CHAPTER 10 Pelvic Emergencies

Many diseases that affect the abdomen may also extend to involve the pelvis. These are described in Chapter 9. In addition, trauma does not respect anatomic boundaries, and pelvic injuries following trauma are described in Chapter 3. This chapter covers conditions that are for the most part confined to the pelvis, and a great number of them are related to the genitourinary tract. Although there is some overlap, many of these disease entities are gender specific. In the male, these primarily consist of diseases of the testes and prostate and include testicular torsion, orchitis, epididymitis, maldescended testis, and prostatitis. In the female the entities primarily affect the ovaries and uterus and include ovarian cysts, endometriosis, ovarian torsion, tubo-ovarian abscess, and ectopic pregnancy. The most frequent presentation in the male is testicular pain and in the female either pelvic pain or dysfunctional uterine bleeding. The imaging modalities used to investigate these entities include sonography, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); however, in the emergency room setting, sonography is the first-line modality of choice for many of these pelvic pathologies.

MALE DISORDERS

Testicular Torsion

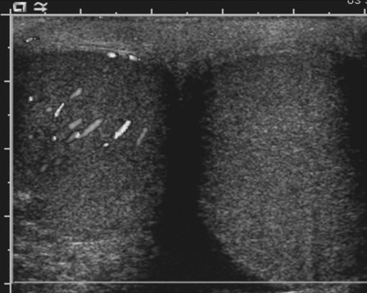

Sonography is the preferred imaging examination for the diagnosis of testicular torsion because of its high sensitivity and specificity. Gray-scale ultrasound findings are often completely normal when torsion is present, and the testes may appear symmetric with respect to both size and echogenicity. A small hydrocele may be present on the affected side. Within a few hours of the onset of symptoms, the scrotal wall will appear thickened, and the testis and epididymis will appear enlarged and hypoechoic secondary to inflammation and/or hemorrhage. Color Doppler is crucial for the diagnosis of torsion. The lack of demonstrable blood flow to the affected testis, assuming appropriate ultrasound settings are used, is virtually pathognomonic for torsion (Fig. 10-1). In prepubertal patients it is often difficult to demonstrate the presence of blood flow even in normal testes. Two potential false negative scenarios need to be considered when evaluating for torsion. First, a torsed testis may untwist spontaneously with resultant hyperemia on color Doppler, thus mistaking testicular torsion for epididymo-orchitis; and second, incomplete torsion may result in venous occlusion without arterial occlusion, which may result in arterial flow being detected in the testis despite torsion being present.

Torsion of the Testicular Appendages

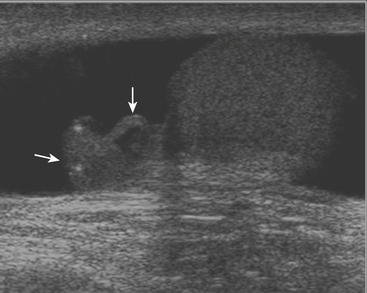

While there are four testicular appendages, only two are commonly visible at ultrasound: the appendix testis and appendix epididymis. These appendages are remnants of embryonic ducts and serve no real function. Because they are attached by a small pedicle, they are prone to torsion. Torsion of these appendages is one of the most common causes of acute scrotal pain in children. The appendix testis is more commonly affected than the appendix epididymis, although it is often difficult to identify the offending appendage. Patients are usually young, prepubertal males who complain of acute onset scrotal pain. On clinical examination there may be a bluish discoloration of the skin at the site of pain, which is called the “blue dot” sign and is pathognomonic. At ultrasound the torsed appendix is often identified as a round, extratesticular, extra-epididymal mass lacking color Doppler flow (Fig. 10-2). A reactive hydrocele may be present, as well as scrotal wall skin thickening.

Epididymitis and Orchitis

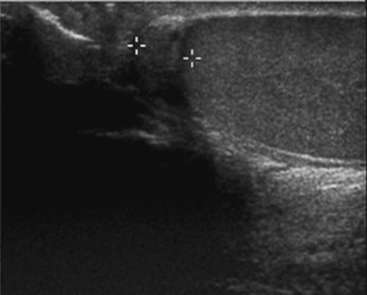

Ultrasound examination of a patient with epididymitis demonstrates enlargement of the epididymis, primarily the head, with heterogeneous echotexture. On color Doppler evaluation there is increased blood flow to the epididymis and/or testis (Fig. 10-3). A reactive hydrocele may be an associated finding. When the entire testis is involved, it is often enlarged and has altered echogenicity. On gray-scale imaging findings alone, the appearance of the testis may mimic a diffusely infiltrative disease such as leukemia or lymphoma, although the clinical presentation should suggest the correct diagnosis. Untreated epididymo-orchitis may progress to scrotal abscess formation or may result in testicular infarction, which may lead to testicular atrophy. In patients with epididymo-orchitis, a follow-up sonogram performed 4 to 6 weeks following the initial event is advised in all cases to ensure complete resolution of the imaging findings following appropriate interval therapy. This is important in order to exclude an underlying tumor as the cause for the patient’s symptoms. It is uncommon for a testicular tumor to present with acute scrotal pain; the accepted figure is less than 10% of tumors. It may occur and is usually due to acute hemorrhage or infarction of the testis that contains the tumor. Orchitis secondary to infection with mumps occurs in approximately 25% of patients that contract the disease. The sonographic findings include an enlarged hypoechoic testis, a small hydrocele, and sometimes thickening of the scrotal wall. Infertility may occasionally result following mumps orchitis. Severe scrotal infection may result in the rare condition called Fournier gangrene. This is a fulminant infectious process involving the scrotal wall and skin of the perineum that is in essence a fasciitis. The severe infection may result in gas formation along the fascial planes of the scrotal wall. Sonographic findings include the findings of epididymo-orchitis along with small echogenic ill-defined foci within the scrotal wall. These foci represent gas, and this finding requires urgent communication to the referring physician as surgical débridement may be required. In questionable cases, CT may be performed, which will clearly show the presence of any gas as hypoattenuating foci within the scrotal wall (Fig. 10-4).

Cryptorchidism

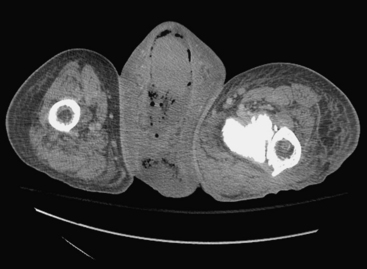

The arrest in the descent of the testis along its normal path is one of the most common disorders of the genitourinary tract. It occurs in up to 3% of term infants, although the majority of these will descend naturally over the first few months of life. Nearly four out of five maldescended testes in adults are located at or below the level of the inguinal canal. Although maldescended testes are associated with a host of congenital syndromes, this is not always the case and the condition may occur in isolation. The most damaging consequence of maldescended testes is infertility; infertility rates in unilateral maldescent are reported to be close to 20%, but this rises to 75% in cases where the maldescent is bilateral. There is a high rate of germ cell tumors in maldescended testes, and this risk extends to the contralateral descended testis as well. Maldescended testes are also at increased risk of both torsion and trauma and hence should be considered in any patient presenting with pelvic or scrotal pain in which both testes are not clearly palpable. Since the majority of maldescended testes are found in the inguinal canal, the testis may usually be identified by sonography. Maldescended testes appear as small, usually hypoechoic, rounded or oval structures along the line of the inguinal canal (Fig. 10-5). Care should be taken not to confuse the small testis with a lymph node. Any focal areas of heterogeneity within the testis could represent malignant degeneration. The sensitivity of sonography for detecting maldescended testis varies between 75% and 97% and depends on whether the testis is palpable or not. Once the maldescended testis lies higher than the inguinal canal, it becomes difficult for sonography to locate it. Other imaging modalities that may be used to locate the testis include CT and MR. With multidetector CT, the small soft tissue mass of the maldescended testis is usually identifiable, a situation that was not always the case in the era of large slice thickness CT. T2-weighted MR imaging may be useful to locate the high signal testis, which may be best identified using coronal plane imaging along the plane of the gonadal vessels.

Prostatitis

Acute prostatitis is, in essence, a clinical diagnosis, and imaging is rarely required to make the diagnosis. It is most commonly caused by recent instrumentation or surgery; however, infection may also spread from the urinary tract. Untreated or inadequately treated prostatitis may lead to prostate abscess formation. Performing transrectal sonography in patients with acute prostatitis may help to make the diagnosis even before imaging, as the passage of the probe may be exquisitely painful. The sonographic appearance of acute prostatitis is primarily of a heterogeneous prostate gland that may show focal areas of hypoechogenicity with demonstrable increased vascularity usually within the peripheral zone. In severe cases, the hypoechogenicity may be more diffuse and the increased vascularity may be seen throughout the gland. Chronic prostatitis usually appears as bands of increased echogenicity representing areas of fibrosis. There is usually little evidence of increased vascularity. Prostatic abscess appears as a well-defined walled collection that contains hypoechoic fluid (Fig. 10-6). The fluid is usually somewhat complex with foci of increased echogenicity within it as well. Gas present in the abscess is seen as irregular foci of increased echogenicity with so-called “dirty” shadowing behind it.

FEMALE DISORDERS

Hemorrhagic Ovarian Cyst

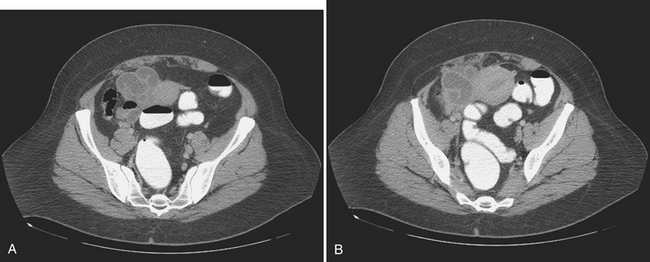

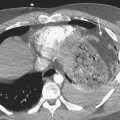

Physiologic ovarian follicles measure less than 3.0 cm in diameter. Most hemorrhagic cysts measure 3.0 to 3.5 cm in diameter, have a thin outer wall, and demonstrate posterior acoustic through-transmission. Fine, reticular septations resembling a fishnet pattern are a common finding at ultrasound. These septations represent fibrin strands, which contain no blood flow. In some patients the hemorrhagic cyst contains retracting clot. While a large portion of the cyst appears anechoic, the retracting clot appears as an adherent, echogenic structure within the cyst that contains no blood flow. In rare cases, when the clot becomes very small it can simulate a mural nodule and raise concern for ovarian neoplasm. Fluid–fluid or fluid–debris levels can also be demonstrated within a hemorrhagic cyst. Hemorrhagic cysts can be complicated by rupture, with free spill of hemorrhagic contents into the pelvis. When this occurs, echogenic fluid will be demonstrated within the pelvis surrounding the uterus and adnexa. In some cases, the hemoperitoneum may be massive. Although the sonographic features are well described, given that many patients with a ruptured hemorrhagic cyst present with pelvic pain, in the emergency room setting this is often interpreted as abdominal pain, and CT imaging may be the first modality used. We are seeing CT imaging of ovarian cysts, hemorrhagic cysts (Fig. 10-7), and ruptured cysts (Fig. 10-8) with increasing frequency. The normal ovaries may be difficult to identify on CT imaging, and identification often depends on hormonal status. When the ovaries are larger, as in younger women of childbearing age, they are more likely to be identified. Similarly, in patients with little pelvic fat, the ovaries may be difficult to distinguish from loops of unopacified bowel in the pelvis. Often the position of the ovaries is assumed and the usual location is either side of the uterus along the margin of the round ligament. In young patients with malignancy that requires pelvic radiation therapy, the ovaries are frequently surgically sutured to the superolateral aspect of the pelvic wall. This is done to move the ovaries out of the path of the treating radiotherapy beam. In these cases, the ovaries appear as solid masses with cystic components located superiorly and laterally to their usual position. These masses should not be mistaken for pathology, particularly tumor, and knowledge of the prior pexy procedure is useful to avoid confusion. The findings of a simple ovarian cyst are similar to those of a cyst elsewhere, namely, a well-defined round or oval mass in the location of the ovary with an imperceptible wall and containing simple fluid with Hounsfield unit (HU) values of 10 or less. A hemorrhagic cyst might be identified as a mass similar to a simple cyst, but there may be an irregular enhancing ring seen within the cyst, which represents the enhancing involuting wall of the cyst. The CT findings of a ruptured cyst are more variable. Often the cyst itself can no longer be identified because the contents have spilled into the peritoneal cavity. What may be seen is free fluid in the cul-de-sac or even in the location of one of the adnexa. This fluid is frequently of slightly higher attenuation than simple fluid and may have an HU value of 60 to 80. This represents the blood from the ruptured cyst. Active extravasation may occasionally be seen as a line of high density representing administered intravenous contrast being lost into the peritoneal cavity.

Ovarian Torsion

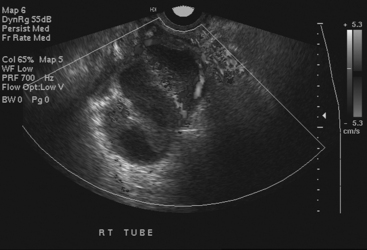

Pelvic ultrasound is the study of choice for evaluation of ovarian torsion. Normal ovaries often appear hypoechoic relative to the adjacent pelvic tissue and have an ovoid or ellipsoid shape. Microcystic follicles are routinely identified in normal ovaries. When the ovaries demonstrate normal gray-scale imaging characteristics and have a normal size and shape, color Doppler evaluation is usually not necessary. If, however, one ovary appears abnormally large relative to the other side, torsion may be present. In nearly all cases of ovarian torsion, the affected ovary is massively enlarged and has a round or globular configuration. In neonates and young girls ovarian torsion is commonly seen as a large cystic mass with fluid–debris levels. In young or adolescent girls the more classic imaging appearance is an enlarged, echogenic ovary with multiple enlarged peripheral follicles. In other cases, the ovary may appear as a complex cystic mass secondary to the presence of an underlying cyst or tumor (Fig. 10-9). Color Doppler evaluation of the ovary often reveals an absence of blood flow, a finding classically associated with ovarian torsion. However, torsion may be present even if arterial waveforms are demonstrated because the ovary has a dual blood supply (from both the uterine and ovarian arteries). The presence of arterial waveforms within the ovary should not sway the diagnosis away from ovarian torsion if the gray-scale imaging findings and physical examination are consistent with torsion.

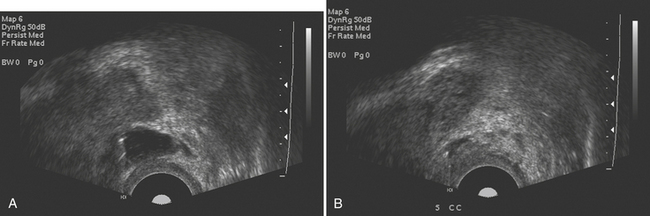

Disorders of the Fallopian Tubes

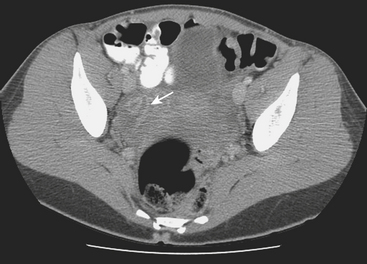

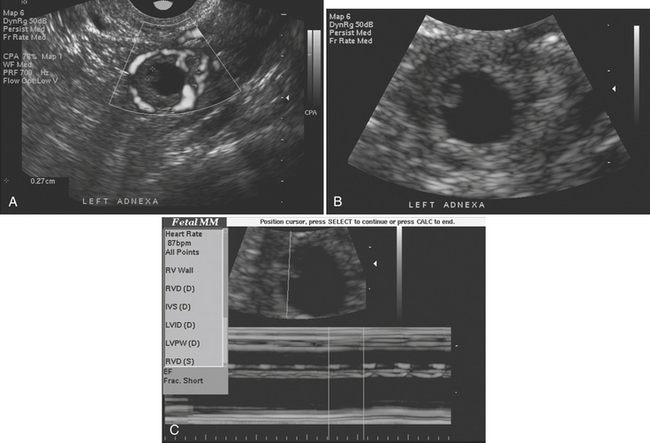

Disorders of the Fallopian tubes include hydrosalpinx, pyosalpinx, and tubo-ovarian abscess. Hydrosalpinx is seldom an acute condition and is most frequently an incidental finding. It results from occlusion of the Fallopian tube and is often bilateral. The most common etiology, infection, often follows instrumentation. The obstruction leads to dilatation of the Fallopian tube, which becomes filled with serous fluid. Although hydrosalpinx can present with acute pelvic pain, the condition may remain asymptomatic; however, long-term consequences include infertility. Sonographic findings are usually characteristic, and a dilated tubular cystic structure with anechoic fluid within is usually found. When a hydrosalpinx becomes secondarily infected the condition is known as pyosalpinx. This presents as acute pelvic pain with the signs and symptoms of acute infection including elevated fever and white cell count. The fluid within the Fallopian tube will no longer be anechoic on sonography, indicating the presence of pus within the tube (Fig. 10-10). Aggressive antibiotic therapy is indicated, but when the tube is extremely distended, percutaneous or transvaginal drainage may be required. A condition that overlaps pyosalpinx and one that occurs more frequently is tubo-ovarian abscess formation. This in essence has a similar etiology to pyosalpinx in that the most common cause is a sexually transmitted disease. The infection travels along the Fallopian tube and results in an abscess forming in the adnexa. The clinical presentation usually leads to the diagnosis being suspected. Sonography is again the imaging modality of choice. A complex mass may be identified in the adnexa, and the mass may be shown to lie outside of the ovary. On transvaginal sonography, gentle pressure placed directly over this mass will be exquisitely painful. This may help to confirm the diagnosis, as other causes of complex adnexal masses tend not to cause such discomfort. As with other pelvic pathologies, the presentation may be interpreted as abdominal pain, rather than pelvic pain, and CT may be the first-line imaging modality used. In this case, a tubo-ovarian abscess may be seen as a pelvic abscess with thick walls and may contain fluid and/or solid components (Fig. 10-11). The presence of a dilated tubular structure on the ipsilateral side representing a hydro- or pyosalpinx may help to distinguish this abscess as a TOA rather than an appendiceal or diverticular abscess.

Ectopic Pregnancy

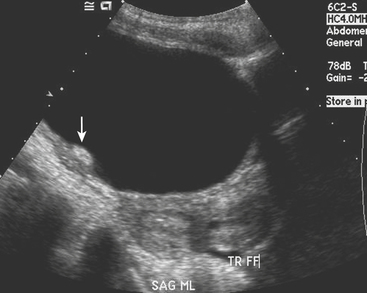

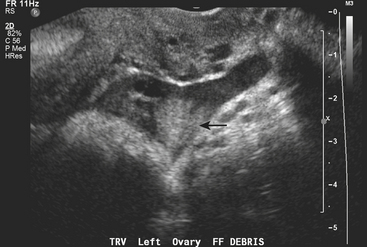

Ectopic pregnancy is a common condition that may result in death if not adequately diagnosed and treated; as such, missing the diagnosis is a far greater sin than making a false positive diagnosis. Ectopic pregnancy is responsible for up to 15% of maternal deaths. By definition, any female patient with a positive pregnancy test and an empty uterus should be regarded as having an ectopic pregnancy until otherwise proven. It is not always possible to identify the ectopic pregnancy directly, and not identifying this should never be taken as evidence that the patient does not have an ectopic pregnancy. Ectopic pregnancy usually presents with pelvic pain and may well be associated with bleeding. On imaging, the best way to determine that an ectopic pregnancy is not present is to identify an appropriately positioned gestational sac. In cases with ectopic pregnancy, the sloughing of the decidua may result in the appearance of a pseudogestational sac. This can be differentiated from a gestational sac as a fluid collection within the endometrial canal surrounded by a single decidual layer, unlike the gestational sac, which appears as a fluid collection within the decidua that abuts the endometrium or as concentric rings, the so-called “double decidual” sign. The most specific sonographic sign confirming ectopic pregnancy is the identification of a live embryo that lies outside the uterus, usually in the adnexa (Fig. 10-12). This sign is positively identified in only approximately 20% to 25% of cases of ectopic pregnancy and therefore cannot be relied on to make the diagnosis. A nonspecific complex adnexal mass in a patient with a positive pregnancy test is strong evidence to support the presence of an ectopic pregnancy. Complex free fluid in the pelvis is also a good indicator in the correct clinical setting (Fig. 10-13). The presence of an adnexal mass in association with complex free fluid has a sensitivity of close to 40% but a specificity of 99% for the detection of an ectopic pregnancy. It is important to remember that up to one third of patients with an ectopic pregnancy may have a completely normal sonogram. Hence the importance of the mantra “positive pregnancy test with an empty uterus equals ectopic pregnancy until proven otherwise.”

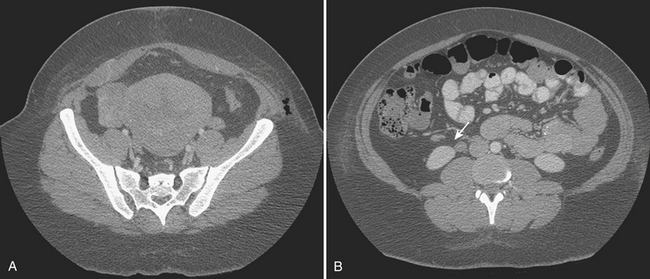

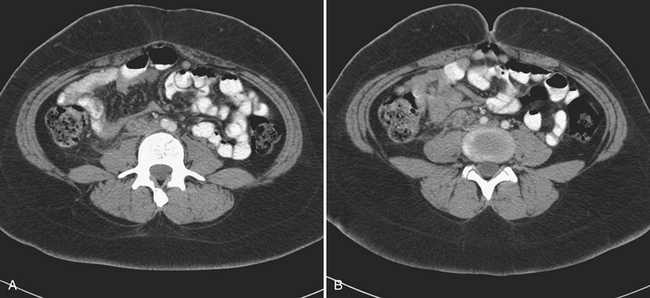

Ovarian Vein Thrombosis

The diagnosis of ovarian vein thrombosis by sonography is often limited by the presence of overlying bowel gas. The characteristic finding is that of a tubular hypoechoic structure extending from the adnexa cranially. No blood flow may be identified within this structure when interrogated with color Doppler. There may be associated enlargement of the ovary on the affected side, although frequently it is difficult to be certain of this. It may be difficult to definitively discern ovarian vein thrombosis from hydronephrosis or thrombosis of the inferior mesenteric vein. CT is the most likely imaging modality to be used in the emergency room, particularly if the patient presents with fever and abdominal pain. Appendicitis is frequently the suspected diagnosis. The CT findings that make the diagnosis are the identification of an enlarged ovarian vein that contains either occlusive or nonocclusive thrombus (Fig. 10-14). This may be identified as a focus of hypoattenuation within the enhancing vein or as an abruptly occluded vessel that is dilated distally. There is usually some nonspecific stranding of the fat adjacent to the vessel resulting from the thrombosis. This may be exuberant if there is superimposed infection resulting in septic thrombophlebitis (Fig. 10-15).