23 Pediatric Trauma

• Trauma is the leading cause of death in children.

• Pediatric trauma victims have worse outcomes than adult victims do.

• Head trauma is the leading cause of death and disability from pediatric trauma, followed by thoracic and abdominal trauma.

• Children with life-threatening injuries may have little or no external evidence of trauma.

• Pediatric resuscitation equipment should be stored in an easily accessed, clearly labeled area in the emergency department.

• Pediatric medication dosing and treatment algorithms should be posted in the emergency department, and Broselow-Luten resuscitation tapes should be available.

Epidemiology

The report of the Institute of Medicine’s Committee on Future of Emergency Care, released in June 2006, identified a lack of pediatric emergency services as a significant problem facing the health care system in the United States.1 Trauma is the leading cause of death and disability in children and young adults.2

Pathophysiology

The anatomic characteristics of children predispose them to more significant injuries than adults would experience from similar trauma. The severity of pediatric head injury is related to the immature brain myelination, thin skulls, and larger head-to-body ratios in children. The bones and connective tissues of children are more pliable than those of adults, which can lead to potentially severe internal injuries with minimal external evidence of thoracoabdominal trauma. Because children have a greater ratio of surface area to volume, force can more easily be transferred to internal organs. Multiple trauma is common in children as a result of the smaller distance between vital structures. The sympathetic tone of a child is better than that of an adult, so a child’s blood pressure may be maintained despite large volume loss. Once a critical percentage of blood volume is lost (25%), a child’s blood pressure can drop precipitously, partly because of the inability of pediatric patients to change cardiac contractility and their dependence on the compensatory mechanisms of increased peripheral vascular resistance and heart rate. It should be noted that posttraumatic pediatric hypotension may also be an indicator of head injury rather than hemorrhage.3

Approach and Management

Breathing difficulty in children may be the sequelae of insults to the chest wall, lungs, heart, great vessels, or abdomen, as well as neurologic or muscular injuries. It may also result from the loss of ventilatory musculature, as with a cervical spine injury or respiratory muscle fatigue. Young children may have disordered ventilation secondary to gastric distention because considerable air is gulped into the stomach during crying.4

Disability must be assessed thoroughly. Mental status is evaluated with the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) or an AVPU (alert, verbal, painful, unresponsive) scale (Table 23.1). An age-appropriate examination should be performed to evaluate for neurologic deficits.

| CATEGORY | APPROPRIATE RESPONSE | INAPPROPRIATE |

|---|---|---|

| Alert | Normal interaction for age | Lethargic, irritable |

| Verbal | Responds to name | Confused, unresponsive |

| Painful | Withdraws from pain | Nonpurposeful movement or sound without localization of pain |

| Unresponsive | No response to verbal or painful stimuli | |

Exposure of the body immediately after the ABCs have been addressed is imperative in all pediatric trauma patients. Emergency personnel should briefly expose and roll (with precautions) the patient to assess for initially unapparent injuries, such as a puncture wound in the posterior aspect of the chest in a victim of assault. Because of the increased ratio of surface area to volume in children and a propensity for hypothermia, blankets and warmed intravenous fluids should be used to maintain normothermia. Whenever feasible, family presence, which has been shown to not impede pediatric trauma resuscitation, should be accommodated during resuscitation to comfort the child.5 The emergency practitioner should communicate with the child during the examination.

After exposure, the secondary survey should be performed. An AMPLE history (allergies, medications, past medical history, last meal, and events leading up to the patient’s arrival in the ED) is obtained, followed by a complete head-to-toe examination. Particular attention should be paid to the eyes, ears, mouth, axillae, hands, and genitals. The utility of rectal examination has recently been called into question. In particular settings where questionable neurologic deficits are present or rectal or urogenital trauma is evident, a rectal examination may prove useful. It should be selective to avoid unnecessary emotional stress in the child.6 In an unconscious intubated patient, an orogastric or nasogastric tube and Foley catheter should be placed. As part of the secondary survey, initial radiographs and laboratory studies should be selectively ordered to further investigate any history and physical findings.

![]() Priority Actions

Priority Actions

A = Airway control—bag-valve-mask ventilation, endotracheal intubation

B = Breathing—maximize ventilation

C = Circulation—stabilize hemodynamic status

D = Disability—evaluate mental status and perform a neurologic examination

E = Exposure—completely undress and examine the patient

F = “Fingers and Foleys”—selective nasogastric or orogastric tube, bladder catheter, vaginal and rectal examinations

Secondary survey: Head-to-toe physical examination and AMPLE history (allergies, medications, past medical history, last meal, and events leading up to the patient’s arrival in the emergency department)

Younger children, particularly infants, have little functional ventilatory reserve.7 Time is therefore of the essence in restoring oxygenation, ventilation, and circulation. The ABCs of resuscitation should be repeated if there is any change in the patient’s status.

The most common life- and limb-threatening injuries in children are those to the head, chest, and abdomen. In each of these areas, there are subtle but important clues to such injures (Box 23.1).

Box 23.1 Overview of Pediatric Trauma Management

Attend to the ABCs of resuscitation (airway, breathing, circulation) first. Connect the patient to a cardiac and oxygen saturation monitor; administer oxygen or secure the airway as needed.

Obtain intravenous or intraosseous access.

If the patient is hypotensive or tachycardic, administer normal saline in a 20-mL/kg bolus.

Roll the patient, perform a secondary survey, and recheck the vital signs.

If shock persists, additional intravenous access should be obtained (at least two large-bore intravenous lines), and a second 20-mL/kg bolus of normal saline should be administered.

Abdominal and thoracic ultrasonography, radiography, and laboratory studies should be performed as indicated.

If shock persists, transfuse packed red blood cells at 10 mL/kg, and continue evaluation for and treatment of life-threatening injuries.

Diagnostic Testing

Primary and Secondary Surveys

The ALARA (as low as reasonably achievable) principle should be applied to minimize exposure to radiation. The clinician should limit the number of CT scans performed and should make size-based adjustments to the radiation scanning parameters.8 Some investigators have questioned the need for portable radiographs of the cervical spine, chest, and pelvis to screen for injury in all trauma patients.4 As with trauma triage, it is advisable to err on the side of caution. These studies should be performed in all seriously injured patients or if the status of the spine, chest, or pelvis is at all uncertain. A more focal radiologic screening examination, as indicated by the history and findings on physical examination, may be considered in stable patients with normal mental status. Children younger than 2 years in whom child abuse is suspected must undergo a skeletal radiographic survey to diagnose occult or remote injuries.

![]() Documentation

Documentation

The following information should be documented:

History

Detailed mechanism of the injury (e.g., speed of the vehicle, height of the fall)

Circumstances of the injury (e.g., damage to the vehicle, type of weapon)

Time until arrival at the emergency department

Patient’s access to medications or exposure to drugs or toxins

Inconsistencies in the history between witnesses, particularly when child abuse is suspected

Pediatric Head Trauma

Key Points

Key Points

• Head trauma is responsible for 80% of pediatric trauma deaths.

• Cervical immobilization is required if head injury is suspected.

• The AVPU scale can be used in children as an alternative to the GCS score.

• Significant alterations in a child’s mental status should prompt early airway management and immediate CT of the brain.

• Declining mental status with suspected intracranial injury requires immediate neurosurgical evaluation or transfer of the patient to a facility with neurosurgical capability.

Cervical Spine Injury

Pathophysiology and Anatomy

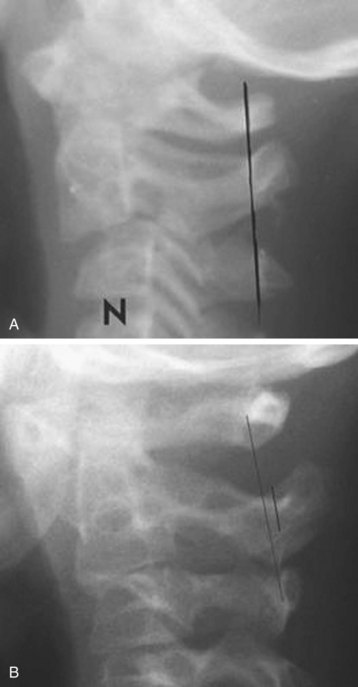

Mechanisms of fractures of the cervical spine in children are similar to those in adults, although children have a higher risk for ligamentous injuries (Box 23.2 and Fig. 23.1). Because the pediatric cervical spine is hypermobile, a traumatic injury can cause transient severe ligamentous disruption and lead to brief sensory or motor deficits or electric shocks with rapidly clearing weakness. The initial rapid resolution of symptoms represents realignment of structures with the counterforce of the injury such that the cord is drawn back into its anatomic position. Unfortunately, this phase can be followed by delayed neurologic deficits precipitated by cord edema after this stretch injury. The delay can be quite significant, with deficits appearing up to 4 days after the inciting event.

Box 23.2 Unique Characteristics of the Pediatric Cervical Spine

Incomplete ossification of the posterior elements

Predental space should not exceed 5 mm in children (3 mm in adults)

Pseudosubluxation at C2-C3 and C3-C4 (see Fig. 23.1)

Hypermobility or ligamentous laxity of the intervertebral ligaments

Horizontal orientation of the facet joints, which allows increased mobility and leads to:

Accentuated prevertebral soft tissue spaces, which should not exceed two thirds of the C2 body

Portions of the vertebra are radiolucent or wedge-shaped up to 8 years, which leads to widened disk spaces and anterior wedging

Anatomic fulcrum in children younger than 8 years between C1 and C3:

Diagnostic Testing

Plain Radiographs

The two studies most widely used to predict cervical spine injury, the Canadian C-Spine Study and the National Emergency X-Radiography Utilization Study, did not target the pediatric population.9 Though still requiring prospective validation, the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN) recently published an eight-variable model for predicting pediatric cervical spine injury: altered mental status, focal neurologic findings, neck pain, torticollis, substantial torso injury, congenital conditions predisposing to cervical spine injury, diving, and high-risk motor vehicle crash. The presence of one or more of these factors was 98% sensitive and 26% specific for cervical spine injury10 (Boxes 23.3 and 23.4).

Box 23.3 PECARN Data

Indications for Cervical Spine Radiography in Children

Complaint of neck pain (age > 2 years)

Conditions known to predispose to cervical spine injury*

Substantial injury to the torso (clavicles, abdomen, flanks, back including the spine, and pelvis)

High-risk motor vehicle crash (head-on collision, rollover, ejection from a vehicle, death in the same crash, or speed > 55 mph)

PECARN, Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network.

From Leonard JC, Kupperman N, Olsen C, et al, for The Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network. Factors associated with cervical spine injury in children after blunt trauma. Ann Emerg Med 2011;58:145-55.

* Down syndrome, Klippel-Feil syndrome, achondrodysplasia, mucopolysaccharidosis, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Marfan syndrome, osteogenesis imperfecta, Larsen syndrome, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile ankylosing spondylitis, renal osteodystrophy, rickets, history of CSI or cervical spine surgery.

Box 23.4 Tips for Reading Cervical Spine Radiographs in Children

Look for compression or widening of the intervertebral spaces.

Widening of the prevertebral soft tissue space should not be greater than one third to one half the width of the adjacent vertebral body in C1-C4 and not greater than a full vertebral body width for C5-C7.

Radiographs may be repeated with adequate inspiratory breath and neck positioning (not in flexion).

Treatment and Disposition

Immobilization with a cervical collar is required for any child with a cervical injury. When such an injury is diagnosed, emergency consultation with a pediatric spine surgeon and admission of the patient to the hospital are mandatory. Though still somewhat controversial, there is no evidence to recommend the use of high-dose methylprednisolone in the treatment of pediatric spinal cord lesions with neurologic deficits after blunt trauma.9

Pediatric Thoracic Trauma

Perspective

Trauma involving the chest is the second leading cause of death from trauma in children. The majority of cases are the result of blunt mechanisms. Associated injury is the most important mortality factor. The death rate from isolated chest trauma in children is 5%, whereas that from abdominal and chest trauma is 20% and that from trauma involving the head, chest, and abdomen is 39%.11

Clinical Presentation

Thoracic injuries account for 5% to 12% of admissions to pediatric trauma centers,12 but many children evaluated for chest trauma in the ED have much more subtle findings (Box 23.5). Children with chest pain, dyspnea, altered mental status, tachypnea, retractions, hypoxemia, shock, multiple-system trauma, or concern because of a high-risk mechanism should be evaluated for thoracic trauma. Injuries may occur in isolation or in combination with other thoracic or extrathoracic problems. Significant injuries may be present with little or no external evidence.

Diagnostic Testing

Chest Radiography

A chest radiograph is the most useful test in the evaluation of suspected chest trauma, although it is not as sensitive as CT scanning for many diagnoses, such as rib fracture, sternal fracture, pneumothorax, hemothorax, pulmonary contusion, and great-vessel injury. A chest radiograph should be obtained to confirm endotracheal position, identify intrathoracic causes of hypotension, exclude pneumothorax in patients with suggestive signs or symptoms (e.g., respiratory distress, crepitus, tenderness), or evaluate for external evidence of thoracic trauma.13

Specific Injuries

Pulmonary Contusion

Pulmonary contusion occurs in up to 71% of children with thoracic injuries.14 Because of the increased compliance of the rib cage in children, force is transferred directly to the lung parenchyma. Parenchymal hemorrhage and edema lead to alveolar collapse and disorders of gas exchange. Contusions large enough to impair respiratory function may occur without any external signs of trauma. Contusions may be immediately visible on chest radiographs or have a delayed appearance. The radiographic appearance of a pulmonary contusion ranges from minimal hazy opacity to a diffuse, dense infiltrate. The sensitivity of chest radiography for detection of pulmonary contusion was 67% in one study that used CT of the chest as the “gold standard.” Contusions not visible on chest radiographs were not clinically significant and did not require a change in management.15 Treatment of pulmonary contusion consists of pain control, pulmonary toilet, and mechanical ventilation when appropriate.

Pneumothorax

The primary screening examination is a chest radiograph, performed with the patient supine if the cervical spine has not been determined to be uninjured. It is an insensitive test for pneumothorax, with some estimates of sensitivity as low as 20% to 60%.16 An upright chest radiograph should be performed if possible. CT of the chest is extremely sensitive for the detection of pneumothorax, even very small ones that may need no intervention. Abdominal CT may demonstrate pneumothorax, but patients with pneumothorax detected only by this modality uncommonly need tube thoracostomy (Table 23.2).14 In adults, bedside ultrasonography has been shown to be comparable in specificity but more sensitive than chest radiography for the detection of traumatic pneumothorax.17

| SIZE | TREATMENT |

|---|---|

| More than 20% of the pleural space |

Data from Weissberg D, Refaely Y. Pneumothorax: experience with 1,199 patients. Chest 2000;117:1279–85.

Diaphragmatic Injury

The diagnosis of diaphragmatic injury is difficult. If significant abdominal contents have herniated into the thorax, the diaphragmatic injury may be diagnosed on screening chest radiography. Overall, sensitivity rates for both chest radiography and chest CT are not good. Sensitivity rates for CT of the chest in detecting blunt diaphragmatic rupture have been reported to be 42% to 90%. One study found that diaphragmatic injury was correctly diagnosed on admission in only 50% of patients admitted to a level I trauma center.18 Diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL) may have some utility in detecting diaphragmatic injury, although it is performed less frequently today than previously. Its sensitivity has been reported to be 80% in a selected population, although it is not specific. Because of the pressure differential between the abdomen and thorax, any missed defect in the diaphragm will continue to enlarge until it is repaired surgically.

Cardiac Contusion

A patient with a cardiac contusion may complain of chest pain or palpitations. External findings are sternal fracture, rib fracture, chest contusion, and sometimes no signs of trauma. The most common dysrhythmia is sinus tachycardia. The patient is unlikely to have complications if the findings on electrocardiography (ECG) are normal and the troponin level is normal over a 6- to 12-hour period of observation. In one study of pediatric blunt cardiac injury, no hemodynamically stable patient with a normal sinus rhythm subsequently demonstrated a cardiac arrhythmia or cardiac failure.19 Use of any changes on ECG, including sinus tachycardia, bradycardia, conduction delays, and atrial or ventricular dysrhythmias, can provide a sensitivity of 100%, a specificity of 47%, and a negative predictive value of 90% for the detection of complications related to blunt cardiac injury that require treatment. Several prospective series have demonstrated that if admission ECG displays normal sinus rhythm, the risk for development of cardiac complications related to blunt cardiac injury is extremely small.20,21

Pediatric Abdominal Trauma

Key Points

Key Points

• Abdominal trauma is the third leading cause of traumatic death in children.

• Most intraabdominal injuries are the result of blunt trauma.

• Missed intraabdominal injuries are a leading cause of preventable death.

• Children in whom intraabdominal injury is suspected are admitted to a pediatric trauma center.

Perspective

Motor vehicle accidents are the leading cause of abdominal trauma, although falls, sports accidents, and child abuse account for a significant number of injuries. Children struck by motor vehicles or who as motor vehicle passengers are not properly restrained or are ejected are at increased risk. Blunt trauma accounts for 90% of all pediatric injuries.22 Missed intraabdominal injury in the setting of blunt abdominal trauma is a leading cause of preventable mortality and morbidity in children.

Diagnostic Testing

Laboratory Values

Routinely ordering a full “trauma panel” of laboratory tests is not recommended for a child with abdominal trauma.23 In a hypotensive patient, blood typing plus cross-matching is the most important laboratory test to order early. In patients with a low risk for intraabdominal injury, urinalysis may be the only test with relatively high diagnostic yield. Few consistent data are available to support a recommendation for which laboratory tests to order for screening of children with low- to moderate-risk trauma for the presence of intraabdominal injury. In children with blunt abdominal trauma, Holmes et al. recently validated a six-variable prediction rule (94% sensitive and 37% specific) for indentifying intraabdominal injuries: low age-adjusted systolic blood pressure, abdominal tenderness, elevated hepatic enzymes (aspartate transaminase > 200 U/L or alanine transaminase > 125 U/L), urinalysis with more than five red blood cells per high-power field, initial hematocrit lower than 30%, and the presence of a femoral fracture.24

Focused Abdominal Ultrasonography for Trauma

The sensitivity of FAST in pediatric trauma is 55% to 82%.25–28 Its utility is higher in unstable patients. The finding of free fluid on FAST in stable pediatric patients rarely leads to operative management. The vast majority of children with such findings are observed and discharged with some restrictions in activity and appropriate return precautions. For this reason, an argument can be made that abdominal ultrasonography is less useful in pediatric trauma. One study found that using ultrasonography as a triage tool can reduce the cost of pediatric abdominal evaluation.29 Ultrasound allows the clinician to quickly identify significant intraperitoneal fluid that would require further evaluation and possible laparotomy. In this study, children with positive ultrasonographic findings who showed a response to initial fluid resuscitation underwent abdominal CT, and unstable patients underwent laparotomy. This approach allowed a major reduction in the number of CT scans performed. It has also been suggested but not proved that FAST, aside from being a screening tool, is sufficient for evaluation of the majority of children sustaining blunt abdominal trauma.

Computed Tomography

Abdominal CT should be performed in any stable patient in whom intraabdominal injury is suspected or to type and grade the injury in a patient with a positive FAST finding. Intravenous administration of a contrast agent is sufficient, and oral administration is not necessary (Box 23.7).30 CT findings allow the inpatient trauma service to select the appropriate level of inpatient care and monitoring for the patient.31 Although CT is excellent for evaluating solid organ injury, it is less sensitive for mesenteric, intestinal, and diaphragmatic injuries. If these latter injuries are suspected, further evaluation, such as admission to the hospital, serial abdominal examinations, and laboratory tests, are indicated.32 There are drawbacks to the routine performance of CT in any child in whom intraabdominal injury is suspected after trauma. CT is expensive, requires transport away from the direct caregiving environment, and may necessitate sedation of the child. In addition, computed risk estimates now suggest that CT may impose a higher lifetime risk for radiation-induced cancer in children than in adults.33 Use of the six-variable prediction rule by Holmes et al. (described earlier) has the potential to reduce unnecessary CT examinations by 30%.

Specific Injuries

The seat belt sign refers to ecchymoses, abrasions, or erythema caused by restraint by the seat belt across the abdomen during a motor vehicle accident.34 Its presence carries an increased risk for intraabdominal injuries, particularly to the intestines and pancreas. Proper, age-appropriate restraint of a child in an automobile is extremely important. Proper seat belt use does not increase the risk for injury, but use of just a lap belt does change the spectrum of injury.35 Other injuries associated with the use of lap belts are facial fractures and lumbar spine fractures termed Chance fractures.

1 Institute of Medicine, Committee on the Future of Emergency Care in the U.S. Health System. Hospital-based emergency care: at the breaking point. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006.

2 National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. WISQARS leading causes of death reports, 1999-2004. Available at http://webappa.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/leadcaus10.html/

3 Partrick DA, Bensard DD, Janik JS, et al. Is hypotension a reliable indicator of blood loss from traumatic injury in children? Am J Surg. 2002;184:555–560.

4 Avarello JT, Cantor RM. Pediatric major trauma: an approach to evaluation and management. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2007;5:803–836.

5 Dudley NC, Hansen KW, Furnival RA, et al. The effect of family presence on the efficiency of pediatric trauma resuscitations. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53:777–784.

6 Hankin AK, Baren JM. Should the digital rectal examination be a part of the trauma secondary survey? Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53:208–212.

7 Genevieve Santillanes G, Gausche-Hill M. Pediatric airway management. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2008;26:961–975.

8 Frush DP, Donnelly LF, Rosen NS. Computed tomography and radiation risks: what pediatric health care providers should know. Pediatrics. 2003;112:951–957.

9 Mathison DJ, Kadom N, Krug SE. Spinal cord injury in the pediatric patient. Clin Pediatr Emerg Med. 2008;9:106–123.

10 Leonard JC, Kupperman N, Olsen C, et al. Factors associated with cervical spine injury in children after blunt trauma. for The Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:145–155.

11 Balci EA, Kazez A, Eren S, et al. Blunt thoracic trauma in children: review of 137 cases. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004;26:387–392.

12 Bliss D, Silen M. Pediatric thoracic trauma. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:S409–S415.

13 Holmes JF, Sololove PE, Brant WE, et al. A clinical decision rule for identifying children with thoracic injuries after blunt torso trauma. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39:492–499.

14 Holmes JF, Brant WE, Bogren HG, et al. Prevalence and importance of pneumothoraces visualized on abdominal computed tomographic scan in children with blunt trauma. J Trauma. 2001;50:516–520.

15 Kwon A, Sorrells DL, Jr., Kurkchubasche AG, et al. Isolated computed tomography diagnosis of pulmonary contusion does not correlate with increased morbidity. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:78–82.

16 Bridges KG, Welch G, Silver M, et al. CT detection of occult pneumothorax in multiple trauma patients. J Emerg Med. 1993;11:179–186.

17 Kirkpatrick AW, Sirois M, Laupland KB, et al. Hand-held thoracic sonography for detecting post-traumatic pneumothoraces: the extended focused assessment with sonography for trauma (EFAST). J Trauma. 2004;57:288–295.

18 Nchimi A, Szapiro D, Ghaye B, et al. Helical CT of blunt diaphragmatic rupture. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:24–30.

19 Dowd MD, Krug S. Pediatric blunt cardiac injury: epidemiology, clinical features, and diagnosis. Pediatric Emergency Medicine Collaborative Research Committee: Working Group on Blunt Cardiac Injury. J Trauma. 1996;40:61–67.

20 Foil MB, Mackersie RC, Furst SR, et al. The asymptomatic patient with suspected myocardial contusion. Am J Surg. 1990;160:638–643.

21 Illig KA, Swierzewski MJ, Feliciano DV, et al. A rational screening and treatment strategy based on the electrocardiogram alone for suspected cardiac contusion. Am J Surg. 1991;162:537–543.

22 Potoka DA, Saladino RA. Blunt abdominal trauma in the pediatric patient. Clin Pediatr Emerg Med. 2005;6:23–31.

23 Keller MS, Coln CE, Trimble JA, et al. The utility of routine trauma laboratories in pediatric trauma resuscitations. Am J Surg. 2004;188:671–678.

24 Holmes JF, Mao A, Awasthi S, et al. Validation of a prediction rule for the identification of children with intra-abdominal injuries after blunt torso trauma. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:528–553.

25 Coley BD, Mutabagani KH, Martin LC. Focused abdominal sonography for trauma (FAST) in children with blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma. 2000;48:902–906.

26 Soundappan SV, Holland AJ, Cass DT, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of surgeon-performed focused abdominal sonography (FAST) in blunt paediatric trauma. Injury. 2005;36:970–975.

27 Suthers SE, Albrecht R, Foley D. Surgeon-directed ultrasound for trauma is a predictor of intra-abdominal injury in children. Am Surg. 2004;70:164–167.

28 Tas F, Ceran C, Atalar MH, et al. The efficacy of ultrasonography in hemodynamically stable children with blunt abdominal trauma: a prospective comparison with computed tomography. Eur J Radiol. 2004;51:91–96.

29 Partrick DA, Bensard DD, Moore EE. Ultrasound is an effective triage tool to evaluate blunt abdominal trauma in the pediatric population. J Trauma. 1998;45:57–63.

30 Shankar KR, Lloyd DA, Kitteringham L, et al. Oral contrast with computed tomography in the evaluation of blunt abdominal trauma in children. Br J Surg. 1999;86:1073–1077.

31 Neish AS, Taylor GA, Lund DP, et al. Effect of CT information on the diagnosis and management of acute abdominal injury in children. Radiology. 1998;206:327–331.

32 Graham JS, Wong AL. A review of computed tomography in the diagnosis of intestinal and mesenteric injury in pediatric blunt abdominal trauma. J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31:754–756.

33 Brenner DJ, Elliston CD, Hall EJ, et al. Estimated risk of radiation-induced fatal cancer from pediatric CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:297–301.

34 Campbell DJ, Sprouse LR, 2nd., Smith LA, et al. Injuries in pediatric patients with seatbelt contusions. Am Surg. 2003;69:1095–1099.

35 Sokolove PE, Kuppermann N, Holmes JF. Association between the “seat belt sign” and intra-abdominal injury in children with blunt torso trauma. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:808–813.