57 Pedicle Screw Fixation in the Aging Spine

KEY POINTS

Introduction

In current clinical practice, the large majority of posterior instrumentation spinal surgeries involve pedicle screw instrumentation. In the osteoporotic spine, the weak link in the instrumentation construct is the implant–bone interface. The majority of instrumentation failures involve screw loosening and pull-out, which may lead to failure of fusion or the development of recurrent or de novo deformity. Posterior thoracolumbar instrumentation failure has been shown to correlate with bone mineral density (BMD).1–3 Screw pull-out and also cutout through the adjacent endplate with cyclical flexion–extension loading are directly related to BMD and may occur even at physiologic loads in the osteoporotic spine.1–3 In a biomechanical study, Soshi and colleagues2 concluded that pedicle screw fixation should be avoided in patients with a BMD less than 0.3 g/cm2.

At the time of pedicle screw insertion, the surgeon may recognize poor screw purchase in osteoporotic bone because of the low insertion torque required to advance the screw. Insertion torque not only correlates with BMD and screw pull-out, but also predicts early screw failure.4–6 If poor screw purchase is recognized intraoperatively, the surgeon should attempt to salvage the situation rather than rely on inadequate fixation to achieve the goals of instrumentation.

Pedicle Screws in the Osteoporotic Spine

Screw Placement

The surgeon may consider increasing the length or diameter of the pedicle screw in an attempt to improve the screw purchase in bone (Table 57-1). Increasing screw length does increase screw pull-out strength, although this effect may be less pronounced in osteoporotic bone.7,8 Use of bicortical screws in the lumbar spine is limited because of risk of vascular injury. However, in the sacrum, a bicortical screw can be placed safely and improves pull-out strength.9,10 The inability to accurately gauge the anterior vertebral body cortex intraoperatively may affect the surgeon’s ability to safely place longer screws, since screws extending beyond the anterior vertebral body may predispose to vascular injury. At the sacrum, bicortical purchase may be safely accomplished with medially directed pedicle screws with a low risk of vascular injury. Increasing screw diameter will also increase pull-out strength7,11–13; however, the dimensions of the pedicle being cannulated may limit the screw diameter. In the osteoporotic spine, when the screw diameter exceeds 70% of the pedicle diameter, a risk of pedicle fracture is created.14

| Screw Size | 6.0 | 5.0 |

|---|---|---|

| Screw outer diameter (mm) | 6.0 | 5.0 |

| Screw minor diameter (mm) | 4.8 | 3.8 |

| Tap minor diameter (mm) | 4.75 | 3.75 |

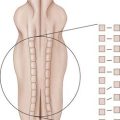

Directing pedicle screws toward the stronger subchondral bone adjacent to the vertebral body endplate will improve pull-out resistance.15,16 In the sacrum, optimal screw purchase is achieved by directing the screws toward the disc space anteriorly or through the sacral promontory.17–19

Another strategy to improve stability of the pedicle screw construct in osteoporotic bone is to distribute forces by increasing the number of fixation points to the spine by including additional levels in the construct. The advantages of this approach must be weighed against the risks and morbidity associated with the additional level surgery as well as the potential long-term consequences of a fusion spanning additional levels. The surgeon may also augment the pedicle screw construct with offset sublaminar hooks, which are well suited for use in the osteoporotic spine because they rely on the relatively unaffected cortical laminar bone for fixation.1,20 Biomechanical studies have supported the ability of supplemental sublaminar hooks to increase the rigidity and pull-out strength of pedicle screw constructs.21,22

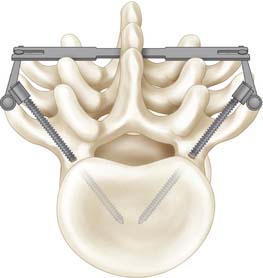

Convergence of pedicle screws with a triangulation effect can substantially increase the overall pull-out strength of the construct and provides higher resistance against loads perpendicular to the pedicle screw (Figure 57-1).23 Triangulation of pedicle screws increased pullout strength by 143% over single pedicle screws.23 Bilateral triangulated pedicle screws allow the screws to, in effect, hold all of the bone between the screws rather than just the bone within the threads of the individual screws. Ruland and colleagues23 suggested that for triangulated screws to fail simultaneously, a transverse fracture through the vertebral body at the level of the tips of the pedicle screw had to occur. Kilincer and colleagues24 demonstrated there was no biomechanical benefit to converging pedicle screws more than 60 degrees.

Undertapping Pedicle Screws

In osteoporotic bone, loss of fixation at the bone–screw interface is the primary mode of failure for screws. The preparation technique of the bone–implant interface is important for optimal screw purchase. Typically the path for the pedicle screw is tapped before screw placement. In osteoporotic bone, a tap with a diameter smaller than that of the pedicle screw is recommended in order to conserve cancellous bone, which is compacted around the screw heads thereby increasing screw stability. Carmouche and colleagues25 performed a cadaveric pullout resistance study comparing tapping, undertapping, and no-tapping techniques. The authors reported that same-size tapping of lumbar and thoracic pedicle screws decreased pullout resistance when compared to undertapping or no-tapping. Kuklo and colleagues26 reported a 93% increase in insertional torque when undertapping thoracic screws by 1 mm when compared to line-to-line tapping. Halvorson found in a cadaveric model that screw insertion technique did not affect pullout resistance with normal bone density (BMD > 1 g/cm2).27 In osteoporotic bone, however, there was a marked benefit to undertapping by 1 mm.27,28

Transverse Connectors

Transverse connectors, also known as “cross-links”, serve to link together and add rigidity to two screw–rod constructs (Figure 57-2). The cross-link does not directly effect fixation at the screw-bone interface, but instead augments stability of the overall construct that can indirectly facilitate fixation by minimizing micro motion. Biomechanical testing has confirmed the ability of cross-links to increase torsional and lateral stability in an unstable burst fracture model. An additive effect to stability with the application of one and then two cross-links was reported.29 Transverse connectors had little effect on flexion-extension, lateral bending or tensile rod stress. Longer constructs such as those used to treat spinal deformity have also been tested with cross-links. Kuklo and colleagues30 showed that in long pedicle screw–rod constructs, cross-links increased predominantly axial rotational stability, with the effect enhanced by the addition of a second cross-link (additional 15%). Location of the cross-link within the longer constructs did not significantly impact stability.

Disadvantages of cross-links include breakage31 and hardware prominence because these are the most dorsally placed elements in the instrumentation construct. The dorsal cross-link prominence may lead to localized discomfort and at times the formation of an overlying bursa. Additionally, connectors can theoretically add to instrumentation crowding, thus reducing available bone surface area for fusion.

Bone Cement

The bone–screw interface also may be improved by injecting polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) bone cement into the pedicle around the pedicle screw. A twofold to threefold increase in screw pullout has not been demonstrated with the use of PMMA injected into the vertebral body through a cannulated pedicle.2,8 Increasing the amount of PMMA injected into the pedicle has not been shown to significantly increase the pullout strength.32 Possible risks of this technique include cement extravasation outside of the vertebra, with potential for leakage into the spinal canal or neural foramina. Other cements such as hydroxyapatite cement, calcium phosphate, and carbonated apatite have also been shown to enhance the screw–bone interface and increase pedicle screw pullout strength.13,33,34 Moore and colleagues33 reported that the failure modes seen with PMMA and calcium phosphate cement differed in pullout tests. With PMMA augmentation, pedicle fracture occurred at or near the junction with the vertebral body in 80% (25 of 30) of the samples. In contrast, failure of calcium phosphate augmentation occurred at the cement–screw interface in 80% (24 of 30) of the samples. In an in vivo animal model of pedicle screw augmentation, injectable calcium sulfate cement was shown to significantly improve the immediate pullout strength of pedicle screw fixation, and this effect was maintained even after the calcium sulfate cement had been absorbed completely.35 Interestingly Kiner and colleagues36 recently reported a biomechanical study suggesting that larger diameter pedicle screws increased construct rigidity greater than did cement augmentation. Cement augmentation of screws has been used in patients with osteoporosis and metastatic spinal tumors undergoing spinal instrumentation with acceptable clinical results and low rates of instrumentation failure.37–39

Expandable Screws

Various designs of expanding pedicle screws are available. In one design, the pedicle screw is cannulated to accept an expansion peg. The distal two thirds of the screw is split lengthwise by two perpendicular slots to form four anterior fins when expanded. An expansion peg (a smaller-gauge screw) is threaded into the inner core of the pedicle screw. As the expansion peg advances into the slotted portion of the screw, it spreads and opens up the slotted tip of the screw, creating fins. Withdrawal of the expansion peg collapses the fins, allowing for removal of the screw (Figure 57-3).

Ngu and colleagues40 examined the load-to-failure strength of an expandable screw design (Omega-21, Biomet, Warsaw, Ind.). The expandable-screw pullout strength (391 N) was significantly stronger than a standard pedicle screw l (145 N) reflecting a 170% increase in pullout strength. It should be noted in this study that cemented augmented pedicle fixation had an even higher pullout resistance (599 N, or 284% increase). Cook and associates41 found expandable screws to have an approximate 50% increase in pullout strength compared with conventional pedicle screws.

1. Coe J.D., Warden K.E., Herzig M.A. Influence of bone mineral density on the fixation of thoracolumbar implants. A comparative study of transpedicular screws, laminar hooks, and spinous process wires. Spine. 1990;15:902-907.

2. Soshi S., Shiba R., Kondo H. An experimental study on transpedicular screw fixation in relation to osteoporosis of the lumbar spine. Spine. 1991;16:1335-1341.

3. Yamagata M., Kitahara H., Minami S. Mechanical stability of the pedicle screw fixation systems for the lumbar spine. Spine. 1992;17:S51-S54.

4. Lu W.W., Zhu Q., Holmes A.D. Loosening of sacral screw fixation under in vitro fatigue loading. J. Orthop. Res.. 2000;18:808-814.

5. Okuyama K., Sato K., Abe E. Stability of transpedicle screwing for the osteoporotic spine. An in vitro study of the mechanical stability. Spine. 1993;18:2240-2245.

6. Zdeblick T.A., Kunz D.N., Cooke M.E. Pedicle screw pullout strength. Correlation with insertional torque. Spine. 1993;18:1673-1676.

7. Polly D.W.Jr., Orchowski J.R., Ellenbogen R.G. Revision pedicle screws. Bigger, longer shims—what is best? Spine. 1998;23:1374-1379.

8. Zindrick M.R., Wiltse L.L., Widell E.H. A biomechanical study of intrapedicular screw fixation in the lumbosacral spine. Clin. Orthop Relat Res. 203.. 1986:99-112.

9. McCord D.H., Cunningham B.W., Shono Y: Biomechanical analysis of lumbosacral fixation, Spine, 17 (Suppl):1992, S235-S243.

10. Mirkovic S., Abitol J.J., Steinman J: Anatomic consideration for sacral screw placement, Spine, 16 (Suppl):1991, S289-S294.

11. McLain R.F., McKinley T.O., Yerby S.A. The effect of bone quality on pedicle screw loading in axial instability. A synthetic model. Spine. 1997;22:1454-1460.

12. Brantley A.G., Mayfield J.K., Koeneman J.B. The effects of pedicle screw fit. An in vitro study. Spine. 1994;19:1752-1758.

13. Yerby S.A., Toh E., McLain R.F. Revision of failed pedicle screws using hydroxyapatite cement. A biomechanical analysis. Spine. 1998;23:1657-1661.

14. Hirano T., Hasegawa K., Washio T. Fracture risk during pedicle screw insertion in osteoporotic spine. J. Spinal Disord.. 1998;11:493-497.

15. Hadjipavlou A.G., Nicodemus C.L., al-Hamdan F.A., Simmons J.W., Pope M.H. Correlation of bone equivalent mineral density to pull-out resistance of triangulated pedicle screw construct. J. Spinal Disord.. 1997;10(1):12-19.

16. Lowe T., O’Brien M., Smith D. Central and juxta-endplate vertebral body screw placement: a biomechanical analysis in a human cadaveric model. Spine. 2002;27(4):369-373.

17. Robertson P.A., Plank L.D. Pedicle screw placement at the sacrum: anatomical characterization and limitations at S1. J. Spinal Disord.. 1999;12(3):227-233.

18. Lu W.W., Zhu Q., Holmes A.D., Luk K.D., Shong S., Leong J.C. Loosening of sacral screw fixation under in vitro fatigue loading. J. Orthop. Res.. 2000;18(5):808-814.

19. Lehman R.A.Jr., Kuklo T.R., Belmont P.J.Jr., Andersen R.C., Polly D.W.Jr. Advantage of pedicle screw fixation directed into the apex of the sacral promontory over bicortical fixation: a biomechanical analysis. Spine. 2002;27(8):806-811. 98 (Suppl) (2003) 50–55

20. Chiba M., McLain R.F., Yerby S.A. Short-segment pedicle instrumentation. Biomechanical analysis of supplemental hook fixation. Spine. 1996;21:288-294.

21. Hasegawa K., Takahashi H.E., Uchiyama S. An experimental study of a combination method using a pedicle screw and laminar hook for the osteoporotic spine. Spine. 1997;22:958-962. discussion 963

22. Hilibrand A.S., Moore D.C., Graziano G.P. The role of pediculolaminar fixation in compromised pedicle bone. Spine. 1996;21:445-451.

23. Ruland C.M., McAfee P.C., Warden K.E. Triangulation of pedicular instrumentation. A biomechanical analysis. Spine. 1991;16(Suppl. 6):S270-S276.

24. Kilincer C., Inceoglu S, Sohn M.J., et al. Effects of angle and laminectomy on triangulated pedicle screws. J. Clin. Neurosci.. 2007;14(12):1186-1191.

25. Carmouche J.J., Molinari R.W., Gerlinger T., Devine J., Patience T. Effects of pilot hole preparation technique on pedicle screw fixation in different regions of the osteoporotic thoracic and lumbar spine. J. Neurosurg. Spine. 2005 Nov.;3(5):364-370.

26. T.R. Kuklo, R.A. Lehman, Jr. Effect of various tapping diameters on insertion of thoracic pedicle screws: a biomechanical analysis. Spine 28 (18): 2066–2071.

27. Halvorson T.L., Kelley L.A., Thomas K.A. Effects of bone mineral density on pedicle screw fixation. Spine. 1994;19(21):2415-2420.

28. Pfeiffer F.M., Abernathie D.L., Smith D.E. A comparison of pullout strength for pedicle screws of different designs: a study using tapped and untapped pilot holes. Spine. 2006 Nov 1;31(23):E867-E870.

29. Dick J.C., Zdeblick T.A., Bartel B.D. Mechanical evaluation of cross-link designs in rigid pedicle screw systems. Spine. 1997;22:370-375.

30. Kuklo T.R., Dmitriev A.E., Cardoso M.J., Lehman R.A.Jr., Erickson M., Gill N.W. Biomechanical contribution of transverse connectors to segmental stability following long segment instrumentation with thoracic pedicle screws. Spine. 2008 Jul 1;33(15):E482-E487.

31. Eck K.R., Bridwell K.H., Ungacta F.F., Riew K.D., Lapp M.A., Lenke L.G., Baldus C., Blanke K. Complications and results of long adult deformity fusions down to l4, l5, and the sacrum. Spine. 2001 May 1;26(9):E182-E192.

32. Frankel B.M., D’Agostino S., Wang C. A biomechanical cadaveric analysis of polymethylmethacrylate-augmented pedicle screw fixation. J. Neurosurg. Spine. 2007 Jul;7(1):47-53.

33. Moore D.C., Maitra R.S., Farjo L.A. Restoration of pedicle screw fixation with an in situ setting calcium phosphate cement. Spine. 1997;22:1696-1705.

34. Lotz J.C., Hu S.S., Chiu D.F. Carbonated apatite cement augmentation of pedicle screw fixation in the lumbar spine. Spine. 1997;22:2716-2723.

35. Yi X., Wang Y., Lu H., Li C., Zhu T. Augmentation of pedicle screw fixation strength using an injectable calcium sulfate cement: an in vivo study. Spine. 2008 Nov 1;33(23):2503-2509.

36. Kiner D.W., Wybo C.D., Sterba W., Yeni Y.N., Bartol S.W., Vaidya R. Biomechanical analysis of different techniques in revision spinal instrumentation: larger diameter screws versus cement augmentation. Spine. 2008;33(24):2618-2622.

37. Wuisman P.I., Van Dijk M., Staal H. Augmentation of (pedicle) screws with calcium apatite cement in patients with severe progressive osteoporotic spinal deformities: An innovative technique. Eur. Spine J.. 2000;9:528-533.

38. Jang J.S., Lee S.H., Rhee C.H. Polymethylmethacrylate-augmented screw fixation for stabilization in metastatic spinal tumors. Technical note. J. Neurosurg.. 2002;96:131-134.

39. Chang M.C., Liu C.L., Chen T.H. Polymethylmethacrylate augmentation of pedicle screw for osteoporotic spinal surgery: a novel technique. Spine. 2008 May 1;33(10):E317-E324.

40. Ngu B.B., Belkoff S.M., Gelb D.E., Ludwig S. A biomechanical comparison of sacral pedicle screw salvage techniques. Spine. March 15, 2006;31(6):E166-E168.

41. Cook S.D., Barbera J., Rubi M., Salkeld S.L., Whitecloud T.S. Lumbosacral fixation using expandable pedicle screws. an alternative in reoperation and osteoporosis. Spine J.. 2001 Mar-Apr;1(2):109-114.