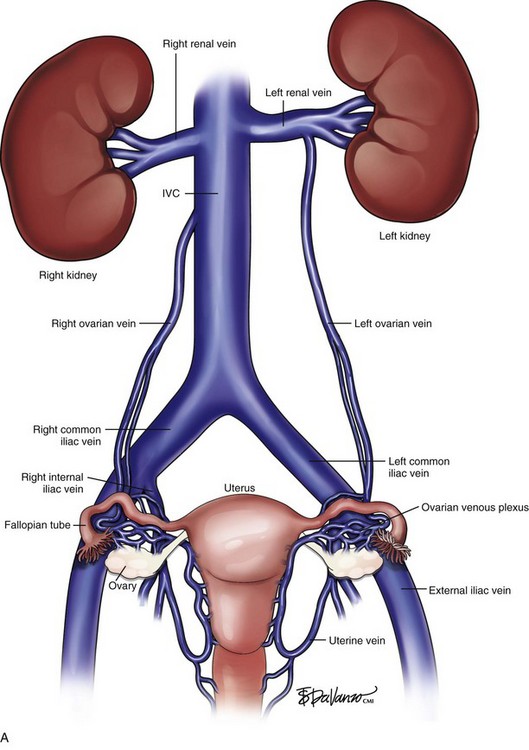

Chapter 17 Pelvic Congestion Syndrome and Ovarian Vein Reflux

Background

Pelvic congestion syndrome (PCS) is an underdiagnosed condition causing chronic pelvic pain. PCS was first described by Taylor in 1948,1 who described a number of specific patients suffering with pelvic pain; these patients had pelvic and ovarian varicosities from ovarian vein incompetence. Women with PCS are usually of menstruating age who report pelvic heaviness and pain that is aggravated by standing. They are typically multiparous and report that their symptoms worsen during the premenstrual period. These patients may also complain of dyspareunia.

Classification

As with many conditions there is a spectrum of pelvic venous syndromes that may affect patients. Scultetus et al.2 classified these patients into four types. Type 1 includes patients with limited vulvar varices. Patients with hypogastric vein reflux (including internal pudendal and obturator branches), usually with vulvar varicosities and hemorrhoids, represent type 2. Type 3 patients are diagnosed with gonadal vein obstruction due to a mesenteric aortic compression of the left renal vein (nutcracker syndrome). Type 4 patients have gonadal vein insufficiency that is characteristic of PCS. These patients may have lower extremity varicosities that originate in the pelvis and may also have associated hypogastric vein reflux.

Etiology

The cause of PCS is unknown and poorly understood. However, autopsy studies have found that a percentage of patients may have congenital absence of valves in the left ovarian vein.3 Interestingly, a significant number of patients (40%) with ovarian vein incompetence may remain asymptomatic. Additionally, the development of the incompetence and symptoms may be associated with mechanical stresses such as pregnancy as well as with certain hormonal effects.

Diagnosis

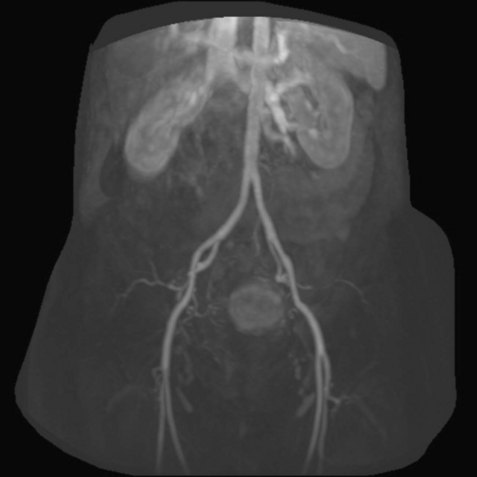

The diagnosis of this condition requires a significant clinical suspicion because there are many disorders that present with pelvic pain. The diagnosis for many years relied on clinical suspicion that would be confirmed at the time of direct venography. Additionally, a number of cases have been diagnosed with the discovery of pelvic varicosities at the time of laparoscopy. The use of transabdominal and transvaginal ultrasound has been described as a manner to diagnose PCS in a patient with pelvic pain4; however, its accuracy in widespread practice is limited. At present, when there is a clinical suspicion, the diagnosis is confirmed with either computed tomography venography (CTV) or magnetic resonance venography (MRV).5,6 MRV is the study of choice because of its lack of ionizing radiation and its ability to perform time-resolved imaging7 (Fig. 17-1).

Treatment

In the early years of the condition, surgical treatment consisted of surgical ligation of the ovarian vein. Recently there have been reports of laparoscopic ligations. Most commonly, percutaneous transcatheter treatment is used. Transcatheter treatment was first reported by Edwards in 1993,8 and these treatments have continued to adapt in technique over the years.

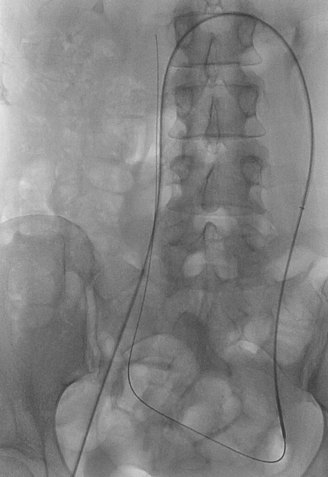

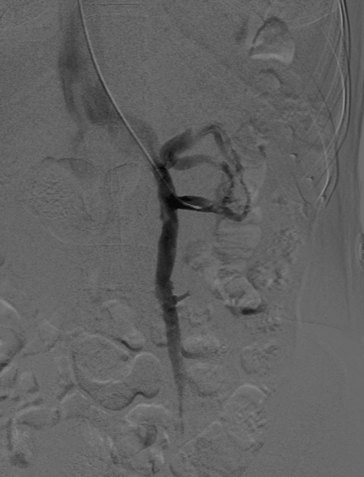

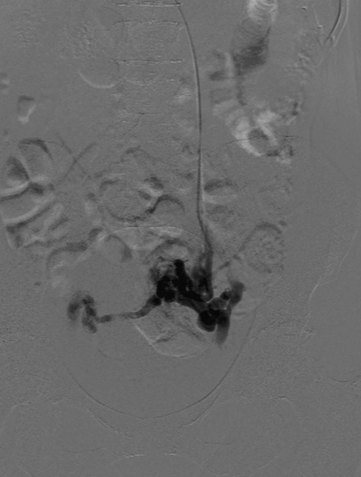

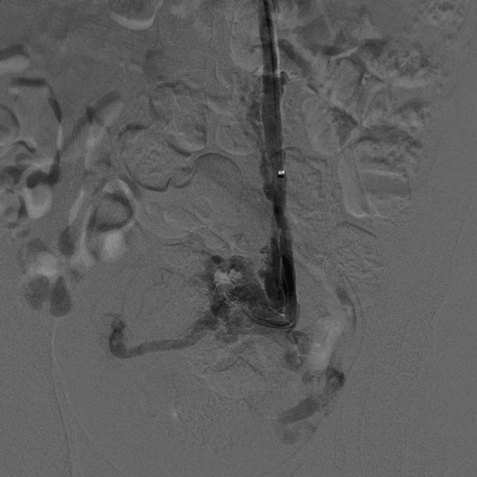

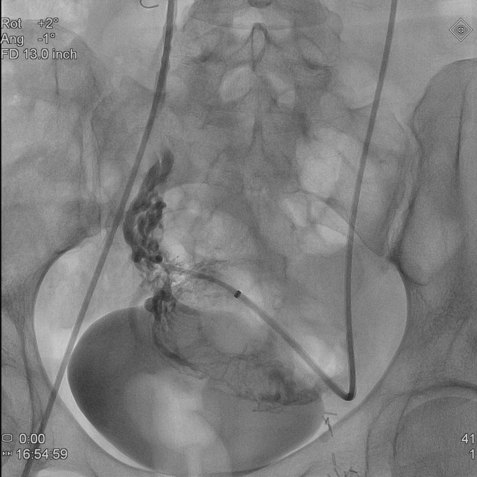

The percutaneous transcatheter treatment can be performed from either the femoral or jugular approach. We prefer the jugular technique as it allows a more natural angle into the left renal vein. Selection of the left as well as the right ovarian vein can be very difficult from the femoral approach because of the acute angle at the origin of the right ovarian vein with the inferior vena cava (Fig. 17-2). Injection of the left renal vein will usually depict the presence of a dilated (6 to 10 mm) left ovarian vein, which is incompetent (Fig. 17-3). There are usually cross pelvic collaterals filling the right ovarian venous system (Fig. 17-4). In a percentage of cases, the reflux causes filling of the internal iliac vein branches. Venography can be done during the Valsalva maneuver if the resting venogram does not demonstrate an enlarged ovarian vein.9 Additionally, the venogram can be repeated in a semierect position if a tilt table is available.

It is important to exclude a compression of the distal left renal vein between the superior mesenteric artery and the aorta (nutcracker syndrome) as the cause of the left ovarian vein enlargement. This condition is diagnosed by an elevated pullback or simultaneously measured renocaval gradient. The gradient in this region should normally be 1 mm Hg or less and is typically greater than 5 mm Hg in patients with nutcracker syndrome.10 This treatment for these patients involves relief of the compression using surgery or stent placement.

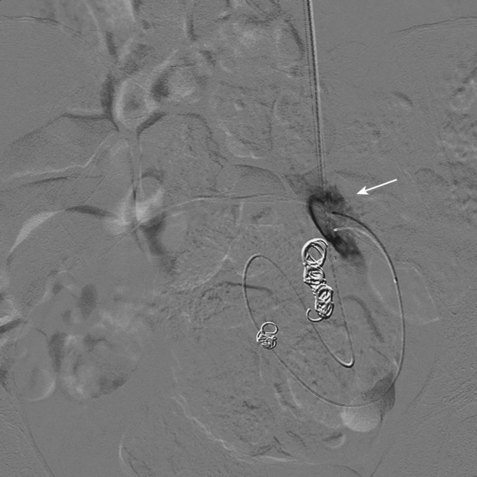

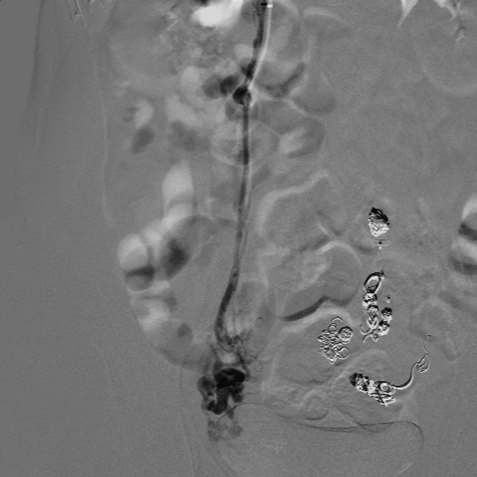

Once that the diagnosis has been established and the decision to treat the patient made, if the ovarian vein is large, a long 6-Fr sheath or guide catheter can be advanced into the vein for the purpose of using occluding devices and catheters in a coaxial fashion (Fig. 17-5). If a sheath or guiding catheter cannot be placed into the ovarian vein, a standard 5-Fr catheter can be used to negotiate the vein. It is important to place the catheter as proximal in the pelvis as possible. It is common to opacify small pelvic collaterals while the vulvovaginal varicosities can rarely be seen filling. We usually treat these small deep pelvic collaterals with the aid of a microcatheter and a combination of coils and liquid embolic agents and sclerosants (Figs. 17-6 and 17-7). However, care needs to be taken on superficial vulvovaginal varicosities. Treatment of the incompetence in the ovarian vein and deep pelvic vessels is usually sufficient to reduce the pressure load on these vessels. When transpelvic collaterals are identified, a microcatheter is used to catheterize these small transpelvic collaterals and gain access to the right ovarian system.

In our practice, we traditionally treat the left ovarian vein and will study and then treat the right ovarian vein (Fig. 17-8). The right ovarian vein is usually more challenging to identify and catheterize. This vein usually arises from an acute angle slightly anterior and inferior to the right renal vein (Fig. 17-9). From the femoral approach, a reverse-curve catheter may be helpful, and from the jugular approach, a multipurpose- or cobra-shaped catheter often is ideal. Previous imaging can be extremely helpful to identify the origin of this vein prior to undertaking a search that may become prolonged. In less common instances, the right ovarian vein may arise farther below the renal vein than anticipated, from the right renal vein directly, or from a common trunk with lumbar veins.11 Therefore, a detailed and methodical evaluation of the inferior vena cava must be conducted if the vein is not immediately obvious. At times in our practice, we have catheterized the left gonadal vein and passed a microcatheter across the transpelvic collaterals and up the right ovarian vein and then treated the patient working retrograde from the origin of the right ovarian vein back across the pelvic veins and up the left ovarian vein.

Traditional treatment involves a combination of sclerotherapy of the small vessels and coil embolization of the ovarian vein and some of the larger collaterals (Fig. 17-10). With the catheters in the vessels below the pelvic brim, sclerosants and liquid embolic agents are used.12 Specifically, sclerotherapeutic agents that are used are “off label” for this indication and include 3% STS (sodium tetradecyl sulfate) foam, 2% polidocanol (Aethoxysklerol), and 5% sodium morrhuate/Gelfoam slurry. Before the injection of any liquid sclerosant or embolic agent, it is advisable to determine the volume of agent needed as well as the rate at which the agent should be injected. This is achieved by testing with small contrast injections to determine how much contrast is needed to fill a group of collaterals and to evaluate the presence of reflux. Once this has been determined, the embolic agent is injected at the same rate. Care must be taken to avoid over-injection and refluxing into the inferior vena cava via collaterals. Other liquid embolic agents that have been used include glue (embucril), Onyx, and Gelfoam slurries. The ovarian vein may have a number of accessory veins requiring the packing of coils at several levels throughout the course of the left ovarian vein. Coils are oversized to prevent venous embolization of the coils.13 Embolization plugs have also been used along with coils (Fig. 17-11).

Controversy exists as to the treatment of associated internal iliac and deep venous collaterals. Some authors will not treat internal iliac vein collaterals during the initial ovarian vein setting. If the symptoms continue, they will readdress these veins by selecting the internal iliac vein branches and embolizing them 3 to 8 weeks after the ovarian vein treatment.14 Usually, if reflux into the internal iliac vein system can be identified at the time of initial venography, we treat these vessels to improve pelvic and lower extremity symptoms. The filling of thigh varicosities from the reflux is usually the cause of patients’ extremity symptoms, especially in patients with no superimposed saphenofemoral incompetence. The size of the vessels may require coil embolization; however, in the proper setting, a controlled injection of sclerosants and liquid embolic agents can be used. In a significant percentage of patients, symptoms will not be relieved unless the internal iliac veins are treated. Again, great care must be taken to avoid reflux into the common iliac vein or inferior vena cava when treating these veins. Complications may include ovarian vein perforation, coil migration, and pain from nontarget sclerosant.

Treatment Effectiveness

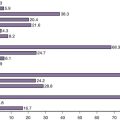

The published literature has demonstrated symptomatic response in more than 80% of patients treated.14,15 In a series of 127 treated patients, there was an 83% improvement in symptoms with a 45-month follow-up (Fig. 17-12). It is common to have to re-treat to improve response, particularly in patients with associated internal iliac and deep pelvic collaterals, which may not be completely treated during the original procedure.

1 Taylor HC. Vascular congestion and hyperemia; their effect on function in the female reproductive organs; clinical aspects of the congestion fibrosis syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1949;57:637-653.

2 Scultetus AH, Villavicencio JL, Gillespie DL, et al. The pelvic venous syndromes: analysis of our experience with 57 patients. J Vasc Surg. 2002;36:881-888.

3 Ganeshan A, Upponi S, Hon LQ, et al. Chronic pelvic pain due to pelvic congestion syndrome: the role of diagnostic and interventional radiology. Cardiovasc Interv Radiol. 2007;30:1105-1111.

4 Park SJ, Lim JW, Ko YT, et al. Diagnosis of pelvic congestion syndrome using transabdominal and transvaginal sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182:683-688.

5 Hiromura T, Nishioka T, Nishioka S, et al. Reflux in the left ovarian vein: analysis of MDCT findings in asymptomatic women. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183:1411-1415.

6 Jin KN, Lee W, Jae HJ, et al. Venous reflux from the pelvis and vulvoperineal region as possible cause of lower extremity varicose veins: diagnosis with computed tomographic and ultrasonographic findings. JCAT. 2009;33:763-769.

7 Pandey T, Shaikh R, Viswamitra S, et al. Use of time resolved magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of pelvic congestion syndrome. J Magn Reson Imag. 2010;32:700-704.

8 Edwards RD, Robertson IR, MacLean AB, et al. Case report: pelvic pain syndrome: successful treatment of a case by ovarian vein embolization. Clin Radiol. 1993;47:429-431.

9 Freedman J, Ganeshan A, Crowe PM. Pelvic congestion syndrome: the role of interventional radiology in the treatment of chronic pelvic pain. Postgrad Med J. 2010;86:704-710.

10 Scultetus AH, Villavicencio L, Gillespie DL. The nutcracker syndrome: its role in the pelvic venous disorders. J Vasc Surg. 2001;34:812-819.

11 Karaosmanoglu D, Karcaaltincaba M, Karcaaltincaba D, et al. MDCT of the ovarian vein: normal anatomy and pathology. AJR Am J Roentgenaol. 2009;192:295-299.

12 Gandini R, Chiocchi M, Konda D, et al. Transcatheter foam sclerotherapy for symptomatic female varicocele with sodium tetradecyl sulfate foam. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2008;31:778-784.

13 Liddle AD, Davies AH. Pelvic congestion syndrome: chronic pelvic pain caused by ovarian and internal iliac varices. Phebology. 2007;22:100-104.

14 Kim HS, Malhorta AD, Rowe PC, et al. Embolotherapy for pelvic congestion syndrome: long-term results. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006;17:289-297.

15 Maleux G, Stocks L, Wilms G, et al. Ovarian vein embolization for the treatment of pelvic congestion syndrome: long term technical and clinical results. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2000;11:859-864.