Pediatric ultrasound-guided vascular access

General considerations and ultrasound evaluation of peripheral and central veins in pediatric patients (preprocedural scanning)

Ultrasound offers the advantage of preprocedural evaluation of all possible venipuncture sites as detailed in previous chapters. This is an essential feature of the ultrasound method when applied in the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU).1–4 A thorough ultrasound examination allows the identification of vessels that may be difficult to puncture (e.g., small vessel diameter, especially in relation to the size of the catheter used; vessels collapsing during breathing; vessels in close proximity to arteries or the pleura; or the presence of thrombosis, hematomas, strictures, or anatomic variations). Ideally, the external diameter of the catheter should not exceed a third of the internal diameter of the vein (e.g., a 3-Fr catheter should be inserted into a vein with an internal diameter of 3 mm [≥9 Fr = 3 mm] as measured by ultrasound, a 4-Fr catheter would require a 4-mm vein, and so on).3 In the PICU, preprocedural scanning may optimize the choice of catheter type (e.g., peripherally inserted central catheter [PICC] vs. a centrally inserted venous catheter) or puncture site (venous segments of the superior vs. the inferior vena cava network) and thus facilitate real-time ultrasound-guided catheterization of the vessel.

Implementation of the holistic approach (HOLA) to ultrasound scanning facilitates fast and detailed exploration of all venous circuits in pediatric patients3 (see Chapters 1 and 47). Preprocedural scanning starts with examination of the superficial and deep veins of both arms. When central venous access is needed, the forearm veins can be ignored and the evaluation may start directly at the antecubital area, where the cephalic vein is generally visible on the radial border. The brachial artery is located medially, and one or more brachial veins are usually identified adjacent to the artery. Approximately halfway between the elbow and axilla the veins can be more carefully evaluated for possible cannulation. The most easily accessible vein at this level is the basilic vein, which lies superficial and medial to the brachial veins. As the basilic vein approaches the axillary area, it progressively merges with the brachial veins to form the axillary vein. In the PICU, cannulation of the basilic vein is a preferable option because this vein is larger and located more distantly in relation to the artery and the median nerve than the brachial veins are. The cephalic vein is usually a poor choice for cannulation because it is superficial, small, and tortuous.5 However, all upper extremity veins should be evaluated sonographically in terms of (1) internal diameter, (2) depth (distance from the surface of the skin), (3) regularity of trajectory (a tortuous vein or a vessel with a sudden bend is a bad choice for cannulation), (4) proximity to other anatomic structures that may be accidentally punctured (e.g., brachial artery, median nerve), and (5) any preexistent abnormalities (e.g., thrombosis, anatomic variations). Two-dimensional, color Doppler, and compression ultrasonography techniques can all be applied to investigate the aforementioned parameters.2 When the patient is hypovolemic or the veins are smaller than expected, the sonographic examination should be repeated after placement of a tourniquet (quite tightened and placed at the axilla). The minimum size of venous catheter available for ultrasound-guided insertion is 3 Fr. When no arm vein reaches a diameter of 3 mm, cannulation should not be attempted in this area. Interestingly, neonates and small infants rarely have deep arm veins larger than 2 mm. Occasionally, some infants might have an axillary vein with a diameter of 3 mm or larger (at the level of the axilla).

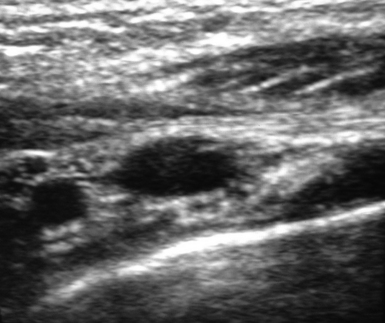

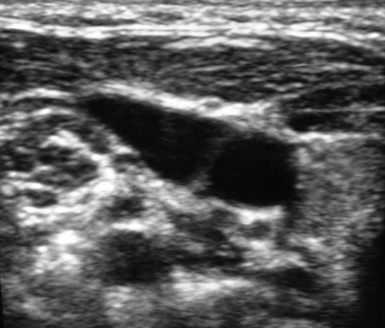

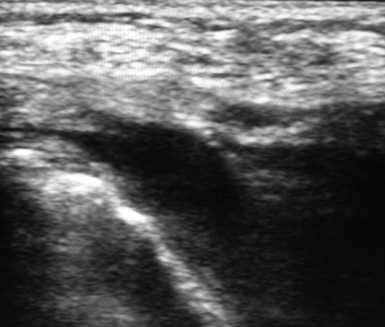

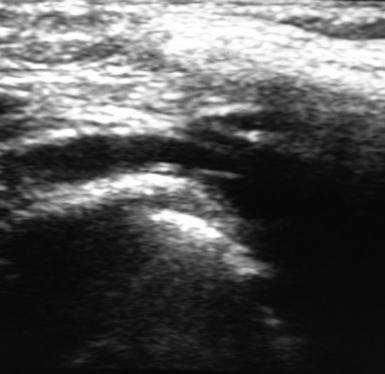

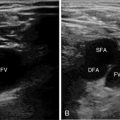

Preprocedural scanning continues by exploration of the infraclavicular area to visualize the axillary vessels in both the transverse and longitudinal planes (Figures 13-1 and 13-2). In this area the cephalic vein can be also evaluated at its union with the axillary vein. In children, both the axillary and cephalic veins can be cannulated quite easily at this level. In neonates and infants, these veins are usually too small for cannulation, although exceptions might occur, as mentioned in previous paragraphs. Scanning of the supraclavicular area starts at the middle of the neck by sweeping the transducer in a transverse plane over the internal jugular vein (IJV) and the common carotid artery (Figures 13-3 and 13-4). At this level the IJV is evaluated in terms of diameter, extent of collapse during breathing, position relative to the artery, presence of valves, and possible abnormalities (e.g., thrombosis, hypoplasia). By sweeping the transducer downstream (along the IJV trajectory) toward the lower neck region, the subclavian artery can be visualized as a major arterial segment that lies deeper than the IJV and in transverse alignment with the IJV trajectory. Next, the transducer reaches the suprasternal notch, where it can be tilted in a frontal orientation to scan the anterior mediastinum, at which point the brachiocephalic vein (almost longitudinal plane) is visualized (Figures 13-5 and 13-6). In neonates, the brachiocephalic vein is often the easiest and safest vein to cannulate because of its large diameter. By sweeping the transducer laterally (above the superior clavicular border) the subclavian vein (longitudinal plane) is visualized (Figures 13-7 and 13-8). In this area, especially in neonates and infants, the deep tract of the external jugular vein (longitudinal axis) becomes visible as a compressible structure that lies posterosuperior and parallel to the subclavian vein. Hence external jugular venipuncture may be easier and safer than subclavian venipuncture in view of the close proximity of the latter to the pleura. Once again, preprocedural scanning should evaluate all the aforementioned venous circuits (which are accessed in the neck area) in terms of diameter, distance from the surface of the skin, possible abnormalities, and other parameters as mentioned in previous paragraphs. Finally, the lower extremity is scanned accordingly only in the upper part of the thigh and the groin area. The most suitable veins for cannulation are usually the femoral and saphenous veins. Nevertheless, both veins can indeed be very small in underweight neonates and thus not suitable for cannulation. Ultrasound-based evaluation of all peripheral and central veins, which represent potential catheterization “targets,” is performed bilaterally. In expert hands a complete ultrasound examination may require just 2 minutes. Next, the same strictly aseptic, real-time ultrasound-guided method used in adults is also applied in children to obtain central venous access; however, various technical differences do exist.

Instrumentation and kits used for ultrasound-guided catheterization in neonates and children

Transducer

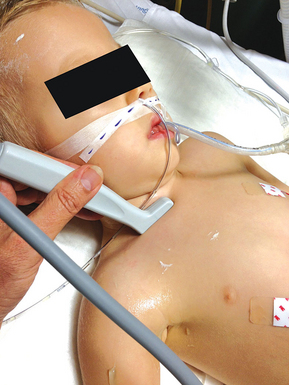

Neonates and infants ideally require a high-frequency linear transducer (10 to 20 MHz), which will offer the best resolution at a depth of 2 cm from the surface of the skin. In older children, lower-frequency transducer with small footprints may occasionally be used (e.g., microconvex). Transducers bearing small footprints are preferred in pediatric patients. The shape of the transducer is also relevant (e.g., the neck of a neonate is particularly short and thus the supraclavicular venous segments are best explored with a “hockey stick”–shaped transducer).1,3,5

Needle

In pediatric patients, both peripheral and central veins should be punctured only with 21-gauge echogenic needles (appropriately sharpened). Needle length is in the range of 3.5 to 6 cm, although the central veins of a neonate should preferably be punctured with the smallest available needles.2

Guidewire

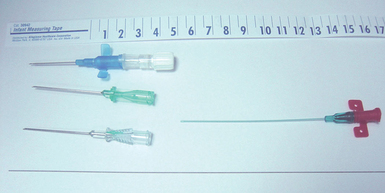

J-shaped guidewires should not be used in pediatric patients for either peripheral or central cannulation.6 The guidewire must have a straight floppy tip so that it is less atraumatic and thus easily guided in the lumen of the vessel. When 21-gauge needles are used, 0.018-inch guidewires are needed. Nitinol (nickel plus titanium) is currently regarded as the material of choice for small-gauge guidewires.3 In neonates, use of separate 22- to 24-gauge cannulas and baby wires instead of the central line introducer kit is helpful (Figure 13-9).

Microintroducer and dilator

All ultrasound-guided insertions of central venous catheters in pediatric patients should be performed according to the indirect or “modified” Seldinger technique. This implies the use of a microintroducer and dilator of appropriate length (5 to 7 cm) and stiffness to facilitate smooth transition of the introducer, dilator, and guidewire. The microintroducer and dilator are inserted over the guidewire; next, the dilator and guidewire are simultaneously removed and the catheter is threaded into the introducer (most introducers are removed by a peel-away mechanism).3,5

Catheter

Polyurethane and silicone catheters are commonly used in neonates, infants, and children for both central and peripheral cannulation. Polyethylene catheters are too rigid and are therefore considered only for arterial cannulation. There are no differences between polyurethane and silicon catheters in terms of infection or thrombosis risk according to the current literature. Silicon catheters are more fragile than polyurethane catheters and prone to accidental rupture and dislocation. Power-injectable polyurethane is rapidly becoming the best option in terms of material since it is highly biocompatible, resistant to mechanical trauma, and less prone to obstruction. Moreover, it allows high-flow (2 to 5 mL/sec) and high-pressure (e.g., contrast agents) infusions. The most usual catheters inserted under ultrasound guidance in children are 3-Fr single-lumen, 4-Fr single- or double-lumen, and 5-Fr single- or double-lumen catheters. When small catheters are used, it is advisable to choose a power-injectable polyurethane catheter to maintain high infusion flow.3–5

Technique of ultrasound-guided central venous catheterization in neonates and small infants (younger than 3 months)

The IJV is generally preferred over the subclavian vein as a cannulation site in neonates and small infants,7–9 mainly because of the higher incidence of pneumothorax and subclavian artery puncture associated with the latter. In contrast, IJV cannulation has traditionally been linked with a low incidence of mechanical complications in pediatric patients. However, carotid artery puncture still represents a major complication, especially when an out-of-plane technique is used for ultrasound-guided IJV cannulation. No preferred puncture site for IJV cannulation exists because this is largely individualized.3,5,10 However, the transducer is usually angled at 25 degrees, and a focal length of 15 mm from the skin surface should be used. Real-time ultrasound-guided IJV cannulation should be performed with a hands-free technique.10 Needle guides are generally avoided, since the ideal entrance point for the needle is not certain because of the soft tissue variability observed in pediatric cases. The patient is usually placed in a slight Trendelenburg position (to increase the cross-sectional diameter of the vein), and the head is rotated 45 or 90 degrees to maintain the patient’s neck and thorax in the same plane. Other possible central venous access targets are the brachiocephalic or subclavian veins.11–13 Patients are placed in a slight Trendelenburg position with a rolled towel positioned under the shoulders. The head is rotated 30 degrees away from the venipuncture side, and the ipsilateral arm is gently pulled toward the knee. To puncture the brachiocephalic vein, the transducer is placed perpendicular to the skin on the neck’s side, and cross-sectional images of the IJV are obtained. Next, the trajectory of the IJV is followed until the junction of the subclavian vein and IJV is reached. At this level, by sweeping the transducer medially and caudally, longitudinal images of the subclavian and brachiocephalic veins are obtained. When operators aim to puncture the subclavian vein, the transducer is usually positioned over the clavicle to visualize its distal segment, which is traveling in the infraclavicular area, while pertinent transducer adjustments (e.g., tilting) are performed to depict an optimal longitudinal image of the vein at this level. The brachiocephalic and subclavian veins are commonly used for placement of central venous catheters in small infants and neonates.11–13

Technique of ultrasound-guided central venous catheterization in infants and small children (3 months to 6 years old)

The IJV remains the most frequently used access site for central venous catheterization in infants and children.14,15 No data suggest a higher rate of infection with IJV cannulation than with subclavian or brachiocephalic vein cannulation.2 IJV cannulation is generally avoided in patients with a tracheostomy or anatomic neck abnormalities. In the latter cases, brachiocephalic or subclavian vein cannulation is preferred. Cannulation of the brachiocephalic vein allows better fixation of the central venous catheter in the upper part of the thorax, the catheter can easily be tunneled, and thus the risk for infectious complications is minimized. Less frequent cannulation sites for obtaining central venous access are the femoral16 and axillary veins. The femoral vein is usually the preferred site for central venous cannulation in the emergency department because the coagulation state of the child is often unknown and a prompt fluid resuscitation may be necessary. The transducer is generally placed over the groin area and a transverse image of the femoral vein (and adjacent artery) is obtained; catheterization is commonly performed by the application of a fast-track, out-of-plane technique, especially when the child is hemodynamically unstable. As soon as the child is stabilized and transferred to the PICU, the central venous catheter should be removed from the femoral site and placed elsewhere to minimize the risk for infectious and mechanical complications.17 The axillary vein is an alternative option for central venous cannulation despite the fact that it is oftentimes small with a variable diameter during the respiratory cycle in pediatric patients.10 This may facilitate slow venous flow in a catheterized axillary vein, which could lead to the generation of thrombosis. Hence any central venous catheter in the axillary vein should be monitored regularly in the PICU. The catheter should be removed immediately in the event that a reduced vein-catheter diameter ratio of less than 70% is detected sonographically.

Technique of ultrasound-guided insertion of peripheral lines in pediatric patients

In terms of position of the tip of the catheter, venous access devices (VADs) can be classified as central (the tip is positioned in proximity to the junction of the superior vena cava and right atrium) or peripheral (the tip is positioned anywhere else in the venous system).3 Central VADs can be used for blood sampling, hemodynamic monitoring (e.g., central venous pressure, oxygen saturation of mixed venous blood), hemodialysis, and infusion of any kind of solution (including vesicant and phlebitogenic solutions). Peripheral VADs are not ideal for monitoring or blood sampling and can be used only for infusion of drugs with a pH of 5 to 9 and low osmolarity.

Inferior vena cava access devices

When the tip of a peripherally inserted catheter is positioned in the inferior vena cava (preferably below the confluence of the renal veins), the catheter can be used as a central line for drug infusion; however, it obviously cannot be used for hemodynamic monitoring purposes.10 Inferior vena cava VADs are placed through the femoral or saphenous veins under ultrasound guidance according to the direct or indirect Seldinger technique. These catheters are made of polyurethane or silicon and have one or two lumens and appropriate length.

Peripherally inserted central venous catheters in children

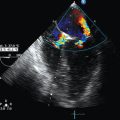

PICCs provide a relatively long-term vascular access option in pediatric patients. PICCs are VADs of adequate length (their tip is positioned adjacent to the cavoatrial junction, although their entry sites are located peripherally) that they can be used for the administration of total parenteral nutrition, prolonged intravenous antibiotic treatment, or chemotherapy.4,10 Home treatment of pediatric patients is facilitated since insertion of a PICC carries the benefit of lower infection rates and more convenient entry sites than is the case with other cannulas of shorter length inserted through arm veins. When placing a PICC, the operator can use a peel-away sheath, particularly with a small single-lumen catheter (e.g., 2 Fr) at the entry site. Implementation of the modified Seldinger technique is more appropriate with larger catheters. Ultrasound is used to guide access to peripheral veins at the site of entry of the PICC. The latter can be advanced under fluoroscopic or ultrasound guidance, whereas the position of the tip of the catheter can be confirmed sonographically by injection of contrast agents or agitated saline.

Pearls and highlights

• Select a high-frequency transducer with a small footprint when attempting to cannulate a pediatric patient.

• During preprocedural scanning, two-dimensional, color Doppler, and compression ultrasound techniques are usually applied to identify a patent target vein and adjacent structures (e.g., artery, nerve) in the region of interest.

• Preprocedural scanning according to the HOLA ultrasound concept facilitates detailed and fast exploration of all venous circuits.

• The same strictly aseptic, real-time ultrasound-guided method used in adults is applied in children to obtain central venous access. However, various technical differences do exist.

• Power-injectable polyurethane catheters are rapidly becoming the best option in terms of material because of their high biocompatibility and resistance to mechanical trauma. These catheters are less prone to obstruction and allow high-flow (2 to 5 mL/sec) and high-pressure (e.g., contrast agents) infusions.

• Neonates and small infants rarely have deep arm veins larger than 2 mm.

• The brachiocephalic and subclavian veins are commonly used for placement of central venous catheters in small infants and neonates.

• The IJV remains the most frequently used access site for central venous catheterization in infants and children.

• The femoral vein is generally the preferred site for central venous cannulation in the emergency department because the coagulation state of the child is often unknown and prompt fluid resuscitation may be necessary

• In pediatric patients, short, midline, and inferior vena cava VADs are usually considered as peripheral lines, whereas PICCs provide a relatively long-term vascular access option.

References

1. Asheim, P, Mostad, U, Aadahl, P. Ultrasound-guided central venous cannulation in infants and children,. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2002; 46:390–392.

2. De Jonge, RCJ, Polderman, KH, Reinoud, JBJ, Gemke, RJ, Central venous catheter use in the pediatric patient: mechanical and infectious complications. Pediatr Crit Care Me. 2005; 6:329–339.

3. Pittiruti, M, Hamilton, H, Biffi, R, et al, ESPEN guidelines on parenteral nutrition: central venous catheters (access, care, diagnosis and therapy of complications). Clin Nut. 2009; 28:365–377.

4. Detaille, T, Pirotte, T, Veyckemans, F. Vascular access in the neonate. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2010; 24:403–418.

5. Di Nardo, M, Tomasello, C, Pittiruti, M, et al. Ultrasound-guided central venous cannulation in infants weighing less than 5 kilograms. J Vasc Access. 2011; 12:318–320.

6. Sayin, M, Mercan, A, Koner, O, et al, Internal jugular vein diameter in pediatric patients: are the J-shaped guidewire diameters bigger than internal jugular vein? An evaluation with ultrasound. Paediatr Anaest. 2008; 18:745–751.

7. Pirotte, T, Ultrasound-guided vascular access in adults and children: beyond the internal jugular vein puncture. Acta Anaesthesiol Bel. 2008; 59:157–166.

8. Lamperti, M, Caldiroli, D, Cortellazzi, P, et al. Safety and efficacy of ultrasound assistance during internal jugular vein cannulation in neurosurgical infants. Intensive Care Med. 2008; 34:2100–2105.

9. Breshan, C, Platzer, M, Jost, R, et al, Size of internal jugular vs subclavian vein in small infants: an observational, anatomical evaluation with ultrasound. Br J Anaest. 2010; 105:179–184.

10. Pittiruti, M. Ultrasound guided central vascular access in neonates, infants and children. Curr Drug Targets. 2012; 13:961–969.

11. Breshan, C, Platzer, N, Jost, R, et al. Consecutive, prospective case series of a new method for ultrasound-guided supraclavicular approach to the brachiocephalic vein in children. Br J Anaesth. 2011; 106:732–737.

12. Pirotte, T, Veyckemans, F, Ultrasound-guided subclavian vein cannulation in infants and children: a novel approach. Br J Anaest. 2007; 98:509–514.

13. Rhondali, O, Attof, R, Combet, S, et al, Ultrasound-guided subclavian vein cannulation in infants: supraclavicular approach. Paediatr Anaest. 2011; 21:1136–1141.

14. Patil, V, Jaggar, S, Ultrasound guided internal jugular vein access in children and infant: a meta-analysis. Paediatr Anaest. 2010; 20:475.

15. Lamperti, M, Cortellazzi, P, Caldiroli, D, Ultrasound-guided cannulation of IJV in pediatric patients: are meta-analyses sufficient. Paediatr Anaest. 2010; 20:373–374.

16. Iwashima, S, Ishikawa, T, Ohzeki, T. Ultrasound-guided versus landmark-guided femoral vein access in pediatric cardiac catheterization. Pediatr Cardiol. 2008; 29:339–342.

17. Baldwin, RT, Kieta, DR, Gallagher, MW. Complicated right subclavian artery pseudoaneurysm after central venipuncture. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996; 62:581–582.