9 Peeling in Darker Skin Types

Introduction

• The problem being treated

The usual classification of chemical peels comprises superficial, medium and deep peels. For superficial peels, AHA, Jessner’s solution, tretinoin, TCA in concentrations of 10–30% and most recently lipo-hydroxy acid are used to induce an exfoliation of the epidermis. Medium-depth agents such as TCA (30–50%) cause an epidermal to papillary dermal peel with subsequent regeneration. Deep peels using TCA (>50%) or phenol-based formulations penetrate the reticular dermis to induce dermal regeneration. The success of peeling in darker skin is crucially dependent on the physician’s understanding of the chemical and biological processes, as well as of indications, clinical effectiveness and side effects of the procedure (see Box 9.1).

Box 9.1

Key features

• Patient selection

Skin color depends largely on the content and distribution of melanin in the epidermis. The melanocytes of darker skin, in particular black skin, produce more epidermal melanin. In black people, the melanosomes are larger, distributed singly within keratinocytes, and persist up to the stratum corneum. Comparative studies showed some differences between epidermis of black and white people. Although the stratum corneum has an equal thickness in both groups, in black skin there are more cell layers and it has an increased resistance to stripping compared to white skin. Moreover, the stratum corneum of darker skinned people has greater intracellular cohesion, higher lipid content and an increased electrical resistance compared to white skin counterparts. While there is no difference in corneocyte surface area between black and white skin people, desquamation was up to 2.5 times greater in black skin. The epidermis of dark skin is more effective at blocking the transmission of ultraviolet radiation than white skin epidermis due to increased content of epidermal melanin, which confers greater intrinsic photoprotection. An interesting study showed significant differences in the amount of ceramides in the stratum corneum amongst various racial groups. The lowest levels are in black people followed by progressively higher levels seen in white, Hispanic, and Asian people. Darker skin recovered faster after barrier damage induced by tape stripping. Clinically darker skin types are frequently plagued with dyschromias due to the labile responses of cutaneous melanocytes. Main stratum corneum differences between black skin and white skin are depicted in Table 9.1.

Table 9.1 Comparison of stratum corneum characteristics between black skin and white skin

| Characteristic | Black skin | White skin |

|---|---|---|

| Thickness | = | = |

| Number of cell layers | ↑ | ↓ |

| Lipid content | ↑ | ↓ |

| Electrical resistance | ↑ | ↓ |

| Desquamation | ↑ | ↓ |

| Corneocyte surface area | = | = |

| Ceramide content | ↓ | ↑ |

| Resistance to stripping | ↑ | ↓ |

| Recovery from stripping | ↑ | ↓ |

=, equivalent; ↑, higher; ↓, lower

While chemical peeling is an excellent modality to treat photodamage associated skin changes in Fitzpatrick skin types I and III, the main indications for chemical peeling in skin types IV–VI are dyschromias, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH), acne vulgaris, scarring, melasma, and pseudofolliculitis barbae as well as textural changes and oily skin (Box 9.2). Despite major concerns regarding peel complications in darker skin such as PIH, hypopigmentation and scarring, recent studies suggest that peelings, particularly superficial peels, can be performed safely in darker groups.

Overview of Treatment Strategy

• Treatment approach

Chemical peels can be classified by the depth of penetration into the skin (Table 9.2). Superficial peelings (epidermis to upper papillary dermis) are the most commonly used peels in all phototypes. These agents include tretinoin 1–5%, TCA 10–35%, glycolic acid solution 30–50% or glycolic gel 70%, salicylic acid 20–30% in ethanol and Jessner’s solution (Combes’ formula).

| Peel Type | Depth (µm) | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Superficial | 100 | Glycolic acid (buffered); salicylic acid; Jessner’s; TCA 10–15%; Combination peels: TCA + salicylic acid; Jessner’s + salicylic acid; Vi Peel™; Nomelan fenol kh; Melanage™ |

| Medium | 200 | Glycolic acid unbuffered; Jessner’s; Jessner’s + 20% to 35% TCA; Hetter VL (phenol) |

| Deep | ≥ 400 | Hetter all around; Stone 100 (grade 2); Exoderm-Lift |

TCA, trichloroacetic acid

• Tretinoin peeling

Premixed Commercial Combination Peels

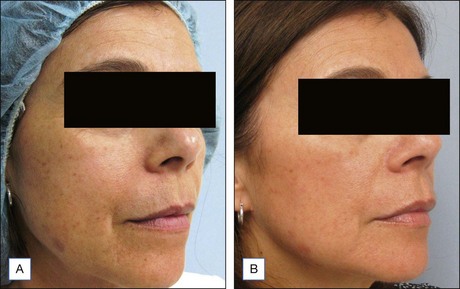

The Vi Peel™ is recommended for use in darker skin types. The Vi Peel™ is available as a premixed formula containing TCA (9% in alcohol), phenol (9%), salicylic acid (9%), tretinoin (0.1%), and 4% vitamin C (with two night applications of towlettes with the same percentage of tretinoin and vitamin C) (Figures 9.1, 9.2). This peel is self-neutralizing.

The Melanage Peel™, designed for dark skin types with melasma or PIH, is commercially available as a kit (Figures 9.3 to 9.5). The kit includes a 1% tretinoin solution and a powder formulation of hydroquinone, which is mixed fresh at the time of use with 10% azelaic acid, 10% lactic acid, and 10% phytic acid. The peel is applied as a mask in the clinic and removed by the patient at home. Dermatologists can also make up to a 14% hydroquinone peel, which is left for up to 8 hours on the skin. The key features of this peel are that it is weakly acidic, noncorrosive, minimally inflammatory, and causes no protein precipitation. This peel can be performed once yearly, and can be followed by a series of 3 to 4 minipeels during the year. The kit also includes a ready-to-mix bleaching cream consisting of a 4% hydroquinone with 0.025% tretinoin or a percentage chosen by the physician to be applied nightly for 2 months.

Treatment Techniques

• Materials

• Treatment algorithm

Procedure for Superficial Peels

The label on the bottle must be precisely checked before applying the peel.

• Side effects, complications, and alternative approaches

The potential complications of chemical peels are listed in Box 9.3.

Scarring

Box 9.4

Rullan, Dumet and Hexsel’s 10 secrets to better peels in darker skin types

Case Studies

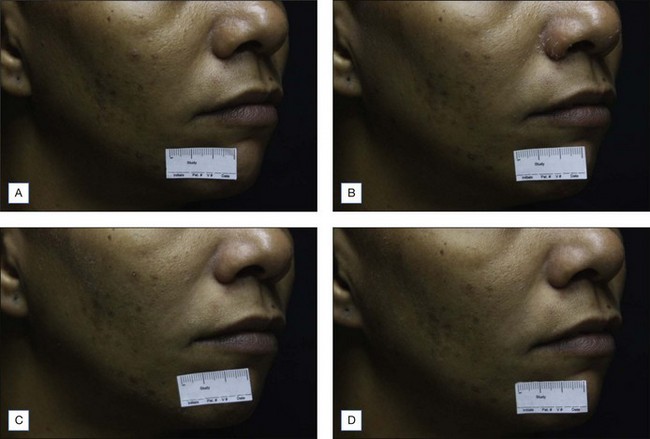

Figure 9.6 Mild superficial peeling. Seven days of follow up. (A) Day 0; (B) day 3; (C) day 5; and (D) day 7

Berardesca E, Maibach H. Ethnic skin: overview of structure and function. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2003;48(6 Suppl):S139-S142.

Clark E, Scerri L. Superficial and medium-depth chemical peels. Clinics in Dermatology. 2008;26:209-218.

Fischer TC, Perosino E, Poli F, et al. Chemical peels in aesthetic dermatology: an update 2009. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 2010;24(3):281-292.

Grimes PE. The safety and efficacy of salicylic acid chemical peels in darker racial-ethnic groups. Dermatological Surgery. 1999;25:18-22.

Grimes PE. Agents for ethnic skin peeling. Dermatologic Therapy. 2000;13:159-164.

Javaheri SM, Handa S, Kaur I, et al. Safety and efficacy of glycolic acid facial peel in Indian women with melasma. International Journal of Dermatology. 2001;40:354-357.

Khunger N. Standard guidelines of care for chemical peels. Indian Journal of Dermatology Venereology Leprology. 2008;74(Suppl):S5-S12.

Khunger N, Sarkar R, Jain RK. Tretinoin peels versus glycolic acid peels in the treatment of melasma in dark-skinned patients. Dermatological Surgery. 2004;30:756-760.

Lee HS, Kim IH. Salicylic acid peels for the treatment of acne vulgaris in Asian patients. Dermatologic Surgery. 2003;29:1196-1199.

Mendelsohn JE. Update on chemical peels. Otolaryngology Clinics of North America. 2002;35:55-72.

Revis DR, Seagle MB. Skin resurfacing: chemical peels. Available at URL. http://www.emedicine.com/ent/topic625.htm, 2005.

Roberts WE. Chemical peeling in ethnic/dark skin. Dermatologic Therapy. 2004;17:196-205.

Rullan P, Lemmon J, Rullan JM. The 2-day phenol chemabrasion technique for deep wrinkles and acne scars. Americal Journal of Cosmetic Surgery. 2004;21:199-210.

Rullan P, Karam A. Chemical peels for darker skin types. Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America. 2010;18(1):111-131.

Sarkar R, Kaur C, Bhalla M, et al. The combination of glycolic acid peels with a topical regimen in the treatment of melasma in dark-skinned patients: a comparative study. Dermatologic Surgery. 2002;28:828-832.

The American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. Statistics on Cosmetic Surgery. 2008. New York. http://www.surgery.org/sites/default/files/2008stats.pdf, 2008.