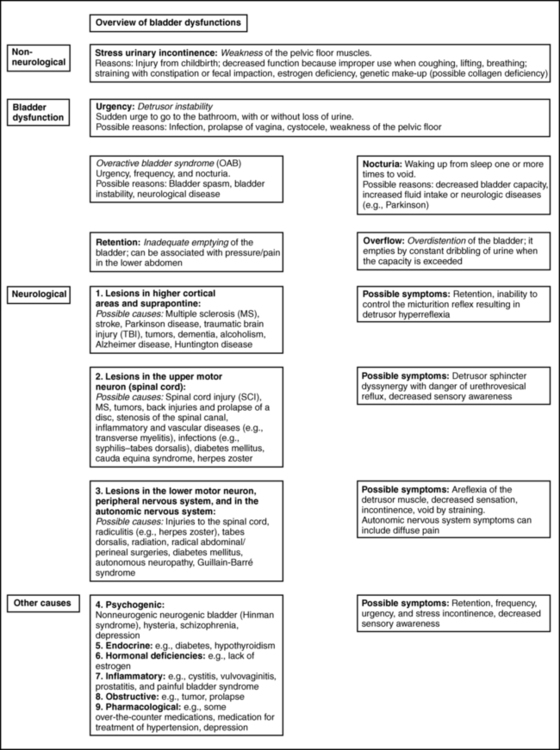

The causes of SUI and UUI in individuals with nonneurological conditions are as follows (Figure 29-1):

1. Functional causes include the inability to undress in a timely fashion and not being able to reach the bathroom in a timely fashion because of obstacles (e.g., no light, cannot enter the bathroom with the walker without maneuvering).

2. Weakening of the pelvic floor structures can result from childbirth (overstretching of muscles, injuries to the pudendal nerve, or ligaments), hysterectomy, prolapse (rectocele, cystocele, vaginal prolapse), straining with constipation, poor biomechanics when lifting, falls on the buttocks with shift of the pelvis affecting muscle length or stretching the nerves, and poor coordination of the pulmonary diaphragm with the pelvic floor, back, and abdominal muscles.45,46 Scars in the perineal and pelvic area, aging (loss of muscle mass), obesity, smoking, poor posture, and pain in the pelvic area also can contribute to muscle weakness.

3. OAB syndrome and UUI can be caused by UTIs and other conditions that irritate the bladder: neoplasia, post–bladder or post–bowel surgery status, bladder outlet obstruction, anxiety, nervousness, and poor toileting habits. The condition can also be idiopathic. Some clients also have urgency to eliminate the bowels.

4. Over-the-counter medications with anticholinergic agents can cause retention (an inability to empty the bladder completely), overflow (leakage of urine when the bladder is overextended), and frequency; antipsychotic medications can cause sedation, rigidity, and immobility; and diuretics can worsen impaired continence. Medication for treatment of hypertension can also contribute to incontinence.11,13,27,47,48

5. Retention in nonneurological clients can occur in men with prostate problems; the enlarged prostate makes the passage of urine difficult.16,49 Other causes in men and women are the hyperactive pelvic floor syndrome (HPFS),50 an inability to relax the pelvic floor muscles. This can be caused by pelvic pain syndromes, by painful bladder syndrome (formerly interstitial cystitis), or by habits: trying to void in a hurry, squeezing rather than relaxing the muscles, and being unable to void because of stressful situations.

6. An overdistended bladder can cause overflow incontinence. It can manifest as constant or intermittent dribbling, sometimes combined with urgency or symptoms of stress incontinence. Patients often have high residual urine levels and feel that their bladder does not empty properly; sometimes secondary to sensory problems, the patients are unaware of the filling of the bladder.

7. Inadequate fluid intake (either too much or too little) and fluids that may be stimulants to the bladder can cause urgency incontinence or frequent trips to the bathroom. Smoking, obesity, and postmenopausal estrogen deficiency contribute to the problem.11,22,24,47,48

Neurogenic causes of bladder dysfunctions are as follows:

1. Lesions in the higher cortical areas and suprapontine lesions can be found in patients with MS, stroke, Alzheimer disease, Parkinson disease, traumatic brain injury, tumors, and dementia. Lateral prefrontal cortex activation probably regulates the desire to void and to remain continent.2 Lesions in the pathways from the prefrontal cortex and limbic system to the PAG probably cause urgency incontinence in the elderly.1 The emotional motor system (EMS) uses the cell group of the pontine micturition center (PMC), close to the locus coeruleus, which sends long descending fibers to the parasympathetic motoneurons to the sacral cord. Through inhibitory interneurons, fibers reach the nucleus of Onuf. Stimulation of the PMC therefore results in complete micturition.1 Neurological diseases can cause many other symptoms such as retention and an inability to control the micturition reflex. Detrusor hyperreflexia (overactive detrusor during the filling phase) with coordinated urethral relaxation interferes with normal tonic inhibition of the parasympathetic pathways and the balance between facilitatory and inhibitory mechanisms in the PMC.44,47,48,51

2. Lesions in the upper motor neurons (UMNs) affect the spinal cord. Common problems resulting in urinary dysfunction are SCI, MS, cauda equina syndrome, tumors, inflammatory diseases such as transverse myelitis, infectious diseases such as syphilis (tabes dorsalis), injuries to the spinal column, prolapse of a disc, or stenosis of the spinal canal. A typical bladder problem is detrusor hyperreflexia without coordinated urethral relaxation (detrusor-sphincter dyssynergy).47,48,51,52

3. Lesions of the peripheral or lower motor neurons (LMNs) such as injuries from childbirth, traumatic injuries, diabetes, radiculitis (e.g., from herpes zoster), or tabes dorsalis can cause retention and detrusor areflexia. The inability to feel when the bladder is full can lead to an overflow bladder with symptoms of dribbling and incomplete or strained voiding. Patients may need to learn clean intermittent catheterization.11,13,48,51,53

4. Lesions stemming from injuries to the autonomic nervous system can be caused by surgery in the pelvic area, such as hysterectomy, rectum resection, and radical prostatectomy; injury; or inflammations such as chronic cystopathy in diabetic patients. Autonomic lesions can contribute to diffuse pain,54 swelling, and altered sensory awareness. Patients with urinary problems can describe the feeling of having cold feet.55,56 Patients with diabetic cystopathy (DC)—in addition to their symptoms of weak stream, hesitancy in starting urination, dribbling, and overflow from high residual urine levels (caused by decreased bladder sensation and increased bladder capacity, and impaired contractility)—may also have other symptoms of autonomic dysfunction. These can include orthostatic hypotension, nocturnal fall of blood pressure, and changes in heart rate.7,27 Altered central nervous system (CNS) monoamines (serotonin and noradrenaline) can cause both depression and OAB. Correction of some neurologic disorders can eliminate both depression and urgency incontinence.57

5. Psychogenic causes of urinary dysfunction include schizophrenia and depression. Patients can experience incontinence, hesitation, retention, and pain.

6. A nonneurogenic neurogenic bladder is called Hinman syndrome.47

7. Endocrine causes are hypothyroidism and diabetes, which may lead to a flaccid or areflexic bladder and require clean intermittent self-catheterization.47,53 Diabetes can also increase the frequency of urination.

Anatomy and physiology of the pelvic floor

The pelvic floor consists of all the muscles that close the pelvic cavity. It is part of the abdominal compartment that can be defined by the pulmonary diaphragm cranially, the pelvic diaphragm and perineal membrane caudally, the muscles of the abdominal wall ventrally, and the muscles of the back dorsally. This compartment houses the internal organs and the viscera.13,45–47,58–61 All muscles of the abdominal compartment interact and support one another, providing postural stability and the ability to breathe, talk, and eliminate. The pelvic floor is essentially composed of three layers: the endopelvic fascia, the pelvic diaphragm, and the perineal membrane.

Endopelvic fascia

The endopelvic fascia suspends and supports the organs within the pelvis. It is a mesh of connective tissue composed of collagen, elastin, blood and lymph vessels, and nerves. A thick, fibrous part of the endopelvic fascia, the pubocervical fascia, attaches to the cervix in a slinglike fashion and assists in supporting the urethra and the bladder. Laterally it connects to the fascia white line, the tendinous arch of the levator ani muscle. Injuries to this important fascial support can contribute to weakness of the pelvic floor, prolapse, and leakage with increased abdominal pressure.13,48,61 One study62 has shown that fascia may be able to contract in a smooth muscle-like manner and therefore may have the ability to influence musculoskeletal dynamics. This underlines the importance to not neglect the fascial structures surrounding the abdomen when treating pelvic floor dysfunctions. They are not purely passive structures.

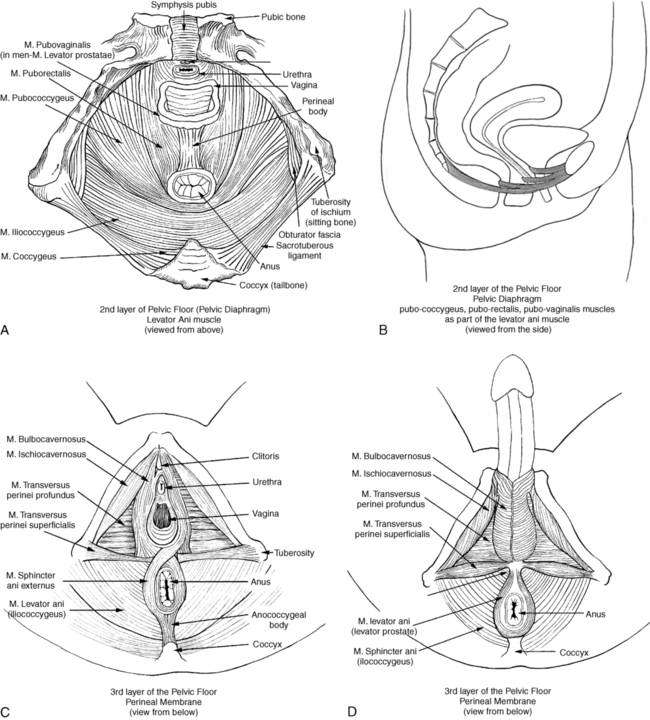

Pelvic diaphragm

The pelvic diaphragm consists mostly of the paired levator ani muscle (Figure 29-2). The levator ani is shaped like a hammock and has several parts. In the sagittal plane the muscle originates at the pubic bone and attaches to the coccyx, hence the name pubococcygeus muscle. The medial part of the pubococcygeus joins behind the rectum and therefore is named the puborectalis muscle. This part of the levator muscle provides continence of bowel by increasing the anorectal angle. Inability to relax the puborectalis therefore contributes to constipation in patients with HPFS. Other fibers of the levator ani form a sling around the vagina or prostate (pubovaginalis and levator prostate muscles). Each side of the muscle meets in the midline with the other half and attaches to the perineal and anococcygeal bodies. The compressor urethrae muscle is part of the external urethral complex. It originates from the rami of the ischium and pubis and runs fanwise forward and medially to arch over the anterior part of the urethral surface. The sphincter urethrovaginalis is part of the puborectalis.63

The posterior part of the levator ani has two paired sections. The coccygeus (or ischiococcygeus) muscle covers the sacrospinous ligament. The muscle arises at the spine of the ischium and extends to the lowest part of the sacrum and the coccyx. The iliococcygeus lies between the coccygeus and the puborectalis and passes in a diagonal direction between the coccyx to the spine of the ischium and the tendinous arch of the levator ani. This fibrous band of the arcus tendineus is suspended between the pubic bone and ischial spine.13,47,48,61,63–65 The levator ani is a skeletal muscle with a high resting tone; it consists of approximately 70% slow-twitch fibers and 30% fast-twitch fibers.48,61,66–68 Wall and colleagues48 and Bump and colleagues66 consider the high resting tone critical for pelvic support and for keeping the hiatus of the levator closed. Because the levator ani muscle is under voluntary control, it can be actively contracted and provide closure during an increase in abdominal pressure, such as when coughing or sneezing.48,67–69 According to Retzky and Rogers,13 the innervation of the levator ani muscles is under dual control: on the pelvic surface by motor efferents of the sacral nerve from S2 to S4, and on the perineal surface by the pudendal nerve.

Perineal membrane

The perineal membrane (formerly urogenital diaphragm) is the outer layer of the pelvic floor. It is a thick, fibrous, and muscular layer of triangular shape immediately below the levator ani. In women the perineal membrane attaches the edges of the vagina to the ischiopubic ramus; in men it forms an uninterrupted sheet of tissue. The fibers of the deep and superficial transverse perineal muscles run primarily in a frontal plane and contain many fibrous tissues,70 the ischiocavernosus muscle in a diagonal direction, and the bulbospongiosus muscle in a sagittal plane. The external sphincter muscle of the anus is part of the perineal membrane and is connected to the transverse perineal and bulbospongiosus muscle by the perineal body, which contains fibrous tissue. The dorsal attachment of the perineal membrane is achieved through the anococcygeal raphe, which connects the external anal sphincter (EAS) to the coccyx.48,64,67,70

The muscles of the perineal membrane include both smooth and striated muscles. The muscles become tight when the levator ani tone remains relaxed.48 The anterior portion of the perineal membrane is closely connected to the urethral musculature. According to Wall and colleagues,48 the perineal membrane does not substantially contribute to pelvic support; it is mostly the levator ani, which has much greater strength and bulk and can exert upward traction when contracting to maintain outlet support. The ischiocavernosus, bulbospongiosus, and superficial transverse perineal muscles function mainly in sexual responsiveness, serving to enhance and maintain penile erection in males and maintaining erection of the clitoris in females.48,61 Trigger points in these muscles can cause a degree of impotence and pain with intercourse. According to Claes and colleagues,71 Van Kampen and colleagues,72 and Dorey,73 strengthening exercises of the muscles of the perineal membrane can significantly improve impotence. In women the perineal membrane is often torn or injured during childbirth, and, if not properly repaired, injuries can cause sexual dysfunction, pelvic pain, and low self-esteem.

The complicated autonomic innervation of the pelvic area and its clinical relevance, including the perineal area, has been well described by Wesselmann and colleagues54 as well as Fritsch and Umphred.70 The pudendal nerve diverges from the sacral plexus, intermingles with the autonomic nerves, and then branches into several directions, innervating the EAS and the anterior perineal muscles.

Mucosal coaptation of the urethra

In addition to the three pelvic floor layers, an important contributor to continence is the mucosal coaptation, which is the arteriovenous complex between the epithelial lining and the smooth muscle coat of the female urethra. It is sensitive to estrogen, and with deficiency of this hormone the resting pressure of the urethra can decrease and cause leakage.13 Wall and colleagues48 compared it with an “inflatable cushion” helping to fill the urethral wall and sealing the 3- to 4-cm–long urethra in women. Because of possible serious side effects of estrogen treatment, it is now prescribed and applied to the vaginal area in low dosage and with caution. It can help some menopausal women increase the resting tone of the urethra and improve closure. The male urethra is not estrogen dependent. Its mucosal coaptation is highly vascular and probably influenced by testosterone. In addition, the prostate gland and the length of the male urethra may contribute to a sealing effect.

Internal sphincter of the urethra

The internal sphincter muscle at the junction of the bladder and urethra (urethrovesical junction) is an involuntary smooth muscle under autonomic control in both males and females. Its shape is circular and formed by the trigone, a smooth muscle in the bladder, and two U-shaped loops of muscles that derive from the bladder muscle. In females the urethra rests on a hammock of connective tissue (pubocervical fascia) and is held in a position that prevents descent into the vagina. The external sphincter muscle is able to close the middle portion of the female urethra.13

Incontinence usually happens when several factors come together. For example, men frequently leak after radical prostatectomy because the smooth internal sphincter urethra may have been damaged by the surgery and the pelvic floor muscles have to learn to substitute and provide closure of the urethra. A patient with dementia may not feel the need to go to the bathroom because of lesions in the limbic system or the cortex.1,2 Parkinson disease may cause bladder outlet obstruction because of a noncontractile detrusor, resulting in large volumes of residual urine or lack of activation of the PMC.2,74 In addition, the inability to quickly undress complicates an already existing problem of incontinence in such a client.

Voiding mechanism of the bladder

Many of the neurophysiological connections involved in functioning of the bladder and the surrounding muscles are not fully understood. A complicated coordination of many systems is involved in a properly functioning bladder and other pelvic organs. Elaboration on all the neural interactions, which take place at all levels, is not possible in this chapter. Wesselmann and colleagues54 and Burnett and Wesselmann75 provide comprehensive information about the neurobiology of the pelvis.

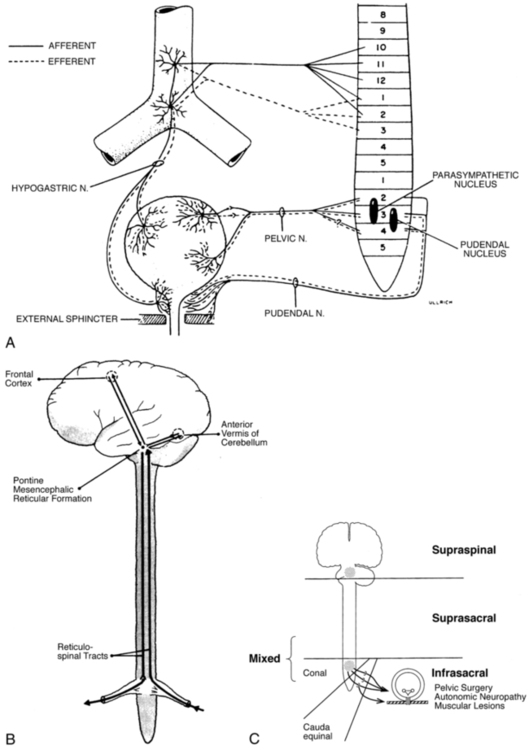

Sympathetic innervation

The sympathetic innervation to the bladder, rectum, and sexual organs originates from the thoracolumbar segment of the spinal cord (T10 to L1-L2) as well as from the hypogastric plexus (the sympathetic hypogastric nerve), which descends from the aortic plexus (Figure 29-3). The hypogastric nerve feeds into the inferior hypogastric (pelvic) plexus, which is the major neuronal integrative center for multiple pelvic organs.54,75 Both the sympathetic and parasympathetic divisions of the autonomic nervous system innervate the pelvic viscera, which are also innervated by the somatic and sensory nervous systems. The sympathetic innervation inhibits the bladder and increases bladder storage ability (it is sympathetic to be dry) and stimulates the muscles of the trigone and the internal sphincter muscles of the bladder as well as the muscles of the rectum. Attention should be paid to the T10 to L1-L2 segments in patients with tailbone pain and pain in the pelvic floor (e.g., testicular, buttock, scrotal pain) because the pain may be referred from that area. I recall a case in which tailbone pain disappeared instantly after treatment of the thoracolumbar area in a client who had fallen on the back in a flexed position. Doubleday and colleagues76 described a case of a patient who for 5 years had complained of testicular and buttock pain along with posterior leg paresthesias. Treatment of the T10 to L1-L2 area (central disk protrusion at T12-L1) with direct and guided physical therapy resulted in complete symptom resolution.

Parasympathetic innervation

The parasympathetic innervation exits the spinal canal at the level of S2 to S4. The nerves join the splanchnic nerve before entering the inferior hypogastric plexus (see Figure 29-3, A). The parasympathetic fibers stimulate the bladder and other pelvic organs, including the sexual organs.54,75,77 The parasympathetic fibers ending in the bladder are especially sensitive to overstretching, infection, and fibrosis.47 This explains the frequent urgency to urinate under such conditions. The parasympathetic nerve helps bladder contraction by stimulating muscarinic receptors in the fundus of the bladder. Parasympathetic nerve activation also helps colonic mobility. Therefore in an SCI when LMNs are injured (parasympathetic cell bodies in the cauda equina and conus medullaris), the result can be slowed stool propulsion with areflexic bowel. LMN injury causes constipation and increases the risk of incontinence from lax EAS, as described by Benevento and Sipski.52

In contrast an UMN lesion such as those from MS causes hyperreflexia with no voluntary control over the EAS. The patient cannot relax the EAS to defecate even though reflex coordination and stool propulsion are present. Urinary and fecal retention and constipation are common in such UMN injuries.52

Detrusor sphincter dyssynergia (DSD), caused by impaired coordination between bladder contraction and the external sphincter urethra, can be attributable to hyperreflexia or uncontrolled muscle spasm of the detrusor. This condition is common in patients with SCI52 as well as MS but not in clients with cerebral vascular accident (CVA).

Somatic innervation

The somatic innervation of the pelvic floor comes from the sacral plexus of S2 to S4 (see Figure 29-3, A). The pudendal nerve leaves the spinal cord at S2 to S4 and branches to innervate the striated muscles of the levator ani, the external sphincter muscles of both the urethra and rectum, the labia and clitoris, and the muscles of the perineal membrane. The sacral plexus provides both efferent and afferent innervation; some of the fibers of the pudendal nerve intermingle with the autonomic pelvic nerves.47,54,77 The somatic nerves can modulate the autonomic system. The complexity of the innervation of the pelvis and the influence of neurotransmitters in the bladder wall, as well as the control of higher CNS regulation (see Figure 29-3, B and C), can be appreciated in observing the filling and emptying phases of the bladder. Because of its topographical position the pudendal nerve is susceptible to nerve injury from stretching or compression (Alcock canal) from a fall on the buttocks or from slamming on the brake pedal during a motor vehicle accident (may alter pelvic alignment). Patients with pudendal nerve injury often have no problems when supine or standing but pain when sitting. Childbirth, especially during delivery of large babies, also can cause pudendal nerve injury.13

Sensory innervation

The sensory innervation in the pelvic region is important to evaluate and restore in clients with motor control problems because sensation drives motor responses. The pudendal nerve carries both sensory and motor fibers. Absence of feeling in the perineal area can be caused by stress and memory of pain (e.g., abuse). For example, a client with symptoms of incontinence and pain with sexual intercourse and a history of considerable continuous stresses stated after few treatments, “I thought my pelvic region was dead; I had no clue how little I could feel before sensory awareness training. Feeling the pelvic floor, I can now contract and relax the muscles much better.” Sensory innervation of the bladder comes primarily from proprioceptive nerve endings in the bladder and urethra. The afferent neuronal visceral system probably enters the spinal cord by way of the sacral and lumbar segments. These afferent nerve tracts may regulate pain, the absence of pain, and the feeling of having a full bladder.47,77

Filling and storage phase

The bladder is a smooth involuntary muscle with voluntary control. It stores the urine until it is emptied voluntarily. The normal bladder is a low-pressure system that accepts urine without a concomitant rise of internal pressure.13,48 This is produced by sympathetic stimulation of the β-adrenergic receptors in the bladder wall. The sympathetic nervous system inhibits the parasympathetic activity while sympathetic stimulation of the α-adrenergic receptors in the internal sphincter muscle causes constriction and a rise in urethral pressure.13,48 During the filling phase the bladder is inactive until it holds approximately 350 to 500 mL of urine, even though a first sensation of filling may occur with 150 to 250 mL of urine in the bladder.77 When the bladder is full the receptors send a signal to the cortical centers of the brain, and as a result a voluntary micturition reflex is initiated to empty the bladder (see Figure 29-3, B).13,48,77

Involuntary contractions of the detrusor during the filling phase cause frequency and urgency (OAB syndrome). In neurological patients this is called hyperreflexia; if idiopathic, it is considered bladder instability.47,48 Individuals with a hypersensitive bladder or painful bladder syndrome (interstitial cystitis) empty their bladders frequently to avoid pain, which results in a functionally small bladder. When the sensation of bladder filling is decreased or absent, the bladder will overfill and urine can back up into the kidneys, causing dysfunction. Symptoms of overflow from the overstretched bladder frequently cause dribbling. All these problems require thorough medical investigation of possible causes.

Preconditions for a normal storage phase as described by Henscher78 include good distensibility of the bladder, stable bladder without premature detrusor contractions (adequate bladder sensation, i.e., intact CNS and peripheral nervous system), no obstruction between kidney and bladder, and positive urethral closure at rest and under load.

Emptying phase

Micturition, or voiding, depends on the coordinated activity of the urethra and the detrusor muscle. The pelvic floor (levator ani and external sphincter muscles) has to relax when the detrusor muscle contracts. This occurs with activation of the parasympathetic cholinergic receptors in the bladder muscle. An afferent stimulus from the pelvic nerve (see Figure 29-3, A) reaches the PMC by way of the spinal cord. Efferent tracts inhibit the activity of the pudendal nerve, which results in relaxation of the external sphincter and levator ani. At the same time, sympathetic activity at the bladder neck is inhibited and postganglionic parasympathetic neurotransmitters are stimulated. This results in detrusor contraction.13,19,47,77

From the PMC, signals are also sent to the cerebral cortex, which allows voluntary control. An individual therefore can override the signal to empty the bladder and wait to empty it later or can empty the bladder when there is no signal that it is full. Suprapontine control of bladder function is a result of the modulating control of the brain stem, hypothalamus, and cerebral cortex.1,77

Many reflexes are involved in urine storage and voiding at various levels. The sacral reflex, for example, can be elicited by light stroking at the lateral aspect of the anus and should result in a symmetrical contraction of the anal sphincter (“anal wink”). Absence of the anal wink can be an indication of a neurological problem at S2 to S4, resulting in weakness or paralysis of the pudendal nerve.13 The micturition reflex, on the other hand, depends on an intact PMC in the brain stem.77

Prerequisites for a normal emptying phase include intact neural control, adequate functioning of the detrusor, no increase in resistance to voiding by obstruction, and adequate pelvic floor relaxation.78

Pharmacological treatment of pelvic floor dysfunction

The great number of receptors in the bladder wall, as well as the ability to influence skeletal muscles with muscle relaxants, is the basis for pharmacological treatment of the symptoms found in patients with incontinence. Other treatments for urinary dysfunction address hormonal deficiency. Estrogen, for example, was prescribed for many postmenopausal women with symptoms of leakage and a feeling of dryness in the vaginal area.13,47,48,51 However, treatment with oral estrogen is controversial, and reports of its efficacy for treatment of UI are mixed.26 Topical vaginal application of Premarin and other drugs may be beneficial in the treatment of UI because estrogen deficiency decreases the turgor of the submucosa around the urethra.

α-Adrenergic agents such as phenylpropanolamine or ephedrine increase striated muscle tone and are therefore used with SUI. α-Adrenergic antagonists, such as drugs for treatment of hypertension, can worsen incontinence. Caffeine, alcohol, and diuretics can increase urinary frequency, urgency, and SUI.11,13,47,79 Antipsychotic agents are also α-adrenergic antagonists and reduce urethral pressure and can be used for treatment of urinary retention.13 The problem with pharmaceutical treatment is the side effects, some of which may affect the pelvic floor adversely (e.g., constipation). Other clients describe severe dryness in the mouth and the need to drink or suck on candy constantly. Many other side effects have been described by the people taking these drugs, including dizziness, blurred vision, somnolence, confusion, hypertension or hypotension, and dryness of the mucosal membranes of the mouth, vagina, and eyes.27

Solifenacin succinate is an antimuscarinic agent that blocks muscarinic receptors on bladder smooth muscles, relaxing them. It is therefore indicated for relief of urinary frequency, urgency, and UI associated with OAB syndrome. Other commonly prescribed antagonists of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors include darifenacin, fesoterodine, oxybutynin, propiverine, tolterodine, and trospium.80

For clients with MS, anticholinergic medication is recommended for the treatment of neurogenic overactivity of the bladder. Intravesical treatments with vanilloids and botulinum toxin have been proposed, as well as sublingual cannabinoids. DasGupta and Fowler81 also state that sildenafil citrate has been shown to be efficacious as a proerectile agent. Sildenafil (Viagra) has been shown to be efficacious in men with SCI; it also may improve arousal in women with SCI and is being evaluated for female patients with sexual arousal disorder.82,83

Intravesical resiniferatoxin (an analog of capsaicin with more than 1000 times its potency in desensitizing C-fiber bladder afferent neurons) is a new therapy for detrusor hyperreflexia for SCI, MS, and other neurologically impaired patients.84

Examination, evaluation, and intervention

Medical evaluation

Before a referral to physical therapy, a physician, preferably a urologist or gynecologist, should evaluate a patient with any urinary dysfunction. The patient’s history will lead the physician to select appropriate diagnostic tests, including a urodynamic test, which helps explore the extent of the lesion, rule out causes that require other treatments, and determine if physical therapy may help.13,47,48 Adams and Frahm79 provide an excellent overview of the causes and the examination and intervention possibilities. Part of the evaluation process should be a bladder diary or voiding log completed over a several-day period (if possible including a weekend day) so that a clear picture emerges about fluid input and output as well as when frequency and incontinence episodes occur and to what extent. Patients can also weigh their pads or liners for 24 hours and that way get a clear picture of the loss of urine in 24 hours. Both “tests” can be repeated after a series of treatments to measure progress. If the physician has not done these tests, they should be included in the physical therapy evaluation.

Physicians should also include a muscle strength test of the levator ani when seeing a client with symptoms of UI to determine how much the muscle weakness contributes to the problem.48,67,79

Physical therapy examination

Usually, physical therapists trained in women’s health assess the muscle strength of the pelvic floor of their clients by digital internal palpation. This may not necessarily take place on the first visit, and the patient must consent to such an evaluation. Because of the danger of re-traumatization, internal examination and use of instruments in the vagina (such as biofeedback probes) should not be applied to clients who have been abused.85,86 Therapists should be reminded that such patients may say yes when they mean no because of their past experiences. It is possible to perform external palpations with the consent of the client and use other tests for evaluation of the extent of leakage and weakness with stress incontinence as described earlier, or the pad test, which can be performed by physicians or therapists.47,48,79,87

Conceptual framework for treatment

Therapy begins with a patient interview and appropriate tests and measures, which are necessary to determine which structures and systems are involved and what kind of impairment or activity limitations can be identified.8,88,89 The information gathered leads to the development of a diagnosis and prognosis and selection of the intervention and, hopefully, the most efficacious treatment outcome.

Evaluation of female clients with incontinence

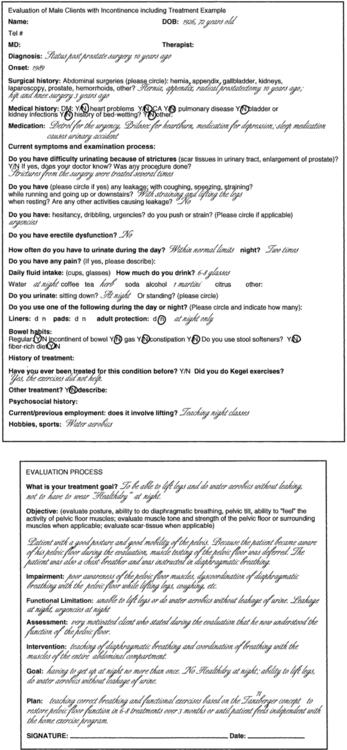

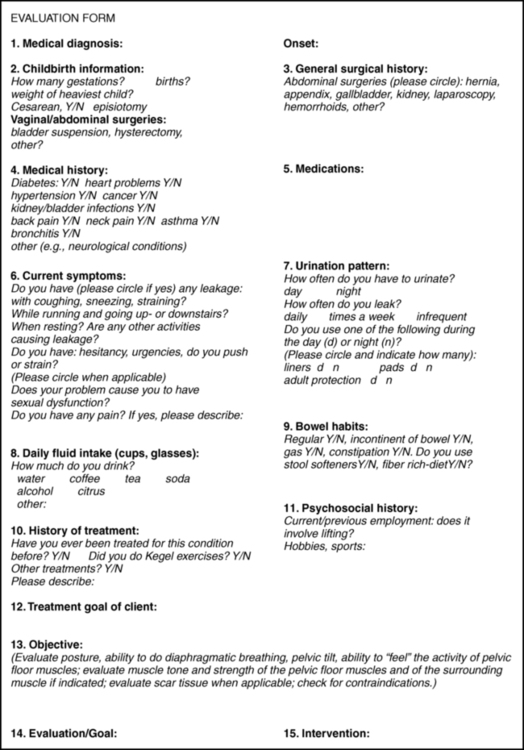

An example of an examination-evaluation process that might be used for female clients with incontinence is shown in Figure 29-4.

Evaluation form.

Evaluation form.Question 7

The pattern must be seen in light of the history and daily fluid intake. The information of the voiding diary should match the urinary pattern. Normal urination is six to eight times per day at a volume of at least 250 mL (9 oz), with a maximum of 500 mL. Many adults normally get up once a night to urinate; elderly people may need to get up twice each night.47

Question 9

Many reasons exist for constipation; it can be related to difficulty going to the bathroom at work, being always in a hurry, or not relaxing the pelvic floor because of improper leg support when sitting on the toilet.90 HPFS, eating hastily, and consuming constipating foods can contribute as well. Gastrointestinal problems, especially when combined with chronic pelvic pain or low back pain, can be the result of sexual abuse.91 Fecal incontinence can result from weakness of the anal sphincter muscle, occult injuries or tears from difficult deliveries, hemorrhoids, insufficient fiber intake, poor bowel habits, and so on.

Case studies

Case Studies 29-1 and 29-2 give insight into how physical therapy can help clients with incontinence. Before presenting another case study, the conventional treatment approach to incontinence is discussed briefly, and then the Heller and Tanzberger concepts92–98 are described in more detail.

Conventional treatment options for stress urinary incontinence, urgency urinary incontinence, mixed incontinence, and overactive bladder

Most therapists treating patients with incontinence are familiar with biofeedback, electrical stimulation, and vaginal cones, which are often used in combination with Kegel exercises. Kegel exercises have provided only limited success. Henalla and colleagues99 found that 65% to 69% of patients in two hospitals became dry or significantly improved with exercises only. Wall and Davidson68 stated that exercise programs have a place in the treatment of genuine SUI. Miller and colleagues69 demonstrated how tightening the pelvic floor muscles before a cough significantly diminished leakage from the bladder. Bø and colleagues100,101 found that intensive exercises taught by physical therapists over a long period provided better results, which was in agreement with a Danish study by Tilbæks.102 Meaglia and colleagues103 stated that motivation, close supervision, and encouragement are important for successful treatment. Holley and colleagues104 found that a great number of patients stopped exercising because of lack of motivation. Bø and colleagues105 found that intensive pelvic floor muscle training seen short-term was not maintained 15 years later. Bump and colleagues66 found that brief verbal instructions in Kegel pelvic floor muscle exercises were not sufficient. Byl and colleagues106 investigated the effect of repetitive movements (three to 400 trials per day) in skeletal muscle in primates compared with variable repetitive movements and found that the repetitive movements caused interference with motor control. Repetitive movements are also a problem in patients with focal dystonia. Stereotypical and nearly simultaneous movement causes problems in the brain.107,108 Variable trials preserved motor control. The question must be asked: Is performing Kegel exercises 300 times a day beneficial? The question is appropriate because these exercises train the muscle in isolation and not as part of a functional activity. Do individuals believe that Kegel exercises do not help and therefore discontinue them? Similarly, a therapist would not ask a client to perform isometric exercises of a skeletal muscle 300 times a day and continue 80 times a day for the rest of the client’s life once improvement became noticeable. This action does not seem any more appropriate if done with the pelvic floor muscles.

In a 1999 study by Salamey and Nof,109 approximately 72% of the questioned therapists stated that they felt prepared to instruct patients in pelvic floor (Kegel) exercises. Only 18% of therapists were prepared to discuss UI with their patients, and the majority were not prepared to perform electrical stimulation, biofeedback, or other conservative treatments. For many years Kegel exercises were what the majority of therapists learned in the United States as treatment for incontinence.

Biofeedback and electrical stimulation, as well as vaginal cones, are recognized treatments for SUI. They are used either in combination with exercises or alone.101,110–112 The effect of electrical stimulation alone on stress and urgency incontinence has been conflicting.101,113 Bø113 recommended its use only when a person is not able to contract the pelvic floor muscles and proposed continuing with the exercises when the individual is able to contract the pelvic floor muscles. Another study by Bø and colleagues101 found pelvic floor exercises to be superior to electrical stimulation, vaginal cones, and no treatment.

The OAB syndrome was first defined by the International Continence Society (ICS) in 2002. Abrams describes this bladder storage problem as a combination of urgency with or without loss of urine, frequency, and nocturia.114 Its prevalence is high, and it affects men and women. Twenty-four percent of men and 31% of women in a study by Temml and colleagues115 reported a negative impact of OAB on sexuality. Even though it is common to treat the patients with antagonists of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors, physical therapy is very beneficial, and treatment has to address all three symptoms and include bladder training.

Exercises based on the Klein-Vogelbach and the Tanzberger and Heller concepts, the most common form of exercises for incontinence and pelvic floor dysfunction taught in Germany,92–98,116–118 have been introduced and taught in a modified version in the United States by Carrière.119,120

The goal of the exercises is to integrate the function of the entire abdominal compartment as a procedural program.119 The exercises should teach patients fast and slow muscle fiber training, isometric, concentric and eccentric strengthening exercises, and relaxation of the pelvic floor muscles. Correct use of the pelvic floor muscles also requires restoration of diaphragmatic breathing, as does coordination with all muscles of the abdominal compartment. Hodges59 and Massery45,46,58 highlight the importance of integration of posture and breathing and treatment of all muscles of the abdominal compartment in order to restore the health of the pelvic floor. The Swiss ball allows for skill and coordination exercises and provides position to decrease the load of the pelvic floor muscles.

Restoration of proper diaphragmatic breathing

Every breath changes abdominal pressure. Forced exhalation increases the pressure; so do coughing and sneezing. Leaning forward or backward also changes abdominal pressure. Clients should learn to coordinate the contraction of the pelvic floor with changes of pressure. In addition, these activities cannot be done without the cooperation of the abdominal and back muscles. All abdominal muscles are important for posture and breathing.58,59 Exercises designed to restore pelvic floor function must therefore include coordination of all muscles involved. A great number of individuals with incontinence are chest breathers, possibly because of the poor habit of constantly pulling the stomach in to appear more slender. Restoration of diaphragmatic breathing is therefore the first priority for clients with incontinence.119,120

Better breathing patterns may also help provide more oxygen to the pelvic region. Knowing how to control breathing may help a client relax when nervous or anxious (Figure 29-6).

Sensory awareness of the pelvic floor

The pelvic floor muscles are in the shape of a hammock. Their resting tone is high, and relaxing the pelvic floor is required during urination and defecation as well as during delivery and sexual activity.67,70 Thus sensory awareness is an important aspect of retraining the pelvic floor muscles. For all individuals, activities such as coughing, sneezing, lifting, and sexual activity require contraction and relaxation of pelvic floor muscles. The ability to relax and contract these muscles is a problem for clients with incontinence. For individuals to regain this control and sensitivity within the pelvic floor, certain treatment protocols must be established.

First, a client can feel landmarks such as the coccyx, the pubic bones, and ischium. Sitting on a firm surface, the client can first contract the gluteal muscles, then relax them, then try to feel the contraction of the anal sphincter and the muscles around the vagina by imagining holding a small object with those muscles without activation of the gluteal muscles. Imagery of voluntary movements of fingers, toes, and tongue has been shown to activate the appropriate sections in the contralateral primary motor cortex.123 It is therefore probable that imagery of striated pelvic floor muscles would also activate sections in the primary motor cortex assigned to this body part.

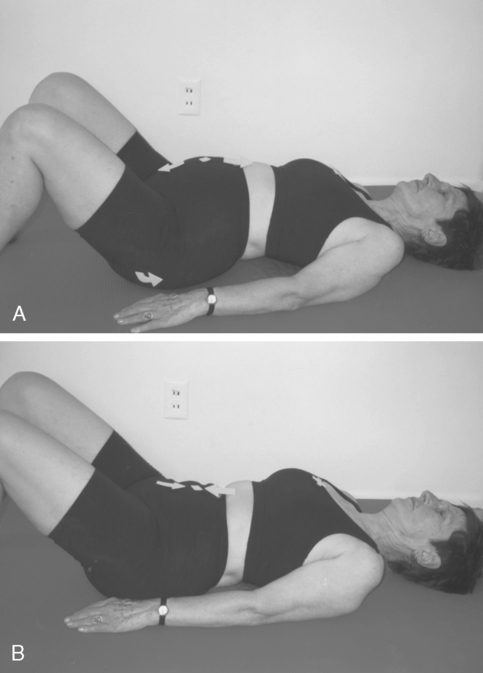

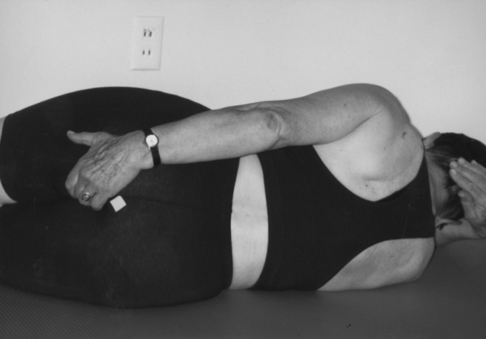

In the side-lying position, the client can place a hand over the gluteal muscles while touching the anal sphincter with a fingertip (Figure 29-7). The client can then try to pucker the anal sphincter, similar to puckering the mouth. The contraction can be faint but is correct if the gluteal muscles remain relaxed. Tightening of the levator ani can be palpated at the perineum, between anus and vagina, or at the side of the tip of the coccyx. It can also be palpated deep in the groin and often can be distinguished from a contraction of the transverse abdominis. Clients learn that contraction of these muscles must precede any contraction of the surrounding pelvic floor muscles, such as the gluteal, adductor, and abdominal and back muscles. In the same position the client can also feel how a cough moves the pelvic floor muscles in a caudal direction. During proper breathing a gentle, rhythmical downward movement occurs during inhalation (eccentric for the pelvic floor and concentric for the pulmonary diaphragm). The client then tries to tighten the pelvic floor muscles before coughing and feels less caudal movement of the pelvic floor muscles.119,120 Sensory awareness of relaxation of the pelvic floor muscles may require education, visualization, and tactile feedback. It may be very difficult to learn to relax muscles that have been tight for a long time.

Feeling the pelvic floor.

Feeling the pelvic floor.Coordination of breathing with pelvic floor muscle activity

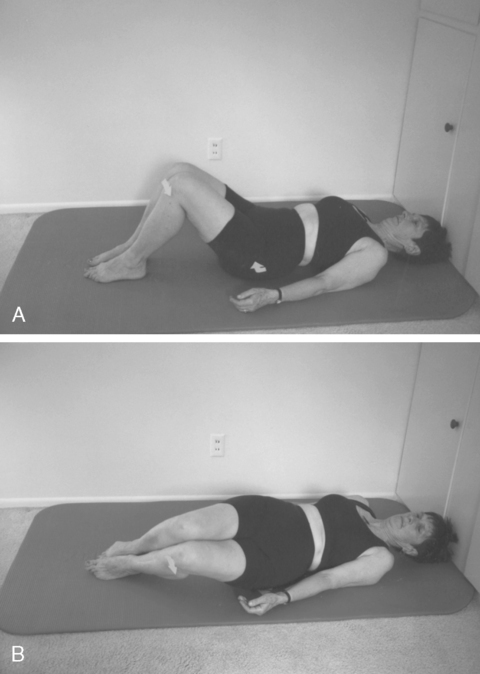

The client learns to contract the pelvic floor muscles while exhaling (eccentric activity for the pulmonary diaphragm, concentric activity for the pelvic floor muscles) and relax those muscles while inhaling. This can be done in different positions, such as supine, side lying, on all fours, sitting, or standing. When coughing, sneezing, lifting, and changing positions, such as from supine to side lying, the pelvic floor contraction must precede the activity (Figure 29-8). In contracting the pelvic floor before saying an explosive word such as a forceful “kick,” then relaxing the pelvic floor by slowly saying “aaaaand,” before tightening once more before saying “kick” again, the sequence of contraction and relaxation is learned.119,120

Strengthening exercises

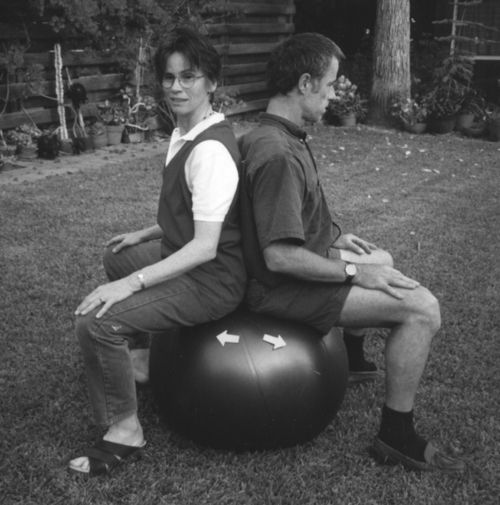

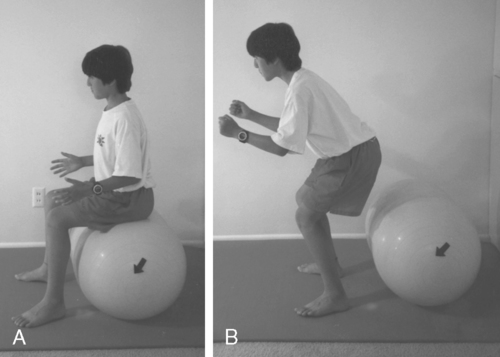

Strengthening exercises of the pelvic floor muscles must include fast-twitch muscle fiber training with quick fast-twitch muscle contraction, which can be done by bouncing on the ball as demonstrated in Figure 29-9.

A, Training fast fibers by bouncing on a double ball. B, Tightening the pelvic floor while lifting up.

A, Training fast fibers by bouncing on a double ball. B, Tightening the pelvic floor while lifting up.Slow-twitch muscle fiber training requires holding the contraction at the end for 5 to 10 seconds. This is demonstrated in Figure 29-10; the client tightens the pelvic floor, gives herself resistance in a diagonal direction, and holds the contraction of the pelvic floor muscles for 5 to 10 seconds. The right ischial tuberosity initiates the movement toward the left knee, which should not move in space, as indicated by the X. The chest also is a “fixed” point marked by an X. All movement comes from the pelvis.

Training of the slow muscle fibers by holding the contraction for 5 to 10 seconds at the end of the movement.

Training of the slow muscle fibers by holding the contraction for 5 to 10 seconds at the end of the movement.Because the pelvic floor muscle fibers run in a sagittal and frontal plane as well as in a diagonal direction, movements in different directions should be included to maximize the benefit of strengthening exercises. The Swiss ball allows movement in all directions as a functional activity. When two persons sit back to back on a ball (Figure 29-11), one person can pull the ischium in the direction of the knees, which do not move, while the other person tries to slow down the movement. This requires eccentric activity of the pelvic floor muscles. Isometric muscle activity occurs when both pull at the same time with the same force. In Figure 29-12, two 12-year-old children tighten their pelvic floor muscles during exhalation while pulling the ball with the feet. Many exercises with or without the ball can be adapted with the Heller and Tanzberger concepts.92,95,97,119,120 Muscle strengthening is not done in isolation but is trained during functional movement activities such as lifting a grocery bag or hitting a tennis ball.

Programming of functional activities

Pelvic floor muscle activities must be tied to a function, such as getting up from a chair and tightening the pelvic floor muscles during exhalation (Figure 29-13). The exercises must be repeated many times in different combinations until they become automatic. The process of acquiring these skills is part of procedural learning.7,8,124–128 The client must be empowered to make changes in lifestyle activity and be motivated to achieve the changes. Only then will the client be willing to exercise for months until the task becomes automatic.8,9,124–128 To improve motor control of a task, the exercises selected must be meaningful and varied as well as challenging. Mental practice, visualization, part-to-whole task practice, prepractice instructions, appropriate feedback, and guidance are all part of motor learning and are incorporated in the Heller and Tanzberger approaches.124–128

Precautions

For clients who do not feel safe on a ball, a double ball, a ball base, or a flat ball that fits onto a chair (Figures 29-14 and 29-15) can be used. All are commercially available. Exercises also can be performed between two chairs or in a corner so that the ball cannot roll away. When learning the exercise, a belt can be used at first to hold onto a client. The ball should not be used if a severe cognitive deficit in the client makes the activity unsafe. Any medical condition that endangers a client on a ball makes these exercises contraindicated and requires a change of exercise and equipment.119,120,129 Many possibilities for functional exercises exist that are based on motor learning and motor control principles as described by Umphred.108 The client can walk or perform favorite gym exercises by incorporating pelvic floor strengthening and breathing coordination after learning how to do the exercises correctly. Functional training can also be achieved by incorporating the pelvic floor activity into certain movements that are done every day, such as lifting a child or grocery bag, getting up from a chair or out of a car, or turning in bed.

Flat ball (sit fit).

Flat ball (sit fit).In addition, therapists must be aware of the involvement of other systems, such as the autonomic system or the limbic system. The patient may be nervous or fearful, depressed, and sleep deprived or may have pain in addition to the incontinence problem.108,130 Some clients may have been abused, which may be manifested in multisystem involvement.91 An environment of trust, understanding, and sensitivity toward the client’s problems must be created.

Case studies

None of the four clients discussed in this chapter underwent biofeedback or electrical stimulation for treatment, and most of the clients had performed Kegel exercises without success. In clients who are unable to learn to feel their pelvic floor muscles, electrical stimulation or biofeedback may be helpful. Functional activities, including proper breathing, should be performed during biofeedback. Isolated contractions of the pelvic floor muscles by using a device without incorporating functional activities does not seem to restore the many different functions of the pelvic floor. Therefore the use of cones without proper pelvic floor muscle training remains questionable. All the clients mentioned in the case studies were extremely motivated, which is not uncommon in patients who have pelvic dysfunctions. They are more than willing to follow their regimen. Problems arise when the client is cognitively impaired or when an illness affects motivation (Case Studies 29-3 and 29-4).

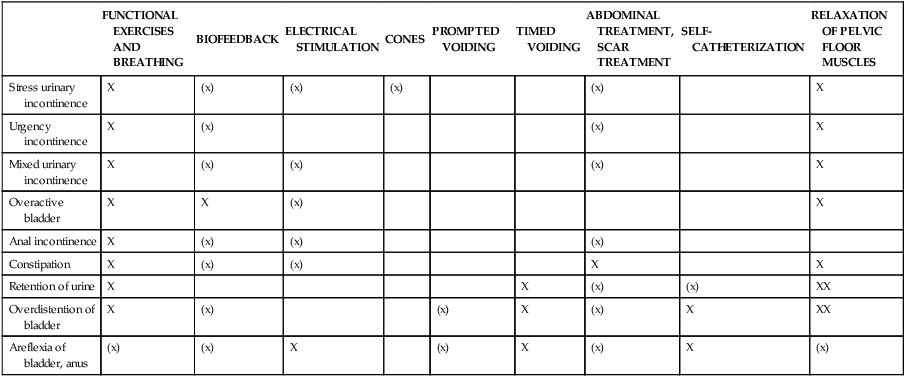

Treatment options for pelvic floor dysfunction

Cognitively impaired clients

Adjustments must be made and functional barriers decreased to help cognitively impaired clients maintain or achieve continence (Table 29-1). Prompted voiding, timed voiding,16,131–133 and medicine can be used when a client has cognitive problems and cannot go to the bathroom independently. In prompted voiding, clients (e.g., with Alzheimer disease) are asked at regular intervals whether they have to go to the bathroom. In timed voiding, a client is placed on a commode or toilet at regular intervals. Many clients who are cognitively impaired probably would not be incontinent if they could reach a bathroom and if help were available to unbutton or unzip clothes, open a door, or assist in other aspects of toileting. Timely assistance could prevent falls (and therefore fractures) and incontinence episodes.134

TABLE 29-1

POSSIBLE COMBINATIONS OF TREATMENT OPTIONS FOR BLADDER AND ANAL DYSFUNCTIONS

| FUNCTIONAL EXERCISES AND BREATHING | BIOFEEDBACK | ELECTRICAL STIMULATION | CONES | PROMPTED VOIDING | TIMED VOIDING | ABDOMINAL TREATMENT, SCAR TREATMENT | SELF- CATHETERIZATION | RELAXATION OF PELVIC FLOOR MUSCLES | |

| Stress urinary incontinence | X | (x) | (x) | (x) | (x) | X | |||

| Urgency incontinence | X | (x) | (x) | X | |||||

| Mixed urinary incontinence | X | (x) | (x) | (x) | X | ||||

| Overactive bladder | X | X | (x) | X | |||||

| Anal incontinence | X | (x) | (x) | (x) | |||||

| Constipation | X | (x) | (x) | X | X | ||||

| Retention of urine | X | X | (x) | (x) | XX | ||||

| Overdistention of bladder | X | (x) | (x) | X | (x) | X | XX | ||

| Areflexia of bladder, anus | (x) | (x) | X | (x) | X | (x) | X | (x) |

Clients with a cerebrovascular accident, multiple sclerosis, or parkinson disease

Clients who have neurological deficits are usually not asked whether they have a urinary dysfunction. Not all clients with such diseases are incontinent; some had incontinence before the onset of the neurological disease. OAB syndrome and UUI are common in CVA,35 MS, and other neurological diseases, whereas detrusor-sphincter dyssynergy is common in MS and SCI.30,33 Patients with Parkinson disease can also have nocturia and retention. No matter what the cause, improvement can often be achieved by identifying the dysfunction, explaining the anatomy and physiology to the client, and then offering treatment options. Coordination of diaphragmatic breathing with pelvic floor muscle activity can improve self-control to relax the pelvic floor and improve oxygen supply to the pelvic region. Improving the posture and sensory awareness training can also be integrated to varying degrees. The therapist can help the client improve afferent sensory input and use visualization to learn to contract and relax the muscles properly. A client with retention can learn to emphasize relaxation of the pelvic floor muscles during urination through breathing, proper seating on the toilet, and self-relaxation. Double voiding technique encourages the patient with an overextended bladder to time voiding to every 2 to 4 hours during the day. The patient then attempts to empty the bladder by staying on the toilet longer and trying to void more than once with each trip to the toilet, with supportive cues and timed voiding when the patient has cognitive impairment.34,131,133 Often, functional barriers can be eliminated or help can be provided. With clients who also need strengthening exercises for the pelvic floor and have difficulty sitting on a ball, a flat ball can be used in a chair, or exercises can be adapted to the client’s ability without any devices.

Overdistended bladder

Whether or not the overdistended bladder is neurogenic, the client must learn to time herself or himself to void at regular intervals. In other cases the client may learn to do clean intermittent catheterization and carefully monitor the output of urine. The residual urine in the bladder should be low, approximately 50 mL; measurements consistently higher require further evaluation by a urologist.47 Proper relaxation of the pelvic floor is important; men often can relax the pelvic floor better when urinating in a seated position. Abdominal breathing and coordination with pelvic floor muscle activity are important for these clients and should be restored if a problem is present.

Areflexia

Education is always the most important part of intervention and is done at the beginning. Many clients may need to learn clean intermittent catheterization and timed intervals. In some clients electrical stimulation or biofeedback may help restore some function of the pelvic floor activity; exercise may improve the strength of the pelvic floor muscles once some function returns. Obviously, all therapeutic interventions depend on the extent of the lesion, but as described in Case Study 29-3, discussion with the client regarding the exploration of treatment options is important. This client probably could have been spared wearing diapers for the previous 10 years. She also could have been condemned to wearing diapers for the rest of her life without intervention. All that was needed in her case was to ask about the problem and instruct her in achieving continence.

Anal incontinence

The inability to hold gas or leaking stool can occur in neurogenic and nonneurogenic disorders. Clients who have had resections of the colon may have anal urgency incontinence. They must learn to evaluate what they ate, when the urgency is appropriate, and when a signal is false. They often cannot distinguish gas, liquid stool, and solid stool. A client, after instruction and explanation of the defecation process, stated, “I got it; it is mind over matter.” He was also instructed to use deep abdominal breathing and quick flicks (activation of the fast fibers) and distraction to control the urgency. This helped him to stop and to control the need or motor program that could be identified as running to the bathroom every 30 minutes. He was asked to throw that program out consciously and replace it with breathing and reevaluation of each urgency, which enabled him in a short time to regain control, sleep through the night, and increase the intervals during the day. As with all clients with pelvic floor dysfunction, careful evaluation and education must be completed before beginning the treatment. In the presence of constipation, a careful abdominal evaluation and possible treatment of the viscera,135 such as with colon massage,121 may be indicated because constipation can also be present in clients who leak stool. The client needs to be educated about eating properly. Individuals who eat too much fiber need to drink large volumes of fluid to keep the stool soft. A client with a brain stem injury, for example, had bowel movements only every 5 days. When the family changed the breakfast to fruit and only minimal fiber, the client had daily regular bowel movements.

Summary

Every client with UI, whether male or female, requires a thorough examination. To give the best possible chance for recovery, exercises must be custom tailored and modalities used with discretion. Electrical stimulation and biofeedback cannot replace functional exercises. Modalities may be helpful at the beginning of the treatment if the client has no sensory awareness of the pelvic floor but should be used in combination with exercises. Treatment of the viscera by a knowledgeable therapist should be considered in some clients to achieve full rehabilitation of the pelvic floor dysfunction.135